Berwind, Colorado

Berwind | |

|---|---|

Mining ghost town | |

Row of houses in Berwind | |

| Coordinates: 37°18′30″N 104°37′06″W / 37.3084°N 104.6183°W | |

| Country | United States |

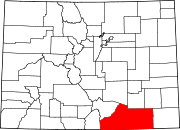

| State | Colorado |

| County | Las Animas |

| Established | 1888 |

| Elevation | 6,542 ft (1,994 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 0 |

| Time zone | UTC-7 (Mountain (MST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-6 (MDT) |

| ZIP codes | 81082[1] |

| GNIS feature ID | 194570[2] |

Berwind is a ghost town in Las Animas County, Colorado, nestled in Berwind Canyon 3.1 miles (5.0 km) southwest of Ludlow and 15 miles (24 km) northwest of Trinidad. The settlement was founded in 1888 as a company town for the Colorado Coal & Iron Company and, from 1892, was operated by the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company. It was a battle site in October 1913 and April 1914 during the Colorado Coalfield War, housing a Colorado National Guard encampment during the latter stages of the conflict.[3]: 118

Description[edit]

Name[edit]

Founded as a coal mining company town in 1888 for the Colorado Coal & Iron Company, the settlement was named for then-company president Edward J. Berwind.[4][5] Berwind was also the founder of the Berwind-White Coal Mining Company. Berwind, West Virginia – another one-time Berwind-owned company town – is also named for him.[6] Later company towns were often simply named for the order in which they were founded, as was the case with CF&I's Primero and Segundo towns.

Location[edit]

The site is located in the Berwind Canyon and is composed of several ruined structures. A neck of the Colorado and Southern railroad ran to the town, connecting it with nearby Ludlow and the coking furnaces in Tabasco.[5] A row of structures along what used to be the main road are still visible and largely intact, as is the old jail.[7]

The proximity of other mines and settlements makes it difficult to delineate the boundaries of Berwind and Tabasco. During their operation, the communities shared amenities, including a schoolhouse named the Corwin School that once served 65 students at a time.[8][9]: 26

History[edit]

Founding[edit]

Berwind was among many company towns established in the Berwind Canyon area in the last two decades of the 1800s. Others include Aguilar and Tabasco. After the merger of the Colorado Coal & Iron Company with the Colorado Fuel Company under Henry S. Grove, the town was assimilated into the new Colorado Fuel & Iron Company. The town was first connected to nearby communities in by the Road Canyon Railway in 1889, a route that became part of the Union Pacific, Denver and Gulf Railway in 1891, and in March 1892 a post office opened.[10]

By 1903, CF&I was the largest coal producer in the Rocky Mountain region.[11]: 14 That same year, partial ownership of the company and its assets–including Berwind–were transferred from John C. Osgood to John D. Rockefeller, who would later gift his portion of CF&I to his son John D. Rockefeller Jr.[9]: 78 Roughly 67 percent of the coal mined at Berwind was taken to the CF&I steel mill in Pueblo, the Minnequa Steel Works.[5]

The mine at Berwind, also known first as El Moro No. 2 and later as CF&I No. 3, would operate from 1890 to 1928, when the town closed.[note a] During those years, CF&I reported the mine had produced 9,076,980 tons of coal.[5][10] In 1912, the combined total of the Berwind and Tabasco mines and their 300 miners was 362,939 tons of coal, with miners receiving roughly $600 per annum.[9]: 26 The first miners at Berwind were Welsh and English men who introduced their methods and unionization under the Knights of Labor, though such organizing was prohibited. The miners following the 1903 Colorado Labor Wars were predominantly immigrants from Eastern Europe, with Greeks, Italians, Poles, Germans, Austrians, Cretans, and Slavs coming to coalfields in Berwind Canyon and across Colorado and Utah.[12]

Colorado Coalfield War and Ludlow Massacre[edit]

Mining conditions in the southern Colorado coalfields proved extremely hazardous during the decade preceding the 1913-14 Colorado Coalfield War, with fatalities twice the national average.[13]: 147 In 1910, two explosions at CF&I mines, first in Primero then Starkville, killed 131.[14][15][16] Between 1894 and 1913, at least 50 miners were killed at the mines in and around Berwind.[17]

Supported by the national organization and Mother Jones, CF&I coal miners in southern Colorado established a local United Mine Workers of American (UMWA) chapter and declared a strike on 23 September 1913.[13]: 238–239 Shortly thereafter, many miners were evicted from the company towns. These evicted miners and their families constructed tent colonies, the largest of which was found outside Ludlow near Berwind.[18] Violence between the strikers and CF&I–with its support from mine guards, detectives, local police, and the Colorado National Guard–began before the end of September and escalated into October.[19]

On 24 October 1913, following a mass deputization in Walsenburg to bolster their numbers against the strikers, a group of about 20 deputies and other militia led by Karl Linderfelt went to guard a section house in Ludlow only to come under fire from Berwind Canyon. From the militia, a National Guardsman named Joe Nimmo was shot and killed.[9]: 127 The militia chased the strikers into Berwind only to become pinned down by rifle fire. A relief unit of 40 militia and Baldwin-Felts detectives armed with a machine gun succeeded in rescuing the remaining militia as a snowstorm rolled in.[7]

As the winter intensified, violence became less frequent and the majority of the National Guard withdrew north to Colorado Springs and Denver, leaving only some militia and guardsmen behind in a series of encampments, including one led by Linderfelt at Berwind, another led by Patrick Hamrock at Ludlow, and a third more distantly at Cedar Hill.[9]: 216

On 20 April 1914, the day after the celebrations of Eastern Orthodox Easter, fighting began between strikers and the militia encamped at Ludlow. A planned signal explosion notified Linderfelt and his men to move from Berwind to the fighting.[9]: 216 The battle, known as the Ludlow Massacre, saw a half-dozen armed and unarmed strikers killed. Three children and eleven women were also killed, most by a fire that burnt the entire tent colony. One National Guard soldier was killed.[13]: 221

Strikers, with public support from elsewhere in the state and material support from the union, initiated a ten-day campaign of disorganized violence against CF&I and other mining interests along a 225-mile front running from the southern border of the state to Louisville. Much of the fighting was within Berwind Canyon, with one mine guard killed at Tabasco and another at nearby the Southwestern Mine Co. mine of Empire. At Empire, strikers laid a 21-hour siege against trapped company-aligned mineworker families that was only broken by the negotiations of a minister and the mayor from Aguilar, also in the Berwind area.[20] The fighting ended on 29 April 1914 after President Woodrow Wilson ordered federal U.S. Army troops into the strike area to break up the fighting.[21]: 208

Final years[edit]

Berwind continued to produce coal for CF&I through to the end of the company's shipments on the Berwind Canyon route of the C&S railroad in 1928. After the strike, the population of the town doubled, with some living in the town through at least 1931.[22] In response to the 1913-14 strike and preceding unionization efforts, future Prime Minister of Canada Mackenzie King recommended a system of improvements to the company towns that included improved pay, some worker representation, and added amenities such as YMCAs and other leisure.[23][24] This new system, called the "Rockefeller Plan," led company towns like Berwind to gain the favor of miners over independent outfits from 1915 onward.[12] CF&I's total investment into Berwind was estimated at $362,765 in 1922. Estimates of Berwind's population at its height suggest the community exceeded 1,000 people.[25] Berwind's population was 294 in 1902,[26] and was 550 in 1925.[27]

In 1927, the mines were manned by 290 miners and still primarily mined by hand rather than by machine.[5] In total, at least 75 miners suffered mining-related deaths in Berwind's mines while they were operated by CF&I, not including those killed in Tabasco or other nearby operations.[17]

Archaeology[edit]

In the 1990s, the University of Denver began a series of surveys and excavations at both Berwind and Ludlow as part of a wider historical investigation known as the Colorado Coal Field War Project. Besides the archaeology at both sites, oral interviews with former residents and document research were utilized.[22]

See also[edit]

- Bibliography of Colorado

- Geography of Colorado

- History of Colorado

- Index of Colorado-related articles

- List of Colorado-related lists

- Outline of Colorado

- George McGovern, 1972 Democrat nominee for U.S. president who published a history of the Colorado Coalfield War

- Ivy Lee, public relations pioneer who helped Rockefeller following the Ludlow Massacre

Notes[edit]

- ^ a. The mine's name, El Moro No. 2, is in reference to the CF&I operation at El Moro elsewhere in the county.

References[edit]

- ^ "Berwind Ruins, Las Animas County, Colorado". CO HomeTownLocator. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ "Berwind Ruins". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. October 13, 1978. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ Martelle, Scott (2007). Blood Passion: The Ludlow Massacre and Class War in the American West. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-4419-9.

- ^ "Text for the Berwind Historical Marker". Archaeology of the Colorado Coal Field War, 1913-1914. University of Denver. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Schreck, Christopher J. (2018). "Berwind Coal Mine (El Moro No. 2)". Colorado Fuel and Iron: Company Mines. Columbia, SC: Alliance for Networking Visual Culture, University of South Carolina. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ DellaMea, Chris. "Berwind, WV". Coalfields of the Appalachian Mountains. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ a b Hart, Steve; Osterhout, Shannon (2014). "Coal and Coking Camps - Starkville, Cokedale, Boncarbo, Berwind Canyon, Hastings, and Ludlow". 2014 Mining History Association Tour. Boise, ID: Mining History Association. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ "Berwind - Tabasco school". Welborn Collection. Denver Public Library. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f McGovern, George Stanley; Guttridge, Leonard F. (1972). The Great Coalfield War. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0395136490. OCLC 354406.

- ^ a b "Thirty Italians and 500 goats". World Journal. Aguilar, CO. 2015. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- ^ Scamehorn, H. Lee (1992). "1: The Colorado Fuel and Iron Company, 1892-1903". Mill and Mine: The CF&I in the Twentieth Century. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0803242142.

- ^ a b Margolis, Eric (2000). "Life is Life: A Mining Family in The West". Arizona State University. Archived from the original on February 20, 2020. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ a b c Andrews, Thomas G. (2010). Killing for Coal. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-73668-9. OCLC 1020392525. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ Hellmann, Paul T. (February 14, 2006). Historical Gazetteer of the United States. Routledge. p. 143. ISBN 1-135-94859-3.

- ^ Mitchell, Karen. "Primero Mine". Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ "1910 Explosion at the Starkville Mine Killed 56 Men". The Denver Post. Denver. August 24, 2012. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ^ a b Sherard, Gerald E. (2006). "Pre-1963 Colorado Mining Disaster". Lakewood, CO. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ DeStefanis, Anthony Roland (2004). "Guarding capital: Soldier strikebreakers on the long road to the Ludlow massacre". Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. The College of William & Mary. doi:10.21220/s2-d7pf-f181. S2CID 198026553.

- ^ West, George P. (1915). Report on the Colorado Strike (Report). United States Commission on Industrial Relations.

- ^ "30 Besieged in Mine May Be Suffocated; Mouth of Slope Blocked by Dynamite Explosions Caused by Strikers". The New York Times. New York City. April 23, 1914. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ Laurie; Cole (1997). The Role of Federal Military Forces in Domestic Disorders, 1877–1945. Washington: Center of Military History, United States Army.

- ^ a b "Archaeology at Berwind". Colorado Coal Field War Project. University of Denver. 2003. Archived from the original on December 21, 2020. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

- ^ Hennen, John (2011). "Reviewed Work: Representation and Rebellion: The Rockefeller Plan at the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company, 1914-1942 by Jonathan H. Rees". The Journal of American History. 97 (4): 1149–1150. doi:10.1093/jahist/jaq129. JSTOR 41508986.

- ^ Chernow, Ron (1998). Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller Sr. Random House. pp. –571–586. ISBN 0-6794-3808-4.

- ^ "Needlecraft Magazine ; Sewing magazine from Giovanna "Jenny" DeLauro's hope chest". History Colorado Online Collection. History Colorado. March 20, 2020. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- ^ Cram's Modern Atlas: The New Unrivaled New Census Edition. J. R. Gray & Company. 1902. p. 248.

- ^ Premier Atlas of the World: Containing Maps of All Countries of the World, with the Most Recent Boundary Decisions, and Maps of All the States, Territories, and Possessions of the United States with Population Figures from the Latest Official Census Reports, Also Data of Interest Concerning International and Domestic Political Questions. Rand McNally & Company. 1925. p. 173.