Allendale Plantation

Allendale Plantation | |

Allendale Plantation (2012) | |

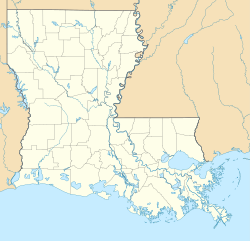

| Location | Port Allen, Louisiana, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 30°29′45″N 91°16′24″W / 30.49583°N 91.27333°W |

| Area | 13 acres (5.3 ha) |

| Built | c. 1855 |

| NRHP reference No. | 96001263[1] |

| Added to NRHP | November 1, 1996 |

Allendale Plantation, also known as the Allendale Plantation Historic District, is a historic site and complex of buildings that was once a former sugar plantation founded c. 1855 and worked by enslaved African Americans (prior to the end of the American Civil War). It is located in Port Allen, West Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana.[2]

The site has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places since November 1, 1996, it is noted for its agricultural significance as an example of a reconstruction era sugar plantation system in southern Louisiana.[3]

History[edit]

In February 1852, Henry Watkins Allen and William Nolan purchased the Westover Plantation.[3][4] Henry Watkins Allen had served as a brigadier general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War, as well as serving as the 17th Governor of Louisiana.[5][6] Three years later in 1855, the land was divided and split; with Nolan keeping the name Westover Plantation on his portion of land and Allen using the name Allendale for his portion of the property.[3]

Henry Watkins Allen (1855–1865)[edit]

The Allendale Plantation under Henry Watkins Allen grew to 2,027 acres (820 ha), with 627 acres (254 ha) farmed.[7] Allen owned 125 enslaved African Americans.[8][9] Allen built his own railroad, which had been headquartered in what is now the town of Port Allen.[8]

During the American Civil War (1861–1865), parts of the Allendale Plantation had burned, including the Allendale Mill.[10][11] Allen had moved to Mexico art the war in 1865, and a year later he died on April 22, 1866, in Mexico City,[12] and as a result the Allendale Plantation held many owners after his death.[3]

Kahao family (starting in 1882)[edit]

In 1882, the plantation was purchased by brothers John Kahao and Martin James Kahao, formerly from Kansas.[3] The Kahao family bought up smaller neighboring plots of land, in order to grow the total land size.[3] The Allendale Plantation records showed that after 1908, many of the laborers were still being paid in tokens and merchandise checks instead of cash, which went against Federal law changes.[13] The Kahao family operated it as a sugar mill into the 1930s.[3]

Architecture[edit]

The Allendale Plantation Historic District is the name used by the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP), and it includes 15 wood-framed structures that were once part of the Allendale Plantation.[3] Some 13 of the 15 structures were former residences on the property, as well as a church and an office building.[3] The plantation manor house and the sugar mill have long since been destroyed.[3] In January 1887, the nearby Westover Plantation's main residence had a fire and burned down by accident, when they were trying to use fire to clear nearby weeds.[14][15]

Multiple cabins built between 1870 and 1900 are found on the site, they were once used by sharecropping laborers.[3] The cabins were generally built as four-rooms that were occupied by a single family.[3] The West Baton Rouge Museum has had one of the Allendale Plantation slave cabins onsite since 1976 (once owned by Allen, pre-1865) and the museum offers a narrative history.[16][9] In 2016 and 2020, the West Baton Rouge Museum narrative tour featuring Allendale Plantation been criticized for being biased and narrow in scope.[16][9]

The Allendale Church was built for laborers, and the office on the property held all of the related operations paperwork.[3] Most of the plantation buildings were moved often, due to flooding of the area.[3]

As of 1996, there were only six remaining examples of the sugar plantation complexes and systems in southern Louisiana.[3]

See also[edit]

- List of plantations in Louisiana

- Plantation complexes in the Southern United States

- Statue of Henry Watkins Allen

- National Register of Historic Places listings in West Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana

References[edit]

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. November 2, 2013.

- ^ "NPGallery Asset Detail, Allendale Plantation Historic District". NPGallery Digital Asset Management System, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2021-05-27.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Louisiana Department of Historic Preservation National Register (August 1987). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Allendale Plantation Historic District". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved May 27, 2021. (with with 13 accompanying photos taken in August 1996)

- ^ "Saturday". Newspapers.com. Sugar Planter. 23 March 1867. p. 5. Retrieved 2021-05-28.

- ^ Dorsey, Sarah A. (1866). Recollections of Henry Watkins Allen. New York City, NY: M. Doolady.

- ^ "Memorial to Gov. Henry W. Allen". Newspapers.com. The Shreveport Journal. 3 June 1969. p. 6. Retrieved 2021-05-27.

- ^ Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Louisiana: Embracing an Authentic and Comprehensive Account of the Chief Events in the History of the State, a Special Sketch of Every Parish and a Record of the Lives of Many of the Most Worthy and Illustrious Families and Individuals. Claitor's Pub. Division. 1975. p. 504.

- ^ a b "Louisiana's Warrior Governor". Abbeville Institute. Retrieved 2021-05-28.

- ^ a b c Miller, Robin (July 18, 2020). "Confederate Statue Becomes Point of Controversy in Louisiana". U.S. News & World Report. Associated Press, The Advocate.

- ^ Louisiana: A Guide to the State. United States Works Progress Administration (Louisiana). US History Publishers. 1943. p. 452. ISBN 978-1-60354-017-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Leeper, Clare D'Artois (1976). Louisiana Places: A Collection of the Columns from the Baton Rouge Sunday Advocate, 1960-1974. Legacy Publishing Company.

- ^ Guterl, Matthew Pratt (2011). "Refugee Planters: Henry Watkins Allen and the Hemispheric South". American Literary History. 23 (4): 724–750. doi:10.1093/alh/ajr039. ISSN 0896-7148. JSTOR 41329612.

- ^ Lurvink, Karin (2018-01-03). Beyond Racism and Poverty: The Truck System on Louisiana Plantations and Dutch Peateries, 1865-1920. Brill. p. 191. ISBN 978-90-04-35181-3.

- ^ "Baton Rouge Notes". Newspapers.com. The Times-Democrat. 21 Jan 1887. p. 4. Retrieved 2021-05-27.

- ^ "Port Allen News". Newspapers.com. The Times-Picayune. 21 January 1887. p. 1. Retrieved 2021-05-28.

- ^ a b Rose, Julia (2016-05-02). Interpreting Difficult History at Museums and Historic Sites. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-7591-2438-7.

Further reading[edit]

- Morgan Dawson, Sarah (1913). A Confederate Girl's Diary. Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 9780557358915. - The A Confederate Girl's Diary (1913) book has accounts of seeing the explosion of the CSS Arkansas from the Westover Plantation, during the America Civil War.

- 1855 establishments in Louisiana

- Sugar plantations in Louisiana

- National Register of Historic Places in West Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana

- Relocated buildings and structures in Louisiana

- Residential buildings on the National Register of Historic Places in Louisiana

- Slave cabins and quarters in the United States

- Houses in West Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana

- Historic districts on the National Register of Historic Places in Louisiana