Alexander William Doniphan

Alexander Doniphan | |

|---|---|

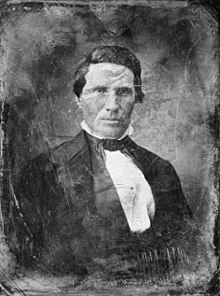

Alexander William Doniphan (Mathew Brady's studio) (Library of Congress collection) | |

| Born | July 9, 1808 Mason County, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Died | August 8, 1887 (aged 79) Richmond, Missouri, U.S. |

| Resting place | Fairview Cemetery Liberty, Missouri, U.S. 39°14′34″N 94°25′26″W / 39.2428°N 94.4239°W |

| Alma mater | Augusta College |

| Occupation(s) | Lawyer, soldier |

| Known for | Sparing Joseph Smith's life Author Kearny code |

| Height | 6 ft 4 in (1.93 m) |

| Title | Colonel |

| Spouse |

Elizabeth Jane Thornton

(m. 1838–1873) |

| Children | John Thornton Alexander William Jr. |

| Parent(s) | Joseph and Anne Fowke (née Smith) Doniphan |

| Military career | |

| Nickname(s) | "The American Xenophon"[1] |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1836–1848 |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Unit | 1st Missouri Mounted Volunteers |

| Battles / wars | |

| Signature | |

Alexander William Doniphan (July 9, 1808 – August 8, 1887[2]) was a 19th-century American attorney, soldier and politician from Missouri who is best known today as the man who prevented the summary execution of Joseph Smith, founder of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, at the close of the 1838 Mormon War in that state. He also achieved renown as a leader of American troops during the Mexican–American War, as the author of a legal code that still forms the basis of New Mexico's Bill of Rights, and as a successful defense attorney in the Missouri towns of Liberty, Richmond and Independence.

Early life

[edit]Doniphan was born near the town of Maysville, Kentucky, near the Ohio River.[3] He was the youngest of the ten children of Joseph and Anne Fowke (née Smith) Doniphan, both natives of Virginia. Joseph had been a friend of Daniel Boone, and both of Alexander's grandfathers had fought in the American Revolution.[4]

Doniphan graduated from Augusta College in 1824, and was admitted to the bar in 1830. He began his law practice in Lexington, Missouri, but soon moved to Liberty, where he was a successful lawyer. Doniphan always served as a defense attorney, never as a prosecutor, and was noted for his oratorical skills. He served in the state legislature in 1836, 1840, and 1854, representing the Whig Party.[4]

The Heatherly War

[edit]Doniphan's friend and partner, David Rice Atchison, was a member of the Liberty Blues, a volunteer militia company. In June 1836 he persuaded Doniphan to join them. Doniphan took part in the so-called Heatherly War as an aide to Colonel Samuel C. Allen. As the Liberty Blues moved toward the Missouri border, Stephen Watts Kearny, then a lieutenant colonel, joined them from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.[5]

Kearny discovered that the Heatherly brothers had sold whiskey to a hunting party of Potawatomi Indians, then stole their horses. The Potawatomis pursued the brothers and killed three of them. The brothers' mother sought revenge by claiming that the Potawatomis had gone on the war path, while the remaining Heatherly brothers robbed and murdered two white men, trying to place the blame on the Potawatomis. The "war" ended with the Heatherly family being arrested, tried, and convicted.[5]

The 1838 Mormon War

[edit]Starting in 1831, Jackson County, Missouri, had become home to several members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints,[6] a religious organization founded by Joseph Smith in upstate New York a year earlier. By 1833, approximately 1200 Mormons lived in Jackson County, where they aroused the ire of many earlier settlers by their belief that American Indians, whom they called "Lamanites", were the descendants of ancient Israelites who had migrated to the New World centuries earlier (see Book of Mormon). Other fundamental differences between Mormons and non-Mormons exacerbated the situation, especially a belief that the Mormons were abolitionists, who planned to foment uprisings among Missouri slaves[citation needed]. Denunciations of abolitionism in the church press did nothing to allay their neighbors' fears, and matters came to a head in late 1833, when the Mormons were forcibly expelled from the county.

Following these events, Joseph Smith and other church leaders petitioned the governor of Missouri for protection, but were largely ignored. This led them to hire Doniphan and Atchison, among others, to defend their rights in court.[7] Doniphan assisted in the creation of a special county in northwestern Missouri for the Mormons, but continued friction between Mormons and non-Mormon settlers in that region ultimately led to the outbreak of the 1838 Mormon War. Following a clash between Mormons and state militia at the Battle of Crooked River, governor Lilburn Boggs issued his infamous "Extermination Order", directing that the Mormons be "exterminated, or driven from the state".

As a brigadier general in the Missouri Militia, Doniphan was ordered into the field with other forces to operate against the Mormons, even though he had worked diligently to avoid the conflict, and believed that the Mormons were largely acting in self-defense. After the surrender of Far West, General Samuel Lucas took custody of Joseph Smith and other Mormon leaders, and instituted a drumhead court martial (kangaroo court), which declared Smith and the others guilty of treason, and ordered Doniphan to execute them. Doniphan indignantly refused, saying: "It is cold blooded murder. I will not obey your order. ... [I]f you execute these men, I will hold you responsible before an earthly tribunal, so help me God".[8] The Mormon leaders were accordingly sent to Liberty Jail during the winter, to await trial during the following spring of 1839, at which trial Doniphan was appointed as their defense attorney and energetically defended them at the risk of his good reputation and, in all probability, his life. Ultimately, the church leaders were permitted to escape from custody, and they subsequently made their way to the new Mormon settlement in Hancock County, Illinois, where Joseph Smith was killed in 1844. In Doniphan's honor, Joseph and Emma Hale Smith named a son Alexander Hale Smith.[9]

In 1843, Porter Rockwell, a controversial Mormon figure later known as "the destroying angel of Mormondom", was arrested in St. Louis and accused of carrying out a failed assassination attempt on (now former) governor Boggs. After nine months of being imprisoned in poor conditions, he was able to hire Doniphan to defend him; Doniphan managed to have the main charge of attempted murder dismissed for lack of evidence, and arranged for Rockwell to serve a five-minute sentence (for a jailbreak attempt during his imprisonment) in the county jail before being released. Rockwell made his way to Illinois, then later to Utah, where he achieved fame as a lawman and Wild West figure.[10][11]

Forty years after the events of 1838, an aged Doniphan visited Salt Lake City, Utah Territory, which had become the nucleus for the largest body of Mormons following the death of Joseph Smith. He received a hero's welcome, and was feted and thanked by the Latter-day Saints for his role in saving the life of their prophet.[12]

Mexican–American War

[edit]In 1846, at the beginning of the Mexican–American War Doniphan was commissioned as Colonel of the 1st Regiment of Missouri Mounted Volunteers, and served in several campaigns, including General Stephen W. Kearny's capture of Santa Fe and an invasion of northern Mexico (present day northern New Mexico).

After Santa Fe was secure, Kearny left Doniphan in charge in New Mexico, and departed towards California on September 25, 1846.[13] Doniphan's orders were to wait until General Sterling Price arrived with the Second Missouri Mounted Volunteers, who were coming from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas; after they arrived he was to lead them to Chihuahua via Ciudad Juarez, then known as Paso del Norte. They were to link up with Brigadier General John E. Wool, who was moving southwest from San Antonio, Texas toward Guerrero and Monclova, Coahuila, to attack Monterrey, Nuevo León from the west. Kearny had known that the Navajo people were going on the war path. With the Spanish gone, the Navajos wanted to test these new American soldiers; hence, as Doniphan waited for Price, the Navajos mounted a raid and kidnapped 20 Mexican families.[14][15]

Doniphan was eager to start south, but he first had to wait for Price to arrive. Kearny, and then Doniphan had tried to negotiate with the Navajos, together with the Ute tribe and Apaches, but had made little progress. After Price arrived with his force, Kearny, near the present-day border of Arizona and New Mexico, learned that the Navajos had attacked some sheepherders, killed them, and stolen their herd of 2,000 sheep. Kearny dispatched a message to Doniphan to attack the Navajos on October 2, 1846. Doniphan signed a peace treaty with the Utes, and then took three companies and headed west (toward present day Gallup) in pursuit of the Navajos.[15][16]

Doniphan was unable to find his foe, but they sent a member of their tribe to find him and tell him they wanted to negotiate. At first, Kearny was willing to be amicable with the Navajos, but the following day, October 3, the Navajos attacked the village of Polvadera, stealing the livestock and sending the residents fleeing for their lives. Kearny now called for all citizens of the territory to take up arms and aid the cavalry in finding the Navajos, retrieving the stolen property, and to "make reprisals and obtain redress for the many insults they received from them".[17] Returning to their campaign against the Mexican Army, Doniphan's men won the Battle of El Brazito (outside modern day El Paso, Texas) and then won the Battle of the Sacramento River, enabling the capture of the city of Chihuahua. At the latter battle, Doniphan and his force were outnumbered by more than four to one in troops, and nearly two to one in artillery, but only lost one dead and eleven wounded to the Mexican loss of 320 dead, 560 wounded and 72 prisoners.[18]

Doniphan's men ultimately embarked on ships and returned to Missouri via New Orleans to a hero's welcome. His campaign had taken him and his men on a march of nearly 5,500 miles (8,900 km), considered the longest military campaign since the times of Alexander the Great.

Return to civilian life

[edit]After the Mexican–American War, Doniphan was appointed by General Kearny to write a code of civil laws (known as the "Kearny code") in both English and Spanish. It was to be used in the lands annexed from Mexico, and still forms the basis of New Mexico's Bill of Rights and legal code. He was also instrumental in the establishment of William Jewell College in his home town of Liberty; one of his colleagues on the college's board of trustees was Rev. Robert James, father of Frank and Jesse James. Doniphan also served as the first Clay County superintendent of schools.

Doniphan was a moderate in the events leading up to the American Civil War, opposing secession and favoring neutrality for Missouri. Although a slaveholder, Doniphan advocated the gradual elimination of slavery. This was in response to proposals of the Republican Party to make emancipation immediate, without compensation to the slaveowners or any preparation of the slaves for life as free men.

Doniphan attended a peace conference at Washington, D.C., in February 1861, but returned home frustrated at its inability to solve the crisis. He was appointed Brigadier General and commander of the Fifth Division of the Missouri State Guard, but declined.[19] Doniphan was also offered high rank in the Union Army, but refused to fight against the South. In 1863 he moved to St. Louis and remained there for the rest of the war. During a meeting with Doniphan, President Abraham Lincoln is alleged to have remarked: "Doniphan, you are the only man I've ever met whose appearance came up to my expectations".[18] During the war, Doniphan worked in St. Louis with the Missouri Claims Commission, handling pension applications.

In the late 1860s, Doniphan re-opened his law office in Richmond, Missouri, where he died at the age of 79. He is buried in Fairview Cemetery in Liberty under an obelisk.

Family

[edit]Doniphan married Elizabeth Jane Thornton (December 21, 1820–July 19, 1873)[20][21][22] on December 21, 1837,[21] in Liberty, Missouri. Her father was a colleague of Doniphan's in the state legislature.[21] Their wedding was on her 17th birthday, and it was a double-wedding ceremony, with Elizabeth's sister Caroline and Oliver P. Moss being married at the same time.[21] Elizabeth became sickly in the 1850s, and during the burial of her son John she suffered a stroke, which left her a semi-invalid for the remainder of her life.[23] Elizabeth Doniphan died in New York City of pulmonary hemorrhage.[22]

The couple had two sons, John Thornton (September 18, 1838–May 9, 1853)[23][24] and Alexander William Jr. (September 10, 1840–May 11, 1858),[24][25] neither of whom lived to age 18. John Thornton Doniphan died from accidental poisoning: while visiting his uncle James Baldwin, he sought relief for a toothache in the middle of the night but mistakenly took corrosive sublimate (mercury chloride), thinking that it was Epsom salts.[23][25] Alexander William Doniphan Jr. died while attending Bethany College, in Bethany, West Virginia, when he drowned in a flood-swollen river.[25]

Legacy

[edit]- Doniphan County, Kansas, was created and named for him in 1855. He is also the namesake of the town of Doniphan, Missouri.[26]

- Alexander Doniphan remains highly esteemed by members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints for saving the life of Joseph Smith and other early church leaders. His story is routinely told in church literature and histories.

- Doniphan was inducted into the Hall of Famous Missourians in 2008, and a bronze bust depicting him is on permanent display in the rotunda of the Missouri State Capitol in Jefferson City.

- A large bronze statue of Doniphan stands on the grounds of the Ray County courthouse, in Richmond, Missouri.

- The American Legion Boys State of Missouri named Doniphan City one of their divisions in his honor.

- Doniphan Drive, in El Paso, Texas, is named for Doniphan, from the Battle of El Brazito fought near that city.

- Missouri Highway 152, running between Liberty, Missouri, and Leavenworth, Kansas, is named the "Alexander Doniphan Memorial Highway".

- Camp Doniphan was established during the Army buildup for World War I. It is located next to Fort Sill, just outside Lawton, Oklahoma.

- William Jewell College in Liberty, Missouri, has named its prestigious Senior Award named in honor of Colonel Alexander Doniphan. The Alexander Doniphan Award is presented to the male of the graduating senior class whom demonstrates leadership, strong academics, and is considered by his peers to be the most likely to walk the furthest in life, or "most likely to succeed."

- The Liberty, Missouri School District has named an elementary school in honor of Doniphan.

- Actor Peter Lawford portrayed Doniphan in a 1965 episode of the NBC anthology series, Profiles in Courage, based on an earlier book attributed to John F. Kennedy, who was a brother-in-law of Peter Lawford.[27]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Doniphan's March". A Continent Divided: The U.S.-Mexico War. University of Texas Arlington. Archived from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ BIRTH:

1—Launius, Roger D., (1997). - Alexander William Doniphan: Portrait of a Missouri Moderate. - Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. - p.1.

ISBN 978-0-8262-1132-3.

2—Muench, James F., (2006). - Five Stars: Missouri's Most Famous Generals, - Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. - p.6.

ISBN 978-0-8262-1656-4.

—DEATH:

1—Launius. - p. 279.

2—Muench. - p. 32. - ^ Dawson Joseph G., (1999). - Doniphan's Epic March: The 1st Missouri Volunteers in the Mexican War. - Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. - p. 6. - ISBN 978-0-7006-0956-7.

- ^ a b Historic Liberty: Doniphan Walking Tour Archived 2011-10-09 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Muench. - pp.7-8.

- ^ This organization was called the "Church of Christ" at this time; it later became the "Church of the Latter Day Saints", and then the "Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints" in 1838. Today, multiple groups claim to be the continuation or successor of Smith's original church, the largest of which is The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, in Salt Lake City, Utah; see Latter Day Saint movement and List of sects in the Latter Day Saint movement.

- ^ Muench. - pp. 8–9.

- ^ History of the Church, 3:190–91

- ^ Quinn, D. Michael. "The Mormon Hierarchy Origins of Power." Salt Lake City: Signature Books in association with Smith Research Associates, 1994. pp. 100–101.

- ^ Deseret News, Saturday, August 31, 1935, article "Ancestry of Orrin Porter Rockwell".

- ^ "Chapter 6", History of the Church, vol. 6, pp. 134–142, archived from the original on 2015-01-28, retrieved 2013-07-28

- ^ Missouri Baptist Historical Society Archived 2011-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ New Mexico. Federal Writers' Project, U.S. History Publishers (1953). ISBN 978-1-60354-030-8. p. 72.

- ^ Launius, pp. 116–117.

- ^ a b Muench, p. 21.

- ^ Launius, pp. 118–120.

- ^ Locke, Raymond Friday, (2002). The Book of the Navajo. Los Angeles, California: Mankind Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87687-500-1. p. 208.

- ^ a b P. L. Gray. Gray's Doniphan County History. Bendina, KS: Roycroft Press, 1905, Ch. 2.

- ^ Sterling Price's Lieutenants, p. 217

- ^ Muench. - p.12.

- ^ a b c d Launius. - p.41.

- ^ a b Launius. - p.274.

- ^ a b c Launius. - p.217.

- ^ a b Launius. - p.42.

- ^ a b c Launius. - p.238.

- ^ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. pp. 107.

- ^ "Profiles in Courage: "General Alexander William Doniphan", January 17, 1965". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- Peterson, Richard C.; McGhee, James E.; Lindberg, Kip A.; Daleen, Keith I; Sterling Price's Lieutenants (rev. ed.), Two Trails Publishing, Independence, MO (2007)

External links

[edit]- "Alexander William Doniphan". Find a Grave. Retrieved September 3, 2010.

- Marker to Doniphan in Clay Co., MO. - Missouri "Mormon" Frontier Foundation. - John Whitmer Historical Association.

- Doniphan biography. - Kansas "bogus legislature" website.

- Doniphan. - Columbia Encyclopedia.

- Speaking of History Podcast with audio of John Dillingham speech on the life of Alexander Doniphan. - presented at the Truman Presidential Library in May, 2007.

- [1]. A tour of Alexander Doniphan historical sites in Liberty, Missouri.