1918 Louisiana hurricane

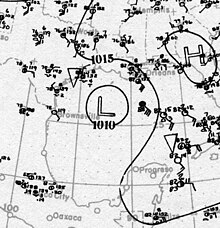

Surface weather analysis of the hurricane over the northwestern Gulf of Mexico on August 6 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | August 1, 1918[a] |

| Dissipated | August 7, 1918 |

| Category 3 major hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 120 mph (195 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 955 mbar (hPa); 28.20 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 34 |

| Damage | $5 million[b] |

| Areas affected | Louisiana, Texas |

Part of the 1918 Atlantic hurricane season | |

The 1918 Louisiana hurricane was a tropical cyclone that struck southwestern Louisiana as a major hurricane in August 1918. The first tropical cyclone of the 1918 Atlantic hurricane season, it was first detected south of Barbados on August 1. Moving west-northwest, the storm traversed the Caribbean Sea and gradually strengthened, though the sparse observations available did not sample the storm's intensity. On August 5, the storm attained hurricane intensity after moving through the Yucatán Channel into the Gulf of Mexico. The hurricane strengthened further into a major hurricane before making landfall near Cameron, Louisiana, on August 6 with maximum sustained winds of around 120 mph (195 km/h). The storm quickly moved north-northwest into Texas and Oklahoma while rapidly weakening, and eventually dissipated on August 7 over eastern Oklahoma.

Due to a lack of observations and the hurricane's small size, the major hurricane struck Louisiana with little advance warning. The hurricane quickly moved through southwestern Louisiana, limiting rainfall accumulations in the storm's path. However, the hurricane produced damaging winds with gusts reaching about 125 mph (201 km/h) in Sulphur and exceeding 100 mph (160 km/h) in Lake Charles. The most severe damage occurred in those areas, with many buildings destroyed. Corn and cotton crops also suffered from the strong winds. Along the coast, buildings in Grand Chenier and Creole were swept by storm surge. The hurricane killed 34 people in Louisiana, and the Weather Bureau estimated the total damage toll to be around $5 million.[b]

Meteorological history[edit]

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

Weather observations first indicated that a tropical disturbance was south of Barbados and moving towards the west-northwest on August 1.[1] The official Atlantic hurricane database[c] lists a tropical storm developing southeast of Barbados by 00:00 UTC on August 1[a] with maximum sustained winds of 40 mph (65 km/h).[4] However, there were no accompanying measurements of gale-force winds, and it is unclear whether the storm exhibited a well-defined wind circulation as it moved through the Lesser Antilles into the Caribbean Sea on August 1–2.[5] No land stations or ships observed the center of the storm as it traversed the Caribbean. The tropical cyclone passed south of Jamaica on August 3 and moved through the Yucatán Channel into the Gulf of Mexico on August 5.[1][4] Maritime observations suggested that the storm intensified into a hurricane by 12:00 UTC on August 5 north of the Yucatán Peninsula.[5]

The United States Weather Bureau did not receive any reports regarding the between the afternoon of August 4 and the morning of August 6, by which time air pressures had already begun to fall along the U.S. Gulf Coast.[1] A 2008 reanalysis of the storm conducted by the Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory estimated that the hurricane reached the equivalent of Category 3 intensity on the modern Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale by 06:00 UTC on August 6, making it a major hurricane.[d][5][4] At around 17:30 UTC that day, the hurricane made landfall 30 mi (48 km) east of the Sabine River near Cameron, Louisiana, with maximum sustained winds of approximately 120 mph (195 km/h). A minimum air pressure of 960 mbar (hPa; 28.35 inHg) was observed in Sulphur, Louisiana, implying that the hurricane had a minimum central pressure of about 955 mbar (hPa; 28.20 inHg). The hurricane was slightly smaller than average at landfall, with a radius of maximum winds extending 17 mi (27 km) from its center.[5] The storm continued to the north-northwest after landfall with a forward speed of around 18 mph (29 km/h),[1][5] crossing the Sabine River into Texas south of Merryville, Louisiana,[7] and moving along the state border between Louisiana and Texas as it rapidly weakened. The 2008 reanalysis determined that the storm dissipated over eastern Oklahoma after 18:00 UTC on August 7.[5]

Impact[edit]

The hurricane's small size shortened the period of inclement weather heralding the impending hurricane, providing little warning of the storm. A Weather Bureau forecast published on the morning of August 6 remarked that "A tropical disturbance is evidently approaching the Gulf coast," but that the point of landfall could not be determined.[8] Hurricane warnings were ultimately issued by the Weather Bureau for the Louisiana coast and the Texas coast east of Galveston during the afternoon just prior to landfall, though the agency also provided antecedent notices of a tropical storm in the area. The swath of significant damage resulting from the small hurricane spanned 25 mi (40 km) across,[1] with impacts felt between Orange, Texas, and Jennings, Louisiana.[9] Minor to negligible damage occurred along the hurricane's periphery. The center of the hurricane moved through Cameron, Calcasieu, and Beauregard parishes in Louisiana,[1] and the most destructive impacts of high winds sustained in Cameron and Calcasieu parishes.[7] The hurricane killed 34 people in Louisiana and injured at least 68. The Weather Bureau estimated that total property and crop damage amounted to around $5 million, but this figure excluded the damage in smaller villages and lost livestock.[1] The heaviest property damage occurred at Gerstner Field, Lake Charles, Louisiana, Lockmoor, and Sulphur. Fires indirectly caused by the hurricane caused limited additional damage. Strong winds also wrought significant damage to cotton and corn crops in extreme southwestern Louisiana.[7] The rice crop sustained comparatively less severe losses due to their recent planting.[1] The storm surge produced by the hurricane raised tides at Morgan City 3 ft (0.91 m) above normal and Johnson Bayou 2.4 ft (0.73 m) above normal. Higher surge heights likely occurred but were unmeasured over eastern Cameron Parish.[1]

The hurricane's quick passage of Louisiana led to relatively low rainfall accumulations despite the moderate to heavy rainfall ahead of the storm and on its eastern flanks.[10] Rainfall amounts generally ranged between 2–3 in (51–76 mm) along the Louisiana coast over a 24-hour period,[10] with 2–4 in (51–102 mm) rainfall totals over southwestern and south-central Louisiana.[7] A peak rainfall total of 4.91 in (125 mm) was measured near Franklin,[11] and only one weather station recorded over 4 in (100 mm) of rain in a 24-hour period.[10] Rain from the hurricane also extended into Texas along the state border with Louisiana.[12]

The storm surge razed homes in Grand Chenier and Creole.[9] The mail and passenger Borealis Rex departed from Cameron en route to Lake Charles early on August 6 when it encountered the hurricane. Strong winds pushed the vessel into the shoreline as it entered Prien Lake, whereupon the passengers sought refuge in a nearby home. As winds switched from the north, the boat was pushed a mile downstream and capsized in 8–10 ft (2–3 m) waves. All passengers survived the hurricane.[1][9] At Garstner Field, 7 hangars and 96 airplanes were destroyed. Three pilots were killed.[9] An anemometer in Lake Charles recorded a maximum five-minute sustained wind of 80 mph (130 km/h) with gusts estimated to be in excess of 100 mph (160 km/h);[1][9] the instrument was disabled by either debris or the strong wind after measuring the maximum wind speed.[1] A string of freight cars in Lake Charles were blown into the rear of a train, smashing the vehicles and killing 25 people.[13] The Temple Sinai was severely damaged while the old Presbyterian church was demolished. A portion of the Methodist Episcopal Church was detached and disintegrated. The Goosport milling district was ravaged by a combination of strong winds and fire, with a red glow in the sky visible 25 mi (40 km) away in DeQuincy.[9] In DeQuincy, at least 50 residences were destroyed while several churches and stores were rendered useless. Three people were killed in the city, and another three deaths occurred at Hammond Camp to its east.[14] Westlake was described as "a scene of desolation" with a majority of its buildings leveled.[9]

Wind gusts as high as 125 mph (201 km/h) were reported in Sulphur.[9] Automobiles in Sulphur were stripped of their tops and laid on their bodies. Many buildings were unroofed or otherwise pushed off their foundations.[15] Few businesses remained standing, with The Union Sulphur Mines suffering most severely.[9] A large warehouse was blown across a set of railroad track in Vinton.[15] Oil fields adjacent to Vinton and Edgerly sustained what was described as "great damage," and rice crops across Calcasieu and Jefferson Davis parishes saw their stalks broken or bent.[16] In Lafayette, Louisiana, travel came to a standstill as wreckage from homes and toppled communication lines littered roadways. The Pierce Oil Corporation Building collapsed upon a number of occupants, resulting in minor injuries. Several other structures caught fire as they collapsed upon hot stoves, though heavy rainfall inflicted by the hurricane helped to quell the resultant flames. Losses from the city topped $1 million.[17]

In the aftermath of the storm, soldiers patrolled the debris-littered streets in an effort to combat looting and civil unrest.[18] The Big Lake Gunnery School, one of the only buildings at Gerstner Field intact in the storm's wake, was used as a base for relief work.[9]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b All times and dates are based on Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) unless otherwise noted.

- ^ a b All monetary values are in 1910 United States dollar unless otherwise noted.

- ^ HURricane DATa (HURDAT) is the official track database for tropical cyclones in the North Atlantic Ocean and contains information on the positions and intensities of storms dating back to 1851.[2][3]

- ^ A major hurricane is a storm that ranks as Category 3 or higher on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale.[6]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Henry, Alfred J. (August 1918). "Forecasts and Warnings for August, 1918". Monthly Weather Review. 46 (8). American Meteorological Society: 378–380. Bibcode:1918MWRv...46..378H. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1918)46<378:FAWFA>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ "Tropical Cyclone Activity" (PDF) (Technical Documentation). Environmental Protection Agency. August 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 16, 2020. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ "Tropical Cyclone History for Southeast South Carolina and Northern Portions of Southeast Georgia". National Weather Service Charleston, South Carolina. North Charleston, South Carolina: National Weather Service. January 9, 2021. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ a b c "1918 Hurricane NOT_NAMED (1918213N13302)". International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS) (Database). Asheville, North Carolina: University of North Carolina at Asheville. Retrieved August 15, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Landsea, Chris; Anderson, Craig; Bredemeyer, William; Carrasco, Cristina; Charles, Noel; Chenoweth, Michael; Clark, Gil; Delgado, Sandy; Dunion, Jason; Ellis, Ryan; Fernandez-Partagas, Jose; Feuer, Steve; Gamanche, John; Glenn, David; Hagen, Andrew; Hufstetler, Lyle; Mock, Cary; Neumann, Charlie; Perez Suarez, Ramon; Prieto, Ricardo; Sanchez-Sesma, Jorge; Santiago, Adrian; Sims, Jamese; Thomas, Donna; Lenworth, Woolcock; Zimmer, Mark (2008). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Metadata). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 1918/01 - 2008 REVISION. Retrieved August 15, 2023.

- ^ "Hurricanes Frequently Asked Questions". Atlantic Oceanographic & Meteorological Laboratory. Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. June 1, 2023. The Saffir-Simpson Scale. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Cline, Isaac (August 1918). "Louisiana Section" (PDF). Climatological Data. 23 (8). New Orleans, Louisiana: United States Weather Bureau: 59. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 15, 2023. Retrieved August 15, 2023 – via National Centers for Environmental Information.

- ^ "[Daily Weather Map Valid August 6, 1918 at 8 A.M.]" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: United States Weather Bureau. August 6, 1918. Retrieved August 15, 2023 – via NOAA Central Library.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Roth, David (April 8, 2010). "Louisiana Hurricane History" (PDF). Weather Prediction Center. pp. 30–31. Retrieved August 15, 2023.

- ^ a b c Schoner, R. W.; Molansky, S. (July 1956). "Storm of August 4–6, 1918". Rainfall Associated With Hurricanes (And Other Tropical Disturbances) (PDF). Washington, D.C.: National Hurricane Research Project. p. 103. Retrieved August 14, 2023 – via Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory.

- ^ Roth, David (March 15, 2023). "Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall. Camp Springs, Maryland: Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- ^ Bunnemeyer, Bernard (August 1918). "Texas Section" (PDF). Climatological Data. 23 (8). Houston, Texas: United States Weather Bureau: 87. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 15, 2023. Retrieved August 15, 2023 – via National Centers for Environmental Information.

- ^ "Twenty-Five Lost in Louisiana Hurricane". The Lima News. Lima, Ohio. August 7, 1918. p. 1. Retrieved May 7, 2017.

- ^ "Three Lives Lost". The Oshkosh Northwestern. Oshkosh, Wisconsin. August 7, 1918. p. 1. Retrieved May 7, 2017.

- ^ a b "City All But Wrecked". Natchez Democrat. Natchez, Mississippi. August 7, 1918. p. 1. Retrieved May 7, 2017.

- ^ "Million Dollar". Natchez Democrat. Natchez, Mississippi. August 7, 1918. p. 8. Retrieved May 7, 2017.

- ^ "Loss Will Exseed Million". Natchez Democrat. Natchez, Mississippi. August 7, 1918. p. 1. Retrieved May 7, 2017.

- ^ "Gerstner Aviation Field Almost Completely Blown Away". The Town Talk. Alexandria, Louisiana. August 7, 1918. p. 1. Retrieved May 7, 2017.