Windsor Hotel fire

| Windsor Hotel | |

|---|---|

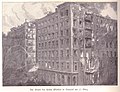

Windsor Hotel, before 1899 | |

| |

| General information | |

| Location | Manhattan, New York City |

| Opened | 1873 |

| Demolished | 1899 |

The Windsor Hotel fire occurred on March 17, 1899. The hotel located at 575 Fifth Avenue (at the corner of East 47th Street) in Manhattan, New York City, New York. The seven-story hotel opened in 1873,[1] at a time when hotel residency was becoming popular with the wealthy, and was advertised as "the most comfortable and homelike hotel in New York."[2][3] It burned down on St Patrick's Day 1899 with great loss of life.

Fire[edit]

-

Fire 1899

-

Fire 1899

On St Patrick's Day 1899, while people were gathered below to watch the parade, a fire destroyed the hotel within 90 minutes.[4] Supposedly the fire started when someone threw an unextinguished match out of a second-floor window and the wind blew it against the lace curtains.[5][6]

Dora Duncan, leading a dance class in the hotel at the time, managed to get her students, including her daughter, Isadora, to safety.[4] Abner McKinley, President McKinley's brother, who was outside when the alarm was raised, dashed in and rescued his wife and handicapped daughter.[6]

Firemen, some of them still in their dress uniforms from the parade,[5][7] made heroic rescues, but they were hampered by the crowds; the fire moved too fast for them to reach every window with ladders, and water pressure was inadequate.[2][8] Almost 90 people died (estimates vary), with numerous bodies landing on the pavement; some people fell when escape ropes burned their hands,[2] while some jumped in preference to being burned alive.[9] The operator of the hotel, Warren F. Leland, was unable to identify his 20-year-old daughter, Helen, who had jumped from the 6th floor.[2][4][10]

The following day The New York Times featured the headlines "Windsor Hotel Lies in Ashes" and "The Hotel a Fire Trap."[5][11] The fire commissioner, Hugh Bonner, blamed the construction of the hotel for the rapid spread of the fire: it did not have the cross walls that by 1899 were required by law.[12] According to some reports, the fire escapes soon became too hot to use;[5][7] other accounts state that there were none.[13][14] The Windsor Hotel fire was the inspiration for John Kenlon, who later became fire chief but was a lieutenant in 1899, to become one of the most forceful advocates of a high-pressure hydrant system in New York, which was finally installed in 1907.[8]

Aftermath[edit]

The bodies of 31 of the unidentified victims were buried in Kensico Cemetery in Valhalla, New York. A monument to them was dedicated on October 9, 2014.[15]

For a few months after the fire, the landowner, Elbridge Gerry, rented the site for billboards. In 1901, he built the Windsor Arcade, an ornamental building of luxury shops. It was torn down in the 1910s; the buildings that replaced it have also been demolished.[4][16] The two high-rises now occupying the site, at 565 and 575 Fifth Avenue,[17] have no plaque or marker for the tragedy.[2][4]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Friedman, Donald (2010). Historical Building Construction: Design, Materials, and Technology (second ed.). New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-73268-9., p. 224.

- ^ a b c d e Gray, Christopher (January 7, 2010). "A Day of Heroism and Horror". The New York Times.

- ^ For a picture of the hotel in 1877, see Edward B Watson and Edmund Vincent Gillon, New York Then and Now: 83 Manhattan Sites Photographed in the Past and in the Present, New York: Dover, 1976, ISBN 0-486-23361-8, p. 62.

- ^ a b c d e Gray, Christopher (Winter 2003). "Gotham Tragedy, Gotham Memory". City Journal.

- ^ a b c d "Windsor Hotel Lies in Ashes". The New York Times. March 18, 1899. p. 1. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ^ a b Golway, Terry (2003). So Others Might Live: A History of New York's Bravest: The FDNY from 1700 to the Present. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-02741-5., p. 1900, based on The New York Times.

- ^ a b Golway,p. 1901.

- ^ a b Robinson, Henry Morton (November 1928). "John Kenlon—Fire Fighter: How Modern Science Tames Smoke and Flames Is Revealed in the Amazing Experiences of New York City's Fearless Chief". Popular Science. pp. 36–38+. p. 38.

- ^ In City Journal, Gray quotes The New York Times: "At the fourth floor, Amelia Paddock, who had come in from Irvington just for a day of shopping, 'held out her arms to the crowd, then raised her hands as if calling for mercy on her soul. Then she clambered to the window sill, poised for an instant, and leaped, while a smothered groan went up from the crowd.'"

- ^ According to Appleton's Annual Cyclopaedia volume 4, p. 617, his wife was also killed and he died soon after, on April 4.

- ^ Wermiel, Sara E (2003). "No Exit: The Rise and Demise of the Outside Fire Escape". Technology and Culture. 44 (2): 258–284. doi:10.1353/tech.2003.0097. JSTOR 25148107. S2CID 108961041.

- ^ Golway, pp. 1901–02.

- ^ "The New York Hotel Fire," The Speaker March 25, 1899, volume 19, p. 340.

- ^ Robinson, pp. 37–38: "a veritable tinder box . . . no fire escapes, no standpipes, no fire buckets."

- ^ Risinit, Michael (October 7, 2014). "Kensico Cemetery honors victims of NYC hotel fire". The Journal News.

- ^ According to Watson and Gillon, p. 63, the 1921 S.W. Straus Building.

- ^ "575 Fifth Avenue". Emporis. Archived from the original on October 25, 2012.

- 1873 establishments in New York (state)

- Buildings and structures demolished in 1899

- Hotel buildings completed in 1873

- Hotels disestablished in 1899

- Defunct hotels in Manhattan

- Building and structure fires in New York City

- Burned hotels in the United States

- 1899 fires in the United States

- Hotel fires in the United States

- 1899 disasters in the United States

- 1899 in New York (state)

- Fifth Avenue

- Demolished buildings and structures in Manhattan

- Midtown Manhattan