Angela Morley

Angela Morley | |

|---|---|

Morley in 2004 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Walter Stott |

| Born | 10 March 1924 Leeds, West Riding of Yorkshire, England |

| Died | 14 January 2009 (aged 84) Scottsdale, Arizona, U.S. |

| Genres | Easy listening, classical, jazz, big band, film music |

| Occupation(s) | Composer, arranger, orchestrator, conductor |

| Instrument(s) | Alto saxophone, flute, clarinet, bass clarinet, piano |

| Years active | 1940–2008 |

| Website | www |

Angela Morley (born Walter Stott; 10 March 1924[1][2] – 14 January 2009[3]) was an English composer and conductor who became familiar to BBC Radio listeners in the 1950s under the name of Wally Stott. Morley notably provided incidental music for The Goon Show and Hancock's Half Hour. She attributed her entry into composing and arranging largely to the influence and encouragement of the Canadian light music composer Robert Farnon. Morley transitioned in 1972 and thereafter lived openly as a transgender woman.[3] Later in life, she lived in Scottsdale, Arizona.[4]

Morley won three Emmy Awards for her work in music arrangement. These were in the category of Outstanding Music Direction, in 1985, 1988 and 1990, for Christmas in Washington and two television specials starring Julie Andrews. Morley also received eight Emmy nominations for composing music for television series such as Dynasty and Dallas. She was twice nominated for an Academy Award in the category of Best Original Song Score: first for The Little Prince (1974), a nomination shared with Alan Jay Lerner, Frederick Loewe, and Douglas Gamley; and second for The Slipper and the Rose (1976), which Morley shared with Richard M. Sherman and Robert B. Sherman. She was the first openly transgender person to be nominated for an Academy Award.[5]

Early life and education[edit]

Morley was born in Leeds, Yorkshire[6] on 10 March 1924 under the name of Walter "Wally" Stott.[1][2][4][3] Morley's father was a watchmaker who played the ukulele-banjo, and the family lived above their jewellery shop.[6] Her mother also sang.[6] Morley was a fan of dance music before being able to read the labels on the records, listening notably to Jack Payne and Henry Hall as a child,[6] and began learning the piano at the age of eight on a Challen upright piano.[6] Morley's father died of angina[3] in 1933[4] at the age of 39, after which the family moved to Swinton and she ceased piano lessons.[6][3] She then tried playing violin at age 10 and the accordion at age 11, including in competitions, before choosing the clarinet and alto saxophone as primary instruments, taking clarinet lessons and playing in the school orchestra.[6] Morley then played in the semi-professional band led by Bert Clegg in Mexborough.[6]

As a mostly self-taught musician able to sight-read, Morley left school at age 15 to tour with Archie's Juvenile Band, earning a weekly wage of 10 shillings,[6] and also worked as a projectionist.[3] Her mentor at this time was the pianist Eddie Taylor.[6] Morley continued to play saxophone in British dance bands during the period of World War II, joining the Oscar Rabin Band as lead alto in 1941, at age 17.[6] With this band, she began writing arrangements for pay[6] and made a recording debut with the tracks "Waiting for Sally" and "Love in Bloom".[4] She later joined Geraldo's band, which performed for BBC Radio several times a week,[6] in 1942[1][7] or 1944.[2][6][4] With Geraldo's band Morley gained experience arranging for bands of many sizes and styles.[6] She studied harmony and musical composition in London with the British-Hungarian composer Mátyás Seiber and conducting with the German conductor Walter Goehr.[6] Morley's early work was also influenced by Robert Farnon and Bill Finegan.[2]

Career[edit]

Pre-transition work[edit]

At the age of 26, Morley stopped playing in bands to instead work solely as a writer, composer, and arranger,[6] and would go on to work in recording, radio, television, and film.[1] She was originally a composer of light music[2] or easy listening,[3] best known for pieces such as the jaunty "Rotten Row" and "A Canadian in Mayfair", the latter dedicated to Robert Farnon.[4] Morley also worked with the Chappell Recorded Music Library and Reader's Digest.[4][6]

Morley is known for writing the theme tune, with its iconic tuba partition, and incidental music for Hancock's Half Hour in both its radio and television incarnations,[1][2][8] and was also the musical director for The Goon Show from the third series in 1952 to the last show in 1960, conducting the BBC Dance Orchestra.[2] At this time, she was known to work quickly and would sometimes write music for The Goon Show the same day of recording,[1] which consisted of two full-band arrangements per week and incidental music.[7] Another short but remembered theme composed by Morley was the 12-note-long "Ident Zoom-2", written for Lew Grade's Associated TeleVision (ATV), in use from the introduction of colour television in 1969, until the demise of ATV in 1981. By 1953, Morley was also scoring films for the Associated British Picture Corporation under music director Louis Levy.[6]

In 1953, Morley became musical director for the British section of Philips Records,[1][2][3] arranging for and accompanying the company's artists alongside producer Johnny Franz. She notably worked with Frankie Vaughan on "The Garden of Eden" in 1957.[4] In 1958, she began an association with Welsh singer Shirley Bassey, including work for Bassey's recordings of "The Banana Boat Song" (1957), "As I Love You" (1958), which reached no. 1 in the UK Singles Chart in January 1959,[3] and "Kiss Me Honey Kiss Me" (1958).[4] She was the head of an orchestra and a chorale at this time, releasing records as "Wally Stott and His Orchestra" and "The Wally Stott Chorale" respectively.[3] She also worked with artists such as Noël Coward and Dusty Springfield[7] and on the first four solo albums by Scott Walker.[2][9] The next hits she worked on were Robert Earl's "I May Never Pass this Way Again" and Frankie Vaughan's "Tower of Strength".[4] In 1962 and 1963, Morley arranged the United Kingdom entries for the Eurovision Song Contest, "Ring-A-Ding Girl" and "Say Wonderful Things", both sung by Ronnie Carroll.[4] The former was conducted on the Eurovision stage in Luxembourg. She was also credited with a rhythmic drum solo in the 1960 horror film Peeping Tom, which a dancer plays on a tape recorder.[2][10]

In 1961, Morley provided the orchestral accompaniments for a selection of choral arrangements made by Norman Luboff for an RCA album that was recorded in London's Walthamstow Town Hall. The New Symphony Orchestra (an ad hoc recording ensemble, not to be confused with the Bulgarian New Symphony Orchestra), was conducted by Leopold Stokowski, and the professional British choir, namely the Ambrosian Singers as rehearsed by Luboff, performed such favourites as "Deep River", Handel's "Largo", Bach's "Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring", Rachmaninoff's "Vocalise", under the album's title Inspiration (also later reissued on a BMG Classics CD). In 1962, she arranged and conducted the RCA Red Seal debut album Romantic Italian Songs for Italian-born tenor Sergio Franchi, and later did the arrangements and conducting for Franchi's 1963 RCA album, Women in My Life.

Some of her other notable works in the years before transitioning include the composition and arrangement for the films The Looking Glass War, released in 1970,[1][10] and When Eight Bells Toll, released in 1971.[1][10] She stepped back from the music and film industry between 1970 and 1972[3] in order privately to undergo gender transition.[7] During this time, Morley studied clarinet chamber music at the Watford School of Music for eighteen months.[3]

After transitioning to living publicly as a woman in 1972,[3] Morley continued to work in music, now using the name Angela Morley professionally. Due to worries about how she would be received publicly as a transgender woman, she declined opportunities to appear on television, such as on The Last Goon Show of All in 1972, though she continued to work with many of her previous colleagues.[1] Because of the scrutiny she might face, she had to be persuaded by Franz to continue conducting .[3] One of her first projects upon her return to public life was as an orchestrator on Jesus Christ Superstar. She then orchestrated, arranged, and aided in the composition of the music for the final musical film collaboration of Lerner and Loewe, The Little Prince, released in 1974.[1][10] Her contribution to the film was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Original Music, Scoring Original Song Score and/or Adaptation[2][11] and she travelled to California for the award ceremony.[6]

Morley was also the composer, conductor, arranger and orchestrator for the Sherman Brothers' musical film adaptation of the Cinderella story, The Slipper and the Rose: The Story of Cinderella in 1976, however she was only credited as conductor and arranger.[12] She was again nominated for the Academy Award for Best Original Music, Original Song Score and Its Adaptation or Best Adaptation Score for this film along with the Sherman Brothers[2][13] and again was present at the award ceremony.[6] Though initially reluctant, citing lack of preparation and unfamiliarity with the novel, Morley wrote most of the score for the animated Watership Down film, released in 1978.[1] She had to work quickly based on work drafted by Malcolm Williamson, then Master of the Queen's Music, who left the project.[1][2][14] At this time, she was a regular guest conductor of the BBC Radio Orchestra[2] and BBC Big Band.

Work in the United States[edit]

Following the success of Watership Down, Morley lived for a time in Brentwood, Los Angeles, where she began working for Warner Bros.[6] She permanently relocated to Los Angeles in 1979[3] and began working primarily on American television soundtracks, including those of Dynasty, Dallas, Cagney & Lacey, Wonder Woman[1], and Falcon Crest,[2] working with the music departments of major production companies, including Warner Bros., Paramount Pictures, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Universal Pictures and 20th Century Fox Television.[6]

Thanks to a mutual friend, Herbert W. Spencer, Morley collaborated with John Williams throughout the 1970s and 1980s, arranging for the Boston Pops Orchestra under Williams' direction and working on films such as Star Wars, Superman, The Empire Strikes Back, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, Hook, Home Alone, Home Alone 2: Lost in New York, and Schindler's List,[6][15] though in an uncredited capacity.[10] She also collaborated with André Previn,[7] Lionel Newman,[7] Miklós Rózsa,[2][7] and Richard Rodney Bennett.[2] Later, she would work with soloists such as Yo-Yo Ma and Itzhak Perlman.[7] She was nominated six times for Emmy Awards for composing[2] and won three times for music direction,[2] notably of two Julie Andrews television specials.[16]

Morley continued to work in television until 1990.[2] She relocated again to Scottsdale, Arizona in 1994, where she recorded two CDs with the John Wilson Orchestra.[4] She also lectured at the University of Southern California on film scoring[4] and founded the Chorale of the Alliance française of Greater Phoenix.[6] Her last film credit was for the Disney film The Hunchback of Notre Dame II in 2002, where she worked as an additional orchestrator and composer of additional music.[10]

Personal life[edit]

Morley was a transgender woman and began transitioning to live openly as a woman in 1970, at the age of 46.[1] According to her friend and colleague Max Geldray, she struggled with her gender identity throughout her life,[1][3] and according to her wife, Christine Parker, Morley probably tried hormone replacement therapy at some point before they met.[3] Morley underwent sex reassignment surgery in Casablanca in June 1970 and publicly came out as a woman in 1972.[3][Footnotes 1] She chose the new surname Morley as it was her grandmother's maiden name.[2][3]

Morley was twice married.[2] Her first wife, Beryl Stott, was a singer and choral arranger who founded the Beryl Stott Singers, also known as the Beryl Stott Chorus or Beryl Stott Group.[2][3] Beryl Stott died prior to Morley's gender transition.[1][7] Morley met Christine Parker, also a singer, in London,[3] and they married on 1 June 1970.[2] Parker was a major support to Morley through her transition. Morley stated that: "It was only because of her love and support that I then was able to deal with the trauma, and begin to think about crossing over that terrifying gender border."[1][2][3]

The couple moved to Los Angeles in 1979 following the success of Watership Down, and owned a house in the San Fernando Valley.[3] They moved to Scottsdale, Arizona in 1994.[4] As of November 2015[update], Parker was still living in Scottsdale.[1]

Morley had two children with her first wife Beryl Stott: a daughter, Helen, who predeceased her in 1986, and a son, Bryan,[3] who was living as of January 2009[update].[2][7][17] She also had grandchildren and great-grandchildren at the time of her death.[17]

Morley had many friendships with fellow musicians and industry colleagues. While working on The Goon Show, she made the acquaintance of Peter Sellers, and would eventually share fond memories of him to his biographer Ed Sikov.[2] She and Max Geldray continued to be good friends following her transition.[2] She also noted that she was lifelong friends with Herbert W. Spencer from 1955, while working on Gentlemen Marry Brunettes, until his death in 1992.[3]

Death[edit]

Morley died in Scottsdale, Arizona[4] on 14 January 2009 at the age of 84.[1][2][3][17] Her death was a result of complications of a fall and a heart attack.[17] Her death was almost exactly 50 years since her no. 1 hit with Shirley Bassey, "As I Love You".[3]

Legacy[edit]

Morley's talent was noted by many of her peers. Arranger Tony Osborne said that she was "at the top of the range [...] second only to Robert Farnon, and it was a pretty close run thing at that", while Scott Walker compared working with Morley to working with Frederick Delius.[4]

Morley was interviewed for the biography of her Goon Show colleague Peter Sellers by his biographer Ed Sikov prior to the book's publication in 2002.[3] When asked by Sikov how she should be identified in the book, she told him: "It's a judgement you'll have to make and I'll have to accept".[3] Sikov chose to refer to her as Wally Stott in the context of her past work but as Angela Morley in the present;[3] most posthumous writing about her follows a similar pattern.[1][2][4][3][7]

In 2015, BBC Radio 4 produced a radio drama about Morley, 1977, which was written by Sarah Wooley.[18][19] 1977 is a semi-fictional account of the year in which Morley was enlisted to complete composition of the musical soundtrack to the film Watership Down in three weeks, after Master of the Queen's Music Malcolm Williamson left the project.[1] The radio drama, starring Rebecca Root, was rebroadcast in 2018.[18]

Morley's work has been compared to that of Wendy Carlos, given that they were both transgender women composing film scores in the same time period, though they never met; notably, the composer and researcher Jack Curtis Dubowsky analysed and compared their careers and styles in a chapter of his book Intersecting Film, Music, and Queerness.[3] As a prominent and early transgender woman working in film, Morley has also been compared to trans women in the film industry who came out in later years, such as Lana Wachowski.[3] In this vein, the film scholar Laura Horak promotes a broader view of the term "filmmaker" when it comes to transgender and gender variant individuals in film history,[20] noting that:

Most of the time, making films and videos is a collaborative endeavour. Despite the many creative contributions of writers, cinematographers, producers, editors, actors, and others, we too often credit films to the director alone. This habit fundamentally misrepresents the filmmaking process, as film scholars Berys Gaut and C. Paul Sellors have argued. If we want to trace a history of trans and gender variant people's audiovisual creativity, we should look for them both in and beyond the director's chair.

— Laura Horak, Tracing the History of Trans and Gender Variant Filmmakers, p. 10

Horak includes Morley among her selected list of trans and gender variant filmmakers as a composer, noting in particular her work on The Little Prince and Watership Down alongside the film works of other transgender and gender variant people in Classical Hollywood cinema such as Dorothy Arzner and Christine Jorgensen.[20]

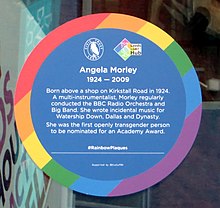

Morley is commemorated by a Rainbow Plaque placed by Leeds Pride at the entrance to the BBC Leeds building,[21] and also by a blue plaque at her birthplace in Kirkstall.[22]

Genre[edit]

Morley's work was influenced by a number of genres and styles. She initially played in British dance bands, and spent much of her career composing music that was labelled as light and easy listening, as well as film scores and television soundtracks. Light music and easy listening were generally not taken seriously or given much respect at the time that Morley was composing,[3] which Dubowsky credits partially to misogyny, due to the genre's association with femininity.[3] Dubowsky acknowledges that the genre has been seen as derivative, bourgeois, and (in America) racially exclusionary, but calls for the genre and Morley's work to be reconsidered for its influence on film music and the technical skill required in its production.[3] He also, in the conclusion to his chapter on Morley and Wendy Carlos, questions whether Morley was drawn to light music for its perceived feminine qualities.[3]

Beyond her light and easy listening work, Morley collaborated with many kinds of artists at Philips Records, from folk music to rock and roll, produced her own recordings of music from Christmas music to show tunes,[3] and later focused her attention on orchestral, classical and choral arrangements that went beyond the scope of light music and easy listening.[6]

Morley credited her eventual turn away from film scores to technological changes: tape recording, new types of microphones, and the advent of stereophonic sound had reached the wider music industry, but not film.[6] She wrote that "to go to a cinema to hear one's latest score was absolute torture."[6] Nevertheless, she continued to work intermittently in film until 2002.[10]

Characteristics of her compositions[edit]

Her music for The Goon Show stood out as having "a jazz flavour, rather than the standard comedy-show music of that time."[2] From some of her earliest composition works, Morley used instruments to represent characters, such as the tuba notes in the theme to Hancock's Half Hour which represented Tony Hancock.[2] While Morley was working with Johnny Franz at Philips Records, Robert Earl noted that Morley and Franz "didn't believe in fade-out endings so all those ballads end on big notes".[4]

Her work on film scores is noted for her "mastery of orchestration and gift for evoking moods and atmospheres" (in reference to The Slipper and the Rose and Watership Down)[7] and "her strengths in swing, classical, and romantic period styles" (in reference to Watership Down).[3] For Watership Down, Morley created a character theme for Kehaar, voiced by Zero Mostel.[3] On "Kehaar's Theme", Dubowsky notes the influence of Claude Debussy and comments that:

For this theme, Morley takes a fragment of the opening flute motive of Debussy's 'Prélude à l'après midi d'un faune' [...] and spins it into a majestic, soaring, romantic swing waltz, an amalgamation of her work in French romantic style orchestral scoring and big band swing. Alto sax takes the tune; the surrounding orchestration has a rich, symphonic, romantic, classical Hollywood sound, not unlike the orchestrations Morley did for John Williams. In addition to this mastery of style and technique, the opening I–bVI progression is fresh and contemporary; the 'borrowed' bVI chord had been used in earlier psych rock but would become prominently featured in the 'new wave' popular music of the time. [...] Morley's handling of 'Kehaar's Theme' and its orchestral accompaniment shows a technique well honed not just from film work, but from years of working in 'light music' where romantic accompaniments and swing tunes were frequently employed. While not an 'easy listening' version of Debussy, 'Kehaar's Theme' nevertheless suggests how one might conceive of such a thing and execute it with finesse.

— Jack Curtis Dubowsky, Intersecting Film, Music, and Queerness, p. 125-126

He also notes that "Kehaar's Theme" incorporates polyrhythms and has an emphasis on string instruments, and that it draws from many of the genres Morley worked in: "classical, swing, jazz, light music, concert music, and film scoring".[3] Speaking more broadly about the Watership Down score, Dubowsky also notes the effectiveness of "Violet's Gone" and "Venturing Forth".[3]

Selected discography[edit]

Credited as Wally Stott[edit]

As leader[edit]

- Great American Show Tunes (1953), Epic

- There's No Business Like Show Business (1954), Epic

- A Merry Christmas (1958), Philips

- Music of the City....London under Columbia (1958), Philips (also released as London Pride and London Souvenir (A Musical Souvenir Of London Town) by Philips in the UK)

- Christmas in Stereo (1959), Warner Bros. (Christmas by the Fireside in the UK)

- Max Steiner's Complete Original Score Gone With The Wind (1967), Pickwick, conducting the London Symphonia

Contributing work[edit]

- Shirley Bassey, Love For Sale (1968), Philips (as arranger)

- Roy Castle, Castlewise (1961), Philips (as arranger)

- Noël Coward, I'll See You Again (1954), Philips (as arranger)

- Diana Dors, Swingin Dors (1960), Pye (as arranger)

- Roy Castle, Castlewise (1961), Philips (as arranger)

- Robert Earl, Robert Earl Showcase (1959), Philips (as arranger)

- Susan Maughan, Sentimental Susan (1964), Philips (as arranger)

- St. Paul's Choir, The Sounds of Christmas (1971), Golden Hour (co-billing)

- Harry Secombe, Film Favourites (1964), Philips (as arranger)

- Harry Secombe, Christmas Cheer (1966), Philips (as arranger) (also released as White Christmas)

- Harry Secombe, Italian Serenade (1966), Philips (as arranger)

- Anne Shelton, Songs from the Heart (1958) Philips

- Scott Walker, Scott (1967), Philips (as arranger)

- Scott Walker, Scott 2 (1969), Philips (as arranger)

- Scott Walker, Scott 3 (1969), Philips (as arranger)

- Spellbound (2008), Vocalion Records (reissue)

Credited as Angela Morley[edit]

- The Slipper and the Rose (1976), MCA Records/EMI Records

- Watership Down (1978), CBS Records

- Soft Lights and Sweet Music: the Scores of Angela Morley (2001), Vocalion Records

- The Film and Television Music of Angela Morley (2003), Vocalion Records

- The Bad and the Beautiful (1952), Arranger

Selected filmography[edit]

- The Heart of a Man (1959)

- The Lady Is a Square (1959)

- Peeping Tom (1960). Credited for the drum solo played on a tape-recorder during a dance routine.

- The Looking Glass War (1970)

- Captain Nemo and the Underwater City (1969)

- When Eight Bells Toll (1971)

- The Little Prince (1974) – Oscar nomination

- The Slipper and the Rose (1976) – Oscar nomination

- Watership Down (1978)

Awards and honours[edit]

Awards[edit]

- 1985: 37th Primetime Emmy Awards - Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Music Direction for Christmas in Washington (with Ian Fraser and Billy Byers)[10]

- 1988: 40th Primetime Emmy Awards - Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Music Direction for Julie Andrews: The Sound of Christmas (with Ian Fraser, Chris Boardman, and Alexander Courage)[10]

- 1990: 42nd Primetime Emmy Awards - Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Music Direction for Julie Andrews in Concert (Great Performances) (with Ian Fraser, Billy Byers, Chris Boardman, Bob Florence, and J. Hill)[10]

Nominations[edit]

- 1975: 47th Academy Awards - Academy Award for Best Scoring: Original Song Score and Adaptation or Scoring: Adaptation for The Little Prince (with Alan Jay Lerner, Frederick Loewe, and Douglas Gamley)[10]

- 1978: 50th Academy Awards - Academy Award for Best Original Song Score and Its Adaptation or Adaptation Score for The Slipper and the Rose: The Story of Cinderella (with Robert B. Sherman and Richard M. Sherman)[10]

- 1980: 32nd Primetime Emmy Awards - Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Music Direction for The Big Show episode "Steve Lawrence and Don Rickles" (with Nick Perito, Joe Lipman, and Peter Myers)[10]

- 1984: 36th Primetime Emmy Awards - Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Music Composition for a Series for Emerald Point N.A.S. episode "The Homecoming"[10]

- 1985: 37th Primetime Emmy Awards - Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Music Composition for a Series for Dynasty episode "Triangles"[10]

- 1986: 38th Primetime Emmy Awards - Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Music Composition for a Series for Dynasty episode "The Subpoenas"[10]

- 1987: 39th Primetime Emmy Awards - Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Music Composition for a Series for Dallas episode "A Death in the Family"[10]

- 1987: 39th Primetime Emmy Awards - Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Music Direction for Liberty Weekend: Opening Ceremonies (with Ian Fraser, Chris Boardman, Ralph Burns, Alexander Courage, and J. Hill)[10]

- 1988: 40th Primetime Emmy Awards - Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Music Composition for a Series for Dallas episode "Hustling"[10]

- 1989: 41st Primetime Emmy Awards - Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Music Composition for a Series for Blue Skies episode "The White Horse"[10]

See also[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Dubowsky (2016) notes and attempts to correct inconsistencies in the circumstances surrounding Beryl Stott's death and Morley's transition that were reported in various obituaries at the time of her death. His facts are based on personal correspondence with Christine Parker.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v "Writing '1977' for BBC Radio 4, and why it's about so much more than 'a transgender woman in the 1970s'". BBC. 30 November 2015. Archived from the original on 7 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af "Angela Morley Obituary". The Guardian. London. 23 January 2009. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap Dubowsky, Jack Curtis (2016). "Chapter 4: A Tale of Two Walters: Genre and Gender Outsiders". Intersecting Film, Music, and Queerness. Basingstoke UK; New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 105–130. ISBN 978-1-349-68713-8. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "Angela Morley: Composer and arranger who worked with Scott Walker and scored 'Dynasty' and 'Dallas'". Obituaries. The Independent. 22 January 2009. Archived from the original on 18 June 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ Betancourt, Manuel (20 January 2016). "Angela Morley: The Story Behind the Two-Time Oscar-Nominated Trans Composer". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab "Career Autobiography of Angela Morley". www.angelamorley.com. Archived from the original on 15 September 2008. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l ."Angela Morley". The Daily Telegraph. London. 25 January 2009. Archived from the original on 2 May 2019. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- ^ Stevens, Christopher (2010). Born Brilliant: The Life of Kenneth Williams. John Murray. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-84854-195-5.

- ^ "BBC Wales – Music – Shirley Bassey – "As I Love You"". Archived from the original on 12 January 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t "Angela Morley". IMDb. Archived from the original on 14 December 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ The Little Prince - IMDb, archived from the original on 12 July 2009, retrieved 30 March 2020

- ^ The Slipper and the Rose: The Story of Cinderella (1976) - IMDb, archived from the original on 30 March 2016, retrieved 30 March 2020

- ^ The Slipper and the Rose: The Story of Cinderella - IMDb, archived from the original on 29 August 2011, retrieved 30 March 2020

- ^ "How the music score for the 1978 feature film Watership Down came together" Archived 8 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Angela Morley's website, retrieved 26 March 2018.

- ^ "Angela Morley". IMDb. Archived from the original on 14 December 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ "Emmy Winning and Oscar Nominated Arranger Angela Morley Passes Away at 84", Broadway World, 18 January 2009, archived from the original on 27 August 2009, retrieved 24 January 2009

- ^ a b c d "Emmy Winning and Oscar Nominated Arranger Angela Morley Passes Away at 84". BroadwayWorld.com. Archived from the original on 8 December 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ a b "Drama: 1977" Archived 10 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine. BBC online, 3 December 2015.

- ^ "Sarah Wooley, writer for radio, TV, film, theatre" Archived 26 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Wooley's website, retrieved 26 March 2018.

- ^ a b Horak, Laura (2017). "Tracing the History of Trans and Gender Variant Filmmakers". The Spectator. 37 (2): 9–20.

- ^ "The Rainbow Plaque Trail" (PDF). Leeds Civic Trust. 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ "Goon but not forgotten - a blue plaque for Leeds musician Angela Morley". Yorkshire Post. Leeds. 15 June 2017. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

External links[edit]

- 1924 births

- 2009 deaths

- 20th-century classical composers

- 20th-century English composers

- 20th-century saxophonists

- Deaths from falls

- English classical saxophonists

- English emigrants to the United States

- English film score composers

- English music arrangers

- English jazz saxophonists

- Eurovision Song Contest conductors

- LGBT people from Yorkshire

- British light music composers

- Musicians from Leeds

- Primetime Emmy Award winners

- British women classical composers

- Women film score composers

- English LGBT composers

- English transgender women

- Transgender composers

- Transgender women musicians

- Women saxophonists

- 20th-century English women musicians

- 20th-century conductors (music)

- 20th-century British women composers

- 20th-century English LGBT people

- 21st-century English LGBT people

- The Goon Show

- English television composers