User:Plb40/sandbox

Expectancy violations theory or EVT, is a theory of communication that analyzes how individuals respond to unanticipated violations of social norms and expectations.[1] Judee Burgoon founded the theory in the late 1970s as "nonverbal expectancy violations theory" in her research on individuals' expectations of others' nonverbal behavior and how they react to the violation of those expectations. The theory was later changed to its current name when other researchers began to focus on expectancy violations beyond nonverbal communication. What one can infer from these definitions is that expectancy violation is a breach or violation of an individual's prediction. This theory sees communication as the exchange of information that is high in relational content and can be used to violate the expectations of another who will perceive the exchange either positively or negatively, depending upon the liking between the two people.[2][3][4][5] Expectancies are primarily based upon social norms and specific characteristics of the communicators.[6] Such expectancies can come directly from the current interaction but are often formed by a person's initial stance determined by a blend of person requirements (biological/survival needs), expectations (normative schemata) and desires (likes and dislikes) or 'RED'. This is known as a person's interaction position (IP).[7][8] Violations of expectancies cause arousal and compel the recipient to initiate a series of cognitive appraisals of the violation.[9] The theory proposes that expectancy will influence the outcome of the communication as positive or negative and predicts that positive violations increase the attraction of the violator and negative violations decrease the attraction of the violator.[4]

History[edit]

Early History[edit]

Expectancy Violations Theory has its roots in Uncertainty Reduction research developed by Charles R. Berger [10] which attempts to predict and explain how communication is used to reduce the uncertainty among people involved in conversations with one another the first time they meet.

Early communication research that led to EVT was conducted by Judee K. Burgoon in 1976 from her Nonverbal Expectancy Violations Model.[11] It explored issues of personal space and how communicative functions could be seen through expectations and expectation violations. In its earliest form, the theory focused on how people react to violations of personal space. Later however, the theory was extended to encompass all types of behavior violations.[12] Whereas much of Burgoon's work emphasizes nonverbal violations of physical space, also known as the study of proxemics.

Expectancy Violations Theory development[edit]

Expectancy Violations Theory builds on this theory in understanding Proxemics further. Guerrero and Anderson propose that an unexpected behavior during interpersonal communication causes arousal and uncertainty in people; people then look to explain the violation in order to better predict another’s behavior.[13]

In relation to Burgoon's Proxemics Theroy, a large percentage of the attention has being paid to personal space norms recognizing a gap in research regarding the use of space as communication. Her theory brings to light another new component: kinesics. This is the study of body movements, gestures and facial expressions as a means of communication.[14] Also, the communicator, or violator, has a degree of power either in the present situation or a possible future one that influences the interpretation of his/her actions. The theory was later applied to other forms of nonverbal behaviour and subsequently to other acts of communication, This is now referred to as EVT. It is considered a theory of communication processes, and more specifically a theory of discourse and interaction.

Recent Advancements[edit]

Recently, this theory has undergone some reconstitution by Burgoon and her colleagues and has resulted in a newly proposed theory known as Interaction Adaptation Theory,[15] which is a more comprehensive explanation of adaptation in interpersonal interaction.[16]

Core Concepts of Expectancy Violations Theory[edit]

The three core concepts of Expectancy Violations Theory are Expectancy, Violation Valence and Communicator Reward Valence.[17]

Expectancy[edit]

An example of an Expectancy Violation is how close you allow people to approach you before the distance you expect them to approach to within is violated. For example a friend would be allowed to approach you closer than a member of the public. On the other end of the scale, you expect in a relationship that the personal space is more intimate.[18]

According to the expectancy violation theory, three core factors affect expectancies, these are; communicator characteristics, relational characteristics and context. Communication characteristics are individual differences, including age, sex, ethnic background, and personality traits. For instance, you might expect an elderly woman to be more polite than an adolescent boy based on perceptions.[19]

Expectancy refers to what an individual anticipates will happen in a given situation. Expectancy violations refer to the actions which sufficiently discrepant from the expectancy that is noticeable and classified as outside the expectancy range. In psychology such behaviour is frequently referred to as behavioural dis-confirmation.[20]

Behavioural expectations may also shift depending on the environment you are experiencing for example visiting a church will produce different expectations than being in a social function. The violations you expect will therefore be altered. Similarly expectations differ based on culture. For example, you may expect someone to greet you by kissing your face three times on alternating cheeks if you are in parts of Europe, but not if you are in the United States.[21]

Communicator Reward Valence[edit]

The communicator reward valence is an evaluation you make about the person who committed the violation. Em Griffin summarises the concept behind Communicator Reward Valence as the sum of positive and negative attributes brought to the encounter plus the potential to reward or punish in the future.[22] More specifically, does this person have the ability to reward or punish you in the future? If so, then the person has a positive reward valence. Rewards simply refer to this person’s ability to provide you with something you want or need.

By examining the context, relationship, and communicator’s characteristics, individuals arrive at a certain expectation for how a given person should and will likely behave. Changing even one of these expectancy variables might lead to a different expectation.[23]

Violation Valence[edit]

Violation Valence is the perceived positive or negative value assigned to a breach of expectations, Regardless of who the violator is.[24] Once you have determined,that someone’s behaviour was, in fact, a breach of expectation, you then judge the behaviour in question. This breach is known as the violation valence—the positive or negative evaluation you make about a behaviour that you did not anticipate. The difference between the negative violation and the negative confirmation do not appear significant. Dis-confirmations tend to intensify the outcomes,especially in the positive violation condition.[25]

Theoretical viewpoints and assumptions[edit]

Needs for personal space and affiliation[edit]

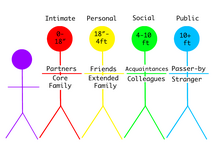

Expectancy Violations Theory builds upon a number of communication axioms.[26] EVT assumes that humans have two competing needs; a need for personal space, and a need for affiliation.[26][2] Specifically, humans all need a certain amount of personal space, also thought of as distance or privacy.[2] People also desire a certain amount of closeness with others, or affiliation.[26] EVT seeks to explain 'personal space', and the meanings that are formed when expectations of appropriate personal space are infringed or violated.[26] According to anthropologist Edward Hall, the zone of personal space includes: Intimate Distance (0-18 inches), Personal Distance (18 inches-4 feet), Social Distance (4–10 feet), and Public Distance (10 feet to infinity).[27]

Another feature of personal space is Territoriality. Territoriality refers to behavior which "is characterized by identification with a geographic area in a way that indicates ownership" (Hall, 1966).[28] In humans, territoriality refers to an individual's sense of ownership over physical items, space, objects or ideas, and defensive behavior in response to territorial invasions.[28] Territoriality is made up of three territory types: Primary Territories, Secondary Territories and Public Territories.[29] Primary territories are considered exclusive to an individual.[28] Secondary territories are objects, spaces or places which "can be claimed temporarily" (Hall, 1966), but are neither central to the individual's life nor are exclusively owned.[28] Public territories are "available to almost anyone for temporary ownership".[28] Territoriality is frequently accompanied by prevention and reaction.[30] When an individual perceives one of their needs has been compromised, EVT predicts that they will react. For instance, when an offensive violation occurs, the individual tends to react as though protecting their territory.

Beyond explaining individuals’ physical space and privacy needs, EVT also makes specific predictions as to how individuals will react to a given violation. Will an individual reciprocate or match someone’s unexpected behavior, or will that individual compensate or counteract by doing the opposite of that person's behavior? Before making a prediction about reciprocation or compensation, however, you must evaluate EVT's three core concepts: expectancy, violation valence, and communicator reward valence.[26][27]

Expectancies are learned and drive human interaction[edit]

Burgoon (1978) notes that people do not view others' behaviors as random; rather, they have various expectations of how others should think and behave. EVT proposes that observation and interaction with others leads to expectancies. The two types of expectancies noted are predictive and prescriptive.[31] Predictive expectations are "behaviors we expect to see because they are the most typical" (Houser, 2005), and vary across cultures.[31] They let people know what to expect based upon what typically occurs within the context of a particular environment and relationship.[27] For example, a husband and wife may have an evening routine in which the husband always washes the dishes. If he were to ignore the dirty dishes one night, this might be seen as a predictive discrepancy. Prescriptive expectations, on the other hand, are based upon "beliefs about what behaviors should be performed" and "what is needed and desired" (Houser, 2005).[31]

Furthermore, according to EVT, three factors influence a person’s expectations: interactant variables, environmental variables, and variables related to the nature of the interaction.[32] Interactant variables are the traits of those persons involved in the communication, such as sex, race, culture, status, and age.[32] Environmental variables include amount of space available and nature of the territory surrounding the interaction. Interaction variables include social norms, purpose of the interaction, and formality of the situation.[32] As the theory evolved, these factors also evolved into communicator characteristics, relational characteristics, and context.[27] Communicator characteristics include personal features such as an individual's appearance, personality and communication style.[27] It also includes factors such as age, sex and ethic background.[27][33] Relational characteristics refers to factors such as similarity, familiarity, status and liking also influence an individual's expectations.[27] The type of relationship one individual shares within another (e.g. romantic, business or platonic), the previous experiences shared between the individuals, and how close they are with one another are also relational characteristics that influence expectations.[33] Context encompasses both environment and interaction characteristics.[33]

Communicator reward valence[edit]

Individuals seek to reward others and seek to avoid punishing others, as explained by Social Exchange Theory.[34] When one individual interacts with another, Burgoon believes he or she will assess the "positive and negative attributes that person brings to the encounter".[27] In addition to this, they will also the encounter's potential for rewards or losses.[27] The term 'communicator reward valence' is used to describe the results of this assessment.[27] For example, people will feel encouraged during conversation when the listener is nodding, making eye contact and responding actively. Conversely, if the listener is avoiding eye contact, yawning and texting, it is implied they have no interest in the interaction and the speaker may feel violated.

Violation valence[edit]

The term 'arousal value' is used to describe the consequences of deviations from expectations. When an individual's expectations are violated, their interest or attention is aroused.[27] When arousal occurs, one's interest or attention to the deviation increases and one pays less attention to the message and more attention to the source of the arousal.[35]

Behavior violations arouse and distract, calling attention to the qualities of the violator and the relationship between the interactants.[36] A key component to EVT is the notion of violation valence, or the association the receiver places on the behavior violation.[37] A violatee’s response to an expectancy violation can be positive or negative and is dependent on two conditions: positive or negative interpretation of the behavior and the nature (rewardingness) of the violator. Rewardingness of the violator is evaluated through many categories – attractiveness, prestige, ability to provide resources, or associated relationship. For instance, a violation of one’s personal space might have more positive valence if committed by a wealthy, powerful, physically appealing member of the opposite sex than a filthy, poor, homeless person with foul breath. The evaluation of the violation is based upon the relationship between the particular behavior and the valence of the actor.[36]

After assessing expectancy, violation valence, and communicator reward valence of a given situation, it becomes possible to make rather specific predictions about whether the individual who perceived the violation will reciprocate or compensate the behavior in question. Guerrero (1996) and Burgoon (2000) noticed that predictable patterns develop when considering reward valence and violation valence together.[38] Specifically, if the violation valence is perceived as positive and the communicator reward valence is also perceived as positive, the theory predicts you will reciprocate the positive behavior. For example, your boss gives you a big smile after you have given a presentation. Guerrero and Burgoon would predict that you would smile in return. Similarly, if you perceive the violation valence as negative and perceive the communicator reward valence as negative, the theory again predicts that you reciprocate the negative behavior. Thus, if a disliked coworker is grouchy and unpleasant towards you, you will likely reciprocate and be unpleasant in return.

Conversely, if you perceive a negative violation valence but view the communicator reward valence as positive, it is likely that you will compensate for your partners negative behavior. For example, one day your boss appears sullen and throws a stack of papers in front of you. Rather than grunt back, EVT that you will compensate for your boss’ negativity, perhaps by asking if everything is OK (Guerrero & Burgoon, 1996). More difficult to predict, however, the situation in which someone you view as having a negative reward valence violates you with a positive behavior. In this situation, you may reciprocate, giving the person the “benefit of the doubt.”.[26]

The above assumptions and discussion can be summarized into six major propositions posited by Expectancy Violations Theory:[39]

- People develop expectations about verbal and nonverbal communication behavior from other people.

- Violations of these expectations cause arousal and distraction, further leading the receiver to shift his or her attention to the other, the relationship, and meaning of the violation.

- Communicator reward valence determines the interpretation of ambiguous communication.

- Communicator reward valence determines how the behavior is evaluated.

- Violation valences are determined by three factors: (1) the evaluation of the behavior, (2) whether or not the behavior is more or less favorable than the expectation, and (3) the magnitude of the violation. A positive violation occurs when the behavior is more favorable than the expectation. A negative violation occurs when the behavior is less favorable.

- Positive violations produce more favorable outcomes than behavior that matches expectations, and negative violations produce more unfavorable outcomes than behavior that matches expectations.

Expectancies exert significant influence on people's interaction patterns, on their impressions of one another, and on the outcomes of their interactions. Violations of expectations in turn may arouse and distract their recipients, shifting greater attention to the violator and the meaning of the violation itself. People who can assume that they are well regarded by their audience are safer engaging in violations and more likely to profit from doing so than are those who are poorly regarded.[40] When the violation act is one that is likely to be ambiguous in its meaning or to carry multiple interpretations that are not uniformly positive or negative, then the reward valence of the communicator can be especially significant in moderating interpretations, evaluations, and subsequent outcomes. Violations have relatively consensual meanings and valences associated with them, so that engaging in them produces similar effects for positive and negative valenced communications.[40]

Metatheoretical Assumptions[edit]

Ontological Assumptions[edit]

EVT assumes that humans have a certain degree of free will. This theory assumes that humans can assess and interpret the relationship and liking between themselves and their conversational partner, and then make a decision whether or not to violate the expectations of the other person. The theory holds that this decision depends on what outcome they would like to achieve.[41] This assumption is based on the interaction position, the interaction position is based on a person's initial stance toward an interaction as determined by a blend of personal requirements, expectations, and desires (RED). These RED factors meld into our interaction position of what's needed, anticipated, and preferred.[41]

Epistemological Assumptions[edit]

EVT assumes that there are norms for all communication activities and if these norms are violated, there will be specific, predictable outcomes.[38] EVT does not fully account for the overwhelming prevalence of reciprocity that has been found in interpersonal interactions. Second, it is silent on whether communicator valence supersedes behavior valence or vice versa when the two are incongruent,such as when a disliked partner engages in a positive violation.[38]

Axiological Assumptions[edit]

This theory seeks to be value-neutral because the study was done empirically and seeks to objectively describe how humans react when their expectations are violated.[2]

Criticism of the theory[edit]

One critique of Expectation Violations Theory lies in the scope of thought and research devoted to the theory. A large amount of attention has been narrow in scope and has shown violations to be highly consequential acts, negative in nature, and uncertainty increasing. As Afifi and Metts (1998) point out, literature and anecdotal evidence illustrate that expectancy violations vary in frequency, seriousness, and valence. While it is true that many expectancy violations carry a negative valence, numerous are positive and actually reduce uncertainty because they provide additional information within the parameters of the particular relationship, context, and communicators.

Other critics of EVT believe most interaction between individuals is extremely complex and there are many contingency conditions to consider within the theory. This makes the prediction of behavioral outcomes of a particular situation virtually impossible.[16]

Emory Griffin, the author of A first look at communication theory, has analysed the Expectancy Violations Theory of Judee Burgoon.[42] His test consisted in analysing his interaction with four students who made various requests from him. The students' names have been changed to Andre, Belinda, Charlie and Dawn. They start with the letters A, B, C and D to represent the increasing distance between them and Griffin when making their requests.

Andre needed the author's endorsement for a graduate scholarship, and spoke to him from an intimate eyeball-to-eyeball distance. According to Burgoon's early model, Andre made a mistake when he crossed Griffin's threat threshold; the physical and psychological discomfort the lecturer might feel could have hurt his cause. However, later that day Griffin wrote the letter of recommendation.

Belinda needed help with a term paper for a class with another professor, and asked for it from a 2-foot distance. Just as Burgoon predicted, the narrow gap between Belinda and Griffin determined him to focus his attention on their rocky relationship, and her request was declined.

Charlie invited his lecturer to play water polo with other students, and he made the invitation from the right distance of 7 feet, just outside the range of interaction Griffin anticipated. However, his invitation was declined.

Dawn launched an invitation to Griffin to eat lunch together the next day, and she did this from across the room. According to the nonverbal expectancy violations model, launching an invitation from across the room would guarantee a poor response, but this time, the invitation was successful.

Griffin's attempt to apply Burgoon's original model to conversational distance between him and his students didn't meet with much success. The theoretical scoreboard read:

- Nonverbal expectancy violations model: 1

- Unpredicted random behavior: 3

Common expectancy violations in nonverbal communication[edit]

The Nonverbal Expectancy Violations Theory began to be developed in the late nineteen eighties by Judee K. Burgoon and her colleagues. The Nonverbal Expectancy Violations Theory "is based on five assumptions and contains five propositions".[43] These assumptions hold true regardless the culture involved, however the level of intensity given to each gesture varies. What could be thought of as a positive gesture in one culture, may be thought of as a negative in a different culture.

The first assumption according to Burgoon is that “humans have a competing approach and avoidance needs.” [44] This assumptions means that we have a need for people in our lives, whether it be people we already consider friends or those new ones that we invite into our circle of friends. On top of that, when our friends bring others into the picture we feel a need to make them accepted and welcome. However we do feel the competitive nature come into play to hackle them before allowing them into your friendship circle completely.

The second assumption in the Nonverbal Expectancy Violations Theory is that "communicators evaluate the reward potential of others" [44] This means, what is in it for you personally? People who come from an individualistic culture will view this second assumption through a lens of self-benefit. Those who come from a collectivist culture will view these benefits from a group perspective. As a society we want to do what will benefit us most as a person. This assumption shows that with every relationship we form we balance out the potential benefits that each relationship can bring us, and decide if the relationship is worthwhile.

The third assumption in the Nonverbal Expectancy Violations Theory is that "communicators develop expectations about the nonverbal behaviors of others".[44] Within each culture we have our own set of expectations that we tend to abide by. We can, more times than not, pick out how another person will react to any given situation, even without knowing them. This is based on the idea that each culture is brought up to recognize how people will react to different situations they may be faced with. Which in turn, also means that their expectation of behavior differ from culture to culture as well.

The fourth assumption in the Nonverbal Expectancy Violations Theory is "nonverbal behaviors have associated evaluations ranging from extremely positive to extremely negative".[44] When we look at and evaluate the nonverbal messages and cues of others we do it in a way that can generate a number of feelings with different intensities. One behavior may be interpreted by one person completely differently then another person. The more positive the emotion we feel the more likely we are to engage in conversation further and more in depth. If it is more of a negative feeling we tend to shut down more and do not engage in conversation as much as we normally would.

The fifth assumption in the Nonverbal Expectancy Violations Theory posits that "nonverbal behaviors have socially recognized meaning".[44] Within different cultures our nonverbal messages have universal meanings that everyone recognizes and interprets with relative similarity.

Proxemics and kinesics of expectancy violations theory[edit]

The next step of the Nonverbal Expectancy Violation model deals with the idea of Proxemics and Kinesics. This part of the theory explains the notion of “Personal space” and our reactions to other who seem to “violate” our sense of personal space.[45] What we define as personal space, however, varies from culture to culture, and person to person. The “success” or “failure” of violations are linked to perceived attraction, credibility, influence and involvement. The context and purpose of interaction are relevant, as are the communicator characteristics of gender, relationships, status, social class, ethnicity and culture.[45] When it comes to different interactions between people, what each person expects out of the interaction will influence their individual willingness to risk violation. If a person feels comfortable in a situation, they are more likely to risk violation, and in turn will be rewarded for it.

Introduced by Edward Hall in 1966, Proxemics deals with the amount of distance between people as they interact with one another.[46] Based on how close people are during interaction, can be an indication of what type of relationship the people involved have.

There are 4 different personal zones defined by Hall. These zones include:

- Intimate Space: (0-18 inches) - This distance is for close, intimate encounters. Normally core family, close friends, lovers, or pets. People will normally share a unique level of comfort from one another.[47]

- Personal Space: (18 inches – 4 feet) - Reserved for conversations with friends, extended family, associates, and group discussions. The personal space will give each person more space compared with the intimate distance, it is still close to each other so it could involve touching one another.[47]

- Social Space: (4–10 feet) - This space is reserved for newly formed groups, and new acquaintances and colleagues you may have just met. Within this section people generally do not engage physically with one another.[47]

- Public Space: (10 feet to infinity) - Reserved for a public setting with large audiences, strangers, speeches, and theaters.

Many different cultures are influenced by Proxemics in different ways and respond differently to the same situation. In some cultures they can greet each other with a kiss on the cheek which is close contact engagement with someone which is the intimate stage of proxemics. On the other hand some cultures prefer greeting each other with a handshake, which is some physical contact but also keeping space between each other which is shown as the personal level.[48] Across the Proxemic Zones the actions can be different across different cultures. For example in Japan, Japanese people address different people in different ways but addressing someone wrong in Japan can cause an expectancy violation. Japanese people do not address people by their first name unless they have been given permission, calling someone by their first name in Japan is seen as an insult. In the Japanese culture, they address people by using their last name and 'san', which is equivalent to 'Mr.','Mrs.' and 'Ms.' in the English language. The way Japanese people address each other is an example of a verbal Proxemic zone. For example, when the Japanese allow a person to call them by their first name is an example of intimate space, because only someone very close to them is allowed the privilege to address them this way.[49]

Common expectancy violations in close relationships[edit]

It is important to note that EVT can apply to both non-relational interaction and close relationships. In 1998, more than twenty years after the theory was first published, Afifi and Metts conducted several studies to catalog the types of expectancy violations commonly found in close relationships.[36] They asked people in friendships and romantic relationships to think about the last time their friend or partner did or said something unexpected. They emphasized that the unexpected event could be either positive or negative. Participants reported on events that had occurred, on average, five days earlier, suggesting that unexpected behaviors happen often in relationships. Some of the behaviors reported were relatively mundane, and others were quite serious. The outcome of the list was a list of nine general categories of expectation violations that commonly occur in relationships. [50]

- Support or confirmation is an act that provides social support in a particular time of need, such as sitting with a friend who is sick.

- Criticism or accusation is critical of the receiver and accuse the individual of an offense. These are violations because they are accusations not expected.

- Relationship intensification or escalation intensifies the commitment of the communicator. For instance, saying “I love you,” signifies a deepening of a romantic relationship.

- Relationship de-escalation does the opposite. An example might be spending more time apart.

- Relational transgressions are violations of the perceived rules of the relationship. Examples include having an affair, deception, or being disloyal.

- Acts of devotion are unexpected overtures that imply specialness in the relationship. Buying flowers for no particular occasion falls into this category.

- Acts of disregard show that the partner is unimportant.

- Gestures of inclusion are actions that show an unexpected interest in having the other included in special activities or life. Examples include invitations to spend a special holiday with someone or disclosure of personal information, or inviting the partner to meet one’s family.

- Uncharacteristic relational behavior is unexpected action that is not consistent with the partner’s perception of the relationship. A common example is one member of an opposite-sex friendship demanding a romantic relationship of the other.

Afifi and Metts later collapsed the support or confirmation category into acts of devotion and included another category, uncharacteristic social behavior. These are acts that aren’t relational but are unexpected, such as a quiet person raising his or her voice.[13]

The theory in new media age[edit]

As new media technology developing, people have more choices of receiving and sharing information. Since EVT focuses more on the nonverbal communication process, how does it be applied to new media age can be an interesting issue.

The popularity of computer-mediated communication (CMC) as means of conducting task-oriented and socially oriented interactions is evidenced in its ability to fulfill many of the same functions as other more traditional forms of interaction, especially face-to-face (FtF) interaction.[51] Participants evaluated the social information more positively and uncertainty-reducing following short-term online associations but more negatively and uncertainty-provoking following long-term ones compared to remaining online.[52]

In social media like Facebook, people are connected with friends and sometimes strangers. In this case, the expectancy violation can be conducted by different behaviors between strong ties and weak ties. An expectancy violation is defined as an incongruity between a profile's intended audience and its expected audience.[53] Norms violation on Facebook can include too many status updates, overly emotional status updates or Wall posts, heated interactions, fights, and name calling through Facebook’s public features and being tagged on posts or pictures that might reflect negatively on an individual.[54] A 2008 study of the top 500 US colleges by Kaplan found that 10% of admissions offices checked applicants’ SNS profiles, and 38% of those saw information that negatively impacted the applicants’ prospects for admission (Hechinger, 2008). [55] Recently, a college student was cited for underage drinking after campus police found pictures on Facebook of student holding a beer.[56] Unlike FtF communication, CMC allows people to pretend to be connected with person who violate their expectancy by ignoring violations or filterring news feed. Meanwhile, people can also cut the connection completely with someone who is not important by deleting friends when serious violation occurs. A confrontation is much more likely for close friends than for acquaintances, and compensation is much more likely for acquaintances, a finding in contrast to the typical EVT predictions.[54] Also, EVT on the Internet environment is strongly related to online privacy issue.

Related theories[edit]

As mentioned above, EVT has strong roots in Uncertainty Reduction Theory. The relationship between violation behavior and the level of uncertainty is under study. A research does indicates that violations differ in their impact on uncertainty. To be more specific, incongruent negative violations heightened uncertainty, whereas congruent violations (both positive and negative) caused declines in uncertainty.[57] The theory also borrows from Social Exchange Theory in that people seek reward out of interaction with others. Two other theories share similar outlooks to EVT – Discrepancy-Arousal Theory and Patterson’s Social Facilitation Model. Like EVT, DAT explains that a receiver becomes aroused when a communicative behavior does not match the receiver’s expectations. In DAT, these differences are called discrepancies instead of expectancy violations. Cognitive Dissonance and EVT both try to explain why and how people react to unexpected information and adjust themselves during communication process. Social Facilitation Model has a similar outlook and labels these differences as unstable changes. A key difference between the theories lies in the receiver’s arousal level. Both DAT and SFM maintain that the receiver experiences a physiological response whereas EVT focuses on the attention shift of the receiver. EVT posits that expectancy violations occur frequently and are not always as serious as perceived through the lenses of other theories. Anxiety/Uncertainty Management Theory is the uncertainty and Anxiety people have towards each other, relating to EVT this anxiety and uncertainty can differ between cultures. Causing a violation for example violating someones personal space or communicating ineffectively can cause uncertainty and anxiety.[58]

Criticism of the theory[edit]

One critique of Expectation Violations Theory lies in the scope of thought and research devoted to the theory. A large amount of attention has been narrow in scope and has shown violations to be highly consequential acts, negative in nature, and uncertainty increasing. As Afifi and Metts (1998) point out, literature and anecdotal evidence illustrate that expectancy violations vary in frequency, seriousness, and valence. While it is true that many expectancy violations carry a negative valence, numerous are positive and actually reduce uncertainty because they provide additional information within the parameters of the particular relationship, context, and communicators.

Other critics of EVT believe most interaction between individuals is extremely complex and there are many contingency conditions to consider within the theory. This makes the prediction of behavioral outcomes of a particular situation virtually impossible.[16]

Further use and development of the theory[edit]

The concept of Social Norms Marketing follows expectancy violation in that it is based upon the notion that messages containing facts that vary from perception of the norm will create a positive expectancy violation. Advertising, strategic communications, and public relations base social norms campaigns on this position.[59]

Interaction Adaptation Theory further explores expectancy violations. Developed by Burgoon to take a more comprehensive look at social interaction, IAT posits that people enter into interactions with requirements, expectations, and desires. These factors influence both the initial behavior as well as the response behavior. When faced with behavior that meets an individual’s needs, expectations, or desires, the response behavior will be positive. When faced with behavior that does not meet an individual’s needs, expectations, or desires, he or she can respond either positively or negatively depending on the degree of violation and positive or negative valence of the relationship.[60][61]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Burgoon, Judee (1976). "Toward a Theory of Personal Space Expectations and Their Violations". Human Communication Research. 2 (2): 131–146. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.1976.tb00706.x.

- ^ a b c d Burgoon, J. K. (1978). "A Communication Model of Personal Space Violations: Explication and an Initial Test". Human Communication Research. 4 (2): 130–131. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.1978.tb00603.x. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ Burgoon, J.K. (1983). Nonverbal Violations of Expectations: In J.M. Wiemann & R.R. Harrison (Eds.), Nonverbal Interaction, (pp. 11-77). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- ^ a b Burgoon, J. K. & Hale, J. L. (1988). Nonverbal Expectancy Violations: Model Elaboration and Application to Immediacy Behaviors. Communication Monographs, 55, 58-79.

- ^ Burgoon, J. K. & Jones, S. B. (1976). Toward a Theory of Personal Space Expectations and Their Violations. Human Communication Research, 2, 131-146.

- ^ McPherson, M. B., & Yuhua, J. L. (2007). Students’ Reactions to Teachers’ Management of Compulsive Communicators. Communication Education, 56, 18-33.

- ^ "Griffin 2012" Griffin, EM. A First Look at Communication Theory.

- ^ Beth A. Le Poire & Stephen M. Yoshimura (1999): The effects of expectancies and actual communication on nonverbal adaptation and communication outcomes: A test of interaction adaptation theory, Communication Monographs, 66:1, 1-30

- ^ Floyd, K. & Voloudakis, M. (1999). Affectionate Behavior in Adult Platonic Friendships: Interpreting and Evaluating Expectancy Violations. Human Communication Research, 25, 341-369.

- ^ Griffin, Em (2012). A first look at communication theory (8th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 84. ISBN 9780073534305.

- ^ Burgoon, Judee K (1988). "Nonverbal expectancy violations and conversational involvement". Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. 13 (2): 97–119. doi:10.1007/BF00990793. S2CID 144144792.

- ^ Afifi, Walid (2011). violations theory&pg=PA92 Close Encounters: Communication in Relationships. Sage Publication. pp. 90–91. ISBN 9781412977371.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ a b Guerrero, L. K., Andersen, P. A., & Afifi, W. A. (2001). Close Encounters: Communicating Relationships. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ^ Eadie, edited by William F. (2009). 21st century communication : a reference handbook. Los Angeles: Sage. ISBN 9781412950305.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Technology, Teri Kwal Gamble, College of New Rochelle & Michael W. Gamble, New York Institute of (2014). Interpersonal communication : building connections together (PDF). Thousand Oaks, Calif: SAGE Publications. pp. 1–34. ISBN 9781452220130.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Miller, K. (2005). Communication Theories: Perspectives, Processes, and Contexts. NewYork: McGraw Hill.

- ^ Ledbetter, Em Griffin ; special consultants Glenn G. Sparks, Andrew M. (2011). First look at communication theory (8. ed.). [S.l.]: Mcgraw Hill Higher Educat. pp. 89–90. ISBN 9780071086424.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ledbetter, Em Griffin ; special consultants Glenn G. Sparks, Andrew M. (2011). First look at communication theory (8. ed.). [S.l.]: Mcgraw Hill Higher Educat. p. 84. ISBN 9780071086424.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ifert Johnson, Danette; Nicole Lewis. "Perceptions of Swearing in the Work Setting: An Expectancy Violations Theory Perspective". Communication Reports. 23 (2): 107.

- ^ Snyder, Mark; Arthur A. Stukas, Jr. (1999). "INTERPERSONAL PROCESSES: The Interplay of Cognitive, Motivational, and Behavioural activities in Social Interaction". Annu Rev Psychol. 50: 273–303. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.273. PMID 10074680.

- ^ K. Sebenius, James (December 2009). "Assess, don't assume part 1 : Etiquette and national culture in negotiation".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Ledbetter, Em Griffin ; special consultants Glenn G. Sparks, Andrew M. (2011). First look at communication theory (8. ed.). [S.l.]: Mcgraw Hill Higher Educat. p. 91. ISBN 9780071086424.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zelley, Marianne Dainton, Elaine (2011). Applying communicationtheory for professional life : a practical introduction (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, Calif.: SAGE Publications. p. 48. ISBN 978-1412976916.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ledbetter, Em Griffin ; special consultants Glenn G. Sparks, Andrew M. (2011). First look at communication theory (8. ed.). [S.l.]: Mcgraw Hill Higher Educat. p. 90. ISBN 9780071086424.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zelley, Marianne Dainton, Elaine (2011). Applying communication theory for professional life : a practical introduction (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, Calif.: SAGE Publications. p. 48. ISBN 978-1412976916.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f M. Dainton; E. D. Zelley (2010). Applying Communication Theory for Professional Life: A Practical Introduction (2 ed.). Sage Publications, Inc. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-1412976916.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k E. Griffin (2012). "Chapter 7: Expectancy Violations Theory". A First Look at Communication Theory (8 ed.). The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. pp. 84–92. ISBN 978-0-07-353430-5.

- ^ a b c d e Hall, E. T. (1966). The Hidden Dimension. United States of America: Anchor Books. pp. 113–125. ISBN 978-0385084765.

- ^ Altman, I. (1975). Environment and social behavior: Privacy, personal space, territory, and crowding. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole Publishing Company.

- ^ M. L. Knapp; J. A. Hall (2005). "The Communication Environment". Nonverbal Communication in Human Interaction (6th ed.). Wadsworth Publishing Company, Inc. p. 124. ISBN 978-0534625634.

- ^ a b c M. L. Houser (2005). "Are We Violating Their Expectations? Instructor Communication Expectations of Traditional and Nontraditional Students". Communication Quarterly. 53 (2). Taylor & Francis Online: 217–218. doi:10.1080/01463370500090332. S2CID 143959947. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- ^ a b c Burgoon, J. K.; S. B. Jones (1976). "Toward a Theory of Personal Space Expectations and Their Violations". Human Communication Research. 2 (2): 131–146. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.1976.tb00706.x.

- ^ a b c L. K. Guerrero (2011). "Making Sense of Our World". Close Encounters: Communication in Relationships (3rd ed.). United States of America: Sage Publications, Inc. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-4129-7737-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ West, R. L.; L. H. Turner (2007). Introducing Communication Theory: Analysis and Application (3rd ed.). The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. p. 188. ISBN 9780073135618.

- ^ Le Poire B. A. & Burgoon J. K. (1996). Usefulness of Differentiating Arousal Responses within Communication Theories: Orienting Responses or Defensive Arousal within Nonverbal Theories of Expectancy Violation. Communication Monographs, Volume 63, September 1996

- ^ a b c Afifi, W. A., & Metts, S. (1998). Characteristics and Consequences of Expectation Violations in Close Relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 15, 365-392.

- ^ Houser, M. L. (2005). Are We Violating Their Expectations? Instructor Communication Expectations of Traditional and Non Traditional Students. Communication Quarterly, 53, 213-228.

- ^ a b c Guerrero, L. K. and Burgoon, J. K. (1996), Attachment Styles and Reactions to Nonverbal Involvement Change in Romantic Dyads Patterns of Reciprocity and Compensation. Human Communication Research, 22: 335–370.

- ^ Burgoon, J. K., Stern L. A., & Dillman, L. (1995). Interpersonal adaptation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b Burgoon, Judee K.; Coker, Deborah A.; Coker, RAY A. (1986). "Communicative Effects of Gaze Behavior". Human Communication Research. 12 (4): 495–524. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.1986.tb00089.x.

- ^ a b Burgoon, J. K.; White, C. H. (2001). "Adaptation and communicative design". Human Communication Research. 27 (1): 9–37. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.2001.tb00774.x.

- ^ Griffin, Emory A (2012). A first look at communication theory. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 84–87. ISBN 978-0-07-353430-5.

- ^ Gudykunst, W. and Kim, Y. (2003). Communicating with strangers: An approach to intercultural communication. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill

- ^ a b c d e Burgoon, Judee (1992). Applying a comparative approach to nonverbal expectancy violations theory. Sage. pp. 53–69.

- ^ a b Burgoon, J. (1989). Nonverbal communication. New York: Harper&Row.

- ^ a b Hall, Edward (1966). The Hidden Dimension. Anchor Books. ISBN 0-385-08476-5.

- ^ a b c http://proxemics.weebly.com/types-of-proxemics.html

- ^ http://proxemics.weebly.com/proxemics-and-culture.html

- ^ http://maki.typepad.com/justhungry/2009/08/when-to-use-chan-or-san-and-other-ways-to-address-people-in-japan-.html

- ^ Afifi, Walid (2011). Close Encounters: Communication in Relationships. Sage Publication. p. 93. ISBN 9781412977371.

- ^ Walther, J. B., & Parks, M. R. (2002). Cues filtered out, cues filtered in: Computer-mediated communication and relationships. In M. L. Knapp & J. A. Daly (Eds.), Handbook of interpersonal communication (3rd ed., pp. 529–563). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- ^ Ramirez, A. Jr. & Wang, Z. M. (2008). When Online Meets Offline: An Expectancy Violations Theory Perspective on Modality Switching. Journal of Communication 58 (2008) 20–39. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2007.00372.x

- ^ Stutzman F. & Kramer-Duffield J. (2010). Friends Only: Examining a Privacy-Enhancing Behavior in Facebook. CHI 2010, April 10–15, 2010, Atlanta, Georgia, USA. Copyright 2010 ACM 978-1-60558-929-9/10/04.

- ^ a b McLaughlin C. & Vitak J. (2011). Norm evolution and violation on Facebook. New Media Society 2012 14: 299 originally published online 26 September 2011 doi:10.1177/1461444811412712

- ^ Hechinger J (2008) College applicants, beware: Your Facebook page is showing. Wall Street Journal, 18 September. Available at: http://online.wsj.com/McLaughlin, Caitlin; Jessica Vitak (26 September 2011). "Norm evolution and violation on Facebook". 14 (2): 299–300. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) article/SB122170459104151023.html (accessed 3 December 2009) - ^ McLaughlin, Caitlin; Jessica Vitak (26 September 2011). "Norm evolution and violation on Facebook". 14 (2): 299–300. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Afifi W. A. & Burgoon J. K. (2000). The Impact of Violations on Uncertainty and the Consequences for Attractiveness. Human Communication Research, Vol. 26 No. 2, April 2000 203–233

- ^ Griffin, Em (2012). A first look at communication theory (8th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ^ Campo, S., Cameron, K. A., Brossard, D., & Frazer. M. S. (2004). Social Norms and Expectancy Violation Theories: Assessing the Effectiveness of Health Communication Campaigns. Communication Monographs, 71, 448-470.

- ^ Floyd, K. & Ray, G. (2005). Adaptation to Expressed Liking and Disliking in Initial Interactions: Nonverbal Involvement and Pleasantness Response Patterns. Conference Papers -- International Communication Association Annual Meeting, 1-39.

- ^ Burgoon, J. K., Le Poire, B. A., & Rosenthal, R. (1995). Effects of Preinteraction Expectancies and Target Communication on Perceiver Reciprocity and Compensation in Dyadic Interaction. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 31, 287-321.

Category:Interpersonal communication Category:Communication theory