User:Beatrizsborges/sandbox

Les puits des houillères de Ronchamp are a series of collieries undertaken by the various mining companies in the Ronchamp coalfield between the early 19th and mid-20th centuries at Ronchamp, Champagney and Magny-Danigon, in the Haute-Saône département of France.

This article provides an annotated list of these twenty-seven wells, as described in the main article on Ronchamp coal mines.

From 1760 to 1810, coal was extracted by galleries and bures. From 1810 to 1900, twenty-six increasingly deep shafts were dug. In 1950, the twenty-seventh was dug in the Etançon forest. Two of these belonged to the independent Mourière concession, which exploited a geologically different deposit from the one at Ronchamp. The Société civile des houillères de Ronchamp (SCHR) dug France's deepest shaft twice in succession: the Magny shaft (694 meters) in 1878 and the Arthur-de-Buyer shaft (1,010 meters) in 1900. Each of the twenty-seven wells has its history and characteristics. Their lifespan is highly variable: those encountering terrain accidents or technical difficulties are abandoned just a few years after they are sunk, while wells encountering significant layers can last several decades, but usually with irregular operation, alternating between periods of activity and mothballing.

Contexte[edit]

The Ronchamp coalfields were officially discovered in the mid-18th century in the woods above the villages of Ronchamp and Champagney. Two concessions were granted in 1757: that of the Lords of Ronchamp for the commune of Ronchamp, and that of the Prince-Abbots of Lure for Champagney. These were subsequently merged to form a single concession in 1763.

Another concession was granted in 1766 to the Prince of Bauffremont at Mourière, a hamlet to the northwest of the coalfield. However, he did not exploit the coal, and it was not until 1844 that Monsieur Grézely fils, in partnership with Messieurs Conrad et consorts, began mining coal, which he continued until 1891, after a change of ownership in 1872. The Ronchamp coalfields were booming at the time, and a large number of wells were dug, deeper and deeper towards the south. This was because the deposit, which is shaped like a ship's hull, is inclined in that direction.

The Compagnie des maîtres de forge was founded in 1847, and in 1862 obtained a concession to the south of the Ronchamp mining concession. But both companies had spent a lot of money to obtain the Éboulet concession, and were forced to merge in 1866. In 1919, the société civile des houillères de Ronchamp changed its legal form to become a société anonyme. When the French coal industry was nationalized in 1946, Électricité de France (EDF) became the owner of the mine until the last shaft was closed in 1958. The concession was relinquished in 1961.

The various shafts sunk in the coalfield are increasingly deep due to the inclined slope of the coal beds. Each new shaft therefore requires larger and more complex infrastructure than its predecessors, not only to overcome the problems caused by extracting coal at great depths (particularly dewatering and ventilation), but also to improve yields and offer miners better working conditions (less danger, mechanized tools, etc.).

Most shafts are used for coal extraction, but they can also be used for other purposes such as ventilation, dewatering, research or service (lowering of equipment and personnel, emergency exit).

Life of the 27 shafts[edit]

The shafts are colored according to their respective concessions: darker shades indicate periods of coal extraction, lighter shades indicate other functions or mothballing.

Saint-Louis shaft[edit]

47°42′25″N 6°39′13″E / 47.706895°N 6.653493°E

The Saint-Louis shaft was the first true mine shaft sunk in the coalfield, south of the hamlet of La Houillère. It was the most productive shaft of the first half of the 19th century. The shaft was also the site of the basin's first firedamp explosion, on April 10, 1824, which killed twenty people and injured sixteen others. Later, on May 31, 1830, a second and even more deadly firedamp explosion claimed twenty-eight victims. The pit was finally abandoned and backfilled in 1842.[1][2][3]

After closure, one of the buildings was preserved as a casino and ballroom, before being demolished in the 1960s.[4] At the beginning of the 21st century, almost no trace of the installations remains, and the shaft is located under a pavilion at the foot of a hill.[5] A decorative monument built in 2012 recalls the site's mining past.[6]

-

View of the Saint-Louis shaft, dated 1826.

-

The site of the Saint-Louis shaft.

-

The monument built on the site of the well.

-

Small outbuilding in ruins.

Henri IV shaft[edit]

47°42′32″N 6°39′15″E / 47.708993°N 6.654105°E

Shaft sinking began in 1815. In October 1816, it reached the first layer at a depth of 21 metres and a thickness of 1.30 metres. It is used to draw water from the lower workings and discharge it at the level of the large drainage channel; the water is removed from the galleries by hand pumps and then brought to light by ox-driven pumps. These pumps operate at a rate of twelve to fifteen pulses per minute, with a flow rate of 1.5 liters per piston stroke.[7] Finally, other hand pumps were used to convey water to the gully.[8]

On May 12, 1823, he crossed the second layer some twenty metres below the first. This layer is 1.6 metres thick, including 0.3 metres of sterile rock. It is mined by the Cantine and Carrière galleries, despite a limited mining area.[9]

On June 15, 1830, the Henri IV shaft reached a depth of 61 meters. It serves as an air return for the Saint-Louis shaft. In 1830, production at the latter was 7,200 tons, with a workforce of 35 miners and 29 laborers.[10]

In 1833, just as the second layer was about to be exhausted at the Henri IV and Saint-Antoine wells,[11] a third vein (a schistose and pyritic vein), 1.80 metres thick, was encountered and mined. Work was finally abandoned in 1835. During the Etançon disaster in December 1950, this shaft and the Petit-Pierre shaft reopened under water pressure. A plum tree was completely swallowed up in the hole formed by the Henri IV well. Both shafts were backfilled with shalek/.[12][13]

At the beginning of the 21st century, the well was located in the courtyard of a house.[14]

Samson shaft[edit]

47°42′29″N 6°38′47″E / 47.708116°N 6.64646°E

The location of the shaft was chosen to the west of the Basvent gallery (located in the hamlet of La Houillère) and 140 metres south-west of the orifice of the large drainage channel.[15][16] Sinking of the shaft began on October 1, 1822 in the Etançon valley. It was stopped at a depth of 17 metres due to a heavy influx of water, requiring 225 to 250 60-litre water skips to be hauled up every 24 hours, representing a flow rate of 13.8 m3 per day.[17] The well is 3.6 meters long and 1.6 meters wide, and is equipped with ladders. When abandoned, the well cost 200 francs per meter dug. Sinking resumed in April 1824 and the first layer was reached at 18.66 meters. The shaft was stopped at a depth of 19 metres and abandoned the same year due to the poor quality of the coal and the influx of water.[17][18] In fact, the shaft fell on an uplift in the ground that compressed the two layers of coal to the point of bringing them almost into contact and flattening them.[9]

At the beginning of the 20th century, the well site was invaded by the Fourchie pond, fed by the large drainage channel. A house built on the site was also invaded, but later destroyed by fire in the 1930s. The ruins remained until the 1970s.[19] In 1952, the Samson shaft (a gallery built from the surface) was dug not far from the old well, bypassing the old drowned workings. At the beginning of the 21st century, the shaft was located in a swamp not far from the outcrop mining circuit.[20]

-

The pit site, invaded by Fourchie pond.

-

Fourchie pond.

-

Swampy area where the Samson well is located.

-

The sign indicating the Samson well.

Shaft no. 1[edit]

47°42′28″N 6°40′13″E / 47.707906°N 6.670284°E

Sinking of the shaft began in June 1825 at “La Bouverie”, at the foot of the Chevanel wood, which had long been mined by drifting. Digging was subcontracted to the d'Andlau[21] company, with the workers supplying the powder and oil.[22] The upper section is lined with a 15-meter-high casing. The average depth is 6 meters per month. The workers are also responsible for tool maintenance and frame installation. At a depth of 149 metres, they encounter a 2.25-metre vein encased in a 0.35-metre layer of sandstone. A 12-horsepower steam engine is installed for extraction. The coal is transported in 400 kg Anzin-model carts on a rail track.[22]

Between 1828 and 1830, production at the shaft rose from 6,000 to 12,000 tonnes a year, and the workforce grew from 36 miners and 40 labourers to 64 miners and 54 labourers.[10]

In 1831, the waggons were loaded onto trays and brought to daylight. It was at this time that an extraction cage was first used in a shaft at the Ronchamp mines. In the same year, the shaft was deepened by 24 meters and a 320-meter-long research gallery was sunk to the east, but to no avail. In 1833, the strangulation of the coal seams put an end to mining.[12][23]

At the beginning of the 21st century, the shaft was a four-meter-diameter water hole at the edge of the Paris-Basel railway line.[24]

-

Plan of well installations.

-

Remains of shaft no. 1.

-

Remains of fence around the well.

Shaft no. 2[edit]

47°42′19″N 6°39′45″E / 47.705328°N 6.662416°E

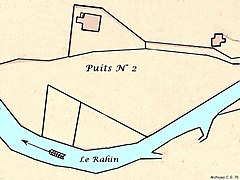

The shaft was sunk in June 1825 towards the Rahin river, and received a casing with a picot casingNote 1 over 21 meters.[23] At a depth of 116 meters, it encountered carbonaceous schists. Some reconnaissance work was carried out, with little result. The cuttings were hauled up by a horse-drawn baritel, later replaced by the steam engine at the Saint-Louis shaft. Shaft digging was stopped at a depth of 126.6 metres.[23]

In November 1828, a 120-meter-long research gallery was dug in the up-dip area, but to no avail. In November 1829, a travers-banc in the down-dip part of the work was equally unproductive. Later, in a westerly direction, a number of cuttings were installed. Between 1828 and 1830, production at the shaft rose from 0 to 180 tonnes a year, and the workforce increased from 8 miners and 4 labourers to 12 miners and 10 labourers.[10] In 1833, research was carried out, but proved unsuccessful, showing that the shaft had been dug on an uplift in the coalfield. It was decided to abandon the shaft.[25] The installation of a 70 hp steam engine, initially envisaged, was cancelled due to excessive costs.[9]

At the beginning of the 21st century, the well site was located at the foot of the hills overlooking the communes of Ronchamp and Champagney.[26]

-

Plan of the well facilities towards Rahin.

-

Hill overlooking the site of Shaft No. 2.

Shaft no. 3[edit]

47°42′47″N 6°39′46″E / 47.713041°N 6.662915°E

Sinking of shaft no. 3 began at the end of 1825, north of the large drainage channel,[27] in ground where there was still a lot of coal. It reached a depth of 38.5 meters[25] and tapped the upper part of the Galerie du Cheval, as well as the downstream parts of the Grande Rigole. It is served by a horse-drawn arena. The area is notoriously unstable, with dozens of mine quarters collapsing between 1811 and 1813.[27] Shaft no. 3 was abandoned in August 1828[28] after producing 9,000 tons of coal with a workforce of 54 miners and 60 laborers.[10]

-

Remains of shaft no. 3.

-

The remains of the slag heap.

Shaft no. 4[edit]

Sinking of the shaft began in April 1829 on the advice of a master miner 90 metres south of shaft no. 3,[27] in an area where a 1,700 m3 panelNote 2 existed between the eastern part of the Cheval works and the large drainage channel.[29] In 1830, the shaft produced 2,880 tons of coal with a workforce of 8 miners and 60 laborers.[10] Served by a baritel, it was backfilled around 1840.[12]

At the beginning of the 21st century, shaft no. 4 was a small funnel-shaped subsidence in the forest close to a road.[30]

-

Funnel-shaped hole, remnant of shaft no. 4.

-

The slag heap at shaft no. 4.

-

The old track linking Shaft No. 4 and Shaft No. 3.

Shaft no. 5[edit]

Sinking of the shaft began on May 20, 1830, on the advice of Mr. Thirria, engineer from Vesoul, who had planned to sink the shaft 1,200 meters south of shaft no. 1 (not far from the future Sainte-Pauline and Sainte-Barbe shafts), but the mining company decided to sink it only 800 meters from the latterM 9. The shaft is rectangular in cross-section, measuring 2.75 x 2.26 metres, with three compartments: one for extraction (2.26 x 1.54 metres), one for ladders (2.26 x 0.8 metres) and one for ventilation (2.26 x 0.4 metres)M 3. The first casing kit is installed at a depth of nine metresM 10.

In March 1831, the casing was extended to a depth of 31 metres with a spiked casingNote 1, and in October the shaft reached a depth of 52 metres. At the end of 1831, sinking of shaft no. 5 was suspended due to lack of fundingM 10. Sinking was finally resumed in March 1832, only to stop again in May 1832 at a depth of 36.8 metres to drill a hole at the bottom of the shaft, which reached 50 metres on July 5. At 130 meters from the surface, he encountered coal-bearing soil, but no trace of coal. This shallow depth suggested a ground uplift. No coal was extracted and the shaft was abandonedA 1,M 10.

At the beginning of the 21st century, the well is a water hole in the Époissesi 9 wood.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Parietti (2001, p. 14)

- ^ Parietti (2001, p. 52)

- ^ Parietti (2001, p. 14)

- ^ "Le bâtiment annexe du Casino". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-22.

- ^ "Le puits Saint Louis". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-22.

- ^ "Ronchamp. Le bassin houiller refait surface". www.estrepublicain.fr (in French). Retrieved 2024-05-22.

- ^ Mathet (1881, p. 107)

- ^ "La grande rigole d'écoulement". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-22.

- ^ a b c Trautmann (2014, p. 35)

- ^ a b c d e Michel Godard (2012, p. 91)

- ^ Trautmann (2014, p. 34)

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

:0was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Les tragédies de la mine de Ronchamp". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-23.

- ^ "Le puits numero 1". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-23.

- ^ "La grande rigole d'écoulement". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-23.

- ^ Trautmann (2014, p. 28)

- ^ a b Mathet (1881, p. 111)

- ^ Mathet (1881, p. 131)

- ^ "Le plan de l'étang Fourchie à l'Etançon". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-23.

- ^ "Le sentier des affleurements de charbon". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-23.

- ^ Michel Godard (2012, p. 736)

- ^ a b Mathet (1881, p. 117)

- ^ a b c Mathet (1881, p. 118)

- ^ "Le puits numero 1". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-23.

- ^ a b Mathet (1881, p. 119)

- ^ "Le puits numero 2". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-23.

- ^ a b c Trautmann (2014, p. 29)

- ^ Mathet (1881, p. 120)

- ^ Mathet (1881, p. 122)

- ^ "Le puits numero 4". www.abamm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-22.