Bedaquiline

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Sirturo |

| Other names | Bedaquiline fumarate,[1] TMC207,[2] R207910, AIDS222089 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a613022 |

| License data |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | >99.9%[6] |

| Metabolism | Liver, by CYP3A4[7] |

| Elimination half-life | 5.5 months[7] |

| Excretion | fecal[7] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

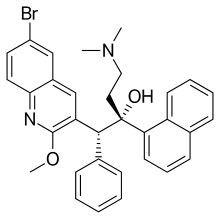

| Formula | C32H31BrN2O2 |

| Molar mass | 555.516 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Bedaquiline, sold under the brand name Sirturo, is a medication used for the treatment of active tuberculosis.[1] Specifically, it is used to treat multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis along with other medications for tuberculosis.[1][8][9] It is taken by mouth.[3]

Common side effects include nausea, joint pains, headaches, and chest pain.[1] Serious side effects include QT prolongation, liver dysfunction, and an increased risk of death.[1] While harm during pregnancy has not been found, it has not been well studied in this population.[10] It is in the diarylquinoline antimycobacterial class of medications.[1] It works by blocking the ability of M. tuberculosis to make adenosine 5'-triphosphate (ATP).[1]

Bedaquiline was approved for medical use in the United States in 2012.[1] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[11]

Medical uses

[edit]Its use was approved in December 2012 by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in tuberculosis (TB) treatment, as part of a fast-track accelerated approval, for use only in cases of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, and the more resistant extensively drug resistant tuberculosis.[12]

As of 2013[update], both the World Health Organization (WHO) and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend (provisionally) that bedaquiline be reserved for people with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis when an otherwise recommended regimen cannot be designed.[13][14][needs update]

Side effects

[edit]The most common side effects of bedaquiline in studies were nausea, joint and chest pain, and headache. The drug also has a black-box warning for increased risk of death and arrhythmias, as it may prolong the QT interval by blocking the hERG channel.[15] Everyone on bedaquiline should have monitoring with a baseline and repeated ECGs.[3] If a person has a QTcF of > 500 ms or a significant ventricular arrhythmia, bedaquiline and other QT prolonging drugs should be stopped.[citation needed]

There is considerable controversy over the approval for the drug, as one of the largest studies to date had more deaths in the group receiving bedaquiline that those receiving placebo.[16] Ten deaths occurred in the bedaquiline group out of 79, while two occurred in the placebo group, out of 81.[17] Of the 10 deaths on bedaquiline, one was due to a motor vehicle accident, five were judged as due to progression of the underlying tuberculosis and three were well after the person had stopped receiving bedaquiline.[16] However, there is still significant concern for the higher mortality in people treated with bedaquiline, leading to the recommendation to limit its use to situations where a four drug regimen cannot otherwise be constructed, limit use with other medications that prolong the QT interval, and the placement of a prominent black box warning.[16][18]

Drug interactions

[edit]Bedaquiline should not be co-administered with other drugs that are strong inducers or inhibitors of CYP3A4, the liver enzyme responsible for oxidative metabolism of the drug.[3] Co-administration with rifampin, a strong CYP3A4 inducer, results in a 52% decrease in the AUC of the drug. This reduces the exposure of the body to the drug and decreases the antibacterial effect. Co-administration with ketoconazole, a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor, results in a 22% increase in the AUC, and potentially an increase in the rate of adverse effects experienced.[3]

Mechanism of action

[edit]Bedaquiline blocks the proton pump for ATP synthase of mycobacteria.[19] It is the first member of a class of drugs called the diarylquinolines.[19] Bedaquiline is bactericidal.[19] ATP production is required for cellular energy production and its loss leads inhibition of mycobacterial growth within hours of the addition of bedaquiline.[20] The onset of bedaquiline-induced mycobacterial cell death does not occur until several days after treatment, but nonetheless kills consistently thereafter.[20]

Resistance

[edit]The specific part of ATP synthase affected by bedaquiline is subunit c which is encoded by the gene atpE. Mutations in atpE can lead to resistance. Mutations in drug efflux pumps have also been linked to resistance.[21]

History

[edit]Bedaquiline was described for the first time in 2004 at the Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy (ICAAC) meeting, after the drug had been in development for over seven years.[22] It was discovered by a team led by Koen Andries at Janssen Pharmaceutica.[23]

Bedaquiline was approved for medical use in the United States in 2012.[1]

It is manufactured by Johnson & Johnson (J&J), who sought accelerated approval of the drug, a type of temporary approval for diseases lacking other viable treatment options.[24] By gaining approval for a drug that treats a neglected disease, J&J is now able to request expedited FDA review of a future drug.[25]

When it was approved by the FDA in December 2012, it was the first new medicine for TB in more than forty years.[26][27]

In 2016, the WHO came under criticism for recommending it as an essential medicine.[28]

The WHO TB program director has pointed out that Janssen will donate $30 million worth (30,000 treatment courses) of bedaquiline over a four-year period.[29]

In 2023, a request to extend the patent on bedaquiline until 2027, was rejected by the Indian patent office.[30] The patent was supposed to expire in July 2023, but J&J's "evergreening" practices will not allow the distribution of generics in several countries heavily afflicted by tuberculosis.[31]

In July 2023, the WHO's Stop TB program and Johnson & Johnson came to an agreement allowing for Stop TB Partnership's Global Drug Facility to produce generic bedaquiline for the majority of low and middle income countries.[32]

In July 2024, the Indian Patent Office’s rejected Johnson & Johnson's application for a pediatric version of bedaquiline, paving the way for more affordable generic alternatives, potentially reducing treatment costs by 80% beyond the primary patent’s expiration in July 2023.[33]

Society and culture

[edit]Economics

[edit]The cost for six months is approximately US$900 in low-income countries, $3,000 in middle-income countries, and $30,000 in high-income countries.[34]

The public sector invested $455–747 million in developing bedaquiline. This is thought to be 1.6x to 5.1x what the owner, Janssen Biotech, invested (estimated at $90–240 million). If capitalized and risk-adjusted, these costs become $647–1,201 million and $292–772 million, respectively.[35]

Research

[edit]In vitro experiments have indicated that bedaquiline may also target the mitochondrial ATP synthase of malignant mammalian cells and reduce the rate of metastasis.[36]

Bedaquiline has been studied in phase IIb studies for the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis while phase III studies are currently underway.[18] It has been shown to improve cure rates of smear-positive multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, though with some concern for increased rates of death.[17]

Small studies have also examined its use as salvage therapy for non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections.[18]

It is a component of the experimental BPaMZ combination treatment (bedaquiline + pretomanid + moxifloxacin + pyrazinamide).[37][38]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Bedaquiline Fumarate". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ Diacon AH, Pym A, Grobusch M, Patientia R, Rustomjee R, Page-Shipp L, et al. (June 2009). "The diarylquinoline TMC207 for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 360 (23): 2397–405. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0808427. PMID 19494215.

- ^ a b c d e "Sirturo- bedaquiline fumarate tablet". DailyMed. 17 October 2023. Archived from the original on 19 April 2024. Retrieved 20 April 2024.

- ^ "Sirturo EPAR". European Medicines Agency. 26 August 2005. Archived from the original on 18 March 2024. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ "Sirturo Product information". Union Register of medicinal products. 7 March 2014. Archived from the original on 18 March 2024. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ "Sirturo: Clinical Pharmacology". Archived from the original on 28 February 2015. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ^ a b c "Bedaquiline". Archived from the original on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ^ "WHO Rapid Communication: Key changes to treatment of multidrug- and rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis (MDR/RR-TB)". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 20 August 2018. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- ^ Ahmad N, Ahuja SD, Akkerman OW, Alffenaar JC, Anderson LF, Baghaei P, et al. (Collaborative Group for the Meta-Analysis of Individual Patient Data in MDR-TB treatment–2017) (September 2018). "Treatment correlates of successful outcomes in pulmonary multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: an individual patient data meta-analysis". Lancet. 392 (10150): 821–834. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31644-1. PMC 6463280. PMID 30215381.

- ^ "Bedaquiline (Sirturo) Use During Pregnancy". www.drugs.com. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- ^ World Health Organization (2023). The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ^ "FDA approves first drug to treat multi-drug resistant tuberculosis". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). December 2012. Archived from the original on 19 December 2016.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control Prevention (October 2013). "Provisional CDC guidelines for the use and safety monitoring of bedaquiline fumarate (Sirturo) for the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis" (PDF). MMWR. Recommendations and Reports. 62 (RR-09): 1–12. PMID 24157696. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 November 2022. Retrieved 20 April 2024.

- ^ World Health Organization (February 2013). The use of bedaquiline in the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: interim policy guidance. World Health Organization (WHO). hdl:10665/84879. ISBN 978-92-4-150548-2. WHO/HTM/TB/2013.6.

- ^ Drugs.com: Sirturo Side Effects Archived 23 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Cox E, Laessig K (August 2014). "FDA approval of bedaquiline--the benefit-risk balance for drug-resistant tuberculosis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 371 (8): 689–91. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1314385. PMID 25140952.

- ^ a b Diacon AH, Pym A, Grobusch MP, de los Rios JM, Gotuzzo E, Vasilyeva I, et al. (August 2014). "Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and culture conversion with bedaquiline". The New England Journal of Medicine. 371 (8): 723–32. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1313865. PMID 25140958.

- ^ a b c Field SK (July 2015). "Bedaquiline for the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: great promise or disappointment?". Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease. 6 (4): 170–84. doi:10.1177/2040622315582325. PMC 4480545. PMID 26137207.

- ^ a b c Worley MV, Estrada SJ (November 2014). "Bedaquiline: a novel antitubercular agent for the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis". Pharmacotherapy. 34 (11): 1187–97. doi:10.1002/phar.1482. PMC 5028565. PMID 25203970.

- ^ a b Koul A, Vranckx L, Dhar N, Göhlmann HW, Özdemir E, Neefs JM, et al. (February 2014). "Delayed bactericidal response of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to bedaquiline involves remodelling of bacterial metabolism". Nature Communications. 5 (1): 3369. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.3369K. doi:10.1038/ncomms4369. PMC 3948051. PMID 24569628.

- ^ Andries K, Villellas C, Coeck N, Thys K, Gevers T, Vranckx L, et al. (10 July 2014). "Acquired resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to bedaquiline". PLOS ONE. 9 (7): e102135. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j2135A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0102135. PMC 4092087. PMID 25010492.

- ^ Protopopova M, Bogatcheva E, Nikonenko B, Hundert S, Einck L, Nacy CA (May 2007). "In search of new cures for tuberculosis". Medicinal Chemistry. 3 (3): 301–16. doi:10.2174/157340607780620626. PMID 17504204.

- ^ de Jonge MR, Koymans LH, Guillemont JE, Koul A, Andries K (June 2007). "A computational model of the inhibition of Mycobacterium tuberculosis ATPase by a new drug candidate R207910". Proteins. 67 (4): 971–80. doi:10.1002/prot.21376. PMID 17387738. S2CID 41795564.

- ^ Walker J, Tadena N (31 December 2012). "J&J Tuberculosis Drug Gets Fast-Track Clearance". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ^ Edney A (31 December 2012). "J&J&J Sirturo Wins FDA Approval to Treat Drug-Resistant TB". Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ^ "FDA Approves 1st New Tuberculosis Drug in 40 Years". ABC News. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- ^ Thomas K (31 December 2012). "F.D.A. Approves New Tuberculosis Drug". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 January 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- ^ Pinzler J, Mischke T (2016). "Die WHO - Im Griff der Lobbyisten?". Arte TV. Archived from the original on 24 April 2020. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ^ UNOPS (2015). "Stop TB Partnership, Global Drug Facility (GDF), The Bedaquiline Donation Program". www.stoptb.org. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ^ Dhillon A (29 March 2023). "Victory over big pharma opens door to cheaper tuberculosis drugs". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 21 February 2024. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- ^ "MSF demands J&J give up its patent monopoly on TB drug to put lives over profits". Médecins Sans Frontières Access Campaign. 26 April 2023. Archived from the original on 17 December 2023. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- ^ "Global Drug Facility Update on Access to Bedaquiline". Stop TB Partnership. 13 July 2023. Archived from the original on 9 March 2024. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ "India paves way for a cheaper anti-tuberculosis drug for kids". Hindustan Times. 22 July 2024. Archived from the original on 26 July 2024. Retrieved 22 July 2024.

- ^ World Health Organization (2015). The selection and use of essential medicines. Twentieth report of the WHO Expert Committee 2015 (including 19th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines and 5th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines for Children). Geneva: World Health Organization. pp. 26–30. hdl:10665/189763. ISBN 9789241209946. ISSN 0512-3054. WHO technical report series;994.

- ^ Gotham D, McKenna L, Frick M, Lessem E (18 September 2020). "Public investments in the clinical development of bedaquiline". PLOS ONE. 15 (9): e0239118. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1539118G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0239118. PMC 7500616. PMID 32946474.

- ^ Fiorillo M, Scatena C, Naccarato AG, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP (May 2021). "Bedaquiline, an FDA-approved drug, inhibits mitochondrial ATP production and metastasis in vivo, by targeting the gamma subunit (ATP5F1C) of the ATP synthase". Cell Death and Differentiation. 28 (9): 2797–2817. doi:10.1038/s41418-021-00788-x. PMC 8408289. PMID 33986463. S2CID 234496165.

- ^ "BPaMZ". TB Alliance. 12 July 2016. Archived from the original on 19 February 2017.

- ^ "Two new drug therapies might cure every form of tuberculosis". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 20 February 2017.