Ukrainian crisis

| History of Ukraine |

|---|

|

|

|

The Ukrainian crisis is the collective name for the 2013–14 Euromaidan protests associated with emergent social movement of integration of Ukraine into the European Union, the February 2014 Maidan revolution and the ensuing pro-Russian unrest.[1]

The crisis began on 21 November 2013, when then-president Viktor Yanukovych suspended preparations for the implementation of an association agreement with the European Union. The decision sparked mass protests from proponents of the agreement. The protests, in turn, precipitated a revolution that led to Yanukovych's ousting in February 2014. The ousting sparked unrest in the largely Russophone eastern and southern regions of Ukraine, from where Yanukovych had drawn most of his support.

Subsequently, the Russo-Ukrainian War began. Amidst Russia instigated wide unrest across southern and eastern Ukraine, Russian soldiers without insignias took control of strategic positions and infrastructure within the Ukrainian territory of Crimea. On 1 March 2014, the Federation Council of the Russian Federation unanimously adopted a resolution on petition of the President of Russia Vladimir Putin to use military force on territory of Ukraine.[2] The resolution was adopted several days later after the start of the Russian military operation on "Returning of Crimea". Russia then annexed Crimea after a widely criticised local referendum which was organized by Russia after the capturing of the Crimean Parliament by the Russian "little green men" and in which the population of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea voted to join the Russian Federation.[3][4] In April, demonstrations by pro-Russian groups in the Donbas area of Ukraine escalated into a war between the Ukrainian government and the Russian-backed separatist forces of the self-declared Donetsk and Luhansk People's Republics. In August, Russian military vehicles crossed the border in several locations of Donetsk Oblast.[5][6][7][8] The incursion by the Russian military was seen as responsible for the defeat of Ukrainian forces in early September 2014.[9][10][11][12]

Background

Despite being an independent country since 1991, Ukraine has been perceived by Russia as being part of its social and economic sphere of interest. Political analyst Iulian Chifu and his co-authors claim that in regard to Ukraine, Russia pursues a modernized version of the Brezhnev Doctrine on "limited sovereignty", which dictates that the sovereignty of Ukraine cannot be larger than that of the Warsaw Pact prior to the demise of the Soviet sphere of influence.[13] This claim is based on statements of Russian leaders that possible integration of Ukraine into NATO would jeopardize Russia's national security.[13]

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, both nations retained very close ties. At the same time, there were several sticking points, most importantly Ukraine's significant nuclear arsenal, which Ukraine agreed to abandon in the Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances on the condition that Russia (and the other signatories) would issue an assurance against threats or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of Ukraine. In 1999, Russia was one of the signatories of the Charter for European Security, where it "reaffirmed the inherent right of each and every participating State to be free to choose or change its security arrangements, including treaties of alliance, as they evolve".[14] Both would prove futile in 2014.[15]

Euromaidan and revolution

Ukraine became gripped by unrest when the Ukrainian government suspended preparations for signing the Ukraine–European Union Association Agreement with the European Union on 21 November 2013, to maintain its economic relations with Russia.[16] An organised political movement known as 'Euromaidan' demanded closer ties with the European Union, and the ousting of Yanukovych.[17] This movement was ultimately successful, culminating in the February 2014 revolution, which removed Yanukovych and his government.[18]

On 24 November 2013, clashes between protesters and police began. After a few days of demonstrations an increasing number of university students joined the protests.[19] The Euromaidan has been characterised as an event of major political symbolism for the European Union itself, particularly as "the largest ever pro-European rally in history."[20]

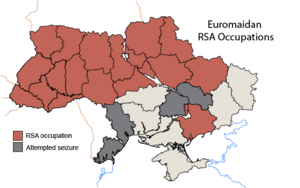

During 24 January 2014, western Ukrainian cities such as Ivano-Frankivsk, and Chernivtsi had protesters seize regional government buildings in protest of president Viktor Yanukovych. In Ivano-Frankivsk, nearly 1,500 protesters occupied the regional government building and barricaded themselves inside the building. The city of Chernivtsi saw crowds of protesters storm the governors office while police officers protected the building. Uzhgorod also had regional offices blockaded, and in the western city of Lviv barricades were being erected just after previously seizing the governor's office.[21]

The protests continued alongside heavy police presence,[22] regularly sub-freezing temperatures, and snow. Escalating violence from government forces in the early morning of 30 November caused the level of protests to rise, with 400,000–800,000 protesters, according to Russia's opposition politician Boris Nemtsov, demonstrating in Kyiv on the weekends of 1 December and 8 December.[23] In the preceding weeks, protest attendance had fluctuated from 50,000 to 200,000 during organised rallies.[24][25] Violent riots took place 1 December and 19 January through 25 January in response to police brutality and government repression.[26] Starting 23 January, several Western Ukrainian Oblast (province) Governor buildings and regional councils were occupied in a revolt by Euromaidan activists.[27] In the Russophone cities of Zaporizhzhia, Sumy, and Dnipropetrovsk, protesters also tried to take over their local government building, and were met with considerable force from both police and government supporters.[27]

2014 pro-Russian unrest

President Yanukovych was forced to flee on 23 February 2014, and protests by pro-Russian and anti-revolution protesters began in the largely Russophone region of Crimea.[28] These were followed by demonstrations in cities across eastern and southern Ukraine, including Donetsk, Luhansk, Kharkiv, and Odessa.

See also

- Casualties of the Ukrainian crisis

- Cold War II

- Ukraine–European Union relations

- Ukraine–NATO relations

References

- ^ German, Tracey; Karagiannis, Emmanuel (2018). "Introduction". The Ukrainian Crisis: The Role of, and Implications for, Sub-State and Non-State Actors. Routledge. ISBN 9781351737920.

- ^ The Federation Council gave approval on use of the Russian Armed Forces on territory of Ukraine (Совет Федерации дал согласие на использование Вооруженных Сил России на территории Украины). Federation Council. 1 March 2014

- ^ "BBC Radio 4 – Analysis, Maskirovka: Deception Russian-Style". BBC. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- ^ Lally, Kathy (17 April 2014). "Putin's remarks raise fears of future moves against Ukraine — The Washington Post". washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ Per Liljas (19 August 2014). "Rebels in Besieged Ukrainian City Reportedly Being Reinforced". Time. TIME. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ^ "How the war zone transformed between June 16 and Sept. 19". KyivPost. 25 September 2014. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ^ "Exclusive: Charred tanks in Ukraine point to Russian involvement". Reuters. 23 October 2014.

- ^ unian, 8 April 2015 debaltseve pocket created by Russian troops – yashin

- ^ Channel 4 News, 2 September 2014 tensions still high in Ukraine

- ^ Luke Harding (17 December 2014). "Ukraine ceasefire leaves frontline counting cost of war in uneasy calm". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ^ Higgins, Andrew; Kramer, Andrew E. (18 April 2014). "Pro-Russian Insurgents Balk at Terms of Pact in Ukraine". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

Doubts about the Kremlin's readiness to push pro-Russian militants to surrender their guns have been strengthened by its insistence that it has no hand in or control over the separatist unrest, which Washington and Kiev believe is the result of a covert Russian operation involving, in some places, the direct action of special forces.

- ^

Tsvetkova, Maria (10 May 2015). "Special Report: Russian soldiers quit over Ukraine". Reuters. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

Evidence for Russians fighting in Ukraine – Russian army equipment found in the country, testimony from soldiers' families and from Ukrainians who say they were captured by Russian paratroopers – is abundant.

- ^ a b Iulian Chifu; Oazu Nantoi; Oleksandr Sushko (2009). "Russia–Georgia War of August 2008: Ukrainian Approach" (PDF). The Russian Georgian War: A trilateral cognitive institutional approach of the crisis decision-making process. Bucharest: Editura Curtea Veche. p. 181. ISBN 978-973-1983-19-6. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- ^ "Istanbul Document 1999". Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. 19 November 1999. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ^ nbc 18 March 2014 [1], ukrainesolidaritycampaign the oligarchic rebellion in the donbas

- ^ "A Ukraine City Spins Beyond the Government's Reach". The New York Times. 15 February 2014.

- ^ Balmforth, Richard (12 December 2013). "Kiev protesters gather, EU dangles aid promise". Reuters. Archived from the original on 20 April 2014. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine Opposition Vows To Continue Struggle After Yanukovych Offer". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 25 January 2014. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ Students in Ukraine threaten indefinite national strike, Euronews (26 November 2013)

- ^ "Ukraine Offers Europe Economic Growth and More". The New York Times. 12 December 2013. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ^ "BBC News - Ukraine unrest: Protesters storm regional offices". Archived from the original on 24 January 2014.

- ^ Protests continue in Kiev ahead of Vilnius EU summit, Euronews (27 November 2013)

- ^ "Ukraine's capital Kiev gripped by huge pro-EU demonstration". BBC News. 8 December 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ Olzhas Auyezov and Jack Stubbs (22 December 2013). "Ukraine opposition urges more protests, forms political bloc". Reuters. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ Ukraine pro-Europe protesters hold first big rally of 2014, Reuters (12 January 2014)

- ^ "No Looting or Anarchy in this Euromaidan Revolution". Kyiv Post. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ a b Ukraine protests 'spread' into Russia-influenced east, BBC News (26 January 2014)

- ^ "Ukraine crisis fuels secession calls in pro-Russian south". The Guardian. 24 February 2014. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008.