Origin of COVID-19

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

|

|

|

|

There are several ongoing efforts by scientists, governments, international organisations, and others to determine the origin of SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. Most scientists say that as with other pandemics in human history, the virus is likely of zoonotic origin in a natural setting, and ultimately originated from a bat-borne virus.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7] Several other explanations, including many conspiracy theories, have been proposed about the origins of the virus.[8][9][10]

SARS-CoV-2 has close genetic similarity to multiple previously identified bat coronaviruses, suggesting it crossed over into humans from bats.[4][11][12][13][14] Research is ongoing as to whether SARS-CoV-2 came directly from bats or indirectly through any intermediate hosts.[15][16] Initial genome sequences of the virus showed little genetic diversity, although subsequently a number of stable variants emerged (some spreading more vigorously), indicating that the spillover event introducing SARS-CoV-2 to humans is likely to have occurred in late 2019.[17][18] Health authorities and scientists internationally state that as with the 2002–2004 outbreak of SARS-1, efforts to trace the specific geographic and taxonomic origins of SARS-CoV-2 could take years, and the results could be inconclusive.[19]

In January 2021, the World Health Assembly (decision-making body of the World Health Organization, WHO) commissioned a study on the origins of the virus, to be conducted jointly between WHO experts and Chinese scientists. In March 2021, the findings of this study were published online in a report to the WHO Commissioner-General.[1][20][21] Echoing the assessment of most virologists,[22][23][24] the report determined that the virus most likely had a zoonotic origin in bats, possibly transmitted through an intermediate host. It also stated that a laboratory origin for the virus was "extremely unlikely."[8][25]

Scientists found the conclusions of the WHO report to be helpful but noted that more work was needed.[26] In the United States, the European Union, and other countries, some criticised the lack of transparency and data access in the report's formulation.[27][28] The WHO issued its 30 March report alongside a statement of the WHO director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus saying that the matter "requires further investigation".[29][30][31] The U.S. government and 13 other countries and the EU issued statements on the same day, echoing Tedros's critique of the report for lacking transparency and data access in its formulation.[32][33] In a later press conference, the WHO director-general said it was "premature" for the WHO's report to rule out a potential link between a laboratory leak and called on China to provide 'raw data' and lab audits in a second phase of investigations.[27][34] On 12 October 2021, WHO announced a new team to study the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic.[35]

Earlier, on 22 July 2021, the Chinese government had held a press conference in which Zeng Yixin, Vice Health Minister of the National Health Commission (NHC), said that China would not participate in a second phase of the WHO's investigation, denouncing it as "shocking" and "arrogant".[36][37]

Scientific background

COVID-19 is caused by infection with a virus called severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). SARS-CoV-2 appears to have originated in bats and was spread to humans by zoonotic transfer.[22][25][38] Its exact evolutionary history, the identity and provenance of its most recent ancestors, and the place, time, and mechanism of transmission of the first human infection, remain unknown.[1][39] The biology and regional distribution of other coronaviruses in southeast Asia, including SARS-CoV, help scientists understand more about the origins of SARS-CoV-2.[40]

Taxonomically, SARS-CoV-2 is a virus of the species severe acute respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus (SARSr-CoV).[41] It is believed to have zoonotic origins and has close genetic similarity to bat coronaviruses, suggesting it emerged from a bat-borne virus.[4][12][13][14] Research is ongoing as to whether SARS-CoV-2 came directly from bats or indirectly through any intermediate hosts.[15][16] The virus shows little genetic diversity, indicating that the spillover event introducing SARS-CoV-2 to humans is likely to have occurred in late 2019.[18] Ultimately, the specific evolutionary history of SARS-CoV-2 in relation to other coronaviruses will be critical to understanding how, where and when the virus spilled over into a human population.[42]

Reservoir and origin

No natural reservoir for SARS-CoV-2 has been identified.[43] Prior to the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 as a pathogen infecting humans, there had been two previous zoonosis-based coronavirus epidemics, those caused by SARS-CoV-1 and MERS-CoV.[44]

The first known infections from SARS‑CoV‑2 were discovered in Wuhan, China.[12] The original source of viral transmission to humans remains unclear, as does whether the virus became pathogenic before or after the spillover event.[4][18][40] Because many of the early infectees were workers at the Huanan Seafood Market,[45][46] it has been suggested that the virus might have originated from the market.[4][47] However, other research indicates that visitors may have introduced the virus to the market, which then facilitated rapid expansion of the infections.[18][48] A March 2021 WHO-convened report stated that human spillover via an intermediate animal host was the most likely explanation, with direct spillover from bats next most likely. Introduction through the food supply chain and the Huanan Seafood Market was considered another possible, but less likely, explanation.[1] An analysis in November 2021, however, said that the earliest-known case had been misidentified and that the preponderance of early cases linked to the Huanan Market argued for it being the source.[49]

For a virus recently acquired through a cross-species transmission, rapid evolution is expected.[50] The mutation rate estimated from early cases of SARS-CoV-2 was of 6.54×10−4 per site per year.[1] Coronaviruses in general have high genetic plasticity,[51] but SARS-CoV-2's viral evolution is slowed by the RNA proofreading capability of its replication machinery.[52] For comparison, the viral mutation rate in vivo of SARS-CoV-2 has been found to be lower than that of influenza.[53]

Research into the natural reservoir of the virus that caused the 2002–2004 SARS outbreak has resulted in the discovery of many SARS-like bat coronaviruses, most originating in horseshoe bats. The closest match by far, published in Nature (journal) in February 2022, were viruses BANAL-52 (96.8% resemblance to SARS‑CoV‑2), BANAL-103 and BANAL-236, collected in three different species of bats in Feuang, Laos.[54][55][56] An earlier source published in February 2020 identified the virus RaTG13, collected in bats in Mojiang, Yunnan, China to be the closest to SARS‑CoV‑2, with 96.1% resemblance.[12][57] None of the above are its direct ancestor.[58]

Bats are considered the most likely natural reservoir of SARS‑CoV‑2.[1][59] Differences between the bat coronavirus and SARS‑CoV‑2 suggest that humans may have been infected via an intermediate host;[47] although the source of introduction into humans remains unknown.[60][43]

Although the role of pangolins as an intermediate host was initially posited (a study published in July 2020 suggested that pangolins are an intermediate host of SARS‑CoV‑2-like coronaviruses[61][62]), subsequent studies have not substantiated their contribution to the spillover.[1] Evidence against this hypothesis includes the fact that pangolin virus samples are too distant to SARS-CoV-2: isolates obtained from pangolins seized in Guangdong were only 92% identical in sequence to the SARS‑CoV‑2 genome (matches above 90 percent may sound high, but in genomic terms it is a wide evolutionary gap[63]). In addition, despite similarities in a few critical amino acids,[64] pangolin virus samples exhibit poor binding to the human ACE2 receptor.[65] Available scientific evidence suggests that SARS-CoV-2 has a natural zoonotic origin.[66][67][68][69][70] Yet its origin, which remains unknown, has become debated within the context of global geopolitical tensions.[70][71] Early in the pandemic, conspiracy theories spread on social media claiming that the virus was a biological weapon developed by China,[72] amplified by echo chambers in the American far-right.[73] Other conspiracy theories promoted misinformation that the virus is not communicable or was created to profit from new vaccines.[74]

Some politicians and scientists have speculated that the virus may have accidentally leaked from the Wuhan Institute of Virology.[71][75][76] This has led to calls in the media for further investigations into the matter.[77][78] Many virologists who have studied coronaviruses consider the possibility very remote.[74][79][80][81] The WHO-convened Global Study of the Origins of SARS-CoV-2 from March 2021 stated that such an explanation is extremely unlikely.[76][82] In an interview on 12 August 2021, Peter Ben Embarek, the chief investigator of the WHO team, told a Danish TV documentary that the WHO team felt pressured from Chinese scientists to put "extremely unlikely" as their assessment.[83]

Phylogenetics and taxonomy

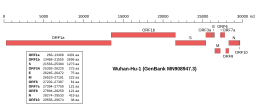

Genomic organisation of isolate Wuhan-Hu-1, the earliest sequenced sample of SARS-CoV-2 | |

| NCBI genome ID | 86693 |

|---|---|

| Genome size | 29,903 bases |

| Year of completion | 2020 |

| Genome browser (UCSC) | |

SARS‑CoV‑2 belongs to the broad family of viruses known as coronaviruses.[84] It is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA (+ssRNA) virus, with a single linear RNA segment. Coronaviruses infect humans, other mammals, including livestock and companion animals, and avian species.[85] Human coronaviruses are capable of causing illnesses ranging from the common cold to more severe diseases such as Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS, fatality rate ~34%). SARS-CoV-2 is the seventh known coronavirus to infect people, after 229E, NL63, OC43, HKU1, MERS-CoV, and the original SARS-CoV.[86]

Like the SARS-related coronavirus implicated in the 2003 SARS outbreak, SARS‑CoV‑2 is a member of the subgenus Sarbecovirus (beta-CoV lineage B).[87][88] Coronaviruses undergo frequent recombination.[69] The mechanism of recombination in unsegmented RNA viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 is generally by copy-choice replication, in which gene material switches from one RNA template molecule to another during replication.[89] The SARS-CoV-2 RNA sequence is approximately 30,000 bases in length,[90] relatively long for a coronavirus—which in turn carry the largest genomes among all RNA families.[91] Its genome consists nearly entirely of protein-coding sequences, a trait shared with other coronaviruses.[69]

A distinguishing feature of SARS‑CoV‑2 is its incorporation of a polybasic site cleaved by furin,[64][92] which appears to be an important element enhancing its virulence.[93] In SARS-CoV-2 the recognition site is formed by the incorporated 12 codon nucleotide sequence CCT CGG CGG GCA which corresponds to the amino acid sequence P RR A.[94] This sequence is upstream of an arginine and serine which forms the S1/S2 cleavage site (P RR A R↓S) of the spike protein.[95] Although such sites are a common naturally-occurring feature of other viruses within the Subfamily Orthocoronavirinae,[94] it appears in few other viruses from the Beta-CoV genus,[96] and it is unique among members of its subgenus for such a site.[64] The furin cleavage site PRRAR↓ is highly similar to that of the feline coronavirus, an alphacoronavirus 1 strain.[97]

Viral genetic sequence data can provide critical information about whether viruses separated by time and space are likely to be epidemiologically linked.[98] With a sufficient number of sequenced genomes, it is possible to reconstruct a phylogenetic tree of the mutation history of a family of viruses. By 12 January 2020, five genomes of SARS‑CoV‑2 had been isolated from Wuhan and reported by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CCDC) and other institutions;[90][99] the number of genomes increased to 42 by 30 January 2020.[100] A phylogenetic analysis of those samples showed they were "highly related with at most seven mutations relative to a common ancestor", implying that the first human infection occurred in November or December 2019.[100] Examination of the topology of the phylogenetic tree at the start of the pandemic also found high similarities between human isolates.[66] As of 21 August 2021,[update] 3,422 SARS‑CoV‑2 genomes, belonging to 19 strains, sampled on all continents except Antarctica were publicly available.[101]

On 11 February 2020, the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses announced that according to existing rules that compute hierarchical relationships among coronaviruses based on five conserved sequences of nucleic acids, the differences between what was then called 2019-nCoV and the virus from the 2003 SARS outbreak were insufficient to make them separate viral species. Therefore, they identified 2019-nCoV as a virus of Severe acute respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus.[102]

Origin scenarios

The origin of SARS-CoV-2 has been the subject of debate.[103] There are multiple proposed explanations for how SARS-CoV-2 was introduced into, and evolved adaptations suited to, the human population. There is significant evidence and agreement that the most likely original viral reservoir for SARS-CoV-2 is horseshoe bats, with the closest known viral relative being RaTG13. The evolutionary distance between SARS-CoV-2 and RaTG13 is estimated to be about 50 years (between 38 and 72 years).[104][105] The earliest human cases of SARS-CoV-2 were identified in Wuhan, but the index case remains unknown. RaTG13 was sampled from bats in Yunnan,[1][106] located roughly 1,300 km (810 mi) away from Wuhan,[107] and there are relatively few bat coronaviruses from Hubei province.[67] Each origin hypothesis attempts to explain this gap in virus evolution and location a different way. These scenarios continue to be investigated to identify the definitive origin of the virus.

Direct zoonotic transmission in a natural setting

The most direct pathway of introduction is direct zoonotic transmission (also known as spillover) from the reservoir species to humans. Scientists consider this to be a highly likely origin of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in humans. Human contact with bats has increased as human population centers encroach on bat habitats, leading to increased opportunities for spillover. Bats are a significant reservoir species for a diverse range of coronaviruses, and humans have been found with antibodies for them suggesting that this form of direct infection by bats is common. However, in this scenario, the direct ancestor of SARS-CoV-2 remains undiscovered in bats.[1][108]

Intermediate host

In addition to direct spillover, another pathway, considered highly likely by scientists, is that of transmission through an intermediate host.[7][109] Specifically, this implies that a cross species transmission occurred prior to the human outbreak and that it had pathogenic results on the animal. This pathway has the potential to allow for greater adaptation to human transmission via animals with more similar protein shapes to humans, though this is not required for the scenario to occur. The evolutionary separation from bat viruses is explained in this case by the virus' presence in an unknown species with less viral surveillance than bats.[110] The virus' ability to easily infect and adapt to additional species (including mink) provides evidence that such a route of transmission is possible.[1][109]

Cold/food chain

Another proposed introduction to humans is through fresh or frozen food products, referred to as the cold/food chain.[111] Scientists do not consider this to be a likely origin of SARS-CoV-2 in humans.[112] This scenario's source animal could be either a direct or intermediary species as described above. Many investigations centered around the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan, which had an early cluster of cases. While there have been food-borne outbreaks of human viruses in the past, and evidence of re-introduction of SARS-CoV-2 into China through imported frozen foods, investigations found no conclusive evidence of viral contamination in products at the Huanan Market.[1][113]

Laboratory incident

A final scenario, deemed unlikely by most experts,[22][23][24] and considered "extremely unlikely" by the WHO-convened study,[1] is the introduction of the virus to humans through a laboratory incident, known as the lab leak hypothesis.[23] This scenario would have involved laboratory staff becoming infected from contact with live bats (wild or captive), from contact with biological samples, or from contact with viruses being grown in vitro.[1][114] The Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) has performed research into bat coronaviruses since 2005, and identified the RaTG13 virus in 2013, which is the closest known relative of SARS-CoV-2.[23] WIV research interests have included investigations into the source of the 2002–2004 SARS outbreak and 2012 MERS outbreak, in collaboration with US researchers.[115][116] The proximity of the laboratory to the Huanan seafood market has led some to speculate there may be a link between the two,[117][118] and politicians, media personalities, and some scientists have called for further investigations into the matter.[119][120] Experts have ruled out intentional manipulation of the virus (i.e. biological engineering) as a plausible origin,[1][70][121][122][123] due to a lack of supporting evidence,[4][70][124] and growing evidence in favor of a natural origin.[125][126][127][128]

New York-based, National Institutes of Health–funded EcoHealth Alliance has been the subject of controversy and increased scrutiny due to its ties to the Wuhan Institute of Virology.[129][130][131][132] Under political pressure, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) withdrew funding to EcoHealth Alliance in July 2020.[133]

Subsequent investigations (such as the WHO-convened study) considered the possibility of a collected natural virus inadvertently infecting laboratory staff.[1][114][clarification needed] On 15 July 2021 WHO director-general Tedros Adhanom stated in a speech that there had been a "premature push" to discredit the idea of a lab leak.[134] Later on in the same speech, he expanded, "I was a lab technician, an immunologist, and worked in the lab. And lab accidents happen."[135] The WHO has planned a second phase of investigation that will include "audits of relevant laboratories and research institutions".[136] However, China has rejected this plan stating "it is impossible for us to accept such an origin-tracing plan".[137]

An even less likely lab-leak theory has been proposed by some members of the Chinese government who have claimed that the virus came from a U.S. military laboratory.[138] Chinese demands to investigate the U.S. lab at Fort Detrick have been said to be intended to deflect attention from Wuhan.[139]

Investigations

Chinese government

The first investigation conducted in China was by the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission, responding to hospitals reporting cases of pneumonia of unknown etiology, resulting in the closure of the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market on 1 January 2020 for sanitation and disinfection.[140] The market was originally suspected of being the source of the virus; however, the Chinese government and the WHO determined later that it was not.[25][141][142]

In April 2020, China imposed restrictions on publishing academic research on the novel coronavirus. Investigations into the origin of the virus would receive extra scrutiny and must be approved by Central Government officials.[143][144] The restrictions do not ban research or publication, including with non-Chinese researchers; Ian Lipkin, a US scientist, has been working with a team of Chinese researchers under the auspices of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, a Chinese government agency, to investigate the origin of the virus. Lipkin has long-standing relationships with Chinese officials, including premier Li Keqiang, because of his contributions to rapid testing for SARS in 2003.[145]

United States government

Trump administration

On 6 February 2020, the director of the White House's Office of Science and Technology Policy requested the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to convene a meeting of "experts, world class geneticists, coronavirus experts, and evolutionary biologists", to "assess what data, information and samples are needed to address the unknowns, in order to understand the evolutionary origins of COVID-19 and more effectively respond to both the outbreak and any resulting information".[146][147]

In April 2020, it was reported that the US intelligence community was investigating whether the virus came from an accidental leak from a Chinese lab. The hypothesis was one of several possibilities being pursued by the investigators. US Secretary of Defense Mark Esper said the results of the investigation were "inconclusive".[148][149] By the end of April 2020, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence said the US intelligence community believed the coronavirus was not man-made or genetically modified.[150][151]

US officials criticised the "terms of reference" allowing Chinese scientists to do the first phase of preliminary research.[20] On 15 January 2021, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said that to assist the WHO investigative team's work and ensure a transparent, thorough investigation of COVID-19's origin, the US was sharing new information and urging the WHO to press the Chinese government to address three specific issues, including the illnesses of several researchers inside the WIV in autumn 2019 "with symptoms consistent with both COVID-19 and common seasonal illnesses", the WIV's research on "RaTG13" and "gain of function", and the WIV's links to the People's Liberation Army.[152][153] On 18 January, the US called on China to allow the WHO's expert team to interview "care givers, former patients and lab workers" in the city of Wuhan, drawing a rebuke from the Chinese government. Australia also called for the WHO team to have access to "relevant data, information and key locations".[154]

A classified report from May 2020 by the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, a US government national laboratory, concluded that the hypothesis that the virus leaked from the WIV "is plausible and deserves further investigation", although the report also notes that the virus could have developed naturally, echoing the consensus of the American intelligence community, and provides no "smoking gun" towards either hypothesis.[155][156]

Biden administration

On 13 February 2021, the White House said it had "deep concerns" about both the way the WHO's findings were communicated and the process used to reach them. Mirroring concerns raised by the Trump administration, National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan stated that it was essential that the WHO-convened report be independent and "free from alteration by the Chinese government".[157] On 14 April 2021, the Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines, along with other Biden administration officials, said that they had not ruled out the possibility of a laboratory accident as the origin of the COVID-19 virus.[158]

On 26 May 2021, President Joe Biden directed the U.S. intelligence community to produce a report within 90 days on whether the COVID-19 virus originated from a human contact with an infected animal or from an accidental lab leak,[159] stating his national security staff said there is insufficient evidence to determine either hypothesis to be more likely.[160] On August 26, 2021, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence released an unclassified summary of their findings,[161] with the main point being that the report remained inconclusive as to the origin of the virus, with intelligence agencies divided on the question.[162] The report also concluded that the virus was most likely not genetically engineered, and that China had no foreknowledge of the virus prior to the outbreak. The report concluded that a final determination of the origin was unlikely without cooperation from the Chinese government, saying their prior lack of transparency "reflect[ed] in part China’s government’s own uncertainty about where an investigation could lead, as well as its frustration that the international community is using the issue to exert political pressure on China."[163] Chinese foreign ministry spokesman Wang Wenbin said that the US intelligence report was "unscientific and has no credibility".[164]

On 23 May 2021, The Wall Street Journal reported that a previously undisclosed US intelligence report stated that three researchers from the Wuhan Institute of Virology became ill enough in November 2019 to seek hospital care. The report did not specify what the illness was. Officials familiar with the intelligence differed as to the strength to which it corroborates the hypothesis that the virus responsible for COVID-19 was leaked from the WIV. The WSJ report notes that it is not unusual for people in China to go to the hospital with uncomplicated influenza or common cold symptoms.[165]

Yuan Zhiming, director of the WIV's Wuhan National Biosafety Laboratory, responded in the Global Times, a Chinese state media outlet, that the "claims are groundless".[166][167] Marion Koopmans, a member of the WHO study team, described the number of flu-like illnesses at the WIV in 2019 as "completely normal".[168] Workers at the WIV must provide yearly serum samples.[1][168] WIV virologist Shi Zhengli said in 2020 that, based on an evaluation of those serum samples, all staff tested negative for COVID-19 antibodies.[165]

The resurgence of the theory of a laboratory accident was fueled in part by the publication, in May 2021, of early emails between Anthony Fauci and scientists discussing the issue, before deliberate manipulation was ruled out as of March 2020.[169]

On 14 July 2021, the House Committee on Science, Space and Technology held the first congressional hearing on the origins of the virus. Bill Foster, an Illinois Democrat who chaired the hearing, said the Chinese government's lack of transparency is not in itself evidence of a lab leak and cautioned that answers may not be known even after the administration produces its intelligence report.[170] Expert witnesses Stanley Perlman and David Relman presented to the congressman different proposed explanations for the origins of the virus and how to conduct further investigations.[171]

On 16 July 2021, CNN reported that Biden administration officials considered the lab leak theory "as credible" as the natural origins theory.[172]

World Health Organization

The World Health Organization has declared that finding where SARS-CoV-2 came from is a priority and that it is "essential for understanding how the pandemic started."[173] In May 2020, the World Health Assembly, which governs the World Health Organization (WHO), passed a motion calling for a "comprehensive, independent and impartial" study into the COVID-19 pandemic. A record 137 countries, including China, co-sponsored the motion, giving overwhelming international endorsement to the study.[174] In mid 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) began negotiations with the government of China on conducting an official study into the origins of COVID-19.

In November 2020, the WHO published a two-phase study plan. The purpose of the first phase was to better understand how the virus "might have started circulating in Wuhan", and a second phase involves longer-term studies based on the findings of the first phase.[1][175] WHO director-general Tedros Adhanom said "We need to know the origin of this virus because it can help us to prevent future outbreaks," adding, "There is nothing to hide. We want to know the origin, and that's it." He also urged countries not to politicise the origin tracing process, saying that would only create barriers to learning the truth.[176]

Phase 1

For the first phase, the WHO formed a team of ten researchers with expertise in virology, public health and animals to conduct a thorough study.[177] One of the team's tasks was to retrospectively ascertain what wildlife was being sold in local wet markets in Wuhan.[178] The WHO's phase one team arrived and quarantined in Wuhan, Hubei, China in January 2021.[154][179]

Members of the team included Thea Fisher, John Watson, Marion Koopmans, Dominic Dwyer, Vladimir Dedkov, Hung Nguyen-Viet, Fabian Leendertz, Peter Daszak, Farag El Moubasher, and Ken Maeda. The team also included five WHO experts led by Peter Ben Embarek, two Food and Agriculture Organization representatives, and two representatives from the World Organisation for Animal Health.[1]

The inclusion of Peter Daszak in the team stirred controversy. Daszak is the head of EcoHealth Alliance, a nonprofit that studies spillover events, and has been a longtime collaborator of over 15 years with Shi Zhengli, Wuhan Institute of Virology's director of the Center for Emerging Infectious Diseases.[180][181] While Daszak is highly knowledgeable about Chinese laboratories and the emergence of diseases in the area, his close connection with the WIV was seen by some as a conflict of interest in the WHO's study.[180][182] When a BBC News journalist asked about his relationship with the WIV, Daszak said, "We file our papers, it's all there for everyone to see."[183]

The team was denied access to raw data, including the list of early patients, swabs, and blood samples.[184] It was allowed only a few hours of supervised access to the Wuhan Institute of Virology.[185]

Findings

In February 2021, after conducting part of their study, the WHO stated that the likely origin of COVID-19 was a zoonotic event from a virus circulating in bats, likely through another animal carrier, and that the time of transmission to humans was likely towards the end of 2019.[25]

The Chinese and the international experts who jointly carried out the WHO-convened study consider it "extremely unlikely" that COVID-19 leaked from a lab.[25][186][187][188] No evidence of a lab leak from the Wuhan Institute of Virology was found by the WHO team, with team leader Peter Ben Embarek stating that it was "very unlikely" due to the safety protocols in place.[25] During a 60 Minutes interview with Lesley Stahl, Peter Daszak, another member of the WHO team, described the investigation process to be a series of questions and answers between the WHO team and the Wuhan lab staff. Stahl made the comment that the team was "just taking their word for it", to which Daszak replied, "Well, what else can we do? There's a limit to what you can do and we went right up to that limit. We asked them tough questions. They weren't vetted in advance. And the answers they gave, we found to be believable—correct and convincing."[189]

The investigation also stated that transfer from animals to humans was unlikely to have occurred at the Huanan Seafood Market, since infections without a known epidemiological link were confirmed before the outbreak around the market.[25] In an announcement that surprised some foreign experts, the joint investigation concluded that early transmission via the cold chain of frozen products was "possible."[25]

In March 2021, the WHO published a written report with the results of the study.[190] The joint team stated that there are four scenarios for introduction:[113]

- direct zoonotic transmission to humans (spillover), assessed as "possible to likely"

- introduction through an intermediate host followed by a spillover, assessed as "likely to very likely"

- introduction through the (cold) food chain, assessed as "possible"

- introduction through a laboratory incident, assessed as "extremely unlikely"

The report mentions that direct zoonotic transmission to humans has a precedent, as most current human coronaviruses originated in animals. Zoonotic transmission is also supported by the fact that RaTG13 binds to hACE2, although the fit is not optimal.[1][191]

The investigative team noted the requirement for further studies, noting that these would "potentially increase knowledge and understanding globally."[192][1]: 9

Reactions

WHO director-general Tedros Adhanom, who was not directly involved with the investigation, said he was ready to dispatch additional missions involving specialist experts and that further research was required. He said in a statement, "Some explanations may be more probable than others, but for now all possibilities remain on the table".[193] He also said, "We have not yet found the source of the virus, and we must continue to follow the science and leave no stone unturned as we do." Tedros also called on China to provide "more timely and comprehensive data sharing" as part of future investigations.[194]

News outlets noted that though it was irrealistic to expect quick and huge results from the report, it "offered few clear-cut conclusions regarding the start of the pandemic", "failed to audit the Chinese official position at some parts of the report", and was "biased according to critics".[195][196][197][198] Other scientists praised how the report details the pathways that can shed light on the origin, if explored later.[199]

After the publication of the report, politicians, talk show hosts, journalists, and some scientists advanced unsupported claims that SARS-CoV-2 may have come from the WIV.[200] In the United States, calls to investigate a laboratory leak reached a "fever pitch," fueling aggressive rhetoric resulting in antipathy towards people of Asian ancestry,[200][201] and the bullying of scientists.[202][203][204] The United States, European Union, and 13 other countries criticised the WHO-convened study, calling for transparency from China and access to the raw data and original samples.[205] Chinese officials described these criticisms as an attempt to politicise the study.[206] Scientists involved in the WHO report, including Liang Wannian, John Watson, and Peter Daszak, objected to the criticism, and said that the report was an example of the collaboration and dialogue required to successfully continue investigations into the matter.[207]

In a letter published in Science, a number of scientists, including Ralph Baric, argued that the accidental laboratory leak hypothesis had not been sufficiently investigated and remained possible, calling for greater clarity and additional data.[75] Their letter was criticized by some virologists and public health experts, who said that a "hostile" and "divisive" focus on the WIV was unsupported by evidence, and would cause Chinese scientists and authorities to share less, rather than more data.[200]

Phase 2

On 27 May 2021, Danish epidemiologist Tina Fischer spoke on the This Week in Virology podcast, advocating for a second phase of the study to audit blood samples for COVID-19 antibodies in China.[208][209] WHO-convened study team member Marion Koopmans, on that same broadcast, advocated for WHO member states to make a decision on the second phase of the study, though she also cautioned that an investigatory audit of the laboratory itself may be inconclusive.[208][209] In early July 2021, WHO emergency chief Michael Ryan said the final details of phase 2 were being worked out in negotiations between WHO and its member states, as the WHO works "by persuasion" and cannot compel any member state (including China) to cooperate.[210]

In July 2021 China rejected WHO requests for greater transparency, cooperation, and access to data as part of Phase 2. On 16 July 2021, Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian declared that China's position was that future investigations should be conducted elsewhere and should focus on cold chain transmission and the US military's labs.[211] On 22 July 2021, the Chinese government held a press conference in which Zeng Yixin, Vice Health Minister of the National Health Commission (NHC), said that China would not participate in a second phase of the WHO's investigation, denouncing it as "shocking" and "arrogant".[36] He elaborated "In some aspects, the WHO's plan for next phase of investigation of the coronavirus origin doesn't respect common sense, and it's against science. It's impossible for us to accept such a plan."[37]

The Lancet COVID-19 Commission task force

In November 2020, an international task force led by Peter Daszak, president of EcoHealth Alliance, was formed as part of The Lancet COVID-19 Commission, backed by the medical journal The Lancet.[212] Daszak stated that the task force was formed to "conduct a thorough and rigorous investigation into the origins and early spread of SARS-CoV-2". The task force has twelve members with backgrounds in One Health, outbreak investigation, virology, lab biosecurity and disease ecology.[213][214] The task force plans to analyse scientific findings and does not plan to visit China.[212] In June 2021, The Lancet announced that Daszak had recused himself from the commission.[215] On September 25, 2021, the task force work was folded after procedural concerns and a need to broaden its scope to examine transparency and government regulation of risky laboratory research.[216]

Independent investigations

In June 2021, the NIH announced that a set of sequence data had been removed from the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) in June 2020. The removal was performed according to standard practice at the request of the investigators who owned the rights to the sequences, with the investigators' rationale that the sequences would be submitted to another database.[217][218] The investigators subsequently published a paper in an academic journal the same month they were removed from the NIH database which described the sequences in detail and discussed their evolutionary relationship to other sequences, but did not include the raw data.[219] Virologist David Robertson said that it was difficult to conclude it was a cover-up rather than the more likely explanation: a mundane deletion of data without malfeasance.[220][221] The missing genetic sequence data was restored in a correction published 29 July 2021 after it was stated to be a copy-edit error.[222][223]

International calls for investigations

In April 2020, Australian foreign minister Marise Payne and Australian prime minister Scott Morrison called for an independent international inquiry into the origins of the coronavirus pandemic.[224][225] A few days later, German chancellor Angela Merkel also pressed China for transparency about the origin of the coronavirus, following similar concerns raised by the French president Emmanuel Macron.[226] The UK also expressed support for an investigation, although both France and UK said the priority at the time was to first fight the virus.[227][228] Some public health experts have also called for an independent examination of COVID-19's origins, "arguing WHO does not have the political clout to conduct such a forensic analysis".[229] In May 2021, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau told reporters Canada would "support the call by the United States and others to better understand the origins of COVID-19."[230][231] In June 2021, at the G7 summit in Cornwall, the attending leaders issued a joint statement calling for a new investigation, citing China's refusal to cooperate with certain aspects of the original WHO-convened study.[232] This resistance to international pressure was one of the key findings of a Wall Street Journal investigation into the pandemic origin.[233]

The divisive nature of the debate has led scientists to call for less political pressure on the topic.[169] Public health analysts have remarked that the debate over the origins of SARS-CoV-2 is fueling unnecessary confrontation, resulting in bullying and harassment of scientists,[234] and is deepening existing geopolitical tensions and hindering collaboration at a time where such mutual cooperation is required, both to deal with the current pandemic and in preparation for future such outbreaks.[71][235] This comes in the face of scientists having predicted such events for decades: according to Katie Woolaston, researcher at the Queensland University of Technology, "The environmental drivers of pandemics are not being widely discussed". The debate comes at a moment of difficult global relations with Chinese authorities. Researchers have noted that the politicisation of the debate is making the process more difficult, and that words are often twisted to become "fodder for conspiracy theories."[236][237] A letter published in The Lancet in July 2021 remarked that the atmosphere of speculation surrounding the issue was of no help in making an objective assessment of the situation.[120] In response to this letter, in a communication published in the same journal, a small group of scientists opposed the idea that scientists should promote unity and call for openness to alternative hypotheses.[238] Despite the unlikelihood of the event, and although definitive answers are likely to take years of research, biosecurity experts have called for a review of global biosecurity policies, citing known gaps in international standards for biosafety.[71][236] The situation has also reignited a debate over gain-of-function research, although the intense political rhetoric surrounding the issue has threatened to sideline serious inquiry over policy in this domain.[239]

See also

- Scientific Advisory Group for Origins of Novel Pathogens

- World Health Organization's response to the COVID-19 pandemic

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t "Virus origin / Origins of the SARS-CoV-2 virus". www.who.int. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

WHO-convened Global Study of the Origins of SARS-CoV-2

- ^ "The COVID-19 coronavirus epidemic has a natural origin, scientists say – Scripps Research's analysis of public genome sequence data from SARS‑CoV‑2 and related viruses found no evidence that the virus was made in a laboratory or otherwise engineered". EurekAlert!. Scripps Research Institute. 17 March 2020. Archived from the original on 11 May 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Latinne, Alice; Hu, Ben; Olival, Kevin J.; Zhu, Guangjian; Zhang, Libiao; Li, Hongying; Chmura, Aleksei A.; Field, Hume E.; Zambrana-Torrelio, Carlos; Epstein, Jonathan H.; Li, Bei; Zhang, Wei; Wang, Lin-Fa; Shi, Zheng-Li; Daszak, Peter (25 August 2020). "Origin and cross-species transmission of bat coronaviruses in China". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 4235. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.4235L. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-17687-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7447761. PMID 32843626.

- ^ a b c d e f Andersen KG, Rambaut A, Lipkin WI, Holmes EC, Garry RF (17 March 2020). "Correspondence: The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2". Nature Medicine. 26 (4): 450–452. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0820-9. PMC 7095063. PMID 32284615.

- ^ Gorman, James; Zimmer, Carl (13 May 2021). "Another Group of Scientists Calls for Further Inquiry Into Origins of the Coronavirus". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ Hu, Ben; Guo, Hua; Zhou, Peng; Shi, Zheng-Li (6 October 2020). "Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 19 (3): 141–154. doi:10.1038/s41579-020-00459-7. ISSN 1740-1526. PMC 7537588. PMID 33024307.

- ^ a b Kramer, Jillian (30 March 2021). "Here's what the WHO report found on the origins of COVID-19". Science. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

Most scientists are not surprised by the report's conclusion that SARS-CoV-2 most likely jumped from an infected bat or pangolin to another animal and then to a human.

- ^ a b Horowitz, Josh; Stanway, David (9 February 2021). "COVID may have taken 'convoluted path' to Wuhan, WHO team leader says". Reuters. Archived from the original on 10 February 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ Pauls K, Yates J (27 January 2020). "Online claims that Chinese scientists stole coronavirus from Winnipeg lab have 'no factual basis'". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 8 February 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- ^ "China's rulers see the coronavirus as a chance to tighten their grip". The Economist. 8 February 2020. Archived from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ^ Latinne, Alice; Hu, Ben; Olival, Kevin J.; et al. (25 August 2020). "Origin and cross-species transmission of bat coronaviruses in China". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 4235. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.4235L. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-17687-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7447761. PMID 32843626.

- ^ a b c d Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, et al. (February 2020). "A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin". Nature. 579 (7798): 270–273. Bibcode:2020Natur.579..270Z. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. PMC 7095418. PMID 32015507.

- ^ a b Perlman S (February 2020). "Another Decade, Another Coronavirus". The New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (8): 760–762. doi:10.1056/NEJMe2001126. PMC 7121143. PMID 31978944.

- ^ a b Benvenuto D, Giovanetti M, Ciccozzi A, Spoto S, Angeletti S, Ciccozzi M (April 2020). "The 2019-new coronavirus epidemic: Evidence for virus evolution". Journal of Medical Virology. 92 (4): 455–459. doi:10.1002/jmv.25688. PMC 7166400. PMID 31994738.

- ^ a b Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV): situation report, 22 (Report). World Health Organization. 11 February 2020. hdl:10665/330991.

- ^ a b Shield C (7 February 2020). "Coronavirus: From bats to pangolins, how do viruses reach us?". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ "Genomic epidemiology of novel coronavirus – Global subsampling". Nextstrain. Archived from the original on 20 April 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d Cohen J (January 2020). "Wuhan seafood market may not be source of novel virus spreading globally". Science. doi:10.1126/science.abb0611. S2CID 214574620.

- ^ Cadell, Cate (11 December 2020). "One year on, Wuhan market at epicentre of virus outbreak remains barricaded and empty". Reuters. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ^ a b Nebehay, Stephanie (10 November 2020). "U.S. denounces terms for WHO-led inquiry into COVID origins". Reuters. Archived from the original on 25 December 2020. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ Davidson, Helen (9 February 2021). "WHO team says theory Covid began in Wuhan lab 'extremely unlikely'". the Guardian. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ a b c Frutos, Roger; Serra-Cobo, Jordi; Chen, Tianmu; Devaux, Christian A. (October 2020). "COVID-19: Time to exonerate the pangolin from the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 to humans". Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 84: 104493. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104493. ISSN 1567-1348. PMC 7405773. PMID 32768565.

- ^ a b c d Maxmen, Amy; Mallapaty, Smriti (8 June 2021). "The COVID lab-leak hypothesis: what scientists do and don't know". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-01529-3. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ a b Osuchowski, Marcin F; Winkler, Martin S; Skirecki, Tomasz; Cajander, Sara; Shankar-Hari, Manu; Lachmann, Gunnar; Monneret, Guillaume; Venet, Fabienne; Bauer, Michael; Brunkhorst, Frank M; Weis, Sebastian; Garcia-Salido, Alberto; Kox, Matthijs; Cavaillon, Jean-Marc; Uhle, Florian; Weigand, Markus A; Flohé, Stefanie B; Wiersinga, W Joost; Almansa, Raquel; de la Fuente, Amanda; Martin-Loeches, Ignacio; Meisel, Christian; Spinetti, Thibaud; Schefold, Joerg C; Cilloniz, Catia; Torres, Antoni; Giamarellos-Bourboulis, Evangelos J; Ferrer, Ricard; Girardis, Massimo; Cossarizza, Andrea; Netea, Mihai G; van der Poll, Tom; Bermejo-Martín, Jesús F; Rubio, Ignacio (6 May 2021). "The COVID-19 puzzle: deciphering pathophysiology and phenotypes of a new disease entity". The Lancet. Respiratory Medicine. 9 (6): 622–642. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00218-6. ISSN 2213-2600. PMC 8102044. PMID 33965003.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Fujiyama, Emily Wang; Moritsugu, Ken (11 February 2021). "EXPLAINER: What the WHO coronavirus experts learned in Wuhan". Associated Press News. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ Mallapati, Smriti (1 April 2021). "After the WHO report: what's next in the search for COVID's origins". Nature News. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ a b Cohen, Jon (17 July 2021). "With call for 'raw data' and lab audits, WHO chief pressures China on pandemic origin probe". Science. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ Cohen, Jon (13 February 2021). "China refused to provide WHO team with raw data on early COVID cases, team member says". Reuters. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ "Virus origin / Origins of the SARS-CoV-2 virus". www.who.int.

- ^ Maxmen, Amy (30 March 2021). "WHO report into COVID pandemic origins zeroes in on animal markets, not labs". Nature. pp. 173–174. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-00865-8. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ Shepherd, Christian (31 March 2021). "China rejects WHO criticism and says Covid lab-leak theory 'ruled out'". www.ft.com. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ Mulier, Thomas (31 March 2021). "WHO Chief Faults Covid Report for Dismissing Lab Leak Theory".

- ^ Reuters Staff (31 March 2021). "U.S., 13 countries concerned WHO COVID-19 origin study was delayed, lacked access - statement". Reuters. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Jordans, Frank; Cheng, Maria (15 July 2021). "WHO chief says it was 'premature' to rule out COVID lab leak". AP News. The Associated Press. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ Mueller, Benjamin (12 October 2021). "W.H.O. Will Announce New Team to Study Coronavirus Origins - "This new group can do all the fancy footwork it wants, but China's not going to cooperate," one expert said". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- ^ a b Buckley, Chris (22 July 2021). "China denounces the W.H.O.'s call for another look at the Wuhan lab as 'shocking' and 'arrogant.'". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ a b Ben Westcott, Isaac Yee and Yong Xiong. "Chinese government rejects WHO plan for second phase of Covid-19 origins study". CNN. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ Barh, Debmalya; Silva Andrade, Bruno; Tiwari, Sandeep; Giovanetti, Marta; Góes-Neto, Aristóteles; Alcantara, Luiz Carlos Junior; Azevedo, Vasco; Ghosh, Preetam (1 September 2020). "Natural selection versus creation: a review on the origin of SARS-COV-2". Le Infezioni in Medicina. 28 (3): 302–311. ISSN 1124-9390. PMID 32920565. Archived from the original on 2 November 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ Relman, David A. (24 November 2020). "Opinion: To stop the next pandemic, we need to unravel the origins of COVID-19". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (47): 29246–29248. doi:10.1073/pnas.2021133117. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 7703598. PMID 33144498.

- ^ a b Eschner K (28 January 2020). "We're still not sure where the Wuhan coronavirus really came from". Popular Science. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ Fox D (24 January 2020). "What you need to know about the Wuhan coronavirus". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00209-y. PMID 33483684. S2CID 213064026.

- ^ a b Holmes EC, Goldstein SA, Rasmussen AL, Robertson DL, Crits-Christoph A, Wertheim JO, Anthony SJ, Barclay WS, Boni MF, Doherty PC, Farrar J (August 2021). "The Origins of SARS-CoV-2: A Critical Review". Cell. 184 (19): 4848–4856. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.08.017. PMC 8373617. PMID 34480864.

- ^ V'kovski P, Kratzel A, Steiner S, Stalder H, Thiel V (March 2021). "Coronavirus biology and replication: implications for SARS-CoV-2". Nat Rev Microbiol (Review). 19 (3): 155–170. doi:10.1038/s41579-020-00468-6. PMC 7592455. PMID 33116300.

- ^ Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. (15 February 2020). "Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China". The Lancet. 395 (10223): 497–506. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. PMC 7159299. PMID 31986264. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. (15 February 2020). "Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study". The Lancet. 395 (10223): 507–513. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. PMC 7135076. PMID 32007143.

- ^ a b Cyranoski D (26 February 2020). "Mystery deepens over animal source of coronavirus". Nature. 579 (7797): 18–19. Bibcode:2020Natur.579...18C. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00548-w. PMID 32127703.

- ^ Yu WB, Tang GD, Zhang L, Corlett RT (21 February 2020). "Decoding evolution and transmissions of novel pneumonia coronavirus using the whole genomic data". ChinaXiv. doi:10.12074/202002.00033 (inactive 31 October 2021). Archived from the original on 23 February 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of October 2021 (link) - ^ Worobey M (December 2021). "Dissecting the early COVID-19 cases in Wuhan". Science. 374 (6572): 1202–1204. Bibcode:2021Sci...374.1202W. doi:10.1126/science.abm4454. PMID 34793199. S2CID 244403410.

- ^ Kang L, He G, Sharp AK, Wang X, Brown AM, Michalak P, Weger-Lucarelli J (August 2021). "A selective sweep in the Spike gene has driven SARS-CoV-2 human adaptation". Cell. 184 (17): 4392–4400.e4. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.07.007. PMC 8260498. PMID 34289344.

- ^ Decaro N, Lorusso A (May 2020). "Novel human coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2): A lesson from animal coronaviruses". Veterinary Microbiology. 244: 108693. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2020.108693. PMC 7195271. PMID 32402329.

- ^ Robson F, Khan KS, Le TK, Paris C, Demirbag S, Barfuss P, et al. (August 2020). "Coronavirus RNA Proofreading: Molecular Basis and Therapeutic Targeting [published correction appears in Mol Cell. 2020 Dec 17;80(6):1136–1138]". Molecular Cell. 79 (5): 710–727. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2020.07.027. PMC 7402271. PMID 32853546.

- ^ Tao K, Tzou PL, Nouhin J, Gupta RK, de Oliveira T, Kosakovsky Pond SL, Fera D, Shafer RW (December 2021). "The biological and clinical significance of emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants". Nature Reviews Genetics. 22 (12): 757–773. doi:10.1038/s41576-021-00408-x. PMC 8447121. PMID 34535792.

- ^ Temmam, Sarah; Vongphayloth, Khamsing; Salazar, Eduard Baquero; Munier, Sandie; Bonomi, Max; Régnault, Béatrice; Douangboubpha, Bounsavane; Karami, Yasaman; Chretien, Delphine; Sanamxay, Daosavanh; Xayaphet, Vilakhan (February 2022). "Bat coronaviruses related to SARS-CoV-2 and infectious for human cells". Nature. 604 (7905): 330–336. Bibcode:2022Natur.604..330T. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04532-4. PMID 35172323. S2CID 246902858.

- ^ Mallapaty, Smriti (24 September 2021). "Closest known relatives of virus behind COVID-19 found in Laos". Nature. 597 (7878): 603. Bibcode:2021Natur.597..603M. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-02596-2. PMID 34561634. S2CID 237626322.

- ^ "Newly Discovered Bat Viruses Give Hints to Covid's Origins". The New York Times. 14 October 2021.

- ^ "Bat coronavirus isolate RaTG13, complete genome". National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). 10 February 2020. Archived from the original on 15 May 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ^ "The 'Occam's Razor Argument' Has Not Shifted in Favor of a Lab Leak". Snopes.com. Snopes. 16 July 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, Niu P, Yang B, Wu H, et al. (February 2020). "Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding". The Lancet. 395 (10224): 565–574. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. PMC 7159086. PMID 32007145.

- ^ O'Keeffe J, Freeman S, Nicol A (21 March 2021). The Basics of SARS-CoV-2 Transmission. Vancouver, BC: National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health (NCCEH). ISBN 978-1-988234-54-0. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ Xiao K, Zhai J, Feng Y, Zhou N, Zhang X, Zou JJ, Li N, Guo Y, Li X, Shen X, Zhang Z, Shu F, Huang W, Li Y, Zhang Z, Chen RA, Wu YJ, Peng SM, Huang M, Xie WJ, Cai QH, Hou FH, Chen W, Xiao L, Shen Y (July 2020). "Isolation of SARS-CoV-2-related coronavirus from Malayan pangolins". Nature. 583 (7815): 286–289. Bibcode:2020Natur.583..286X. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2313-x. PMID 32380510. S2CID 218557880.

- ^ Zhao J, Cui W, Tian BP (2020). "The Potential Intermediate Hosts for SARS-CoV-2". Frontiers in Microbiology. 11: 580137. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2020.580137. PMC 7554366. PMID 33101254.

- ^ "Why it's so tricky to trace the origin of COVID-19". Science. National Geographic. 10 September 2021.

- ^ a b c Hu B, Guo H, Zhou P, Shi ZL (October 2020). "Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 19 (3): 141–154. doi:10.1038/s41579-020-00459-7. PMC 7537588. PMID 33024307.

- ^ Giovanetti M, Benedetti F, Campisi G, Ciccozzi A, Fabris S, Ceccarelli G, Tambone V, Caruso A, Angeletti S, Zella D, Ciccozzi M (November 2020). "Evolution patterns of SARS-CoV-2: Snapshot on its genome variants". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 538: 88–91. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.10.102. PMC 7836704. PMID 33199021. S2CID 226988090.

- ^ a b Sun J, He WT, Wang L, Lai A, Ji X, Zhai X, Li G, Suchard MA, Tian J, Zhou J, Veit M, Su S (May 2020). "COVID-19: Epidemiology, Evolution, and Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives". Trends in Molecular Medicine. 26 (5): 483–495. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2020.02.008. PMC 7118693. PMID 32359479.

- ^ a b Zhang, Yong-Zhen; Holmes, Edward C. (April 2020). "A Genomic Perspective on the Origin and Emergence of SARS-CoV-2". Cell. 181 (2): 223–227. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.035. PMC 7194821. PMID 32220310.

- ^ Seyran, Murat; Pizzol, Damiano; Adadi, Parise; El‐Aziz, Tarek M. A.; Hassan, Sk. Sarif; Soares, Antonio; Kandimalla, Ramesh; Lundstrom, Kenneth; Tambuwala, Murtaza; Aljabali, Alaa A. A.; Lal, Amos; Azad, Gajendra K.; Choudhury, Pabitra P.; Uversky, Vladimir N.; Sherchan, Samendra P.; Uhal, Bruce D.; Rezaei, Nima; Brufsky, Adam M. (March 2021). "Questions concerning the proximal origin of SARS‐CoV‐2". Journal of Medical Virology. 93 (3): 1204–1206. doi:10.1002/jmv.26478. ISSN 0146-6615. PMC 7898912. PMID 32880995.

There is a consensus that severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) originated naturally from bat coronaviruses (CoVs)

- ^ a b c Singh D, Yi SV (April 2021). "On the origin and evolution of SARS-CoV-2". Experimental & Molecular Medicine. 53 (4): 537–547. doi:10.1038/s12276-021-00604-z. PMC 8050477. PMID 33864026.

- ^ a b c d Frutos R, Gavotte L, Devaux CA (March 2021). "Understanding the origin of COVID-19 requires to change the paradigm on zoonotic emergence from the spillover model to the viral circulation model". Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 95: 104812. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2021.104812. PMC 7969828. PMID 33744401.

- ^ a b c d Maxmen A (June 2021). "Divisive COVID 'lab leak' debate prompts dire warnings from researchers". Nature. 594 (7861): 15–16. Bibcode:2021Natur.594...15M. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-01383-3. PMID 34045757. S2CID 235232290.

- ^ Zoumpourlis V, Goulielmaki M, Rizos E, Baliou S, Spandidos DA (October 2020). "The COVID‑19 pandemic as a scientific and social challenge in the 21st century". Mol Med Rep (Review). 22 (4): 3035–3048. doi:10.3892/mmr.2020.11393. PMC 7453598. PMID 32945405.

- ^ Qin A, Wang V, Hakim D (20 November 2020). "How Steve Bannon and a Chinese Billionaire Created a Right-Wing Coronavirus Media Sensation". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021.

- ^ a b Hakim MS (February 2021). "SARS-CoV-2, Covid-19, and the debunking of conspiracy theories". Reviews in Medical Virology. 31 (6): e2222. doi:10.1002/rmv.2222. PMC 7995093. PMID 33586302.

- ^ a b Bloom, Jesse D.; Chan, Yujia Alina; Baric, Ralph S.; Bjorkman, Pamela J.; Cobey, Sarah; Deverman, Benjamin E.; Fisman, David N.; Gupta, Ravindra; Iwasaki, Akiko; Lipsitch, Marc; Medzhitov, Ruslan; Neher, Richard A.; Nielsen, Rasmus; Patterson, Nick; Stearns, Tim; Nimwegen, Erik van; Worobey, Michael; Relman, David A. (14 May 2021). "Investigate the origins of COVID-19". Science. 372 (6543): 694. Bibcode:2021Sci...372..694B. doi:10.1126/science.abj0016. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 33986172. S2CID 234487267.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lay-url=ignored (help) - ^ a b "WHO-convened global study of origins of SARS-CoV-2: China Part". www.who.int. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ Beaumont P (27 May 2021). "Did Covid come from a Wuhan lab? What we know so far". The Guardian.

- ^ Gorman J, Zimmer C (13 May 2021). "Another Group of Scientists Calls for Further Inquiry Into Origins of the Coronavirus". The New York Times.

- ^ Zimmer C, Gorman J, Mueller B (27 May 2021). "Scientists Don't Want to Ignore the 'Lab Leak' Theory, Despite No New Evidence". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ Graham RL, Baric RS (May 2020). "SARS-CoV-2: Combating Coronavirus Emergence". Immunity. 52 (5): 734–736. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2020.04.016. PMC 7207110. PMID 32392464.

- ^ Gorman, James; Zimmer, Carl (14 June 2021). "Scientist opens up about his early email to Fauci on virus origins". The New York Times.

- ^ Gorman J, Barnes JE (26 March 2021). "The C.D.C.'s ex-director offers no evidence in favoring speculation that the coronavirus originated in a lab". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Dyer, Owen (13 August 2021). "Covid-19: China pressured WHO team to dismiss lab leak theory, claims chief investigator". BMJ. BMJ News. pp. n2023. doi:10.1136/bmj.n2023.

A World Health Organisation mission to study the covid pandemic's origins in China, which announced in February that the possibility that the virus had escaped from a laboratory needed no further investigation,1 was put under pressure by Chinese scientists who made up half the team to reach that conclusion, the scientist who led the mission has said...Discussing the team's findings before leaving China, Ben Embarek told reporters that a lab leak was "extremely unlikely." Asked by Denmark's TV2 if that wording was a Chinese requirement, he said, "It was the category we chose to put it in at the end, yes." This did not mean it was not impossible, he added.

- ^ Fox D (January 2020). "What you need to know about the novel coronavirus". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00209-y. PMID 33483684. S2CID 213064026.

- ^ V'kovski P, Kratzel A, Steiner S, Stalder H, Thiel V (March 2021). "Coronavirus biology and replication: implications for SARS-CoV-2". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 19 (3): 155–170. doi:10.1038/s41579-020-00468-6. PMC 7592455. PMID 33116300.

- ^ Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, Zhao X, Huang B, Shi W, Lu R, Niu P, Zhan F, Ma X, Wang D, Xu W, Wu G, Gao GF, Tan W (February 2020). "A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019". The New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (8): 727–733. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. PMC 7092803. PMID 31978945.

- ^ "Phylogeny of SARS-like betacoronaviruses". nextstrain. Archived from the original on 20 January 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ Wong AC, Li X, Lau SK, Woo PC (February 2019). "Global Epidemiology of Bat Coronaviruses". Viruses. 11 (2): 174. doi:10.3390/v11020174. PMC 6409556. PMID 30791586.

- ^ Jackson B, Boni MF, Bull MJ, Colleran A, Colquhoun RM, Darby AC, Haldenby S, Hill V, Lucaci A, McCrone JT, Nicholls SM, O'Toole Á, Pacchiarini N, Poplawski R, Scher E, Todd F, Webster HJ, Whitehead M, Wierzbicki C, Loman NJ, Connor TR, Robertson DL, Pybus OG, Rambaut A (September 2021). "Generation and transmission of interlineage recombinants in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic". Cell. 184 (20): 5179–5188.e8. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.08.014. PMC 8367733. PMID 34499854. S2CID 237099659.

- ^ a b "CoV2020". GISAID EpifluDB. Archived from the original on 12 January 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ Kim D, Lee JY, Yang JS, Kim JW, Kim VN, Chang H (May 2020). "The Architecture of SARS-CoV-2 Transcriptome". Cell. 181 (4): 914–921.e10. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.011. PMC 7179501. PMID 32330414.

- ^ Hossain, Md. Golzar; Tang, Yan-dong; Akter, Sharmin; Zheng, Chunfu (May 2022). "Roles of the polybasic furin cleavage site of spike protein in SARS-CoV-2 replication, pathogenesis, and host immune responses and vaccination". Journal of Medical Virology. 94 (5): 1815–1820. doi:10.1002/jmv.27539. PMID 34936124. S2CID 245430230.

- ^ To KK, Sridhar S, Chiu KH, Hung DL, Li X, Hung IF, Tam AR, Chung TW, Chan JF, Zhang AJ, Cheng VC, Yuen KY (December 2021). "Lessons learned 1 year after SARS-CoV-2 emergence leading to COVID-19 pandemic". Emerging Microbes & Infections. 10 (1): 507–535. doi:10.1080/22221751.2021.1898291. PMC 8006950. PMID 33666147.

- ^ a b Coutard B, Valle C, de Lamballerie X, Canard B, Seidah NG, Decroly E (April 2020). "The spike glycoprotein of the new coronavirus 2019-nCoV contains a furin-like cleavage site absent in CoV of the same clade". Antiviral Research. 176 (7): 104742. Bibcode:2020CBio...30E1346Z. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.022. PMC 7114094. PMID 32057769.

- ^ Zhang T, Wu Q, Zhang Z (April 2020). "Probable Pangolin Origin of SARS-CoV-2 Associated with the COVID-19 Outbreak". Current Biology. 30 (7): 1346–1351.e2. Bibcode:2020CBio...30E1346Z. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.022. PMC 7156161. PMID 32197085.

- ^ Wu Y, Zhao S (December 2020). "Furin cleavage sites naturally occur in coronaviruses". Stem Cell Research. 50: 102115. doi:10.1016/j.scr.2020.102115. PMC 7836551. PMID 33340798.

- ^ Worobey M, Pekar J, Larsen BB, Nelson MI, Hill V, Joy JB, Rambaut A, Suchard MA, Wertheim JO, Lemey P (October 2020). "The emergence of SARS-CoV-2 in Europe and North America". Science. 370 (6516): 564–570. doi:10.1126/science.abc8169. PMC 7810038. PMID 32912998.

- ^ "Initial genome release of novel coronavirus". Virological. 11 January 2020. Archived from the original on 12 January 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ a b Bedford T, Neher R, Hadfield N, Hodcroft E, Ilcisin M, Müller N. "Genomic analysis of nCoV spread: Situation report 2020-01-30". nextstrain.org. Archived from the original on 15 March 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ "Genomic epidemiology of novel coronavirus – Global subsampling". Nextstrain. 25 October 2021. Archived from the original on 20 April 2020. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ^ Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (April 2020). "The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2". Nature Microbiology. 5 (4): 536–544. doi:10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z. PMC 7095448. PMID 32123347.

- ^ Frutos, Roger; Pliez, Olivier; Gavotte, Laurent; Devaux, Christian A. (October 2021). "There is no "origin" to SARS-CoV-2". Environmental Research: 112173. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2021.112173. PMC 8493644. PMID 34626592.

- ^ Boni, Maciej F.; Lemey, Philippe; Jiang, Xiaowei; Lam, Tommy Tsan-Yuk; Perry, Blair W.; Castoe, Todd A.; Rambaut, Andrew; Robertson, David L. (November 2020). "Evolutionary origins of the SARS-CoV-2 sarbecovirus lineage responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic". Nature Microbiology. 5 (11): 1408–1417. doi:10.1038/s41564-020-0771-4. PMID 32724171. S2CID 220809302.

- ^ Pomorska-Mól, M.; Włodarek, J.; Gogulski, M.; Rybska, M. (July 2021). "Review: SARS-CoV-2 infection in farmed minks – an overview of current knowledge on occurrence, disease and epidemiology". Animal. 15 (7): 100272. doi:10.1016/j.animal.2021.100272. PMC 8195589. PMID 34126387.

- ^ Zhou, Hong; Chen, Xing; Hu, Tao; Li, Juan; Song, Hao; Liu, Yanran; Wang, Peihan; Liu, Di; Yang, Jing; Holmes, Edward C.; Hughes, Alice C.; Bi, Yuhai; Shi, Weifeng (June 2020). "A Novel Bat Coronavirus Closely Related to SARS-CoV-2 Contains Natural Insertions at the S1/S2 Cleavage Site of the Spike Protein". Current Biology. 30 (11): 2196–2203.e3. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2020.05.023. ISSN 1879-0445. PMC 7211627. PMID 32416074.

- ^ "Distance from Yunnan to Wuhan". Distancefromto.net. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ Wacharapluesadee, Supaporn; Tan, Chee Wah; Maneeorn, Patarapol; Duengkae, Prateep; Zhu, Feng; Joyjinda, Yutthana; Kaewpom, Thongchai; Chia, Wan Ni; Ampoot, Weenassarin; Lim, Beng Lee; Worachotsueptrakun, Kanthita; Chen, Vivian Chih-Wei; Sirichan, Nutthinee; Ruchisrisarod, Chanida; Rodpan, Apaporn; Noradechanon, Kirana; Phaichana, Thanawadee; Jantarat, Niran; Thongnumchaima, Boonchu; Tu, Changchun; Crameri, Gary; Stokes, Martha M.; Hemachudha, Thiravat; Wang, Lin-Fa (9 February 2021). "Evidence for SARS-CoV-2 related coronaviruses circulating in bats and pangolins in Southeast Asia". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 972. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12..972W. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-21240-1. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7873279. PMID 33563978.

- ^ a b Banerjee, Arinjay; Doxey, Andrew C.; Mossman, Karen; Irving, Aaron T. (1 March 2021). "Unraveling the Zoonotic Origin and Transmission of SARS-CoV-2". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 36 (3): 180–184. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2020.12.002. ISSN 0169-5347. PMC 7733689 glish. PMID 33384197.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmc=value (help) - ^ Frutos, Roger; Serra-Cobo, Jordi; Chen, Tianmu; Devaux, Christian A (1 October 2020). "COVID-19: Time to exonerate the pangolin from the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 to humans". Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 84: 104493. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104493. ISSN 1567-1348. PMC 7405773. PMID 32768565.

- ^ "Can Frozen Food Spread The Coronavirus?". NPR. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ "Origins of the COVID-19 Pandemic". Congressional Research Service. 11 June 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ a b Lardieri, Alexa (9 February 2021). ""WHO: 'Extremely Unlikely' Coronavirus Came From Lab in China"". US News. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ a b Lawton, Graham (June 2021). "Did covid-19 come from a lab?". New Scientist. 250 (3337): 10–11. doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(21)00938-6. PMC 8177866. PMID 34108789.

- ^ Yang, Yang; et al. (10 June 2015). "Two Mutations Were Critical for Bat-to-Human Transmission of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus". Journal of Virology. 89 (17): 9119–9123. doi:10.1128/JVI.01279-15. PMC 4524054. PMID 26063432.

- ^ Menachery, Vineet D; et al. (9 November 2015). "A SARS-like cluster of circulating bat coronaviruses shows potential for human emergence". Nature Medicine. 21 (12): 1508–1513. doi:10.1038/nm.3985. PMC 4797993. PMID 26552008.

- ^ Hakim, Mohamad S. (2021). "SARS-CoV-2, Covid-19, and the debunking of conspiracy theories". Reviews in Medical Virology. 31 (6): e2222. doi:10.1002/rmv.2222. PMC 7995093. PMID 33586302.

- ^ "The 'Occam's Razor Argument' Has Not Shifted in Favor of a Lab Leak". Snopes.com. Snopes. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ Maxmen, Amy (27 May 2021). "Divisive COVID 'lab leak' debate prompts dire warnings from researchers". Nature. 594 (7861): 15–16. Bibcode:2021Natur.594...15M. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-01383-3. PMID 34045757. S2CID 235232290.

- ^ a b Calisher, Charles H; Carroll, Dennis; Colwell, Rita; Corley, Ronald B; Daszak, Peter; Drosten, Christian; Enjuanes, Luis; Farrar, Jeremy; Field, Hume; Golding, Josie; Gorbalenya, Alexander E; Haagmans, Bart; Hughes, James M; Keusch, Gerald T; Lam, Sai Kit; Lubroth, Juan; Mackenzie, John S; Madoff, Larry; Mazet, Jonna Keener; Perlman, Stanley M; Poon, Leo; Saif, Linda; Subbarao, Kanta; Turner, Michael (July 2021). "Science, not speculation, is essential to determine how SARS-CoV-2 reached humans". The Lancet. 398 (10296): 209–211. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01419-7. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 8257054 glish. PMID 34237296.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmc=value (help) - ^ Rabi, Firas A.; Al Zoubi, Mazhar S.; Kasasbeh, Ghena A.; Salameh, Dunia M.; Al-Nasser, Amjad D. (20 March 2020). "SARS-CoV-2 and Coronavirus Disease 2019: What We Know So Far". Pathogens. 9 (3): 231. doi:10.3390/pathogens9030231. PMC 7157541. PMID 32245083.

- ^ Beyerstein, Lindsay (29 June 2021). "The Case Against the Covid-19 Lab Leak Theory". The New Republic. Retrieved 2 July 2021. "When you work with this particular virus in the lab, it becomes less capable of being a human pathogen and becomes more of a cell culture adapted virus"..."So that suggests, again, that it's unlikely that this virus, if it were being passaged extensively in cell culture, would jump out of cell culture into people and start a pandemic." - Angella Rasmussen

- ^ Hayes, Polly. "Here's how scientists know the coronavirus came from bats and wasn't made in a lab". The Conversation. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ Paraskevis, D.; Kostaki, E.G.; Magiorkinis, G.; Panayiotakopoulos, G.; Sourvinos, G.; Tsiodras, S. (April 2020). "Full-genome evolutionary analysis of the novel corona virus (2019-nCoV) rejects the hypothesis of emergence as a result of a recent recombination event". Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 79: 104212. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104212. PMC 7106301. PMID 32004758.

- ^ Calisher, Charles; Carroll, Dennis; Colwell, Rita; Corley, Ronald B.; Daszak, Peter; Drosten, Christian; Enjuanes, Luis; Farrar, Jeremy; Field, Hume; Golding, Josie; Gorbalenya, Alexander; Haagmans, Bart; Hughes, James M.; Karesh, William B.; Keusch, Gerald T.; Lam, Sai Kit; Lubroth, Juan; Mackenzie, John S.; Madoff, Larry; Mazet, Jonna; Palese, Peter; Perlman, Stanley; Poon, Leo; Roizman, Bernard; Saif, Linda; Subbarao, Kanta; Turner, Mike (7 March 2020). "Statement in support of the scientists, public health professionals, and medical professionals of China combatting COVID-19". The Lancet. 395 (10226): e42–e43. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30418-9. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7159294 glish. PMID 32087122.

{{cite journal}}: Check|pmc=value (help) - ^ Lu, Roujian; Zhao, Xiang; Li, Juan; Niu, Peihua; Yang, Bo; Wu, Honglong; Wang, Wenling; Song, Hao; Huang, Baoying; Zhu, Na; Bi, Yuhai; Ma, Xuejun; Zhan, Faxian; Wang, Liang; Hu, Tao; Zhou, Hong; Hu, Zhenhong; Zhou, Weimin; Zhao, Li; Chen, Jing; Meng, Yao; Wang, Ji; Lin, Yang; Yuan, Jianying; Xie, Zhihao; Ma, Jinmin; Liu, William J; Wang, Dayan; Xu, Wenbo; Holmes, Edward C; Gao, George F; Wu, Guizhen; Chen, Weijun; Shi, Weifeng; Tan, Wenjie (February 2020). "Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding". The Lancet. 395 (10224): 565–574. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30251-8. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7159086. PMID 32007145.

- ^ Zhou, Hong; Ji, Jingkai; Chen, Xing; Bi, Yuhai; Li, Juan; Wang, Qihui; Hu, Tao; Song, Hao; Zhao, Runchu; Chen, Yanhua; Cui, Mingxue; Zhang, Yanyan; Hughes, Alice C.; Holmes, Edward C.; Shi, Weifeng (June 2021). "Identification of novel bat coronaviruses sheds light on the evolutionary origins of SARS-CoV-2 and related viruses". Cell. 184 (17): 4380–4391.e14. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.06.008. ISSN 0092-8674. PMC 8188299. PMID 34147139. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ York, Ashley (18 June 2021). "Searching for relatives of SARS-CoV-2 in bats". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 19 (8): 482. doi:10.1038/s41579-021-00595-8. ISSN 1740-1534. PMC 8212067. PMID 34145421.

- ^ "Wuhan, U.S. Scientists Planned to Make Coronaviruses, Documents Leaked by DRASTIC Show". Newsweek. 8 October 2021.

- ^ "In Major Shift, NIH Admits Funding Risky Virus Research in Wuhan". Vanity Fair. 22 October 2021.

- ^ "NIH says grantee failed to report experiment in Wuhan that created a bat virus that made mice sicker". Science. 21 October 2021.

- ^ "Fauci stands by gain-of-function research denials, defends collaboration with Wuhan lab". The Denver Gazette. 24 October 2021.

- ^ "NIH Presses U.S. Nonprofit for Information on Wuhan Virology Lab". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- ^ "The WHO's Chief Says It Was Premature To Rule Out A Lab Leak As The Pandemic's Origin". NPR. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ Pinghui, Zhuang (22 July 2021). "China rejects WHO plan for study into Covid-19 origin". CNBC. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ "WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the Member State Information Session on Origins," WHO, 16 July 2021. Retrieved 26 July 2021.

- ^ "China Has Rejected A WHO Plan For Further Investigation Into The Origins Of COVID-19," AP, 22 July 2021. Retrieved 26 July 2021.

- ^ Buckley, Chris (22 July 2021). "China denounces the W.H.O.'s call for another look at the Wuhan lab as 'shocking' and 'arrogant.'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ Schafer, Bret. "China Fires Back at Biden with Conspiracy Theories About Maryland Lab". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 26 July 2021.

- ^ "WHO | Pneumonia of unknown cause – China". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 18 April 2020. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ Areddy, James T. (26 May 2020). "China Rules Out Animal Market and Lab as Coronavirus Origin". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 17 February 2021. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ Mackenzie, John S.; Smith, David W. (17 March 2020). "COVID-19: a novel zoonotic disease caused by a coronavirus from China: what we know and what we don't". Microbiology Australia. 41: 45. doi:10.1071/MA20013. ISSN 1324-4272. PMC 7086482. PMID 32226946.

- ^ Gan, Nectar; Hu, Caitlin; Watson, Ivan (12 April 2020). "China imposes restrictions on research into origins of coronavirus". CNN. Archived from the original on 17 January 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ Kang, Dake; Cheng, Maria; Mcneil, Sam (30 December 2020). "China clamps down in hidden hunt for coronavirus origins". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ Manson, Katrina; Yu, Sun (26 April 2020). "US and Chinese researchers team up for hunt into Covid origins". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 14 November 2020. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ^ "OSTP Coronavirus Request to NASEM" (PDF). nationalacademies.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ Gittleson, Ben (6 February 2020). "White House asks scientists to investigate origins of coronavirus". ABC News. Archived from the original on 8 February 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ Campbell, Josh; Atwood, Kylie; Perez, Evan (16 April 2020). "US explores possibility that coronavirus spread started in Chinese lab, not a market". CNN. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ Dilanian, Ken; Kube, Courtney (16 April 2020). "U.S. intel community examining whether coronavirus emerged accidentally from a Chinese lab". NBC News. Archived from the original on 16 April 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2021.