Havana Plan Piloto: Difference between revisions

→Palacio de las palmas: added paragraph: "The Cuban government owned the site..." |

|||

| Line 228: | Line 228: | ||

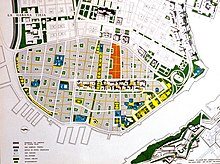

[[File:Plan piloto de la habana.2 1956.jpg|thumb|right|Plan Piloto de la Habana. 1956. Proposed presidential palace]] |

[[File:Plan piloto de la habana.2 1956.jpg|thumb|right|Plan Piloto de la Habana. 1956. Proposed presidential palace]] |

||

[[File:Palacio de los Capitanes Generales. Havana, Cuba Floor Plan.jpg|thumb|right|In the design of the new presidential palace, Sert considered several courtyards of historical structures in Havana including the [[Palacio de los Capitanes Generales]]]] |

[[File:Palacio de los Capitanes Generales. Havana, Cuba Floor Plan.jpg|thumb|right|In the design of the new presidential palace, Sert considered several courtyards of historical structures in Havana including the [[Palacio de los Capitanes Generales]]]] |

||

The Cuban government owned the site the future presidential palace was going to be, it was a large piece of land between two fortresses, El Castillo del Morro and La Cabaña; thus, the proposed site had a prominent topography, did not require expropriation, and had historic relevance. Wiener was advised that a competition would be held for the design of a new presidential palace. Competitors included Wells Coates, Franco Albini, and the firm of Welton Beckett and Associates, Le Corbusier and Oscar Niemeyer would also be invited. Mario Romañach indicated to Wiener his desire to work on the project and, along with Town Planning Associates, was added to the list. Soon after the initial announcement, the idea of a competition was abandoned, Town Planning Associates was given the commission outright as well as to Mario Romañach and Gabriela Menéndez. Several people have noted that the future location of the palace on the undeveloped east side of the bay in conjunction with the construction of new tunnel would encourage development of Havana toward the east, maintaining Habana Vieja as a vital center and discourage westward expansion. With the commission for the presidential palace secured, Sert and Romañach become the primary designers of the project, Félix Candela was to be the structural engineer and Hideo Sasaki the landscape architect. Sert and Romañach commenced their design the following year developing the project between the fall of 1956 and the summer of 1957 after initial plans and a model were exhibited for Batista and his cabinet in the Salón de los Espejos of the [[Museum of the Revolution (Cuba)|existing presidential palace]].<ref name="minnesota"/> |

|||

The Plan Piloto included the project by Romañach, Gabriela Menéndez, Mercedes Diaz and [[Josep Lluís Sert]] for the new [[Museum of the Revolution (Cuba)|Presidential Palace]] which would have been located near the Castle of San Carlos de [[La Cabaña]] and the [[Morro Castle (Havana)|Castle of the Three Kings of El Morro]]. The Presidential palace project was never executed. Photo of project maquette. |

|||

The designers of the Pilot Plan contemplated the construction of a monumental Presidential Palace that was conceived as a large residential and civic complex with a yacht dock with private access to the bay of Havana. The presidential palace was the center of this ambitious complex with several ministries, two large civic plazas, a Marti park, an oceanography museum and an aquarium.<ref name="fracasados">{{cite web|url=http://carlosbua.com/los-proyectos-inconclusos-o-fracasados-de-fidel-castro/|title=Los proyectos inconclusos o fracasados de Fidel Castro|access-date=2020-01-18}}</ref> |

The Plan Piloto then included the project by Romañach, Gabriela Menéndez, Mercedes Diaz and [[Josep Lluís Sert]] for the new [[Museum of the Revolution (Cuba)|Presidential Palace]] which would have been located near the Castle of San Carlos de [[La Cabaña]] and the [[Morro Castle (Havana)|Castle of the Three Kings of El Morro]]. The Presidential palace project was never executed. Photo of project maquette.The designers of the Pilot Plan contemplated the construction of a monumental Presidential Palace that was conceived as a large residential and civic complex with a yacht dock with private access to the bay of Havana. The presidential palace was the center of this ambitious complex with several ministries, two large civic plazas, a Marti park, an oceanography museum and an aquarium.<ref name="fracasados">{{cite web|url=http://carlosbua.com/los-proyectos-inconclusos-o-fracasados-de-fidel-castro/|title=Los proyectos inconclusos o fracasados de Fidel Castro|access-date=2020-01-18}}</ref> |

||

The Palacio de las Palmas (Palace of the Palms) also accommodated in its program the executive branch of the Batista government, including the offices of the ministry, facilities for the press, reception halls, and the private residence for Batista and his family. "The compulsion to construct a representation of cubanidad produced a representational crisis in both the political and aesthetic registers of the project. The architecture not only symbolizes nationhood and citizenship but contributes to the production of civic behavior."<ref name="minnesota"/> |

The Palacio de las Palmas (Palace of the Palms) also accommodated in its program the executive branch of the Batista government, including the offices of the ministry, facilities for the press, reception halls, and the private residence for Batista and his family. "The compulsion to construct a representation of cubanidad produced a representational crisis in both the political and aesthetic registers of the project. The architecture not only symbolizes nationhood and citizenship but contributes to the production of civic behavior."<ref name="minnesota"/> |

||

Revision as of 15:33, 21 January 2020

| Havana Plan Piloto | |

|---|---|

Havana Plan Piloto | |

| |

| General information | |

| Status | Abandoned |

| Architectural style | International |

| Classification | Urban |

| Location | City of Havana |

| Town or city | |

| Country | |

| Coordinates | 23°06′49″N 82°22′00″E / 23.1136°N 82.3666°E |

| Height | |

| Architectural | Modern |

| Technical details | |

| Size | 781.58 km2 (301.77 sq mi) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Josep Lluis Sert, Paul Lester Wiener, Mario Romañach |

| Developer | Junta Nacional de Planificacion de Cuba |

The Havana Plan Piloto was a 1955-1958 urban proposal by Catalan architect Josep Lluis Sert and Paul Lester Wiener of Town Planning Associates seeking to combine "architecture, planning, and law" in order to modernize the city, and in the process erase all vestiges of the 16th century city.[1]

History

Source: Havana

The 20th century began with Cuba under occupation by the United States.[2] The US occupation officially ended when Tomás Estrada Palma, first president of Cuba, took office on 20 May 1902.

During the Republican Period, from 1902 to 1959, the city saw a new era of development. Cuba recovered from the devastation of war to become a well-off country, with the third largest middle class in the hemisphere. Apartment buildings to accommodate the new middle class,and mansions for the well to do, were built at a fast pace.

Numerous luxury hotels, casinos and nightclubs were constructed during the 1930s to serve Havana's burgeoning tourist industry, which greatly benefited by the U.S. prohibition on alcohol from 1920 to 1933. In the 1930s, organized crime characters were not unaware of Havana's nightclub and casino life, and they made their inroads in the city. Santo Trafficante Jr. took the roulette wheel at the Sans Souci Casino, Meyer Lansky directed the Hotel Habana Riviera, with Lucky Luciano at the Hotel Nacional Casino. At the time, Havana became an exotic capital of appeal and numerous activities ranging from marinas, grand prix car racing, musical shows, and parks. It was also the favorite destination of sex tourism and gambling.[3]: 127 [a]

Corruption

Cuba had suffered from widespread and rampant corruption since the establishment of the Republic in 1902. The book Corruption in Cuba states that public ownership resulted in "a lack of identifiable ownership and widespread misuse and theft of state resources... when given opportunity, few citizens hesitate to steal from the government."[4] Furthermore, the complex relationship between governmental and economic institutions makes them especially "prone to corruption."[5]

The question of what causes corruption in Cuba presently and historically continues to be discussed and debated by scholars. Jules R. Benjamin suggests that Cuba's corrupt politics were a product of the colonial heritage of Cuban politics and the financial aid provided by the United States that favoured international sugar prices in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[6] Following the Second World War, the level of corruption in Cuba, among many other Latin American and Caribbean countries, was said to have risen significantly.[7] Some scholars, such as Eduardo Sáenz Rovner, attribute this to North America's increased involvement in Cuba after the First World War as it isolated Cuban workers.[7] Cubans were excluded from a large sector of the economy and unable to participate in managerial roles that were taken over by United States employers.[7] Along similar lines, Louis A. Pérez has written that “World War Two created new opportunities for Cuban economic development, few of which, however, were fully realized. Funds were used irrationally. Corruption and graft increased and contributed in no small part to missed opportunities, but so did mismanagement and miscalculation.”[8]

Transparency International's 2017 Corruption Perception Index (CPI) gave Cuba a score of 47/100, where 0 indicates that a country is very corrupt and 100 indicates that it is very clean. Cuba ranks 62nd out of 180 countries in terms of corruption perception, which is an increase of 2 places since last years' CPI score in 2016.[9]

Havana Conference

The Havana Conference of 1946 was a historic meeting of United States Mafia and Cosa Nostra leaders in Havana, Cuba.[b] Supposedly arranged by Charles "Lucky" Luciano, the conference was held to discuss important mob policies, rules, and business interests. The Havana Conference was attended by delegations representing crime families throughout the United States. The conference was held during the week of December 22, at the Hotel Nacional. The Havana Conference is considered to have been the most important mob summit since the Atlantic City Conference of 1929. Decisions made in Havana resonated throughout US crime families during the ensuing decades. Havana achieved the title of being the Latin American city with the biggest middle class population per capita, simultaneously accompanied by gambling and corruption where gangsters and stars were known to mix socially. During this era, Havana was generally producing more revenue than Las Vegas, Nevada, whose boom as a tourist destination began only after Havana's casinos closed in 1959. In 1958, about 300,000 American tourists visited the city.[11]

In December 1946, the Havana Conference started as planned. To welcome Luciano back from exile and acknowledge his continued authority within the mob, all the conference invitees brought Luciano cash envelopes. These "Christmas Presents" totalled more than $200,000. At the first night dinner hosted by Meyer Lansky, Frank Costello, and Joe Adonis, Luciano was presented with the money. The official cover story for the Havana Conference was that the mobsters were attending a gala party with Frank Sinatra as the entertainment. Sinatra flew to Havana with Al Capone cousins, Charles Fischetti, and Rocco Fischetti from Chicago. Joseph "Joe Fish" Fischetti, an old Sinatra acquaintance, acted as Sinatra's chaperone and bodyguard. Charlie and Rocco Fischetti delivered a suitcase containing $2 million to Luciano, his share of the U.S. rackets he still controlled.[11]

The most pressing items on the conference agenda were the leadership and authority within the New York mafia, the mob-controlled Havana casino interests, the narcotics operations, and the West Coast operations of Benjamin "Bugsy" Siegel, especially the new Flamingo Hotel and casino in Las Vegas. Luciano, absent from the American underworld scene for several months, was especially concerned with the situation in New York. Boss Vito Genovese had returned to New York from exile in Italy and was not content with assuming a minor role in the organization.[11]

Delegates

The Havana Conference convened on December 20, 1946.[10] Delegates were present representing New York City, New Jersey, Buffalo, Chicago, New Orleans and Florida, with the largest delegation of bosses from the New York-New Jersey area. Several major bosses from the Jewish Syndicate were at the conference to discuss joint La Cosa Nostra-Jewish Syndicate business. According to conference rules, the Jewish delegates could not vote on Cosa Nostra rules or policies; however, the Jewish crime bosses were allowed input on any joint business ventures, such as the Flamingo Hotel.

Luciano opened the Havana Conference by discussing a topic that would greatly affect his authority within the American Mafia; the position of "capo di tutti capi" or "boss of all bosses". The last official boss of all bosses had been Salvatore Maranzano, who was murdered in September 1931. By the end of 1931, Luciano had eliminated this top position and re-organized the Italian mafia into "La Cosa Nostra", or "This Thing of Ours". A board of directors, commonly called the "Commission", had been formed to oversee criminal activities, control rules, and set policies. La Cosa Nostra thus became the top criminal organization within the National Crime Syndicate.

Now Luciano could easily have declared himself as Maranzano's heir in 1932; instead, Luciano decided to exercise control behind the scenes. This arrangement had worked until Vito Genovese's return from Italy. Officially, Genovese was now just a caporegime; however, he had made it clear that he intended to take control of the Luciano crime family. Since Luciano's deportation in 1946, Luciano ally Frank Costello had been the acting boss of the Luciano family. As a result, tensions between the Costello and Genovese factions had started to fester. Luciano had no intention of stepping down as family boss; he had to do something about Genovese. Luciano also realized that Genovese threatened his overall authority and influence within the American mafia, probably with support from other crime bosses. Therefore, Luciano decided to resurrect the boss of all bosses position and claim it for himself. He hoped the other bosses would support him, either by officially affirming the title or at least by acknowledging that he was still "First Amongst Equals".

At the conference, Luciano allegedly presented the motion to retain his position as the top boss in La Cosa Nostra. Then Luciano ally, Albert "The Mad Hatter" Anastasia seconded the motion. Anastasia voted with Luciano because he felt threatened by Genovese's attempts to muscle in on his waterfront rackets. Checkmated by the Luciano-Costello-Anastasia alliance, Genovese was forced to swallow his ambitions and plan for the future. To further embarrass Genovese, Luciano encouraged Anastasia and Genovese to settle their differences and shake hands in front of the other bosses. This symbolic gesture was meant to prevent another bloody gang war such as the Castellammarese War of 1930–1931. With Luciano solidifying his personal position and squashing Genovese's ambition for now, Luciano brought up discussion of the mob's narcotics operations in the United States.

Narcotics trade

One of the key topics at the Havana Conference, was the global narcotics trade and the mob's operations in the United States. A longstanding myth has been the supposed refusal of Luciano and the Cosa Nostra to deal in narcotics. Only a few bosses such as Frank Costello and the other bosses who controlled lucrative gambling empires opposed narcotics. The anti-drug faction believed that the Cosa Nostra did not need narcotics profits, that narcotics brought unwanted law enforcement and media attention, and that the general public considered it to be a very harmful activity (unlike gambling). The pro-drug faction said that narcotics were far more profitable than any other illegal activity. Furthermore, if the Cosa Nostra ignored the drug trade, other criminal organizations would jump in and eventually diminish the Cosa Nostra's power and influence.

Luciano himself had a long involvement in the drug trade, starting as a smalltime street dealer in the late 1910s. In 1928, after the murder of Arnold "The Big Bankroll" Rothstein, Luciano and Louis "Lepke" Buchalter took over Rothstein's large drug importation operation. Since the 1920s, La Cosa Nostra had been involved in drug importation (heroin, cocaine, and marijuana) into North America. In the 1930s, the organization started transporting narcotics from the East Asia Golden Triangle and South America to Cuba and into Florida. The American mob's longtime association with the government of Cuba concerning gambling interests such as casinos along with their legitimate business investments on the Caribbean island put them in a position to use their political and underworld connections to make Cuba one of their narcotics importation layovers or smuggling points where the drugs could be stored and then placed on sea vessels before they continued on to Canada and United States via Montreal and Florida among the ports used by Luciano's associates.[11]

With Luciano's deportation to Italy, he now had the opportunity to import heroin from North Africa via Italy and Cuba into the US and Canada. Luciano made connections with Sicily's biggest bosses such as Don Calogero "Calo" Vizzini of Villalba who assisted the Allies' invasion of Sicily and had the greatest political connections of all the Sicilian bosses. Also, Don Pasquale Ania, a powerful boss in Palermo who had connections to legitimate pharmaceutical companies because large-scale heroin manufacturing in Italy was legal at the time.

During the Havana Conference, Luciano detailed the proposed drugs network to the bosses. After arriving in Cuba from North Africa, the mob would ship the narcotics to US ports that it controlled, primarily New York City, New Orleans, and Tampa. The narcotics shipped to the New York docks would be overseen by the Luciano crime family (later the Genovese) and the Mangano crime family (later the Gambino). In New Orleans, the operation would be overseen by the Marcello crime family, led by Carlos "Little Man" Marcello. In Tampa, the narcotics shipments would be overseen by the Trafficante crime family led by Santo Trafficante, Jr. The Havana Convention delegates voted to approve the plan.[11]

Plan piloto

It is within this climate of mob involvement in Havana, that in 1956 Fulgencio Batista hires the Catalan architect Josep Lluis Sert. Sert had worked with Le Corbusier in his atelier on 35 Rue de Sevres in Paris, and elaborated the Havana Master Plan in collaboration with Paul Lester Wiener and Paul Schulz. Architects that also collaborated on the Plan Piloto were Nicolás Arroyo, Minister of Public Works of the Batista government, and the architects Gabriela Menéndez and Mario Romañach, among others.[12]

The Plan Piloto focused on two master plan elements as defined by José Luis Sert: (a) the division of the city into various sectors, and (b) the intallation of a classified road system. This determination of sectors and roads was based on two prerequisites: on the fixing of limits of the greater metropolitan area and the analysis of land use within these limits. The metropolitan limits of area was to be used as the basis for new legislative requirements, and argued that any such legislation would stipulate that the city authorities provided utilities only for the repartos[c] even though the people of the repartos had not been consulted during the planning stages.[13] Concurrently with the definition of the city limits, the Oficina del Plan Regulador de la Habana (OPRH) compiled an existing land-use map of the metropolitan area. This information would be applied to the work of the Plan Piloto, under Romañach.

JNP

Junta Nacional de Planificacion de Cuba (JNP)[14] and its consultants were agents for Batista’s administration; the plan for the proposed East Havana or the policy for the Malecón ensured continued economic pressure for urban development and speculation with which the JNP would regulate. The economic atmosphere of the Batista government was permissive as was the social atmosphere; real-estate speculation was promoted and encouraged with investors adding new hotels, casinos, condominiums, and department stores to the city’s fabric. It was in this context that the provision of land for construction were a pressing financial motive for Batista’s administration; Batista's government depended on an increasing flow of extraneous capital into the country. The architects of the JNP were cognizant this overwhelming sway of economic growth, Wiener apparently spent some spare hours in Havana evaluating prospective building sites for the New York developer Paul Tishman. The work of the JNP framed its sights within a political environment, directing technicians to mediate between state and city rather than local or foreign investors, businessmen, or the public who were their beneficiaries. The Plan Piloto was both an instrument of complicity, insofar as it would have accommodated and even assisted the unmitigated financial speculations in that it would have defined and guided much of the physical outcome of that speculation in advance.[13]: 149

Metropolitan area

The greater metropolitan area of Havana would have been affected by the Plan Piloto; it included suggestions for the development of unbuilt areas and included the distribution of the four functions as outlined in the Athens Charter and as suggested by Le Corbusier's manifesto for planning which was published in 1943 for the Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne, (CIAM) and resulting in the [[Athens Charter}The Functional City]], this was achieved through the principles of modernist zoning.[15]

The most significant component of the Plan Piloto was a comprehensive transportation system for Havana. The aim of the Plan was to contain the different efforts of the various historical periods within the city through a planning conceptual order. The Sert and Wiener Plan focused on providing improved accessibility for traffic to the heart of the old city. "Two major north-south dual carriageways were planned to cut through the center of Old Havana on Calle Cuba and Calle Habana streets. A further dual carriageway was to cut through the center on an east-west axis along Calle Muralla, and alternate streets on the city grid in both directions were to be widened. In true ‘tabula rasa’ fashion the city blocks in the entire area enclosed by these dual carriageways were to be demolished and replaced with a series of classic modernist slab blocks."[15] The remaining blocks were to be hollowed out in order to improve automobile access and parking, demolition would have been required to accommodate the widening of other streets. The Pilot Plan would have resulted in the division of the old city into four quarters separated by major traffic lanes, widespread demolition of historic buildings and with the character of remaining city blocks being fundamentally altered.[15]

New legislation

New legislation would specify a process by which the consent of the existing municipal government would be required for any new reparto. A process that would allow the imposition of certain design criteria, including provisions for new utilities, open space rations, community uses, densities, and building types. were aware that their proposal required considerable renovation of existing legal structures because the area they defined as metropolitan Havana was in fact composed of different independent municipalities. These, Sert suggested, could establish a joint authority that would enact measures to limit the location and design of repartos according to the principles proposed by the JNP and Town Planning Associates.[16] were aware that their proposal required considerable renovation of existing legal structures because the area they defined as metropolitan Havana was in fact composed of different independent municipalities. These, Sert suggested, could establish a joint authority that would enact measures to limit the location and design of repartos according to the principles proposed by the JNP and Town Planning Associates.[17]

Mario Romañach

With the definition of the city limits, the Oficina del Plan Regulador de la Habana (OPRH) compiled a land-use map of the metropolitan area of Havana; information was applied to the work of the Plan Piloto. Under Mario Romañach; [d] such information indicated that the city was perceived as a regional economic and social urban entity. The color codes marked the residential, commercial, industrial, and recreational uses throughout the city thus producing a tapestry that highlighted how certain functions, clustered in large blocks, or urban corridors, or isolated within other functions, legislation and design could be oriented toward segregating certain functions, such as the industrial uses; and juxtaposing others, such as the residential and the recreational uses.[13]: 141

Mario Romañach[e]collaborated on the Plan Piloto under the auspices of the Minister of Public Works, and the National Planning Board of Cuba between 1955 and 1958, in the development of the Plan Piloto for Havana.[18] The Town Planning Associates, a consulting firm from New York City, led by the Catalan architect Josep Lluís Sert, and its partners Paul Lester Wiener and Paul Schulz, was hired by the Minister of Public Works with the intention of guiding the development of the continuous growth of the city of Havana during the next decade.[15]

Artificial island

The idea of building an artificial island in front of the Malecon in Havana first appeared in the Plan Piloto of 1956, it's aim was to make Havana the most modern city in the Americas particularly in giving it greater character of a capital city and tourist center, and increase tourist attraction and thus sources of income. In the decade of the 50s, Havana was a hotbed of American tourism and the Plan Piloto sought to promote Batista's government and various civic institutions which had resulted in the construction of major hotels like the Capri, the Havana Hilton, the the Riviera, and the Rosita de Hornedo, among other hotels, which would responded to the increased demand to the tourism from the north. The Plan sought to strengthen future tourist development planned not only for Havana, but for Varadero, Cojímar and the Isle of Pines. The developmenmt plans were closely linked to the penetration of mafia capital from the United States. Meyer Lansky and Santo Trafficante came to invest in Cuba with the Havana Riviera and Capri hotels, respectively, as part of a strategy to turn Havana into a Las Vegas in the Caribbean.[19]

There has been much talk about this, especially because of President Batista's agreements with the Italian-American mafia to create hundreds of hotels and casinos that would make Havana the Monte Carlo of America, but only older residents of Havana may remember the idea of building an artificial island just in front of the wall of the boardwalk and that would comprise the space between Galiano and Belascoaín streets, where it would be accessed, just one of the areas that are most flooded in the face of the occurrence of natural phenomena such as cyclones, cold fronts or extratropical casualties.[19]

Critique

Rafael Fornés in Studies of Havana writes a critique of the Plan Piloto:

It also proposed a rectangular artificial island on the sea of 2,500 feet long by 100 wide[f] connecting it to the mainland with the extension of two Havana stoas; the porticoes of Galiano and Belascoaín. Destroyed the visuals of the fifteen blocks of the historic Havana Malecon. The most brutal part was destined for the colonial Old Havana. It was divided into four sectors by a network of unnecessary highways. Avenida del Puerto and Muralla and Habana streets became important fast transit routes. Four hundred years of history and more than 900 historic buildings would disappear by decree. The ensembles of the Plaza de la Catedral and de Armas timidly survived; and the convents of San Francisco, Belén, Merced and Santa Clara exclusively. Starting from the latter and along the length and breadth of Havana, Cuba and Aguiar streets, the banking area and offices and shops were located by building anonymous high-rise buildings. All the historical fabric and its varied and sophisticated types of patios were travestied in cul-de-sacs with trees to mask the parking lots of cars.[12]

Palacio de las palmas

The Cuban government owned the site the future presidential palace was going to be, it was a large piece of land between two fortresses, El Castillo del Morro and La Cabaña; thus, the proposed site had a prominent topography, did not require expropriation, and had historic relevance. Wiener was advised that a competition would be held for the design of a new presidential palace. Competitors included Wells Coates, Franco Albini, and the firm of Welton Beckett and Associates, Le Corbusier and Oscar Niemeyer would also be invited. Mario Romañach indicated to Wiener his desire to work on the project and, along with Town Planning Associates, was added to the list. Soon after the initial announcement, the idea of a competition was abandoned, Town Planning Associates was given the commission outright as well as to Mario Romañach and Gabriela Menéndez. Several people have noted that the future location of the palace on the undeveloped east side of the bay in conjunction with the construction of new tunnel would encourage development of Havana toward the east, maintaining Habana Vieja as a vital center and discourage westward expansion. With the commission for the presidential palace secured, Sert and Romañach become the primary designers of the project, Félix Candela was to be the structural engineer and Hideo Sasaki the landscape architect. Sert and Romañach commenced their design the following year developing the project between the fall of 1956 and the summer of 1957 after initial plans and a model were exhibited for Batista and his cabinet in the Salón de los Espejos of the existing presidential palace.[13]

The Plan Piloto then included the project by Romañach, Gabriela Menéndez, Mercedes Diaz and Josep Lluís Sert for the new Presidential Palace which would have been located near the Castle of San Carlos de La Cabaña and the Castle of the Three Kings of El Morro. The Presidential palace project was never executed. Photo of project maquette.The designers of the Pilot Plan contemplated the construction of a monumental Presidential Palace that was conceived as a large residential and civic complex with a yacht dock with private access to the bay of Havana. The presidential palace was the center of this ambitious complex with several ministries, two large civic plazas, a Marti park, an oceanography museum and an aquarium.[19]

The Palacio de las Palmas (Palace of the Palms) also accommodated in its program the executive branch of the Batista government, including the offices of the ministry, facilities for the press, reception halls, and the private residence for Batista and his family. "The compulsion to construct a representation of cubanidad produced a representational crisis in both the political and aesthetic registers of the project. The architecture not only symbolizes nationhood and citizenship but contributes to the production of civic behavior."[13]

The architects were thus called upon to express "cubanidad" with a symbol worthy of the name they responded with a large canopy roof of individual parasols intended to resemble royal palm trees, elements that Batista called the “most typical of Cuba."[20][g]

The patio of the Palacio de las Palmas was recognized by Sert as a feature of several historical structures in Havana including the Palacio de Aldama,[1][h] the Palacio de los Capitanes Generales, and the existing presidential palace.[13]

Jean Labatut of Princeton University provided a sketch from East Havana of an early proposal for the tunnel entrance under Havana harbor showing the skyline including the dome of the Capitolio Nacional.[21][13]: 149

See also

- Havana Vieja

- Centro Habana

- Malecon

- Havana Tunnel

- Barrio de San Lázaro

- Josep Lluís Sert

- Mario Romañach

- Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne

- Le Corbusier

Notes

- ^ "Batista and Lansky formed a renowned friendship and business relationship that lasted for a decade. During a stay at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York in the late 1940s, it was mutually agreed upon that, in exchange for kickbacks, Batista would offer Lansky and the Mafia control of Havana's racetracks and casinos. Batista would open Havana to large scale gambling, and his government would match, dollar for dollar, any hotel investment over $1 million, which would include a casino license. Lansky would place himself at the center of Cuba's gambling operations. He immediately called on his associates to hold a summit in Havana." Source: Wikipedia Meyer Lansky

- ^ List of the organized crime figures who attended the Havana Conference on December 20, 1946 at the Hotel Nacional in Havana, Cuba.

Hosts

- Charlie "Lucky" Luciano,[10] former Luciano family boss, former chairman, co-founder and member of the Commission. Luciano was living in Naples, Italy. After the meeting he was named America's boss of bosses.

- Meyer "The Little Man" Lansky,[10] Jewish Syndicate boss, a top financial and gambling operations advisor for the Italian mafia in America and casino operations front man (Las Vegas, Cuba, Bahamas).

New York-New Jersey Delegation

- Frank "The Prime Minister" Costello, Luciano family boss, Commission member.

- Gaurino "Willie Moore" Moretti, Luciano Family underboss.

- Vito "Don Vito" Genovese, Luciano Family caporegime and future boss.

- Giuseppe "Joe Adonis" Doto, Luciano Family caporegime.

- Anthony "Little Augie Pisano" Carfano, Luciano Family caporegime.

- Michele "Big Mike" Miranda, Luciano Family caporegime and future consigliere.

- Albert "The Mad Hatter" Anastasia, Mangano Family underboss and future boss.

- Joseph "Joe Bananas" Bonanno, Bonanno Family boss, charter Commission member.

- Gaetano "Tommy Brown" Lucchese, Gagliano Family underboss and future boss.

- Giuseppe "The Old Man" Profaci, Profaci Family boss, charter Commission member.

- Giuseppe "Fat Joe" Magliocco, Profaci Family underboss.

Chicago Delegation

- Anthony "Joe Batters" Accardo, Chicago Outfit boss, Commission member.

- Charles "Trigger Happy" Fischetti, Chicago Outfit consigliere.

- Sam Giancana, Chicago Outfit front boss

Buffalo Delegation

- Stefano "The Undertaker" Magaddino, Buffalo Family boss, charter Commission member.

New Orleans Delegation

- Carlos "Little Man" Marcello, New Orleans Family boss (some mob historians[who?] dispute his position at this time).

Tampa Delegation

- Santo "Louie Santos" Trafficante Jr., Tampa Family caporegime, moved to Havana in 1946 to oversee La Cosa Nostra and Tampa Family casino and business interests, future Tampa Family boss.

Jewish Syndicate Delegation

- Abner "Longy" Zwillman, New Jersey Jewish Syndicate boss, National Syndicate Commission member.

- Morris "Moe" Dalitz, Cleveland Jewish Syndicate boss, casino front man (Desert Inn, Las Vegas)

- Joseph "Doc" Stacher, New Jersey Jewish Syndicate boss, casino front man (Sands Hotel, Las Vegas)

- Philip "Dandy Phil" Kastel, Jewish Syndicate boss, Frank Costello's Louisiana slots operations and Tropicana Casino, Las Vegas partner.

Entertainment

- ^ "reparto:" ((subdivisions) denotes a neighborhood, the word has a connotation of modern development and is based on the allocation of land.

- ^ its early stages were supervised by Montoulieu, an (p.141)

- ^ Only fragmentary evidence remains to document views held at the time by the various participants, and those views are in any case now recast by the history of the 1959 Cuban Revolution. Nicolás Arroyo was, as minister of public works, actually a member of Batista’s government; the others, however, were not so closely aligned. Maria Romañach, Mario Romañach’s daughter, recalls her father’s distaste for Batista and suggests that the political sphere was, in Havana at least, distinctly separate from the professional activities and artistic endeavors that preoccupied him. Nicolás Quintana makes the same claim, which is corroborated to some degree by the fact that both were allowed to practice in Cuba for at least a year following the revolution, a permission that would not have been granted to anyone perceived as a close supporter of Batista. In a letter to Gabriela Menéndez written following the public presentation of the project to Batista, Wiener noted Romañach’s unexpected absence from the presentation, and added, “This attitude reflects the general tenor of Mario in connection with this project. I am afraid he is ‘lukewarm’ and … is not taking any of the risks involved and has spent very little time so far in the designing.” Wiener goes on to attribute this lack of full commitment to “attitude and temperament” and though there is no evidence that Romañach’s distancing was motivated by political or ethical reservations, it is possibly part of the explanation (letter, Paul Lester Wiener to Gabriela Menéndez, July 23, 1953 [box 13, folder 13, PLW]). Richard Bender, who worked with Wiener after the dissolution of Town Planning Associates, recalls that he delayed joining Wiener earlier because of his own distaste for the implications of the palace project, which Wiener likely understood (interviews: Maria Romañach, June 30, 2005, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Nicolás Quintana, June 9, 2005, Miami, Florida; telephone conversation: Richard Bender, September 1, 2005).[13]

- ^ 264 feet is average length of a north-south block in Manhattan; 3 block lengths in Central Havana are approximately one NYC block; therefore, the width of the proposed artificial island is closer to 300 feet.

- ^ Strong formal similarities exist between the designs of the presidential palace and the U.S. embassy in Athens. The embassy project was first published in Casabella in 1958, but given their friendship and the proximity of their offices, Sert and Gropius might well have discussed the project before then. In elevational view, the presidential palace also resembled Le Corbusier’s design for the High Court at Chandigarh, begun in 1951. The High Court facade, asymmetrically disposed and enclosed in a “box” formed by sheer side walls joined flush to a flat roof of equal thickness, was not neoclassical; its vaulting and piers, though, created a elevational profile on which Sert unmistakably drew in the design of the palace. Another precedent of which Sert and Romañach would have been aware was Le Corbusier’s 1936 proposal for a University City in Rio de Janeiro, which included a ceremonial Plaza of Ten Thousand Palms, a dense grove of royal palm trees planted in a grid at the center of the campus. A subsequent version was proposed by the Brazilian architect Lúcio Costa, who had worked with Le Corbusier on the plan and who incorporated the plaza element into an initial sketch for Brasília as the Forum de Palmieras Imperiaes. That sketch was published in the summer of 1957.[13]

- ^ The Palacio de Aldama was one of the grand colonial residences in Havana, and Sert’s notes indicate that he visited it and recognized its patio as a precedent. The Palacio de Aldama was owned by the family of Emilio del Junco’s wife, and del Junco was one of the circle of architects professionally and personally acquainted with Sert and Romañach.[13]

References

- ^ Hyde, Timothy. Constitutional Modernism: Architecture and Civil Society in Cuba, 1933-1959. Minneapolis, Minn: University of Minnesota Press, 2013. Print.

- ^ Cantón Navarro, José. History of Cuba, p. 81.

- ^ Moruzzi, Peter (2018). HAVANA BEFORE CASTRO : when Cuba was a tropical playground. Gibbs Smith. ISBN 1423603672.

- ^ Sergio., Diaz-Briquets (2006). Corruption in Cuba : Castro and beyond. Pérez-López, Jorge F. (1st ed.). Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292714823. OCLC 64098477.

- ^ Political corruption : concepts & contexts. Heidenheimer, Arnold J., Johnston, Michael, 1949- (3rd ed.). New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers. 2002. ISBN 978-0765807618. OCLC 47738358.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ R., Benjamin, Jules (1990). The United States and the origins of the Cuban Revolution : an empire of liberty in an age of national liberation. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691025360. OCLC 19811341.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Eduardo., Sáenz Rovner (2008). The Cuban connection : drug trafficking, smuggling, and gambling in Cuba from the 1920s to the Revolution. Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0807831755. OCLC 401386259.

- ^ 1943-, Pérez, Louis A. (2003). Cuba and the United States : ties of singular intimacy (Third ed.). Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 9780820324838. OCLC 707926335.

{{cite book}}:|last=has numeric name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ e.V., Transparency International. "Transparency International - Cuba". www.transparency.org. Retrieved 2018-03-18.

- ^ a b c d "HAVANA CONFERENCE: DECEMBER 20, 1946". Mob Museum. Retrieved October 8, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Wikipedia contributors, "Havana," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Havana&oldid=934957007 (accessed January 16, 2020).

- ^ a b "plan piloto de la habana 1956". Retrieved 2019-01-06.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Constitutional Modernism: Architecture and Civil Society in Cuba, 1933-1959". Retrieved 2020-01-10.

- ^ McEwen, Abigail. Revolutionary Horizons.; Yale University Press, 2016. p.106

- ^ a b c d "Josep Lluís Sert and the Havana Plan". Retrieved 2019-01-06.

- ^ See memo, José Luis Sert to Paul Lester Wiener, November 18, 1955 (box 13, folder 10, PLW). Little or no formal coordination appears to have occurred between the JNP and the municipal government of Havana, which independently carried out planning projects and public works during this time period.

- ^ See memo, José Luis Sert to Paul Lester Wiener, November 18, 1955 (box 13, folder 10, PLW). Little or no formal coordination appears to have occurred between the JNP and the municipal government of Havana, which independently carried out planning projects and public works during this time period.

- ^ Wiener, P., Michaelides, C., & Seelye, Stevenson, Value & Knecht. (1959). Plan piloto de la Habana: Directivas generales, diseños preliminares, soluciones tipo. New York: Wittenborn Art Books.

- ^ a b c "Los proyectos inconclusos o fracasados de Fidel Castro". Retrieved 2020-01-18.

- ^ Undated newspaper clipping (folder F004, JLS).

- ^ Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.