George Tyrrell: Difference between revisions

Mannanan51 (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

Mannanan51 (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 63: | Line 63: | ||

In the spring of 1879, at Dolling's invitation, Tyrrell went to London to work at a sort of [[Saint Martin's League|mission]] Dolling was starting. On Palm Sunday, he wandered into [[St Etheldreda's Church]] on Ely place. "Here was the old business, being carried on by the old firm, in the old ways; here was continuity, that took one back to the catecombs."<ref name=autob/> He converted and was [[Religious conversion#Reception of baptized persons into full communion with the Roman Catholic Church|received into the Catholic Church]] in 1879. He immediately applied to join the [[Society of Jesus]], but was advised by the provincial superior to wait a year. He spent the interim teaching at Jesuit schools in [[Cyprus]] and [[Malta]].<ref name=Rafferty>[http://www.thinkingfaith.org/articles/20090706_1.htm Rafferty, Oliver, S.J. "George Tyrrell and Catholic Modernism", ''Thinking Faith'' 6 July 2009]</ref> He joined the Jesuits in 1880 and was sent to the novitiate at [[Parkstead House|Manresa House]]. |

In the spring of 1879, at Dolling's invitation, Tyrrell went to London to work at a sort of [[Saint Martin's League|mission]] Dolling was starting. On Palm Sunday, he wandered into [[St Etheldreda's Church]] on Ely place. "Here was the old business, being carried on by the old firm, in the old ways; here was continuity, that took one back to the catecombs."<ref name=autob/> He converted and was [[Religious conversion#Reception of baptized persons into full communion with the Roman Catholic Church|received into the Catholic Church]] in 1879. He immediately applied to join the [[Society of Jesus]], but was advised by the provincial superior to wait a year. He spent the interim teaching at Jesuit schools in [[Cyprus]] and [[Malta]].<ref name=Rafferty>[http://www.thinkingfaith.org/articles/20090706_1.htm Rafferty, Oliver, S.J. "George Tyrrell and Catholic Modernism", ''Thinking Faith'' 6 July 2009]</ref> He joined the Jesuits in 1880 and was sent to the novitiate at [[Parkstead House|Manresa House]]. |

||

As early as 1882, his novice master proposed that Tyrrell withdraw from the Jesuits due to a "mental indocility" and a dissatisfaction with a number of Jesuit customs, approaches, and practices; but he was allowed to remain. Tyrrell later stated that he believed he was more inclined to Benedictine spirituality. After taking his first vows he was sent to [[Stonyhurst]] to study philosophy. In 1879, [[Pope Leo XIII]] had issued to encyclical [[Aeterni Patris]], encouraging the study of St. Thomas Aquinas. Tyrrell believed that the Jesuits endorsed Aquinas, but as interpreted by Jesuit theologian [[Francisco Suárez]]. While Tyrrell admired Aquinas, he rejected [[Scholasticism]] as inadequate. |

As early as 1882, his novice master proposed that Tyrrell withdraw from the Jesuits due to a "mental indocility" and a dissatisfaction with a number of Jesuit customs, approaches, and practices; but he was allowed to remain. Tyrrell later stated that he believed he was more inclined to Benedictine spirituality. After taking his first vows he was sent to [[Stonyhurst]] to study philosophy. In 1879, [[Pope Leo XIII]] had issued to encyclical [[Aeterni Patris]], encouraging the study of St. Thomas Aquinas. Tyrrell believed that the Jesuits endorsed Aquinas, but as interpreted by Jesuit theologian [[Francisco Suárez]]. While Tyrrell admired Aquinas, he rejected [[Scholasticism]] as inadequate. Having completed his studies at Stonyhurst, he next returned to the Jesuit school on Malta, where he spent three years teaching. He then went to [[St Beuno's Jesuit Spirituality Centre|St Beuno's College]] in Wales, to take up his theological studies. |

||

He was [[Holy Orders (Catholic Church)|ordained]] to the [[Priesthood (Catholic Church)|priesthood]] in 1891. After a brief period of pastoral work in Lancashire, he returned to Roehampton for his [[Tertianship]]. In 1893, he spent some time briefly at the Jesuit mission house in Oxford, before taking up pastoral work at [[St Helens, Merseyside]], where he was reportedly happiest during his time as a Jesuit. A little over a year later, he was sent to teach philosophy at Stonyhurst, where he came into conflict with some of the faculty for not adhering to the traditional Jesuit approach to [[Thomas Aquinas]], which was heavily influenced by the work of [[Francisco Suárez]].<ref name=Rafferty/> |

|||

| ⚫ | Extreme Ultramontanism, Tyrrell found exasperating. Between 1891 and 1906, Tyrrell published more than twenty articles in Catholic periodicals, many in the United States.<ref>[https://www.jstor.org/stable/25154819?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents Portier, William L. “George Tyrrell in America.” ''U.S. Catholic Historian'', vol. 20, no. 3, 2002, pp. 69–95. JSTOR]</ref> |

||

In 1896 he was transferred to the Jesuit House on Farm Street in London.<ref name=Hurley>[http://www.thinkingfaith.org/articles/20090714_1.htm Hurley, Michael, S.J. "George Tyrrell and John Sullivan: Sinner and Saint?", ''Thinking Faith'', 14 July 2009]</ref> It was while at Farm Street that Tyrrell discovered the work of [[Maurice Blondel]]. He was also influenced by the theology of [[John Henry Newman|Newman]], and [[Alfred Loisy]]‘s biblical scholarship. |

In 1896 he was transferred to the Jesuit House on Farm Street in London.<ref name=Hurley>[http://www.thinkingfaith.org/articles/20090714_1.htm Hurley, Michael, S.J. "George Tyrrell and John Sullivan: Sinner and Saint?", ''Thinking Faith'', 14 July 2009]</ref> It was while at Farm Street that Tyrrell discovered the work of [[Maurice Blondel]]. He was also influenced by the theology of [[John Henry Newman|Newman]], and [[Alfred Loisy]]‘s biblical scholarship. |

||

| ⚫ | Extreme Ultramontanism, Tyrrell found exasperating. Between 1891 and 1906, Tyrrell published more than twenty articles in Catholic periodicals, many in the United States.<ref>[https://www.jstor.org/stable/25154819?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents Portier, William L. “George Tyrrell in America.” ''U.S. Catholic Historian'', vol. 20, no. 3, 2002, pp. 69–95. JSTOR]</ref> |

||

In 1899 he published ''A Perverted Devotion'' in which he argued that the rationalist approach of the [[Scholasticism|Scholastics]] was not applicable to matters of [[Faith in Christianity|faith]]. Tyrrell found himself assigned to a small mission in [[Yorkshire]]. |

In 1899 he published ''A Perverted Devotion'' in which he argued that the rationalist approach of the [[Scholasticism|Scholastics]] was not applicable to matters of [[Faith in Christianity|faith]]. Tyrrell found himself assigned to a small mission in [[Yorkshire]]. |

||

Revision as of 00:07, 4 June 2019

George Tyrrell | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | George Tyrrell 6 February 1861 |

| Died | 15 July 1909 (aged 48) |

| Occupation(s) | Priest, theologian, scholar |

| Works | (See list below) |

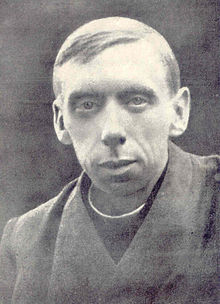

George Tyrrell SJ (6 February 1861 – 15 July 1909) was an Irish Jesuit priest (until his expulsion from the Society) and a modernist theologian and scholar. His attempts to evolve and adapt Catholic theology in the context of modern ideas made him a key figure in the modernist controversy within the Roman Catholic Church in the late 19th century.

Early life

Tyrrell was born on 6 February 1861 in Dublin, Ireland. His father, a journalist, died shortly before Tyrrell was born. George was first cousin to Irish classical scholar Robert Yelverton Tyrrell. A childhood accident resulted in him eventually becoming deaf in the right ear.[1] Limited finances caused the family to move several times.

Tyrrell was brought up as an Anglican, and around 1869 attended Rathmines School near Dublin. He was educated from 1873 at the Church of Ireland Midleton College, although his mother had difficulty affording the fees, and he left early. In 1876, he studied at Trinity College, and around 1877 met Robert Dolling who had a strong influence on him. In August 1878, Tyrrell took a post at Wexford High School, but returned to Trinity in October, on the advice of Dolling, to train for the Anglican ministry.[1]

Jesuit

In the spring of 1879, at Dolling's invitation, Tyrrell went to London to work at a sort of mission Dolling was starting. On Palm Sunday, he wandered into St Etheldreda's Church on Ely place. "Here was the old business, being carried on by the old firm, in the old ways; here was continuity, that took one back to the catecombs."[1] He converted and was received into the Catholic Church in 1879. He immediately applied to join the Society of Jesus, but was advised by the provincial superior to wait a year. He spent the interim teaching at Jesuit schools in Cyprus and Malta.[2] He joined the Jesuits in 1880 and was sent to the novitiate at Manresa House.

As early as 1882, his novice master proposed that Tyrrell withdraw from the Jesuits due to a "mental indocility" and a dissatisfaction with a number of Jesuit customs, approaches, and practices; but he was allowed to remain. Tyrrell later stated that he believed he was more inclined to Benedictine spirituality. After taking his first vows he was sent to Stonyhurst to study philosophy. In 1879, Pope Leo XIII had issued to encyclical Aeterni Patris, encouraging the study of St. Thomas Aquinas. Tyrrell believed that the Jesuits endorsed Aquinas, but as interpreted by Jesuit theologian Francisco Suárez. While Tyrrell admired Aquinas, he rejected Scholasticism as inadequate. Having completed his studies at Stonyhurst, he next returned to the Jesuit school on Malta, where he spent three years teaching. He then went to St Beuno's College in Wales, to take up his theological studies.

He was ordained to the priesthood in 1891. After a brief period of pastoral work in Lancashire, he returned to Roehampton for his Tertianship. In 1893, he spent some time briefly at the Jesuit mission house in Oxford, before taking up pastoral work at St Helens, Merseyside, where he was reportedly happiest during his time as a Jesuit. A little over a year later, he was sent to teach philosophy at Stonyhurst, where he came into conflict with some of the faculty for not adhering to the traditional Jesuit approach to Thomas Aquinas, which was heavily influenced by the work of Francisco Suárez.[2]

In 1896 he was transferred to the Jesuit House on Farm Street in London.[3] It was while at Farm Street that Tyrrell discovered the work of Maurice Blondel. He was also influenced by the theology of Newman, and Alfred Loisy‘s biblical scholarship.

Extreme Ultramontanism, Tyrrell found exasperating. Between 1891 and 1906, Tyrrell published more than twenty articles in Catholic periodicals, many in the United States.[4]

In 1899 he published A Perverted Devotion in which he argued that the rationalist approach of the Scholastics was not applicable to matters of faith. Tyrrell found himself assigned to a small mission in Yorkshire.

Asked to repudiate his theories in 1906, Tyrrell declined and was dismissed from the Society of Jesus by superior general Franz X. Wernz.

Pope Pius X's 1907 encyclical Pascendi dominici gregis condemned modernism. Tyrrell contributed two letters to The Times critical of the encyclical[3] and was subsequently excommunicated.

Tyrrell argued that most biblical scholarship and devotional reflection, such as the quest for the historic Jesus, involves elements of self-conscious self-reflection. His famous image, criticising Adolf von Harnack's Liberal Protestant view of Scripture, is of peering into a well, in which we see our own face reflected in the dark water deep below:

- "The Christ that Harnack sees, looking back through nineteen centuries of "Catholic darkness", is only the reflection of a Liberal Protestant face, seen at the bottom of a deep well."[5]

He argued that the pope should not act as an autocrat but a "spokesman for the mind of the Holy Spirit in the Church".[6]

Tyrrell was disciplined under Pope Pius X for advocating "the right of each age to adjust the historico-philosophical expression of Christianity to contemporary certainties, and thus to put an end to this utterly needless conflict between faith and science which is a mere theological bogey."[citation needed]

He was suspended from the sacraments the following year and finally excommunicated in 1908. He died the following year, still considering himself to be a devout Catholic. Tyrrell was the only Jesuit to be expelled by a Jesuit general in the twentieth century until the Spanish father general, Pedro Arrupe, expelled Huub Oosterhuis in 1969. Modernism played a major role in both cases.

With the condemnation of modernism, first in the 65 propositions of the decree Lamentabili sane exitu in July 1907 and then in the encyclical Pascendi dominici gregis in September 1907, Tyrrell's fate was sealed. He was deprived of the sacraments – described by Peter Amigo, Bishop of Southwark, as "a minor excommunication" – for his robust criticisms of Pascendi which appeared in The Times on 30 September and 1 October 1907.[7] In his rebuttal of Pius X's encyclical, Tyrrell alleged that the Church's thinking was based on a theory of science and on a psychology that seemed as strange as astrology to the modern mind. Tyrrell accused Pascendi of equating Catholic doctrine with Scholastic theology and of having a completely naïve view of the idea of doctrinal development. He furthermore asserted that the encyclical tried to show the "modernist" that he was not a Catholic, but all it succeeded in doing was showing that he was not a Scholastic.[2]

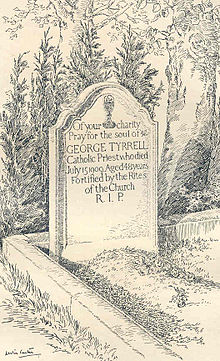

Death

His last two years were spent mainly in Storrington. He was given extreme unction on his deathbed in 1909, but as he refused to abjure his modernist views was denied burial in a Catholic cemetery.[8] A priest, his friend Henri Brémond, who was present at the burial made a sign of the cross over Tyrrell's grave, for which Bremond was temporarily suspended a divinis by Bishop Amigo for some time.[9]

A near contemporary account places most of the blame for the disagreement between the modern Catholic philosophers and the Vatican on the then Papal Secretary of State, Cardinal Merry de Val's "irreconciliable and reactionary attitude".[10]

According to Michael Hurley SJ, Tyrrell's views were in large part vindicated by the Second Vatican Council.[3]

Selected writings

- Nova et Vetera: Informal Meditations, 1897

- Hard Sayings: A Selection of Meditations and Studies, Longmans, Green & Co., 1898

- External Religion: Its Use and Abuse, B. Herder, 1899

- The Faith of the Millions 1901

- Lex Orandi: or, Prayer & Creed, Longmans, Green & Co., 1903

- Lex Credendi: A Sequel to Lex Orandi, Longmans, Green & Co., 1906

- Through Scylla and Charybdis: or, The Old Theology and the New, Longmans, Green & Co., 1907

- A Much-Abused Letter, Longmans, Green, and Co., 1907

- Medievalism: A Reply to Cardinal Mercier, Longmans, Green, and Co. 1908

- The Church and the Future, The Priory Press, 1910

- Christianity at the Cross-Roads, Longmans, Green and Co., 1910

- Autobiography and Life of George Tyrrell, Edward Arnold, 1912

- Essays on Faith and Immortality, Edward Arnold, 1914

Articles

- "The Clergy and the Social Problem," The American Catholic Quarterly Review, Vol. XXII, 1897.

- "The Old Faith and the New Woman", The American Catholic Quarterly Review, Vol. XXII, 1897.

- "The Church and Scholasticism", The American Catholic Quarterly Review, Vol. XXIII, 1898.

References

- ^ a b c Tyrrell, George. Autobiography of George Tyrrell, 1861-1884, Longmans, Green & Company, 1912, p. 33

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c Rafferty, Oliver, S.J. "George Tyrrell and Catholic Modernism", Thinking Faith 6 July 2009

- ^ a b c Hurley, Michael, S.J. "George Tyrrell and John Sullivan: Sinner and Saint?", Thinking Faith, 14 July 2009

- ^ Portier, William L. “George Tyrrell in America.” U.S. Catholic Historian, vol. 20, no. 3, 2002, pp. 69–95. JSTOR

- ^ George Tyrrell, Christianity at the Crossroads (1913 ed.), pg. 44

- ^ Saunders, F.S. (2011). The Woman Who Shot Mussolini: A Biography. Henry Holt and Company. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-4299-3508-1. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ "The Pope and Modernism", Father Tyrrell's Articles, at The West Australian (Perth, WA), 2 November 1907, p. 2. Also available at Eastern Daily Mail and Straits Morning Advertiser, 5 November 1907, page 1.

- ^ Fergus Kerr, Twentieth-Century Catholic Theologians (Blackwell, 2007, p. 5)

- ^ SOFN.org Archived 29 April 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Littlefield, Walter. "Indiscretions of Cardinal Merry De Val: Acts of the Papal Secretary of State which have laid him open to Criticism", New York Times, April 10, 1910

Further reading

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Inge, William Ralph (1919). "Roman Catholic Modernism." In: Outspoken Essays. London: Longmans, Green & Co., pp. 137–171.

-Maher, Anthony M. (2018). 'The Forgotten Jesuit of Catholic Modernism: George Tyrrell's Prophetic Theology.' Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress Press.

- May, J. Lewis (1932). Father Tyrrell and the Modernist Movement. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode.

- Moore, J.F. (1920). "The Meaning of Modernism," The University Magazine, Vol. XIX, No. 2, pp. 172–178.

- Petre, Maude (1912). Autobiography and Life of George Tyrrell. London: E. Arnold.

- Ratté, John (1967). Three Modernists: Alfred Loisy, George Tyrrell, William L. Sullivan. New York: Sheed & Ward.

- Rigg, James McMullen (1912). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography (2nd supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Root, John D. (1977). "English Catholic Modernism and Science: The Case of George Tyrrell," The Heythrop Journal, Vol. XVIII, No. 3, pp. 271–288.

- Sagovsky, Nicholas (1990). On God's Side: A Life of George Tyrrell. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Sagovsky, Nicholas. "Tyrrell, George (1861–1909)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36606. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Savage, Allan (2012). The "Avant-Garde" Theology of George Tyrrell: Its Philosophical Roots Changed My Theological Thinking. (CreateSpace.com)

- Schultenover, David G. (1981). George Tyrrell: In Search of Catholicism. Shepherdstown, West Virginia: Patmos Press.

- Wells, David F. (1972). "The Pope as Antichrist: The Substance of George Tyrrell's Polemic," Harvard Theological Review, Vol. LXV, No. 2, pp. 271–283.

- Wells, David F. (1979). The Prophetic Theology of George Tyrrell. Chico, CA: Scholars Press.

- Utz, Richard (2010). "Pi(o)us Medievalism vs. Catholic Modernism: The Case Of George Tyrell." In: The Year's Work in Medievalism, Vol. XXV. Eugene, Or.: Wipf & Stock Publishers, pp. 6–11.

External links

- Brief biographical notes on George Tyrrell

- Michael Morton, "Catholic Modernism (1860–1914)"

- International Catholic University: James Hitchcock, "Introduction to Modernism": George Tyrrell, among essays headed "Note: Most of the works dealing with Modernism are sympathetic to the Modernists, and students should maintain a critical stance towards the assigned readings."

- Works by George Tyrrell at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about George Tyrrell at Internet Archive

- 1861 births

- 1909 deaths

- Catholicism-related controversies

- Converts to Roman Catholicism from Anglicanism

- Former Jesuits

- Irish Anglicans

- Irish Roman Catholic priests

- Irish Roman Catholic theologians

- People from Dublin (city)

- Irish Jesuits

- People educated at Midleton College

- People excommunicated by the Catholic Church

- Modernism in the Catholic Church