Hayao Miyazaki: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 96.245.60.174 (talk) to last version by DelayTalk |

Article rewrite. |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Use mdy dates|date=August 2016}} |

{{Use mdy dates|date=August 2016}} |

||

{{Infobox person |

{{Infobox person |

||

| name = Hayao Miyazaki |

| name = Hayao Miyazaki |

||

| image = Hayao Miyazaki.jpg |

| image = Hayao Miyazaki.jpg |

||

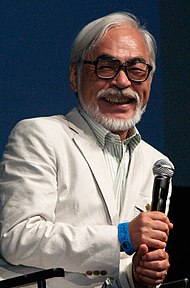

| caption = Miyazaki at the |

| caption = Miyazaki at the [[Venice Film Festival]] in 2008 |

||

| native_name = 宮崎 駿 |

| native_name = 宮崎 駿 |

||

| native_name_lang = ja |

| native_name_lang = ja |

||

| birth_name = |

| birth_name = |

||

| birth_date = {{birth date and age|1941|1|5|mf= yes}} |

| birth_date = {{birth date and age|1941|1|5|mf= yes}} |

||

| birth_place = [[Bunkyō]], [[Tokyo]], Japan |

| birth_place = [[Bunkyō]], [[Tokyo]], Japan |

||

| nationality = Japanese |

| nationality = [[Japan|Japanese]] |

||

| occupation ={{flatlist| |

| occupation = {{flatlist| |

||

*[[Film director]] |

*[[Film director]] |

||

*[[Film producer|producer]] |

*[[Film producer|producer]] |

||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

*[[author]] |

*[[author]] |

||

*[[manga artist]]}} |

*[[manga artist]]}} |

||

| years_active |

| years_active = 1964–present |

||

| employer = {{Unbulleted list|[[Toei Animation]] (1963–71)|[[Shin-Ei Animation|A-Pro]] (1971–73)|Zuiyō Eizō (1973–75)|[[Nippon Animation]] (1975–79)|[[TMS Entertainment|Telecom Animation Film]] (1979–82)|[[Studio Ghibli]] (1985–present)}} |

|||

| spouse = {{marriage|Akemi Ōta| 1965}} |

|||

| alma_mater = [[Gakushuin University]] |

|||

| children = 2 [[Gorō Miyazaki]], [[Keisuke Miyazaki]] |

|||

| spouse = {{marriage|Akemi Ōta| 1965}} |

|||

| children = {{Unbulleted list|[[Gorō Miyazaki]]|Keisuke Miyazaki}} |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

{{Anime and manga}} |

{{Anime and manga}} |

||

{{Nihongo|'''Hayao Miyazaki'''|宮崎 駿|Miyazaki Hayao|born January 5, 1941 |

{{Nihongo|'''Hayao Miyazaki'''|宮崎 駿|Miyazaki Hayao|born January 5, 1941|lead=yes}} is a Japanese film director, producer, screenwriter, animator, author, and [[manga artist]]. A co-founder of [[Studio Ghibli]], a film and animation studio, he has attained international acclaim as a masterful storyteller and as a maker of [[anime]] feature films, and is widely regarded as one of the greatest animation directors. |

||

Born in [[Bunkyō, Tokyo |

Born in [[Bunkyō]], Tokyo, Miyazaki expressed interest in manga and animation from an early age, and he joined [[Toei Animation]] in 1963. During his early years at Toei Animation he worked as an [[Inbetweening|in-between artist]] and later collaborated with director [[Isao Takahata]]. Notable films to which Miyazaki contributed at Toei include ''[[Doggie March]]'' and ''[[Gulliver's Travels Beyond the Moon]]''. He provided key animation to other films at Toei, such as ''[[Puss in Boots (1969 film)|Puss in Boots]]'' and ''[[Animal Treasure Island]]'', before moving to [[Shin-Ei Animation|A-Pro]] in 1971, where he co-directed ''[[Lupin the Third Part I]]'' alongside Takahata. After moving to Zuiyō Eizō (later known as [[Nippon Animation]]) in 1973, Miyazaki worked as an animator on ''[[World Masterpiece Theater]]'', and directed the television series ''[[Future Boy Conan]]''. He joined [[TMS Entertainment|Telecom Animation Film]] in 1979 to direct his first feature films, ''[[The Castle of Cagliostro]]'' in 1979 and ''[[Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (film)|Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind]]'' in 1984, as well as the television series ''[[Sherlock Hound]]''. |

||

Miyazaki co-founded Studio Ghibli in 1985. He directed several films with Ghibli, including ''[[Castle in the Sky]]'' in 1986, ''[[My Neighbor Totoro]]'' in 1988, ''[[Kiki's Delivery Service]]'' in 1989, and ''[[Porco Rosso]]'' in 1992. The films were met with commercial and critical success in Japan. Miyazaki's film ''[[Princess Mononoke]]'' was the first animated film to win the [[Japan Academy Prize for Picture of the Year]], and briefly became the [[List of highest-grossing films in Japan|highest-grossing film in Japan]] following its release in 1997;{{efn|name="Titanic"|''Princess Mononoke'' was eclipsed as the [[List of highest-grossing films in Japan|highest-grossing film in Japan]] by ''[[Titanic (1997 film)|Titanic]]'', released several months later.{{sfn|Ebert|1999}}}} its distribution to the [[Western world]] greatly increased Ghibli's popularity and influence outside Japan. His 2001 film ''[[Spirited Away]]'' became the highest-grossing film in Japanese history, winning the [[Academy Award for Best Animated Feature]] at the [[75th Academy Awards]] and considered among the [[List of films considered the best|greatest animation films of all time]]. Miyazaki's later films—''[[Howl's Moving Castle (film)|Howl's Moving Castle]]'', ''[[Ponyo]]'', and ''[[The Wind Rises]]''—also enjoyed commercial and critical success. Following the release of ''The Wind Rises'', Miyazaki announced his retirement from feature films. He returned to work on a new feature film in 2016. |

|||

He continued to work in various roles in the animation industry with various studios until he directed his first feature film, ''[[The Castle of Cagliostro]]'', a ''Lupin the Third'' story, released in 1979. After the success of his next film, ''[[Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (film)|Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind]]'' (1984), he co-founded Studio Ghibli, where he continued to produce many feature films. |

|||

Miyazaki's works are characterized by the recurrence of progressive themes, such as humanity's relationship with [[nature]] and technology, and the difficulty of maintaining a [[pacifist]] ethic. His films' protagonists are often strong girls or young women, and several of his films present morally ambiguous antagonists with redeeming qualities. Miyazaki's works have been highly praised and [[List of accolades received by Hayao Miyazaki|awarded]]; in November 2014, Miyazaki was awarded the [[Academy Honorary Award]], for his impact on animation and cinema. In 2002, American [[film critic]] [[Roger Ebert]] suggested that Miyazaki may be the best animation filmmaker in history, praising the depth and artistry of his films.{{sfn|Ebert|2002}} |

|||

While Miyazaki's films have long enjoyed both commercial and critical success in Japan, he remained largely unknown to the West until [[Miramax Films]] released ''[[Princess Mononoke]]'' in 1997. ''Princess Mononoke'' was briefly the highest-grossing film in Japan until it was eclipsed by another 1997 film, ''[[Titanic (1997 film)|Titanic]]'', and it became the first animated film to win Picture of the Year at the [[Japan Academy Prize (film award)|Japanese Academy Awards]]. Miyazaki's next film, ''[[Spirited Away]]'' (2001), won Picture of the Year at the Japanese Academy Awards, and was the first anime film to win an [[Academy Award|American Academy Award]]. |

|||

== Early life == |

|||

Miyazaki's films often contain recurrent themes, like humanity's relationship with [[nature]] and technology, and the difficulty of maintaining a [[pacifist]] ethic. His films' protagonists are often strong girls or young women.<ref name="Napier" /> While two of his films, ''[[The Castle of Cagliostro]]'' and ''[[Castle in the Sky]]'', involve traditional [[villain]]s, his other films like ''[[Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (film)|Nausicaä]]'' and ''Princess Mononoke'' present morally ambiguous antagonists with redeeming qualities. He co-wrote films ''[[Arrietty|The Secret World of Arrietty]]'', released in July 2010 in Japan and February 2012 in the United States; and ''[[From Up on Poppy Hill]]'' released in July 2011 in Japan and March 2013 in the United States. |

|||

Hayao Miyazaki was born on January 5, 1941, in the town of Akebono-cho in [[Bunkyō]], Tokyo, the second of four sons.{{sfn|Nausicaa.net|1994}} His father, [[Katsuji Miyazaki]], was the director of [[Miyazaki Airplane]], which manufactured rudders for fighter planes during [[World War II]].{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=26}} The business allowed his family to remain affluent during Miyazaki's early life.{{sfn|Miyazaki|1988}} During the war, when Miyazaki was three years old, his family evacuated to [[Utsunomiya]].{{efn|{{harvtxt|McCarthy|1999}} states Miyazaki was evacuated at age three and began school as an evacuee in 1947.{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=26}} {{harvtxt|Nausicaa.net|1994}} references the evacuation as "[b]etween 1944 and 1946".{{sfn|Nausicaa.net|1994}}}} After the [[Bombing of Utsunomiya during World War II|bombing of Utsunomiya]] in July 1945, Miyazaki's family evacuated to [[Kanuma]].{{sfn|Nausicaa.net|1994}}{{sfn|Miyazaki|1988}} The bombing left a lasting impression on Miyazaki, who was aged four at the time.{{sfn|Miyazaki|1988}} From 1947 to 1955, Miyazaki's mother suffered from [[spinal tuberculosis]]; she spent the first few years in hospital, before being nursed from home.{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=26}} |

|||

Miyazaki began school in 1947, at an [[elementary school]] in Utsunomiya, completing the first through third grades. After his family moved back to [[Suginami-ku]], Miyazaki completed the fourth grade at Ōmiya Elementary School, and fifth grade at Eifuku Elementary School. After graduating from Eifuku, he attended Ōmiya Junior High.{{sfn|Nausicaa.net|1994}} He aspired to become a manga artist,{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=27}} but discovered he could not draw people;{{sfn|Nausicaa.net|1994}} instead, he only drew planes, tanks, and battleships for several years.{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=27}} Miyazaki was influenced by several manga artists, such as [[de:Fukushima Tesuji|Tetsuji Fukushima]], Soji Yamakawa and [[Osamu Tezuka]]. Miyazaki destroyed much of his early work, believing it was "bad form" to copy Tezuka's style as it was hindering his own development as an artist.{{sfn|Miyazaki|1996|p=193}}{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=28}}{{sfn|Comic Box|1982|p=80}} After graduating from Ōmiya Junior High and Ōmiya Middle School, Miyazaki attended Toyotama High School.{{sfn|Nausicaa.net|1994}}{{sfn|Miyazaki|1996|p=436}} During his third year, Miyazaki's interest in animation was sparked by ''[[Panda and the Magic Serpent]]'' (1958).{{sfn|Nausicaa.net|1994}} He "fell in love" with the movie's heroine and it left a strong impression on him.{{efn|{{harvtxt|McCarthy|1999}} states: "He realized the folly of trying to succeed as manga writer by echoing what was fashionable, and decided to follow his true feelings in his work even if that might seem foolish."{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=29}}}} After graduating from Toyotama, Miyazaki attended [[Gakushuin University]] and was a member of the "Children's Literature Research Club", the "closest thing to a [[comics]] club in those days".{{sfn|Nausicaa.net|1994}} He graduated from Gakushuin in 1963 with degrees in [[political science]] and [[economics]].{{sfn|Nausicaa.net|1994}} |

|||

Miyazaki's newest film ''[[The Wind Rises]]'' was released on July 20, 2013 and screened internationally in February 2014.<ref>{{cite web|title=Disney to Release The Wind Rises in N. America|url= http://www.animenewsnetwork.com/news/2013-08-27/disney-to-release-the-wind-rises-in-n-america |publisher=Anime News Network | accessdate = September 1, 2013}}</ref> The film would go on to earn him his third American Academy Award nomination and first [[Golden Globe Award]] nomination. Miyazaki announced on September 1, 2013 that ''The Wind Rises'' would be his final feature-length movie.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.usnews.com/news/world/articles/2013/09/01/japans-miyazaki-to-retire-after-11-feature-films |title= Japan's Miyazaki to retire after 11 feature films}}</ref><ref name="Anime News Network">{{cite web|title=Hayao Miyazaki Retires From Making Feature Films|url= http://www.animenewsnetwork.com/news/2013-09-01/hayao-miyazaki-to-retire-from-making-feature-films | publisher = Anime News Network|accessdate=September 1, 2013}}</ref> In November 2014, Miyazaki was awarded an [[Honorary Academy Award]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2014/11/10/national/miyazaki-is-second-japanese-to-receive-honorary-oscar/#.VOkcAMXgHa8|title=Miyazaki is second Japanese to receive honorary Oscar|date=November 10, 2014|work=The Japan Times|accessdate=February 28, 2015}}</ref> for his impact on animation and cinema. He is the second Japanese filmmaker to win this award, after [[Akira Kurosawa]] in 1990.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2014/11/10/national/miyazaki-is-second-japanese-to-receive-honorary-oscar/#.VcGI9YtrGyd |title=Miyazaki is second Japanese to receive honorary Oscar |publisher=The Japan Times |date=2014-11-10 |accessdate=2017-03-30}}</ref> In 2002, American [[film critic]] [[Roger Ebert]] suggested that Miyazaki may be the best animation filmmaker in history, praising the depth and artistry of his films.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.rogerebert.com/interviews/hayao-miyazaki-interview|title=Hayao Miyazaki interview|first=Roger |last=Ebert|authorlink=Roger Ebert|work=RogerEbert.com|date=September 12, 2002|accessdate=April 30, 2015}}</ref> |

|||

== |

== Career == |

||

Miyazaki was born in the town of Akebono-cho in [[Bunkyō, Tokyo|Bunkyō]], Tokyo, the second of four sons born to [[Katsuji Miyazaki]].<ref name="HC"/><ref name=bio>{{cite web | url=http://www.nausicaa.net/miyazaki/miyazaki/miyazaki_biography.txt | title=Hayao Miyazaki Biography Revision 2 (6/24/94) | publisher=Nausicaa.net | date=June 24, 1994 | accessdate=August 16, 2013}}</ref> His father was director of [[Miyazaki Airplane]], which made rudders for [[A6M Zero]] fighter planes during [[World War II]].{{sfn|McCarthy|1999| page=26}} During the war, when Miyazaki was only three years old, the family evacuated to [[Utsunomiya]] and later to [[Kanuma]] in [[Tochigi Prefecture]] where the Miyazaki Airplane factory was located.{{efn|McCarthy notes Miyzaki's getting evacuated at age three and starting school as an evacuee in 1947.{{sfn|McCarthy| 1999 | page= 26 }} The Nausicaa.net biography states, "Between 1944 and 1946".<ref name=bio /> In order to preserve accuracy of the ambiguous timeline, no synthesis will be made to state when this occurred.}} Miyazaki has said of his early life that his family was affluent, and could live comfortably during the war because of his father and uncle's profitable work in the war industry, but he has also noted that as a 4-and-a-half year old, experiencing the night time firebombing raids on Utsunomiya in July 1945 left a lasting impression on him. During his May 22, 1988 lecture at the film festival in Nagoya he retold the account of his family's hasty retreat from the burning town, without providing a ride to other people in need of transportation, and he recalled how the fires had coloured the night sky as he looked back towards the city after they had fled to a safer distance.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Miyazaki |first=Hayao |date= May 22, 1988 | publication-date=July 16, 1995|number=1166|editor-last=Takeuchi | editor-first=Masatoshi| script-title=ja:宮崎駿講演採録 |trans_title= Hayao Miyazaki Lecture record |pages=57–58 |url=http://www.kinejun.com |language=Japanese |journal=Kinema Junpo|location=Tokyo |publisher=Kinema Junpo |accessdate=February 3, 2014}}</ref> |

|||

In 1947, Miyazaki began school at Utsunomiya City elementary, completing the first through third grades before his family moved back to [[Suginami-ku]], where he completed the fourth grade at Omiya Elementary School. For fifth grade, he went to the new Eifuku Elementary School.<ref name=bio /> Miyazaki graduated from Eifuku and attended Omiya Junior High. During this time, Miyazaki's mother suffered from [[spinal tuberculosis]] and was bedridden from 1947 until 1955. She spent the first few years mostly in the hospital, but was eventually able to be nursed from home.{{sfn|McCarthy| 1999 | page= 26 }} Miyazaki aspired to become a manga author from an early age. He read the illustrated stories in boys' magazines and acknowledges the influences of creative artists of the medium, such as {{Nihongo|Tetsuji Fukushima|福島鉄次}}, Soji Yamakawa and [[Osamu Tezuka]]. It was as a result of Tezuka's influence that Miyazaki would later destroy much of his early work, believing it was "bad form" to copy Tezuka's style because it was hindering his own development as an artist.{{efn|Miyazaki(2009),{{sfn|Miyazaki|2009|pages=193–197}} McCarthy (1999){{sfn|McCarthy| 1999 | page= 28 }} Comic Box (1982), page 80.<ref name="Comic_Box_JPN(1982)">{{cite journal |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |script-title=ja:特集宮崎駿 「風の谷のナウシカ」1 | trans_title=Special Edition Hayao Miyazaki ''Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind'' 1 | url=http://www.comicbox.co.jp/comicbox/column/backnumber.html | language=Japanese | journal=Comic Box | publisher=Fusion Products | issue=3 | pages=77–137 | accessdate=November 19, 2013}}</ref> }} |

|||

After graduating from Omiya Junior High, Miyazaki attended Toyotama High School. During his third year, Miyazaki's interest in animation was sparked by ''[[Panda and the Magic Serpent|The Tale of the White Serpent]]''.<ref name=bio /> He "fell in love" with the movie's heroine and it left a strong impression on him. As Helen McCarthy put it; "He realized the folly of trying to succeed as manga writer by echoing what was fashionable, and decided to follow his true feelings in his work even if that might seem foolish."{{sfn|McCarthy| 1999 | page=29 }} His interest really began by the time he began to attend high school. He was determined to become some type of artist. His interests were mainly in anime and manga when the two were beginning to arise at the time.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.notablebiographies.com/newsmakers2/2006-Le-Ra/Miyazaki-Hayao.html |title=Hayao Miyazaki Biography - family, children, parents, story, wife, school, mother, young, son - Newsmakers Cumulation |publisher=Notablebiographies.com |date= |accessdate=2017-03-30}}</ref> To become an animator, with an independent style, Miyazaki had to learn to draw the human figure.<ref name="HC">{{cite web|url= http://www.nausicaa.net/miyazaki/miyazaki/miyazaki_biography.txt | title= Hayao Miyazaki Biography | edition = Revision 2|date=June 24, 1994|accessdate=February 19, 2007|publisher= Nausicaa.net| format = plain text |first=Steven|last=Feldman}}</ref> After graduating from Toyotama, Miyazaki attended [[Gakushuin University]] and was a member of the university's "[[Children's Literature]] Research Club", the "closest thing to a [[comics]] club in those days". Miyazaki graduated from Gakushuin in 1963 with degrees in [[political science]] and [[economics]].<ref name="HC"/> |

|||

==Animation career== |

|||

{{Main article|Works of Hayao Miyazaki}} |

{{Main article|Works of Hayao Miyazaki}} |

||

===Early career |

=== Early career === |

||

[[Image:Isao Takahata.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Miyazaki first worked with [[Isao Takahata]] in 1964, spawning a collaboration which lasted for the remainder of his career.{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=30}}]] |

|||

In April 1963, Miyazaki got a job at [[Toei Animation]], working as an [[Inbetweening|in-between artist]] on the theatrical feature anime ''[[Doggie March|Watchdog Bow Wow]]'' and the anime television series ''Wolf Boy Ken''. He was a leader in a labor dispute soon after his arrival, becoming chief secretary of Toei's labor union in 1964.{{sfn|McCarthy| 1999 | page=30 }} He first gained recognition while working as an in-between artist on the Toei production ''[[Gulliver's Travels Beyond the Moon]]'' in 1965. He found the original ending to the script unsatisfactory and pitched his own idea, which became the ending used in the finished film. |

|||

In 1963, Miyazaki was employed at [[Toei Animation]].{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=30}} He worked as an [[Inbetweening|in-between artist]] on the theatrical feature anime ''[[Doggie March]]'' and the television anime ''Wolf Boy Ken'' (both 1963). He also worked on ''[[Gulliver's Travels Beyond the Moon]]'' (1964).{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=217}} He was a leader in a labor dispute soon after his arrival, and became chief secretary of Toei's labor union in 1964.{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=30}} Miyazaki later worked as chief animator, concept artist, and scene designer on ''[[The Great Adventure of Horus, Prince of the Sun]]'' (1968). Throughout the film's production, Miyazaki worked closely with his mentor, [[Yasuo Ōtsuka]], whose approach to animation had a profound impact on Miyazaki's work.{{sfn|LaMarre|2009|pp=56ff}} Directed by [[Isao Takahata]], with whom Miyazaki would continue to collaborate for the remainder of his career, the film was highly praised, and deemed a pivotal work in the evolution of animation.{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=38}}{{sfn|Anime News Network|2001}}{{sfn|Drazen|2002|pp=254ff}} |

|||

In 1968 Miyazaki played an important role as chief animator, concept artist, and scene designer on ''[[Horus: Prince of the Sun]]'', a landmark animated film. Through the collaborative process adopted for the project he was able to contribute his ideas and work closely with his mentor, [[Animation Director]] [[Yasuo Ōtsuka]], whose innovative approach to animation had a profound impact on Miyazaki's work. The film was directed by [[Isao Takahata]], with whom he continued to collaborate for the remainder of his career. In Kimio Yabuki's ''[[Puss in Boots (1969 film)|Puss in Boots]]'' (1969), Miyazaki again provided key animation as well as designs, storyboards and story ideas for key scenes in the film, including the climactic chase scene. He also illustrated the manga, as a promotional [[Tie-in]], for this production of ''Puss in Boots''. Toei Animation produced two more sequels with the 'Puss in Boots' from this film, during the 1970s, and the character would ultimately become the studio's mascot, but Miyazaki wasn't involved with any of the sequels. Shortly thereafter, Miyazaki proposed scenes in the screenplay for ''[[Flying Phantom Ship]]'', in which military tanks would roll into downtown Tokyo and cause mass hysteria, and was hired to storyboard and animate those scenes. In 1971, Miyazaki played a decisive role in developing structure, characters and designs for [[Hiroshi Ikeda (director)|Hiroshi Ikeda]]'s adaptation of ''[[Doubutsu Takarajima|Animal Treasure Island]]'' and the adaptation of ''[[Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves (1971 film)|Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves]]'' by Hiroshi Shidara. Miyazaki also helped in the storyboarding and key animating of pivotal scenes in both films and made a promotional manga for ''Animal Treasure Island''.<!--See Manga section below--> |

|||

Under the [[Pseudonymity|pseudonym]] {{Nihongo|Saburō Akitsu|秋津三朗}}, Miyazaki wrote and illustrated the manga ''[[Sabaku no Tami|People of the Desert]]'', published in 26 instalments between September 1969 and March 1970 in {{Nihongo|''Boys and Girls Newspaper''|少年少女新聞 |Shōnen shōjo shinbun}}.{{sfn|Miyazaki|1996|p=438}} He was influenced by illustrated stories such as Fukushima's {{Nihongo|''Evil Lord of the Desert''|沙漠の魔王|Sabaku no maō}}.{{sfn|Miyazaki|1996|p=194}} Miyazaki also provided key animation for ''[[The Wonderful World of Puss 'n Boots]]'' (1969), directed by [[Kimio Yabuki]].{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=219}} He created a 12-chapter [[manga]] series as a promotional [[tie-in]] for the film; the series ran in the Sunday edition of ''[[Tokyo Shimbun]]'' from January to March 1969.{{sfn|Comic Box|1982|p=111}}{{sfn|''Animage''|1983}} Miyazaki later proposed scenes in the screenplay for ''[[Flying Phantom Ship]]'' (1961), in which military tanks would cause mass hysteria in downtown Tokyo, and was hired to storyboard and animate the scenes.{{sfn|Nausicaa.net}} In 1971, he developed structure, characters and designs for [[Hiroshi Ikeda (director)|Hiroshi Ikeda]]'s adaptation of ''[[Animal Treasure Island]]''; he created the 13-part manga adaptation, printed in ''Tokyo Shimbun'' from January to March 1971.{{sfn|Comic Box|1982|p=111}}{{sfn|''Animage''|1983}}{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=27, 219}} Miyazaki also provided key animation for ''[[Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves|Ali Baba and the Forthy Thieves]]'' (1971).{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=220}} |

|||

Miyazaki left Toei for [[Shin-Ei Animation|A Pro]] in August 1971, where he co-directed 14 episodes of the first ''[[Lupin III]]'' series with Isao Takahata. That year the two also began pre-production on a ''[[Pippi Longstocking]]'' series and drew extensive story boards for it. However, after traveling to [[Sweden]] to conduct research for the film and meet the original author, [[Astrid Lindgren]], permission was refused to complete the project, and it was canceled as a result.{{sfn|McCarthy| 1999 | page=89 }} In 1972 and 1973 Miyazaki conceived, wrote, designed and animated two ''[[Panda! Go, Panda!]]'' shorts which were directed by Takahata. |

|||

Miyazaki left Toei Animation in August 1971, and was hired at [[Shin-Ei Animation|A-Pro]],{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=39}} where he directed, or co-directed with Takahata, 23 episodes of ''[[Lupin the Third Part I]]''.{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=220}} The two also began pre-production on a series based on [[Astrid Lindgren]]'s ''[[Pippi Longstocking]]'' books, designing extensive storyboards; the series was canceled after Miyazaki and Takahata met Lindgren, and permission was refused to complete the project.{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=39}} In 1972 and 1973, Miyazaki wrote, designed and animated two ''[[Panda! Go, Panda!]]'' shorts, directed by Takahata.{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=221}} After moving to from A-Pro to Zuiyō Eizō in June 1973,{{sfn|Miyazaki|1996|p=440}} Miyazaki and Takahata worked on ''[[World Masterpiece Theater]]'', which featured their animation series ''[[Heidi, Girl of the Alps]]'', an adaptation of [[Johanna Spyri]]'s ''[[Heidi]]''. Zuiyō Eizō continued as [[Nippon Animation]] in July 1975.{{sfn|Miyazaki|1996|p=440}} Miyazaki also directed the television series ''[[Future Boy Conan]]'' (1978), an adaptation of [[Alexander Key]]'s ''[[The Incredible Tide]]''.{{sfn|Miyazaki|1996|p=441}} |

|||

After their move to [[Zuiyo Eizo]], in 1974, he worked as an animator on the [[World Masterpiece Theater]] with Takahata, which included their adaptation of the first part of [[Johanna Spyri]]'s [[Heidi]] novel into the animated television series ''[[Heidi, Girl of the Alps]]''. The company continued as Nippon Animation in 1975. Miyazaki also directed the television series ''[[Future Boy Conan]]'' (1978), an adaptation of the children's novel ''[[The Incredible Tide]]'' by [[Alexander Key]]. The main antagonist is the leader of the [[city-state]] of Industria who attempts to revive lost technology. The series also elaborates on the characters and events in the book, and is an early example of characterizations which recur throughout Miyazaki's later work: a girl who is in touch with nature, a warrior woman who appears menacing but is not an antagonist, and a boy who seems destined for the girl. The series also featured imaginative aircraft designs. |

|||

===Breakthrough films=== |

=== Breakthrough films === |

||

Miyazaki left |

Miyazaki left Nippon Animation in 1979, during the production of ''[[Anne of Green Gables (1979 TV series)|Anne of Green Gables]]'';{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=40}} he provided scene design and organization on the first fifteen episodes.{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=223}} He moved to Telecom Animation Film, a subsidiary of [[TMS Entertainment]], to direct his first feature anime film, ''[[The Castle of Cagliostro]]'' (1979), a ''Lupin III'' film.{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=50}} In his role at Telecom, Miyazaki helped train the second wave of employees.{{sfn|Miyazaki|1996|p=441}} Miyazaki directed six episodes of ''[[Sherlock Hound]]'' in 1981, until issues with Sir [[Arthur Conan Doyle]]'s estate led to a suspension in production; Miyazaki was busy with other projects by the time the issues were resolved, and the remaining episodes were directed by Koysuke Mikuriya. They were broadcast from November 1984 to May 1985.{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=225}} Miyazaki also wrote the graphic novel ''[[The Journey of Shuna]]'', inspired by the Tibetan folk talk "Prince who became a dog". The novel was published by Tokuma Shoten in June 1983,{{sfn|Miyazaki|1983|p=147}} and dramatised for radio broadcast in 1987.{{sfn|Kanō|2006|p=324}} ''[[Hayao Miyazaki's Daydream Data Notes]]'' was also irregularly published from November 1984 to October 1994 in ''Model Graphix'';{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=163}} selections of the stories received radio broadcast in 1995.{{sfn|Kanō|2006|p=324}} |

||

After the release of ''The Castle of Cagliostro'', Miyazaki began working on his ideas for an animated film adaptation of [[Richard Corben]]'s comic book ''Rowlf'' and pitched the idea to Yutaka Fujioka at TMS. In November 1980, a proposal was drawn up to acquire the film rights.{{sfn|Miyazaki|1996|p=249}}{{sfn|Kanō|2006|pp=37ff, 323}} Around that time, Miyazaki was also approached for a series of magazine articles by the editorial staff of ''Animage''. During subsequent conversations, he showed his sketchbooks and discussed basic outlines for envisioned animation projects with editors [[Toshio Suzuki]] and Osamu Kameyama, who saw the potential for collaboration on their development into animation. Two projects were proposed: {{Nihongo |''Warring States Demon Castle'' | 戦国魔城 | Sengoku ma-jō }}, to be set in the [[Sengoku period]]; and the adaptation of Corben's ''Rowlf''. Both were rejected, as the company was unwilling to fund anime projects not based on existing manga, and the rights for the adaptation of ''Rowlf'' could not be secured.{{sfn|Miyazaki|1996|p=146}}{{sfn|Miyazaki|2007|p=146}} An agreement was reached that Miyazaki could start developing his sketches and ideas into a manga for the magazine with the proviso that it would never be made into a film.{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=73—74}}{{sfn|Saitani|1995|p=9}} The manga—titled ''[[Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (manga)|Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind]]''—ran from February 1982 to March 1994. The story, as re-printed in the ''[[tankōbon]]'' volumes, spans seven volumes for a combined total of 1060 pages.{{sfn|Ryan}} Miyazaki drew the episodes primarily in pencil, and it was printed monochrome in sepia toned ink.{{sfn|Miyazaki|1996|p=94}}{{sfn|Miyazaki|2007|p=94}}{{sfn|Saitani|1995|p=9}} Miyazaki resigned from Telecom Animation Film in November 1982.{{sfn|Miyazaki|1996|p=442}} |

|||

Miyazaki's next film, ''[[Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (film)|Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind]]'', released on March 11, 1984, is an adaption of his manga series of the [[Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (manga)|same title]]. A science fiction adventure in which he introduces many of the recurring themes he would go on to explore throughout his career: a concern with [[ecology]], human interaction with and impact on, the environment; a fascination with aircraft and flight; pacifism, including an anti-military streak; feminism; morally ambiguous characterizations, especially among villains; and love. Starring the voices of [[Sumi Shimamoto]], [[Yōji Matsuda]], [[Iemasa Kayumi]], [[Gorō Naya]] and [[Yoshiko Sakakibara]], this was the first film both written and directed by Miyazaki. The film and the manga have common roots in ideas Miyazaki mulled over in the early 1980s. Serialization of the manga began in the February 1982 issue of [[Tokuma Shoten]]'s [[Animage]] magazine. The plot of the film corresponds roughly with the first 16 chapters of the manga. Miyazaki continued expanding the story over an additional decade after the release of the film. The successful cooperation on the creation of the manga and the film laid the foundation for other collaborative projects.<ref>{{cite book |ref=harv|last=Napier |first=Susan J. |title=The Worlds of Japanese Popular Culture: Gender, Shifting Boundaries and Global Culture |editor-last=Martinez|editor-first= Dolores P. |url=http://www.cambridge.org/gb/academic/subjects/anthropology/social-and-cultural-anthropology/worlds-japanese-popular-culture-gender-shifting-boundaries-and-global-cultures|publisher=Cambridge University Press |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20140302150406/http://www.cambridge.org/gb/academic/subjects/anthropology/social-and-cultural-anthropology/worlds-japanese-popular-culture-gender-shifting-boundaries-and-global-cultures |archivedate=March 2, 2014 |isbn=978-0521637299 |pages=91–109 |chapter=Vampires, Psychic Girls, Flying Women and Sailor Scouts |date=October 13, 1998|accessdate=November 8, 2014}}</ref>{{sfn|McCarthy| 1999 | page=45 }} |

|||

[[ |

[[Image:Nibariki (Hayao Miyazaki's personal studio, Butaya).jpg|thumb|right|upright=1|Miyazaki opened his own personal studio in 1984, named Nibariki.{{sfn|Miyazaki|1996|p=443}}]] |

||

In April 1984 the Nibariki office was started, in part, to manage copyrights. In June 1985, Miyazaki, Takahata and Tokuma Shoten chairman Yasuyoshi Tokuma founded the animation production company [[Studio Ghibli]] with funding from Tokuma Shoten. His first film with Ghibli, ''[[Castle in the Sky|Laputa: Castle in the Sky]]'' (1986) recounts the adventure of two orphans, voiced by [[Mayumi Tanaka]] and [[Keiko Yokozawa]], as they seek a magical castle-island that floats in the sky; ''[[My Neighbor Totoro]]'' (''Tonari no Totoro'', 1988) tells of the adventure of two girls, voiced by [[Noriko Hidaka]] and [[Chika Sakamoto]], and their interaction with forest spirits; and ''[[Kiki's Delivery Service]]'' (1989), adapted from the 1985 novel of the same name by [[Eiko Kadono]], tells the story of a small-town girl voiced by [[Minami Takayama]] who leaves home to begin life as a [[witch]] in a big city. Miyazaki's fascination with flight is evident throughout these films, ranging from the [[ornithopter]]s flown by pirates in ''Castle in the Sky'', to the Totoro and the Cat Bus soaring through the air, and Kiki flying her broom. |

|||

Following the success of ''Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind'', Yasuyoshi Tokuma, the founder Tokuma Shoten, encouraged Miyazaki to work on a film adaptation.{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=47}} Miyazaki initially refused, but agreed on the condition that he could direct.{{sfn|Hiranuma}} Miyazaki's imagination was sparked by the mercury poisoning of [[Minamata Bay]] and how nature responded and thrived in a poisoned environment, using it to create the film's polluted world. Miyazaki and Takahata chose the minor studio [[Topcraft]] to animate the film, as they believed its artistic talent could transpose the sophisticated atmosphere of the manga to the film.{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=47}} Pre-production began on May 31, 1983; Miyazaki encountered difficulties in creating the screenplay, with only sixteen chapters of the manga to work with.{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=75}} Takahata enlisted experimental and minimalist musician [[Joe Hisaishi]] to compose the film's score.{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|pp=77}} ''[[Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (film)|Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind]]'' was released on March 11, 1984. It grossed [[¥]]1.48 billion at the [[box office]], and made an additional ¥742 million in distribution income.{{sfn|Kanō|2006|pp=65–66}} It is often seen as Miyazaki's pivotal work, cementing his reputation as an animator.{{sfn|Osmond|1998|pp=57–81}}{{efn|{{harvtxt|Cavallaro|2006}} states: "''Nausicaä'' constitutes an unprecedented accomplishment in the world of Japanese animation — and one to which any contemporary Miyazaki aficionado ought to remain grateful given that it is precisely on the strength of its performance that Studio Ghibli was founded."{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=48}}}} It was lauded for its positive portrayal of women, particularly that of main character [[Nausicaä (character)|Nausicaä]].{{sfn|Moss|2014}}{{sfn|Nakamura|Matsuo|2002|p=73}}{{efn|name="Napier Nausicaa"|{{harvtxt|Napier|1998}} states: "Nausicaä ... possesses elements of the self-sacrificing sexlessness of [''[[Mai, the Psychic Girl]]''{{'}}s] Mai, but combines them with an active and resolute personality to create a remarkably powerful and yet fundamentally feminine heroine."{{sfn|Napier|1998|p=101}}}} Several critics have labeled ''Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind'' as possessing [[Anti-war movement|anti-war]] and [[Feminism|feminist]] themes; Miyazaki argues otherwise, stating that he only wishes to entertain.{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=89}}{{efn|Quoting Miyazaki, {{harvtxt|McCarthy|1999}} states: "I don't make movies with the intention of presenting any messages to humanity. My main aim in a movie is to make the audience come away from it happy."{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=89}}}} The successful cooperation on the creation of the manga and the film laid the foundation for other collaborative projects.{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=45}} In April 1984, Miyazaki opened his own office in Suginami Ward, naming it Nibariki.{{sfn|Miyazaki|1996|p=443}} |

|||

In 1992, Miyazaki directed ''[[Porco Rosso]]'', an adventure film set in the "[[Adriatic]]" during the 1920s. The film was a notable departure for Miyazaki, in that the main character was an adult man, an [[Fascism|anti-fascist]] aviator transformed into an [[anthropomorphic]] pig. The film is about a titular bounty hunter, voiced by Shūichirō Moriyama, and an American soldier of fortune, voiced by [[Akio Ōtsuka]]. The film explores the tension between selfishness and duty. ''Porco Rosso'' was released on July 19, 1992. That August, Studio Ghibli set up its headquarters in [[Koganei, Tokyo|Koganei]], [[Tokyo]].<ref name="JapanTimes">{{cite web|author=Matsutani, Minoru|url=http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/nn20080930i1.html|title=Japan's greatest film director?|work=[[Japan Times]]|date=September 30, 2008|accessdate=November 21, 2012}}</ref> |

|||

=== Studio Ghibli === |

|||

In 1995, Miyazaki began work on ''[[Princess Mononoke]]''. Starring the voices of [[Yuriko Ishida]], [[Yōji Matsuda]], [[Akihiro Miwa]] and [[Yūko Tanaka]], the story is about a struggle between the animal spirits inhabiting the forest and the humans exploiting the forest for industry, culminating in an uneasy co-existence and boundary transcending relationships between the main characters. In ''Mononoke'' he revisits the ecological and political themes and continues his cinematic exploration of the transience of existence he began in ''Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind''. Both films have their roots in ideas and artwork he created in the late 1970s and early 1980s but Helen McCarthy notes that Miyazaki's vision has developed, "from the utopian visions of ''Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind'' to the mature and kindly humanism of ''Princess Mononoke''".{{sfn|McCarthy| 1999 | pages= 199–203 }} The film was released on July 19, 1997 and was both a financial and critical success; it won the [[Japan Academy Prize (film)|Japan Academy Prize]] for Best Picture. Yvonne Tasker notes, "''Princess Mononoke'' marked a turning point in Miyazaki's career not merely because it broke Japanese box office records, but also because it, arguably, marked the emergence (through a distribution deal with Disney) into the global animation markets". Miyazaki went into semi-retirement after directing ''Princess Mononoke''. In working on the film, Miyazaki redrew 80,000 of the film's frames himself. He also stated at one point that ''Princess Mononoke'' would be his last film.<ref name="Tasker(2011)">{{cite book|last=Tasker|first=Yvonne|title=Fifty Contemporary Film Directors|year=2011|publisher=Routledge|location=London|pages=292–293}}</ref> Tokuma Shoten merged with Studio Ghibli that June.<ref name="JapanTimes"/> |

|||

==== Early films (1985–1996) ==== |

|||

In June 1985, Miyazaki, Takahata, Tokuma and Suzuki founded the animation production company [[Studio Ghibli]], with funding from Tokuma Shoten. Studio Ghibli's first film, ''[[Castle in the Sky|Laputa: Castle in the Sky]]'' (1986), employed the same production crew of ''Nausicaä''. Miyazaki's designs for the film's setting were inspired by [[Ancient Greek architecture|Greek architecture]] and "European urbanistic templates".{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=58}} Some of the architecture in the film was also inspired by a [[Wales|Welsh]] mining town; Miyazaki witnessed the [[UK miners' strike (1984–85)|mining strike]] upon his first visit to Wales in 1984, and admired the miners' dedication to their work and community.{{sfn|Brooks|2005}} ''Laputa'' was released on August 2, 1986. It was the highest-grossing animation film of the year in Japan.{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=58}} Miyazaki's following film, ''[[My Neighbor Totoro]]'', was released alongside Takahata's ''[[Grave of the Fireflies]]'' in April 1988 to ensure Studio Ghibli's financial status. The simultaneous production was chaotic for the artists, as they switched between projects.{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=68}}{{efn|Producer Toshio Suzuki stated: "The process of making these films at the same time in a single studio was sheer chaos. The studio's philosophy of not sacrificing quality was to be strictly maintained, so the task at hand seemed almost impossible. At the same time, nobody in the studio wanted to pass up the chance to make both of these films."{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=68}}}} ''My Neighbor Totoro'' features the theme of the relationship between the environment and humanity—a contrast to ''Nausicaä'', which emphasises technology's negative effect on nature.{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=70}} The film was commercially unsuccessful at the box office, though merchandising was successful, and it received critical acclaim.{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=194}}{{sfn|Camp|Davis|2007|p=227}} |

|||

In 1987, Studio Ghibli acquired the [[Film rights|rights]] to create a film adaptation of [[Eiko Kadono]]'s novel ''[[Kiki's Delivery Service (novel)|Kiki's Delivery Service]]''. Miyazaki's work on ''My Neighbor Totoro'' prevented him from directing the adaptation; [[Sunao Katabuchi]] was chosen as director, and Nobuyuki Isshiki was hired as script writer. Miyazaki's dissatisfaction of Isshiki's first draft led him to make changes to the project, ultimately taking the role of director. Kadono was unhappy with the differences between the book and the screenplay. Miyazaki and Suzuki visited Kadono and invited her to the studio; she allowed the project to continue.{{sfn|Macdonald|2014}} The film was originally intended to be a 60-minute special, but expanded into a feature film after Miyazaki completed the storyboards and screenplay.{{sfn|Miyazaki|2006|p=12}} ''[[Kiki's Delivery Service]]'' premiered on July 29, 1989. It earned ¥2.15 billion at the box office,{{sfn|Gaulène|2011}} and was the highest-grossing film in Japan in 1989.{{sfn|Hairston|1998}} |

|||

During this period of semi-retirement, Miyazaki spent time with the daughters of a friend. One of these friends would become his inspiration for Miyazaki's next film which would also become his biggest commercial success to date, ''[[Spirited Away]]''. The film stars the voices of [[Rumi Hiiragi]], [[Mari Natsuki]] and [[Miyu Irino]], and is the story of a girl, forced to survive in a bizarre spirit world, who works in a bathhouse for spirits after her parents are turned into pigs by the sorceress who owns it. The film was released in July 2001 and grossed [[Yen|¥]]30.4 billion (approximately $300 million) at the box office. Critically acclaimed, the film was considered one of the best films of the 2000s.<ref name="Metadecade">{{cite web|title=Film Critics Pick the Best Movies of the Decade|url=http://www.metacritic.com/feature/film-critics-pick-the-best-movies-of-the-decade|work=[[Metacritic]]|accessdate=September 4, 2012|date=January 3, 2010}}</ref> It won a [[Japan Academy Prize (film)|Japan Academy Prize]], a Golden Bear award at the 2002 [[Berlin International Film Festival]], and an [[Academy Award]] for [[Academy Award for Best Animated Feature|Best Animated Feature]]. In his book ''Otaku'', [[Hiroki Azuma]] observed: "Between 2001 and 2007, [[otaku]] forms and markets quite rapidly won social recognition in Japan", and cites Miyazaki's win at the Academy Awards for ''Spirited Away'' among his examples.<ref>{{cite book |last=Azuma |first=Hiroki |date=April 10, 2009 |title=Otaku |url=http://www.upress.umn.edu/book-division/books/otaku |location=Minneapolis |publisher=University of Minnesota Press | chapter= Preface |page = xi|isbn=978-0816653515 |accessdate=January 31, 2014}}</ref> |

|||

From March to May 1989, Miyazaki's manga ''[[Hikōtei Jidai]]'' was published in the magazine ''[[:fr:Model Graphix|Model Graphix]]''.{{sfn|Lamar|2010}} Miyazaki began production on a 45 minute in-flight film for [[Japan Airlines]] based on the manga; Suzuki ultimately extended the film into the feature-length film, titled ''[[Porco Rosso]]'', as expectations grew. Due to the end of production on Takahata's ''[[Only Yesterday (1991 film)|Only Yesterday]]'' (1991), Miyazaki initially managed the production of ''Porco Rosso'' independently.{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=96}} The outbreak of the [[Yugoslav Wars]] in 1991 had an impact on Miyazaki, prompting a more sombre tone for the film;{{sfn|Havis|2016}} Miyazaki would later refer to the film as "foolish", as its mature tones were unsuitable for children.{{sfn|Sunada|2013|loc=46:12}} The film featured [[Anti-war movement|anti-war]] themes, which Miyazaki would later revisit.{{sfn|Blum|2013}}{{efn|name="Akimoto Rosso"|{{harvtxt|Akimoto|2014}} states: "''Porco Rosso'' (1992) can be categorized as 'anti-war propaganda' ... the film conveys the important memory of war, especially the [[Interwar period|interwar era]] and the [[Post–Cold War era|post-Cold War world]]."{{sfn|Akimoto|2014}}}} The airline remained a major investor in the film, resulting in its initial premiere as an in-flight film, prior to its theatrical release on July 18, 1992.{{sfn|Havis|2016}} The film was critically and commercially successful,{{efn|Miyazaki was surprised by the success of ''Porco Rosso'', as he considered it "too idiosyncratic for a toddlers-to-old-folks general audience".{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=96}}}} remaining the highest-grossing animated film in Japan for several years.{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=96}}{{efn|''Porco Rosso'' was succeeded as the highest-grossing animated film in Japan by Miyazaki's ''[[Princess Mononoke]]'' in 1997.{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=96}}}} |

|||

===21st century=== |

|||

In July 2004, Miyazaki completed production on ''[[Howl's Moving Castle (film)|Howl's Moving Castle]]'', based on [[Diana Wynne Jones]]' 1986 [[fantasy]] [[Howl's Moving Castle|novel of the same name]]. Miyazaki came out of retirement following the sudden departure of [[Mamoru Hosoda]], the film's original director. The film premiered at the 2004 [[Venice International Film Festival]] and was later released on November 24, 2004, again to positive reviews. It won the [[Golden Osella]] award for animation technology, and received an Oscar nomination for Best Animated Feature. |

|||

Studio Ghibli set up its headquarters in [[Koganei, Tokyo|Koganei]], [[Tokyo]] in August 1992.{{sfn|Matsutani|2008}} In November 1992, two [[Television advertisement|television spots]] directed by Miyazaki were broadcast by [[Nippon TV|Nippon Television Network]] (NTV): ''Sora Iro no Tane'', a 90-second spot loosely based on the illustrated story ''The Sky Blue Seed'' by Reiko Nakagawa and Yuriko Omura, and commissioned to celebrate NTV's fortieth anniversary;{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=104}} and ''Nandarou'', aired as one 15-second and four 5-second spots, centered on an undefinable creature which ultimately became NTV's mascot.{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=105}} Miyazaki designed the storyboards and wrote the screenplay for ''[[Whisper of the Heart]]'' (1995), directed by [[Yoshifumi Kondō]].{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=114}}{{efn|{{harvtxt|Cavallaro|2006}} states: "[Kondō's] assocation with Miyazaki and Takahata dated back to their days together at A-Pro ... He would also have been Miyazaki's most likely successor had he not tragically passed away in 1998 at the age of 47, victim of an aneurysm."{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=114}}}} |

|||

In 2005, Miyazaki received a lifetime achievement award at the [[Venice Film Festival]]. On February 10, 2005, Studio Ghibli announced that it was ending its relationship with Tokuma Shoten. The studio moved its headquarters to [[Koganei, Tokyo]], and acquired the copyrights of Miyazaki's works and business rights from Tokuma Shoten.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.animenewsnetwork.com/news/2005-02-10/studio-ghibli-to-split-from-tokuma|title=Studio Ghibli to be Split from Tokuma|date=February 10, 2005|accessdate=November 21, 2012}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.yomiuri.co.jp/entertainment/ghibli/cnt_eventnews_20050215a.htm|script-title=ja:ジブリ、徳間書店から独立|language=Japanese|work=Yomiuri Shimbun|date=February 15, 2005|accessdate=November 21, 2012}}</ref> |

|||

==== Global emergence (1997–2008) ==== |

|||

In 2006, Miyazaki's son [[Gorō Miyazaki]] completed his first film, ''[[Tales from Earthsea (film)|Tales from Earthsea]]'', starring the voices of Jun'ichi Okada and [[Bunta Sugawara]] and based on several stories by [[Ursula K. Le Guin]]. Hayao Miyazaki had long aspired to make an anime of this work and had repeatedly asked for permission from the author, [[Ursula K. Le Guin]]. However, he had been refused every time. Instead, Miyazaki produced ''[[Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (film)|Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind]]'' and ''[[The Journey of Shuna|Shuna no Tabi]]'' (''The Journey of Shuna'') as substitutes (some of the ideas from ''Shuna no Tabi'' were diverted to this movie). When Le Guin finally requested that Miyazaki produce an anime adaptation of her work, he refused, because he had lost the desire to do so. Le Guin remembers this differently: "In August 2005, Mr. Toshio Suzuki of Studio Ghibli came with Mr. Hayao Miyazaki to talk with me and my son (who controls the trust which owns the ''Earthsea'' copyrights). We had a pleasant visit in my house. It was explained to us that Mr. Hayao wished to retire from filmmaking, and that the family and the studio wanted Mr. Hayao's son Gorō, who had never made a film at all, to make this one. We were very disappointed, and also anxious, but we were given the impression, indeed assured, that the project would be always subject to Mr. Hayao's approval. With this understanding, we made the agreement." Throughout the film's production, Gorō and his father were not speaking to each other, due to a dispute over whether or not Gorō was ready to direct.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://nausicaa.net/miyazaki/newspro/latestnews_headlines-archive-7-2006.html|title=Coranto Archive: July 3, 2006 Hayao Miyazaki's Surprise Visit|date=July 3, 2006|accessdate=February 19, 2007|publisher=[[Nausicaa.net]]}}</ref> It was originally to be produced by Miyazaki, but he declined as he was already in the middle of producing ''[[Howl's Moving Castle (film)|Howl's Moving Castle]]''. Ghibli decided to make Gorō, who had yet to head any animated films, the producer instead. ''Tales from Earthsea'' was released on July 29, 2006, to mixed reviews. |

|||

Miyazaki began work on the initial storyboards for ''[[Princess Mononoke]]'' in August 1994,{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=185}} based on preliminary thoughts and sketches from the late 1970s.{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=182}} While experiencing [[writer's block]] during production, Miyazaki accepted a request for the creation of ''[[On Your Mark]]'', a music video for the [[On Your Mark (song)|song of the same name]] by [[Chage and Aska]].{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|pp=211}} In the production of the video, Miyazaki experimented with computer animation to supplement traditional animation, a technique he would soon revisit for ''Princess Mononoke''.{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=113}} ''On Your Mark'' premiered as a short before ''Whisper of the Heart''.{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=112}} Despite the video's popularity, Suzuki said that it was not given "100 percent" focus.{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|pp=214}} |

|||

[[Image:Mononoke hime cgi.png|thumb|left|upright=1.2|Miyazaki employed the use of [[3D rendering]] in ''[[Princess Mononoke]]'' (1997) to create writhing "demon flesh" and composite them onto the hand-drawn characters. Approximately five minutes of the film uses similar techniques.{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=127}}]] |

|||

In 2006, [[Nausicaa.net]] reported Hayao Miyazaki's plans to direct another film, rumored to be set in [[Kobe]]. Among areas Miyazaki's team visited during pre-production were an old café run by an elderly couple, and the view of a city from high in the mountains. The exact location of these places was censored from Studio Ghibli's production diaries. The studio also announced that Miyazaki had begun creating storyboards for the film and that they were being produced in [[watercolor]] because the film would have an "unusual visual style". Studio Ghibli said the production time would be about 20 months, with release slated for Summer 2008. |

|||

In May 1995, Miyazaki took a group of artists and animators to the ancient forests of [[Yakushima]] and the mountains of [[Shirakami-Sanchi]], taking photographs and making sketches.{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=186}} The landscapes in the film were inspired by Yakushima.{{sfn|Ashcraft|2013}} In ''Princess Mononoke'', Miyazaki revisited the ecological and political themes of ''Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind''.{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=203}}{{efn|{{harvtxt|McCarthy|1999}} states: "From the Utopian idealism of ''Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind'', Miyazaki's vision has developed to encompass the mature and kindly humanism of ''Princess Mononoke''."{{sfn|McCarthy|1999|p=203}}}} Miyazaki supervised the 144,000 [[cel]]s in the film, about 80,000 of which were key animation.{{sfn|Toyama}}{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=126}} ''Princess Mononoke'' was produced with an estimated budget of ¥2.35 billion (approximately [[US$]]23.5 million),{{sfn|Karrfalt|1997}} making it the most expensive film by Studio Ghibli at the time.{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=120}} Approximately fifteen minutes of the film uses computer animation: about five minutes uses techniques such as [[3D rendering]], digital composition, and [[texture mapping]]; the remaining ten minutes uses [[Traditional animation#Digital ink and paint|digital ink and paint]]. While the original intention was to digitally paint 5,000 of the film's frames, time constraints doubled this.{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=127}} |

|||

In 2007, the film's title was publicly announced as ''[[Ponyo|Gake no ue no Ponyo]]'',<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ghibliworld.com/news.html#1903|title=Ghibli World|date=March 19, 2007|accessdate=March 19, 2007}}</ref> which was eventually retitled ''Ponyo'' for its international releases. The film stars the voices of Yuria Nara, Hiroki Doi, [[Tomoko Yamaguchi]], [[Kazushige Nagashima]], [[George Tokoro]] and [[Yūki Amami]]. Toshio Suzuki noted that "70 to 80% of the film takes place at sea. It will be a director's challenge on how they will express the sea and its waves with freehand drawing." ''Ponyo'' was released on July 19, 2008, to positive reviews and the film grossed $202 million worldwide. |

|||

Upon its premiere on July 12, 1997, ''Princess Mononoke'' was critically acclaimed, becoming the first animated film to win the [[Japan Academy Prize for Picture of the Year]].{{sfn|CBS News|2014|p=15}}{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=32}} The film was also commercially successful, earning a domestic total of ¥14 billion (US$148 million),{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=120}} and becoming the highest-grossing film in Japan for several months.{{sfn|Ebert|1999}}{{efn|name="Titanic"}} [[Miramax Films]] purchased the film's distributions rights for North America;{{sfn|Brooks|2005}} it was the first Studio Ghibli production to receive a substantial theatrical distribution in the United States. While it was largely unsuccessful at the box office, grossing about US$3 million,{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=121}} it was seen as the introduction of Studio Ghibli to global markets.{{sfn|Tasker|2011|p=292}}{{efn|{{harvtxt|Tasker|2011}} states: "''Princess Mononoke'' marked a turning point in Miyazaki's career not merely because it broke Japanese box office records, but also because it, arguably, marked the emergence (through a distribution deal with Disney) into the global animation markets."{{sfn|Tasker|2011|p=292}}}} Miyazaki claimed that ''Princess Mononoke'' would be his final film.{{sfn|Tasker|2011|p=292}} |

|||

Miyazaki later co-wrote the screenplay for Studio Ghibli's next film, ''[[Arrietty|The Secret World of Arrietty]]'', based on [[Mary Norton (author)|Mary Norton]]'s 1952 novel ''[[The Borrowers]]''. The film was the directorial debut of [[Hiromasa Yonebayashi]], a Ghibli animator. Starring the voices of [[Mirai Shida]], [[Ryunosuke Kamiki]], [[Tomokazu Miura]], [[Keiko Takeshita]], [[Shinobu Otake]] and [[Kirin Kiki]], the film focuses on a small family known as the Borrowers who must avoid detection when discovered by humans. The film was released on July 17, 2010, again to positive reviews, and grossed $145 million worldwide. In 2011, Miyazaki co-wrote ''[[From Up on Poppy Hill]]'', based on the 1980 [[Kokurikozaka kara|manga of the same name]] written by Tetsurō Sayama and illustrated by Chizuru Takahashi. The film stars the voices of [[Masami Nagasawa]], Junichi Okada, [[Shunsuke Kazama]] and [[Teruyuki Kagawa]]. Set in Yokohama, the film's story focuses on Umi Matsuzaki, a high school student who is forced to fend for herself when her sailor father goes missing from the seaside town. The film was released on July 16, 2011, once again to positive reviews. |

|||

Tokuma Shoten merged with Studio Ghibli in June 1997.{{sfn|Matsutani|2008}} Miyazaki's next film was conceived while on vacation at a mountain cabin with his family and five young girls who were family friends. Miyazaki realised that he had not created a film for ten-year-old girls, and set out to do so. He read [[shōjo manga]] magazines like ''[[Nakayoshi]]'' and ''[[Ribon]]'' for inspiration, but felt they only offered subjects on "crushes and romance", which is not what the girls "held dear in their hearts". He decided to produce the film about a female heroine whom they could look up to.{{sfn|Toyama|2001}} Production of the film, titled ''[[Spirited Away]]'', commenced in 2000 on a budget of ¥1.9 billion (US$15 million). As with ''Princess Mononoke'', the staff experimented with computer animation, but kept the technology at a level to enhance the story, not to "steal the show".{{sfn|Howe|2003a}} ''Spirited Away'' deals with symbols of human greed,{{sfn|Gold|2016}}{{efn|Regarding a letter written by Studio Ghibli which paraphrases Miyazaki, {{harvtxt|Gold|2016}} states: "Chihiro's parents turning into pigs symbolizes how some humans become greedy ... There were people that 'turned into pigs' during Japan's [[bubble economy]] of the 1980s, and these people still haven't realized they've become pigs."{{sfn|Gold|2016}}}} and a [[Liminality|liminal]] journey through the realm of spirits.{{sfn|Reider|2005|p=9}}{{efn|Protagonist Chihiro stands outside societal boundaries in the supernatural setting. The use of the word ''[[Spirit away|kamikakushi]]'' (literally "hidden by gods") within the Japanese title reinforces this symbol. {{harvtxt|Reider|2005}} states: "''Kamikakushi'' is a verdict of 'social death' in this world, and coming back to this world from ''Kamikakushi'' meant 'social resurrection'."{{sfn|Reider|2005|p=9}}}} The film was released on July 20, 2001; it received critical acclaim, and is considered among the greatest films of the 2000s.{{sfn|Dietz|2010}} It won the Japan Academy Prize for Picture of the Year,{{sfn|Howe|2003b}} and the [[Academy Award for Best Animated Feature]].{{sfn|Howe|2003c}} The film was also commercially successful, earning ¥30.4 billion (US$289.1 million) at the box office.{{sfn|Sudo|2014}} It is the highest-grossing film in Japan.{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=135}} |

|||

On December 13, 2012, Studio Ghibli announced that Miyazaki worked on his next film, ''[[The Wind Rises]]'', based on his manga of the same name, with plans to simultaneously release it with ''[[The Tale of the Princess Kaguya]]''.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://eiga.com/news/20121213/10/|script-title=ja:ジブリ新作2本!宮崎駿監督「風立ちぬ」と高畑勲監督「かぐや姫の物語」|language=Japanese|work=Eiga.com|date=December 13, 2012|accessdate=March 9, 2012}}</ref> The film stars the voices of [[Hideaki Anno]], Hidetoshi Nishijima, [[Masahiko Nishimura]] and [[Miori Takimoto]]. ''The Wind Rises'' tells the story of Jiro Horikoshi, designer of the [[Mitsubishi A6M Zero]] fighter aircraft that served in [[World War II]]. The film was released on July 20, 2013. |

|||

In September 2001, Studio Ghibli announced the production of ''[[Howl's Moving Castle (film)|Howl's Moving Castle]]'', based on the [[Howl's Moving Castle|novel]] by [[Diana Wynne Jones]].{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=157}} [[Mamoru Hosoda]] of Toei Animation was originally selected to direct the film,{{sfn|Schilling|2002}} but disagreements between Hosoda and Studio Ghibli executives led to the project's abandonment.{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=157}} After six months, Studio Ghibli resurrected the project. Miyazaki was inspired to direct the film upon reading Jones' novel, and was struck by the image of a castle moving around the countryside; the novel does not explain how the castle moved, which led to Miyazaki's designs.{{sfn|Talbot|2005}} He travelled to [[Colmar]] and [[Riquewihr]] in [[Alsace]], France, to study the architecture and the surroundings for the film's setting.{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=167}} Additional inspiration came from the concepts of future technology in [[Albert Robida]]'s work,{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=168}} as well as the "illusion art" of 19th century Europe.{{sfn|Cavallaro|2015|p=145}}{{efn|Quoting producer Toshio Suzuki, {{harvtxt|Cavallaro|2015}} states: {{nowrap|"[Miyazaki]}} is said to feel instinctively drawn back to the sorts of artists who 'drew "illusion art" in Europe back then... They drew many pictures imagining what the 20th century would look like. They were illusions and were never realized at all.' What Miyazaki recognizes in these images is their unique capacity to evoke 'a world in which science exists as well as magic, since they are illusion'."{{sfn|Cavallaro|2015|p=145}}}} The film was produced digitally, but the characters and backgrounds were drawn by hand prior to being digitized.{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=165}} It was released on November 20, 2004, and received widespread critical acclaim. The film received the Osella Award for Technical Excellence at the [[61st Venice International Film Festival]],{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=157}} and was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature.{{sfn|Wellham|2016}} In Japan, the film grossed a record $14.5 million in its first week of release.{{sfn|Talbot|2005}} It remains among the highest-grossing films in Japan, with a worldwide gross of over ¥19.3 billion.{{sfn|Osaki|2013}} Miyazaki received the honorary Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement award at the [[62nd Venice International Film Festival]] in 2005.{{sfn|Cavallaro|2006|p=157}} |

|||

On September 1, 2013, numerous Japanese television networks, including [[NHK]], reported on the announcement, at the [[Venice Film Festival]], by Ghibli President Koji Hoshino, that Miyazaki was retiring from creating feature-length animated films. Miyazaki confirmed his retirement during a press conference, in Tokyo, on September 6, 2013.<ref name="Anime News Network"/><ref>{{cite web| last=Akagawa | first=Roy | title=Excerpts of Hayao Miyazaki's news conference announcing his retirement| date=September 6, 2013 | url=http://ajw.asahi.com/article/behind_news/people/AJ201309060087 | website= Asahi Shimbun | accessdate=February 5, 2014 }}</ref><!--Miyazaki himself did not appear on a Radio Show on New Year's Eve, December 31, 2013, see retirement section and talk page--> |

|||

In March 2005, Studio Ghibli split from Tokuma Shoten.{{sfn|Anime News Network|2005}} In the 1980s, Miyazaki contacted [[Ursula K. Le Guin]] expressing interest in producing an adaptation of her ''[[Earthsea]]'' novels; unaware of Miyazaki's work, Le Guin declined. Upon watching ''My Neighbor Totoro'' several years later, Le Guin expressed approval to the concept of the adaptation. She met with Suzuki in August 2005, who wanted Miyazaki's son [[Gorō Miyazaki|Gorō]] to direct the film, as Miyazaki had wished to retire. Disappointed that Miyazaki was not directing, but under the impression that he would supervise his son's work, Le Guin approved of the film's production.{{sfn|Le Guin|2006}} Miyazaki later publicly opposed and criticized Gorō's appointment as director.{{sfn|Collin|2013}} Upon Miyazaki's viewing of the film, he wrote a message for his son: "It was made honestly, so it was good".{{sfn|G. Miyazaki|2006b}} |

|||

Despite Miyazaki's retirement, it was reported that he is developing a short film, ''Boro the Caterpillar'', which will be screened exclusively at the [[Studio Ghibli Museum]] in [[Mitaka, Tokyo]] in July 2017.<ref>{{cite web| title=Hayao Miyazaki's New Anime Short Debuts in July, But His Proposed Feature Film Will Not Debut in 2019| date=April 29, 2017| url=https://www.animenewsnetwork.com/news/2017-04-29/hayao-miyazaki-new-anime-short-debuts-in-july-but-his-proposed-feature-film-will-not-debut-in-2019/.115480| website=Wired Anime News Network| accessdate=April 30, 2017}}</ref> |

|||

Miyazaki designed the covers for several manga novels in 2006, including ''A Trip to Tynemouth''; he also worked as editor, and created a short manga for the book.{{sfn|Miyazaki|2009|pp=398–401}} Miyazaki's next film, ''[[Ponyo]]'', began production in May 2006.{{sfn|Miyazaki|2013|p=16}} It was initially inspired by "[[The Little Mermaid]]" by [[Hans Christian Andersen]], though began to take its own form as production continued.{{sfn|Castro|2012}} Miyazaki aimed for the film to celebrate the innocence and cheerfulness of a child's universe. He intended for it to only use traditional animation,{{sfn|Miyazaki|2013|p=16}} and was intimately involved with the artwork. He preferred to draw the sea and waves himself, as he enjoyed experimenting.{{sfn|Ghibli World|2007}} ''Ponyo'' features 170,000 frames—a record for Miyazaki.{{sfn|Sacks|2009}} The film's seaside village was inspired by [[Tomonoura]], a town in [[Setonaikai National Park]], where Miyazaki stayed in 2005.{{sfn|''Yomiuri Shimbun''|2008}} The main character is based on Gorō.{{sfn|Ball|2008}} Following its release on July 19, 2008, ''Ponyo'' was critically acclaimed, receiving Animation of the Year at the [[32nd Japan Academy Prize]].{{sfn|Anime News Network|2009}} The film was also a commercial success, earning ¥10 billion (US$93.2 million) in its first month{{sfn|Ball|2008}} and ¥15.5 billion by the end of 2008, placing it among the highest-grossing films in Japan.{{sfn|Landreth|2009}} |

|||

On November 13, 2016, Miyazaki reported that he proposed a new feature-length film that August. Miyazaki also remarked that he would continue working on short films for the [[Studio Ghibli Museum]].<ref name="Anime News Network (2016)">[http://www.animenewsnetwork.com/news/2016-11-13/hayao-miyazaki-working-on-proposed-new-anime-feature-film/.108775 Hayao Miyazaki Working on Proposed New Anime Feature Film], Anime News Network. Retrieved November 13, 2016.</ref> It was also announced that production of his upcoming "last film" project will begin in October this year and is now looking for animators and background artists to work on a three-year contract.<ref name="lastfilm">{{cite news|publisher=Ani.me|url=https://ani.me/posts/2970-Hayao-Miyazaki-s-Final-Film-to-Start-Production-in-October-Studio-Ghibli-now-Hiring-Animators-|title=Hayao Miyazaki’s “Final Film” to Start Production in October- Studio Ghibli now Hiring Animators !|author=Serena Rei}}</ref> |

|||

==== Final films (2009–2013) ==== |

|||

==Manga career== |

|||

[[File:HayaoMiyazakiCCJuly09.jpg|thumb|190px|right|Miyazaki at the 2009 [[San Diego Comic-Con]].]] |

|||

{{Main article|Works of Hayao Miyazaki#Manga works}} |

|||

In early 2009, Miyazaki began writing a manga called {{Nihongo|''Kaze Tachinu''|風立ちぬ|The Wind Rises}}, telling the story of [[Mitsubishi A6M Zero]] fighter designer [[Jiro Horikoshi]]. The manga was first published in two issues of the Model Graphix magazine, published on February 25 and March 25, 2009.{{sfn|Animekon|2009}} Miyazaki later co-wrote the screenplay for ''[[Arrietty]]'' (2010) and ''[[From Up on Poppy Hill]]'', directed by [[Hiromasa Yonebayashi]] and Gorō Miyazaki, respectively.{{sfn|Cavallaro|2014|p=183}} Miyazaki wanted his next film to be a sequel to ''Ponyo'', but Suzuki convinced him to instead adapt ''Kaze Tachinu'' to film.{{sfn|Anime News Network|2014b}} In November 2012, Studio Ghibli announced the production of ''[[The Wind Rises]]'', based on ''Kaze Tachinu'', to be released alongside Takahata's ''[[The Tale of Princess Kaguya]]''.{{sfn|Armitage|2012}} |

|||

Miyazaki never abandoned his childhood dream of becoming a manga artist. His professional career in this medium begins in 1969 with the publication of his manga interpretation of ''Puss in Boots''. Serialized in 12 chapters in the Sunday edition of [[Tokyo Shimbun]], from January to March 1969. Printed in colour and created for promotional purposes in conjunction with his work on Yabuki's animated film. |

|||

Miyazaki was inspired to create ''The Wind Rises'' after reading a quote from Horikoshi: "All I wanted to do was to make something beautiful".{{sfn|Keegan|2013}} Several scenes in ''The Wind Rises'' were inspired by [[Tatsuo Hori]]'s novel {{Nihongo|''[[The Wind Has Risen]]''|風立ちぬ}}, in which Hori wrote about his life experiences with his fiancée before she died from tuberculosis. The female lead character's name, Naoko Satomi, was borrowed from Hori's novel {{Nihongo|''Naoko''|菜穂子}}.{{sfn|''Newtype''|2011|p=93}} ''The Wind Rises'' continues to reflect Miyazaki's pacifist stance,{{sfn|Keegan|2013}} continuing the themes of his earlier works, despite stating that condemning war was not the intention of the film.{{sfn|Foundas|2013}}{{efn|{{harvtxt|Foundas|2013}} states: "''The Wind Rises'' continues the strong pacifist themes of [Miyazaki's] earlier ''Nausicaä'' and ''Princess Mononoke'', marveling at man's appetite for destruction and the speed with which new technologies become weaponized."{{sfn|Foundas|2013}}}} The film premiered on July 20, 2013,{{sfn|Keegan|2013}} and received critical acclaim; it was named Animation of the Year at the [[37th Japan Academy Prize]],{{sfn|Green|2014}} and was nominated for Best Animated Feature at the [[86th Academy Awards]].{{sfn|Anime News Network|2014a}} It was also commercially successful, grossing ¥11.6 billion (US$110 million) at the Japanese box office, becoming the highest-grossing film in Japan in 2013.{{sfn|Ma|2014}} |

|||

That same year [[Pseudonymity|pseudonymous]] serialization started of Miyazaki's original manga ''[[Sabaku no Tami|People of the Desert]]''. Created in the style of illustrated stories he read, in boys' magazines and [[Tankōbon]] volumes, while growing up, such as Soji Yamakawa's {{Nihongo|''Shōnen ōja''|少年王者 |shōnen ōja}} and in particular Tetsuji Fukushima's {{Nihongo|''Evil Lord of the Desert''|沙漠の魔王|Sabaku no maō}}. Miyazaki's ''Desert People'' is a continuation of that tradition and a precursor for his own creations ''Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind'' and ''The Journey of Shuna''. In ''People of the Desert'' [[Exposition (narrative)|expository]] text is presented separately from the monochrome artwork with additional text balloons inside the panels for dialogue. 26 chapters were serialized in {{Nihongo|''Boys and Girls Newspaper''|少年少女新聞 |Shōnen shōjo shinbun}} between September 12, 1969 (Issue 28) and March 15, 1970 (issue 53). Published under the pseudonym {{Nihongo|Akitsu Saburō|秋津三朗}}. His manga interpretation of ''Animal Treasure Island'', made in conjunction with Ikeda's animated film, was serialized in the Sunday edition of Tokyo Shimbun from January to March 1971. (13 chapters, in colour).{{efn|McCarthy(1999){{sfn|McCarthy| 1999 | page=27, 219 }} Comic Box (1982), pp. 80 and pp. 111.<ref name="Comic_Box_JPN(1982)"/> July 1983 issue of ''Animage'', page 172.<ref>{{cite journal |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> | title=ナウシカの道 連載 1 宮崎駿・マンガの系譜 | trans_title= The Road to Nausicaä, chapter 1, Hayao Miyazaki’s Manga Genealogy | url=http://animage.jp | journal=Animage | location=Tokyo |publisher=Tokuma Shoten | issue=61 | date=June 10, 1983 | pages=172–173 | accessdate=November 27, 2013}}</ref> Takekuma, Kentaro, Lecture series at [[Kyoto Seika University]].<ref name="Takekuma(2008)">{{cite web| last=Takekuma | first=Kentaro | title=「マンガとアニメーションの間に」第4回「マンガ版『ナウシカ』はなぜ読みづらいのか?」| trans_title=Lecture series ''Between Manga and Anime'', Fourth lecture ''Why is the manga edition of Nausicaä so difficult to read?'' | date=October 30, 2008 | url=http://info.kyoto-seika.ac.jp/lecture/2008/10/102930.html | website=Kyoto Seika University | accessdate=December 11, 2013}}</ref> Re-release announcement in Asahi Shinbun for Fukushima's graphic novel.<ref name="Kaku(2012)">{{cite web| last=Kaku | first=Yoshiko | title=Classic graphic novel beloved by manga greats gets reprinted | date=October 11, 2012 | url=http://ajw.asahi.com/article/cool_japan/culture/AJ201210110055 | website= Asahi Shimbun | accessdate=December 11, 2013 }}</ref> }} |

|||

==== Focus on short films and manga (2013–present) ==== |

|||

His major work in the manga format is ''[[Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (manga)|Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind]]'', created intermittently from 1981 through 1994. In Japan it was first serialized in Tokuma Shoten's monthly magazine ''Animage'' and has been collected, after slight modification, in seven [[tankōbon]] volumes, spanning 1060 pages. ''Nausicaä'' has been translated and released outside Japan and has sold millions of copies worldwide. On March 11, 1984, the anime film of the same title was released. The characters and settings of manga and film have their common roots in the image boards Miyazaki created to visualise his ideas in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The anime is an amalgamation of the first sixteen chapters of the manga. In the manga Miyazaki explores the themes at greater length and in greater depth with a greater host of characters and a more expansive universe which he continued to expand over an additional decade after the release of the film. ''Nausicaä'' panels were printed monochrome in sepia-toned ink. |

|||

In September 2013, Miyazaki announced that he was retiring from the production of feature films due to his age, but wished to continue working on the displays at the [[Studio Ghibli Museum]].{{sfn|Anime News Network|2013a}}{{sfn|Akagawa|2013}} Miyazaki was awarded the [[Academy Honorary Award]] at the [[Governors Awards]] in November 2014.{{sfn|CBS News|2014|p=24}} He is currently developing ''Boro the Caterpillar'', a computer-animated short film which was first discussed during pre-production for ''Princess Mononoke''.{{sfn|''The Birth of Studio Ghibli''|2005|loc=24:47}} It will be screened exclusively at the Studio Ghibli Museum in July 2017.{{sfn|Anime News Network|2017}} He is also working on an untitled samurai manga.{{sfn|Anime News Network|2013b}} In August 2016, Miyazaki proposed a new feature-length film. He began animation work on the project without receiving official approval. He predicts that the film may be complete by 2019,{{sfn|Anime News Network|2016}} though Suzuki doubts this.{{sfn|Anime News Network|2017}} |

|||

== Personal life == |

|||

Other works include ''The Journey of Shuna'', released in 1983, and ''[[Hikōtei Jidai]]'', first serialized in ''Model Graphix'' in 1989. Both were created in watercolour. The latter was the basis of ''Porco Rosso''. [[Hayao Miyazaki's Daydream Data Notes]] contains short manga, essays and samples from Miyazaki's sketchbooks, bundled in book form in 1992.''Shuna'', in 1987, and selections from ''Daydream Data Notes'', in 1995, were dramatised for radio broadcast.<ref name="Kano(2006)">{{cite book |last=Kanō |first=Seiji |date=January 1, 2007 | origyear=first published March 31, 2006 |script-title=ja:宮崎駿全書 |trans_title=The Complete Hayao Miyazaki | language=Japanese |url= http://filmart.co.jp/books/filmmaker/2006-9-12tue-121/|location=Tokyo |publisher=Film Art Inc. |edition=2nd | page=324 | isbn=978-4-8459-0687-1 |accessdate=December 18, 2013 }}</ref> |

|||

Miyazaki married fellow animator Akemi Ota in October 1965. The couple have two sons: [[Gorō Miyazaki|Gorō]], born in January 1967, and Keisuke, born in April 1969.{{sfn|Miyazaki|1996|p=438}} Miyazaki's dedication to his work impacted negatively on his relationship with Gorō, as he was often absent. Gorō watched his father's works in an attempt to "understand" him, since the two rarely talked. During the production of ''Tales from Earthsea'' in 2006, Gorō said that his father "gets zero marks as a father but full marks as a director of animated films".{{sfn|G. Miyazaki|2006a}} |

|||

== Views == |

|||