Ordination of women: Difference between revisions

→Latter-day Saints: woops |

|||

| Line 166: | Line 166: | ||

In 2012-2013 the General Conference assembled several committees to study the issue and make a recommendation to be voted at the 2015 world General Conference session.<ref>About the Theology of Ordination Study Committee. http://www.adventistarchives.org/about-tosc#.UifKprx6_XY</ref> |

In 2012-2013 the General Conference assembled several committees to study the issue and make a recommendation to be voted at the 2015 world General Conference session.<ref>About the Theology of Ordination Study Committee. http://www.adventistarchives.org/about-tosc#.UifKprx6_XY</ref> |

||

On October 27th, 2013, Sandra Roberts became the first woman to lead a Seventh-day Adventist conference when she was elected as president of the Southeastern California Conference. <ref>http://blog.pe.com/multicultural-empire/2013/10/27/religion-coronas-sandra-roberts-makes-adventist-history/</ref> However, the worldwide Seventh-day Adventist church did not recognize this because presidents of conferences must be ordained pastors and the worldwide church did not recognize the ordination of women. <ref>http://blog.pe.com/multicultural-empire/2013/10/27/religion-coronas-sandra-roberts-makes-adventist-history/</ref> |

|||

As Protestant Christians who accept the Bible as their only rule of faith and practice, Seventh-day Adventists on both sides of the issue employ the same Bible texts and arguments used by other Protestants (e.g. 1 Tim. 2:12 and Gal. 3:28), but the fact that the most prominent and authoritative co-founder of the church—[[Ellen White]]—was a woman, also affects the discussion. Proponents of ordaining women point out that Adventists believe that Ellen White was chosen by God as a leader, preacher and teacher; that she remains the highest authority, outside the Bible, in the Seventh-day Adventist Church today; that she was regularly issued ordination credentials, which she carried without objection; and that she supported the ordination of women to at least some ministry roles. Opponents argue that because she was a prophet her example does not count, and that although she said she was ordained by God, she was never ordained in the ordinary way, by church leaders.<ref>(Source: Ministry Magazine, Dec 1988, Feb 1989, article: Ellen G. White and Women in ministry by William Fagal)</ref> |

As Protestant Christians who accept the Bible as their only rule of faith and practice, Seventh-day Adventists on both sides of the issue employ the same Bible texts and arguments used by other Protestants (e.g. 1 Tim. 2:12 and Gal. 3:28), but the fact that the most prominent and authoritative co-founder of the church—[[Ellen White]]—was a woman, also affects the discussion. Proponents of ordaining women point out that Adventists believe that Ellen White was chosen by God as a leader, preacher and teacher; that she remains the highest authority, outside the Bible, in the Seventh-day Adventist Church today; that she was regularly issued ordination credentials, which she carried without objection; and that she supported the ordination of women to at least some ministry roles. Opponents argue that because she was a prophet her example does not count, and that although she said she was ordained by God, she was never ordained in the ordinary way, by church leaders.<ref>(Source: Ministry Magazine, Dec 1988, Feb 1989, article: Ellen G. White and Women in ministry by William Fagal)</ref> |

||

Revision as of 15:55, 28 October 2013

The ordination of women to priestly office is a regular practice among some major religious groups of the present time, as it was of several religions of antiquity.

It remains a controversial issue in certain religions or denominations where the ordination, the process by which a person is consecrated and set apart for the administration of various religious rites, or where the role that an ordained person fulfills, has traditionally been restricted to men. That traditional restriction might have been due to cultural prohibition or theological doctrine, or both.

In some cases women have been permitted to be ordained, but not to hold higher positions, such as that of bishop in the Church of England.[1] Where laws prohibit sex discrimination in employment, exceptions are often made for religious organisations.

Antiquity

Sumer and Akkad

- Sumerian and Akkadian EN were top-ranking priestesses distinguished by special ceremonial attire and holding equal status to high priests. They owned property, transacted business, and initiated the hieros gamos ceremony with priests and kings.[2] Enheduanna (2285–2250 BCE), an Akkadian woman, was the first known holder of the title "EN Priestess".[3]

- Ishtaritu were temple prostitutes who specialized in the arts of dancing, music, and singing and served in the temples of Ishtar.[4]

- Puabi was a NIN, an Akkadian priestess of Ur in the 26th century BCE.

- Nadītu served as priestesses in the temples of Inanna in the ancient city of Uruk. They were recruited from the highest families in the land and were supposed to remain childless; they owned property and transacted business.

- In Sumerian epic texts such as Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, Nu-Gig were priestesses in temples dedicated to Inanna, or may be a reference to the goddess herself.[5]

- Qadishtu, Hebrew Qedesha (קדשה) or Kedeshah,[6] derived from the root Q-D-Š,[7][8] are mentioned in the Hebrew Bible as sacred prostitutes usually associated with the goddess Asherah.

- In the Epic of Gilgamesh, Shamhat tamed wild Enkidu with sexual intercourse after "six days and seven nights."

Ancient Egypt

In Ancient Egyptian religion, God's Wife of Amun was the highest ranking priestess; this title was held by a daughter of the High Priest of Amun, during the reign of Hatshepsut, while the capital of Egypt was in Thebes during the second millennium BC (circa 2160 BC).

Later, Divine Adoratrice of Amun was a title created for the chief priestess of Amun. During the first millennium BC, when the holder of this office exercised her largest measure of influence, her position was an important appointment facilitating the transfer of power from one pharaoh to the next, when his daughter was adopted to fill it by the incumbent office holder. The Divine Adoratrice ruled over the extensive temple duties and domains, controlling a significant part of the ancient Egyptian economy.

Ancient Egyptian priestesses:

- Gautseshen

- Henutmehyt

- Henuttawy

- Hui

- Iset

- Karomama Meritmut

- Maatkare Mutemhat

- Meritamen

- Neferhetepes is the earliest attested priestess of Hathor.[9]

- Neferure

- Tabekenamun a priestess of Hathor as well as a priestess of Neith.

Ancient Greece

In ancient Greek religion, some important observances, such as the Thesmophoria, were made by women. Priestesses played a major role in the Eleusinian Mysteries. The Gerarai were priestesses of Dionysus who presided over festivals and rituals associated with the god. A body of priestesses might also maintain the cult at a particular holy site, such as the Peleiades at the oracle of Dodona. The Arrephoroi were young girls ages seven to twelve who work as servantss of Athena Polias on the Athenian Acropolis and were charged with conducting unique rituals.

Women priestesses served as oracles at several sites, the most famous of which is the Oracle of Delphi. The priestess of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi was the Pythia, credited throughout the Greco-Roman world for her prophecies, which gave her a prominence unusual for a woman in male-dominated ancient Greece. The Phrygian Sibyl presided over an oracle of Apollo in Anatolian Phrygia. The inspired speech of divining women, however, was interpreted by male priests; a woman might be a mantic (mantis) who became the mouthpiece of a deity through possession, but the "prophecy of interpretation" required specialized knowledge and was considered a rational process suited only for a men '"prophet" (prophētēs).[10][11]

Ancient Rome

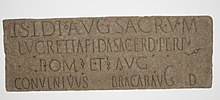

The Latin word sacerdos, "priest," is the same for both the grammatical genders. In Roman state religion, the priesthood of the Vestals was responsible for the continuance and security of Rome as embodied by the sacred fire that they could not allow to go out. The Vestals were a college of six sacerdotes (plural) devoted to Vesta, goddess of the hearth, both the focus of a private home (domus) and the state hearth that was the center of communal religion. Freed of the usual social obligations to marry and rear children, the Vestals took a vow of chastity in order to devote themselves to the study and correct observance of state rituals that were off-limits to the male colleges of priests.[12] They retained their religious authority until the Christian emperor Gratian confiscated their revenues[13] and his successor Theodosius I closed the Temple of Vesta permanently.[14]

The Romans also had at least two priesthoods that were each held jointly by a married couple, the rex and regina sacrorum, and the flamen and flaminica Dialis. The regina sacrorum ("queen of the sacred rites") and the flaminica Dialis (high priestess of Jupiter) each had her own distinct duties and presided over public sacrifices, the regina on the first day of every month, and the flaminica every nundinal cycle (the Roman equivalent of a week). The highly public nature of these sacrifices, like the role of the Vestals, indicates that women's religious activities in ancient Rome were not restricted to the private or domestic sphere.[15] So essential was the gender complement to these priesthoods that if the wife died, the husband had to give up his office. This is true of the flaminate, and probably true of the rex and regina.[15]

The title sacerdos was often specified in relation to a deity or temple,[16][15] such as a sacerdos Cereris or Cerealis, "priestess of Ceres", an office never held by men.[17] Female sacerdotes played a leading role in the sanctuaries of Ceres and Proserpina in Rome and throughout Italy that observed so-called "Greek rite" (ritus graecus). This form of worship had spread from Sicily under Greek influence, and the Aventine cult of Ceres in Rome was headed by male priests.[18] Only women celebrated the rites of the Bona Dea ("Good Goddess"), for whom sacerdotes are recorded.[19]

From the Mid Republic onward, religious diversity became increasingly characteristic of the city of Rome. Many religions that were not part of Rome's earliest state religion offered leadership roles as priests for women, among them the imported cult of Isis and of the Magna Mater ("Great Mother", or Cybele). An epitaph preserves the title sacerdos maxima for a woman who held the highest priesthood of the Magna Mater's temple near the current site of St. Peter's Basilica.[21] Inscriptions for the Imperial era record priestesses of Juno Populona and of deified women of the Imperial household.[15]

Under some circumstances, when cults such as mystery religions were introduced to Romans, it was preferred that they be maintained by women. Although it was Roman practice to incorporate other religions instead of trying to eradicate them,[22] the secrecy of some mystery cults was regarded with suspicion. In 189 BCE, the senate attempted to suppress the Bacchanals, claiming the secret rites corrupted morality and were a hotbed of political conspiracy. One provision of the senatorial decree was that only women should serve as priests of the Dionysian religion, perhaps to guard against the politicizing of the cult,[23] since even Roman women who were citizens lacked the right to vote or hold political office. Priestesses of Liber, the Roman god identified with Dionysus, are mentioned by the 1st-century BC scholar Varro, as well as indicated by epigraphic evidence.[15]

Other religious titles for Roman women include magistra, a high priestess, female expert or teacher; and ministra, a female assistant, particularly one in service to a deity. A magistra or ministra would have been responsible for the regular maintenance of a cult. Epitaphs provide the main evidence for these priesthoods, and the woman is often not identified in terms of her marital status.[16][15]

Hinduism

Gargi Vachaknavi is one of the earliest known woman sage form the Vedic period. Gargi composed several hymns that questioned the origin of all existence.[24][25] She is mentioned in the Sixth and the Eighth Brahmana of Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, where the brahmayajna, a philosophic congress organized by King Janaka of Videha is described, she challenged the sage Yajnavalkya with perturbing questions on the atman (soul).[26]

Bhairavi Brahmani is a guru of Sri Ramakrishna .She initiated Ramakrishna into Tantra.Under her guidance, Ramakrishna went through sixty four major tantric sadhanas which were completed in 1863.[27]

Ramakrishna Sarada Mission is the modern 21st century monastic order for women.The math was conducted under the guidance of the Ramakrishna monks until 1959, at which time it became entirely independent. It currently has centers in various parts of India, as also in Sydney, Australia.

There are two types of Hindu priests, purohits and pujaris. Both women and men are ordained as purohits and pujaris.[28][29] Chanda Vyas, born in Kenya, was Britain's first female Hindu priest.[30]

Furthermore, both men and women are Hindu gurus.[31] Shakti Durga, formerly known as Kim Fraser, was Australia's first female guru.[32]

Buddhism

The tradition of the ordained monastic community in Buddhism (the sangha) began with the Buddha, who established an order of monks.[35] According to the scriptures,[36] later, after an initial reluctance, he also established an order of nuns. Fully ordained Buddhist nuns are called bhikkhunis.[37][38] Mahapajapati Gotami, the aunt and foster mother of Buddha, was the first bhikkhuni.[39]

Prajñādhara is the twenty-seventh Indian Patriarch of Zen Buddhism and is believed to have been a woman.[40]

In the Mahayana tradition during the 13th century, the Japanese Mugai Nyodai became the first female abbess and thus the first ordained female Zen master.[41]

However, the bhikkhuni ordination once existing in the countries where Theravada is more widespread died out around the 10th century, and novice ordination has also disappeared in those countries. Therefore, women who wish to live as nuns in those countries must do so by taking eight or ten precepts. Neither laywomen nor formally ordained, these women do not receive the recognition, education, financial support or status enjoyed by Buddhist men in their countries. These "precept-holders" live in Burma, Cambodia, Laos, Nepal, and Thailand. In particular, the governing council of Burmese Buddhism has ruled that there can be no valid ordination of women in modern times, though some Burmese monks disagree. Japan is a special case as, although it has neither the bhikkhuni nor novice ordinations, the precept-holding nuns who live there do enjoy a higher status and better education than their precept-holder sisters elsewhere, and can even become Zen priests.[42] In Tibet there is currently no bhikkhuni ordination, but the Dalai Lama has authorized followers of the Tibetan tradition to be ordained as nuns in traditions that have such ordination.

The bhikkhuni ordination of Buddhist nuns has always been practiced in East Asia.[43] In 1996, through the efforts of Sakyadhita, an International Buddhist Women Association, ten Sri Lankan women were ordained as bhikkhunis in Sarnath, India.[44] Also, bhikkhuni ordination of Buddhist nuns began again in Sri Lanka in 1998 after a lapse of 900 years.[45] In 2003 Ayya Sudhamma became the first American-born woman to receive bhikkhuni ordination in Sri Lanka.[38] Furthermore, on February 28, 2003, Dhammananda Bhikkhuni, formerly known as Chatsumarn Kabilsingh, became the first Thai woman to receive bhikkhuni ordination as a Theravada nun (Theravada is a school of Buddhism).[46] Dhammananda Bhikkhuni was ordained in Sri Lanka.[47] A 55-year-old Thai Buddhist 8-precept white-robed maechee nun, Varanggana Vanavichayen, became the first woman to receive the going-forth ceremony of a Theravada novice (and the gold robe) in Thailand, in 2002.[48] Since then, the Thai Senate has reviewed and revoked the secular law passed in 1928 banning women's full ordination in Buddhism as unconstitutional for being counter to laws protecting freedom of religion. However Thailand's two main Theravada Buddhist orders, the Mahanikaya and Dhammayutika Nikaya, have yet to officially accept fully ordained women into their ranks.

In 2009 in Australia four women received bhikkhuni ordination as Theravada nuns, the first time such ordination had occurred in Australia.[49]

In 1997 Dhamma Cetiya Vihara in Boston was founded by Ven. Gotami of Thailand, then a 10 precept nun; when she received full ordination in 2000, her dwelling became America's first Theravada Buddhist bhikkhuni vihara. In 1998 Sherry Chayat, born in Brooklyn, became the first American woman to receive transmission in the Rinzai school of Buddhism.[50][51][52] In 2006 Merle Kodo Boyd, born in Texas, became the first African-American woman ever to receive Dharma transmission in Zen Buddhism.[53] Also in 2006, for the first time in American history, a Buddhist ordination was held where an American woman (Sister Khanti-Khema) took the Samaneri (novice) vows with an American monk (Bhante Vimalaramsi) presiding. This was done for the Buddhist American Forest Tradition at the Dhamma Sukha Meditation Center in Missouri.[54] In 2010 the first Tibetan Buddhist nunnery in America (Vajra Dakini Nunnery in Vermont) was officially consecrated. It offers novice ordination and follows the Drikung Kagyu lineage of Buddhism. The abbot of the Vajra Dakini nunnery is Khenmo Drolma, an American woman, who is the first bhikkhuni in the Drikung Kagyu lineage of Buddhism, having been ordained in Taiwan in 2002.[55][56] She is also the first westerner, male or female, to be installed as an abbot in the Drikung Kagyu lineage of Buddhism, having been installed as the abbot of the Vajra Dakini Nunnery in 2004.[55] The Vajra Dakini Nunnery does not follow The Eight Garudhammas.[57] Also in 2010, in Northern California, 4 novice nuns were given the full bhikkhuni ordination in the Thai Theravada tradition, which included the double ordination ceremony. Bhante Gunaratana and other monks and nuns were in attendance. It was the first such ordination ever in the Western hemisphere.[58] The following month, more bhikkhuni ordinations were completed in Southern California, led by Walpola Piyananda and other monks and nuns. The bhikkhunis ordained in Southern California were Lakshapathiye Samadhi (born in Sri Lanka), Cariyapanna, Susila, Sammasati (all three born in Vietnam), and Uttamanyana (born in Myanmar).[59]

Christianity

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity and gender |

|---|

|

In the liturgical traditions of Christianity, including the Roman Catholic Church, Eastern and Oriental Orthodoxy, Lutheranism and Anglicanism, the term ordination refers more narrowly to the means by which a person is included in one of the orders of bishops, priests or deacons. This is distinguished from the process of consecration to religious orders, namely nuns and monks, which are open to women and men. Some Protestant denominations understand ordination more generally as the acceptance of a person for pastoral work.

Supporters of the admission of women to Christian priesthood have argued the existence of documented instances of ordained women in the Early Church, as deacons, priests or bishops.[60] In AD 494 Pope Gelasius I wrote a letter condemning female participation in the celebration of the Eucharist, a role he felt was reserved for men.[61]

The ordination of women has once again been a controversial issue in more recent years; while many Christian denominations have responded positively to modern views of gender equality, some traditionalists take a more conservative view and oppose the admission of women into the priesthood. For example, some Anglo-Catholics or Evangelicals, while theologically very different, may share opposition to female ordination.[62] Evangelical Christians who place emphasis on the infallibility of the Bible base their opposition to women's ordination partly upon the writings of the Apostle Paul, such as Ephesians 5:23, 1 Timothy 2:11–15, which appears to demand male leadership in the Church.[63] Traditionalist Roman and Orthodox Catholics may allude to Jesus Christ's choice of disciples as evidence of his intention for an exclusively male Apostolic Succession, as laid down by early Christian writers such as Tertullian and reiterated in the 1976 Vatican Declaration on the Question of the Admission of Women to the Ministerial Priesthood.[64]

Supporters of women's ordination may point to the role of notable female figures in the Bible such as Phoebe and others in Romans 16:1, the female disciples of Jesus, and the women at the crucifixion who were the first witnesses to the Resurrection of Christ, as supporting evidence of the importance of women as leaders in the Early Church. They may also rely on exegetical interpretations of scriptural language related to gender.[63][65][66]

Anglican

In 1917 the Church of England licensed women as lay readers called bishop's messengers, many of whom ran churches, but did not go as far as to ordain them.

Within Anglicanism the majority of provinces ordain women as deacons and priests.[68]

The first three women priests ordained in the Anglican Communion were in the Anglican Diocese of Hong Kong and Macao: Li Tim-Oi in 1944 and Jane Hwang and Joyce Bennett in 1971.

On July 29, 1974, Bishops Daniel Corrigan, Robert L. DeWitt, and Edward R. Welles of the Episcopal Church of the U.S. ordained eleven women as priests in a ceremony that some considered "irregular" because the women lacked "recommendation from the standing committee," a canonical prerequisite for ordination. Initially opposed by the House of Bishops, the ordinations received approval from the General Convention of the Episcopal Church in September 1976. This General Convention approved the ordination of women to both the priesthood and the episcopate. The "Philadelphia Eleven" were Merrill Bittner, Alison Cheek, Alla Bozarth (Campell), Emily C. Hewitt, Carter Heyward, Suzanne R. Hiatt (d. 2002), Marie Moorefield, Jeannette Piccard (d. 1981), Betty Bone Schiess, Katrina Welles Swanson (d. 2006), and Nancy Hatch Wittig.[69]

A number of Anglican provinces also ordain women as bishops,[68][70] though, as of 2013, only six of the provinces have done so: the Episcopal Church in the United States, the Church of Ireland, and the Anglican churches of Aotearoa New Zealand and Polynesia, Australia, Canada and the Church of Southern Africa.[71] Cuba, one of the extra-provincial Anglican churches, has done so as well.

- In 1989, Barbara Harris was the first woman ordained as a bishop in the Anglican Communion, for the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts.

- In 1990, Penny Jamieson was ordained a bishop in New Zealand for the Diocese of Dunedin.

- In 1993, Victoria Matthews was elected a suffragan bishop in the Diocese of Toronto, Canada on November 19. She was consecrated in February 1994.[72]

- In 2007, Nerva Cot Aguilera was ordained a bishop in the Episcopal Church of Cuba.

- In 2008, Kay Goldsworthy was ordained as an assistant bishop for the Diocese of Perth.[73]

- In 2012, Ellinah Wamukoya was elected bishop of the Diocese of Swaziland in the Anglican Church of Southern Africa.[74] She was consecrated in November 2012.[75]

- In 2013, the Church of Ireland appointed Pat Storey as the first female bishop in Ireland and the UK.[76] The Church of Ireland has permitted the ordination of women as bishops since 1990.[77]

- In 2013, the Church of South India (CSI) appointed Rev. E. Pushpa Lalitha as the first female bishop in India.[78] She was appointed to the Nandyal Diocese of the Church.[79]

The Scottish Episcopal Church has permitted the ordination of women as bishops since 2003, but none have yet been consecrated.[80]

The Church of England authorised the ordination of woman priests in 1992 and began ordaining them in 1994, but the issue of women being ordained as bishops is contentious and has not been authorised. In 2010, a survey examining the rates of female priests being ordained in the Church of England showed that for the first time more women were ordained than men.[81] A high-profile vote at the 2012 General Synod failed to approve the ordination of women as bishops. The measure was lost after failing to achieve the two-thirds majority required in the House of Laity but being passed by the House of Bishops and the House of Clergy.[82] On June 18, 2006, the Episcopal Church in the United States was the first Anglican province to elect a woman, Katharine Jefferts Schori, as their Primate (the highest position possible in an Anglican province), called the "Presiding Bishop" in the United States.[71] With the October 16, 2010, ordination of Margaret Lee, in the Peoria-based Diocese of Quincy, Illinois, women have been ordained as priests in all 110 dioceses of the Episcopal Church in the United States.[83]

On September 12, 2013, the Governing Body of the Church in Wales passed a bill to enable women to be ordained as bishops, although none will be ordained for at least a year.[84] The issue was previously voted down in 2008.[85]

Jehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses consider qualified public baptism to represent the baptizand's ordination, following which he or she is immediately considered an ordained minister. In 1941, the Supreme Court of Vermont recognized the validity of this ordination for a female Jehovah's Witness minister.[86] The majority of Witnesses actively preaching from door to door are female.[87][needs update] Women are commonly appointed as full-time ministers, either to evangelize as "pioneers" or missionaries, or to serve at their branch offices.[88]

Nevertheless, Witness deacons ("ministerial servants") and elders must be male, and only a baptized adult male may perform a Jehovah's Witness baptism, funeral, or wedding.[89] Within the congregation, a female Witness minister may only lead prayer and teaching when there is a special need, and must do so wearing a head covering.[90][91][92]

Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints does not ordain women.[93] Some (most notably former LDS members D. Michael Quinn and Margaret Toscano) have argued that the church ordained women in the past and that therefore the church currently has the power to ordain women and should do so;[94][95] however, there are no known records of any women having been ordained to the priesthood.[96] Women do hold a prominent place in the church, including their work in the Relief Society which is one of the largest and most long-lasting women's organizations in the world.[97] Women thus serve, as do men, in unpaid positions involving teaching, administration, missionary service, humanitarian efforts, and other capacities.[98] Women often offer prayers and deliver sermons during Sunday services. Ordain Women is an organization of Mormon women who support extending priesthood ordinations to women.

Community of Christ

The Community of Christ adopted the practice of women's ordination in 1984,[99] which was one of the reasons for the schism between the Community of Christ and the newly formed Restoration Branches movement, which was largely composed of members of the Community of Christ church (then known as the RLDS church) who refused to accept this development and other doctrinal changes taking place during this same period. For example, the Community of Christ also changed the name of one of its priesthood offices from evangelist-patriarch to evangelist, and its associated sacrament, the patriarchal blessing, to the evangelist's blessing. In 2007, Becky L. Savage became the first female member of the Community of Christ's First Presidency.

Liberal Catholic

Of all the churches in the Liberal Catholic movement, only the original church, the Liberal Catholic Church under Bishop Graham Wale, does not ordain women. The position held by the Liberal Catholic Church is that the Church, even if it wanted to ordain women, does not have the authority to do so and that it is not possible for a woman to become a priest even if she went through the ordination ceremony. The reasoning behind this belief is that the female body does not effectively channel the masculine energies of Christ, the true minister of all the sacraments. The priest has to be able to channel Christ's energies to validly confect the sacrament; therefore priests must be male. When discussing the sacrament of Holy Orders in his book Science of the Sacraments, Second Presiding Bishop Leadbeater confirmed that women could not be ordained; he noted that Christ left no indication that women can become priests and that only Christ can change this arrangement.

Orthodox

The Orthodox Churches follow a line of reasoning similar to that of the Roman Catholic Church with respect to the ordination of priests and do not allow women's ordination.[100]

Evangelos Theodorou argued that female deacons were actually ordained in antiquity.[101] K. K. Fitzgerald has followed and amplified Theodorou's research. Bishop Kallistos Ware wrote:[102][verification needed]

The order of deaconesses seems definitely to have been considered an "ordained" ministry during early centuries in at any rate the Christian East. ... Some Orthodox writers regard deaconesses as having been a "lay" ministry. There are strong reasons for rejecting this view. In the Byzantine rite the liturgical office for the laying-on of hands for the deaconess is exactly parallel to that for the deacon; and so on the principle lex orandi, lex credendi—the Church's worshipping practice is a sure indication of its faith—it follows that the deaconesses receives, as does the deacon, a genuine sacramental ordination: not just a [χειροθεσια] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (chirothesia) but a [χειροτονια] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (chirotonia). However, the ordination of women in the Catholic Church does exist. Although it is not widespread, it is official by the Roman Catholic Church.

On October 8, 2004, the Holy Synod of the Orthodox Church of Greece voted to permit the appointment of monastic deaconesses, that is, women to minister and assist at the liturgy within their own monasteries, but it made clear that the rite was a χειροτονία (appointment), not a χειροθεσία (ordination).[103][104][105][106] There is a strong monastic tradition, pursued by both men and women in the Orthodox churches, where monks and nuns lead identical spiritual lives. Unlike Western-rite Catholic religious life, which has myriad traditions, both contemplative and active (see Benedictine monks, Franciscan friars, Jesuits), that of Orthodoxy has remained exclusively ascetic and monastic.

Seventh-day Adventists

Although the Seventh-day Adventist Church has no written policy forbidding the ordination of women, it has traditionally ordained only men. In recent years the ordination of women has been the subject of heated debate, especially in North America and Europe. In the Adventist church, candidates for ordination are chosen by local conferences (which usually administer about 50-150 local congregations) and approved by unions (which serve about 6-12 conferences). The world headquarters—the General Conference—says that the GC has the right to set the worldwide qualifications for ordination, including gender requirements. GC leaders have never taken the position that ordination of women is contrary to the Bible, but they have insisted that no one ordain women until it is acceptable to all parts of the world church.[107]

In 1990 the General Conference in world session voted not to establish a worldwide policy permitting the ordination of women, but they did not vote a policy forbidding such either.[108] In 1995 GC delegates voted not to authorize each of the 13 world divisions to establish ordination policies specific to its part of the world.[108] In 2011, the North American Division, without GC approval, voted to permit women to serve as conference presidents. In early 2012, the GC responded to the NAD action with an analysis of church history and policy, demonstrating that divisions do not have the authority to establish policy different from GC policy.[109] The NAD immediately rescinded their action. But in their analysis the GC reminded the world membership that the “final responsibility and authority” for deciding who is ordained resides at the union level. This led to decisions by several unions to approve ordinations without regard to gender.

On April 23, 2012, the North German Union voted to ordain women as ministers,[110] but by late 2013 had not yet ordained a woman. On July 29, 2012, the Columbia Union Conference voted to "authorize ordination without respect to gender."[111] On August 19, 2012 the Pacific Union Conference also voted to ordain without regard to gender.[112] Both unions began immediately approving ordinations of women.[113] By mid-2013, about 25 women had been ordained to the ministry in the Pacific Union Conference, plus several in the Columbia Union. On May 12, 2013, the Danish Union voted to treat men and women ministers the same, and to suspend all ordinations until after the topic is considered at the next GC session in 2015. On May 30, 2013 the Netherlands Union voted to ordain female pastors, recognizing them as equal to their male colleagues.[114] On Sept. 1, 2013, a woman was ordained in the Netherlands Union.[115]

In 2012-2013 the General Conference assembled several committees to study the issue and make a recommendation to be voted at the 2015 world General Conference session.[116]

On October 27th, 2013, Sandra Roberts became the first woman to lead a Seventh-day Adventist conference when she was elected as president of the Southeastern California Conference. [117] However, the worldwide Seventh-day Adventist church did not recognize this because presidents of conferences must be ordained pastors and the worldwide church did not recognize the ordination of women. [118]

As Protestant Christians who accept the Bible as their only rule of faith and practice, Seventh-day Adventists on both sides of the issue employ the same Bible texts and arguments used by other Protestants (e.g. 1 Tim. 2:12 and Gal. 3:28), but the fact that the most prominent and authoritative co-founder of the church—Ellen White—was a woman, also affects the discussion. Proponents of ordaining women point out that Adventists believe that Ellen White was chosen by God as a leader, preacher and teacher; that she remains the highest authority, outside the Bible, in the Seventh-day Adventist Church today; that she was regularly issued ordination credentials, which she carried without objection; and that she supported the ordination of women to at least some ministry roles. Opponents argue that because she was a prophet her example does not count, and that although she said she was ordained by God, she was never ordained in the ordinary way, by church leaders.[119]

Protestant

A key theological doctrine for Reformed and most other Protestants is the priesthood of all believers—a doctrine considered by them so important that it has been dubbed by some as "a clarion truth of Scripture".[120]

This doctrine restores true dignity and true integrity to all believers since it teaches that all believers are priests and that as priests, they are to serve God—no matter what legitimate vocation they pursue. Thus, there is no vocation that is more 'sacred' than any other. Because Christ is Lord over all areas of life, and because His word applies to all areas of life, nowhere does His Word even remotely suggest that the ministry is 'sacred' while all other vocations are 'secular.' Scripture knows no sacred-secular distinction. All of life belongs to God. All of life is sacred. All believers are priests."

— David Hagopian. Trading Places: The Priesthood of All Believers.[120]

Most Protestant denominations require pastors, ministers, deacons, and elders to be formally ordained.Eph. 4:11–13 While the process of ordination varies among the denominations and the specific church office to be held, it may require preparatory training such as seminary or Bible college, election by the congregation or appointment by a higher authority, and expectations of a lifestyle that requires a higher standard. For example, the Good News Translation of James 3:1 says, "My friends, not many of you should become teachers. As you know, we teachers will be judged with greater strictness than others."

Traditionally, these roles were male preserves, but over the last century an increasing number of denominations have begun ordaining women. The Church of England appointed female lay readers during the First World War. Later the United Church of Canada in 1936 and the American United Methodist Church in 1956 also began to ordain women.[121][122]

Meanwhile, women's ministry has been part of Methodist tradition in Britain for over 200 years. In the late 18th century in England, John Wesley allowed for female office-bearers and preachers.[123]

The Salvation Army has allowed the ordination of women since its beginning, although it was a hotly disputed topic between William and Catherine Booth.[124] The fourth, thirteenth, and nineteenth Generals of the Salvation Army were women.[125]

Today, over half of all American Protestant denominations ordain women,[126] but some restrict the official positions a woman can hold. For instance, some ordain women for the military or hospital chaplaincy but prohibit them from serving in congregational roles. Over one-third of all seminary students (and in some seminaries nearly half) are female.[127][128]

The Protestant denominations that refuse to ordain women often do so on the basis of New Testament scriptures that they interpret as prohibiting women from fulfilling church roles that require ordination[129] An especially important consideration here is the way 1 Timothy 2:12 is translated and interpreted in the New Testament.[129]

Roman Catholic

The teaching of the Roman Catholic Church, as emphasised by Pope John Paul II in the apostolic letter "Ordinatio sacerdotalis", is "that the Church has no authority whatsoever to confer priestly ordination on women and that this judgment is to be definitively held by all the Church's faithful."[130] This teaching is embodied in the current canon law (specifically canon law 1024[131]) and the Catechism of the Catholic Church, by the canonical statement: "Only a baptized man (in Latin, vir) validly receives sacred ordination."[132] Insofar as priestly and episcopal ordination are concerned, the Roman Catholic Church teaches that this requirement is a matter of divine law; it belongs to the deposit of faith and is unchangeable.[133][134][135] In 2007, the Holy See issued a decree saying that the attempted ordination of women would result in automatic excommunication for the women and priests trying to ordain them.[136] In 2010, the Holy See stated that the ordination of women is a "grave delict".[137]

Ludmila Javorová

Ludmila Javorová claims to have been secretly ordained as a Catholic priest in Czechoslovakia during 1970 by a friend of her family, Bishop Felix Davídek (1921–88), himself clandestinely consecrated, due to the shortage of priests caused by communist persecution. Her claim was made after Davídek’s death and she is not recognized as ordained by the Catholic Church.[138]

Dissent

Some dissenting scholars (for example, Father Robert W. Hovda, Robert J. Karris and Damien Casey) have written in favor of ordaining women.[139] Furthermore, 12 groups have been founded throughout the world advocating for women's ordination in the Catholic Church.[140] Women's Ordination Worldwide, founded in 1996 in Austria, is a network of national and international groups whose primary mission is the admission of Roman Catholic women to all ordained ministries, including Catholic Women's Ordination (founded in March 1993 in the United Kingdom[141]), Roman Catholic Womenpriests (founded in 2002 in America[142]), Women's Ordination Conference (founded in 1975 in America[143]) and others. The first recorded Catholic organization advocating for women's ordination was St. Joan's Alliance, founded in 1911 in London. [144]

Islam

Although Muslims do not formally ordain religious leaders, the imam serves as a spiritual leader and religious authority. There is a current controversy among Muslims on the circumstances in which women may act as imams—that is, lead a congregation in salat (prayer). Three of the four Sunni schools, as well as many Shia, agree that a woman may lead a congregation consisting of women alone in prayer, although the Maliki school does not allow this. According to all currently existing traditional schools of Islam, a woman cannot lead a mixed gender congregation in salat (prayer). Some schools make exceptions for Tarawih (optional Ramadan prayers) or for a congregation consisting only of close relatives. Certain medieval scholars—including Al-Tabari (838–932), Abu Thawr (764–854), Al-Muzani (791–878), and Ibn Arabi (1165–1240)—considered the practice permissible at least for optional (nafila) prayers; however, their views are not accepted by any major surviving group. Islamic feminists have begun to protest this.

Women's mosques, called nusi, and female imams have existed since the 19th century in China and continue today.[145]

In 1994, Amina Wadud, (an Islamic studies professor at Virginia Commonwealth University, born in the United States), became the first woman in South Africa to deliver the jum'ah khutbah (Friday sermon), which she did at the Claremont Main Road Mosque in Cape Town, South Africa.[146]

In 2004 20-year-old Maryam Mirza delivered the second half of the Eid al-Fitr khutbah at the Etobicoke mosque in Toronto, Canada, run by the United Muslim Association.[147]

In 2004, in Canada, Yasmin Shadeer led the night 'Isha prayer for a mixed-gender (men as well as women praying and hearing the sermon) congregation.[148] This is the first recorded occasion in modern times where a woman led a congregation in prayer in a mosque.[148]

On March 18, 2005, Amina Wadud gave a sermon and led Friday prayers for a Muslim congregation consisting of men as well as women, with no curtain dividing the men and women.[149] Another woman, Suheyla El-Attar, sounded the call to prayer while not wearing a headscarf at that same event.[149] This was done in the Synod House of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York after mosques refused to host the event.[149] This was the first known time that a woman had led a mixed-gender Muslim congregation in prayer in American history.[149]

In April 2005, Raheel Raza, born in Pakistan, led Toronto's first woman-led mixed-gender Friday prayer service, delivering the sermon and leading the prayers of the mixed-gender congregation organized by the Muslim Canadian Congress to celebrate Earth Day in the backyard of the downtown Toronto home of activist Tarek Fatah.[150]

On July 1, 2005, Pamela Taylor, a Muslim convert since 1986, became the first woman to lead Friday prayers in a Canadian mosque, and did so for a congregation of both men and women.[151] Pamela Taylor is an American convert to Islam and co-chair of the New York-based Progressive Muslim Union.[151] In addition to leading the prayers, Taylor also gave a sermon on the importance of equality among people regardless of gender, race, sexual orientation and disability.[151]

In October 2005, Amina Wadud led a mixed gender Muslim congregational prayer in Barcelona.[152]

In 2008, Pamela Taylor gave the Friday khutbah and led the mixed-gender prayers in Toronto at the UMA mosque at the invitation of the Muslim Canadian Congress on Canada Day.[153]

On 17 October 2008, Amina Wadud became the first woman to lead a mixed-gender Muslim congregation in prayer in the United Kingdom when she performed the Friday prayers at Oxford's Wolfson College.[154]

In 2010, Raheel Raza became the first Muslim-born woman to lead a mixed-gender British congregation through Friday prayers.[155]

Judaism

Only men can become rabbis in Orthodox Judaism (although there has been one female Hasidic rebbe, Hannah Rachel Verbermacher, also known as the Maiden of Ludmir, active in the 19th century[157]); however all other types of Judaism allow and have female rabbis.[158] In 1935 Regina Jonas was ordained privately by a German rabbi and became the world's first female rabbi.[156] Sally Priesand became the first female rabbi in Reform Judaism in 1972,[159] Sandy Eisenberg Sasso became the first female rabbi in Reconstructionist Judaism in 1974,[160] Lynn Gottlieb became the first female rabbi in Jewish Renewal in 1981,[161] Amy Eilberg became the first female rabbi in Conservative Judaism in 1985,[162] and Tamara Kolton became the very first rabbi of either sex (and therefore, since she was female, the first female rabbi) in Humanistic Judaism in 1999.[163] Women in these types of Judaism are routinely granted semicha (meaning ordination) on an equal basis with men.

Only men can become cantors (also called hazzans) in Orthodox Judaism, but all other types of Judaism allow and have female cantors.[164] In 1955 Betty Robbins, born in Greece, became the world's first female cantor when she was appointed cantor of the Reform congregation of Temple Avodah in Oceanside, New York, in July.[165] Barbara Ostfeld-Horowitz became the first female cantor to be ordained in Reform Judaism in 1975.[166] Erica Lippitz and Marla Rosenfeld Barugel became the first female cantors in Conservative Judaism in 1987.[166] However, the Cantors Assembly, a professional organization of cantors associated with Conservative Judaism, did not allow women to join until 1990.[167] In 2001 Deborah Davis became the first cantor of either sex (and therefore, since she was female, the first female cantor) in Humanistic Judaism, although Humanistic Judaism has since stopped graduating cantors.[168] Sharon Hordes became the first cantor of either sex (and therefore, since she was female, the first female cantor) in Reconstructionist Judaism in 2002.[169] Avitall Gerstetter, who lives in Germany, became the first female cantor in Jewish Renewal (and the first female cantor in Germany) in 2002. Susan Wehle became the first American female cantor in Jewish Renewal in 2006; however, she died in 2009.[170] The first American women to be ordained as cantors in Jewish Renewal after Susan Wehle's ordination were Michal Rubin and Abbe Lyons, both ordained on January 10, 2010.[171]

Ryukyuan religion

The indigenous religion of the Ryukyuan Islands in Japan is led by female priests; this makes it the only known official mainstream religion of a society led by women.[172]

Shinto

In Shintoism, Saiin (斎院, saiin?) were unmarried female relatives of the Japanese emperor who served as high priestesses at Ise Grand Shrine from the late 7th century until the 14th century. Ise Grand Shrine is a Shinto shrine dedicated to the goddess Amaterasu-ōmikami. Saiin priestesses were usually elected from royalty (内親王, naishinnō) such as princesses (女王, joō). In principle, Saiin remained unmarried, but there were exceptions. Some Saiin became consorts of the Emperor, called Nyōgo in Japanese. According to the Man'yōshū (The Anthology of Ten Thousand Leaves), the first Saiō to serve at Ise Grand Shrine was Princess Oku, daughter of Emperor Temmu, during the Asuka period of Japanese history.

The ordination of women as Shinto priests arose again after the abolition of State Shinto in the aftermath of World War II.[173] See also Miko.

Sikhism

Sikhism does not have priests, which were abolished by Guru Gobind Singh, as the guru had seen that institution become corrupt in society during his time. Instead, he appointed the Guru Granth Sahib, the Sikh holy book, as his successor as Guru instead of a possibly fallible human. Due to the faith's belief in complete equality, women can participate in any religious function, perform any Sikh ceremony or lead the congregation in prayer.[174] A Sikh woman has the right to become a Granthi, Ragi, and one of the Panj Piare (5 beloved) and both men and women are considered capable of reaching the highest levels of spirituality.[175]

Taoism

Taoists ordain both men and women as priests.[176] In 2009 Wu Chengzhen became the first female fangzhang (principal abbot) in Taoism's 1,800-year history after being enthroned at Changchun Temple in Wuhan, capital of Hubei province, in China.[177] Fangzhang is the highest position in a Taoist temple.[177]

Wicca

There are many different Wiccan traditions. All ordain women as priests (most also ordain men), and some were created by women.[178][179][180]

Yoruba

The Yoruba people of western Nigeria practice an indigenous religion with a religious hierarchy of priests and priestesses that dates to 800-1000 CE. Ifá Oracle priests and priestesses bear the titles Babalawo and Iyanifa respectively.[181] Priests and priestesses of the varied Orisha, when not already bearing the higher ranked oracular titles mentioned above, are referred to as babalorisa when male and iyalorisa when female.[182] Initiates are also given an Orisa or Ifá name that signifies under which deity they are initiated; for example a priestess of Oshun may be named Osunyemi and a priest of Ifá may be named Ifáyemi.

Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrian priests in India are required to be male.[183] However, women have been ordained in Iran and North America as mobedyars, meaning women mobeds (Zoroastrian priests).[184][185][186] In 2011 the Tehran Mobeds Anjuman (Anjoman-e-Mobedan) announced that for the first time in the history of Iran and of the Zoroastrian communities worldwide, women had joined the group of mobeds (priests) in Iran as mobedyars (women priests); the women hold official certificates and can perform the lower-rung religious functions and can initiate people into the religion.[184]

Some significant dates and events

This section needs expansion with: decisions against women's ordination to balance the list. You can help by adding to it. (June 2008) |

A list with dates of important events in the history of women's ordination appears below:[187]

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity and gender |

|---|

|

- 6th century BCE Mahapajapati Gotami, the aunt and foster mother of Buddha, was the first woman to receive Buddhist ordination.[39][188]

- 5th century? Prajñādhara (Prajnatara), the twenty-seventh Indian Patriarch of Zen Buddhism and teacher of Bodhidharma, is believed to have been a woman.[40]

- 13th century The first female Zen master, as well as the first Zen abbess, was the Japanese abbess Mugai Nyodai (born 1223 - died 1298).[189][190]

- 17th century: Asenath Barzani led and taught at a yeshiva in Iraq.[191]

- Circa 1770: Mary Evans Thorne was appointed class leader by Joseph Pilmore in Philadelphia, probably the first woman in America to be so appointed.[192]

- Late 18th century: John Wesley allowed women to preach within his Methodist movement.[123]

- Early 19th century: A fundamental belief[193] of the Society of Friends (Quakers) has always been the existence of an element of God's spirit in every human soul.[187] Thus all persons are considered to have inherent and equal worth, independent of their gender, and this led to an acceptance of female ministers.[187] In 1660, Margaret Fell (1614–1702) published a famous pamphlet to justify equal roles for men and women in the denomination, titled: "Women's Speaking Justified, Proved and Allowed of by the Scriptures, All Such as Speak by the Spirit and Power of the Lord Jesus And How Women Were the First That Preached the Tidings of the Resurrection of Jesus, and Were Sent by Christ's Own Command Before He Ascended to the Father (John 20:17)."[187] In the United States, in contrast with almost every other organized denomination, the Society of Friends (Quakers) has allowed women to serve as ministers since the early 19th century.[187] Furthermore, in England in the 17th century Elizabeth Hooton became the first female Quaker minister.[194]

- 19th century: Women's mosques, called nusi, and female imams have existed since the 19th century in China and continue today.[145]

- 19th century: Hannah Rachel Verbermacher, also known as the Maiden of Ludmir (Ludmirer Moyd), became the only female Rebbe in the history of the Hasidic movement; she lived in Ukraine and Israel.[157]

- 1807: The Primitive Methodist Church in Britain first allowed female ministers.

- 1810: The Christian Connection Church, an early relative of the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) and the United Church of Christ, ordained women as early as 1810.

- 1815: Clarissa Danforth was ordained in New England. She was the first woman ordained by the Free Will Baptist denomination.

- 1815: The first petition for the African Methodist Episcopal Church General Conference to license women to preach is defeated.[195]

- 1853: Antoinette Brown Blackwell was the first woman ordained as a minister in the United States.[196] She was ordained by a church belonging to the Congregationalist Church.[197] However, her ordination was not recognized by the denomination.[187] She later quit the church and became a Unitarian.[187] The Congregationalists later merged with others to create the United Church of Christ, which ordains women.[187][198]

- 1861: Mary A. Will was the first woman ordained in the Wesleyan Methodist Connection by the Illinois Conference in the United States. The Wesleyan Methodist Connection eventually became the Wesleyan Church.

- 1863: Olympia Brown was ordained by the Universalist denomination in 1863, the first woman ordained by that denomination, in spite of a last-moment case of cold feet by her seminary which feared adverse publicity.[199] After a decade and a half of service as a full-time minister, she became a part-time minister in order to devote more time to the fight for women's rights and universal suffrage.[187] In 1961, the Universalists and Unitarians joined to form the Unitarian Universalist Association (UUA).[200] The UUA became the first large denomination to have a majority of female ministers.[187]

- 1865: The Salvation Army was founded, which in the English Methodist tradition always ordained both men and women.[187] However, there were initially rules that prohibited a woman from marrying a man who had a lower rank.[187]

- 1866: Helenor M. Davison was ordained as a deacon by the North Indiana Conference of the Methodist Protestant Church, probably making her the first ordained woman in the Methodist tradition.[192]

- 1869: Margaret Newton Van Cott became the first woman in the Methodist Episcopal Church to receive a local preacher's license.[192]

- 1869: Lydia Sexton (of the United Brethren Church) was appointed chaplain of the Kansas State Prison at the age of 70, the first woman in the United States to hold such a position.[192]

- 1871: Celia Burleigh became the first female Unitarian minister.[187]

- 1876: Anna Oliver was the first woman to receive a Bachelor of Divinity degree from an American seminary (Boston University School of Theology).[192]

- 1879: The Church of Christ, Scientist was founded by a woman, Mary Baker Eddy.[201]

- 1880: Anna Howard Shaw was the first woman ordained in the Methodist Protestant Church, an American church which later merged with other denominations to form the United Methodist Church.[202]

- 1886: Louise “Lulu” Fleming becomes the first black woman to be commissioned for career missionary service by the Women’s Baptist Foreign Missionary Society of the West.[195]

- 1888: Sarah E. Gorham becomes the first woman missionary of the African Methodist Episcopal Church appointed to a foreign field.[195]

- 1888: Fidelia Gillette may have been the first ordained woman in Canada.[187] She served the Universalist congregation in Bloomfield, Ontario, during 1888 and 1889.[187] She was presumably ordained in 1888 or earlier.[187][original research?]

- 1889: The Nolin Presbytery of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church ordained Louisa Woosley as the first female minister of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church, USA.[203]

- 1889: Ella Niswonger was the first woman ordained in the American United Brethren Church, which later merged with other denominations to form the American United Methodist Church, which has ordained women with full clergy rights and conference membership since 1956.[192][204]

- 1890: On September 14, 1890, Ray Frank gave the Rosh Hashana sermon for a community in Spokane, Washington, thus becoming the first woman to preach from a synagogue pulpit, although she was not a rabbi.[205]

- 1892: Anna Hanscombe is believed to be the first woman ordained by the parent bodies which formed the Church of the Nazarene in 1919.[187]

- 1894: Julia A. J. Foote was the first woman to be ordained as a deacon by the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church.[192]

- 1909: The Church of God (Cleveland, Tennessee) began ordaining women in 1909.[187]

- 1911: Ann Allebach was the first Mennonite woman to be ordained.[187] This occurred at the First Mennonite Church of Philadelphia.[187]

- 1912: Olive Winchester, born in America, became the first woman ordained by any trinitarian Christian denomination in the United Kingdom when she was ordained by the Church of the Nazarene.[206][207]

- 1914: The Assemblies of God was founded and ordained its first woman pastors in 1914.[187]

- 1917: The Church of England appointed female "bishop's messengers" to preach, teach, and take missions in the absence of men.

- 1917: The Congregationalist Church (England and Wales) ordained their first woman, Constance Coltman (née Todd), at the King's Weigh House, London.[208] Its successor is the United Reformed Church[187][209] (a union of the Congregational Church in England and Wales and the Presbyterian Church of England in 1972). Since then two more denominations have joined the union: The Reformed Churches of Christ (1982) and the Congregational Church of Scotland (2000). All of these denominations ordained women at the time of Union and continue to do so. The first woman to be appointed General Secretary of the United Reformed Church was Roberta Rominger in 2008.

- 1920: The Methodist Episcopal Church granted women the right to become licensed as local preachers.[192]

- 1920s: Some Baptist denominations started ordaining women.[187]

- 1922: The Jewish Reform movement's Central Conference of American Rabbis stated that "...woman cannot justly be denied the privilege of ordination."[210] However, the first woman in Reform Judaism to be ordained (Sally Priesand) was not ordained until 1972.[159]

- 1922: The Annual Conference of the Church of the Brethren granted women the right to be licensed into the ministry, but not to be ordained with the same status as men.[187]

- 1924: The Methodist Episcopal Church granted women limited clergy rights as local elders or deacons, without conference membership.[192]

- 1924: Ida B. Robinson founded the Mount Sinai Holy Church of America and became the organization's first presiding bishop and president.

- 1929: Izabela Wiłucka-Kowalska was the first woman to be ordained by the Old Catholic Mariavite Church in Poland.

- 1930: A predecessor church of the Presbyterian Church (USA) ordained its first female as an elder.[187]

- 1935: Regina Jonas was ordained privately by a German rabbi and became the world's first female rabbi.[156]

- 1935: Women were commissioned as deacons in the Church of Scotland from 1935.

- 1936: Lydia Emelie Gruchy became the first female minister in the United Church of Canada. In 1953, the Reverend Lydia Emelie Grouchy was the first Canadian woman to receive an honorary Doctor of Divinity.[211]

- 1938: Tehilla Lichtenstein became the first Jewish American woman to serve as the spiritual leader of an ongoing Jewish congregation, although she was not ordained.[212]

- 1944: Florence Li Tim Oi became the first woman to be ordained as an Anglican priest. She was born in Hong Kong, and was ordained in Guandong province in unoccupied China on January 25, 1944, on account of a severe shortage of priests due to World War II. When the war ended, she was forced to relinquish her priesthood, yet she was reinstated as a priest later in 1971 in Hong Kong. "When Hong Kong ordained two further women priests in 1971 (Joyce Bennett and Jane Hwang), Florence Li Tim-Oi was officially recognised as a priest by the diocese."[213] She later moved to Toronto, Canada, and assisted as a priest there from 1983 onwards.

- 1947: The Lutheran Protestant Church started to ordain women as priests.[214]

- 1947: The Czechoslovak Hussite Church started to ordain women.[187]

- 1948: The Evangelical Lutheran Church of Denmark started to ordain women.[187]

- 1949: The Old Catholic Church (in the U.S.) started to ordain women.[187]

- 1949: Women were allowed to preach in the Church of Scotland from 1949.

- 1949: Eleanora Figaro became the first black woman to receive the papal honor Pro Ecclesia et Pontifice.[195]

- 1951: From January 1951 until 1953, Paula Ackerman served as Temple Beth Israel’s spiritual leader, conducting services, preaching, teaching, and performing marriages, funerals, and conversions. In so doing, she achieved the distinction of becoming the first woman to assume religious leadership of a mainstream American Jewish congregation, although she was never ordained.

- 1952: Queen Elizabeth II becomes Supreme Governor of the Church of England.[215][216]

- 1955: In 1955 Betty Robbins, born in Greece, became the world's first female cantor when she was appointed cantor of the Reform congregation of Temple Avodah in Oceanside, New York, in July.[165]

- 1956: Maud K. Jensen was the first woman to receive full clergy rights and conference membership (in her case, in the Central Pennsylvania Conference) in the Methodist Church.[122]

- 1956: The Presbyterian Church (USA) ordained its first female minister, Margaret Towner.[217]

- 1957: In 1957 the Unity Synod of the Moravian Church declared of women's ordination "in principle such ordination is permissible" and that each province is at liberty to "take such steps as seem essential for the maintenance of the ministry of the Word and Sacraments;” however, while this was approved by the Unity Synod in 1957, the Northern Province of the Moravian Church did not approve women for ordination until 1970 at the Provincial Synod, and it was not until 1975 that the Revd Mary Matz became the first female minister within the Moravian Church.[218]

- 1958: Women ministers in the Church of the Brethren were given full ordination with the same status as men.[219]

- 1958: The Church of Sweden became the first Lutheran church to ordain female pastors in 1958.

- 1959: The Reverend Gusta A. Robinette, a missionary, was ordained in the Sumatra (Indonesia) Conference soon after The Methodist Church granted full clergy rights to women in 1956. She was appointed District Superintendent of the Medan Chinese District in Indonesia becoming the first female district superintendent in the Methodist Church.[192]

- 1960: The Evangelical Lutheran Church of Sweden started ordaining women.[187]

- 1964: Addie Davis became the first Southern Baptist woman to be ordained.[220] However, the Southern Baptist Convention stopped ordaining women in 2000, although existing female pastors are allowed to continue their jobs.[187]

- 1965: Rachel Henderlite became the first woman ordained in the Presbyterian Church in the United States; she was ordained by the Hanover Presbytery in Virginia.[221][222]

- 1966: Woman elders were introduced in 1966 in the Church of Scotland.

- 1967: The Presbyterian Church in Canada started ordaining women.[219]

- 1967: Margaret Henrichsen became the first American female district superintendent in the Methodist Church.[192]

- 1968: Women ministers were introduced in the Church of Scotland in 1968.

- 1970: The Northern Province of the Moravian Church approved women for ordination in 1970 at the Provincial Synod, but it was not until 1975 that the Revd Mary Matz became the first female minister within the Moravian Church.[218]

- 1970: In 1970 Ludmila Javorova attempted ordination as a Catholic priest in Czechoslovakia by a friend of her family, Bishop Felix Davidek (1921–88), himself clandestinely consecrated, due to the shortage of priests caused by communist persecution; however, an official Vatican statement in February 2000 declared the ordinations invalid while recognizing the severe circumstances under which they occurred.[138]

- 1970: On November 22, 1970, Elizabeth Alvina Platz became the first woman ordained by the Lutheran Church in America, and as such was the first woman ordained by any Lutheran denomination in America.[223] The first woman ordained by the American Lutheran Church, Barbara Andrews, was ordained in December 1970.[224] On January 1, 1988 the Lutheran Church in America, the American Lutheran Church, and the Association of Evangelical Lutheran Churches merged to form the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, which continues to ordain women.[225] (The first woman ordained by the Association of Evangelical Lutheran Churches, Janith Otte, was ordained in 1977.[226])

- 1971: Joyce Bennett and Jane Hwang were the first regularly ordained priests in the Anglican Church in Hong Kong.[187]

- 1972: Freda Smith became the first female minister to be ordained by the Metropolitan Community Church.[227]

- 1972: Sally Priesand became the first female rabbi to be ordained in Reform Judaism, and also the first female rabbi in the world to be ordained by any theological seminary.[159]

- 1973: Emma Sommers Richards became the first Mennonite woman to be ordained as a pastor of a Mennonite congregation (Lombard Mennonite Church in Illinois).[228]

- 1974: The Methodist Church in the United Kingdom started to ordain women again (after a lapse of ordinations).

- 1974: Sandy Eisenberg Sasso became the first female rabbi to be ordained in Reconstructionist Judaism.[229]

- 1974: The Philadelphia Eleven are ordained into the Priesthood of the Episcopal Church of the U.S.A.[230]

- 1975: The Evangelical Lutheran Church of Latvia decided to ordain women as pastors, although since 1993, under the leadership of Archbishop Janis Vanags, it no longer does so.

- 1975: Dorothea W. Harvey became the first woman to be ordained by the Swedenborgian Church.[231]

- 1975: Barbara Ostfeld-Horowitz became the first female cantor in Reform Judaism.[166]

- 1975: In 1975, the Revd Mary Matz became the first female minister in the Moravian Church.[218]

- 1975: Jackie Tabick, born in Dublin, became the first female rabbi ordained in England.[232]

- 1976: Michal Mendelsohn (born Michal Bernstein) became the first presiding female rabbi in a North American congregation when she was hired by Temple Beth El Shalom in San Jose, California, in 1976.[233][234]

- 1976: The Anglican Church in Canada ordained six female priests.[72]

- 1976: The Revd Pamela McGee was the first female ordained to the Lutheran ministry in Canada.[187]

- 1976: Venerable Karuna Dharma became the first fully ordained female member of the Buddhist monastic community in the U.S.[235]

- 1977: The Anglican Church in New Zealand ordained five female priests.[187]

- 1977: Pauli Murray became the first African American woman to be ordained as an Episcopal priest in 1977.[236]

- 1977: The first woman ordained by the Association of Evangelical Lutheran Churches, Janith Otte, was ordained in 1977.[226]

- 1977: On January 1, 1977, Jacqueline Means became the first woman ordained to the priesthood in the Episcopal Church.[237] 11 women were "irregularly" ordained to the priesthood in Philadelphia on July 29, 1974, before church laws were changed to permit women's ordination.[230] They are often called the "Philadelphia 11". Church laws were changed on September 16, 1976.[230]

- 1978: Bonnie Koppell became the first female rabbi to serve in the U.S. military.[238]

- 1978: Linda Rich became the first female cantor to sing in a Conservative synagogue, specifically Temple Beth Zion in Los Angeles, although she was not ordained.[239]

- 1978: Mindy Jacobsen became the first blind woman to be ordained as a cantor in the history of Judaism.[240]

- 1979: The Reformed Church in America started ordaining women as ministers.[241] Women had been admitted to the offices of deacon and elder in 1972.[187]

- 1979: Linda Joy Holtzman became one of the first women in the United States to serve as the presiding rabbi of a synagogue, when she was hired by Beth Israel Congregation of Chester County, which was then located in Coatesville, Pennsylvania.[242] She had graduated in 1979 from the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College in Philadelphia, yet was hired by Beth Israel despite their being a Conservative congregation.[243] She was thus the first woman to serve as a rabbi for a Conservative congregation, as the Conservative movement did not then ordain women.[244]

- 1980: Marjorie Matthews, at the age of 64, was the first woman elected as a bishop in the United Methodist Church.[245][246]

- 1981: Lynn Gottlieb became the first female rabbi to be ordained in the Jewish Renewal movement.[161]

- 1981: Kinneret Shiryon, born in the United States, became the first female rabbi in Israel.[247][248]

- 1981: Ani Pema Chodron is an American woman who was ordained as a bhikkhuni (a fully ordained Buddhist nun) in a lineage of Tibetan Buddhism in 1981. Pema Chödrön was the first American woman to be ordained as a Buddhist nun in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition.[33][34]

- 1981: Karen Soria, born and ordained in the United States, became Australia's first female rabbi.[249][250]

- 1982: Nyambura J. Njoroge became the first female ordained minister in the Presbyterian Church of East Africa.[251]

- 1983: An Anglican woman was ordained in Kenya.[187]

- 1983: Three Anglican women were ordained in Uganda.[187]

- 1983: Elyse Goldstein, born in the United States and ordained in 1983, became the first female rabbi in Canada.[252][253][254]

- 1984: The Community of Christ (known at the time as the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints) authorized the ordination of women.[187] They are the second largest Latter Day Saint denomination.[187] A schism brought on by this change and others led to the formation of the Restoration Branches movement, the Restoration Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints and the Remnant Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints all of which reject female priesthood, although not always the ordination of women in all contexts.

- 1984: Leontine Kelly, the first black woman bishop of a major religious denomination in the United States, is elected head of the United Methodist Church in the San Francisco area.[195]

- 1984: Dr. Deborah Cohen became the first certified Reform mohelet (female mohel); she was certified by the Berit Mila program of Reform Judaism.[255]

- 1985: According to the New York Times for 1985-FEB-14: "After years of debate, the worldwide governing body of Conservative Judaism has decided to admit women as rabbis. The group, the Rabbinical Assembly, plans to announce its decision at a news conference...at the Jewish Theological Seminary...".[187] In 1985 Amy Eilberg became the first female rabbi to be ordained in Conservative Judaism.[256]

- 1985: The first women deacons were ordained by the Scottish Episcopal Church.[187]

- 1985: Judy Harrow became the first member of CoG (Covenant of the Goddess, a Wiccan group) to be legally registered as clergy in New York City in 1985, after a five-year effort requiring the assistance of the New York Civil Liberties Union.[257]

- 1986: Rabbi Julie Schwartz became the first female Naval chaplain in the U.S.[258]

- 1987: Erica Lippitz and Marla Rosenfeld Barugel became the first female cantors in Conservative Judaism.[166]

- 1987: Joy Levitt became the first female president of the Reconstructionist Rabbinical Association.[259]

- 1988: The Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland started to ordain women.[187]

- 1988: Virginia Nagel was ordained as the first Deaf female priest in the Episcopal Church.[260]

- 1988: Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo, an American woman formerly called Catharine Burroughs, became the first Western woman to be named a reincarnate lama.[261]

- 1988: The Episcopal Church elected Barbara Harris as its first female bishop.[262]

- 1989: Einat Ramon, ordained in New York, became the first female native-Israeli rabbi.[263]

- 1990: Pauline Bebe became the first female rabbi in France, although she was ordained in England.[264][265]

- 1990: Penny Jamieson became the first female Anglican diocesan bishop in the world. She was ordained a bishop of the Anglican Church in New Zealand in June 1990.[266]

- 1990: Anglican women were ordained in Ireland.[187]

- 1990: Sister Cora Billings was installed as a pastor in Richmond, VA, becoming the first black nun to head a parish in the U.S.[195]

- 1991: The Presbyterian Church of Australia ceased ordaining women to the ministry in 1991, but the rights of women ordained prior to this time were not affected.

- 1992: Naamah Kelman, born in the United States, became the first female rabbi ordained in Israel.[267][268]

- 1992: In March 1992 the first female priests in Australia were appointed; they were priests of the Anglican Church in Australia.[269]

- 1992: Maria Jepsen became the world's first woman to be elected a Lutheran bishop when she was elected bishop of the North Elbian Evangelical Lutheran Church in Germany, but she resigned in 2010 after allegations that she failed to properly investigate cases of sexual abuse.[270]

- 1992: In November 1992 the General Synod of the Church of England approved the ordination of women as priests.[271]

- 1992: The Anglican Church of South Africa started to ordain women.[187]

- 1992: Rabbi Karen Soria became the first female rabbi to serve in the U.S. Marines, which she did from 1992 until 1996.[272]

- 1993: Rebecca Dubowe became the first Deaf woman to be ordained as a rabbi in the United States.[273]

- 1993: The Communauté Evangélique Mennonite au Congo (Mennonite Evangelical Community of Congo) voted to ordain women as pastors.[274]

- 1993: Valerie Stessin became the first female Conservative rabbi to be ordained in Israel.[263]

- 1993: Chana Timoner became the first female rabbi to hold an active duty assignment as a chaplain in the U.S. Army.[275]

- 1993: Victoria Matthews was elected as the first female bishop of the Anglican Church of Canada; however she resigned in 2007, stating that “God is now calling me in a different direction”.[276] In 2008, she was ordained as Bishop of Christchurch, becoming the first woman to hold that position.[277]

- 1993: Rosemarie Kohn became the first female bishop to be appointed in the Church of Norway.[278][279]

- 1993: Leslie Friedlander became the first female cantor ordained by the Academy for Jewish Religion (New York).[280][281]

- 1993: Maya Leibovich became the first native-born female rabbi in Israel.[282]

- 1993: Ariel Stone, also called C. Ariel Stone, became the first American Reform rabbi to lead a congregation in the former Soviet Union, and the first liberal rabbi in Ukraine.[283][284][285] She worked as a rabbi in Ukraine from 1993 until 1994, leaving her former job at the Temple of Israel in Miami.[283][284][286]

- 1994:Lia Bass was ordained by the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, thus becoming the first Latin-American female rabbi in the world as well as the first woman from Brazil to be ordained as a rabbi.[287][288][289][290]

- 1994: The first women priests were ordained by the Scottish Episcopal Church.[187]

- 1994: Rabbi Laura Geller became the first woman to lead a major metropolitan congregation, specifically Temple Emanuel in Beverly Hills.[291][292]

- 1994: Indrani Rampersad was ordained as the first female Hindu priest in Trinidad.[293]

- 1994: On March 12, 1994, the Church of England ordained 32 women as its first female priests.[294]

- 1994: Amina Wadud, born in the United States, became the first woman in South Africa to deliver the jum'ah khutbah, at the Claremont Main Road Mosque in Cape Town.[146]

- 1995: The Sligo Seventh-day Adventist Church in Takoma Park, Maryland, ordained three women in violation of the denomination's rules - Kendra Haloviak, Norma Osborn, and Penny Shell.[295]

- 1995: The Evangelical Lutheran Church in Denmark ordained its first female bishop.[296]

- 1995: Bea Wyler, born in Switzerland, became the second female rabbi in Germany (the first being Regina Jonas),and the first to officiate at a congregation.[297][298]

- 1995: The Christian Reformed Church voted to allow women ministers, elders and evangelists.[187] In 1998, the North American Presbyterian and Reformed Council (NAPARC) suspended the CRC's membership because of this decision.[187]

- 1995: Lise-Lotte Rebel was elected as the first female bishop in the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Denmark.[299]

- 1995: In May 1995, Bola Odeleke was ordained as the first female bishop in Africa. Specifically, she was ordained in Nigeria.[300]

- 1996: Through the efforts of Sakyadhita, an International Buddhist Women Association, ten Sri Lankan women were ordained as bhikkhunis in Sarnath, India.[44]

- 1996: Subhana Barzagi Roshi became the Diamond Sangha's first female roshi (Zen teacher) when she received transmission on March 9, 1996, in Australia. In the ceremony Subhanna also became the first female roshi in the lineage of Robert Aitken Roshi.[301]

- 1997: Rosalina Rabaria became the first female priest in the Philippine Independent Church.[302]

- 1997: Christina Odenberg became the first female bishop in the Church of Sweden.[303]