Alcoholic beverage: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

===Fermented alcohols=== |

===Fermented alcohols=== |

||

{{main|Ethanol fermentation}} |

{{main|Ethanol fermentation}} |

||

It is well known that higher alcohols present in relatively high concentration in beer, wine, and spirits all can cause hangover symptoms. The fraction boiling above 95 °C (ethanol b.p. = 78 °C) is designated as fusel oil. This may be shown to contain up to 50 different components, where the chief constituents are isobutanol (2-methyl-1-propanol), propanol, and above all, the pair of isoamylalkohols: 2-methyl-1-butanol and 3-methyl-1-butanol.<ref>http://www.chemistryviews.org/details/ezine/1080019/Chemistry_of_a_Hangover__Alcohol_and_its_Consequences_Part_3.html</ref> |

|||

Alcohols other than [[ethanol]] have been found in traces in alcoholic beverages<ref>MERCK INDEX 10th Ed. 1983, Fusel Oils (entry 4195)</ref>; Note that [[methanol]] is ''not'' a [[fusel alcohol]] since it has only one carbon atom. During the past decade numerous values have been recorded for the higher alcohols in beers, and their effects of the flavour of beer has contrinued to receive considerable attention<ref>http://books.google.se/books?id=allg4XxlOM4C&pg=PA22&lpg=PA22&dq=2-Methyl-2-butanol+occurrence&source=bl&ots=Ped5CJ8BgX&sig=118Rxwke4Tvwh724RxCFmW4tKwU&hl=en&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=2-Methyl-2-butanol%20occurrence&f=false</ref> It is virtual possible to produce any by-product alcohol of ethanol fermentation alone: |

Alcohols other than [[ethanol]] have been found in traces in alcoholic beverages<ref>MERCK INDEX 10th Ed. 1983, Fusel Oils (entry 4195)</ref>; Note that [[methanol]] is ''not'' a [[fusel alcohol]] since it has only one carbon atom. During the past decade numerous values have been recorded for the higher alcohols in beers, and their effects of the flavour of beer has contrinued to receive considerable attention<ref>http://books.google.se/books?id=allg4XxlOM4C&pg=PA22&lpg=PA22&dq=2-Methyl-2-butanol+occurrence&source=bl&ots=Ped5CJ8BgX&sig=118Rxwke4Tvwh724RxCFmW4tKwU&hl=en&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=2-Methyl-2-butanol%20occurrence&f=false</ref> It is virtual possible to produce any by-product alcohol of ethanol fermentation alone: |

||

Revision as of 17:34, 19 January 2013

An alcoholic beverage is a drink containing ethanol, commonly known as alcohol. Alcoholic beverages are divided into three general classes: beers, wines, and spirits (or distilled beverage). They are legally consumed in most countries, and over 100 countries have laws regulating their production, sale, and consumption.[1] In particular, such laws specify the minimum age at which a person may legally buy or drink them. This minimum age varies between 16 and 25 years, depending upon the country and the type of drink. Most nations set it at 18 years of age.[1]

The production and consumption of alcohol occurs in most cultures of the world, from hunter-gatherer peoples to nation-states.[2][3] Alcoholic beverages are often an important part of social events in these cultures.

Alcohol is a psychoactive drug classified as depressant. The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) recently redefined the term "binge drinking" as any time one reaches a peak BAC of 0.08% or higher as opposed to some (arguably) arbitrary number of drinks in an evening.[4] A high blood alcohol content (BAC) is usually considered to be legal drunkenness because it reduces attention and slows reaction speed. However, alcohol can be addictive known as alcoholism. A single study found, if a society believes that intoxication leads to sexual behavior, rowdy behavior, or aggression, then people tend to act that way when intoxicated. But if a society believes that intoxication leads to relaxation and tranquil behavior, then it usually leads to those outcomes. Alcohol expectations vary within a society, so these outcomes are not certain.[5]

Alcohols

Alcohol is a general term for any organic compound in which a hydroxyl group (-O H) is bound to a carbon atom, which in turn may be bound to other carbon atoms and further hydrogens. Alcohols other than ethanol (such as propylene glycol and the sugar alcohols) appear in food and beverages. Methanol (one carbon), and the butanols (four carbons, four isomers) are commonly found toxic alcohols that should never be consumed, in any form.

Fermented alcohols

It is well known that higher alcohols present in relatively high concentration in beer, wine, and spirits all can cause hangover symptoms. The fraction boiling above 95 °C (ethanol b.p. = 78 °C) is designated as fusel oil. This may be shown to contain up to 50 different components, where the chief constituents are isobutanol (2-methyl-1-propanol), propanol, and above all, the pair of isoamylalkohols: 2-methyl-1-butanol and 3-methyl-1-butanol.[6]

Alcohols other than ethanol have been found in traces in alcoholic beverages[7]; Note that methanol is not a fusel alcohol since it has only one carbon atom. During the past decade numerous values have been recorded for the higher alcohols in beers, and their effects of the flavour of beer has contrinued to receive considerable attention[8] It is virtual possible to produce any by-product alcohol of ethanol fermentation alone:

| Alcohol | Other names | Oral toxicology on humans | Potency (Ethanol LD50:LD50 ratio) | LD50 in rat, oral[9] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | Ethyl alcohol, drinking alcohol | Safe: Ethanol is the active ingredient in common alcoholic beverages. | 1 | 7060 mg/kg |

| 1-Pentanol | n-pentanol, pentan-1-ol | ? | 1.2 | 5660 uL/kg |

| 1-Propanol | Propanol, n-propanol, or propan-1-ol | No epidemiological studies are available to assess the long-term effects, including the carcinogenicity, of 1-propanol in human beings. The most likely acute effects of 1-propanol in man are alcoholic intoxication and narcosis. The results of animal studies indicate that 1-propanol is 2 - 4 times as intoxicating as ethanol. Animal toxicity data are not adequate to make an evaluation of the human health risks associated with repeated or long-term exposure to 1-propanol. However, limited short-term rat studies suggest that oral exposure to 1-propanol is unlikely to pose a serious health hazard under the usual conditions of human exposure.[10] As of 2011, only one case of lethal 1-propanol poisoning was reported.[11]

Ethanol has been found to double the lifespans of worms feed 0.005% ethanol but does not markedly increase at higher concentrations. Supplementing starved cultures with n-propanol and n-butanol also extended lifespan.[12] |

3.8 | 1870 mg/kg |

| 2-Butanol | n-butyl alcohol, normal butanol, sec-butanol | ? | 3.2 | 2193 mg/kg |

| 2-Methyl-1-butanol (2M1B) | Active amyl alcohol | ? | ? | ? |

| 2-Methyl-1-propanol (2M1P) | Isobutanol, isobutyl alcohol | ? | 2.9 | 2460 mg/kg |

| 2-Pentanol | sec-amyl alcohol | ? | ? | ? |

| 3-methyl-1-butanol (3M1B) | Isoamyl alcohol, isopentanol, isopentyl alcohol | ? | 5.4 | 1300 mg/kg |

| 3-Pentanol | ? | ? | 3.8 | 1870 mg/kg |

| Methanol, methyl alcohol | Wood alcohol | Dangerous: Acute ingestion of as little as 4 to 10 mL of methanol may cause permanent blindness (Vale & Meredith, 1981; Bozza-Marrubini et al., 1987; Gossel & Bricker, 1984; Litovitz, 1986). However, methanol occurs only in trace quantities in some home brewing like Applejack. | 1.3 | 5628 mg/kg |

| 3-Methyl-2-butanol | sec-isoamyl alcohol | ? | ? | ? |

Ethanol

Ethanol (CH3CH2OH) is the active ingredient in alcoholic beverages (although novelty inebriating drinks have been made from alternate alcohols such as 2-Methyl-2-butanol[citation needed]). When produced for use in a beverage, ethanol is always produced by means of fermentation, i.e., the metabolism of carbohydrates by certain species of yeast in the absence of oxygen.

Liquor that contains 40% ABV (80 US proof) will catch fire if heated to about 79 °F (26 °C) and an ignition source is applied to it. This is called its flash point.[13] The flash point of pure alcohol is 63 °F (17 °C).[14] The flash points of alcohol concentrations from 10% ABV to 96% ABV are shown below:[15]

- 5%: 144 °F (62 °C)—beer

- 10%: 120 °F (49 °C)—wine

- 20%: 97 °F (36 °C)—fortified wine

- 30%: 84 °F (29 °C)

- 40%: 79 °F (26 °C)—typical whiskey

- 50%: 75 °F (24 °C)—strong whiskey

- 60%: 72 °F (22 °C)

- 70%: 70 °F (21 °C)—absinthe

- 80%: 68 °F (20 °C)

- 90%: 63 °F (17 °C)—neutral grain spirit

- 96%: 63 °F (17 °C)

Beverages that have a low concentration of alcohol will burn if sufficiently heated and an ignition source (such as an electric spark or a match) is applied to them. For example, the flash point of ordinary wine containing 12.5% alcohol is about 120 °F (49 °C).[13][16]

Novelty inebriating alcohols

- 2-Methyl-2-butanol (2M2B, amylene hydrate, or tert-amyl alcohol) - 2M2B has been used recreationally because of its lack of toxic aldehyde metabolites.[17][18] It is active in doses of 2,000-4,000 mg, making it some 20 times more potent than regular ethanol.[19][20]

- Methylpentynol

Beverages

Types

Beer and wine are produced by fermentation of sugar- or starch-containing plant material. Beverages produced by fermentation followed by distillation have a higher alcohol content and are known as liquor or spirits.

Beer

Beer is one of the world's oldest[2][21] and most widely consumed[3] alcoholic beverages, and the third most popular drink overall after water and tea.[22] It is produced by the brewing and fermentation of starches which are mainly derived from cereal grains — most commonly malted barley although wheat, maize (corn), and rice are also used.

Alcoholic beverages that are distilled after fermentation, or are fermented from non-cereal sources (such as grapes or honey), or are fermented from unmalted cereal grain are not classified as beer.

The two main types of beer are lager and ale. Ale is further classified into varieties such as pale ale, stout, and brown ale, whereas different types of lager include black lager, pilsener, and bock.

Most beer is flavored with hops, which add bitterness and act as a natural preservative. Other flavorings, such as fruits or herbs, may also be used.

The alcoholic strength of beer is usually 4% to 6% alcohol by volume (ABV), but it may be less than 2% or greater than 25%. Beers having an ABV of 60% (120 proof)[citation needed] have been produced by freezing brewed beer and removing water in the form of ice, a process referred to as "ice distilling".

Beer is part of the drinking culture of various nations and has acquired social traditions such as beer festivals, pub games, and pub crawling (sometimes known as bar hopping).

The basics of brewing beer are shared across national and cultural boundaries. The beer-brewing industry is global in scope, consisting of several dominant multinational companies and thousands of smaller producers, which range from regional breweries to microbreweries.

Wine

Wine is produced from grapes, and from fruits such as plums, cherries, or apples. Wine involves a longer fermentation process than beer and also a long aging process (months or years), resulting in an alcohol content of 9%–16% ABV. Sparkling wine can be made by means of a secondary fermentation.

Fortified wine is wine (such as port or sherry), to which a distilled beverage (usually brandy) has been added.

Spirits

Unsweetened, distilled, alcoholic beverages that have an alcohol content of at least 20% ABV are called spirits.[23] Spirits are produced by the distillation of a fermented base product. Distilling concentrates the alcohol and eliminates some of the congeners. For the most common distilled beverages, such as whiskey and vodka, the alcohol content is around 40%.

Spirits can be added to wines to create fortified wines, such as port and sherry.

Distilled alcoholic beverages were first recorded in Europe in the mid-12th century. By the early 14th century, they had spread throughout the European continent.[24] They also spread eastward from Europe, mainly due to the Mongols, and began to be seen in China no later than the 14th century.[citation needed]

Paracelsus gave alcohol its modern name, which is derived from an Arabic word that means “finely divided” (a reference to distillation).

Materials

The names of some alcoholic beverages are determined by their base material. In general, a beverage fermented from a grain mash will be called a beer. If the fermented mash is distilled, then the beverage is a spirit.

Wine and brandy are usually made from grapes but when they are made from another kind of fruit, they are distinguished as fruit wine or fruit brandy. The kind of fruit must be specified, such as "cherry brandy" or "plum wine."

Beer is made from barley or a blend of several grains.

Whiskey (or whisky) is made from grain or a blend of several grains. The type of whiskey (scotch, rye, bourbon, or corn) is determined by the primary grain.

Vodka is distilled from fermented grain. It is highly distilled so that it will contain less of the flavor of its base material. Gin is a similar distillate but it is flavored by juniper berries and sometimes by other herbs as well.

In the United States and Canada, cider often means unfermented apple juice (sometimes called sweet cider), and fermented apple juice is called hard cider. In the United Kingdom and Australia, cider refers to the alcoholic beverage.

Applejack is sometimes made by means of freeze distillation.

Grains

| Source | Name of fermented beverage | Name of distilled beverage |

|---|---|---|

| barley | beer, ale, barley wine | Scotch whisky, Irish whiskey, shōchū (mugijōchū) (Japan) |

| rye | rye beer, kvass | rye whiskey, vodka (Poland), Korn (Germany) |

| corn | chicha, corn beer, tesguino | Bourbon whiskey; and vodka (rarely) |

| sorghum | burukutu (Nigeria), pito (Ghana), merisa (southern Sudan), bilibili (Chad, Central African Republic, Cameroon) | maotai, gaoliang, certain other types of baijiu (China). |

| wheat | wheat beer | horilka (Ukraine), vodka, wheat whisky, weizenkorn (Germany) |

| rice | beer, brem (Bali), huangjiu and choujiu (China), Ruou gao (Vietnam), sake (Japan), sonti (India), makgeolli (Korea), tuak (Borneo Island), thwon (Nepal) | aila (Nepal), rice baijiu (China), shōchū (komejōchū) and awamori (Japan), soju (Korea) |

| millet | millet beer (Sub-Saharan Africa), tongba (Nepal, Tibet), boza (the Balkans, Turkey) | |

| buckwheat | shōchū (sobajōchū) (Japan) |

Fruit juice

| Source | Name of fermented beverage | Name of distilled beverage |

|---|---|---|

| juice of grapes, | wine | brandy, Cognac (France), Vermouth, Armagnac (France), Branntwein (Germany), pisco (Peru, Chile), Rakia (The Balkans, Turkey), singani (Bolivia), Arak (Syria, Lebanon, Jordan), törkölypálinka (Hungary) |

| juice of apples | cider (U.S.: "hard cider"), Apfelwein | applejack (or apple brandy), calvados, cider |

| juice of pears | perry, or pear cider; poiré (France) | Poire Williams, pear brandy, Eau-de-vie (France), pálinka (Hungary) |

| juice of plums | plum wine | slivovitz, țuică, umeshu, pálinka |

| juice of pineapples | tepache (Mexico) | |

| junipers | borovička (Slovakia) | |

| bananas or plantains | Chuoi hot (Vietnam), urgwagwa (Uganda, Rwanda), mbege (with millet malt; Tanzania), kasikisi (with sorghum malt; Democratic Republic of the Congo) | |

| gouqi | gouqi jiu (China) | gouqi jiu (China) |

| coconut | Toddy (Sri Lanka, India) | arrack, lambanog (Sri Lanka, India, Philippines) |

| ginger with sugar, ginger with raisins | ginger ale, ginger beer, ginger wine | |

| Myrica rubra | yangmei jiu (China) | yangmei jiu (China) |

| pomace | pomace wine | Raki/Ouzo/Pastis/Sambuca (Turkey/Greece/France/Italy), tsipouro/tsikoudia (Greece), grappa (Italy), Trester (Germany), marc (France), orujo (Spain), zivania (Cyprus), aguardente (Portugal), tescovină (Romania), Arak (Iraq) |

Vegetables

| Source | Name of fermented beverage | Name of distilled beverage |

|---|---|---|

| juice of ginger root | ginger beer (Botswana) | |

| potato | potato beer | horilka (Ukraine), vodka (Poland and Germany), akvavit (Scandinavia), poitín (poteen) (Ireland) |

| sweet potato | shōchū (imojōchū) (Japan), soju (Korea) | |

| cassava/manioc/yuca | nihamanchi (South America), kasiri (Sub-Saharan Africa), chicha (Ecuador) | |

| juice of sugarcane, or molasses | basi, betsa-betsa (regional) | rum (Caribbean), pinga or cachaça (Brasil), aguardiente, guaro |

| juice of agave | pulque | tequila, mezcal, raicilla |

Other ingredients

| Source | Name of fermented beverage | Name of distilled beverage |

|---|---|---|

| sap of palm | coyol wine (Central America), tembo (Sub-Saharan Africa), toddy (Indian subcontinent) | |

| sap of Arenga pinnata, Coconut, Borassus flabellifer | Tuak (Indonesia) | Arrack |

| honey | mead, horilka (Ukraine), tej (Ethiopia) | distilled mead (mead brandy or honey brandy) |

| milk | kumis, kefir, blaand | arkhi (Mongolia) |

| sugar | kilju and mead or sima (Finland) | shōchū (kokutō shōchū): made from brown sugar (Japan) |

Flavoring

Alcohol is a moderately good solvent for many fatty substances and essential oils. This attribute facilitates the use of flavoring and coloring compounds in alcoholic beverages, especially distilled beverages. Flavors may be naturally present in the beverage’s base material. Beer and wine may be flavored before fermentation. Spirits may be flavored before, during, or after distillation.

Sometimes flavor is obtained by allowing the beverage to stand for months or years in oak barrels, usually American or French oak.

A few brands of spirits have fruit or herbs inserted into the bottle at the time of bottling.

Standards

Alcohol concentration

The concentration of alcohol in a beverage is usually stated as the percentage of alcohol by volume (ABV) or as proof. In the United States, proof is twice the percentage of alcohol by volume at 60 degrees Fahrenheit (e.g. 80 proof = 40% ABV). Degrees proof were formerly used in the United Kingdom, where 100 degrees proof was equivalent to 57.1% ABV. Historically, this was the most dilute spirit that would sustain the combustion of gunpowder.

Ordinary distillation cannot produce alcohol of more than 95.6% ABV (191.2 proof) because at that point alcohol is an azeotrope with water. A spirit which contains a very high level of alcohol and does not contain any added flavoring is commonly called a neutral spirit. Generally, any distilled alcoholic beverage of 170 proof or higher is considered to be a neutral spirit.[25]

Most yeasts cannot reproduce when the concentration of alcohol is higher than about 18%, so that is the practical limit for the strength of fermented beverages such as wine, beer, and sake. However, some strains of yeast have been developed that can reproduce in solutions of up to 25% ABV.[citation needed]

Alcohol-free definition controversy

The term alcohol-free (eg alcohol-free beer) is often used to describe a product that contains 0% ABV; As such, it is permitted by Islam, and they are also popular in countries that enforce alcohol prohibition, such as Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Iran.

However, alcohol is legal in most countries of the world where alcohol culture also is prevalent. Laws vary in countries when beverages must indicate the strength but also what they define as alcohol-free; Experts calling the label “misleading” and a threat to recovering alcoholics.[26]

In the EU the labeling of beverages containing more than 1.2% by volume of alcohol must indicate the actual alcoholic strength by volume, i.e. showing the word "alcohol" or the abbreviation "alc." followed by the symbol "% vol."[27]

Most of the alcohol-free drinks sold in Sweden’s state-run liquor store monopoly Systembolaget actually contain alcohol, with experts calling the label “misleading” and a threat to recovering alcoholics.[26] Systembolaget define alcohol-free as a drink that contains a maximum of 0,5 percent alcohol by volume.[28] Interestingly, the drug policy of Sweden is based on zero tolerance.

Standard drinks

A standard drink is a notional drink that contains a specified amount of pure alcohol. The standard drink is used in many countries to quantify alcohol intake. It is usually expressed as a measure of beer, wine, or spirits. One standard drink always contains the same amount of alcohol regardless of serving size or the type of alcoholic beverage.

The standard drink varies significantly from country to country. For example, it is 7.62 ml (6 grams) of alcohol in Austria, but in Japan it is 25 ml (19.75 grams).

In the United Kingdom, there is a system of units of alcohol which serves as a guideline for alcohol consumption. A single unit of alcohol is defined as 10 ml. The number of units present in a typical drink is printed on bottles. The system is intended as an aid to people who are regulating the amount of alcohol they drink; it is not used to determine serving sizes.

In the United States, the standard drink contains 0.6 US fluid ounces (18 ml) of alcohol. This is approximately the amount of alcohol in a 12-US-fluid-ounce (350 ml) glass of beer, a 5-US-fluid-ounce (150 ml) glass of wine, or a 1.5-US-fluid-ounce (44 ml) glass of a 40% ABV (80 proof) spirit.

Serving sizes

In the United Kingdom, serving size in licensed premises is regulated under the Weights and Measures Act (1985). Spirits (gin, whisky, rum, and vodka) are sold in 25 ml or 35 ml quantities or multiples thereof.[29] Beer is typically served in pints (568 ml), but is also served in half-pints or third-pints.

In Ireland, the serving size of spirits is 35.5 ml or 71 ml. Beer is usually served in pints or half-pints ("glasses"). In the Netherlands and Belgium, standard servings are 250 and 500 ml for pilsner; 300 and 330 ml for ales.

The shape of a glass can have a significant effect on how much one pours. A Cornell University study of students and bartenders' pouring showed both groups pour more into short, wide glasses than into tall, slender glasses.[30] Aiming to pour one shot of alcohol (1.5 ounces or 44.3 ml), students on average poured 45.5 ml & 59.6 ml (30% more) respectively into the tall and short glasses. The bartenders scored similarly, on average pouring 20.5% more into the short glasses. More experienced bartenders were more accurate, pouring 10.3% less alcohol than less experienced bartenders. Practice reduced the tendency of both groups to over pour for tall, slender glasses but not for short, wide glasses. These misperceptions are attributed to two perceptual biases: (1) Estimating that tall, slender glasses have more volume than shorter, wider glasses; and (2) Over focusing on the height of the liquid and disregarding the width.

Alcohol consumption

History

Alcoholic beverages have been drunk by people around the world since ancient times. Reasons that have been proposed for drinking them include:

- They are part of a people's standard diet

- They are drunk for medical reasons

- For their relaxant effects

- For their euphoric effects

- For recreational purposes

- For artistic inspiration

- For their putative aphrodisiac effects

Archaeological record

Chemical analysis of traces absorbed and preserved in pottery jars from the neolithic village of Jiahu in Henan province in northern China has revealed that a mixed fermented beverage made from rice, honey, and fruit was being produced as early as 9,000 years ago. This is approximately the time when barley beer and grape wine were beginning to be made in the Middle East.

Recipes have been found on clay tablets and art in Mesopotamia that show people using straws to drink beer from large vats and pots.

The Hindu ayurvedic texts describe both the beneficial effects of alcoholic beverages and the consequences of intoxication and alcoholic diseases.

The medicinal use of alcohol was mentioned in Sumerian and Egyptian texts dating from about 2100 BC. The Hebrew Bible recommends giving alcoholic drinks to those who are dying or depressed, so that they can forget their misery (Proverbs 31:6-7).

Wine was consumed in Classical Greece at breakfast or at symposia, and in the 1st century BC it was part of the diet of most Roman citizens. Both the Greeks and the Romans generally drank diluted wine (the strength varying from 1 part wine and 1 part water, to 1 part wine and 4 parts water).

In Europe during the Middle Ages, beer, often of very low strength, was an everyday drink for all classes and ages of people. A document from that time mentions nuns having an allowance of six pints of ale each day. Cider and pomace wine were also widely available; grape wine was the prerogative of the higher classes.

By the time the Europeans reached the Americas in the 15th century, several native civilizations had developed alcoholic beverages. According to a post-conquest Aztec document, consumption of the local "wine" (pulque) was generally restricted to religious ceremonies but was freely allowed to those who were older than 70 years.

The natives of South America produced a beer-like beverage from cassava or maize, which had to be chewed before fermentation in order to turn the starch into sugar. (Beverages of this kind are known today as cauim or chicha.) This chewing technique was also used in ancient Japan to make sake from rice and other starchy crops.

Alcohol in American history

In the early 19th century, Americans had inherited a hearty drinking tradition. Many types of alcohol were consumed. One reason for this heavy drinking was attributed to an overabundance of corn on the western frontier, which encouraged the widespread production of cheap whiskey. It was at this time that alcohol became an important part of the American diet. In the 1820s, Americans drank seven gallons of alcohol per person annually.[31][32]

During the 19th century, Americans drank alcohol in two distinctive ways. One way was to drink small amounts daily and regularly, usually at home or alone. The other way consisted of communal binges. Groups of people would gather in a public place for elections, court sessions, militia musters, holiday celebrations, or neighborly festivities. Participants would typically drink until they became intoxicated.

Uses

In many countries, people drink alcoholic beverages at lunch and dinner. Studies have found that when food is eaten before drinking alcohol, alcohol absorption is reduced[33] and the rate at which alcohol is eliminated from the blood is increased. The mechanism for the faster alcohol elimination appears to be unrelated to the type of food. The likely mechanism is food-induced increases in alcohol-metabolizing enzymes and liver blood flow.[33]

At times and places of poor public sanitation (such as Medieval Europe), the consumption of alcoholic drinks was a way of avoiding water-borne diseases such as cholera. Small beer and faux wine, in particular, were used for this purpose. Although alcohol kills bacteria, its low concentration in these beverages would have had only a limited effect. More important was that the boiling of water (required for the brewing of beer) and the growth of yeast (required for fermentation of beer and wine) would tend to kill dangerous microorganisms. The alcohol content of these beverages allowed them to be stored for months or years in simple wood or clay containers without spoiling. For this reason, they were commonly kept aboard sailing vessels as an important (or even the sole) source of hydration for the crew, especially during the long voyages of the early modern period.

In cold climates, potent alcoholic beverages such as vodka are popularly seen as a way to “warm up” the body, possibly because alcohol is a quickly absorbed source of food energy and because it dilates peripheral blood vessels (peripherovascular dilation). This is a misconception because the “warmth” is actually caused by a transfer of heat from the body’s core to its extremities, where it is quickly lost to the environment. However, the perception alone may be welcomed when only comfort, rather than hypothermia, is a concern.

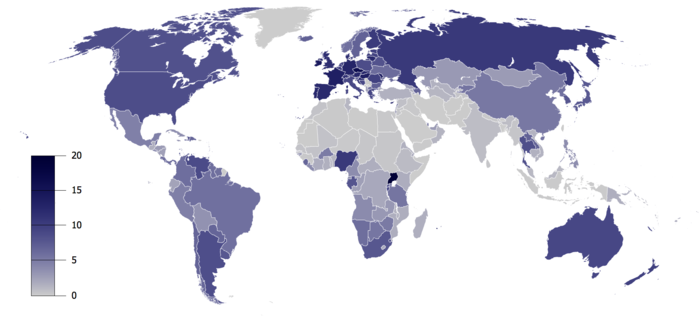

Alcohol consumption by country

Alcohol and health

Short-term effects of alcohol consumption include intoxication and dehydration. Long-term effects of alcohol include changes in the metabolism of the liver and brain and alcoholism (addiction to alcohol).

Alcohol intoxication affects the brain, causing slurred speech, clumsiness, and delayed reflexes. Alcohol stimulates insulin production, which speeds up glucose metabolism and can result in low blood sugar, causing irritability and (for diabetics) possible death. Severe alcohol poisoning can be fatal.

A blood alcohol content of .45% in test animals results in a median lethal dose of LD50. This means that .45% is the concentration of blood alcohol that is fatal in 50% of the test subjects. That is about six times the level of ordinary intoxication (0.08%), but vomiting or unconsciousness may occur much sooner in people who have a low tolerance for alcohol.[36] The high tolerance of chronic heavy drinkers may allow some of them to remain conscious at levels above .40%, although serious health dangers are incurred at this level.

Alcohol also limits the production of vasopressin (ADH) from the hypothalamus and the secretion of this hormone from the posterior pituitary gland. This is what causes severe dehydration when large amounts of alcohol are drunk. It also causes a high concentration of water in the urine and vomit and the intense thirst that goes along with a hangover.

Stress, hangovers and oral contraceptive pill may increase the desire for alcohol because these things will lower the level of testosterone and alcohol will acutely elevate it.[37] Tobacco has the same effect of increasing the craving for alcohol.[38]

Mortality rate

A report of the United States Centers for Disease Control estimated that medium and high consumption of alcohol led to 75,754 deaths in the U.S. in 2001. Low consumption of alcohol had some beneficial effects, so a net 59,180 deaths were attributed to alcohol.[39]

In the United Kingdom, heavy drinking is blamed for about 33,000 deaths a year.[40]

A study in Sweden found that 29% to 44% of "unnatural" deaths (those not caused by illness) were related to alcohol. The causes of death included murder, suicide, falls, traffic accidents, asphyxia, and intoxication.[41]

A global study found that 3.6% of all cancer cases worldwide are caused by alcohol drinking, resulting in 3.5% of all global cancer deaths.[42] A study in the United Kingdom found that alcohol causes about 6% of cancer deaths in the UK (9,000 deaths per year).[43]

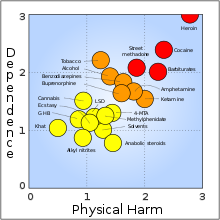

ISCD

A 2010 study by the Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs, led by David Nutt, Leslie King and Lawrence Phillips, asked drug-harm experts to rank a selection of illegal and legal drugs on various measures of harm both to the user and to others in society. These measures include damage to health, drug dependency, economic costs and crime. The researchers claim that the rankings are stable because they are based on so many different measures and would require significant discoveries about these drugs to affect the rankings.[44]

Despite being legal more often than the other drugs, alcohol was considered to be by far the most harmful; not only was it regarded as the most damaging to societies, it was also seen as the fourth most dangerous for the user. Most of the drugs were rated significantly less harmful than alcohol, with most of the harm befalling the user.

The authors explain that one of the limitation of this study is that drug harms are functions of their availability and legal status in the UK, and so other cultures' control systems could yield different rankings.

Alcohol expectations

Alcohol expectations are beliefs and attitudes that people have about the effects they will experience when drinking alcoholic beverages. They are largely beliefs about alcohol's effects on a person’s behaviors, abilities, and emotions. Some people believe that if alcohol expectations can be changed, then alcohol abuse might be reduced.[45]

The phenomenon of alcohol expectations recognizes that intoxication has real physiological consequences that alter a drinker's perception of space and time, reduce psychomotor skills, and disrupt equilibrium.[46] The manner and degree to which alcohol expectations interact with the physiological short-term effects of alcohol, resulting in specific behaviors, is unclear.

A single study found, if a society believes that intoxication leads to sexual behavior, rowdy behavior, or aggression, then people tend to act that way when intoxicated. But if a society believes that intoxication leads to relaxation and tranquil behavior, then it usually leads to those outcomes. Alcohol expectations vary within a society, so these outcomes are not certain.[5]

People tend to conform to social expectations, and some societies expect that drinking alcohol will cause disinhibition. However, in societies in which the people do not expect that alcohol will disinhibit, intoxication seldom leads to disinhibition and bad behavior.[46]

Alcohol expectations can operate in the absence of actual consumption of alcohol. Research in the United States over a period of decades has shown that men tend to become more sexually aroused when they think they have been drinking alcohol, — even when they have not been drinking it. Women report feeling more sexually aroused when they falsely believe the beverages they have been drinking contained alcohol (although one measure of their physiological arousal shows that they became less aroused).[citation needed]

Men tend to become more aggressive in laboratory studies in which they are drinking only tonic water but believe that it contains alcohol. They also become less aggressive when they believe they are drinking only tonic water, but are actually drinking tonic water that contains alcohol.[45]

Gender differences

There are many differences in alcohol consumption between men and women. The link between alcohol consumption, depression, and gender was examined by the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (Canada). The study found that women taking antidepressants consumed more alcohol than women who did not experience depression as well as men taking antidepressants. The researchers, Dr. Kathryn Graham and a PhD Student Agnes Massak analyzed the responses to a survey by 14,063 Canadian residents aged 18–76 years. The survey included measures of quantity, frequency of drinking, depression and antidepressants use, over the period of a year. The researchers used data from the GENACIS Canada survey, part of an international collaboration to investigate the influence of cultural variation on gender differences in alcohol use and related problems. The purpose of the study was to examine whether, like in other studies already conducted on male depression and alcohol consumption, depressed women also consumed less alcohol when taking anti-depressants.[47] According to the study, both men and women experiencing depression (but not on anti-depressants) drank more than non-depressed counterparts. Men taking antidepressants consumed significantly less alcohol than depressed men who did not use antidepressants. Non-depressed men consumed 436 drinks per year, compared to 579 drinks for depressed men not using antidepressants, and 414 drinks for depressed men who used antidepressants. Alcohol consumption remained higher whether the depressed women were taking anti-depressants or not. 179 drinks per year for non-depressed women, 235 drinks for depressed women not using antidepressants, and 264 drinks for depressed women who used antidepressants. The lead researcher argued that the study "suggests that the use of antidepressants is associated with lower alcohol consumption among men suffering from depression. But this does not appear to be true for women."[48]

Based on combined data from SAMHSA's 2004-2005 National Surveys on Drug Use & Health, the rate of past year alcohol dependence or abuse among persons aged 12 or older varied by level of alcohol use: 44.7% of past month heavy drinkers, 18.5% binge drinkers, 3.8% past month non-binge drinkers, and 1.3% of those who did not drink alcohol in the past month met the criteria for alcohol dependence or abuse in the past year. Males had higher rates than females for all measures of drinking in the past month: any alcohol use (57.5% vs. 45%), binge drinking (30.8% vs. 15.1%), and heavy alcohol use (10.5% vs. 3.3%), and males were twice as likely as females to have met the criteria for alcohol dependence or abuse in the past year (10.5% vs. 5.1%).[49]

Short-term effects of alcohol

Toxicology

Ethanol is metabolized into energy[clarify] in the liver. In the liver, the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase oxidizes ethanol into acetaldehyde, which is then further oxidized into harmless acetic acid by acetaldehyde dehydrogenase. Acetic acid is esterified with coenzyme A to produce acetyl CoA. Acetyl CoA carries the acetyl moiety into the citric acid cycle, which produces energy by oxidizing the acetyl moiety into carbon dioxide. Acetyl CoA can also be used for biosynthesis. Acetyl CoA is the energy-carrying intermediate common to the metabolism of sugars and fats; it is the product of glycolysis, the breakdown of glucose.[citation needed]

When compared to other alcohols, ethanol is only slightly toxic, with a lowest known lethal dose in humans of 1400 mg/kg (about 20 shots for a 100 kg person), and an LD50 of 9000 mg/kg (oral, rat). Nevertheless, accidental overdosing of alcoholic drinks, especially those containing a high percentage of alcohol, is risky, especially for women, lightweight persons, and children. These people have a smaller quantity of water in their bodies, so that the alcohol is less diluted. A blood alcohol concentration of 50 to 100 mg/dL may be considered legal drunkenness (laws vary by jurisdiction). The threshold of effects is at 22 mg/dL.[50]

In the human body, ethanol affects the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors and produces a depressant (neurochemical inhibitory) effect. Ethanol is similar to other sedative-hypnotics such as barbiturates and benzodiazepines both in its effect on the GABAA receptor, although its pharmacological profile is not identical. It has anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, hypnotic, and sedative actions similar to many other sedative-hypnotic drugs. Ethanol is also cross-tolerant with benzodiazepines and barbiturates.[51]

Alcohols are toxicated into the corresponding aldehydes and then into the corresponding carboxylic acids. These metabolic products cause a poisoning and acidosis. In the case of alcohols other than ethanol, the aldehydes and carboxylic acids are poisonous, and the acidosis can be lethal. In contrast, fatalities from ethanol are mainly found in extreme doses associated with the induction of unconsciousness or chronic addiction (alcoholism).[citation needed]

Excessive consumption of ethanol may cause a delayed effect that is called a hangover. Various factors contribute to it, including the toxication of ethanol to acetaldehyde, the direct toxic effects and toxication of impurities called congeners, and dehydration. The hangover starts after the euphoric effects of ethanol have subsided, typically in the night and morning after alcoholic drinks were consumed. However, the blood alcohol concentration may still be substantial and above the limit imposed for automobile drivers and operators of heavy equipment. The effects of a hangover subside over time. Various treatments to cure hangover have been suggested, many of them pseudoscientific.

Long-term effects of alcohol

Adverse effects of binge drinking (0.08% BAC or higher)

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) recently redefined the term "binge drinking" as any time one reaches a peak BAC of 0.08% or higher as opposed to some (arguably) arbitrary number of drinks in an evening.[4]

Alcoholism

Proclivity to alcoholism may be partially genetic. Persons who have this proclivity may have an atypical biochemical response to alcohol, although this is disputed.

Alcoholism can lead to malnutrition because it can alter digestion and the metabolism of most nutrients. Severe thiamine deficiency is common in alcoholism due to deficiency of folate, riboflavin, vitamin B6, and selenium ; this can lead to Korsakoff's syndrome. Alcoholism is also associated with a type of dementia called Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, which is caused by a deficiency in thiamine (vitamin B1).[52] Muscle cramps, nausea, loss of appetite, nerve disorders, and depression are common symptoms of alcoholism. Osteoporosis and bone fractures may occur due to deficiency of vitamin D.

Dementia

Excessive drinking has been linked to dementia; it is estimated that 10% to 24% of dementia cases are caused by alcohol consumption, with women being at greater risk than men.[53][54]

Alcoholism is associated with a type of dementia called Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome, which is caused by a deficiency in thiamine (vitamin B1).[52]

In people aged 55 or older, daily light-to-moderate drinking (one to three drinks) was associated with a 42% reduction in the probability of developing dementia and a 70% reduction in risk of vascular dementia.[55] The researchers suggest that alcohol may stimulate the release of acetylcholine in the hippocampus area of the brain.[55]

Cancer

Alcohol consumption has been linked with seven types of cancer: mouth cancer, pharyngeal cancer, oesophageal cancer, laryngeal cancer, breast cancer, bowel cancer and liver cancer.[43] Heavy drinkers are more likely to develop liver cancer due to cirrhosis of the liver.[43] The risk of developing cancer increases even with consumption of as little as three units of alcohol (one pint of lager or a large glass of wine) a day.[43]

A global study found that 3.6% of all cancer cases worldwide are caused by drinking alcohol, resulting in 3.5% of all global cancer deaths.[42] A study in the United Kingdom found that alcohol causes about 6% of cancer deaths in the UK (9,000 deaths per year).[43] A study in China found that alcohol causes about 4.40% of all cancer deaths and 3.63% of all cancer incidences.[56] For both men and women, the consumption of two or more drinks daily increases the risk of pancreatic cancer by 22%.[57]

Women who regularly consume low to moderate amounts of alcohol have an increased risk of cancer of the upper digestive tract, rectum, liver, and breast.[58][59]

Red wine contains resveratrol, which has some anti-cancer effect. However, based on studies done so far, there is no strong evidence that red wine protects against cancer in humans.[60]

Recent studies indicate that Asian populations are particularly prone to carcinogenic effects of alcohol. It's been noted that ethanol's byproducts in metabolism results in acetaldehyde. In non-Asian populations, an enzyme called alcohol dehydrogenase that quickly converts acetaldehyde into acetate. Asian populations have a variant form of alcohol dehydrogenase which prevents conversion of the acetaldehyde. This substance has been indicated to have strong interactions with DNA and thereby causing carcinogenic effects.[61][62]

Obesity

Biological and environmental factors are thought to contribute to alcoholism and obesity.[63] The physiologic commonalities between excessive eating and excessive alcohol drinking shed light on intervention strategies, such as pharmaceutical compounds that may help those who suffer from both. Some of the brain signaling proteins that mediate excessive eating and weight gain also mediate uncontrolled alcohol consumption.[63] Some physiological substrates that underlie food intake and alcohol intake have been identified. Melanocortins, a group of signaling proteins, are found to be involved in both excessive food intake and alcohol intake.[64]

Alcohol may contribute to obesity. A study found frequent, light drinkers (three to seven drinking days per week, one drink per drinking day) had lower BMIs than infrequent, but heavier drinkers.[65] Although calories in liquids containing ethanol may fail to trigger the physiologic mechanism that produces the feeling of fullness in the short term; long-term, frequent drinkers may compensate for energy derived from ethanol by eating less.[66]

Health effects of moderate drinking

Longevity

In a 2010 long-term study of an older population, the beneficial effects of moderate drinking were confirmed, but abstainers and heavy drinkers showed an increase of about 50% in mortality (even after controlling for confounding factors).[67]

Ethanol has been found to double the lifespans of worms feed 0.005% ethanol but does not markedly increase at higher concentrations. Supplementing starved cultures with n-propanol and n-butanol also extended lifespan.;[12] 1-Propanol (n-propanol) is thought to be similar to ethanol in its effects on human body, but 2-4 times more potent.

Diabetes

Daily consumption of a small amount of pure alcohol by older women may slow or prevent the onset of diabetes by lowering the level of blood glucose.[68] However, the researchers caution that the study used pure alcohol and that alcoholic beverages contain additives, including sugar, which would negate this effect.[68]

People with diabetes should avoid sugary drinks such as dessert wines and liqueurs.[69]

Heart disease

Alcohol consumption by the elderly results in increased longevity, which is almost entirely a result of lowered coronary heart disease.[70] A British study found that consumption of two units of alcohol (one regular glass of wine) daily by doctors aged 48+ years increased longevity by reducing the risk of death by ischaemic heart disease and respiratory disease.[71] Deaths for which alcohol consumption is known to increase risk accounted for only 5% of the total deaths, but this figure increased among those who drank more than two units of alcohol per day.[71]

One study found that men who drank moderate amounts of alcohol three or more times a week were up to 35% less likely to have a heart attack than non-drinkers, and men who increased their daily alcohol consumption by one drink over the 12 years of the study had a 22% lower risk of heart attack.[72]

Daily intake of one or two units of alcohol (a half or full standard glass of wine) is associated with a lower risk of coronary heart disease in men over 40, and in women who have been through menopause.[73] However, getting drunk one or more times per month put women at a significantly increased risk of heart attack, negating alcohol's potential protective effect.[74]

Increased longevity due to alcohol consumption is almost entirely the result of a reduced rate of coronary heart disease.[70]

Stroke

A study found that lifelong abstainers were 2.36 times more likely to suffer a stroke than those who regularly drank a moderate amount of alcohol beverages. Heavy drinkers were 2.88 times more likely to suffer a stroke than moderate drinkers.[75]

Alcohol laws

Alcohol laws are laws in relation to the manufacture, use, influence and sale of alcoholic beverages.

Alcohol laws often seek to reduce the availability of alcoholic beverages, often with the stated purpose of reducing the health and social side effect of their consumption. This can take the form of age limits for alcohol consumption, and distribution only in licensed stores or in monopoly stores. Often, this is combined with some form of alcohol taxation.

Alcohol and religion

Consumption

Some alcoholic beverages have been invested with religious significance, as in the ancient Greco-Roman religion, such as in the ecstatic rituals of Dionysus (also called Bacchus). Some have postulated that pagan religions actively promoted alcohol and drunkenness as a means of fostering fertility. Alcohol was believed to increase sexual desire and to make it easier to approach another person for sex. For example, Norse paganism considered alcohol to be the sap of Yggdrasil. Drunkenness was an important fertility rite in this religion.

Many Christian denominations use wine in the Eucharist or Communion and permit alcohol in moderation. Other denominations use unfermented grape juice in Communion and either abstain from alcohol by choice or prohibit it outright.

Judaism uses wine on Shabbat for Kiddush as well as in the Passover ceremony, Purim, and other religious ceremonies. The drinking of alcohol is allowed. Some Jewish texts, e.g. the Talmud, encourage moderate drinking on holidays (such as Purim) in order to make the occasion more joyous.

Prohibition

Some religions forbid, discourage, or restrict the drinking of alcoholic beverages for various reasons. These include Islam, Jainism, the Bahá'í Faith, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Seventh-day Adventist Church, the Church of Christ, Scientist, the United Pentecostal Church International, Theravada, most Mahayana schools of Buddhism, some Protestant denominations of Christianity, some sects of Taoism (Five Precepts (Taoism) and Ten Precepts (Taoism)), and Hinduism.

The Pali Canon, the scripture of Theravada Buddhism, depicts refraining from alcohol as essential to moral conduct because alcohol causes a loss of mindfulness. The fifth of the Five Precepts states, "Surā-meraya-majja-pamādaṭṭhānā veramaṇī sikkhāpadaṃ samādiyāmi." The English translation is, "I undertake to refrain from fermented drink that causes heedlessness." Technically this prohibition does not cover drugs other than alcohol. But its purport is not that alcohol is an evil but that the carelessness it produces creates bad karma. Therefore any substance (beyond tea or mild coffee) that affects one's mindfulness is considered to be covered by this prohibition.[citation needed]

See also

|

|

References

Notes

- ^ a b "Minimum Age Limits Worldwide". International Center for Alcohol Policies. Retrieved 2009-09-20.

- ^ a b Arnold, John P (2005). Origin and History of Beer and Brewing: From Prehistoric Times to the Beginning of Brewing Science and Technology. Cleveland, Ohio: Reprint Edition by BeerBooks. ISBN 0-9662084-1-2.

- ^ a b "Volume of World Beer Production". European Beer Guide. Archived from the original on 28 October 2006. Retrieved 2006-10-17.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Quick Stats: Binge Drinking." The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. April 2008.[1].

- ^ a b Marlatt, G. A.; Rosenow (1981). "The think-drink effect". Psychology Today. 15: 60–93.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|author-name-separator=(help); Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ http://www.chemistryviews.org/details/ezine/1080019/Chemistry_of_a_Hangover__Alcohol_and_its_Consequences_Part_3.html

- ^ MERCK INDEX 10th Ed. 1983, Fusel Oils (entry 4195)

- ^ http://books.google.se/books?id=allg4XxlOM4C&pg=PA22&lpg=PA22&dq=2-Methyl-2-butanol+occurrence&source=bl&ots=Ped5CJ8BgX&sig=118Rxwke4Tvwh724RxCFmW4tKwU&hl=en&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=2-Methyl-2-butanol%20occurrence&f=false

- ^ http://chem.sis.nlm.nih.gov/chemidplus/

- ^ http://www.inchem.org/documents/ehc/ehc/ehc102.htm#SectionNumber:1.8

- ^ "N-PROPANOL Health-Base Assessment and Recommendation for HEAC".

- ^ a b Castro PV, Khare S, Young BD, Clarke SG. "Caenorhabditis elegans Battling Starvation Stress: Low Levels of Ethanol Prolong Lifespan in L1 Larvae." PLoS ONE 7(1), 18th January 2012.

- ^ a b "Flash Point and Fire Point". Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ "Material Safety Data Sheet (Section 5)". Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- ^ "Flash points of ethanol-based water solutions". Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved June 23, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Robert L. Wolke (5 July 2006). "Combustible Combination". Washington Post. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- ^ "2-methyl-2-butanol - First Time - Nice, Euphoric Sedative, Few Negatives". Retrieved 2013-01-13.

- ^ "2-methyl-2-butanol "Vodka"". Retrieved 2013-01-13.

- ^ Hans Brandenberger & Robert A. A. Maes, ed. (1997). Analytical Toxicology for Clinical, Forensic and Pharmaceutical Chemists. p. 401. ISBN 3-11-010731-7.

- ^ D. W. Yandell; et al. (1888). "Amylene hydrate, a new hypnotic". The American Practitioner and News. 5. Lousville KY: John P. Morton & Co: 88–89.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ "Stone Age Had Booze" Popular Science, May 1932

- ^ Nelson, Max (2005). The Barbarian's Beverage: A History of Beer in Ancient Europe. books.google.co.uk. ISBN 978-0-415-31121-2. Retrieved 2009-02-22.

- ^ Lichine, Alexis. Alexis Lichine’s New Encyclopedia of Wines & Spirits (5th edition) (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1987), 707–709.

- ^ Forbes, Robert James (1970). A short history of the art of distillation: from the beginnings up to the death of Cellier Blumenthal. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-00617-1. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Lichine, Alexis. Alexis Lichine’s New Encyclopedia of Wines & Spirits (5th edition) (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1987), 365.

- ^ a b http://www.thelocal.se/44108/20121029/#.UPKD1hipNok

- ^ http://www.icap.org/table/alcoholbeveragelabeling

- ^ https://www.systembolaget.se/English/Product-range/Alcohol-free-products/

- ^ "fifedirect - Licensing & Regulations - Calling Time on Short Measures!". Fifefire.gov.uk. 2008-07-29. Retrieved 2010-02-11.

- ^ "Shape of glass and amount of alcohol poured: comparative study of effect of practice and concentration". BMJ. 331 (7531): 1512–14. 2005. doi:10.1136/bmj.331.7531.1512.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ George F. Will (2009-10-29). "A reality check on drug use". Washington Post. Washington Post. pp. A19.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Rorabaugh, W.J. (1981). The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-502990-1.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Ramchandani, V.A.; Kwo, P.Y.; Li, T-K. (2001). "Effect of Food and Food Composition on Alcohol Elimination Rates in Healthy Men and Women" (PDF). Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 41 (12): 1345–50. doi:10.1177/00912700122012814. PMID 11762562.

- ^ "Microsoft Word - global_alcohol_overview_260105.doc" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-02-11.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17382831, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17382831instead. - ^ Meyer, Jerold S. and Linda F. Quenzer. Psychopharmacology: Drugs, the Brain, and Behavior. Sinauer Associates, Inc: Sunderland, Massachusetts. 2005. Page 228.

- ^ helsinki.fi - Effect of alcohol on hormones in women, Helsinki 2001

- ^ helsinki.fi - Clinical studies on dependence and drug effects, ESBRA 2009

- ^ "Alcohol-Attributable Deaths and Years of Potential Life Lost — United States, 2001". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2004-09-24.

- ^ "Alcohol". BBC News. 2000-08-09.

- ^ "Alcohol linked to thousands of deaths". BBC News. 2000-07-14.

- ^ a b "Burden of alcohol-related cancer substantial". Abramson Cancer Center of the University of Pennsylvania. 2006-08-03.

- ^ a b c d e "Alcohol and cancer". Cancer Research UK.

- ^ http://www.economist.com/blogs/dailychart/2010/11/drugs_cause_most_harm

- ^ a b Grattan, Karen E.; Vogel-Sprott, M. (2001). "Maintaining Intentional Control of Behavior Under Alcohol". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 25 (2): 192–7. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2001.tb02198.x. PMID 11236832.

- ^ a b MacAndrew, C. and Edgerton. Drunken Comportment: A Social Explanation. Chicago: Aldine, 1969.

- ^ “Antidepressants Help Men, But Not Women, Decrease Alcohol Consumption.” Science Daily. Feb. 27, 2007.

- ^ Graham, Katherine and Massak, Agnes. “Alcohol consumption and the use of antidepressants.” UK Pubmed Central (2007). June 20, 2012.

- ^ “Gender differences in alcohol use and alcohol dependence or abuse: 2004 or 2005.” The NSDUH Report.Accessed June 22, 2012.

- ^ http://www.psychosomaticmedicine.org/cgi/reprint/28/4/570.pdf

- ^ Galanter, Marc; Kleber, Herbert D. (1 July 2008). The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Substance Abuse Treatment (4th ed.). United States of America: American Psychiatric Publishing Inc. p. 114. ISBN 978-1-58562-276-4.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - ^ a b Oscar-Berman M, Marinkovic K (2003). "Alcoholism and the brain: an overview". Alcohol Res Health. 27 (2): 125–33. PMID 15303622. Free full-text.

- ^ "Alcohol 'major cause of dementia'". National Health Service. 2008-05-11.

- ^ Campbell, Denis (2009-05-10). "Binge drinking 'increases risk' of dementia". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 2010-04-07.

- ^ a b "Alcohol 'could reduce dementia risk'". BBC News. 2002-01-25.

- ^ Liang, H.; Wang, Jianbing; Xiao, Huijuan; Wang, Ding; Wei, Wenqiang; Qiao, Youlin; Boffetta, Paolo (2010). "Estimation of cancer incidence and mortality attributable to alcohol drinking in China". BMC Public Health. 10 (1): 730. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-730.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Alcohol Consumption May Increase Pancreatic Cancer Risk". Medical News Today. 2009-03-04.

- ^ "Moderate Alcohol Consumption Increases Risk of Cancer in Women". 2009-03-10.

- ^ "Alcohol Consumption May Increase Pancreatic Cancer Risk". Medicalnewstoday.com. Retrieved 2010-02-11.

- ^ "Can alcohol be good for you?". Cancer Research UK.

- ^ http://www.kurzweilai.net/alcohol-may-boost-risk-of-cancer-for-asians

- ^ Silvia Balbo, Lei Meng, Robin L. Bliss, Joni A. Jensen, Dorothy K. Hatsukami, Stephen S. Hecht, Kinetics of DNA Adduct Formation in the Oral Cavity after Drinking Alcohol, Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 2012, DOI: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-1175

- ^ a b UNC Bowles Center for Alcohol Studies. Alcoholism and Obesity: Overlapping Brain Pathways? Center Line. Vol 14, 2003.

- ^ Thiele et al. Overlapping Peptide Control of Alcohol Self-Administration and Feeding. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, Vol 28, No 2, 2004: pp 288–294.

- ^ Breslow et al. Drinking Patterns and Body Mass Index in Never Smokers: National Health Interview Survey, 1997–2001. Am J Epidemiol 2005;161:368–376.

- ^ Cordain et al. Influence of moderate daily wine consumption on body weight regulation and metabolism in healthy free-living males. J Am Coll Nutr 1997;16:134–9.

- ^ Holahan, Charles J.; Schutte, Kathleen K.; Brennan, Penny L.; Holahan, Carole K.; Moos, Bernice S.; Moos, Rudolf H. (2010). "Late-Life Alcohol Consumption and 20-Year Mortality". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 34 (11): 1961–71. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01286.x. PMID 20735372.

- ^ a b "Alcohol may prevent diabetes". BBC News. 2002-05-15.

- ^ Dr Roger Henderson, GP (2006-01-17). "Alcohol and diabetes". Net Doctor.

- ^ a b Klatsky, A L; Friedman, G D (1995). "Alcohol and longevity". American Journal of Public Health. 85 (1): 16–8. doi:10.2105/AJPH.85.1.16. PMC 1615277. PMID 7832254.

- ^ a b Doll, R.; Peto, R; Boreham, J; Sutherland, I (2004). "Mortality in relation to alcohol consumption: a prospective study among male British doctors". International Journal of Epidemiology. 34 (1): 199–204. doi:10.1093/ije/dyh369. PMID 15647313.

- ^ "Frequent tipple cuts heart risk". BBC News. 2008-01-09.

- ^ "Alcohol and heart disease". British Heart Foundation.

- ^ "Moderate Drinking Lowers Women's Risk Of Heart Attack". Science Daily. 2007-05-25.

- ^ Rodgers, H; Aitken, PD; French, JM; Curless, RH; Bates, D; James, OF (1993). "Alcohol and stroke. A case-control study of drinking habits past and present". Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 24 (10): 1473–7. PMID 8378949.

External links

- Alcohol, Health-EU Portal

- BBC Headroom: Drinking too much?

- International Center for Alcohol Policies — Website

- International Center for Alcohol Policies — List of Tables

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism - What Is a Standard Drink?