Military history of Nova Scotia: Difference between revisions

Hantsheroes (talk | contribs) |

Hantsheroes (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 228: | Line 228: | ||

[[File:WinstonChurchillHalfaxNovaScotia.JPG|thumb|[[Winston Churchill]] by [[Oscar Nemon]]]] |

[[File:WinstonChurchillHalfaxNovaScotia.JPG|thumb|[[Winston Churchill]] by [[Oscar Nemon]]]] |

||

During [[World War II]],thousands of Nova Scotians went overseas. One Nova Scotian, [[Mona Louise Parsons]], joined the [[Dutch resistance]] and was eventually captured and imprisoned by the [[Nazis]] for almost four years. |

During [[World War II]],thousands of Nova Scotians went overseas. One Nova Scotian, [[Mona Louise Parsons]], joined the [[Dutch resistance]] and was eventually captured and imprisoned by the [[Nazis]] for almost four years. |

||

== Notable Nova Scotian Military Figures == |

|||

=== 17-18 Century === |

|||

<gallery> |

|||

File: Old Point Monument, Madison, ME.jpg|Grave of [[Sébastien Rale]] |

|||

File:Jean-BaptisteCopeSignatureJPEG.jpg| Chief [[Jean-Baptiste Cope]] |

|||

File:Abbe Le Loutre.jpg| Father [[Jean-Louis Le Loutre]] |

|||

File:File:Joseph Broussard Beausoleil acadian HRoe.jpg|Acadian [[Joseph Broussard]] |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

=== 19th Century === |

|||

<gallery> |

|||

File:WilliamParryWallisByRobertField.jpg|[[Provo Wallis]] |

|||

File:WilliamFenswickWilliamsNSHouseOfAssembleyByWilliam Gush.jpg| Nova Scotian [[Sir William Williams, 1st Baronet, of Kars]] by [[William Gush]] |

|||

File:JohnInglisByWilliamGushNSProvinceHouse.JPG|Nova Scotian Sir [[John Eardley Inglis]] by [[William Gush]] |

|||

File:William Hall VC.jpg|[[William Hall (VC)]] |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

=== Also See === |

|||

* Chief [[Madockawando]] |

|||

==External Links== |

==External Links== |

||

Revision as of 09:45, 9 August 2012

Nova Scotia (also known as Mi'kma'ki and Acadia) is a Canadian province located in Canada's Maritimes. The region was initially occupied by Mi'kmaq. During the first 150 years of European settlement, the colony was primarily made up of Catholic Acadians, Maliseet and Mi'kmaq. During this time period, there were six colonial wars that took place in Nova Scotia over a seventy-four year period (see the French and Indian Wars as well as Father Rale's War and Father Le Loutre's War). These wars were fought between New England and New France and their respective native allies before the British defeated the French in North America (1763). During these wars, Acadians, Mi'kmaq and Maliseet from the region fought to protect the border of Acadia from New England. They fought the war on two fronts: the southern border of Acadia, which New France defined as the Kennebec River in southern Maine.[1] The other front was in Nova Scotia and involved preventing New Englanders from taking the capital of Acadia, Port Royal (See Queen Anne's War), establishing themselves at Canso (See Father Rale's War) and founding Halifax (see Father Le Loutre's War).

The colonial history of Nova Scotia includes the present-day Canadian Maritime provinces and the northern part of Maine (Sunbury County, Nova Scotia), all of which were at one time part of Nova Scotia. In 1763 Cape Breton Island and St. John's Island (now Prince Edward Island) became part of Nova Scotia. In 1769, St. John's Island became a separate colony. Nova Scotia included present-day New Brunswick until that province was established in 1784.[2]

Seventeenth century

Port Royal established

The first European settlement in Nova Scotia was established in 1605. The French, led by Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Monts established the first capital for the colony Acadia at Port Royal.[3] Other than a few trading posts around the province, for the next seventy-five years, Port Royal was virtually the only European settlement in Nova Scotia. Port Royal (later renamed Annapolis Royal) remained the capital of Acadia and later Nova Scotia for almost 150 years, prior to the founding of Halifax in 1749.

Approximately seventy-five years after Port Royal was founded, Acadians migrated from the capital and established what would become the other major Acadian settlements before the Expulsion of the Acadians: Grand Pré, Chignecto, Cobequid and Pisiguit.

Until the Conquest of Acadia, the English made six attempts to conquer Acadia by defeating the capital. They finally defeated the French in the Siege of Port Royal in 1710. Over the following fifty years, the French and their allies made six unsuccessful military attempts to regain the capital.[4]

Scottish and French Conflict

From 1629-1632, Nova Scotia briefly became a Scottish colony. Sir William Alexander of Menstrie Castle, Scotland claimed mainland Nova Scotia and settled at Port Royal, while Ochiltree claimed Ile Royale (present-day Cape Breton Island) and settled at Baleine, Nova Scotia. There were three battles between the Scottish and the French: the Raid on St. John (1632), the Siege of Baleine (1629) as well as Siege of Cap de Sable (present-day Port La Tour, Nova Scotia) (1630). Nova Scotia was returned to France through a treaty.[5]

The French quickly defeated the Scottish at Baleine and established settlements on Ile Royale at present day Englishtown (1629) and St. Peter's (1630). These two settlements remained the only settlements on the island until they were abandoned by Nicolas Denys in 1659. Ile Royale then remained vacant for more than fifty years until the communities were re-established when Louisbourg was established in 1713.

Civil War in Acadia

Acadia was plunged into what some historians have described as a civil war in Acadia (1640–1645). The war was between Port Royal, where Governor of Acadia Charles de Menou d'Aulnay de Charnisay was stationed, and present-day Saint John, New Brunswick, where Governor of Acadia. Charles de Saint-Étienne de la Tour was stationed.[6]

In the war, there were four major battles. la Tour attacked d'Aulnay at Port Royal in 1640.[7] In response to the attack, D'Aulnay sailed out of Port Royal to establish a five month blockade of La Tour's fort at Saint John, which La Tour eventually defeated (1643). La Tour attacked d'Aulnay again at Port Royal in 1643. d'Aulnay and Port Royal ultimately won the war against La Tour with the 1645 siege of Saint John.[8] After d'Aulnay died (1650), La Tour re-established himself in Acadia.

Wabanaki Confederacy

In response to King Phillips War in New England, the Mi'kmaq and Maliseet people from this region joined the Wabanaki Confederacy to form a political and military alliance with New France.[9] The Mi'kmaq and Maliseet were very significant military allies to New France through six wars.

King William's War

During King William's War, the Mi'kmaq, Acadians and Maliseet participated in defending Acadia at its border with New England, which New France defined as the Kennebec River in southern Maine.[1] Toward this end, the Maliseet from their headquarters at Meductic on the Saint John River, joined the New France expedition against present-day Bristol, Maine (the Siege of Pemaquid (1689)), Salmon Falls and present-day Portland, Maine. In response, the New Englanders retaliated by attacking Port Royal and present-day Guysborough. In 1694, the Maliseet participated in the Raid on Oyster River at present-day Durham, New Hampshire. Two years later, New France, led by Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville, returned and fought a naval battle in the Bay of Fundy before moving on to raid Bristol, Maine again. In retaliation, the New Englanders, led by Benjamin Church, engaged in a Raid on Chignecto (1696) and the siege of the Capital of Acadia at Fort Nashwaak.

At the end of the war England returned the territory to France in the Treaty of Ryswick and the borders of Acadia remained the same.

Eighteenth century

Queen Anne's War

During Queen Anne's War, the Mi'kmaq, Acadians and Maliseet participated again in defending Acadia at its border against New England. They made numerous raids on New England settlements along the border in the Northeast Coast Campaign, the most famous being the Raid on Deerfield. In retaliation, Major Benjamin Church went on his fifth and final expedition to Acadia. He raided present-day Castine, Maine and then continued on by conducting raids against Grand Pre, Pisiquid and Chignecto. A few years later, defeated in the Siege of Pemaquid (1696), Captain March made an unsuccessful siege on the Capital of Acadia, Port Royal (1707). The New Englanders were successful with the Siege of Port Royal (1710), while the Wabanaki Conferacy were successful in the near-by Battle of Bloody Creek in 1711.

During Queen Anne's War, the Conquest of Acadia (1710) was confirmed by the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713. Acadia was defined as mainland-Nova Scotia by the French. Present-day New Brunswick and most of Maine remained contested territory, while New England conceded present-day Prince Edward Island and Cape Breton Island, which France quickly renamed Île St Jean and Île Royale (Cape Breton Island) respectively. On the latter island, the French established a fortress at Louisbourg to guard the sea approaches to Quebec.

Father Rale's War

During the excalation that proceeded Father Rale's War (1722–1725), Mi'kmaq raided the new fort at Canso, Nova Scotia (1720). Under potential siege, in May 1722, Lieutenant Governor John Doucett took 22 Mi'kmaq hostage at Annapolis Royal to prevent the capital from being attacked.[10] In July 1722 the Abenaki and Mi'kmaq created a blockade of Annapolis Royal, with the intent of starving the capital.[11] The natives captured 18 fishing vessels and prisoners from present-day Yarmouth to Canso. They also seized prisoners and vessels from the Bay of Fundy.

As a result of the escalating conflict, Massachusetts Governor Samuel Shute officially declared war on July 22, 1722.[12] The first battle of Father Rale's War happened in the Nova Scotia theatre.[13] In response to the blockade of Annapolis Royal, at the end of July 1722, New England launched a campaign to end the blockade and retrieve over 86 New England prisoners taken by the natives. One of these operations resulted in the Battle at Jeddore.[14] The next was a raid on Canso in 1723.[15] Then in July 1724 when a group of sixty Mikmaq and Maliseets raided Annapolis Royal.[16]

The treaty that ended the war marked a significant shift in European relations with the Mi'kmaq and Maliseet. For the first time a European Empire formally acknowledged that its dominion over Nova Scotia would have to be negotiated with the region's indigenous inhabitants. The treaty was invoked as recently as 1999 in the Donald Marshall case.[17]

King George's War

News of war declarations reached the French fortress at Louisbourg first, on May 3, 1744, and the forces there wasted little time in beginning hostilities. Concerned about their overland supply lines to Quebec, they first raided the British fishing port of Canso on May 23, and then organized an attack on Annapolis Royal, then the capital of Nova Scotia. However, French forces were delayed in departing Louisbourg, and their Mi'kmaq and Maliseet allies decided to attack on their own in early July. Annapolis had received news of the war declaration, and was somewhat prepared when the Indians began besieging Fort Anne. Lacking heavy weapons, the Indians withdrew after a few days. Then, in mid-August, a larger French force arrived before Fort Anne, but was also unable to mount an effective attack or siege against the garrison, which had received supplies and reinforcements from Massachusetts. In 1745, British colonial forces conducted the Siege of Port Toulouse (St. Peter's) and then captured Fortress Louisbourg after a siege of six weeks. France launched a major expedition to recover Acadia in 1746. Beset by storms, disease, and finally the death of its commander, the Duc d'Anville, it returned to France in tatters without reaching its objective.

Father Le Loutre's War

Despite the British Conquest of Acadia in 1710, Nova Scotia remained primarily occupied by Catholic Acadians and Mi'kmaq. To prevent the establishment of Protestant settlements in the region, Mi'kmaq raided the early British settlements of present-day Shelburne (1715) and Canso (1720). A generation later, Father Le Loutre's War began when Edward Cornwallis arrived to establish Halifax with 13 transports on June 21, 1749.[18] By unilaterally establishing Halifax the British were violating earlier treaties with the Mi'kmaq (1726), which were signed after Father Rale's War.[19] The British quickly began to build other settlements. To guard against Mi'kmaq, Acadian and French attacks on the new Protestant settlements, British fortifications were erected in Halifax (Citadel Hill) (1749), Dartmouth (1750), Bedford (Fort Sackville) (1751), Lunenburg (1753) and Lawrencetown (1754).[20] There were numerous Mi'kmaq and Acadian raids on these villages such as the Raid on Dartmouth (1751).

Within 18 months of establishing Halifax, the British also took firm control of peninsula Nova Scotia by building fortifications in all the major Acadian communities: present-day Windsor (Fort Edward); Grand Pre (Fort Vieux Logis) and Chignecto (Fort Lawrence). (A British fort already existed at the other major Acadian centre of Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia. Cobequid remained without a fort.)[20] There were numerous Mi'kmaq and Acadian raids on these fortifications such as the Siege of Grand Pre.

French and Indian War

The final colonial war was the French and Indian War. The British Conquest of Acadia happened in 1710. Over the next forty-five years the Acadians refused to sign an unconditional oath of allegiance to Britain. During this time period Acadians participated in various militia operations against the British and maintained vital supply lines to the French Fortress of Louisbourg and Fort Beausejour.[21]

During the French and Indian War, the British sought to neutralize any military threat Acadians posed and to interrupt the vital supply lines Acadians provided to Louisbourg by deporting Acadians from Acadia.[22]

The British began the Expulsion of the Acadians with the Bay of Fundy Campaign (1755). Over the next nine years over 12,000 Acadians were removed from Nova Scotia.[23] During the various campaigns of the expulsion, the Acadian and Native resistance to the British intensified.

British deportation campaigns

Bay of Fundy (1755)

The first wave of the expulsion began on August 10, 1755, with the Bay of Fundy Campaign (1755) during the French and Indian War.[24] The British ordered the expulsion of the Acadians after the Battle of Beausejour (1755). The Campaign started at Chignecto and then quickly moved to Grand Pre, Piziquid (Falmouth/ Windsor, Nova Scotia) and finally Annapolis Royal.[25]

On November 17, 1755, during the Bay of Fundy Campaign at Chignecto, George Scott took 700 troops and attacked twenty houses at Memramcook. They arrested the Acadians who remained and killed two hundred head of livestock, to deprive the French of supplies.[26] Many Acadians tried to escape the Expulsion by retreating to St. John and Petitcodiac rivers, and the Miramichi in New Brunswick. The British cleared the Acadians from these areas in the later campaigns of Petitcodiac River, St. John River, and the Gulf of St. Lawrence in 1758.

Cape Sable

Cape Sable included Port La Tour and the surrounding area (a much larger area than simply Cape Sable Island). In April 1756, Major Preble and his New England troops, on their return to Boston, raided a settlement near Port La Tour and captured 72 men, women and children.[27]

In the late summer of 1758, Major Henry Fletcher led the 35th regiment and a company of Gorham's Rangers to Cape Sable. He cordoned off the cape and sent his men through it. One hundred Acadians and Father Jean Baptistee de Gray surrendered, while about 130 Acadians and seven Mi'kmaq escaped. The Acadian prisoners were taken to Georges Island in Halifax Harbour.[28]

En route to the St. John River Campaign in September 1758, Moncton sent Major Roger Morris, in command of two men-of-war and transport ships with 325 soldiers, to deport more Acadians. On October 28, his troops sent the women and children to Georges Island. The men were kept behind and forced to work with troops to destroy their village. On October 31, they were also sent to Halifax.[29] In the spring of 1759, Joseph Gorham and his rangers arrived to take prisoner the remaining 151 Acadians. They reached Georges Island with them on June 29.[30]

Ile St. Jean and Ile Royale

The second wave of the Deportation began with the French defeat at the Siege of Louisbourg (1758). Thousands of Acadians were deported from Ile Saint-Jean (Prince Edward Island) and Ile Royale (Cape Breton). The Ile Saint-Jean Campaign resulted in the largest percentage of deaths of the Acadians deported. The highest single event total of fatalities during the Deportation occurred with the sinking of the Violet, with about 280 persons aboard, and the Duke William, with over 360 persons aboard.[31] By the time the second wave of the expulsion had begun, the British had discarded their policy of relocating the Catholic, French-speaking colonists to the Thirteen Colonies. They deported them directly to France.[32] In 1758, hundreds of Ile Royale Acadians fled to one of Boishebert's refugee camps south of Baie des Chaleurs.[33]

Petitcodiac River Campaign

This was a series of British military operations from June to November 1758 to deport the Acadians who either lived along the river or had taken refuge there from earlier deportation operations, such as the Ile Saint-Jean Campaign. Benoni Danks and Joseph Gorham's Rangers carried out the operation.[25]

Contrary to Governor Lawrence's direction, New England Ranger Danks engaged in frontier warfare against the Acadians. On July 1, 1758, Danks himself began to pursue the Acadians on the Petiticodiac. They arrived at present day Moncton and Danks’ Rangers ambushed about thirty Acadians, who were led by Joseph Broussard (Beausoleil). Many were driven into the river, three of them were killed and scalped, and others were captured. Broussard was seriously wounded.[34] Danks reported that the scalps were Mi’kmaq and received payment for them. Thereafter, he went down in local lore as “one of the most reckless and brutal” of the Rangers.[35]

St. John River Campaign

Colonel Robert Monckton led a force of 1150 British soldiers to destroy the Acadian settlements along the banks of the Saint John River until they reached the largest village of Sainte-Anne des Pays-Bas (present day Fredericton, New Brunswick) in February 1759.[36] Monckton was accompanied by New England Rangers led by Joseph Goreham, Captain Benoni Danks, Moses Hazen and George Scott.[37] The British started at the bottom of the river with raiding Kennebecais and Managoueche (City of St. John), where the British built Fort Frederick. Then they moved up the river and raided Grimross (Gagetown, New Brunswick), Jemseg, and finally they reached Sainte-Anne des Pays-Bas.[37]

Contrary to Governor Lawrence's direction, New England Ranger Lieutenant Hazen engaged in frontier warfare against the Acadians in what has become known as the "Ste Anne's Massacre". On 18 February 1759, Lieutenant Hazen and about fifteen men arrived at Sainte-Anne des Pays-Bas. The Rangers pillaged and burned the village of 147 buildings, two Mass-houses, besides all the barns and stables. The Rangers burned a large store-house, and with a large quantity of hay, wheat, peas, oats, etc., killing 212 horses, about 5 head of cattle, a large number of hogs and so forth. They also burned the church (located just west of Old Government House, Fredericton).[38]

As well, the rangers tortured and scalped six Acadians and took six prisoners.[38] There is a written record of one of the Acadian survivors Joseph Godin-Bellefontaine. He reported that the Rangers restrained him and then massacred his family in front of him. There are other primary sources that support his assertions.[39]

Gulf of St. Lawrence Campaign

In the Gulf of St. Lawrence Campaign (also known as the Gaspee Expedition), British forces raided French villages along present-day New Brunswick and the Gaspé Peninsula coast of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. Sir Charles Hardy and Brigadier-General James Wolfe commanded the naval and military forces, respectively. After the Siege of Louisbourg (1758), Wolfe and Hardy led a force of 1500 troops in nine vessels to the Gaspé Bay arriving there on September 5. From there they dispatched troops to Miramichi Bay (Sept. 12), Grande-Rivière, Quebec and Pabos (Sept. 13), and Mont-Louis, Quebec (Sept. 14). Over the following weeks, Sir Charles Hardy took four sloops or schooners, destroyed about 200 fishing vessels, and took about 200 prisoners.[40]

Restigouche

The Acadians took refuge along the Baie des Chaleurs and the Restigouche River.[41] Boishébert had a refugee camp at Petit-Rochelle (which was located perhaps near present-day Pointe-à-la-Croix, Quebec).[42] The year after the Battle of Restigouche, in late 1761, Captain Roderick Mackenzie and his force captured over 330 Acadians at Boishebert's camp.[43]

Halifax

After the French conquered St. John's, Newfoundland in June 1762, the success galvanized both the Acadians and Natives. They began gathering in large numbers at various points throughout the province and behaving in a confident and, according to the British,"insolent fashion". Officials were especially alarmed when Natives concentrated close to the two principal towns in the province, Halifax and Lunenburg, where there were also large groups of Acadians. The government organized an expulsion of 1300 people, shipping them to Boston. The government of Massachusetts refused the Acadians permission to land and sent them back to Halifax.[44]

Before the deportation, Acadian population was estimated at 14,000 Acadians. Most were deported.[45] Some Acadians escaped to Quebec, or hid among the Mi'kmaq or in the countryside, to avoid deportation until the situation settled down.[46]

The war ended and Britain had gained control over the entire Maritime region.

Acadian, Maliseet and Mi’kmaq resistance

During the expulsion, French Officer Charles Deschamps de Boishébert led the Mi'kmaq and the Acadians in a guerrilla war against the British.[47] According to Louisbourg account books, by late 1756, the French had regularly dispensed supplies to 700 Natives. From 1756 to the fall of Louisbourg in 1758, the French made regular payments to Chief Jean-Baptiste Cope and other natives for British scalps.[48]

Annapolis (Fort Anne)

The Acadians and Mi’kmaq fought in the Annapolis region. They were victorious in the Battle of Bloody Creek (1757).[49] Acadians being deported from Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia on the ship Pembroke rebelled against the British crew, took over the ship and sailed to land.

In December 1757, while cutting firewood near Fort Anne, John Weatherspoon was captured by Indians (presumably Mi'kmaq) and carried away to the mouth of the Miramichi River. From there he was eventually sold or traded to the French and taken to Quebec, where he was held until late in 1759 and the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, when General Wolfe's forces prevailed.[50]

About 50 or 60 Acadians who escaped the initial deportation are reported to have made their way to the Cape Sable region (which included south western Nova Scotia). From there, they participated in numerous raids on Lunenburg, Nova Scotia.[51]

Piziquid (Fort Edward)

In the April 1757, a band of Acadian and Mi'kmaq raided a warehouse near Fort Edward, killing thirteen British soldiers. After loading with what provisions they could carry, they set fire to the building.[52]

Chignecto (Fort Cumberland)

The Acadians and Mi’kmaq also resisted in the Chignecto region. They were victorious in the Battle of Petitcodiac (1755).[53] In the spring of 1756, a wood-gathering party from Fort Monckton (former Fort Gaspareaux), was ambushed and nine were scalped.[54] In the April 1757, after raiding Fort Edward, the same band of Acadian and Mi'kmaq partisans raided Fort Cumberland, killing and scalping two men and taking two prisoners.[55] July 20, 1757 Mi'kmaq killed 23 and captured two of Gorham's rangers outside Fort Cumberland near present-day Jolicure, New Brunswick.[56] In March 1758, forty Acadian and Mi'kmaq attacked a schooner at Fort Cumberland and killed its master and two sailors.[57] In the winter of 1759, the Mi'kmaq ambushed five British soldiers on patrol while they were crossing a bridge near Fort Cumberland. They were ritually scalped and their bodies mutilated as was common in frontier warfare.[58] During the night of 4 April 1759, using canoes, a force of Acadians and French captured the transport. At dawn they attacked the ship Moncton and chased it for five hours down the Bay of Fundy. Although the Moncton escaped, it’s crew suffered one killed and two wounded.[59]

Others resisted during the St. John River Campaign and the Petitcodiac River Campaign.[60]

Lawrencetown

By June 1757, the settlers had to be withdrawn completely from the settlement of Lawrencetown (established 1754) because the number of Indian raids eventually prevented settlers from leaving their houses.[61]

In near-by Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, in the spring of 1759, there was another Mi'kmaq attack on Fort Clarence (located at the present day Dartmouth Refinery), in which five soldiers were killed.[62]

Maine

In present-day Maine, the Mi’kmaq and the Maliseet raided numerous New England villages. At the end of April 1755, they raided Gorham, Maine, killing two men and a family. Next they appeared in New-Boston (Gray) and through the neighbouring towns destroying the plantations. On May 13, they raided Frankfort (Dresden), where two men were killed and a house burned. The same day they raided Sheepscot (Newcastle), and took five prisoners. Two were killed in North Yarmouth on May 29 and one taken captive. They shot one person at Teconnet. They took prisoners at Fort Halifax; two prisoners taken at Fort Shirley (Dresden). They took two captive at New Gloucester as they worked on the local fort.[63]

On 13 August 1758 Boishebert left Miramichi, New Brunswick with 400 soldiers, including Acadians which he led from Port Toulouse. They marched to Fort St George (Thomaston, Maine) and Munduncook (Friendship, Maine). While the former siege was unsuccessful, in the latter raid on Munduncook, they wounded eight British settlers and killed others. This was Boishébert’s last Acadian expedition. From there, Boishebert and the Acadians went to Quebec and fought in the Battle of Quebec (1759).[64]

Lunenburg

The Acadians and Mi'kmaq raided the Lunenburg settlement nine times over a three year period during the war. Boishebert ordered the first Raid on Lunenburg (1756). Following the raid of 1756, in 1757, there was a raid on Lunenburg in which six people from the Brissang family were killed.[65] The following year, March 1758, there was a raid on the Lunenburg Peninsula at the Northwest Range (present-day Blockhouse, Nova Scotia) when five people were killed from the Ochs and Roder families.[66] By the end of May 1758, most of those on the Lunenburg Peninsula abandoned their farms and retreated to the protection of the fortifications around the town of Lunenburg, losing the season for sowing their grain.[67] For those that did not leave their farms for the town, the number of raids intensified.

During the summer of 1758, there were four raids on the Lunenburg Peninsula. On 13 July 1758, one person on the LaHave River at Dayspring was killed and another seriously wounded by a member of the Labrador family.[68] The next raid happened at Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia on 24 August 1758, when eight Mi'kmaq attacked the family homes of Lay and Brant. While they killed three people in the raid, the Mi'kmaq were unsuccessful in taking their scalps, which was the common practice for payment from the French.[69] Two days, later, two soldiers were killed in a raid on the blockhouse at LaHave, Nova Scotia.[70] Almost two weeks later, on 11 September, a child was killed in a raid on the Northwest Range.[71] Another raid happened on 27 March 1759, in which three members of the Oxner family were killed.[65] The last raid happened on 20 April 1759. The Mi’kmaq killed four settlers at Lunenburg who were members of the Trippeau and Crighton families.[72]

Halifax

Acadian Pierre Gautier, son of Joseph-Nicolas Gautier, led Mi’kmaq warriors from Louisbourg on three raids against Halifax in 1757. In each raid, Gautier took prisoners or scalps or both. The last raid happened in September and Gautier went with four Mi’kmaq and killed and scalped two British men at the foot of Citadel Hill. (Pierre went on to participate in the Battle of Restigouche.) [73]

In July 1759, Mi'kmaq and Acadians kill five British in Dartmouth, opposite McNabb's Island.[74]

Bury the Hatchet Ceremony

The seventy-five year period of war ended with the Burial of the Hatchet Ceremony between the British and the Mi'kmaq (1761).

American Revolution

Until the outbreak of the American Revolution in 1775, Nova Scotia's New England-born merchants often sympathize with the rebels in the 13 colonies. But the Nova Scotia government was controlled by an Anglo-European mercantile elite for whom loyalty was more profitable than rebellion. The Yankees remained neutral during the war but experienced a religious revival that expressed some of their anxieties.[75]

Throughout the war, American privateers devastated the maritime economy by raiding many of the coastal communities. There were constant attacks by American privateers,[76] such as the Raid on Lunenburg (1782), numerous raids on Liverpool, Nova Scotia (October 1776, March 1777, September 1777, May 1778, September 1780) and a raid on Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia (1781).[77]

American Privateers also raided Canso, Nova Scotia (1775). In 1779, American privateers returned to Canso and destroyed the fisheries, which were worth £50,000 a year to Britain.[78]

To guard against such attacks, the 84th Regiment of Foot (Royal Highland Emigrants) was garrisoned at forts around the Atlantic Canada. Fort Edward (Nova Scotia) in Windsor, Nova Scotia was the Regiment's headquarters to prevent a possible American land assault on Halifax from the Bay of Fundy. There was an American attack on Nova Scotia by land, the Battle of Fort Cumberland followed by the Siege of Saint John (1777). There was also rebellion from those within Nova Scotia: the Maugerville Rebellion (1776) and the Battle at Miramichi (1779).

During the war, American Privateers captured 225 vessels either leaving or arriving at Nova Scotia ports.[79] In 1781, for example, as a result of the Franco-American alliance against Great Britain, there was also a naval engagement with a French fleet at Sydney, Nova Scotia, near Spanish River, Cape Breton.[80] The British also captured numerous American Privateers such as in the naval battle off Halifax. The Royal Navy also used Halifax as a base from which to launch attacks on New England, such as the Battle of Machias (1777). (Notably, Sir John Moore served at Halifax from 1779-1781.)

In 1784 the western, mainland portion of the colony was separated and became the province of New Brunswick, and the territory in Maine entered the control of the newly independent American state of Massachusetts. Cape Breton Island became a separate colony in 1784 only to be returned to Nova Scotia in 1820.

Nineteenth century

War of 1812

During the War of 1812, Nova Scotia’s contribution to the war effort was communities either purchasing or building various privateer ships to seize American vessels.[81] Three members of the community of Lunenburg, Nova Scotia purchased a privateer schooner and named it Lunenburg on August 8, 1814.[82] The Nova Scotian privateer vessel captured seven American vessels. The Liverpool Packet from Liverpool, Nova Scotia was another Nova Scotia privateer vessel that caught over fifty ships in the war - the most of any privateer in Canada.[83] The Sir John Sherbrooke (Halifax) was also very successful during the war, being the largest privateer on the Atlantic coast.

Perhaps the most dramatic moment in the war for Nova Scotia was the HMS Shannon's led the captured American Frigate USS Chesapeake into Halifax Harbour (1813). The Captain of the Shannon was injured and Nova Scotian Provo Wallis took command of the ship to escort the Chesapeake to Halifax. Many of the prisoners were kept at Deadman's Island, Halifax.[83] At the same time, there was the HMS Hogue's traumatic capture of the American Privateer Young Teazer off Chester, Nova Scotia.

On September 3, 1814 a British fleet from Halifax, Nova Scotia began to lay siege to Maine to re-establish British title to Maine east of the Penobscot River, an area the British had renamed "New Ireland". Carving off "New Ireland" from New England had been a goal of the British government and settlers of Nova Scotia ("New Scotland") since the American Revolution.[84] The British expedition involved 8 war-ships and 10 transports (carrying 3,500 British regulars) that were under the overall command of Sir John Coape Sherbrooke, then Lt. Gov. of Nova Scotia.[85] On July 3, 1814, the expedition captured the coastal town of Castine, Maine and then went on to raid Belfast, Machias, Eastport, Hampden and Bangor(See Battle of Hampden). After the war, Maine was returned to America through the Treaty of Ghent. The British returned to Halifax and, with the spoils of war they had taken from Maine, they built Dalhousie University (established 1818).[86]

The most famous soldier that was buried in Nova Scotia during the war was Robert Ross (British Army officer). Ross was responsible for the Burning of Washington, including the White House. (Other famous Nova Scotians who served in the war are:George Edward Watts, Sir George Augustus Westphal, Sir Edward Belcher, and Philip Westphal - all of whom are commeorated by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada plaques at Stadacona, CFB Halifax.)

Crimean War

Nova Scotians fought in the Crimean War. The Welsford-Parker Monument in Halifax is the oldest war monument in Canada and the only Crimean War monument in North America. Another Nova Scotian soldier who fought with distinction during the Crimean war was Sir William Williams, 1st Baronet, of Kars.

Indian Mutiny

Nova Scotians also participated in the Indian Muntiny. Two of the most famous were William Hall (VC) and Sir John Eardley Inglis, both of whom participated in the Siege of Lucknow.

-

Nova Scotian Sir John Eardley Inglis, Province House (Nova Scotia)

American Civil War

Over 200 Nova Scotians have been identified as fighting in the American Civil War (1861–1865). Most joined Maine or Massachusetts infantry regiments, but one in ten served the Confederacy (South). The total probably reached into two thousand as many young men had migrated to the U.S. before 1860. Pacifism, neutrality, anti-Americanism, and anti-Yankee sentiments all operated to keep the numbers down, but on the other hand there were strong cash incentives to join the well-paid Northern army and the long tradition of emigrating out of Nova Scotia, combined with a zest for adventure, attracted many young men.[87]

The British Empire (including Nova Scotia) declared neutrality, and Nova Scotia prospered greatly from trade with the North. There were no attempts to trade with the South. Nova Scotia was the site of two minor international incidents during the war: the Chesapeake Affair and the escape from Halifax Harbour of the CSS Tallahassee, aided by Confederate sympathizers.[88]

The war left many fearful that the North might attempt to annex British North America, particularly after the Fenian raids began. In response, volunteer regiments were raised across Nova Scotia. One of the main reasons why Britain sanctioned the creation of Canada (1867) was to avoid another possible conflict with America and to leave the defence of Nova Scotia to a Canadian Government.[89]

North West Rebellion

The Halifax Provisional Battalion was a military unit from Nova Scotia, Canada, which was sent to fight in the North-West Rebellion in 1885. The battalion was under command of Lieut.-Colonel James J. Bremner and consisted of 168 non-commissioned officers and men of the The Princess Louise Fusiliers, 100 of the 63rd Battalion Rifles, and 84 of the Halifax Garrison Artillery, with 32 officers. The battalion left Halifax under orders for the North-West on Saturday, April 11, 1885, and they stayed for almost three months.[90]

Twentieth century

Second Boer War

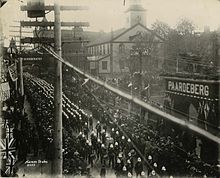

During the Second Boer War (1899–1902), the First Contingent was composed of seven Companies from across Canada. The Nova Scotia Company (H) consisted of 125 men. (The total First Contingent was a total force of 1,019. Eventually over 8600 Canadians served.) The mobilization of the Contingent took place at Quebec. On October 30, 1899, the ship Sardinian sailed the troops for four weeks to Cape Town. The Boer War marked the first occasion in which large contingents of Nova Scotian troops served abroad (individual Nova Scotians had served in the Crimean War). The Battle of Paardeberg in February 1900 represented the second time Canadian soldiers saw battle abroad (the first being the Canadian involvement in the Nile Expedition).[91] Canadians also saw action at the Battle of Faber's Put on May 30, 1900.[92] On November 7, 1900, the Royal Canadian Dragoons engaged the Boers in the Battle of Leliefontein, where they saved British guns from capture during a retreat from the banks of the Komati River.[93] Approximately 267 Canadians died in the War. 89 men were killed in action, 135 died of disease, and the remainder died of accident or injury. 252 were wounded.

Of all the Canadians who died during the war, the most famous was the young Lt. Harold Lothrop Borden of Canning, Nova Scotia. Harold Borden's father was Sir Frederick W. Borden, Canada's Minister of Militia who was a strong proponent of Canadian participation in the war.[94] Another famous Nova Scotian casualty of the war was Charles Carroll Wood, son of the renoun Confederate naval captain John Taylor Wood and the first Canadian to die in the war.[95]

First World War

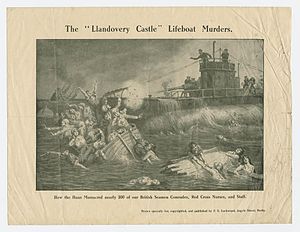

During World War I, Halifax became a major international port and naval facility. The harbour became a major shipment point for war supplies, troop ships to Europe from Canada and the United States and hospital ships returning the wounded. These factors drove a major military, industrial and residential expansion of the city.[96] On 27 June 1917, a German U-boat torpedoed a hospital ship from the port of Halifax named the HMHS Llandovery Castle. Escaping lifeboats were pursued and sunk by the German U-boat and the survivors machine-gunned. Of the crew totalling 258, only twenty-four survived.[97]

On Thursday, December 6, 1917, when the city of Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, was devastated by the huge detonation of a French cargo ship, fully loaded with wartime explosives, that had accidentally collided with a Norwegian ship in "The Narrows" section of the Halifax Harbour. Approximately 2,000 people (mostly Canadians) were killed by debris, fires, or collapsed buildings, and it is estimated that over 9,000 people were injured.[98] This is still the world's largest man-made accidental explosion.[99]

World War II

During World War II,thousands of Nova Scotians went overseas. One Nova Scotian, Mona Louise Parsons, joined the Dutch resistance and was eventually captured and imprisoned by the Nazis for almost four years.

Notable Nova Scotian Military Figures

17-18 Century

-

Grave of Sébastien Rale

-

Chief Jean-Baptiste Cope

-

Father Jean-Louis Le Loutre

-

Acadian Joseph Broussard

19th Century

-

Nova Scotian Sir William Williams, 1st Baronet, of Kars by William Gush

-

Nova Scotian Sir John Eardley Inglis by William Gush

Also See

- Chief Madockawando

External Links

Also See

References

- ^ a b William Williamson. The history of the state of Maine. Vol. 2. 1832. p. 27

- ^ In 1765, the county of Sunbury was created, and included the territory of present-day New Brunswick and eastern Maine as far as the Penobscot River.

- ^ Also, that same year, French fishermen established a settlement at Canso.

- ^ Brenda Dunn. A History of Port Royal, Annapolis Royal: 1605-1800. Nimbus Publishing, 2004

- ^ Nicholls, Andrew. A Fleeting Empire: Early Stuart Britain and the Merchant Adventures to Canada. McGill-Queen's University Press. 2010.

- ^ M. A. MacDonald, Fortune & La Tour: The civil war in Acadia, Toronto: Methuen. 1983

- ^ Brenda Dunn, p. 19

- ^ Brenda Dunn. A History of Port Royal, Annapolis Royal: 1605-1800. Nimbus Publishing, 2004. p. 20

- ^ http://www.wabanaki.com/Harald_Prins.htm

- ^ Grenier, p. 56

- ^ Beamish Murdoch. History of Nova Scotia or Acadia, p. 399

- ^ A history of Nova-Scotia, or Acadie, Volume 1, by Beamish Murdoch, p. 398

- ^ The Nova Scotia theatre of the Dummer War is named the "Mi'kmaq-Maliseet War" by John Grenier. The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia 1710-1760. University of Oklahoma Press. 2008.

- ^ Beamish Murdoch. A history of Nova-Scotia, or Acadie, Volume 1, p. 399; Geoffery Plank, An Unsettled Conquest, p. 78

- ^ Benjamin Church, p. 289; John Grenier, p. 62

- ^ Faragher, John Mack, A Great and Noble Scheme New York; W. W. Norton & Company, 2005. pp. 164-165; Brenda Dunn, p. 123

- ^ William Wicken. Mi'kmaq Treaties on Trial. 2002. pp. 72-72.

- ^ The framework Father Le Loutre's War is developed by John Grenier in his books The Far Reaches of Empire. War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. (University of Oklahoma Press, 2008) and The first way of war: American war making on the frontier, 1607-1814 (Cambridge University Press, 2005). He outlines his rational for naming these conflicts as Father Le Loutre's War; Thomas Beamish Akins. History of Halifax, Brookhouse Press. 1895. (2002 edition). p 7

- ^ Wicken, p. 181; Griffith, p. 390; Also see http://www.northeastarch.com/vieux_logis.html

- ^ a b John Grenier. The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. Oklahoma University Press.

- ^ John Grenier, Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia 1710-1760. Oklahoma Press. 2008

- ^ Stephen E. Patterson. "Indian-White Relations in Nova Scotia, 1749-61: A Study in Political Interaction." Buckner, P, Campbell, G. and Frank, D. (eds). The Acadiensis Reader Vol 1: Atlantic Canada Before Confederation. 1998. pp.105-106.; Also see Stephen Patterson, Colonial Wars and Aboriginal Peoples, p. 144.

- ^ Ronnie-Gilles LeBlanc (2005). Du Grand Dérangement à la Déportation: Nouvelles Perspectives Historiques, Moncton: Université de Moncton, 465 pages ISBN 1-897214-02-2 (book in French and English). The Acadians were scattered across the Atlantic, in the Thirteen Colonies, Louisiana, Quebec, Britain and France. (See Jean-François Mouhot (2009) Les Réfugiés acadiens en France (1758-1785): L'Impossible Réintégration?, Quebec, Septentrion, 456 p. ISBN 2-89448-513-1; Ernest Martin (1936) Les Exilés Acadiens en France et leur établissement dans le Poitou, Paris, Hachette, 1936). Very few eventually returned to Nova Scotia (See John Mack Faragher (2005). A Great and Noble Scheme: The Tragic Story of the Expulsion of the French Acadians from their American Homeland, New York: W.W. Norton, 562 pages ISBN 0-393-05135-8 online excerpt).

- ^ Faragher, John Mack (2005-02-22). A great and noble scheme: the tragic story of the expulsion of the French Acadians from their American Homeland. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 338. ISBN 978-0-393-05135-3.

- ^ a b John Grenier. The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. Oklahoma University Press. 2008

- ^ John Grenier, p. 184

- ^ Winthrop Bell. Foreign Protestants, University of Toronto, 1961, p. 504; Peter Landry. The Lion and the Lily, Trafford Press. 2007.p. 555

- ^ John Grenier, The Far Reaches of Empire, Oklahoma Press. 2008. p. 198

- ^ Marshall, p. 98; see also Bell. Foreign Protestants. p. 512

- ^ Marshall, p. 98; Peter Landry. The Lion and the Lily, Trafford Press. 2007. p. 555

- ^ Earle Lockerby, The Expulsion of the Acadians from Prince Edward Island. Nimbus Publications. 2009

- ^ Plank, p. 160

- ^ John Grenier, p. 197

- ^ Grenier, p. 198; Faragher, p. 402.

- ^ Grenier, p. 198

- ^ John Grenier. The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760, Oklahoma University Press.pp. 199-200. Note that John Faragher in the Great and Nobel Scheme indicates that Monckton had a force of 2000 men for this campaign. p. 405.

- ^ a b John Grenier. The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760, Oklahoma University Press. 2008, pp. 199-200

- ^ a b John Grenier. The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. Oklahoma University Press, p. 202; Also see Plank, p. 61

- ^ A letter from Fort Frederick which was printed in Parker’s New York Gazette or Weekly Post-Boy on 2 April 1759 provides some additional details of the behavior of the Rangers. Also see William O. Raymond. The River St. John: Its Physical Features, Legends and History from 1604 to 1784. St. John, New Brunswick. 1910. pp. 96-107

- ^ J.S. McLennan, Louisbourg: From its Founding to its Fall, Macmillan and Co. Ltd London, UK 1918, pp. 417-423, Appendix 11 (see http://www.archive.org/stream/louisbourgfromit00mcleuoft/louisbourgfromit00mcleuoft_djvu.txt)

- ^ Lockerby, 2008, p.17, p.24, p.26, p.56

- ^ Faragher, p. 414; also see History: Commodore Byron's Conquest. The Canadian Press. July 19, 2008 http://www.acadian.org/La%20Petite-Rochelle.html

- ^ John Grenier, p. 211; John Faragher, p. 41; see the account of Captain Mackenzie's raid at MacKenzie's Raid

- ^ Patterson, 1994, p. 153; Brenda Dunn, p. 207

- ^ Griffith, 2005, p. 438

- ^ Faragher, p. 423–424

- ^ John Gorham. The Far Reaches of Empire: War In Nova Scotia (1710-1760). University of Oklahoma Press. 2008. p. 177-206

- ^ Patterson, Stephen E. 1744-1763: Colonial Wars and Aboriginal Peoples. In Phillip Buckner and John Reid (eds.) The Atlantic Region to Conderation: A History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. 1994. p. 148

- ^ Faragher, John Mack 2005. pp. 110

- ^ The journal of John Weatherspoon was published in Collections of the Nova Scotia Historical Society for the Years 1879-1880 (Halifax 1881) that has since been reprinted (Mika Publishing Company, Belleville, Ontario, 1976).

- ^ Winthrop Bell, Foreign Protestants, University of Toronto. 1961. p.503

- ^ John Faragher. Great and Noble Scheme. Norton. 2005. p. 398.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Faragher, John Mack 2005. pp. 110was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Webster as cited by bluepete, p. 371

- ^ John Faragher.Great and Noble Scheme. Norton. 2005. p. 398.

- ^ John Grenier, p. 190; New Brunswick Military Project

- ^ John Grenier, p. 195

- ^ John Faragher, p. 410

- ^ New Brunswick Military Project

- ^ John Grenier. The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760, Oklahoma University Press.pp. 199–200

- ^ Bell Foreign Protestants. p. 508

- ^ Harry Chapman, p. 32; John Faragher, p. 410

- ^ William Williamson. The history of the state of Maine. Vol. 2. 1832. p. 311-112; During this time period, the Maliseet and Mi'kmaq were the only tribes of the Wabanaki Confederacy who were able to right.

- ^ Phyllis E. Leblanc, Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online; Cyrus Eaton's history, p. 77; William Durkee Williamson, The history of the state of Maine: from its first discovery, A. D ..., Volume 2, p. 333 (Williamson's Book)

- ^ a b Archibald McMechan, Red Snow of Grand Pre. 1931. p. 192

- ^ Bell, p. 509

- ^ Bell. Foreign Protestants. p. 510, p. 513

- ^ Bell, p. 510

- ^ Bell, Foreign Protestants, p. 511

- ^ Bell, p. 511

- ^ Bell, p. 512

- ^ Bell, p. 513

- ^ Earle Lockerby. Pre-Deportation Letters from Ile Saint Jean. Les Cahiers. La Societe hitorique acadienne. Vol. 42, No2. June 2011. pp. 99-100

- ^ Beamish Murdoch. History of Nova Scotia. Vol.2. p. 366

- ^ Barry Cahill, "The Treason of the Merchants: Dissent and Repression in Halifax in the Era of the American Revolution," Acadiensis 1996 26(1): 52-70; G. Stewart, and G. Rawlyk, A People Highly Favoured of God: The Nova Scotia Yankees and the American Revolution (1972); Maurice Armstrong, "Neutrality and Religion in Revolutionary Nova Scotia," The New England Quarterly v19, no. 1 (1946): 50-62 in JSTOR

- ^ Benjamin Franklin also engaged France in the war, which meant that many of the privateers were also from France.

- ^ Roger Marsters (2004). Bold Privateers: Terror, Plunder and Profit on Canada's Atlantic Coast" , p. 87-89.

- ^ Lieutenant Governor Sir Richard Hughes stated in a dispatch to Lord Germaine that "rebel cruisers" made the attack.

- ^ Julian Gwyn. Frigates and Foremasts. University of British Columbia. 2003. p. 56

- ^ Thomas B. Akins. (1895) History of Halifax. Dartmouth: Brook House Press.p. 82

- ^ John Boileau. Half-hearted Enemies: Nova Scotia, New England and the War of 1812. Halifax: Formac Publishing. 2005. p.53

- ^ C.H.J.Snider, Under the Red Jack: privateers of the Maritime Provinces of Canada in the War of 1812 (London: Martin Hopkinson & Co. Ltd, 1928), 225-258 (see http://www.1812privateers.org/Ca/canada.htm#LG)

- ^ a b John Boileau. 2005. Half-hearted Enemies: Nova Scotia: New England and the War of 1812. Formac Press

- ^ Seymour, p. 10

- ^ Tom Seymour, Tom Seymour's Maine: A Maine Anthology (2003), pp. 10-17

- ^ D.C. Harvey, "The Halifax–Castine expedition," Dalhousie Review, 18 (1938–39): 207–13.

- ^ Greg Marquis, "Mercenaries or Killer Angels? Nova Scotians in the American Civil War," Collections of the Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society, 1995, Vol. 44, pp 83-94

- ^ Greg Marquis, In Armageddon’s Shadow: The Civil War and Canada’s Maritime Provinces . McGill-Queen’s University Press. 1998.

- ^ Marquis, In Armageddon’s Shadow

- ^ The history of the North-west rebellion of 1885: Comprising a full and ... By Charles Pelham Mulvany, Louis Riel, p. 410

- ^ Canadian War Museum (2008). "Battle of Paardeberg". Canadian War Museum. Retrieved 2008-05-10. [dead link]

- ^ Canadian War Museum (2008). "Battle of Faber's Put". Canadian War Museum. Retrieved 2008-05-10. [dead link]

- ^ Canadian War Museum (2008). "Battle of Leliefontein". Canadian War Museum. Retrieved 2008-05-10. [dead link]

- ^ http://angloboerwarmuseum.com/Boer70g_hero7_borden1.html

- ^ John Bell. Confederate Seadog: John Taylor Wood in War and Exile. McFarland Publishers. 2002. p. 59

- ^ The Halifax Explosion and the Royal Canadian Navy John Armstrong, University of British Columbia Press, 2002, p.10-11.

- ^ http://pw20c.mcmaster.ca/case-study/angels-mercy-canada-s-nursing-sisters-world-war-i-and-ii

- ^ CBC - Halifax Explosion 1917

- ^ Jay White, "Exploding Myths: The Halifax Explosion in Historical Context", Ground Zero: A Reassessment of the 1917 explosion in Halifax Alan Ruffman and Colin D. Howell editors, Nimbus Publishing (1994), p. 266

Bibliography

- Douglas, W. A. B. The Sea Militia of Nova Scotia, 1749-1755: A Comment on Naval Policy. The Canadian Historical Review. Vol. XLVII, No.1. 1966. 22-37

- Joseph Plimsoll Edwards. The Militia of Nova Scotia, 1749-1867. Collections of the Nova Scotia Historical Society. Vol. 17 (1913). pp. 63–110.

- Faragher, John Mack, A Great and Noble Scheme New York; W. W. Norton & Company, 2005. pp. 110–112 ISBN 0-393-05135-8

- Grenier, John. The Far Reaches of Empire. War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. Norman: U of Oklahoma P, 2008. pp. 154–155

- Griffiths, Naomi Elizabeth Saundaus. From Migrant to Acadian: A North American border people, 1604-1755. Montreal, Kingston: McGill-Queen's UP, 2005.

- Landry, Peter. The Lion & The Lily. Vol. 1. Victoria: Trafford, 2007.

- Murdoch, Beamish. A History of Nova Scotia, Or Acadia. Vol 2. LaVergne: BiblioBazaar, 2009. pp. 166–167

- Patterson, Stephen E. 1744-1763: Colonial Wars and Aboriginal Peoples. In Phillip Buckner and John Reid (eds.) The Atlantic Region to Conderation: A History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. 1994. pp. 125–155

- Patterson, Stephen E. "Indian-White Relations in Nova Scotia, 1749-61: A Study in Political Interaction." Buckner, P, Campbell, G. and Frank, D. (eds). The Acadiensis Reader Vol 1: Atlantic Canada Before Confederation. 1998. pp. 105–106.

- Rompkey, Ronald, ed. Expeditions of Honour: The Journal of John Salusbury in Halifax, Nova Scotia, 1749-53. Newark: U of Delaware P, Newark, 1982.

- John Clarence Webster. The career of the Abbé Le Loutre in Nova Scotia (Shediac, N.B., 1933),

- Wicken, William. Mi'kmaq Treaties on Trial: History, Land, and Donald Marshall Junior. University of Toronto Press. 2002.

- Brenda Dunn, A History of Port-Royal/Annapolis Royal 1605-1800, Halifax: Nimbus, 2004 ISBN 1-55109-740-0

- Griffiths, E. From Migrant to Acadian. McGill-Queen's University Press. 2005 ISBN 0-7735-2699-4

- John Grenier. The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. Oklahoma University Press. 2008 ISBN 978-0-8061-3876-3

- John G. Reid. The 'Conquest' of Acadia, 1710: Imperial, Colonial, an Aboriginal Constructions University of Toronto Press. 2004 ISBN 0-8020-3755-0

- Geoffrey Plank, An Unsettled Conquest. University of Pennsylvania. 2001 ISBN 0-8122-1869-8

- Faragher, John Mack (2005). A Great and Noble Scheme: The Tragic Story of the Expulsion of the French Acadians from their American Homeland, New York: W.W. Norton, 562 pages ISBN 0-393-05135-8

- Johnston, John. The Acadian Deportation in a Comparative Context: An Introduction. Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society: The Journal. 2007. pp. 114–131

- Moody, Barry (1981). The Acadians, Toronto: Grolier. 96 pages ISBN 0-7172-1810-4

- *Patterson, Stephen E. 1744-1763: Colonial Wars and Aboriginal Peoples. In Phillip Buckner and John Reid (eds.) The Atlantic Region to Conderation: A History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. 1994. pp. 125–155

- Griffiths, N.E.S. (1969). The Acadian deportation: deliberate perfidy or cruel necessity?, Toronto: Copp Clark Pub. Co., 165 p.

- Doughty, Arthur G. (1916). The Acadian Exiles. A Chronicle of the Land of Evangeline, Toronto: Glasgow, Brook & Co. 178 pages

- Government of Nova Scotia transcripts from Journal of John Winslow

- Text of Charles Lawrence's orders to Captain John Handfield - Halifax 11 August 1755