Spanish colonization of the Americas: Difference between revisions

Shouldn't remove this whole section although the last half of it is straying off topic |

Reorganized into two sections "Demographic impact" and "Cultural impact" |

||

| Line 74: | Line 74: | ||

In 1898, the [[United States]] won victory in the [[Spanish-American War]] from Spain, ending the colonial era. Spanish possession and rule of its remaining colonies in the Americas ended in that year with its ownership transfer to the United States. The U.S. took occupation of [[Cuba]], the [[Philippines]], and [[Puerto Rico]]. The latter possession now officially continues as a [[self-governing]] [[unincorporated territory]] of the United States. |

In 1898, the [[United States]] won victory in the [[Spanish-American War]] from Spain, ending the colonial era. Spanish possession and rule of its remaining colonies in the Americas ended in that year with its ownership transfer to the United States. The U.S. took occupation of [[Cuba]], the [[Philippines]], and [[Puerto Rico]]. The latter possession now officially continues as a [[self-governing]] [[unincorporated territory]] of the United States. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

===Indigenous peoples (Native Americans)=== |

|||

{{Main|Indigenous peoples of the Americas|Native Americans in the United States}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

The cultures and populations of the [[Classification of indigenous peoples of the Americas|indigenous peoples of the Americas]] were changed by the Spanish assumption and colonization of their lands. |

|||

| ⚫ | It has been estimated that in the 16th century about 240,000 Spaniards emigrated to America, and in the 17th century about 500,000, predominantly to [[Mexico]] and [[Peru]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.let.leidenuniv.nl/history/migration/chapter53.html |title=Migration to Latin America |publisher=Let.leidenuniv.nl |date= |accessdate=2011-09-04}}</ref> |

||

Before the arrival of Columbus, in Hispaniola the indigenous Taíno pre-contact population of several hundred thousand declined to sixty thousand by 1509. Although population estimates vary, Father [[Bartolomé de las Casas]], the “Defender of the Indians” estimated there were 6 million (6,000,000) [[Taíno people|Taíno]] and [[Arawak peoples|Arawak]] in the Caribbean at the time of Columbus's arrival in 1492.{{Citation needed|date=April 2010}} |

Before the arrival of Columbus, in Hispaniola the indigenous Taíno pre-contact population of several hundred thousand declined to sixty thousand by 1509. Although population estimates vary, Father [[Bartolomé de las Casas]], the “Defender of the Indians” estimated there were 6 million (6,000,000) [[Taíno people|Taíno]] and [[Arawak peoples|Arawak]] in the Caribbean at the time of Columbus's arrival in 1492.{{Citation needed|date=April 2010}} |

||

| Line 86: | Line 85: | ||

Of the history of the indigenous population of [[California]], [[Sherburne F. Cook]] (1896–1974) was the most painstakingly careful researcher. From decades of research he made estimates for the pre-contact population and the history of demographic decline during the Spanish and post-Spanish periods. According to Cook, the indigenous Californian population at first contact, in 1769, was about 310,000 and had dropped to 25,000 by 1910. The vast majority of the decline happened after the Spanish period, in the [[Mexico|Mexican]] and [[U.S.A|U.S.]] periods of Californian history (1821–1910), with the most dramatic collapse (200,000 to 25,000) occurring in the U.S. period (1846–1910).<ref>Baumhoff, Martin A. 1963. ''Ecological Determinants of Aboriginal California Populations.'' ''University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology'' 49:155-236.</ref><ref>Powers, Stephen. 1875. "California Indian Characteristics". ''Overland Monthly'' 14:297-309. [http://www.hti.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/pageviewer-idx?c=moajrnl&cc=moajrnl&idno=ahj1472.1-14.004&node=ahj1472.1-14.004%3A1&frm=frameset&view=image&seq=293 on-line]</ref><ref>Cook's judgement on the effects of U.S rule upon the native Californians is harsh: "The first (factor) was the food supply... The second factor was disease. ...A third factor, which strongly intensified the effect of the other two, was the social and physical disruption visited upon the Indian. He was driven from his home by the thousands, starved, beaten, raped, and murdered with impunity. He was not only given no assistance in the struggle against foreign diseases, but was prevented from adopting even the most elementary measures to secure his food, clothing, and shelter. The utter devastation caused by the white man was literally incredible, and not until the population figures are examined does the extent of the havoc become evident."Cook, Sherburne F. 1976b. ''The Population of the California Indians, 1769-1970''. University of California Press, Berkeley|p. 200</ref> |

Of the history of the indigenous population of [[California]], [[Sherburne F. Cook]] (1896–1974) was the most painstakingly careful researcher. From decades of research he made estimates for the pre-contact population and the history of demographic decline during the Spanish and post-Spanish periods. According to Cook, the indigenous Californian population at first contact, in 1769, was about 310,000 and had dropped to 25,000 by 1910. The vast majority of the decline happened after the Spanish period, in the [[Mexico|Mexican]] and [[U.S.A|U.S.]] periods of Californian history (1821–1910), with the most dramatic collapse (200,000 to 25,000) occurring in the U.S. period (1846–1910).<ref>Baumhoff, Martin A. 1963. ''Ecological Determinants of Aboriginal California Populations.'' ''University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology'' 49:155-236.</ref><ref>Powers, Stephen. 1875. "California Indian Characteristics". ''Overland Monthly'' 14:297-309. [http://www.hti.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/pageviewer-idx?c=moajrnl&cc=moajrnl&idno=ahj1472.1-14.004&node=ahj1472.1-14.004%3A1&frm=frameset&view=image&seq=293 on-line]</ref><ref>Cook's judgement on the effects of U.S rule upon the native Californians is harsh: "The first (factor) was the food supply... The second factor was disease. ...A third factor, which strongly intensified the effect of the other two, was the social and physical disruption visited upon the Indian. He was driven from his home by the thousands, starved, beaten, raped, and murdered with impunity. He was not only given no assistance in the struggle against foreign diseases, but was prevented from adopting even the most elementary measures to secure his food, clothing, and shelter. The utter devastation caused by the white man was literally incredible, and not until the population figures are examined does the extent of the havoc become evident."Cook, Sherburne F. 1976b. ''The Population of the California Indians, 1769-1970''. University of California Press, Berkeley|p. 200</ref> |

||

== |

==Cultural impact== |

||

{{main|Spanish missions in the Americas}} |

{{main|Spanish missions in the Americas}} |

||

| Line 92: | Line 91: | ||

Though the Spanish did not impose their language to the extent they did their religion, some [[indigenous languages of the Americas]] evolved into replacement with Spanish, and lost to present day tribal members. When more efficient they did evangelize in native languages. Introduced writing systems to the Quechua, Nahuatl and Guarani peoples may have contributed to their expansion.{{Citation needed|date=April 2010}} |

Though the Spanish did not impose their language to the extent they did their religion, some [[indigenous languages of the Americas]] evolved into replacement with Spanish, and lost to present day tribal members. When more efficient they did evangelize in native languages. Introduced writing systems to the Quechua, Nahuatl and Guarani peoples may have contributed to their expansion.{{Citation needed|date=April 2010}} |

||

===Spanish emigration=== |

|||

{{off topic}} |

|||

| ⚫ | It has been estimated that in the 16th century about 240,000 Spaniards emigrated to America, and in the 17th century about 500,000, predominantly to [[Mexico]] and [[Peru]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.let.leidenuniv.nl/history/migration/chapter53.html |title=Migration to Latin America |publisher=Let.leidenuniv.nl |date= |accessdate=2011-09-04}}</ref> |

||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 13:50, 28 September 2011

Red: Farthest extent of Spanish colonies under the House of Bourbon in the 1790s.

Pink: Disputed claims of Spanish colonial administration.

Purple: Portuguese colonies under dual Spanish colonial administration during 1580-1640.

The Spanish Colonization of America was the exploration, conquest, settlement and political rule over much of the Western Hemisphere Spanish Empire. It was initiated by the Spanish conquistadores and developed by the Monarchy of Spain through its administrators and missionaries. The motivations for colonial expansion were trade and the spread of the Christian faith through indigenous conversions. It lasted for over four hundred years, from 1492 to 1898.

Beginning with the 1492 arrival of Christopher Columbus, over nearly four centuries the Spanish Empire would expand across: most of present day Central America, the Caribbean islands, and Mexico; much of the rest of North America including the Southwestern, Southern coastal, and California Pacific Coast regions of the United States; and though inactive, with claimed territory in present day British Columbia Canada; and U.S. states of Alaska, Washington, and Oregon; and the western half of South America.[1][2][3] In the early 19th century the revolutionary movements resulted in the independence of most Spanish colonies in America, except for Cuba and Puerto Rico, given up in 1898 following the Spanish-American War, together with Guam and the Philippines in the Pacific. Spain's loss of these last territories politically ended Spanish colonization in America. The cultural influences, though, still remain.

Exploration

| Part of a series on |

| European colonization of the Americas |

|---|

|

|

|

Christopher Columbus

Since the early 15th century, Portuguese explorers sailing caravels established new southward routes along the coast of West Africa. In 1488 they rounded the Cape of Good Hope and explored parts of East Africa. They discovered rich trading regions in the Indonesian continent and established several trading ports along the West Indonesia coast, and later India.

In 1485 Christopher Columbus unsuccessfully tried to persuade King John II of Portugal (João II) to sponsor an expedition to Asia by sailing west across the Atlantic Ocean. This alternative route, different from the theoretical eastward route, was based on the conviction that the earth was round. His proposal was rejected by the Portuguese, who thought the distance to Asia was much greater than Columbus had assured. In 1488 again he presented his plan to the Portuguese King, who refused based on the recent discovery by Bartholomeu Dias of the eastward route along the African coast and across the Indian Ocean.

Columbus was more persuasive with the Catholic Monarchs of Spain: recently crowned Isabella I Queen of Castile and her husband Ferdinand II King of Aragon. Although he presented his plan as early as 1486, his arguments for reaching Asian trade centers by sailing West across the Atlantic Ocean did not convince the Spanish Monarchs until 1491. Queen Isabella played a decisive role in the decision of supporting Colombus' plans.

Finally, in August 1492 Colombus sailed from the Andalusian port of Palos de la Frontera in Southern Spain. Columbus arrived on the island of Guanahani in the Bahamas on October 12, 1492. On this first voyage, Columbus and his sailors were greeted by the Arawak people of the Bahamas. They were kind and curious people who brought them food, water and gifts. Columbus later wrote in his log: ....They would make fine servants.... With fifty men we could subjugate them all and make them do whatever we want. In the year of 1495, Columbus and his sailors rounded up fifteen hundred Arawak men, women and children. Out of those fifteen hundred, they picked five hundred of the best specimens and out of those five hundred, two hundred died en route.[4] He presented the Spanish monarchs with small items of gold, parrots, and other 'exotic' things. They commissioned Columbus for a second voyage, providing him with seventeen ships, nearly 1,500 men, cannons, crossbows, guns, cavalry, and attack dogs. He returned to claim the island of Hispaniola, present day Haiti and the Dominican Republic, from the indigenous Taíno people in 1493.[citation needed]

Columbus was granted governorship of the new territories and made more journeys across the Atlantic Ocean. While generally regarded as an excellent navigator, during this first stay in the New World, Columbus wrecked his flagship, the Santa Maria. He was a poor administrator and was stripped of the governorship in 1500, and in fact was jailed for six weeks once he returned to Spain. Spain then agreed to fund a fourth voyage, but Columbus could not be governor again.[citation needed]

He profited by using the labour of native slaves for agriculture and to mine gold. He attempted to sell native people as slaves in Spain, bringing five hundred people back.[citation needed] The Taínos began to resist the Spanish, refusing to plant and abandoning captured native villages. Over time the rebellion grew violent. In the resulting conflict, the native inhabitants used their extensive knowledge of the terrain and applied guerilla tactics such as booby traps, ambushes, attrition, and forced marches to tire the Spanish columns. Although stone arrows couldn't penetrate the best of the Spanish armor, they were somewhat effective if they were used as shrapnel, since they tended to shatter on impact; stone and copper or bronze maces were used more effectively. However, the most crucial weapon the native Americans used was the sling, which could hurl massive stones that easily crushed even the most heavily armoured caballero.[5]

In 1522, a Taíno Cacique named Enriquillo waged a successful rebellion causing the Spaniards to sign a treaty granting the Indian population the rights of Freedom and of Possession. It had little consequence however, as by then the Taíno population was rapidly declining due to European diseases, forced labour, and ritual suicides.[citation needed] The Taíno often refused to participate in activities forced upon them by the Spanish which resulted in suicide. Their children were killed as a perceived escape from a terrible future.[citation needed]

On his fourth and final voyage to America in 1502, Columbus encountered a large canoe off the coast of what is now Honduras filled with trade goods. He boarded the canoe and found cacao beans, copper and flint axes, copper bells, pottery, and colorful cotton garments. This was the first contact of the Spanish with the civilizations of Central America.[citation needed]

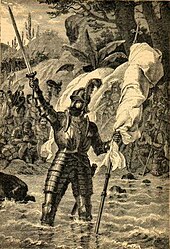

First mainland explorations

In 1513, Vasco Núñez de Balboa crossed the Isthmus of Panama, to find gold but instead led the first European expedition to the Pacific Ocean and the west coast of the New World. In an action with enduring historical import, Balboa claimed the Pacific Ocean and all the lands adjoining it for the Spanish Crown. It was 1517 before another expedition from Cuba explored Central America. It landed on the coast of the Yucatán peninsula in search of slaves.

Conquests

First settlements in America

The first mainland explorations were followed by a phase of inland expeditions and conquest. The Spanish crown extended the Reconquista effort, completed in Spain in 1492, to non-Catholic people in new territories. In 1502 on the coast of present day Colombia, near the Gulf of Urabá, Spanish explorers led by Vasco Núñez de Balboa explored and conquered the area near the Atrato River. The conquest was of the Chibchan speaking nations, mainly the Muisca and Tairona indigenous people that lived here. The Spanish founded San Sebastian de Uraba in 1509—abandoned within the year, and in 1510 the first permanent Spanish mainland settlement in America, Santa María la Antigua del Darién. [6] These were the first European settlements in America. The conquistadors were truly amazed by what they found — immense wealth in gold and silver, complex cities rivaling or surpassing those in Europe, and remarkable artistic and scientific achievements. Spanish conquest in the New World was driven by the three 'G's—God, glory, and gold. [7][8][9]

Mexico

There is a difference in the 'Spanish conquest of Mexico' between the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire and the Spanish conquest of Yucatán. The former is conquest of the campaign, led by Hernán Cortés from 1519–21 and his Tlaxcala and other 'indigenous peoples' allied against the Mexica/Aztec empire. The Spanish conquest of Yucatán is the much longer campaign, from 1551–1697, against the Maya peoples of the Maya civilization in the Yucatán Peninsula of present day Mexico and northern Central America. The day Hernán Cortés landed ashore at present day Veracruz, April 22, 1519, marks the beginning of 300 years of Spanish hegemony over the region.

Peru

In 1532 at the Battle of Cajamarca a group of Spanish soldiers under Francisco Pizarro and their indigenous Andean Indian auxiliaries native allies ambushed and captured the Emperor Atahualpa of the Inca Empire. It was the first step in a long campaign that took decades of fighting to subdue the mightiest empire in the Americas. In the following years Spain extended its rule over the Empire of the Inca civilization.

The Spanish took advantage of a recent civil war between the factions of the two brothers Emperor Atahualpa and Huáscar, and the enmity of indigenous nations the Incas had subjugated, such as the Huancas, Chachapoyas, and Cañaris. In the following years the conquistadors and indigenous allies extended control over the greater Andes region. The Viceroyalty of Perú was established in 1542.

Governing

Spain's administration of its colonies in the Americas was divided into the Viceroyalty of New Spain 1535 (capital, México City), and the Viceroyalty of Peru 1542 (capital, Lima). In the 18th century the additional Viceroyalty of New Granada 1717 (capital, Bogotá), and Viceroyalty of Rio de la Plata 1776 (capital, Buenos Aires) were established from portions of the Viceroyalty of Peru.

This evolved from the Council of the Indies and Viceroyalties into an Intendant system, in an attempt for more revenue and efficiency.

19th century

During the Peninsular War in Europe between France and Spain, assemblies called juntas were established to rule in the name of Ferdinand VII of Spain. The Libertadores (Spanish and Portuguese for "Liberators") were the principal leaders of the Latin American wars of independence from Spain. They were predominantly criollos (local-born people of European, mostly of Spanish or Portuguese, ancestry), bourgeois and influenced by liberalism and in most cases with military training in the mother country.

In 1809 the first declarations of independence from Spanish rule occurred in the Viceroyalty of New Granada. The first two were in present day Bolivia at Sucre (May 25), and La Paz ( July 16); and the third in present day Ecuador at Quito (August 10). In 1810 Mexico declared independence, with the Mexican War of Independence following for over a decade. In 1821 Treaty of Córdoba established Mexican independence from Spain and concluded the War. The Plan of Iguala was part of the peace treaty to establish a constitutional foundation for an independent Mexico.

These began a movement for colonial independence that spread to Spain's other colonies in the Americas. The ideas from the French and the American Revolution influenced the efforts. All of the colonies, except Cuba and Puerto Rico, attained independence by the 1820s. The British Empire offered support, wanting to end the Spanish monopoly on trade with its colonies in the Americas.

In 1898, the United States won victory in the Spanish-American War from Spain, ending the colonial era. Spanish possession and rule of its remaining colonies in the Americas ended in that year with its ownership transfer to the United States. The U.S. took occupation of Cuba, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico. The latter possession now officially continues as a self-governing unincorporated territory of the United States.

Demographic impact

It has been estimated that in the 16th century about 240,000 Spaniards emigrated to America, and in the 17th century about 500,000, predominantly to Mexico and Peru.[10]

Before the arrival of Columbus, in Hispaniola the indigenous Taíno pre-contact population of several hundred thousand declined to sixty thousand by 1509. Although population estimates vary, Father Bartolomé de las Casas, the “Defender of the Indians” estimated there were 6 million (6,000,000) Taíno and Arawak in the Caribbean at the time of Columbus's arrival in 1492.[citation needed]

The population of the Native Amerindian population in Mexico declined by an estimated 90% (reduced to 1 - 2.5 million people) by the early 17th century. In Peru the indigenous Amerindian pre-contact population of around 6.5 million declined to 1 million by the early 17th century.[citation needed]

Of the history of the indigenous population of California, Sherburne F. Cook (1896–1974) was the most painstakingly careful researcher. From decades of research he made estimates for the pre-contact population and the history of demographic decline during the Spanish and post-Spanish periods. According to Cook, the indigenous Californian population at first contact, in 1769, was about 310,000 and had dropped to 25,000 by 1910. The vast majority of the decline happened after the Spanish period, in the Mexican and U.S. periods of Californian history (1821–1910), with the most dramatic collapse (200,000 to 25,000) occurring in the U.S. period (1846–1910).[11][12][13]

Cultural impact

The Spaniards were committed, by Vatican decree, to convert their New World indigenous subjects to Catholicism. However, often initial efforts were questionably successful, as the indigenous people added Catholicism into their longstanding traditional ceremonies and beliefs. The many native expressions, forms, practices, and items of art could be considered idolatry and prohibited or destroyed by Spanish missionaries, military, and civilians. This included religious items, sculptures, and jewelry made of gold or silver, which were melted down before shipment to Spain.

Though the Spanish did not impose their language to the extent they did their religion, some indigenous languages of the Americas evolved into replacement with Spanish, and lost to present day tribal members. When more efficient they did evangelize in native languages. Introduced writing systems to the Quechua, Nahuatl and Guarani peoples may have contributed to their expansion.[citation needed]

See also

References

- ^ "Presencia Hispánica en la Costa Noroeste de América (Siglo XVIII)" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-09-04.

- ^ Study of the Fundació d'Estudis Històrics de Catalunya[dead link]

- ^ "Source in Spanish". Cesarfrijol.tripod.com. Retrieved 2011-09-04.

- ^ Zinn, Howard (2003). A People's History Of The United States. New York: The New Press. p. 281. ISBN 978-1-56584-724-8.

- ^ Jane Penrose. Slings in the Iron Age. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ "Spanish Discovery and Colonization". U-s-history.com. 2011-08-17. Retrieved 2011-09-04.

- ^ "CAPÍTULO XXI | banrepcultural.org". Lablaa.org. Retrieved 2011-09-04.

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ "Migration to Latin America". Let.leidenuniv.nl. Retrieved 2011-09-04.

- ^ Baumhoff, Martin A. 1963. Ecological Determinants of Aboriginal California Populations. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 49:155-236.

- ^ Powers, Stephen. 1875. "California Indian Characteristics". Overland Monthly 14:297-309. on-line

- ^ Cook's judgement on the effects of U.S rule upon the native Californians is harsh: "The first (factor) was the food supply... The second factor was disease. ...A third factor, which strongly intensified the effect of the other two, was the social and physical disruption visited upon the Indian. He was driven from his home by the thousands, starved, beaten, raped, and murdered with impunity. He was not only given no assistance in the struggle against foreign diseases, but was prevented from adopting even the most elementary measures to secure his food, clothing, and shelter. The utter devastation caused by the white man was literally incredible, and not until the population figures are examined does the extent of the havoc become evident."Cook, Sherburne F. 1976b. The Population of the California Indians, 1769-1970. University of California Press, Berkeley|p. 200

Further reading

- David A. Brading, The First America: The Spanish Monarchy, Creole Patriots, and the Liberal State, I492-1867 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993).

- María M. Portuondo, Secret Science: Spanish Cosmography and the New World (Chicago, Chicago UP, 2009).

External links

- Wikipedia neutral point of view disputes from January 2010

- Spanish colonization of the Americas

- Colonial Mexico

- Colonial United States (Spanish)

- Colonization of the Americas

- Former empires

- Former Spanish colonies

- History of indigenous peoples of the Americas

- New Spain

- Spanish conquests in the Americas

- Viceroyalty of Peru

- 1525 establishments

- 1821 disestablishments