Spinning mule: Difference between revisions

ClemRutter (talk | contribs) →100 years of history: more in the next few days |

ClemRutter (talk | contribs) Change lead |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

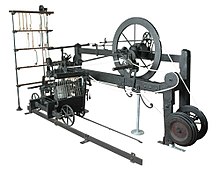

[[Image:Mule-jenny.jpg|thumb|The only surviving example of a spinning mule built by the inventor [[Samuel Crompton]]]] |

[[Image:Mule-jenny.jpg|thumb|The only surviving example of a spinning mule built by the inventor [[Samuel Crompton]]]] |

||

The '''spinning mule''' was a machine used to spin [[cotton]] and other fibres in the [[Cotton mill|mills]] of [[Lancashire]] and elsewhere during the nineteenth and early twenty century. Mules were worked in pairs by a minder, with the help of two boys: the little piecer and the big or side piecer. The carriage carried upto 1320 spindles and could be {{convert|150|ft|m}} long, and would move forward and back a distance of {{convert|5|ft|m}} four times a minute. 11. |

|||

| ⚫ | The |

||

It was invented between 1775–1779 by [[Samuel Crompton]]. The self acting mule was patented by Richard Roberts in 1820. At its peak there were 50,000,000 mule spindles in Lancashire alone. |

|||

| ⚫ | The spinning mule spins textile fibres into yarn by an intermittent process.<ref>{{harvnb|Marsden|1884|p=109}}</ref> In the draw stroke, the [[roving]] is pulled through rollers and twisted; on the return it is wrapped onto the spindle. Its rival, the [[throstle frame]] or [[Ring spinning|ring frame]] uses a continuous process, where the roving is drawn, twisted and wrapped in one action. The mule was the most common spinning machine from 1790 until about 1900 and was still used for fine yarns until the early 1980s. In 1890, a typical cotton mill would have over 60 mules, each with 1320 spindles.<ref>{{harvnb|Nasmith|1895|p=109}}</ref> which would operate four times a minute for 56 hours a week. |

||

==History== |

==History== |

||

Revision as of 20:28, 3 July 2011

The spinning mule was a machine used to spin cotton and other fibres in the mills of Lancashire and elsewhere during the nineteenth and early twenty century. Mules were worked in pairs by a minder, with the help of two boys: the little piecer and the big or side piecer. The carriage carried upto 1320 spindles and could be 150 feet (46 m) long, and would move forward and back a distance of 5 feet (1.5 m) four times a minute. 11. It was invented between 1775–1779 by Samuel Crompton. The self acting mule was patented by Richard Roberts in 1820. At its peak there were 50,000,000 mule spindles in Lancashire alone.

The spinning mule spins textile fibres into yarn by an intermittent process.[1] In the draw stroke, the roving is pulled through rollers and twisted; on the return it is wrapped onto the spindle. Its rival, the throstle frame or ring frame uses a continuous process, where the roving is drawn, twisted and wrapped in one action. The mule was the most common spinning machine from 1790 until about 1900 and was still used for fine yarns until the early 1980s. In 1890, a typical cotton mill would have over 60 mules, each with 1320 spindles.[2] which would operate four times a minute for 56 hours a week.

History

Before the 1770s, textile production was a cottage industry using flax and wool. In a typical house, the girls and women could make enough yarn for the man's loom. But demand overtook supply due to:

- pressure to compete with cotton calicos from India.

- the invention by John Kay of the flying shuttle (which made the loom twice as productive).

Two systems were developed from the spinning wheel: the Simple Wheel, which uses an intermittent process and the more refined Saxony wheel which drives a differential spindle and flyer with heck, in a continuous process. Development was sponsored by businessmen such as Arkwright who employed inventors, then took out the relevant patents.

The increased supply of yarn inspired developments in loom design such as Rev. Cartwright's power loom. Some spinners and handloom weavers opposed the perceived threat to their livelihood: there were frame-breaking riots and, in 1811-3, the Luddism riots. The preparatory and associated tasks allowed many children to be employed until this was regulated.

The hand operated mule was a breakthrough in yarn production and the machines were copied by Samuel Slater who founded the cotton industry in Rhode Island. Development over the next century and a half led to an automatic mule and to finer and stronger yarn. The ring frame, originating in New England in the 1820s was little used in Lancashire until the 1890s. It used more energy and could not produce the finest counts.[3]

The first mule

In 1779 Samuel Crompton invented the spinning mule or mule jenny, so called because it is a hybrid of Arkwright's water frame and Hargreaves' spinning jenny. The mule has a fixed frame with a creel of bobbins to hold the roving, connected through the headstock to a parallel carriage with the spindles. On the outward motion, the rovings are paid out and twisted. On the return, the roving is clamped and the spindles reversed to take up the newly spun thread.

Crompton built his mule from wood. Although he used Hargreaves' ideas of spinning multiple threads and of attenuating the roving with rollers, it was he who put the spindles on the carriage and fixed a creel of roving bobbins on the frame. Both the rollers and the outward motion of the carriage remove irregularities from the rove before it is wound on the spindle. When Arkwright's patents expired, the mule was developed by several manufacturers.[4]

The mule produced strong, thin yarn, suitable for any kind of textile. It was first used to spin cotton, then other fibres.

Samuel Crompton could not afford to patent his invention. He sold the rights to David Dale and returned to weaving. Dale patented the mule and profited from it.

Improvements

1790

- Kelly of Glasgow - a method of using power to assist the draw stroke.[5] First animals and then water.

- Wright of Manchester - moved the head stock to the centre of the machine allowing twice as many spindles, a squaring band was added to ensure the spindles came out in a straight line[6]

1793

- Kennedy addressed the problem of finer counts. With these the spindles on the return traverse needed to rotate faster than on the outward traverse. He attached gears and a clutch to implement this motion.[7]

1818

- William Eaton - improved the winding of the thread by using two faller wires and performing a backing off at the end of the outward traverse.[8]

Roberts' self-acting mule

Richard Roberts took out his first patent in 1825, and a second in 1830. The task he had set himself was to design a selfactor, a self-acting or automatic spinning mule. Roberts is also known for the Roberts Loom, which was widely adopted because of its reliability. The mule in 1820 still needed manual assistance to spin a consistent thread, a self-acting mule needed:

- A reversing mechanism that would unwind a spiral of yarn on the top of each spindle, before commencing the winding of a new stretch

- A faller wire that would ensure the yarn was wound into a predefined form such as a cop

- An appliance to vary the speed of revolution of the spindle, in accordance with the diameter of thread on that spindle

A counter faller under the thread was made to rise to take in the slack caused by backing off. This could be used with the top faller wire to guide the yarn to the correct place on the cop. These were controlled by levers and cams and an inclined plane called the shaper. The spindle speed was controlled by a drum and weighted ropes, as the headstock moved the ropes twisted the drum, which using a tooth wheel turned the spindles. None of this would have been possible using the technology of Crompton's time, fifty years earlier.[9]

-

A cross section 1882

-

The outward traverse

-

The inward traverse

-

Notice the faller wire gear

-

Selfactor in Vonwiller & Co., Žamberk, Austro-Hungaria

With the invention of the self actor, the hand operated mule was increasingly referred to as a mule-jenny.[10]

Oldham counts

Oldham counts refers to the medium thickness cotton that was used for general purpose cloth. Roberts didn't profit from his self-acting spinning mule, but on the expiry of the patent other firms took forward the development, and the mule was adapted for the counts it spun. Initially Robert's self actor was used for course counts (Oldham Counts) but the mule-jenny continued to be used for the very finest counts (Bolton counts) until the 1890s and beyond.[10]

Bolton counts

Bolton specialised in fine count cotton, its mules ran slower to put in the extra twist. The mule jenny allowed for this gentler action but in the twentieth century additional mechanisms were added to make the motion more gentle leading to mules that used two or even three driving speeds. Fine counts needed a softer action on the winding, and relied on manually adjustment to wind the chase or top of the perfect cop,[11]

Woollen mules

Spinning wool was very different, the staple was naturally twisted and easily adhered to other staples. The yarn could be bulked out by pressing in short fibres that would have been consider to short to spin if cotton. the mule could be far simpler in its construction.[12]

Condensor spinning

Condensor spinning or cotton waste spinning is akin to spinning wool, and the mules are similar.[13] Helmshore was a cotton waste mule spinning mill.

Operation of a mule

Mule spindles rest on a carriage that travels on a track a distance of 60 inches (1.5 m), while drawing out and spinning the yarn. On the return trip, known as putting up,[14] as the carriage moves back to its original position, the newly spun yarn is wound onto the spindle, in the form of a cone-shaped cop. As the mule spindle travels on its carriage, the roving which it spins is fed to it through rollers geared to revolve at different speeds to draw out the yarn.

Marsden in 1885 described the processes of setting up and operating a mule. Here is his description, edited slightly.

The creel holds bobbins containing rovings. The rovings are passed through small guide-wires, and between the three pairs of drawing-rollers.

- The first pair takes hold of the roving, to draw the roving or sliver from the bobbin, and deliver it to the next pair.

- The motion of the middle pair is slightly quicker than the first, but only sufficiently so to keep the roving

uniformly tense

- The front pair, running much more quickly, draws out (attenuates) the roving so it is equal throughout.

Connection is then established between the attenuated rovings and the spindles. When the latter are bare, as in a new mule, the spindle-driving motion is put into gear, and the attendants wind upon each spindle a short length of yarn from a cop held in the hand. The drawing-roller motion is placed in gear, and the rollers soon present lengths of attenuated roving. These are attached to the threads on the spindles, by simply placing the threads in contact with the un-twisted roving. The different parts of the machine are next simultaneously started, when the whole works in harmony together.

The back rollers pull the sliver from the bobbins, and passing it to the succeeding pairs, whose differential speeds attenuate it to the required degree of fineness. As it is delivered in front, the spindles, revolving at a rate of 6,000–9,000 rpm twist the hitherto loose fibres together, thus forming a thread.

Whilst this is going on, the spindle carriage is being drawn away from the rollers, at a pace very slightly exceeding the rate at which the roving is coming forth. This is called the gain of the carriage, its purpose being to eliminate all irregularities in the fineness of the thread. Should a thick place in the roving come through the rollers, it would resist the efforts of the spindle to twist it; and, if passed in this condition, it would seriously deteriorate the quality of the yarn, and impede subsequent operations. As, however, the twist, spreading itself over the level thread, gives firmness to this portion, the thick and untwisted part yields to the draught of the spindle, and, as it approaches the tenuity of the remainder, it receives the twist it had hitherto refused to take. The carriage, which is borne upon wheels, continues its outward progress, until it reaches the extremity of its traverse, which is 63 inches (160 cm) from the roller beam. The revolution of the spindles cease, the drawing rollers stop.

Backing-off commences. This process is the unwinding of the several turns of the yarn, extending from the top of the cop in process of formation to the summit of the spindle. As this proceeds, the faller- wire, which is placed over and guides the threads upon the cop, is depressed ; the counter-faller at the same time rising, the slack unwound from the spindles is taken up, and the threads are prevented from running into snarls. Backing-off is completed.

The carriage commences to run inwards; that is, towards the rollerbeam. This is called putting up. The spindles wind on the yarn at a uniform rate. The speed of revolution of the spindle must vary, as the faller is guiding the thread upon the larger or smaller diameter of the cone of the cop. Immediately the winding is finished, the depressed faller rises, the counter-faller is put down.

These movements are repeated until the cops on each spindle are perfectly formed: the ' set is completed.A stop-motion paralyzes every action of the machine, rendering it necessary to doff or strip the spindles, and to commence anew.

Doffing is performed by the attendants raising the cops partially up the spindles, whilst the carriage is out; then depressing the faller, so far as to guide the threads upon the bare spindle below. A few turns are wound on, to fix the threads to the spindles for a new set, and then the cops are removed, being collected into cans or baskets, and subsequently delivered to the warehouse. The remainder of the "draw" or "stretch," as the length of spun yarn is called when the carriage is out, is then wound upon the spindles by the carriage being run up to the roller beam. Work then commences anew. [15]

Key components

- Drawing rollers

- Faller and counter faller

Terminology

Social and economic

The spinning inventions were significant in enabling a great expansion to occur in the production of textiles, particularly cotton ones. Cotton and iron were leading sectors in the Industrial Revolution. Both industries underwent a great expansion at about the same time, which can be used to identify the start of the Industrial Revolution.

The 1790 mule was operated by brute force: the spinner drawing and pushing the frame while attending to each spindle. Home spinning was the occupation of women and girls, but the strength needed to operate a mule, caused it to be the activity of men. Hand loom weaving however, had been a man's occupation but in the mill it could and was done by girls and women. Spinners were the bare-foot aristocrats of the factory system.[16]

Mule spinners were the leaders in unionism within the cotton industry, the pressure to develop the self-actor or self acting mule was partly to open the trade to women. It was in 1870. that the first national union was formed.

The Wool industry was divided into woollen and worsted. It lagged behind cotton in adopting new technology. Worsted tended to adopt Arkwright water frames which could be operated by young girls, and woollen adopted the mule.[16]

Mule-spinners' cancer

About 1900 there was a high incidence of scrotal cancer detected in former mules spinners. It was limited to cotton mule spinners and did not affect woollen or condenser mule spinners. The cause was attributed to the blend of vegetable and mineral oils used to lubricate the spindles. The spindles when running threw out a mist of oil at crotch height, that was captured by the clothing of anyone piecing an end. In the 1920s much attention was given to this problem. Mules had used this mixture since the 1880s, and cotton mules ran faster and hotter than the other mules, and needed more frequent oiling. The solution was to make it a statutory requirement to only use vegetable oil or white mineral oils, which were believed to be non-carcinogens. By then cotton mules had been superseded by the ring frame and the industry was contracting, therefore it was never established if these measures were effective.[17]

See also

- Cotton mill

- Textile manufacture during the Industrial Revolution

- Textile manufacturing

- Timeline of clothing and textiles technology

References

- ^ Marsden 1884, p. 109

- ^ Nasmith 1895, p. 109

- ^ Saxonhouse, Gary. "Technological Evolution in Cotton Spinning, 1878-1933".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Marsden 1884, p. 219

- ^ a b Marsden 1884, p. 222

- ^ Marsden 1884, p. 223

- ^ Marsden 1884, p. 224

- ^ Marsden 1884, p. 226

- ^ Marsden 1884, pp. 226–230

- ^ a b Catling 1986, p. 51

- ^ Catling 1986, pp. 75–9, 118

- ^ Catling 1986, pp. 141–146

- ^ Catling 1986, p. 144

- ^ Miller & Wild 2007, p. 166

- ^ Marsden 1884, pp. 240–242

- ^ a b Fowler, Alan (11-13 Nov. 2004). "British Textile Workers in the Lancashire Cotton and Yorkshire Wool Industries". National overview Great Britain, Textile conference IISH,.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Catlin 1986, p. 179

Bibliography

- Catling, Harold (1986). The Spinning Mule. Preston: The Lancashire Library. ISBN 0902228617.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nasmith, Joseph (1895). Recent Cotton Mill Construction and Engineering (Elibron Classics ed.). London: John Heywood. ISBN 1-4021-4558-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Marsden, Richard (1884). Cotton Spinning: its development, principles an practice. George Bell and Sons 1903. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Marsden, ed. (1909). Cotton Yearbook 1910. Manchester: Marsden and Co. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Miller, I (2007). A& G Murray and the Cotton Mills of Ancoats. Storey Institute Lancaster: Oxford Archaeology North. ISBN 090422046X.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)*