Women's rights: Difference between revisions

reinstated rome section which got lost |

extended stoic section in greece and add stuff on stoic influence in rome |

||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

In ''[[The Republic (Plato)|The Republic]]'' the Athenian philosopher [[Plato]] referred to women as [[private property]] and [[Socrates]] discusses the "right acquisition and use of children and women" and "the law concerning the possession and rearing of the women and children". According to Socrates a state of ideal qualities was one where "women and children and house remain private, and all these things are established as the private property of individuals." [[Plato]] acknowledged that extending civil and political rights to women would substantively alter the nature of the household and the state.<ref>{{Cite book| last = Robinson| first = Eric W.| title = Ancient Greek democracy: readings and sources| publisher = Wiley-Blackwell| year = 2004| pages = 300| url = http://books.google.com/books?id=Jug6crxEImIC&dq=Aristophanes+ecclesiazusae+women%27s+rights&source=gbs_navlinks_s| isbn = 9780631233947 }}</ref> [[Aristotle]], who had been tought by Plato, denied that women were slaves or subject to property, arguing that "nature has distinguished between the female and the slave", but he considered wives to be "bought". He argued that women's main economic activity is that of safeguarding the household property created by men. According to Aristotle the labour of women added no value because "the art of household management is not identical with the art of getting wealth, for the one uses the material which the other provides".<ref>{{Cite book| last = Gerhard| first = Ute| title = Debating women’s equality: toward a feminist theory of law from a European perspective| publisher = Rutgers University Press| year = 2001| pages = 32–35| url = http://books.google.com/books?id=XMohyLfGDDsC&dq=women+right+to+property&source=gbs_navlinks_s| isbn = 9780813529059}}</ref> |

In ''[[The Republic (Plato)|The Republic]]'' the Athenian philosopher [[Plato]] referred to women as [[private property]] and [[Socrates]] discusses the "right acquisition and use of children and women" and "the law concerning the possession and rearing of the women and children". According to Socrates a state of ideal qualities was one where "women and children and house remain private, and all these things are established as the private property of individuals." [[Plato]] acknowledged that extending civil and political rights to women would substantively alter the nature of the household and the state.<ref>{{Cite book| last = Robinson| first = Eric W.| title = Ancient Greek democracy: readings and sources| publisher = Wiley-Blackwell| year = 2004| pages = 300| url = http://books.google.com/books?id=Jug6crxEImIC&dq=Aristophanes+ecclesiazusae+women%27s+rights&source=gbs_navlinks_s| isbn = 9780631233947 }}</ref> [[Aristotle]], who had been tought by Plato, denied that women were slaves or subject to property, arguing that "nature has distinguished between the female and the slave", but he considered wives to be "bought". He argued that women's main economic activity is that of safeguarding the household property created by men. According to Aristotle the labour of women added no value because "the art of household management is not identical with the art of getting wealth, for the one uses the material which the other provides".<ref>{{Cite book| last = Gerhard| first = Ute| title = Debating women’s equality: toward a feminist theory of law from a European perspective| publisher = Rutgers University Press| year = 2001| pages = 32–35| url = http://books.google.com/books?id=XMohyLfGDDsC&dq=women+right+to+property&source=gbs_navlinks_s| isbn = 9780813529059}}</ref> |

||

Plato's [[natural law]] theories were further developed by the [[Stoicism|Stoic school of philosophers]], founded by [[Zeno]].<ref>{{Cite book| last = Ratnapala| first = Suri| title = Jurisprudence| publisher = Cambridge University Press| date = 2009| pages =133 | url = http://books.google.com/books?id=tNwdWlXxZt8C&dq=Stoic+law+women&source=gbs_navlinks_s| isbn = 9780521614832 }}</ref> The degree to which Stoic philosophers emphasised women’s' rights varied. Stoic philosophy on human nature and natural law was later influenced by [[Cynicism|Cynics]] philosophers, who argued that men and women should receive the same kind of education and saw saw marriage as a moral companionship between equals rather than a biological or social necessity. Panaetius further developed the Stoic philosophy on the application of ethical principles to all people, so strengthening the case for the equality of women.<ref name="Colish">{{cite book |title=The Stoic Tradition from Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages: Stoicism in classical Latin literature |last=Colish |first=Marcia L. |year=1990 |publisher=BRILL |isbn=9789004093270 |page=37-38 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=WY-2MeZqoK0C&pg=PA36&dq=stoics%2Bslavery&hl=en&ei=6hoMTeaoFoXGsAPK482mDw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CCkQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=stoics%2Bslavery&f=false}}</ref> |

|||

=== Rome === |

=== Rome === |

||

Stoic philosophies had a strong effect on the development of law in [[ancient Rome]]. Early law considered a wife a minor, a ward, a person incapable of doing or acting anything according to her own individual taste, a person continually under the tutelage and guardianship of her husband. Under Roman Law a woman and her property passed into the power of her husband upon marriage. The wife was considered the purchased [[property]] of her husband, acquired only for his benefit. Furthermore [[women in Ancient Rome]] could not exercise any civil or public office, and could not act as witness, surety, tutor, or curator. The Roman stoic thinkers [[Seneca]] and [[Musonius Rufus]] further developed theories of equality, arguing that nature gives men and women equal capacity for virtue and equal obligations. Therefore they argued that men and women have an equal need for philosophical education.<ref name="Colish"/> Stoic theories entered Roman law first through the Roman lawyer and sentaor [[Marcus Tullius Cicero]] and the status of women in law improved gradually as Stoic influence increased.<ref>{{Cite book| last = Ratnapala| first = Suri| title = Jurisprudence| publisher = Cambridge University Press| date = 2009| pages =134-135 | url = http://books.google.com/books?id=tNwdWlXxZt8C&dq=Stoic+law+women&source=gbs_navlinks_s| isbn = 9780521614832 }}</ref> |

|||

=== Religious scriptures === |

=== Religious scriptures === |

||

Revision as of 21:23, 5 February 2011

| Rights |

|---|

|

| Theoretical distinctions |

| Human rights |

| Rights by beneficiary |

| Other groups of rights |

Women's rights are entitlements and freedoms claimed for women and girls of all ages in many societies.

In some places these rights are institutionalized or supported by law, local custom, and behaviour, whereas in others they may be ignored or suppressed. They differ from broader notions of human rights through claims of an inherent historical and traditional bias against the exercise of rights by women and girls in favour of men and boys.[1]

Issues commonly associated with notions of women's rights include, though are not limited to, the right: to bodily integrity and autonomy; to vote (suffrage); to hold public office; to work; to fair wages or equal pay; to own property; to education; to serve in the military or be conscripted; to enter into legal contracts; and to have marital, parental and religious rights.[2]

History of women's rights

Greece

The status of women in ancient Greece varied form city state to city state. Records exist of women in ancient Delphi, Gortyn, Thessaly, Megara and Sparta owning land, the most prestigious form of private property at the time.[3] While Spartan women were excluded from military and political life they enjoyed considerable status as mothers of Spartan warriors. As men engaged in military activity women took responsibility for running estates. Following protracted war in the 4 Century Spartan women owned approximately two fifth of all Spartan land and property.[4]

Athenian women had no right to property and therefore were not considered full citizens, as citizenship and the entitlement to civil and political rights was defined in relation to property and the means to life.[5] By law Athenian women could not enter into a contract worth more than the value of a “medimnos of barley” (a measure of grain), allowing women to engage in petty trading. In law Athenian women had no legal personhood and was assumed to be part of the oikos headed by the male kyrios. Until marriage, women were under the guardianship of their father or other male relative, once married the husband became a women’s kyrios. As women were bared from conducting legal proceedings, the kyrios would do so on their behalf.[6] Women could quire rights over property through gifts, dowry and inheritance, though her kyrios had the right to dispose of a women’s property.[7] In 451-450 BC the law was changed, requiring both parents to be Athenian for citizenship to be conferred on a men.[8] Though women, like slaves, were not eligible for full citizenship in ancient Athens, though in rare circumstances they could become citizens if freed. The only permanent barrier to citizenship, and hence full political and civil rights, in ancient Athens was gender. No women ever acquired citizenship in ancient Athens, and therefore women were excluded in principle and practice from ancient Athenian democracy.[9]

In The Republic the Athenian philosopher Plato referred to women as private property and Socrates discusses the "right acquisition and use of children and women" and "the law concerning the possession and rearing of the women and children". According to Socrates a state of ideal qualities was one where "women and children and house remain private, and all these things are established as the private property of individuals." Plato acknowledged that extending civil and political rights to women would substantively alter the nature of the household and the state.[10] Aristotle, who had been tought by Plato, denied that women were slaves or subject to property, arguing that "nature has distinguished between the female and the slave", but he considered wives to be "bought". He argued that women's main economic activity is that of safeguarding the household property created by men. According to Aristotle the labour of women added no value because "the art of household management is not identical with the art of getting wealth, for the one uses the material which the other provides".[11]

Plato's natural law theories were further developed by the Stoic school of philosophers, founded by Zeno.[12] The degree to which Stoic philosophers emphasised women’s' rights varied. Stoic philosophy on human nature and natural law was later influenced by Cynics philosophers, who argued that men and women should receive the same kind of education and saw saw marriage as a moral companionship between equals rather than a biological or social necessity. Panaetius further developed the Stoic philosophy on the application of ethical principles to all people, so strengthening the case for the equality of women.[13]

Rome

Stoic philosophies had a strong effect on the development of law in ancient Rome. Early law considered a wife a minor, a ward, a person incapable of doing or acting anything according to her own individual taste, a person continually under the tutelage and guardianship of her husband. Under Roman Law a woman and her property passed into the power of her husband upon marriage. The wife was considered the purchased property of her husband, acquired only for his benefit. Furthermore women in Ancient Rome could not exercise any civil or public office, and could not act as witness, surety, tutor, or curator. The Roman stoic thinkers Seneca and Musonius Rufus further developed theories of equality, arguing that nature gives men and women equal capacity for virtue and equal obligations. Therefore they argued that men and women have an equal need for philosophical education.[13] Stoic theories entered Roman law first through the Roman lawyer and sentaor Marcus Tullius Cicero and the status of women in law improved gradually as Stoic influence increased.[14]

Religious scriptures

Qur'an

The Qur'an, written down by Muhammad over the course of 23 years, provide guidance to the Islamic community and modified existing customs in Arab society. From 610 and 661, known as the early reforms under Islam, the Qur'an introduced fundamental reforms to customary law and introduced rights for women in marriage, divorce and inheritance. By providing that the wife, not her family, would receive a dowry from the husband, which she could administer as her personal property, the Qur'an made women a legal party to the marriage contract.[citation needed]

While in customary law inheritance was limited to male descendents, the Qur'an introduced rules on inheritance with certain fixed shares being distributed to designated heirs, first to the nearest female relatives and then the nearest male relatives.[15] According to Annemarie Schimmel "compared to the pre-Islamic position of women, Islamic legislation meant an enormous progress; the woman has the right, at least according to the letter of the law, to administer the wealth she has brought into the family or has earned by her own work."[16]

The general improvement of the status of Arab women included prohibition of female infanticide and recognizing women's full personhood.[17] Women were generally given greater rights than women in pre-Islamic Arabia[18][19] and medieval Europe.[20] Women were not accorded with such legal status in other cultures until centuries later.[21] According to Professor William Montgomery Watt, when seen in such historical context, Muhammad "can be seen as a figure who testified on behalf of women’s rights."[22]

The Middle Ages

According to English Common Law, which developed from the 12th Century onward, all property which a wife held at the time of a marriage became a possession of her husband. Eventually English courts forbade a husband's transferring property without the consent of his wife, but he still retained the right to manage it and to receive the money which it produced. French married women suffered from restrictions on their legal capacity which were removed only in 1965.[23] In the 16th century, the Reformation in Europe allowed more women to add their voices, including the English writers Jane Anger, Aemilia Lanyer, and the prophetess Anna Trapnell. English and American Quakers rejected family hierarchy, holding all members equal before God. Many Quaker women were preachers.[24] Despite relatively greater freedom for Anglo-Saxon women, until the mid-19th century, writers largely assumed that a patriarchal order was a natural order that had always existed.[25] This perception was not seriously challenged until the 18th century when Jesuit missionaries found matrilineality in native North American peoples.[26]

18th and 19th century Europe

Starting in the late 18th century, and throughout the 19th century, rights, as a concept and claim, gained increasing political, social and philosophical importance in Europe. Movements emerged which demanded freedom of religion, the abolition of slavery, rights for women, rights for those who did not own property and universal suffrage.[28] In the late 18th Century the question of women's rights became central to political debates in both France and Britain. At the time some of the greatest thinkers of the Enlightenment, who defended democratic principles of equality and challenged notions that a privileged few should rule over the vast majority of the population, believed that these principles should be applied only to their own gender and their own race. The philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau for example thought that it was the order of nature for woman to obey men. He wrote "Women do wrong to complain of the inequality of man-made laws" and claimed that "when she tries to usurp our rights, she is our inferior".[29]

In 1791 the French playwright and political activist Olympe de Gouges published the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen,[30] modelled on the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 1789. The Declaration is ironic in formulation and exposes the failure of the French Revolution, which had been devoted to equality. It states that: “This revolution will only take effect when all women become fully aware of their deplorable condition, and of the rights they have lost in society”. The Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen follows the seventeen articles of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen point for point and has been described by Camille Naish as “almost a parody... of the original document”. The first article of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen proclaims that “Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be based only on common utility.” The first article of Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen replied: “Woman is born free and remains equal to man in rights. Social distinctions may only be based on common utility”. De Gouges expands the sixth article of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, which declared the rights of citizens to take part in the formation of law, to:

“All citizens including women are equally admissible to all public dignities, offices and employments, according to their capacity, and with no other distinction than that of their virtues and talents”.

De Gouges also draws attention to the fact that under French law women were fully punishable, yet denied equal rights.[31]

Mary Wollstonecraft, a British writer and philosopher, published A Vindication of the Rights of Woman in 1792, arguing that it was the education and upbringing of women that created limited expectations.[32][33] Wollstonecraft attacked gender oppression, pressing for equal educational opportunities, and demanded "justice!" and "rights to humanity" for all.[34] Wollstonecraft, along with her British contemporaries Damaris Cudworth and Catherine Macaulay started to use the language of rights in relation to women, arguing that women should have greater opportunity because like men, they were moral and rational beings.[35]

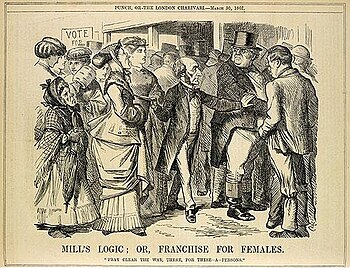

In his 1869 essay The Subjection of Women the English philosopher and political theorist John Stuart Mill described the situation for women in Britain as follows:

"We are continually told that civilization and Christianity have restored to the woman her just rights. Meanwhile the wife is the actual bondservant of her husband; no less so, as far as the legal obligation goes, than slaves commonly so called."

The a member of parliament Mill argued that women should be given the right to vote, though his proposal to replace the term 'man' with 'person' in the second Reform Bill of 1867 was greeted with laughter in the House of Commons and defeated by 76 to 196 votes. His arguments won little support amongst contemporaries[36] but his attempt to amend the reform bill generated greater attention for the issue of women's suffrage in Britain.[37] Initially only one of several women’s rights campaign, suffrage became the primary cause of the British women’s movement at the beginning of the 20th Century.[38] At the time the ability to vote was restricted to wealthy property owners within British jurisdictions. This arrangement implicitly excluded women as property law and marriage law gave men ownership rights at marriage or inheritance until the 19th century. Although male suffrage broadened during the century, women were explicitly prohibited from voting nationally and locally in the 1830s by a Reform Act and the Municipal Corporations Act.[39] Millicent Fawcett and Emmeline Pankhurst led the public campaign on women's suffrage and in 1918 a bill was passed allowing women over the age of 30 to vote.[39]

Suffrage, the right to vote

During the 19th Century women began to agitate for the right to vote and participate in government and law making.[40] The ideals of women's suffrage developed alongside that of universal suffrage and today women's suffrage is considered a right (under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women).[citation needed] During the 19th Century the right to vote was gradually extended in many countries and women started to campaign for their right to vote. In 1893 New Zealand became the first country to give women the right to vote on a national level. Australia gave women the right to vote in 1902.[37] A number of Nordic countries gave women the right to vote in the early 20th Century – Finland (1906), Norway (1913), Denmark and Iceland (1915). With the end of the First World War many other countries followed – the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and the Netherlands (1917), Austria, Canada, Czechoslovakia, Poland and Sweden (1918), Germany and Lunenburg (1919), and the United States (1920) . Spain gave women the right to vote in 1931, France in 1944, Belgium, Italy, Romania and Yugoslavia in 1946. Switzerland gave women the right to vote in 1971, and Liechtenstein in 1984.[37]

In Latin America some countries gave women the right to vote in the first half of the 20th Century – Ecuador (1929), Brazil (1932), El Salvador (1939), Dominican Republic (1942), Guatemala (1956) and Argentina (1946). In India, under colonial rule, universal suffrage was granted in 1935. Other Asian countries gave women the right to vote in mid of the 20th Century – Japan (1945), China (1947) and Indonesia (1955). In Africa women generally got the right to vote along with men through universal suffrage – Liberia (1947), Uganda (1958) and Nigeria (1960). In many countries in the Middle East universal suffrage was acquired after the Second World War, although in others, such as Kuwait, suffrage is very limited.[37] On 16 May 2005, the Parliament of Kuwait extended suffrage to women by a 35–23 vote.[41]

Property rights

During the 19th century women in the United States and Britain began to challenge laws that denied them the right to their property once they married. Under the common law doctrine of coverture husbands gained control of their wives' real estate and wages. Beginning in the 1840s, state legislatures in the United States[42] and the British Parliament[43] began passing statutes that protected women's property from their husbands and their husbands' creditors. These laws were known as the Married Women's Property Acts.[44] Courts in the 19th-century United States also continued to require privy examinations of married women who sold their property. A privy examination was a practice in which a married woman who wished to sell her property had to be separately examined by a judge or justice of the peace outside of the presence of her husband and asked if her husband was pressuring her into signing the document.[45]

Modern movements

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (December 2010) |

In the subsequent decades women's rights again became an important issue in the English speaking world. By the 1960s the movement was called "feminism" or "women's liberation." Reformers wanted the same pay as men, equal rights in law, and the freedom to plan their families or not have children at all. Their efforts were met with mixed results.[46]

In the UK, a public groundswell of opinion in favour of legal equality had gained pace, partly through the extensive employment of women in what were traditional male roles during both world wars. By the 1960s the legislative process was being readied, tracing through MP Willie Hamilton's select committee report, his equal pay for equal work bill,[47] the creation of a Sex Discrimination Board, Lady Sear's draft sex anti-discrimination bill, a government Green Paper of 1973, until 1975 when the first British Sex Discrimination Act, an Equal Pay Act, and an Equal Opportunities Commission came into force.[48][49] With encouragement from the UK government, the other countries of the EEC soon followed suit with an agreement to ensure that discrimination laws would be phased out across the European Community.

In the USA, the National Organization for Women (NOW) was created in 1966 with the purpose of bringing about equality for all women. NOW was one important group that fought for the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). This amendment stated that "equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any state on account of sex."[50] But there was disagreement on how the proposed amendment would be understood. Supporters believed it would guarantee women equal treatment. But critics feared it might deny women the right be financially supported by their husbands. The amendment died in 1982 because not enough states had ratified it. ERAs have been included in subsequent Congresses, but have still failed to be ratified.[51]

Birth control and reproductive rights

In the 1870s feminists advanced the concept of voluntary motherhood as a political critique of involuntary motherhood[52] and expressing a desire for women's emancipation.[53] Advocates for voluntary motherhood disapproved of contraception, arguing that women should only engage in sex for the purpose of procreation[54] and advocated for periodic or permanent abstinence.[55]

In the early 20th Century birth control was advanced as alternative to the then fashionable terms family limitation and voluntary motherhood.[57][58] The phrase "birth control" entered the English language in 1914 and was popularised by Margaret Sanger,[57][58] who was mainly active in the US but had gained an international reputation by the 1930s. The British birth control campaigner Marie Stopes made contraception acceptable in Britain during the 1920 by framing it in scientific terms. Stopes assisted emerging birth control movements in a number of British colonies.[59] The birth control movement advocated for contraception so as to permit sexual intercourse as desired without the risk of pregnancy.[55] By emphasising control the birth control movement argued that women should have control over their reproduction and the movement had close ties to the feminist movement. Slogans such as "control over our own bodies" criticised male domination and demanded women's liberation, a connotation that is absent from the family planning, population control and eugenics movements.[60] In the 1960s and 1970s the birth control movement advocated for the legalisation of abortion and large scale education campaigns about contraception by governments.[61] In the 1980s birth control and population control organisations co-operated in demanding rights to contraception and abortion, with an increasing emphasis on "choice".[60]

Birth control has become a major themes in feminist politics who cited reproduction issues as examples of women's powerlessness to exercise their rights.[62] The societal acceptance of birth control required the separation of sex from procreation, making birth control a highly controversial subject in the 20th Century.[61] In a broader context birth control has become an arena for conflict between liberal and conservative values, raising questions about family, personal freedom, state intervention, religion in politics, sexual morality and social welfare.[62] Reproductive rights, that is rights relating to sexual reproduction and reproductive health,[63] were first discussed as a subset of human rights at the United Nation's 1968 International Conference on Human Rights.[64] Reproductive rights are not recognised in international human rights law and is an umbrella term that may include some or all of the following rights: the right to legal or safe abortion, the right to control one's reproductive functions, the right to access quality reproductive healthcare, and the right to education and access in order to make reproductive choices free from coercion, discrimination, and violence.[65] Reproductive rights may also be understood to include education about contraception and sexually transmitted infections, and freedom from coerced sterilization and contraception, protection from gender-based practices such as female genital cutting, or FGC, and male genital mutilation, or MGM.[63][64][65][66] Reproductive rights are understood as rights of both men and women, but are most frequently advanced as women's rights.[64]

Women's access to legal abortions is restricted by law in most countries in the world.[67] Where abortion is permitted by law, women may only have limited access to safe abortion services. Only a small number of countries prohibit abortion in all cases. In most countries and jurisdictions, abortion is allowed to save the pregnant woman's life, or where the pregnancy is the result of rape or incest.[68] According to Human Rights Watch "Abortion is a highly emotional subject and one that excites deeply held opinions. However, equitable access to safe abortion services is first and foremost a human right. Where abortion is safe and legal, no one is forced to have one. Where abortion is illegal and unsafe, women are forced to carry unwanted pregnancies to term or suffer serious health consequences and even death. Approximately 13% of maternal deaths worldwide are attributable to unsafe abortion—between 68,000 and 78,000 deaths annually."[68] According to Human Rights Watch "the denial of a pregnant woman's right to make an independent decision regarding abortion violates or poses a threat to a wide range of human rights."[69][70] Other groups however, such as the Catholic Church, the Christian right and most Orthodox Jews, regard abortion not as a right but as a 'moral evil'.[71]

United Nations and World Conferences on Women

In 1946 the United Nations established a Commission on the Status of Women.[72][73] Originally as the Section on the Status of Women, Human Rights Division, Department of Social Affairs, and now part of the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). Since 1975 the UN has held a series of world conferences on women's issues, starting with the World Conference of the International Women's Year in Mexico City. These conferences created an international forum for women's rights, but also illustrated divisions between women of different cultures and the difficulties of attempting to apply principles universally.[74] Four World Conferences have been held, the first in Mexico City (International Women's Year, 1975), the second in Copenhagen (1980) and the third in Nairobi (1985). At the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing (1995), The Platform for Action was signed. This included a commitment to achieve "gender equality and the empowerment of women".[75][76]

Natural law and women's rights

17th century natural law philosophers in Britain and America, such as Thomas Hobbes and John Locke, developed the theory of natural rights in reference to ancient philosophers such as Aristotle and the Christian theologise Aquinas. Like the ancient philosophers, 17th century natural law philosophers defended slavery and an inferior status of women in law.[77] Relying on ancient Greek philosophers, natural law philosophers argued that natural rights where not derived from god, but were "universal, self-evident, and intuitive", a law that could be found in nature. They believed that natural rights were self-evident to "civilised man" who lives "in the highest form of society".[78] Natural rights derived from human nature, a concept first established by the ancient Greek philosopher Zeno of Citium in Concerning Human Nature. Zenon argued that each rational and civilized male Greek citizen had a "divine spark" or "soul" within him that existed independent of the body. Zeno founded the Stoic philosophy and the idea of a human nature was adopted by other Greek philosophers, and later natural law philosophers and western humanists.[79] Aristotle developed the widely adopted idea of rationality, arguing that man was a "rational animal" and as such a natural power of reason. Concepts of human nature in ancient Greece depended on gender, ethnic, and other qualifications[80] and 17th Century natural law philosophers came to regard women along with children, slaves and non-whites, as neither "rational" nor "civilised".[78] Natural law philosophers claimed the inferior status of women was "common sense" and a matter of "nature". They believed that women could not be treated as equal due to their "inner nature".[77] The views of 17th Century natural law philosophers were opposed in the 18th and 19th Century by Evangelical natural theology philosophers such as William Wilberforce and Charles Spurgeon, who argued for the abolition of slavery and advocated for women to have rights equal to that of men.[77] Modern natural law theorist, and advocates of natural rights, claim that all people have a human nature, regardless of gender, ethnicity or other qualifications, therefore all people have natural rights.[80]

Human rights and women's rights

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women

Signed and ratified Acceded or succeeded Unrecognized state, abiding by treaty | Only signed Non-signatory |

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted in 1948, enshrines "the equal rights of men and women", and addressed both the equality and equity issues.[81] In 1979 the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). Described as an international bill of rights for women, it came into force on 3 September 1981. The seven UN member states that have not signed the convention are Iran, Nauru, Palau, Somalia, Sudan, Tonga, and the United States. Niue and the Vatican City have also not ratified it. The United States has signed, but not yet ratified.[82]

The Convention defines discrimination against women in the following terms:

Any distinction, exclusion or restriction made on the basis of sex which has the effect or purpose of impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment or exercise by women, irrespective of their marital status, on a basis of equality of men and women, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural, civil or any other field.

It also establishes an agenda of action for putting an end to sex-based discrimination for which states ratifying the Convention are required to enshrine gender equality into their domestic legislation, repeal all discriminatory provisions in their laws, and enact new provisions to guard against discrimination against women. They must also establish tribunals and public institutions to guarantee women effective protection against discrimination, and take steps to eliminate all forms of discrimination practiced against women by individuals, organizations, and enterprises.[citation needed]

Maputo Protocol

The Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa, better known as the Maputo Protocol, was adopted by the African Union on 11 July 2003 at its second summit in Maputo,[83] Mozambique. On 25 November 2005, having been ratified by the required 15 member nations of the African Union, the protocol entered into force.[84] The protocol guarantees comprehensive rights to women including the right to take part in the political process, to social and political equality with men, and to control of their reproductive health, and an end to female genital mutilation[85]

Rape and sexual violence

Rape, sometimes called sexual assault, is an assault by a person involving sexual intercourse with or sexual penetration of another person without that person's consent. Rape is generally considered a serious sex crime as well as a civil assault. When part of a widespread and systematic practice rape and sexual slavery are now recognised as crime against humanity and war crime. Rape is also now recognised as an element of the crime of genocide when committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a targeted group.

Rape as an element of the crime of genocide

In 1998, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda established by the United Nations made landmark decisions that rape is a crime of genocide under international law. The trial of Jean-Paul Akayesu, the mayor of Taba Commune in Rwanda, established precedents that rape is an element of the crime of genocide. The Akayesu judgement includes the first interpretation and application by an international court of the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. The Trial Chamber held that rape, which it defined as "a physical invasion of a sexual nature committed on a person under circumstances which are coercive", and sexual assault constitute acts of genocide insofar as they were committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a targeted group, as such. It found that sexual assault formed an integral part of the process of destroying the Tutsi ethnic group and that the rape was systematic and had been perpetrated against Tutsi women only, manifesting the specific intent required for those acts to constitute genocide.[86]

Judge Navanethem Pillay said in a statement after the verdict: “From time immemorial, rape has been regarded as spoils of war. Now it will be considered a war crime. We want to send out a strong message that rape is no longer a trophy of war.”[87] An estimated 500,000 women were raped during the 1994 Rwandan Genocide.[88]

Rape and sexual enslavement as crime against humanity

The Rome Statute Explanatory Memorandum, which defines the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court, recognises rape, sexual slavery, enforced prostitution, forced pregnancy, enforced sterilization, "or any other form of sexual violence of comparable gravity" as crime against humanity if the action is part of a widespread or systematic practice.[89][90] The Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action also condemn systematic rape as well as murder, sexual slavery, and forced pregnancy, as the "violations of the fundamental principles of international human rights and humanitarian law." and require a particularly effective responce.[91]

Rape was first recognised as crime against humanity when the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia issued arrest warrants based on the Geneva Conventions and Violations of the Laws or Customs of War. Specifically, it was recognised that Muslim women in Foca (southeastern Bosnia and Herzegovina) were subjected to systematic and widespread gang rape, torture and sexual enslavement by Bosnian Serb soldiers, policemen, and members of paramilitary groups after the takeover of the city in April 1992.[92] The indictment was of major legal significance and was the first time that sexual assaults were investigated for the purpose of prosecution under the rubric of torture and enslavement as a crime against humanity.[92] The indictment was confirmed by a 2001 verdict by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia that rape and sexual enslavement are crimes against humanity. This ruling challenged the widespread acceptance of rape and sexual enslavement of women as intrinsic part of war.[93] The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia found three Bosnian Serb men guilty of rape of Bosniac (Bosnian Muslim) women and girls (some as young as 12 and 15 years of age), in Foca, eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina. Furthermore two of the men were found guilty of the crime against humanity of sexual enslavement for holding women and girls captive in a number of de facto detention centres. Many of the women subsequently disappeared.[93]

| Part of a series on |

| Feminism |

|---|

|

|

|

See also

- Female education

- Feminism in 1950s Britain

- History of feminism

- Legal rights of women in history

- List of suffragists and suffragettes

- List of women's rights activists

- Pregnant patients' rights

- Sex workers' rights

- Timeline of women's rights (other than voting)

- Women's Social and Political Union

References

- ^ Hosken, Fran P., 'Towards a Definition of Women's Rights' in Human Rights Quarterly, Vol. 3, No. 2. (May, 1981), pp. 1–10.

- ^ Lockwood, Bert B. (ed.), Women's Rights: A "Human Rights Quarterly" Reader (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006), ISBN 978-0-8018-8374-3

- ^ Gerhard, Ute (2001). Debating women’s equality: toward a feminist theory of law from a European perspective. Rutgers University Press. p. 33. ISBN 9780813529059.

- ^ Tierney, Helen (1999). Women’s studies encyclopaedia, Volume 2. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 609–610. ISBN 9780313310720.

- ^ Gerhard, Ute (2001). Debating women’s equality: toward a feminist theory of law from a European perspective. Rutgers University Press. p. 35. ISBN 9780813529059.

- ^ Blundell, Sue (1995). Women in ancient Greece, Volume 1995, Part 2. Harvard University Press. p. 114. ISBN 9780674954731.

- ^ Blundell, Sue (1995). Women in ancient Greece, Volume 1995, Part 2. Harvard University Press. p. 115. ISBN 9780674954731.

- ^ Blundell, Sue (1995). Women in ancient Greece, Volume 1995, Part 2. Harvard University Press. p. 119. ISBN 9780674954731.

- ^ Robinson, Eric W. (2004). Ancient Greek democracy: readings and sources. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 302. ISBN 9780631233947.

- ^ Robinson, Eric W. (2004). Ancient Greek democracy: readings and sources. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 300. ISBN 9780631233947.

- ^ Gerhard, Ute (2001). Debating women’s equality: toward a feminist theory of law from a European perspective. Rutgers University Press. pp. 32–35. ISBN 9780813529059.

- ^ Ratnapala, Suri (2009). Jurisprudence. Cambridge University Press. p. 133. ISBN 9780521614832.

- ^ a b Colish, Marcia L. (1990). The Stoic Tradition from Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages: Stoicism in classical Latin literature. BRILL. p. 37-38. ISBN 9789004093270.

- ^ Ratnapala, Suri (2009). Jurisprudence. Cambridge University Press. pp. 134–135. ISBN 9780521614832.

- ^ Esposite, John L. (2001). Women in Muslim family law. Syracuse University Press. pp. 3–5. ISBN 9780815629085.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Schimmel, Annemarie (1992). Islam. SUNY Press. p. 65. ISBN 9780791413272.

- ^ Esposito (2004), p. 339

- ^ John Esposito, Islam: The Straight Path p. 79

- ^ Majid Khadduri, Marriage in Islamic Law: The Modernist Viewpoints, American Journal of Comparative Law, Vol. 26, No. 2, pp. 213–218

- ^ Encyclopedia of religion, second edition, Lindsay Jones, p.6224, ISBN 0-02-865742-X

- ^ Lindsay Jones, p.6224

- ^ Interview with Prof William Montgomery Watt

- ^ Badr, Gamal M.; Mayer, Ann Elizabeth (Winter 1984). "Islamic Criminal Justice". The American Journal of Comparative Law. 32 (1). American Society of Comparative Law: 167–169 167–8. doi:10.2307/840274.

- ^ W. J. Rorabaugh, Donald T. Critchlow, Paula C. Baker (2004). "America's promise: a concise history of the United States". Rowman & Littlefield. p.75. ISBN 0742511898

- ^ Maine, Henry Sumner. Ancient Law 1861

- ^ Lafitau, Joseph François, cited by Campbell, Joseph in, Myth, religion, and mother-right: selected writings of JJ Bachofen. Manheim, R (trans.) Princeton, N.J. 1967 introduction xxxiii

- ^ Tomory, Peter. The Life and Art of Henry Fuseli. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1972; p. 217. LCCN 72-0 – 0.

- ^ Sweet, William (2003). Philosophical theory and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. University of Ottawa Press. p. 4. ISBN 9780776605586.

- ^ Lauren, Paul Gordon (2003). The evolution of international human rights: visions seen. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 29 & 30. ISBN 9780812218541.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Macdonald and Scherf, "Introduction", 11–12.

- ^ Naish, Camille (1991). Death comes to the maiden: Sex and Execution, 1431–1933. Routledge. p. 137. ISBN 978-0415055857.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Brody, Miriam. Mary Wollstonecraft: Sexuality and women's rights (1759–1797), in Spender, Dale (ed.) Feminist theorists: Three centuries of key women thinkers, Pantheon 1983, pp. 40–59 ISBN 0-394-53438-7

- ^ Walters, Margaret, Feminism: A very short introduction (Oxford, 2005), ISBN 978019280510X

- ^ Lauren, Paul Gordon (2003). The evolution of international human rights: visions seen. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 32. ISBN 9780812218541.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Sweet, William (2003). Philosophical theory and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. University of Ottawa Press. p. 10. ISBN 9780776605586.

- ^ a b "Brave new world – Women's rights". National Archives. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Women's Suffrage". Scholastic. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- ^ Van Wingerden, Sophia A. (1999). The women’s suffrage movement in Britain, 1866–1928. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 1–2. ISBN 0312218532.

- ^ a b Phillips, Melanie, The Ascent of Woman: A History of the Suffragette Movement (Abacus, 2004)

- ^ Krolokke, Charlotte and Anne Scott Sorensen, 'From Suffragettes to Grrls' in Gender Communication Theories and Analyses:From Silence to Performance (Sage, 2005)

- ^ "Kuwait grants women right to vote" CNN.com (May 16, 2005)

- ^ http://womenshistory.about.com/od/marriedwomensproperty/a/property_1848ny.htm

- ^ http://www.umd.umich.edu/casl/hum/eng/classes/434/geweb/PROPERTY.htm

- ^ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/366305/Married-Womens-Property-Acts

- ^ http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/journal_of_womens_history/v012/12.2braukman.html

- ^ [1]

- ^ "Tributes paid to veteran anti-royalist". BBC News. 27 January 2000.

- ^ The Guardian, 29 December 1975

- ^ The Times, 29 December 1975 "Sex discrimination in advertising banned"

- ^ The National Organization for Women's 1966 Statement of Purpose

- ^ National Organization for Women: Definition and Much More from Answers.com

- ^ Gordon, Linda (2002). The moral property of women: a history of birth control politics in America. University of Illinois Press. p. 55. ISBN 9780252027642.

- ^ Gordon, Linda (2002). The moral property of women: a history of birth control politics in America. University of Illinois Press. p. 56. ISBN 9780252027642.

- ^ Gordon, Linda (2002). The moral property of women: a history of birth control politics in America. University of Illinois Press. p. 57. ISBN 9780252027642.

- ^ a b Gordon, Linda (2002). The moral property of women: a history of birth control politics in America. University of Illinois Press. p. 59. ISBN 9780252027642.

- ^ Sanger, Margaret (July 1919), "How Shall we Change the Law", Birth Control Review (3): 8–9

- ^ a b Wilkinson Meyer, Jimmy Elaine (2004). Any friend of the movement: networking for birth control, 1920-1940. Ohio State University Press. p. 184. ISBN 9780814209547.

- ^ a b Galvin, Rachel. "Margaret Sanger's "Deeds of Terrible Virtue"". National Endowment for the Humanities. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ Blue, Gregory (2002). Colonialism and the modern worls: selected studies. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 182–183. ISBN 9780765607720.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Gordon, Linda (2002). The moral property of women: a history of birth control politics in America. University of Illinois Press. p. 297. ISBN 9780252027642.

- ^ a b Gordon, Linda (2002). The moral property of women: a history of birth control politics in America. University of Illinois Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 9780252027642.

- ^ a b Gordon, Linda (2002). The moral property of women: a history of birth control politics in America. University of Illinois Press. pp. 295–296. ISBN 9780252027642.

- ^ a b Cook, Rebecca J. (1996). "Advancing Reproductive Rights Beyond Cairo and Beijing". International Family Planning Perspectives. 22 (3). Guttmacher Institute: 115–121. doi:10.2307/2950752. Retrieved 2007-12-08.

{{cite journal}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Freedman, Lynn P. (1993). "Human Rights and Reproductive Choice". Studies in Family Planning. 24 (1). Population Council: 18–30. doi:10.2307/2939211. Retrieved 2007-12-08.

{{cite journal}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Amnesty International USA (2007). "Stop Violence Against Women: Reproductive rights". SVAW. Amnesty International USA. Retrieved 2007-12-08.

- ^ [2]

- ^ Anika Rahman, Laura Katzive and Stanley K. Henshaw. A Global Review of Laws on Induced Abortion, 1985–1997, International Family Planning Perspectives (Volume 24, Number 2, June 1998).

- ^ a b [3]

- ^ [4]

- ^ [5]

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church 2271.

- ^ "UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Division for the Advancement of Women".

- ^ "Short History of the Commission on the Status of Women" (PDF).

- ^ Catagay, N., Grown, C. and Santiago, A. 1986. "The Nairobi Women's Conference: Toward a Global Feminism?" Feminist Studies, 12, 2:401–412

- ^ "Fourth World Conference on Women. Beijing, China. September 1995. Action for Equality, Development and Peace".

- ^ United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women: Introduction

- ^ a b c Morey, Dr Robert A. (2010). The Bible, Natural theology and Natural Law: Conflict Or Compromise?. Xulon Press. p. 282. ISBN 9781609571436.

- ^ a b Morey, Dr Robert A. (2010). The Bible, Natural theology and Natural Law: Conflict Or Compromise?. Xulon Press. p. 297. ISBN 9781609571436.

- ^ Morey, Dr Robert A. (2010). The Bible, Natural theology and Natural Law: Conflict Or Compromise?. Xulon Press. p. 214. ISBN 9781609571436.

- ^ a b Morey, Dr Robert A. (2010). The Bible, Natural theology and Natural Law: Conflict Or Compromise?. Xulon Press. p. 212. ISBN 9781609571436.

- ^ "Universal Declaration of Human Rights".

- ^ Member states

- ^ African Union: Rights of Women Protocol Adopted, press release, Amnesty International, 22 July 2003

- ^ UNICEF: toward ending female genital mutilation, press release, UNICEF, 7 February 2006

- ^ The Maputo Protocol of the African Union, brochure produced by GTZ for the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development

- ^ Fourth Annual Report of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda to the General Assembly (September, 1999), accessed at [6].

- ^ Navanethem Pillay is quoted by Professor Paul Walters in his presentation of her honorary doctorate of law, Rhodes University, April 2005 [7]

- ^ Violence Against Women: Worldwide Statistics

- ^ As quoted by Guy Horton in Dying Alive – A Legal Assessment of Human Rights Violations in Burma April 2005, co-Funded by The Netherlands Ministry for Development Co-Operation. See section "12.52 Crimes against humanity", Page 201. He references RSICC/C, Vol. 1 p. 360

- ^ Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court

- ^ Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action, Section II, paragraph 38

- ^ a b Rape as a Crime Against Humanity

- ^ a b Bosnia and Herzegovina : Foca verdict – rape and sexual enslavement are crimes against humanity. 22 February 2001. Amnesty International.

Sources

- Blundell, Sue (1995). Women in ancient Greec, Volume 2. Harvard University Press. p. 224. ISBN 0674954734, 9780674954731.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pomeroy, Sarah B. (2002), Spartan Women, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0195130676

{{citation}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help)