Right to property: Difference between revisions

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

=== John Lock and the American and French Revolution === |

=== John Lock and the American and French Revolution === |

||

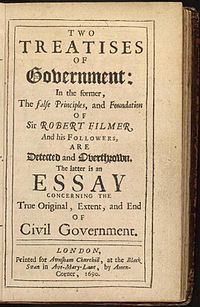

[[Image:Locke treatises of government page.jpg|200px|right|[[John Lock']]s 1689 [[Two Treatises of Government]], in it Locke calles "lives, liberties and estates" the "property" of individuals.]] |

|||

The revolutionary ideas on property and [[civil and political rights]] were further developed by the English philosopher [[John Locke]] (1632 – 1704). In [[Second Treatise on Civil Government]] (1689) Locke proclaimed that "everyman has a property in his person; this nobody has a right to but himself. The labor of his body and the work of his hand, we may say, are properly his". He argued that property ownership derives from ones labor, though those who do not own property and only have their labor to sell should not be given the same political power as those who owned property. Labourers, small scale property owners and large scale property owners should have civil and political rights in proportion to the property they owned. According to Locke the right to property and the right to life were inalienable rights, and that it was the duty of the State to secure these rights for individuals. Lock argued that the safeguarding of natural rights, such as the right to property, along with the separation of powers and other check and balances, would help to curtail political abuses by the state.<ref>{{Cite book| last = Rossides | first = Dabiel W.| title = Social Theory: Its Origins, History, and Contemporary Relevance| publisher = Rowman & Littlefield| date = 1998| pages = 52-54| url = http://books.google.com/books?id=TTYAGD7aKBkC&dq=levellers+property&source=gbs_navlinks_s| isbn = 9781882289509 }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book| last = Ishay| first = Micheline| title = The History of Human Rights: From Ancient Times to the Globalized Era| publisher = University of California Press| date = 2008| pages =91-94 | url = http://books.google.com/books?id=YTh22XQrtlQC&dq=right+to+property+human+rights&source=gbs_navlinks_s| isbn = 9780520256415}}</ref> |

The revolutionary ideas on property and [[civil and political rights]] were further developed by the English philosopher [[John Locke]] (1632 – 1704). In [[Second Treatise on Civil Government]] (1689) Locke proclaimed that "everyman has a property in his person; this nobody has a right to but himself. The labor of his body and the work of his hand, we may say, are properly his". He argued that property ownership derives from ones labor, though those who do not own property and only have their labor to sell should not be given the same political power as those who owned property. Labourers, small scale property owners and large scale property owners should have civil and political rights in proportion to the property they owned. According to Locke the right to property and the right to life were inalienable rights, and that it was the duty of the State to secure these rights for individuals. Lock argued that the safeguarding of natural rights, such as the right to property, along with the separation of powers and other check and balances, would help to curtail political abuses by the state.<ref>{{Cite book| last = Rossides | first = Dabiel W.| title = Social Theory: Its Origins, History, and Contemporary Relevance| publisher = Rowman & Littlefield| date = 1998| pages = 52-54| url = http://books.google.com/books?id=TTYAGD7aKBkC&dq=levellers+property&source=gbs_navlinks_s| isbn = 9781882289509 }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book| last = Ishay| first = Micheline| title = The History of Human Rights: From Ancient Times to the Globalized Era| publisher = University of California Press| date = 2008| pages =91-94 | url = http://books.google.com/books?id=YTh22XQrtlQC&dq=right+to+property+human+rights&source=gbs_navlinks_s| isbn = 9780520256415}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 18:01, 25 December 2010

The right to property, also known as the right to protection of property, is a human right and is understood to establish an entitlement to private property. The right to property is not absolute and states have a wide degree of discretion to limit the rights.

The right to property is enshrined in Article 17 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 14 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights and Article 1 of Protocol I of the European Convention on Human Rights. The right to property is not recognised in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights or the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.[1]

Definition

The right to property is one of the most controversial human rights, both in terms of its existence and interpretation. The controversy about the definition of the right meant that it was not included in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights or the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. The legal development of the right to property as a human rights occurs principally through the European Court of Human Rights in relation to Article 1 of Protocol I of the European Convention on Human Rights, where the right to protection of property is defined as:[2]

Every natural or legal person is entitled to the peaceful enjoyment of his possessions. No one shall be deprived of his possessions except in the public interest and subject to the conditions provided for by law and by the general principles of international law.

The preceding provisions shall not, however, in any way impair the right of a State to enforce such laws as it deems necessary to control the use of property in accordance with the general interest or to secure the payment of taxes or other contributions or penalties.[3]

The European Court of Human Rights has held that the right to property is not absolute and states have a wide degree of discretion to limit the rights. As such the right to property is regarded as a more flexible right than other human rights. States' degree of discretion is defined in Handyside v. United Kingdom, heard by the European Court of Human Rights in 1976. Notable cases where the European Court of Human Rights has found the right to property having been violated include Sporrong and Lonnroth v. Sweden, heard in 1982, where Swedish law kept property under the threat of expropriation for an extended period of time.[4]

History

In Europe the notion of private property and property rights emerged in the Renaissance as overseas trade by merchants gave rise to merchantilist ideas. In 16th Century Europe Lutheranism and the Protestant Reformation advanced property rights using biblical terminology. Protestant work ethic and views on man's destiny came to underline social view in emerging capitalist economies in Early modern Europe. The right to private property emerged as a radical demand for human rights vis-a-vis the state in the 17th Century revolutionary Europe. But in the 18th and 19th Century the right to property as a human right became subject of intense controversy.[5]

The English Civil War

The arguments advanced by the Levellers during the early English Civil War on property and civil and political rights, such as the right to vote, informed subsequent debates in other countries. The Levellers emerged as a political movement in mid 17th Century England in the aftermath of the Protestant Reformation. They believed that property which had been earned as the fruit of one's labour was sacred under the Bible's commandment "thou shall not steal". As such they believed that the right to acquire property from one's work was sacred. Levellers views on the right to property, and the right not to be deprived of property as a civil and political right, were developed the pamphleteer Richard Overton.[6] In "An Arrow against all Tyrants" (1646) Overton argued that:

"To every individual in nature is given an individual property by nature not to be invaded or usurped by any. For everyone, as he is himself , so he has a self propertiety, else he could not be himself; and of this no second may presume to deprive of without manifest violation and affront to the very principles of nature of the rules of equity and justice between man and man. Mine and thine cannot be, except this. No man has power over my rights and liberties, and I over no man."[7]

The views of the Levellers, who enjoyed support amongst small scale property owners and craftsmen, were not shared by all revolutionary parties of the English Civil War. At the 1647 General Council Oliver Cromwell and Henry Ireton argued against equating the right to life with the right to property. They argued that doing so would establish the right to take anything that one may want, irrespective of the rights of others. The Leveller Thomas Rainborough responded, relying on Overton's arguments, that the Levellers required respect for others' natural rights. The definition of property, and whether it was acquired as the fruit of one's labour and as such a natural right, was subject to intense debate because property ownership was tied to the right to vote. Political freedom was at the time associated with property ownership and individual independence. Cromwell and Ireton maintained that only property in freehold land or chartered trading rights gave a man the right to vote. They argued that this type of property ownership constituted a "take in society", which entitles men to political power. In contrast Levellers argued that all men who are not servants, alms recipients or beggars, should be considered as property owners and be given voting rights. They believed that political freedom could only be secured by individuals, such as craftsmen, engaging in independent economic activity.[8][9]

Levellers were primarily concerned with the civil and political rights of small scale property owners and workers. In contrast the Diggers, a smaller revolutionary group led by Gerard Winstanley, focused on the rights of the rural poor who worked on landed property. The Diggers argued that private property was not consistent with justice and argued that the land that had been confiscated from the crown and church should be turned into communal land to be cultivated by the poor. According to the Diggers the right to vote should be extended to all and everybody had the right to an adequate standard of living. When the monarchy was restored in 1660 all confiscated land returned to the crown and church. The English Civil War led to the recognition of some property rights and the establishment of limited voting rights. Though the ideas of the Levellers on property and civil and political rights remained influential and were advanced in the subsequent 1680 Glorious Revolution.[10][11]

John Lock and the American and French Revolution

The revolutionary ideas on property and civil and political rights were further developed by the English philosopher John Locke (1632 – 1704). In Second Treatise on Civil Government (1689) Locke proclaimed that "everyman has a property in his person; this nobody has a right to but himself. The labor of his body and the work of his hand, we may say, are properly his". He argued that property ownership derives from ones labor, though those who do not own property and only have their labor to sell should not be given the same political power as those who owned property. Labourers, small scale property owners and large scale property owners should have civil and political rights in proportion to the property they owned. According to Locke the right to property and the right to life were inalienable rights, and that it was the duty of the State to secure these rights for individuals. Lock argued that the safeguarding of natural rights, such as the right to property, along with the separation of powers and other check and balances, would help to curtail political abuses by the state.[12][13]

Lock's arguments on property and the separation of power greatly influenced the American Revolution and the French Revolution. The entitlement to civil and political rights, such as the right to vote, was tied to the question of property in both revolutions. American Revolutionaries, such as Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson, opposed universal suffrage only fo rthose who owned a "stake" in society. James Madison argued that extending the right to vote to all could lead in the right to property and justice being "overruled by a majority without property". While it was initially suggested to establish the right to vote for all men, eventually the right to vote was extended to white men who owned a specified amount of real estate and personal property. French Revolutionaries recognised property rights in Article 7 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1791), which stated that no one "may be deprived of property rights unless a legally established public necessity required it and upon condition of a just and previous indemnity." In Article 3 and 6 the it was declared that "all citizens have the right to contribute personally or through their representatives" in the political system, and that "all citizens being equal before [the law], are equally admissible to all public offices, positions and employment according to their capacity, and without other distinction than that of virtues and talents". But in practice the French revolutionaries did not extended civil and political rights to all, although the property qualification required for such rights was lower than that established by the American revolutionaries.[14]

According to the French revolutionary Abbe Sieyes "all the inhabitants of a country should enjoy the right of a passive citizen... but those alone who contribute to the public establishment are like the true shareholders in the great social enterprise. They alone are the true active citizens, the true members of the association". Three months after the Declaration had been adopted domestic servants, women and those who did not pay taxes equal to three days of labor were declared "passive citizens". Sieyes wanted to see the rapid expansion of commercial activities and favoured the unrestricted accumulation of property. In contrast Maximilien Robespierre warned that the free accumulation of wealth ought to be limited and that the right to property should not be permitted to violate the rights of others, particularly poorer citizens, including the working poor and peasants. Robespierre's views were eventually excluded from the French Constitution of 1793 and property qualification for civil and political rights was maintained.[15]

See also

References

- ^ Doebbler, Curtis (2006). Introduction to International Human Rights Law. CD Publishing. pp. 141–142. ISBN 9780974357027.

- ^ Doebbler, Curtis (2006). Introduction to International Human Rights Law. CD Publishing. pp. 141–142. ISBN 9780974357027.

- ^ "Protocol I to the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms". Council of Europe. pp. Protocol 1 Article 1.

- ^ Doebbler, Curtis (2006). Introduction to International Human Rights Law. CD Publishing. pp. 141–142. ISBN 9780974357027.

- ^ Ishay, Micheline (2008). The History of Human Rights: From Ancient Times to the Globalized Era. University of California Press. p. 91. ISBN 9780520256415.

- ^ Ishay, Micheline (2008). The History of Human Rights: From Ancient Times to the Globalized Era. University of California Press. pp. 91–94. ISBN 9780520256415.

- ^ Ishay, Micheline (2008). The History of Human Rights: From Ancient Times to the Globalized Era. University of California Press. p. 92. ISBN 9780520256415.

- ^ Rossides, Dabiel W. (1998). Social Theory: Its Origins, History, and Contemporary Relevance. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 54. ISBN 9781882289509.

- ^ Ishay, Micheline (2008). The History of Human Rights: From Ancient Times to the Globalized Era. University of California Press. pp. 91–94. ISBN 9780520256415.

- ^ Rossides, Dabiel W. (1998). Social Theory: Its Origins, History, and Contemporary Relevance. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 54. ISBN 9781882289509.

- ^ Ishay, Micheline (2008). The History of Human Rights: From Ancient Times to the Globalized Era. University of California Press. pp. 91–94. ISBN 9780520256415.

- ^ Rossides, Dabiel W. (1998). Social Theory: Its Origins, History, and Contemporary Relevance. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 52–54. ISBN 9781882289509.

- ^ Ishay, Micheline (2008). The History of Human Rights: From Ancient Times to the Globalized Era. University of California Press. pp. 91–94. ISBN 9780520256415.

- ^ Ishay, Micheline (2008). The History of Human Rights: From Ancient Times to the Globalized Era. University of California Press. pp. 94–97. ISBN 9780520256415.

- ^ Ishay, Micheline (2008). The History of Human Rights: From Ancient Times to the Globalized Era. University of California Press. pp. 97–98. ISBN 9780520256415.

External links

Template:Articles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights