Kielce pogrom: Difference between revisions

copyedit |

copyedit, removed unsourced irrelevances |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Copyedit|date=December 2009}} |

|||

{{Infobox civilian attack |

{{Infobox civilian attack |

||

| title = Kielce pogrom |

| title = Kielce pogrom |

||

| Line 25: | Line 23: | ||

For these reasons debate about the origins of the pogrom has remained controversial. Some claim it was a deliberate provocation by the communists to discredit the nationalists. Some claim that it was an anti-semitic event that was later exploited by the Government. Others accuse the Polish [[Roman Catholic]] hierarchy of irresponsibility for intervening at too late a stage. The fact that a number of Jews [[Żydokomuna|held important positions in the Polish communist party]] also affected popular sentiment. The absence of clear documentary evidence complicates analysis.<ref>Kaminski (2006), 118-120</ref> |

For these reasons debate about the origins of the pogrom has remained controversial. Some claim it was a deliberate provocation by the communists to discredit the nationalists. Some claim that it was an anti-semitic event that was later exploited by the Government. Others accuse the Polish [[Roman Catholic]] hierarchy of irresponsibility for intervening at too late a stage. The fact that a number of Jews [[Żydokomuna|held important positions in the Polish communist party]] also affected popular sentiment. The absence of clear documentary evidence complicates analysis.<ref>Kaminski (2006), 118-120</ref> |

||

However, whilst far from the deadliest [[pogrom]] against the Jews, the incident was a significant point in the post-war history of Jews in Poland. The Kielce event took place only a year after the end |

However, whilst far from the deadliest [[pogrom]] against the Jews, the incident was a significant point in the post-war history of Jews in Poland. The Kielce event took place only a year after the end of World War II and the [[Holocaust]], shocking Jews in Poland, many Poles, as well as the international community. It has been considered a catalyst for the flight of most Jewish survivors from Poland. |

||

== The pogrom== |

== The pogrom== |

||

| Line 35: | Line 33: | ||

On July 1, 1946, an eight-year-old Polish boy, Henryk Błaszczyk, was reported missing by his father Walenty. Two days later, the boy, his father and one of their neighbours went to a local [[police station]] where Henryk falsely claimed that he had been kidnapped by Jews. Henryk accused the Jews of [[Blood libel against Jews|killing children for their blood]] and keeping the bodies in the cellar of the Jewish house on Planty Street. (He subsequently retrated this story, saying he had been "ordered to say it").<ref name="t">{{cite news | author=Times Correspondent | title=Anti-Jewish Riots in Poland | url=http://archive.timesonline.co.uk/tol/viewArticle.arc?articleId=ARCHIVE-The_Times-1946-07-06-04-002&pageId=ARCHIVE-The_Times-1946-07-06-04 | publisher=[[The Times]] | pages= 4 | date=6 July 1946 | accessdate=19 June 2009 }}</ref> |

On July 1, 1946, an eight-year-old Polish boy, Henryk Błaszczyk, was reported missing by his father Walenty. Two days later, the boy, his father and one of their neighbours went to a local [[police station]] where Henryk falsely claimed that he had been kidnapped by Jews. Henryk accused the Jews of [[Blood libel against Jews|killing children for their blood]] and keeping the bodies in the cellar of the Jewish house on Planty Street. (He subsequently retrated this story, saying he had been "ordered to say it").<ref name="t">{{cite news | author=Times Correspondent | title=Anti-Jewish Riots in Poland | url=http://archive.timesonline.co.uk/tol/viewArticle.arc?articleId=ARCHIVE-The_Times-1946-07-06-04-002&pageId=ARCHIVE-The_Times-1946-07-06-04 | publisher=[[The Times]] | pages= 4 | date=6 July 1946 | accessdate=19 June 2009 }}</ref> |

||

A patrol of 14 uniformed and plainclothed MO officers was dispatched on foot to the Jewish house at Planty street by a new [[police chief]], Sergeant Edmund Zagórski. On their way, they spread rumours of the alleged [[kidnapping]], and were soon joined by about 100 servicemen from various military formations ([[Ludowe Wojsko Polskie|LWP]], [[Internal Security Corps|KBW]], [[Main Directorate of Information of the Polish Army|GZI]]) and police. The false accusations of the Jewish religious atrocities spread among the non-Jewish civilians in Kielce, and resulted in a gathering outside the Jewish residence in anticipation of a search for |

A patrol of 14 uniformed and plainclothed MO officers was dispatched on foot to the Jewish house at Planty street by a new [[police chief]], Sergeant Edmund Zagórski. On their way, they spread rumours of the alleged [[kidnapping]], and were soon joined by about 100 servicemen from various State military formations ([[Ludowe Wojsko Polskie|LWP]], [[Internal Security Corps|KBW]], [[Main Directorate of Information of the Polish Army|GZI]]) and police. The false accusations of the Jewish religious atrocities spread among the non-Jewish civilians in Kielce, and resulted in a gathering outside the Jewish residence in anticipation of a search for bodies of [[Christianity|Christian]] children alleged to be buried there. |

||

By 9:00 a.m., uniformed policemen and soldiers, as well as several mostly plainclothed security officers, broke down the doors and entered the building. They began to disarm the inhabitants, who had permits from the authorities to bear arms for [[self defense]]. One Jewish man (described by Henryk) was arrested and beaten by the police, while Dr. Seweryn Kahane, the head of the local Jewish Committee, tried to convince them of their mistake, pointing out that the building had no basement |

By 9:00 a.m., uniformed policemen and soldiers, as well as several mostly plainclothed security officers, broke down the doors and entered the building. They began to disarm the inhabitants, who had permits from the authorities to bear arms for [[self defense]]. One Jewish man (described by Henryk) was arrested and beaten by the police, while Dr. Seweryn Kahane, the head of the local Jewish Committee, tried to convince them of their mistake, pointing out that the building had no basement. Soldiers detained some of the Jews and led them outside, where they were abused by members of the crowd. |

||

===Killings=== |

===Killings=== |

||

By 10:00 a.m., the first shot was fired; it is unclear by whom: a policeman, a soldier, or one of the armed Jews. Deadly violence broke out and the security forces began shooting Jews and beating them with rifle butts. Dr. Kahane was among the first to be killed (survivors testified that he was shot in the back of the head by an officer of the military intelligence while trying to call the authorities for help). There was also some shooting from the Jewish side; at least two and possibly three Poles, including a police officer, were killed as the Jews tried to defend themselves. After the initial killings inside the building, more Jews were then forced outside by the troops and then pelted with rocks and attacked with sticks by civilians in the street. |

By 10:00 a.m., the first shot was fired; it is unclear by whom: a policeman, a soldier, or one of the armed Jews. Deadly violence broke out and the security forces began shooting Jews and beating them with rifle butts. Dr. Kahane was among the first to be killed (survivors testified that he was shot in the back of the head by an officer of the military intelligence while trying to call the authorities for help). There was also some shooting from the Jewish side; at least two and possibly three Poles, including a police officer, were killed as the Jews tried to defend themselves. After the initial killings inside the building, more Jews were then forced outside by the troops and then pelted with rocks and attacked with sticks by civilians in the street. |

||

By noon, the arrival of a large group of estimated about 600 to 1,000 workers from the nearby [[Ludwików]] [[steel mill]], led by activists of the [[Polish Workers' Party|PPR]] (Poland's ruling [[communist party]]), marked the beginning of the next phase of the pogrom, during which about 20 Jews were beaten to death. Many of the workers were members of the ORMO (reserve formation of the MO), armed with steel rods and at least one pistol. Neither the military and secret police commanders, who included a [[Soviet Union|Soviet]] military advisor at the scene, nor the local political leaders from the PPR, did anything to stop the workers from attacking the Jews. A unit of police [[cadet]]s which arrived there did not intervene, and some of its members joined in the [[looting]] and murders of the Jews, which continued inside and outside the building. The mob also killed a Jewish nurse of "[[Aryan race|Aryan]]" appearance (Estera Proszowska), whom the attackers apparently mistaken for a Polish woman trying to aid the dying Jews.<ref name=rzepa/> |

By noon, the arrival of a large group of estimated about 600 to 1,000 workers from the nearby [[Ludwików]] [[steel mill]], led by activists of the [[Polish Workers' Party|PPR]] (Poland's ruling [[communist party]]), marked the beginning of the next phase of the pogrom, during which about 20 Jews were beaten to death. Many of the workers were members of the ORMO (reserve formation of the MO), armed with steel rods and at least one pistol. Neither the military and secret police commanders, who included a [[Soviet Union|Soviet]] military advisor at the scene, nor the local political leaders from the PPR, did anything to stop the workers from attacking the Jews. A unit of police [[cadet]]s which arrived there did not intervene, and some of its members joined in the [[looting]] and murders of the Jews, which continued inside and outside the building. The mob also killed a Jewish nurse of "[[Aryan race|Aryan]]" appearance (Estera Proszowska), whom the attackers apparently mistaken for a Polish woman trying to aid the dying Jews.<ref name=rzepa/> |

||

| Line 52: | Line 50: | ||

==The aftermath== |

==The aftermath== |

||

===Official reaction of the government and resulting trials=== |

===Official reaction of the government and resulting trials=== |

||

Between July 9 and July 11, 1946, 12 of the alleged civilian perpetrators of the pogrom, one of them apparently mentally challenged, were arrested by MBP officers led by |

Between July 9 and July 11, 1946, 12 of the alleged civilian perpetrators of the pogrom, one of them apparently mentally challenged, were arrested by MBP officers led by and were tried by the Supreme [[Military Court]] in a joint [[show trial]]. Nine of the accused were sentenced to death and the very next day executed by [[firing squad]] on the orders of the Polish communist leader [[Bolesław Bierut]]. The remaining three received prison terms ranging from seven years to life. |

||

Other than the Kielce MO commandant Wiktor Kuźnicki, who was sentenced to one year for "failing to stop the crowd" (he died in 1947), one police officer was punished—for the theft of shoes from a dead body. Mazur's explanation regarding his killing of the Fisz family was also accepted. Meanwhile, the regional UBP chief Władysław Sobczyński and his men were all cleared of any wrongdoing. The official reaction to the pogrom was described by [[Anita J. Prazmowska]] in ''Cold War History'', Vol. 2, No. 2: |

Other than the Kielce MO commandant Wiktor Kuźnicki, who was sentenced to one year for "failing to stop the crowd" (he died in 1947), one police officer was punished—for the theft of shoes from a dead body. Mazur's explanation regarding his killing of the Fisz family was also accepted. Meanwhile, the regional UBP chief Władysław Sobczyński and his men were all cleared of any wrongdoing. The official reaction to the pogrom was described by [[Anita J. Prazmowska]] in ''Cold War History'', Vol. 2, No. 2: |

||

<blockquote>Nine participants in the pogrom were sentenced to death; three were given lengthy prison sentences. Policemen, military men, and functionaries of the UBP were tried separately and then unexpectedly all, with the exception of Wiktor Kuznicki, Commander of the MO, who was sentenced to one year in prison, were found not guilty of "having taken no action to stop the crowd from committing crimes." Clearly, during the period when the first investigations were launched and the trial, a most likely politically motivated decision had been made not to proceed with disciplinary action. This was in spite of very disturbing evidence that emerged during the pre-trial interviews. It is entirely feasible that instructions not to punish the MO and UBP commanders had been given because of the politically sensitive nature of the evidence. Evidence heard by the military prosecutor revealed major organizational and ideological weaknesses within these two security services...<ref name="Prazmowska">{{cite book | author =Anita Prażmowska | coauthors = | title =Poland's Century: War, Communism and Anti-Semitism | year =2002 | editor = | pages = | chapter =Case Study: The Pogrom in Kielce | chapterurl =http://www.fathom.com/course/72809602/session3.html | publisher =London School of Economics and Political Science | location =London | id = | url = | format = | accessdate = }}</ref> |

|||

</blockquote> |

|||

===Effects on Jewish emigration from Poland=== |

===Effects on Jewish emigration from Poland=== |

||

The brutality of the Kielce pogrom put an end to the hopes of many Jews that they would be able to resettle in Poland after the end of the [[Nazi Germany]] occupation and precipitated a mass exodus of Polish Jewry.<ref>Abraham Duker. [http://books.google.com/books?id=7MTa8eoig4kC&pg=PA252&dq=Michael+Checinski++kielce&ei=0q4XSZ6MHJbQzATR0u37CQ#PPA233,M1 Twentieth century blood libels in the United States.] In: Alan Dundes. The Blood Libel Legend: A Casebook in Anti-Semitic Folklore. University of Wisconsin Press, 1991.</ref> In the words of Bożena Szaynok, a historian at [[Wrocław University]]: |

The brutality of the Kielce pogrom put an end to the hopes of many Jews that they would be able to resettle in Poland after the end of the [[Nazi Germany]] occupation and precipitated a mass exodus of Polish Jewry.<ref>Abraham Duker. [http://books.google.com/books?id=7MTa8eoig4kC&pg=PA252&dq=Michael+Checinski++kielce&ei=0q4XSZ6MHJbQzATR0u37CQ#PPA233,M1 Twentieth century blood libels in the United States.] In: Alan Dundes. The Blood Libel Legend: A Casebook in Anti-Semitic Folklore. University of Wisconsin Press, 1991.</ref> In the words of Bożena Szaynok, a historian at [[Wrocław University]]: |

||

| Line 69: | Line 67: | ||

===Reaction of the Catholic Church=== |

===Reaction of the Catholic Church=== |

||

Six months prior to the Kielce pogrom, during the [[Hanukkah]] celebration, a [[hand grenade]] had been thrown into the local Jewish community headquarters. The Jewish Community Council had approached the [[Bishop]] of Kielce, Czesław Kaczmarek, requesting him to admonish the Polish population to refrain from attacking the Jews. The Bishop refused this request, replying that "as long as the Jews concentrated upon their private business Poland was interested in them, but at the point when Jews began to interfere in Polish politics and public life they insulted the Poles’ national sensibilities". Therefore, according to the Bishop, it was not surprising that the local population had acted violently.<ref>[http://www1.yadvashem.org/about_holocaust/studies/vol33/AleksiunEngPrint3.pdf The Roman Catholic Church and the Jewish Question in Poland, 1944-1948<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

Six months prior to the Kielce pogrom, during the [[Hanukkah]] celebration, a [[hand grenade]] had been thrown into the local Jewish community headquarters. The Jewish Community Council had approached the [[Bishop]] of Kielce, Czesław Kaczmarek, requesting him to admonish the Polish population to refrain from attacking the Jews. The Bishop refused this request, replying that "as long as the Jews concentrated upon their private business Poland was interested in them, but at the point when Jews began to interfere in Polish politics and public life they insulted the Poles’ national sensibilities". Therefore, according to the Bishop, it was not surprising that the local population had acted violently.<ref>[http://www1.yadvashem.org/about_holocaust/studies/vol33/AleksiunEngPrint3.pdf The Roman Catholic Church and the Jewish Question in Poland, 1944-1948<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

||

| Line 78: | Line 75: | ||

On September 14, 1946, [[Pope Pius XII]] gave an audience to [[Rabbi]] Phillip Bernstein, the advisor on Jewish affairs to the U.S. [[European theater of operations]]. Bernstein asked the [[Pope]] to condemn the pogroms, but the Pope claimed that it was difficult to communicate with the Church in Poland because of the [[Iron Curtain]].<ref>[http://www.davidsconsultants.com/jewishhistory/history.php?startyear=1940&endyear=1949 Jewish History Day by Day]</ref> |

On September 14, 1946, [[Pope Pius XII]] gave an audience to [[Rabbi]] Phillip Bernstein, the advisor on Jewish affairs to the U.S. [[European theater of operations]]. Bernstein asked the [[Pope]] to condemn the pogroms, but the Pope claimed that it was difficult to communicate with the Church in Poland because of the [[Iron Curtain]].<ref>[http://www.davidsconsultants.com/jewishhistory/history.php?startyear=1940&endyear=1949 Jewish History Day by Day]</ref> |

||

==Speculations over Soviet involvement== |

==Speculations over Communist and/or Soviet involvement== |

||

The Kielce pogrom has been a difficult subject in Polish history for many years, and there is still confusion over whom to blame. While it is beyond doubt that a mob (consisting of some gentile inhabitants of Kielce including members of the communist ''[[militsiya]]'' police and army), carried out the pogrom, there has been considerable controversy over possible outside inspiration for the events. The hypothesis that the event was [[Provocation (legal)|provoked]], or inspired, by [[Soviet intelligence]] has been put forward, and a number of similar scenarios are offered. |

The Kielce pogrom has been a difficult subject in Polish history for many years, and there is still confusion over whom to blame. While it is beyond doubt that a mob (consisting of some gentile inhabitants of Kielce including members of the communist ''[[militsiya]]'' police and army), carried out the pogrom, there has been considerable controversy over possible outside inspiration for the events. The hypothesis that the event was [[Provocation (legal)|provoked]], or inspired, by [[Soviet intelligence]] has been put forward, and a number of similar scenarios are offered. |

||

Revision as of 18:30, 14 January 2010

| Kielce pogrom | |

|---|---|

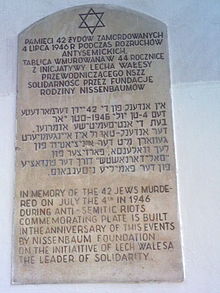

Memorial plaque at the 7 Planty Street, Kielce dedicated by Lech Wałęsa in 1990 | |

| Location | Kielce, Poland |

| Date | July 4, 1946 |

| Target | Primarily Jews |

| Deaths | 42 |

The Kielce pogrom was an outbreak of violence against the Jewish community of Kielce, Poland on July 4, 1946. It was perpetrated by a mob of local townsfolk, including police[1] and soldiers. Folowing a false tale of child kidnapping, including allegations of blood libel[2] which led to a police investigation, violence broke out which resulted in 42[3] Polish Jews being murdered and 40 more injured, out of about 200 Holocaust survivors who after the war had returned to the town from German Nazi concentration camps and elsewhere.

Polish courts tried and condemned nine people to death for their crimes who were later executed. Thecommunist government of Poland sought to lay blame on Polish nationalists, especially the anti-communist partisans backing Colonel Anders and the Polish government-in-exile. [4]. Further investgation into the circumstances of the pogrom were inhibited by the communist government until the era of Solidarnosc, when in 1981 an article was published in the newspaper Solidarity Weekly.[5] However the return of repressive government meant that files could not be accessed for historical research until after the fall of communism in 1989. It was then discovered that many documents relating to the pogrom had been destroyed by fire (in unclear circumstances) or deliberately by military authorities.[6]

For these reasons debate about the origins of the pogrom has remained controversial. Some claim it was a deliberate provocation by the communists to discredit the nationalists. Some claim that it was an anti-semitic event that was later exploited by the Government. Others accuse the Polish Roman Catholic hierarchy of irresponsibility for intervening at too late a stage. The fact that a number of Jews held important positions in the Polish communist party also affected popular sentiment. The absence of clear documentary evidence complicates analysis.[7]

However, whilst far from the deadliest pogrom against the Jews, the incident was a significant point in the post-war history of Jews in Poland. The Kielce event took place only a year after the end of World War II and the Holocaust, shocking Jews in Poland, many Poles, as well as the international community. It has been considered a catalyst for the flight of most Jewish survivors from Poland.

The pogrom

Background

During the German occupation of Poland, Kielce was entirely ethnically cleansed by the Nazis of its pre war Jewish population. By the summer of 1946, some 200 Jews, many of them former residents of Kielce, were living there after returning from the Nazi concentration camps and from elsewhere. About 150-160 of them were quartered in a single building administered by the Jewish Committee of Kielce Voivodeship at 7 Planty Street,[8] a small street in the centre of the town.

On July 1, 1946, an eight-year-old Polish boy, Henryk Błaszczyk, was reported missing by his father Walenty. Two days later, the boy, his father and one of their neighbours went to a local police station where Henryk falsely claimed that he had been kidnapped by Jews. Henryk accused the Jews of killing children for their blood and keeping the bodies in the cellar of the Jewish house on Planty Street. (He subsequently retrated this story, saying he had been "ordered to say it").[2]

A patrol of 14 uniformed and plainclothed MO officers was dispatched on foot to the Jewish house at Planty street by a new police chief, Sergeant Edmund Zagórski. On their way, they spread rumours of the alleged kidnapping, and were soon joined by about 100 servicemen from various State military formations (LWP, KBW, GZI) and police. The false accusations of the Jewish religious atrocities spread among the non-Jewish civilians in Kielce, and resulted in a gathering outside the Jewish residence in anticipation of a search for bodies of Christian children alleged to be buried there.

By 9:00 a.m., uniformed policemen and soldiers, as well as several mostly plainclothed security officers, broke down the doors and entered the building. They began to disarm the inhabitants, who had permits from the authorities to bear arms for self defense. One Jewish man (described by Henryk) was arrested and beaten by the police, while Dr. Seweryn Kahane, the head of the local Jewish Committee, tried to convince them of their mistake, pointing out that the building had no basement. Soldiers detained some of the Jews and led them outside, where they were abused by members of the crowd.

Killings

By 10:00 a.m., the first shot was fired; it is unclear by whom: a policeman, a soldier, or one of the armed Jews. Deadly violence broke out and the security forces began shooting Jews and beating them with rifle butts. Dr. Kahane was among the first to be killed (survivors testified that he was shot in the back of the head by an officer of the military intelligence while trying to call the authorities for help). There was also some shooting from the Jewish side; at least two and possibly three Poles, including a police officer, were killed as the Jews tried to defend themselves. After the initial killings inside the building, more Jews were then forced outside by the troops and then pelted with rocks and attacked with sticks by civilians in the street.

By noon, the arrival of a large group of estimated about 600 to 1,000 workers from the nearby Ludwików steel mill, led by activists of the PPR (Poland's ruling communist party), marked the beginning of the next phase of the pogrom, during which about 20 Jews were beaten to death. Many of the workers were members of the ORMO (reserve formation of the MO), armed with steel rods and at least one pistol. Neither the military and secret police commanders, who included a Soviet military advisor at the scene, nor the local political leaders from the PPR, did anything to stop the workers from attacking the Jews. A unit of police cadets which arrived there did not intervene, and some of its members joined in the looting and murders of the Jews, which continued inside and outside the building. The mob also killed a Jewish nurse of "Aryan" appearance (Estera Proszowska), whom the attackers apparently mistaken for a Polish woman trying to aid the dying Jews.[9]

The killing of the Jews at Planty Street was eventually stopped at approximately 6:00 p.m with the arrival of a new unit of security forces from a nearby Public Security academy sent by Colonel Stanisław Kupsza and additional troops from Warsaw. After firing a few warning shots in the air on the order of Major Kazimierz Konieczny, the new troops quickly restored order, posted guards, and removed all the Jewish survivors and dead bodies from the building. The violence in Kielce, however, did not stop immediately. Wounded Jews, while being transported to the hospital, were beaten and robbed by soldiers.[10] Trains passing through Kielce's main railway station were searched for Jews by civilians and the SOK railway guards, resulting in at least two passengers being thrown out of the trains and killed. (As many as 30 people may have been killed in this manner, as the train murders continued for several months after the pogrom.[9]) Later, a civilian crowd approached the hospital and unsuccessfully demanded that the wounded Jews be handed over to them (the hospital staff refused). The large-scale disorder in Kielce ultimately ended some nine hours after it started.

Among the 42 murdered Jews, including women and children, nine were shot dead, two were killed with bayonets, and the rest were beaten or stoned to death. In addition to the victims of the train violence, two Jews who didn't live at Planty Street were also murdered (Regina Fisz and her three-week-old son Abram were seized at their home at 15 Leonarda Street by a group of police led by Stefan Mazur, who robbed their victims and drove them out of the city; there, Regina and her baby were shot "while trying to escape"). Among the dead were also three Poles, all of them security servicemen. Two of them (uniformed) were killed by gunfire, apparently by the Jews who were not yet disarmed; the cause of death of third (plain-clothed) was not disclosed.[9]

Julia Pirotte, a well-known photojournalist of the French Resistance, photographed the pogrom's immediate aftermath.[11]

The aftermath

Official reaction of the government and resulting trials

Between July 9 and July 11, 1946, 12 of the alleged civilian perpetrators of the pogrom, one of them apparently mentally challenged, were arrested by MBP officers led by and were tried by the Supreme Military Court in a joint show trial. Nine of the accused were sentenced to death and the very next day executed by firing squad on the orders of the Polish communist leader Bolesław Bierut. The remaining three received prison terms ranging from seven years to life.

Other than the Kielce MO commandant Wiktor Kuźnicki, who was sentenced to one year for "failing to stop the crowd" (he died in 1947), one police officer was punished—for the theft of shoes from a dead body. Mazur's explanation regarding his killing of the Fisz family was also accepted. Meanwhile, the regional UBP chief Władysław Sobczyński and his men were all cleared of any wrongdoing. The official reaction to the pogrom was described by Anita J. Prazmowska in Cold War History, Vol. 2, No. 2:

Nine participants in the pogrom were sentenced to death; three were given lengthy prison sentences. Policemen, military men, and functionaries of the UBP were tried separately and then unexpectedly all, with the exception of Wiktor Kuznicki, Commander of the MO, who was sentenced to one year in prison, were found not guilty of "having taken no action to stop the crowd from committing crimes." Clearly, during the period when the first investigations were launched and the trial, a most likely politically motivated decision had been made not to proceed with disciplinary action. This was in spite of very disturbing evidence that emerged during the pre-trial interviews. It is entirely feasible that instructions not to punish the MO and UBP commanders had been given because of the politically sensitive nature of the evidence. Evidence heard by the military prosecutor revealed major organizational and ideological weaknesses within these two security services...[12]

Effects on Jewish emigration from Poland

The brutality of the Kielce pogrom put an end to the hopes of many Jews that they would be able to resettle in Poland after the end of the Nazi Germany occupation and precipitated a mass exodus of Polish Jewry.[13] In the words of Bożena Szaynok, a historian at Wrocław University:

- "Until 4 July 1946, Polish Jews cited the past as their main reason for emigration. After the Kielce pogrom, the situation changed drastically. Both Jewish and Polish reports spoke of an atmosphere of panic among Jewish society in the summer of 1946. Jews no longer believed that they could be safe in Poland. Despite the large militia and army presence in the town of Kielce, Jews had been murdered there in cold blood, in public, and for a period of more than five hours. The news that the militia and the army had taken part in the pogrom spread as well. From July 1945 until June 1946, about fifty thousand Jews passed the Polish border illegally. In July 1946, almost twenty thousand decided to leave Poland. In August 1946 the number increased to thirty thousand. In September 1946, twelve thousand Jews left Poland."[10]

Many of these Jews were smuggled out illegally by the Berihah (Escape) organization.

Reaction of the Catholic Church

Six months prior to the Kielce pogrom, during the Hanukkah celebration, a hand grenade had been thrown into the local Jewish community headquarters. The Jewish Community Council had approached the Bishop of Kielce, Czesław Kaczmarek, requesting him to admonish the Polish population to refrain from attacking the Jews. The Bishop refused this request, replying that "as long as the Jews concentrated upon their private business Poland was interested in them, but at the point when Jews began to interfere in Polish politics and public life they insulted the Poles’ national sensibilities". Therefore, according to the Bishop, it was not surprising that the local population had acted violently.[14]

Similar comments were made by the Bishop of Lublin, Stefan Wyszyński, when he was approached by a Jewish delegation. Wyszyński stated that the popular hatred of Jews was caused by Jewish support for communism (there was widespread perception in Poland after 1945 that Jews were supportive of the newly installed communist regime; see Żydokomuna), which had also been the reason why "the Germans murdered the Jewish nation". Wyszyński also gave some credence to blood libel rumours commenting that the question of the use of Christian blood was never completely clarified.[15]

The controversial stance of the Roman Catholic Church towards anti-Jewish violence was the subject of criticism by American, British, and Italian ambassadors to Poland. Reports of the Kielce pogrom caused a major sensation in the United States, leading the American ambassador to Poland to insist that Cardinal August Hlond hold a press conference and explain the position of the church. In the conference held on July 11, 1946, Cardinal Hlond condemned the murders, but attributed them not to racial causes but to rumours concerning the killing of Polish children by Jews. Hlond also put the blame for the deterioration in Polish-Jewish relations on the Jews "occupying leading positions in Poland in state life". This position was echoed by Cardinal Adam Stefan Sapieha, who was reported to have said that the Jews had brought it on themselves, and by Polish rural clergy.[16]

On September 14, 1946, Pope Pius XII gave an audience to Rabbi Phillip Bernstein, the advisor on Jewish affairs to the U.S. European theater of operations. Bernstein asked the Pope to condemn the pogroms, but the Pope claimed that it was difficult to communicate with the Church in Poland because of the Iron Curtain.[17]

Speculations over Communist and/or Soviet involvement

The Kielce pogrom has been a difficult subject in Polish history for many years, and there is still confusion over whom to blame. While it is beyond doubt that a mob (consisting of some gentile inhabitants of Kielce including members of the communist militsiya police and army), carried out the pogrom, there has been considerable controversy over possible outside inspiration for the events. The hypothesis that the event was provoked, or inspired, by Soviet intelligence has been put forward, and a number of similar scenarios are offered.

Tadeusz Piotrowski,[18] logician Abel Kainer (Stanisław Krajewski),[19] and Jan Śledzianowski,[20] allegations are made that the events were part of a much wider action organized by Soviet intelligence in countries controlled by the Soviet Union (a very similar pogrom took place in Hungary), and that Soviet-dominated agencies like the UBP were used in the preparation of the Kielce pogrom. The presence in the city of Polish communist and Soviet commanders (e.g. the "advisor" Natan Shpilevoi (Szpilevoy) and a high-ranking GRU officer for special actions Mikhail Diomin) during the pogrom was confirmed by witnesses. It was also uncommon behavior that numerous troops from security formations were present at the place and did not prevent the "mob" from gathering, at a time when even a gathering of five people was considered suspicious and immediately controlled.[21]

Michael Checinski, a former Polish Military Counter-Intelligence officer, emigrated to United States after the 1968 Polish political crisis where he published his book in which asserts that the events of Kielce pogrom were a well planned action of the Soviet intelligence in Poland, with the main role in planning and controlling the events being played by Mikhail Diomin, and with the murders carried out by some Poles, including Polish policemen and military officers.[22][23]

On July 19, 1946, former Chief Military Prosecutor Henryk Holder wrote in the letter to the deputy chief of LWP Gen. Marian Spychalski that "we know that the pogrom wasn't only a fault of Militia and Army guarding the people in and around the city of Kielce but also members of the official government who took a role in it."[24]

One line of argument that implies external inspiration goes as follows:[25] The 1946 referendum showed that the communist plans met with little support, with less than a third of the Polish population, and only vote rigging won them a majority in the carefully controlled poll. Hence, it has been alleged that the UBP organized the pogrom to distract the Western world media's attention from the fabricated referendum. Another argument for the incident's use as distraction was the upcoming ruling on the Katyn massacre in the Nuremberg Trials, which the communists tried to turn international attention away from, placing the Poles in an unfavorable spotlight (the pogrom happened on July 4—the same day the Katyn case started in Nuremberg).

However Jan T. Gross attribues the massacre to what he describes as Polish hostility towards the Jews.[26] Gross' book, Fear: Anti-Semitism in Poland after Auschwitz, offers a somewhat different and more nuanced interpretation. Gross, while agreeing that the crime was initiated not by a mob, but by the communist police, and that it involved people from every walk of life except the highest level of government officials in the city,[27] says that the indifference of the majority of Poles to the Jewish Holocaust combined with demands for the return of Jewish property confiscated during World War II created a climate of "fear" that pushed Poles to commit violence against Jews. He thus argues against the notion that the pogrom was a Soviet provocation, or that the alleged cooperation of Jews with communism, an enduring and powerful stereotype of antisemitism in the Central Europe and particularly in Poland (popularly known in Polish as Żydokomuna, or "Judeocommunism"), caused the violent antisemitism that exploded in Poland after 1945. At the same time, Polish communist structures had already been in great part "cleansed" of Jews, even before the war, by the same people who later participated in the antisemitic events in Kielce (Władysław Sobczyński) and the antisemitic purges of 1968 (led by Mieczysław Moczar).[citation needed]

The opinion that the Soviets arranged the massacre in order to discredit the Poles in the eyes of the world remains common in Poland to this day, despite a thorough Polish investigation that did not discover any evidence in support of this version and the formal apology for the massacre that was issued by the Polish government. The standpoint that maintains foreign responsibility for such a disturbing event (similar to the version that the Germans rather than the Poles were responsible for the war-time Jedwabne pogrom) is ill-regarded by some Jewish groups who view it as evidence of the lack of determination in Polish society to confront and address antisemitism in Poland.[28]

Recent events

IPN investigation

In recent years, the Kielce pogrom and the role of Poles in the massacre have been openly discussed in Poland. A formal investigation of the pogrom conducted by the Polish Institute of National Remembrance (IPN) since 1990 finished inconclusively in 2004, as it did not find sufficient evidence to charge any specific living individual with crimes committed during the pogrom. However, the timeline of events on that fateful day is well established. In the course of the investigation, the IPN dismissed the theory of Soviet inspiration because of "lack of direct evidence and lack of obvious Soviet interest in provoking the events".[29]

Pogrom monument

A monument by New York-based artist Jack Sal entitled White/Wash II commemorating the victims was dedicated on July 4, 2006, in Kielce, on the 60th anniversary of the pogrom. At the dedication ceremony, a statement from the President of the Republic of Poland Lech Kaczyński condemned the events as a "crime and a great shame for the Poles and tragedy for the Polish Jews". The presidential statement asserted that in today's democratic Poland there is "no room for anti-Semitism" and brushed off any generalizations of the antisemitic image of the Polish nation as a "stereotype".[28]

See also

- Anti-Jewish violence in Poland, 1944-1946

- Białystok pogrom

- History of the Jews in Poland

- Kielce pogrom (1918)

- Kraków pogrom

References

- ^ http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Holocaust/Kielce.html

- ^ a b Times Correspondent (6 July 1946). "Anti-Jewish Riots in Poland". The Times. p. 4. Retrieved 19 June 2009.

- ^ http://www1.yadvashem.org.il/odot_pdf/Microsoft%20Word%20-%203128.pdf

- ^ Kaminski (2006), 26-78, passim

- ^ Kaminski (2006), 123

- ^ Kaminski (2006), 123-124

- ^ Kaminski (2006), 118-120

- ^ The Kielce Pogrom By Anna Williams

- ^ a b c Pogrom na Plantach, Rzeczpospolita, 01.07.2006

- ^ a b Bożena Szaynok. "The Jewish Pogrom in Kielce, July 1946 - New Evidence". Intermarium. 1 (3).

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ Julia Pirotte's photographs from the aftermath of the massacre are available online at Yad Vashem. Search for "Pirotte" in the Photo Archive.

- ^ Anita Prażmowska (2002). "Case Study: The Pogrom in Kielce". Poland's Century: War, Communism and Anti-Semitism. London: London School of Economics and Political Science.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Abraham Duker. Twentieth century blood libels in the United States. In: Alan Dundes. The Blood Libel Legend: A Casebook in Anti-Semitic Folklore. University of Wisconsin Press, 1991.

- ^ The Roman Catholic Church and the Jewish Question in Poland, 1944-1948

- ^ Eli Lederhendler (2005). Jews, Catholics, and the Burden of History. Oxford University Press. p. 37. ISBN 0195304918.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|chapterurl=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ Peter C. Kent (2002). The Lonely Cold War of Pope Pius XII: The Roman Catholic Church and the Division of Europe. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 128.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|chapterurl=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ Jewish History Day by Day

- ^ Tadeusz Piotrowski (sociologist) (1997). "Postwar years". Poland's Holocaust. McFarland & Company. p. 136. ISBN 0-7864-0371-3.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|chapterurl=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ Stanisław Krajewski (2004). "Jews and Communism". In Michael Bernhard, Henryk Szlajfer (ed.). From The Polish Underground. State College, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 380. ISBN 0-271-02565-4.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|chapterurl=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ Jan Śledzianowski in Pytania nad pogromem kieleckim, p. 213 Template:Pl icon

- ^ Krzysztof Kąkolewski (2006). Umarły cmentarz. Warszawa: Wydawn. von Borowiecky. ISBN 83-87689-73-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)Template:Pl icon - ^ Michael Checinski. Running the Gauntlet of Anti-Semitism. Devora Publishing, 2004.

- ^ Poland, Communism, Nationalism, Anti-semitism By Michael Checinski

- ^ Wokół pogromu, cyt. za: J. Śledzianowski, s. 80

- ^ Postanowienie o umorzeniu śledztwa w sprawie pogromu kieleckiego, prowadzonego przez OKŚZpNP w Krakowie, 21 October 2004, Kraków Template:Pl icon

- ^ Jan T. Gross, Postwar Anti-Semitism" in Revolution from Abroad: The Soviet Conquest of Poland's Western Ukraine and Western Belorussia, pp. 274-286

- ^ Fear, pp. 83-166

- ^ a b Matthew Day, 60 years on, Europe's last pogrom still casts dark shadow, The Scotsman, 5 July 2006.

- ^ Jacek Żurek, "Śledztwo IPN w sprawie pogromu kieleckiego i jego materiały (1991-2004)" in Wokół pogromu kieleckiego, p. 136

Sources

- Marek Jan Chodakiewicz (2003). After the Holocaust. East European Monographs. ISBN 0-88033-511-4.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|chapterurl=and|coauthors=(help) - Jan Śledzianowski (1998). Pytania nad pogromem kieleckim. Kielce: Jedność. ISBN 83-7224-057-4.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|chapterurl=and|coauthors=(help) - Łukasz Kamiński and Jan Żaryn (editors), Reflections on the Kielce Pogrom (articles by Bożena Szaynok, Ryszard Śmietanka-Kruszelnicki, Jan Żaryn and Jacek Żurek), Warsaw 2006 ISBN 8360464235

External links

- The Jewish Pogrom in Kielce, July 1946, Jewish Virtual Library

- Case Study: The Pogrom in Kielce, The London School of Economics and Political Science by Anita J. Prazmowska

- The Truth about Kielce by Iwo Cyprian Pogonowski (arguing that the Soviets were responsible for the pogrom)

- Postwar Pogrom, The New York Times, July 23, 2006