John Ford: Difference between revisions

→Talkies: additional information |

|||

| Line 63: | Line 63: | ||

===Talkies=== |

===Talkies=== |

||

Ford was one of the pioneer directors of sound films; he shot Fox's first song sung on screen, for his film ''[[Mother Machree]]'' (1928) of which only three of the original seven reels survive; this film is also notable as the first Ford film to feature the young [[John Wayne]] (as an uncredited extra) and he performed as an extra in FGord's next two movies. Ford also directed Fox's first all-talking dramatic feature ''Napoleon's Barber'' (1928), a 3-reeler which is also now lost. |

Ford was one of the pioneer directors of sound films; he shot Fox's first song sung on screen, for his film ''[[Mother Machree]]'' (1928) of which only three of the original seven reels survive; this film is also notable as the first Ford film to feature the young [[John Wayne]] (as an uncredited extra) and he performed as an extra in FGord's next two movies. Ford also directed Fox's first all-talking dramatic feature ''Napoleon's Barber'' (1928), a 3-reeler which is also now lost. |

||

| ⚫ | Ford made a wide range of films in this period, and he became well-known for his Western and 'frontier' pictures, but the genre rapidly lost its appeal for major studios in the late 1920s. Ford's last silent Western was ''[[3 Bad Men]]'' (1926), set during the Dakota land rush and filmed at [[Jackson Hole]], Wyoming and in the [[Mojave Desert]]. and it would be thirteen years before he made his next Western, ''Stagecoach'', in 1939. |

||

Just before the studio converted to talkies, Fox imported celebrated German director [[F.W. Murnau]] to make the landmark silent drama ''[[Sunrise (film)|Sunrise]]'' (1927), which is still widely regarded by critics as one of the best films ever made. ''Sunrise'' had a powerful effect on many American filmmakers including Ford<ref>Gallagher, 1986, pp.49-61</ref> and Murnau's influence can be seen in many of his films of the late 1920s and early 1930s -- Ford's penultimate silent feature ''[[Four Sons]]'' (1928), starred Victor McLaglen and was filmed on some of the lavish sets left over from Murnau's production. His last silent feature ''[[Hangman's House]]'' (1928) is notable as one of the first screen appearance by [[John Wayne]]. |

Just before the studio converted to talkies, Fox imported celebrated German director [[F.W. Murnau]] to make the landmark silent drama ''[[Sunrise (film)|Sunrise]]'' (1927), which is still widely regarded by critics as one of the best films ever made. ''Sunrise'' had a powerful effect on many American filmmakers including Ford<ref>Gallagher, 1986, pp.49-61</ref> and Murnau's influence can be seen in many of his films of the late 1920s and early 1930s -- Ford's penultimate silent feature ''[[Four Sons]]'' (1928), starred Victor McLaglen and was filmed on some of the lavish sets left over from Murnau's production. His last silent feature ''[[Hangman's House]]'' (1928) is notable as one of the first screen appearance by [[John Wayne]]. |

||

''Napoloeon's Barber'' was followed by ''[[Riley the Cop]]'' (1928) and ''[[Strong Boy]]'' (1929), starring [[Victor McLaglen]], both of which are now lost (although Tag Gallagher's book records that the only surviving copy of ''Strong Boy'', a 35mm nitrate print, was rumoured to be held in a private collection in Australia<ref>Gallagher, 1986, p.519</ref>). ''[[The Black Watch]]'' (1929), a colonial army adventure set in the [[Khyber Pass]] |

''Napoloeon's Barber'' was followed by ''[[Riley the Cop]]'' (1928) and ''[[Strong Boy]]'' (1929), starring [[Victor McLaglen]], both of which are now lost (although Tag Gallagher's book records that the only surviving copy of ''Strong Boy'', a 35mm nitrate print, was rumoured to be held in a private collection in Australia<ref>Gallagher, 1986, p.519</ref>). ''[[The Black Watch]]'' (1929), a colonial army adventure set in the [[Khyber Pass]] starring Victor McLaglen and [[Myrna Loy]] is Ford's first complete surviving talking picture; it was remade in 1954 by [[Henry King (director)|Henry King]] as ''[[King of the Khyber Rifles]]''. |

||

Ford's output was quite constant from 1928 to the start of World War II; he made five features in 1928 and then made either two or three films every year from 1929-1942 inclusive. 1929 produced ''[[Strong Boy]]'', ''[[The Black Watch]]'' and ''Salute''; ''[[Men Without Women]]'' ''[[Born Reckless]]'' and ''[[Up the River]]'' (the debut film for both Spencer Tracy and Humphrey Bogart) in 1930; ''[[Seas Beneath]]'' ''[[The Brat]]'' and ''[[Arrowsmith]]'' in 1931; the last-named, adapted from the [[Sinclair Lewis]] novel and starring Ronald Colman and Helen Hayes, marked Ford's first [[Academy Awards]] recognition, with five nominations including Best Picture. |

|||

| ⚫ | Ford's efficiency and his ability to craft films that combined artfulness with strong commercial appeal won Ford icreasing renown and by 1940 he was acknowledged as one of the world's top directors. His growing prestige was reflected in his remuneration -- in 1920, when he moved to Fox, he was being paid $300-600 per week but as his career took off in the mid-Twenties his annual income skyrocketed. He earned nearly $134,000 in 1929, and he made over US$100,000 per annum ''every year'' from 1934 to 1941, earning a staggering $220,068 in 1938<ref>Gallagher, 1986, p.498-99</ref> -- more than double the salary of the U.S. President at that time. |

||

With production slowed by the Depression, Ford made two films each in 1932 and 1933 -- ''[[Airmail]]'' (made for Universal) with a young Ralph Bellamy and ''[[Flesh]]'' (for MGM) with [[Wallace Beery]]. In 1933 returned to Fox for ''[[Pilgrimage]]'' and ''[[Doctor Bull]]'', the first of three films with ''[[Will Rogers]]'' |

|||

The desert drama ''[[The Lost Patrol]]'' (1934), starring [[Victor McLagen]] and [[Boris Karloff]], was rated by both the [[National Board of Review]] and ''[[The New York Times]]'' as one of the Top 10 films of that year and won an Oscar for its score by [[Max Steiner]]<ref>Gallagher, 1986, p.97</ref>. It was followed later that year by ''[[The World Moves On]]'' with [[Madeleine Carroll]] and [[Franchot Tone]], and the highly successful ''[[Judge Priest]]'', his second film with Will Rogers, which became one of the top-grossing movies of the year. |

|||

| ⚫ | Ford made a wide range of films in this period, and he became well-known for his Western and 'frontier' pictures, but the genre rapidly lost its appeal for major studios in the late 1920s. Ford's last silent Western was ''[[3 Bad Men]]'' (1926), set during the Dakota land rush and filmed at [[Jackson Hole]], Wyoming and in the [[Mojave Desert]]. |

||

Ford's first 1935 film (made for [[Columbia Pictures|Columbia]]) was the mistaken-identity comedy ''[[The Whole Town's Talking]]'' with [[Edward G. Robinson]] and [[Jean Arthur]], released in the UK as ''Passport to Fame'', and it |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

which drew critical praise at the time. ''[[Steamboat Round The Bend]]'' was his third film with Will Rogers and seems probable they would have continued working together, but their collaboration was cut short by Rogers' untimely death in a plane crash in May 1935, which devastated Ford. |

|||

Ford confirmed his position in the top rank of American directors with the Murnau-influenced [[IRA]] drama ''[[The Informer]]'' (1935), starring Victor McLaglen. It earned great critical praise, was nominated for Best Picture and won Ford his first [[Academy Award]] for Best Director, and was hailed at the time as one of the best films ever made, although its reputation has diminished considerably when compared to other contenders like ''[[Citizen Kane]]''<ref>[http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0000406/bio Jon C. Hopwood - IMDb mini-biography of John Ford</ref>. |

|||

The politically charged ''[[The Prisoner of Shark Island]]'' (1936) -- which marked the debut of long-serving "stock player" [[John Carradine]] -- explored the little-known story of [[Samuel Mudd]], a doctor who was caught up in the [[Abraham_Lincoln_assassination]] conspiracy and consigned to an offshore prison after he treated the injured [[John Wilkes Booth]]. Other notable films of this period include the Elizabethan costume drama ''[[Mary of Scotland]]'' (1936) which brought him together with [[Katherine Hepburn]], the South Seas melodrama ''[[The Hurricane]]'' (1937) and the light-hearted [[Shirley Temple]] vehicle ''[[Wee Willie Winkie]]'' (1937), each of which had a first-year US gross of more than $1 million. |

The politically charged ''[[The Prisoner of Shark Island]]'' (1936) -- which marked the debut of long-serving "stock player" [[John Carradine]] -- explored the little-known story of [[Samuel Mudd]], a doctor who was caught up in the [[Abraham_Lincoln_assassination]] conspiracy and consigned to an offshore prison after he treated the injured [[John Wilkes Booth]]. Other notable films of this period include the Elizabethan costume drama ''[[Mary of Scotland]]'' (1936) which brought him together with [[Katherine Hepburn]], the South Seas melodrama ''[[The Hurricane]]'' (1937) and the light-hearted [[Shirley Temple]] vehicle ''[[Wee Willie Winkie]]'' (1937), each of which had a first-year US gross of more than $1 million. |

||

Revision as of 11:48, 5 April 2009

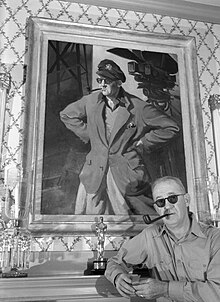

John Ford | |

|---|---|

| File:John Ford.jpg | |

| Born | John Martin Feeney |

| Spouse | Mary Ford (1920-1973) |

| Awards | AFI Life Achievement Award 1973 Lifetime Achievement |

John Ford (February 1 1894 – August 31 1973)[1] was an American film director of Irish heritage famous for both his westerns such as Stagecoach and The Searchers and adaptations of such 20th-century American novels as The Grapes of Wrath. His four Best Director Academy Awards (1935, 1940, 1941, 1952) is a record, although only one of those films, How Green Was My Valley, won Best Picture.

In a career that spanned more than 50 years, Ford directed 140 films (although nearly all of his silent films are now lost) and he is widely regarded as one of the most important American filmmakers of his generation[2]. Ford's films and personality have been highly influential, leading colleagues such as Ingmar Bergman and Orson Welles to name him as one of the greatest directors of all time.

In particular, Ford was a pioneer of location shooting and the long shot which frames his characters against a vast, harsh and rugged natural terrain. Ford has further influenced directors as diverse as Akira Kurosawa, Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, Sam Peckinpah, Peter Bogdanovich, Sergio Leone, Clint Eastwood, Wim Wenders, Pedro Costa, Judd Apatow, David Lean, Orson Welles, Ingmar Bergman, Quentin Tarantino, John Milius, François Truffaut, and Jean-Luc Godard.

From Feeney to Ford

He was born John Martin "Jack" Feeney (though he later often gave his given names as Sean Aloysius, sometimes with surname O'Feeny or O'Fearna; a Gaelic equivalent of Feeney) in Cape Elizabeth, Maine to John Augustine Feeney and Barbara "Abbey" Curran, on February 1, 1894 (though he occasionally said 1895 and that date is erroneously on his tombstone).[1] His father, John Augustine, was born in Spiddal,[3] County Galway, Ireland in 1854.[1] Barbara Curran had been born in the Aran Islands, in the town of Kilronan on the island of Inishmore (Inis Mór).[1]

John A. Feeney's grandmother, Barbara Morris, was said to be a member of a local (impoverished) gentry family, the Morrises of Spiddal, headed at present by Lord Killanin.

John Augustine and Barbara Curran arrived in Boston and Portland respectively within a few days of each other in May and June 1872. They were married in 1875, and became American citizens five years later on September 11, 1880.[1] They had eleven children: Mamie (Mary Agnes), born 1876; Delia (Edith), 1878-1881; Patrick; Francis Ford, 1881-1953; Bridget, 1883-1884; Barbara, born and died 1888; Edward, born 1889; Josephine, born 1891; Hannah (Joanna), born and died 1892; John Martin, 1894-1973; and Daniel, born and died 1896 (or 1898).[1] John Augustine lived in the Munjoy Hill neighborhood of Portland, Maine with his family, and would try farming, fishing, work for the gas company, run a saloon, and be an alderman.[1]

Feeney attended Portland High School, Portland, Maine. He moved to California and began acting and working in film production fort his older brother Francis in 1914, taking "Jack Ford" as a stage name. In addition to credited roles, he appeared uncredited as a Klansman in D.W. Griffith's 1915 classic, The Birth of a Nation, as the man who lifts up one side of his hood so he can see clearly.

He married Mary McBryde Smith, on July 3, 1920 and they had two children. Ford never divorced his wife, but he had many extramarital relationships[4] including an intense six-month affair with Katharine Hepburn, the star of Mary of Scotland (1936). The longer revised version of Directed by John Ford shown on Turner Classic Movies in November, 2006 features directors Steven Spielberg, Clint Eastwood, and Martin Scorsese, who suggest that the string of classic films Ford directed 1936-1941 was due in part to his affair with Hepburn.

Ford was sensitive, sentimental and erudite but, to protect himself in the cutthroat atmosphere of Hollywood, he cultivated the image of a "tough, two-fisted, hard-drinking Irish sonofabitch" (Harry "Dobe" Carey Jr). One famous event, witnessed by Ford's actor friend Frank Baker, strikingly illustrates the tension between the public persona and the private man. During the Depression, Ford -- by then a very wealthy man -- was accosted outside his office by a former Universal actor who was destitute and needed $200 for an operation for his wife. As the man related his misfortunes, Ford appeared to become enraged and then, to the horror of onlookers, he launched himself at the man, knocked him to the floor and shouted "How dare you come here like this? Who do think you are to talk to me this way?" before storming out of the room. However, as the shaken old man left the building, Frank Baker saw Ford's business manager Fred Totman meet him at the door, where he handed the man a cheque for $1000 and instructed Ford's chauffeur to drive him home. There, an ambulance was waiting to take the man's wife to the hospital where a specialist, flown in from San Francisco at Ford's expense, performed the operation. Some time later, Ford purchased a house for the couple and pensioned them for life. When Baker related the story to Francis Ford, he declared it the key to his brother's personality:

- "Any moment, if that old actor had kept talking, people would have realised what a softy Jack is. He couldn't have stood through that sad story without breaking down. He's built this whole legend of toughness around himself to protect his softness."[5]

Although Ford had many affairs with women, there were occasional rumours about his sexual preferences[6] and in her 2004 autobiography 'Tis Herself, Maureen O'Hara recalled seeing Ford kissing a famous male actor (whom she did not name) on the set of The Long Gray Line.

Director

John Ford began his career in film after moving to California in July 1914. He was following in the footsteps of his multi-talented older brother Francis Ford, twelve years his senior, who had left home years earlier and had worked in vaudeville before becoming a movie actor. Francis played in hundreds of silent pictures for Thomas Edison, Georges Melies and Thomas Ince, eventually progressing to become a top actor-writer-director with his own production company (101 Bison) at Universal[7].

Jack Ford started out as an assistant/handyman and occasional actor in his brother's films and Francis gave his younger brother his first acting role in The Mysterious Rose (Nov. 1914)[8]. Despite their combative relationship within three years Jack had progressed to become Francis' chief assistant and often cameraman[9], by which time Francis' profile was declining.

The Silent Era

During his first decade as a director Ford honed his craft on dozens of features (including many westerns) but sadly only a handful of the more than fifty silent films he made between 1917 and 1928 have survived in any form.[10].

Ford made his directorial debut with the silent two-reeler The Tornado (March 1917); according to Ford's own story, he was given the job by Universal boss Carl Laemmle who supposedly said, "Give Jack Ford the job -- he yells good". The Tornado was quickly followed by a string of two- and three-reelers -- The Trail of Hate, The Scrapper, The Soul Herder and Cheyenne's Pal, all made over the space of a few months and each typically shot in 2-3 days (and all now presumed lost). The Soul Herder is also notable as the beginning of Ford's four-year, 25-film association with veteran writer-actor Harry Carey[11], who (alongside Francis Ford) was a strong early influence on the young director. Carey's son Harry "Dobe" Carey Jr, who also became an actor, was one of Ford's closest friends in later years and featured in many of his most celebrated westerns.

Ford's first feature-length production was Straight Shooting (Aug. 1917), which is also his earliest surviving film as director and the only survivor of his twenty-five films with Harry Carey. On this film Ford and Carey disobeyed studio orders and turned in five reels instead of two, and it was only through the intervention of Carl Laemmle that the film escaped being cut for its first release, although it was subsequently edited down to two reels for re-release in the late 1920s[12].

Ford directed around thirty films over three years at Universal before moving to the Fox studio in 1920. His first film for Fox was Just Pals (1920). His 1923 feature Cameo Kirby, starring John Gilbert -- another of the few surviving Ford silents -- marked his first directing credit under the name "John Ford", rather than "Jack Ford", as he had previously been credited.

Ford's major breakthrough as a director was the historical drama The Iron Horse (1924), an epic account of the building of the First Transcontinental Railroad. It was a large, long and difficult production, filmed on location in the Sierra Nevada. The logistics were enormous -- two entire towns were constructed, there were 5000 extras, 100 cooks, 2000 rail layers, a cavalry regiment, 800 Indians, 1300 buffalo, 2000 horses, 10,000 cattle and 50,000 properties, including the original stagecoach used by Horace Greeley, Wild Bill Hickock's derringer pistol and replicas of the "Jupiter" and "119" locomotives that met at Promontory Point when the two ends of the line were joined on 10 May 1869.

Ford's brother Eddie was a crew member and they fought constantly; on one occasion Eddie reportedly "went after the old man with a pick handle". There was only a short synopsis written when filming began and Ford wrote the film day by day, then shot it. Production fell behind schedule, delayed by constant bad weather and the intense cold, and the studio grew desperate for footage. Fox executives repeatedly demanded results, but Ford would either tear up the telegrams or hold them up and have stunt gunman Edward "Pardner" Jones shoot holes through the sender's name. Despite the pressure to halt the production, studio boss William Fox finally backed Ford and allowed him to finish the picture and his gamble paid off handsomely -- The Iron Horse became one of the top-grossing films of the decade, taking over US$2 million worldwide, against a budget of $280,000.[13]

During the 1920s, Ford also served as president of the Motion Picture Directors Association, a forerunner to today's Directors Guild of America.

Talkies

Ford was one of the pioneer directors of sound films; he shot Fox's first song sung on screen, for his film Mother Machree (1928) of which only three of the original seven reels survive; this film is also notable as the first Ford film to feature the young John Wayne (as an uncredited extra) and he performed as an extra in FGord's next two movies. Ford also directed Fox's first all-talking dramatic feature Napoleon's Barber (1928), a 3-reeler which is also now lost.

Ford made a wide range of films in this period, and he became well-known for his Western and 'frontier' pictures, but the genre rapidly lost its appeal for major studios in the late 1920s. Ford's last silent Western was 3 Bad Men (1926), set during the Dakota land rush and filmed at Jackson Hole, Wyoming and in the Mojave Desert. and it would be thirteen years before he made his next Western, Stagecoach, in 1939.

Just before the studio converted to talkies, Fox imported celebrated German director F.W. Murnau to make the landmark silent drama Sunrise (1927), which is still widely regarded by critics as one of the best films ever made. Sunrise had a powerful effect on many American filmmakers including Ford[14] and Murnau's influence can be seen in many of his films of the late 1920s and early 1930s -- Ford's penultimate silent feature Four Sons (1928), starred Victor McLaglen and was filmed on some of the lavish sets left over from Murnau's production. His last silent feature Hangman's House (1928) is notable as one of the first screen appearance by John Wayne.

Napoloeon's Barber was followed by Riley the Cop (1928) and Strong Boy (1929), starring Victor McLaglen, both of which are now lost (although Tag Gallagher's book records that the only surviving copy of Strong Boy, a 35mm nitrate print, was rumoured to be held in a private collection in Australia[15]). The Black Watch (1929), a colonial army adventure set in the Khyber Pass starring Victor McLaglen and Myrna Loy is Ford's first complete surviving talking picture; it was remade in 1954 by Henry King as King of the Khyber Rifles.

Ford's output was quite constant from 1928 to the start of World War II; he made five features in 1928 and then made either two or three films every year from 1929-1942 inclusive. 1929 produced Strong Boy, The Black Watch and Salute; Men Without Women Born Reckless and Up the River (the debut film for both Spencer Tracy and Humphrey Bogart) in 1930; Seas Beneath The Brat and Arrowsmith in 1931; the last-named, adapted from the Sinclair Lewis novel and starring Ronald Colman and Helen Hayes, marked Ford's first Academy Awards recognition, with five nominations including Best Picture.

Ford's efficiency and his ability to craft films that combined artfulness with strong commercial appeal won Ford icreasing renown and by 1940 he was acknowledged as one of the world's top directors. His growing prestige was reflected in his remuneration -- in 1920, when he moved to Fox, he was being paid $300-600 per week but as his career took off in the mid-Twenties his annual income skyrocketed. He earned nearly $134,000 in 1929, and he made over US$100,000 per annum every year from 1934 to 1941, earning a staggering $220,068 in 1938[16] -- more than double the salary of the U.S. President at that time.

With production slowed by the Depression, Ford made two films each in 1932 and 1933 -- Airmail (made for Universal) with a young Ralph Bellamy and Flesh (for MGM) with Wallace Beery. In 1933 returned to Fox for Pilgrimage and Doctor Bull, the first of three films with Will Rogers

The desert drama The Lost Patrol (1934), starring Victor McLagen and Boris Karloff, was rated by both the National Board of Review and The New York Times as one of the Top 10 films of that year and won an Oscar for its score by Max Steiner[17]. It was followed later that year by The World Moves On with Madeleine Carroll and Franchot Tone, and the highly successful Judge Priest, his second film with Will Rogers, which became one of the top-grossing movies of the year.

Ford's first 1935 film (made for Columbia) was the mistaken-identity comedy The Whole Town's Talking with Edward G. Robinson and Jean Arthur, released in the UK as Passport to Fame, and it which drew critical praise at the time. Steamboat Round The Bend was his third film with Will Rogers and seems probable they would have continued working together, but their collaboration was cut short by Rogers' untimely death in a plane crash in May 1935, which devastated Ford.

Ford confirmed his position in the top rank of American directors with the Murnau-influenced IRA drama The Informer (1935), starring Victor McLaglen. It earned great critical praise, was nominated for Best Picture and won Ford his first Academy Award for Best Director, and was hailed at the time as one of the best films ever made, although its reputation has diminished considerably when compared to other contenders like Citizen Kane[18].

The politically charged The Prisoner of Shark Island (1936) -- which marked the debut of long-serving "stock player" John Carradine -- explored the little-known story of Samuel Mudd, a doctor who was caught up in the Abraham_Lincoln_assassination conspiracy and consigned to an offshore prison after he treated the injured John Wilkes Booth. Other notable films of this period include the Elizabethan costume drama Mary of Scotland (1936) which brought him together with Katherine Hepburn, the South Seas melodrama The Hurricane (1937) and the light-hearted Shirley Temple vehicle Wee Willie Winkie (1937), each of which had a first-year US gross of more than $1 million.

1939-1941

Stagecoach (1939) was Ford's first western in thirteen years and his first with sound. It is arguably the keystone work of the Ford oeuvre and remains one of the most admired, studied and imitated of all Hollywood movies, not least for its climactic chase scene and the hair-raising horse-jumping stunt, performed by the legendary Yakima Canutt. It also marked the beginning of the most successful phase of Ford's career -- in just two years between 1939 and 1941 he created a string of masterpieces including Stagecoach, Young Mr Lincoln, Drums Along the Mohawk, The Grapes of Wrath and How Green Was My Valley, which between them won numerous Academy Awards, including two Best Director Oscars and his only career award for Best Picture.

Although low-budget Western features and serials were still being churned out in large numbers by "Poverty Row" studios, they had fallen out of favour with the big studios and were regarded as B-grade 'pulp' movies at best. Ford shopped the project around Hollywood for almost a year, offering it unsuccessfully to both Joseph Kennedy and David O. Selznick before linking with Walter Wanger, an independent producer working through United Artists.

Stagecoach is significant for many reasons -- it exploded industry prejudices by becoming a major critical and commercial hit -- it took over US$1 million in its first year (against a budget of just under $400,000) -- and its success single-handedly revitalized the moribund genre, showing that Westerns could be "intelligent, artful, great entertainment -- and profitable"[19]. It was nominated for seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director, and won two Oscars, for Best Supporting Actor (Thomas Mitchell) and Best Score. Stagecoach was the first in the series of seven classic Ford Westerns filmed on location in Monument Valley and was followed by My Darling Clementine (1946), Fort Apache (1948), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), The Searchers (1956), Sergeant Rutledge (1960), and Cheyenne Autumn (1964).

Ford based the film on a story he had spotted in Collier's magazine; he purchased the screen rights for just $2500 and the scenario was developed by Dudley Nichols. Walter Wanger urged Ford to hire Gary Cooper and Marlene Dietrich for the lead roles, but eventually accepted Ford's decision to cast Claire Trevor as Dallas and a virtual unknown -- his old friend John Wayne -- as Ringo, and Wanger had little further influence over the production[20]. Wayne had good reason to be grateful for Ford's choice and Stagecoach provided the actor with the career breakthrough that elevated him to international stardom. Over 35 years Wayne appeared in twenty-four of Ford's films (and three TV episodes), including Stagecoach (1939), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), The Quiet Man (1952), The Searchers (1956), The Wings of Eagles (1957), and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962). Ford is credited with playing a major role in shaping Wayne's screen image.

Young Mr Lincoln (1939), starring Henry Fonda was less successful, attracting little critical attention and winning no awards. It was not a major financial success, although it had a respectable domestic first year gross of $750,000 but Ford scholar Tag Gallagher describes it as "a deeper, more multileveled work than Stagecoach .... (which) seems in retrospect one of the finest prewar pictures"[21]

Drums Along the Mohawk (1939) included uncredited script contributions by William Faulkner. Ford's first movie in colour was a lavish frontier drama again starring Fonda, with Claudette Colbert. It was another big box-office success, grossing $1.25 million in its first year in the US and winning Edna May Oliver a Best Supporting Actress Oscar for her performance.

Despite its strident political stance, Ford's screen adaptation of John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath (photographed byGregg Toland) was both a box office hit and a critical success, and it is still widely regarded as one of the best films of Ford's career. Noted critic Andrew Sarris has described it as the movie that transformed Ford from "a storyteller of the screen into America's cinematic poet laureate"[22]. His third movie in a year and his third consecutive film with Fonda, it grossed $1.1 million in the USA in its first year[23] and won two Academy Awards -- Ford's second 'Best Director' Oscar, and 'Best Supporting Actress' for Jane Darwell's tour-de-force portrayal of Ma Joad.

The Grapes of Wrath was followed by two less successful and lesser known films. The Long Voyage Home (1940) was, like Stagecoach, made with Walter Wanger through United Artists. Adapted from four plays by Eugene O'Neill plays, it was scripted by Dudley Nichols with Ford, in consultation with O'Neill himself. Although not a significant box-office success (it grossed only $600,000 in its first year) it was nominated for seven Academy Awards -- Best Picture, Best Screenplay, (Nichols), Best Music (Best Photography (Gregg Toland), Best Editing (Sherman Todd), Best Effects (Ray Binger & R.T. Layton), and Best Sound (Robert Parrish). It was one of Ford's personal favourites -- stills from it decorated his home --- and O'Neill also loved the film and screened it periodically[24].

Tobacco Road (1941) was a hillbilly comedy scripted by Nunnally Johnson, adapted from the long-running Jack Kirkland stage version of the novel by Erskine Caldwell. It starred veteran actor Charley Grapewin and the supporting cast included Ford regulars Ward Bond and Mae Marsh, with Francis Ford in an uncredited bit part, and it is also notable for early screen appearances by future stars Gene Tierney and Dana Andrews. Although not highly regarded by some critics (Tag Gallagher devotes only one short paragraph to it in his book on Ford[25]) it was quite successful at the box office, grossing $900,000 in its first year. According to IMDb, the film was banned in Australia for unspecified reasons[26].

Ford's last feature before America joined the war was the classic screen adaptation of How Green Was My Valley (1941), starring Walter Pidgeon, Maureen O'Hara and Roddy McDowell in his career-making role as Huw. The script was written by Philip Dunne from the best-selling novel by Robert Llewellyn and the screen rights alone cost Fox $300,000. It was originally planned as a four-hour epic to rival Gone With The Wind, and was to have been filmed on location in Wales, but this was abandoned due the heavy German bombing of Britain and the nervousness of Fox executives about the pro-union tone of the story[27]. Director William Wyler was replaced by Ford, and Fox's San Fernando Valley ranch substituted for Wales. Producer Darryl F. Zanuck had a strong influence over the movie and he made several key decisions including the idea of having the character of Huw narrate the film in voice-over (a novel concept in 1940), and the decision that Huw's character should not age (Tyrone Power was originally slated to play the adult Huw)[28].

How Green Was My Valley became one of the biggest films of 1940. It was nominated for ten Academy Awards including Best Supporting Actress (Sara Allgood), Best Editing, Best Script, Best Music and Best Sound and it won five Oscars -- Best Director, Best Picture, Best Supporting Actor (Donald Crisp), Best B&W Cinematography (Arthur C. Miller) and Best Art Direction/Interior Decoration. It was a huge hit with audiences, coming in behind Sergeant York as the second-highest grossing film of the year in the USA and taking almost $3 million against its sizable budget of $1,250,000[29]. Ford was also named Best Director by the New York Film Critics, and this was one of the few awards of his career that he turned up to collect in person (he generally shunned the Oscar ceremony)[30].

The War Years

During World War II Commander John Ford, USNR, served in the United States Navy and made documentaries for the Navy Department. He won two more Academy Awards during this time, one for the semi-documentary The Battle of Midway (1942), and a second for the propaganda film December 7th (1943).[31][32][33]

Ford was present on Omaha Beach on D-Day. As head of the photographic unit for the Office of Strategic Services, he crossed the English Channel on the USS Plunkett (DD-431), anchored off Omaha Beach at 0600. He observed the first wave land on the beach from the ship, landing on the beach himself later with a team of US Coast Guard cameramen who filmed the battle from behind the beach obstacles, with Ford directing operations. The film was edited in London, but very little was released to the public. Ford explained in a 1964 interview that the US Government was "afraid to show so many American casualties on the screen", adding that all of the D-Day film "still exists in color in storage in Anacostia near Washington, D.C."[34]. Thirty years later, historian Stephen E. Ambrose reported that the Eisenhower Center had been unable to find the film.[35] Ford eventually rose to become a top adviser to OSS head William Joseph Donovan. According to records released in 2008, Ford was cited by his superiors for bravery, taking a position to film one mission that was "an obvious and clear target." He survived "continuous attack and was wounded" while he continued filming, one commendation in his file states.[36]

Post-war career

After the war, Ford became a Rear Admiral in the United States Navy Reserve. His last wartime film was They Were Expendable (MGM, 1945), an account of America's disastrous defeat in The Philippines, told from the viewpoint of a torpedo squadron and its commander. Ford repeatedly declared that he disliked the film and had never watched it, complaining that he had been forced to make it, although it was later strongly championed by filmmaker Lindsay Anderson. Released several months after the end of the war, it was among the year's top box-office draws, although Tag Gallagher notes that many critics have incorrectly claimed that it lost money[37].

Ford directed sixteen features and several documentaries in the decade between 1945 and 1956. His output in this period includes some of his most highly regarded films, notably his "Cavalry Trilogy" (Fort Apache, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon and Rio Grande), The Quiet Man and The Searchers. As with his prewar films, Ford alternated between (relative) box office flops and major successes, although most of his later films made a solid profit, with Fort Apache, The Quiet Man, Mogambo and The Searchers all ranking in the Top 20 box-office hits of their respective years[38].

Ford's first postwar project My Darling Clementine (Fox, 1946), which reunited him with Henry Fonda, was a retelling of the primal Western legend of Wyatt Earp (Fonda), Doc Holliday (Victor Mature) and the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral. In contrast to his string of successes in 1939-41, it won no major American awards, although it was awarded a silver ribbon for Best Foreign Film in 1948 by the Italian National Syndicate of Film Journalists[39], and it was a solid financial success, grossing $2.75 million in the USA and $1.75 internationally in its first year of release[40].

The Fugitive (1946), again starring Fonda, was the first project by Ford's new independent production company Argosy Films, which he had formed with noted producer Merian C. Cooper. It was a loose adaptation of Grahame Greene's The Power and the Glory which Ford had originally intended to make at Fox before the war, with Thomas Mitchell as the priest. It fared poorly compared to its predecessor, grossing only $750,000 in its first year, and did not make a profit. It also caused a rift between Ford and scriptwriter Dudley Nichols and brought about the end of their highly successful collaboration.

Fort Apache (Argosy/RKO, 1948), the first part of Ford's famed "Cavalry Trilogy", featured many of the "Stock Company" actors who had worked with Ford in the past, including John Wayne, Henry Fonda, Ward Bond, Shirley Temple, Victor McLaglen, Mae Marsh, Francis Ford (as a bartender), Frank Baker and Ben Johnson. It also marked the start of the long association between Ford and scriptwriter Frank S. Nugent, a former New York Times film critic who (like Dudley Nichols) had not written a movie script until hired by Ford[41]. It was a big commercial success, grossing $3 million in the USA and nearly $2 million internationally in its first year and ranking among the Top 20 box office hits of 1948[42]. During the year Ford also assisted his friend and colleague Howard Hawks, who was having problems with his current film Red River (which also starred John Wayne) and Ford reportedly made numerous editing suggestions, including the use of a narrator[43].

In 1955, Ford was tapped to direct the classic Navy comedy Mister Roberts, starring Henry Fonda, Jack Lemmon, William Powell, and James Cagney. However, Mervyn LeRoy replaced Ford during filming when he suffered a ruptured gallbladder.

Despite the success of his many previous films in this genre, Ford made only one Western in the period between 1950 and 1959. The Searchers (1956) gave John Wayne one of the best roles of his career and is also notable for an early screen appearance by future superstar Natalie Wood. Filmed in Ford's beloved Monument Valley, it is widely regarded as one of Ford's best works and is considered one of the best Westerns ever made.

Ford cast Ward Bond as John Dodge, a character based on Ford himself, in the 1957 movie The Wings of Eagles, again starring his good friends John Wayne and Maureen O'Hara.

Personal and directing style

Personal style

John Ford was noted for his intense personality and his many idiosyncrasies, such as his inveterate pipe-smoking and his habit of chewing on a linen handkerchief while he was shooting -- each morning his wife would give him a dozen fresh handkerchiefs, but by the end of a day's filming the corners of all of them would be chewed to shreds. He always had music playing on the set and would routinely break for tea (Earl Grey) at mid-afternoon every day during filming. He rarely drank during the making of a film, but when a production wrapped he would typically lock himself in his study, wrapped only in a sheet, and go on a solitary drinking binge for several days, followed by routine contrition and a vow never to drink again.

He was famously messy and untidy; his study was always littered with books, papers and dirty clothes. He bought a brand new Rolls Royce in the 1930s, but never rode in it because his wife Mary would not let him smoke in it. His own car, a battered Ford roadster, was so dilapidated and untidy that he was once late for a studio meeting because the gate guard did not believe that he was John Ford the famous director and refused to let him in. He was also notorious for his dislike of studio executives -- he is said to have ordered a guard to keep Fox supremo Daryl F. Zanuck off the set, and on another occasion he brought an associate producer in front of the crew, stood him in profile and announced, "This is an associate producer -- take a good look because you won't be seeing him on this picture again".

Ford's pride and joy was his yacht,Araner, which he bought in 1934 and on which he lavished tens of thousands of dollars in repairs and improvements.

Directing style

Ford had many distinctive 'trademarks' as a director. In contrast to his contemporary Alfred Hitchcock, he never used storyboards -- he composed his pictures entirely in his head, without any written outline of the shots he would use[44]. Script development could be intense but, once approved, his screenplays were rarely rewritten. He hated long expository scenes and was famous for tearing pages out of a script to cut dialogue. During the making of one film, he was challenged by a studio executive about falling behind schedule, to which Ford responded by tearing an entire scene out of the script, declaring "There, now we're all caught up!", and indeed he never filmed the scene.

He rarely used camera movements or close-ups, preferring static medium or long shots, with his actors framed against dramatic vistas or expressionistically lit interiors. Many of his sound films include renditions of his favourite hymn, "Shall We Gather at the River?". If a doomed character was shown playing poker (e.g. gunman Tom Tyler in Stagecoach), the last hand he played would be the "death hand" -- two eights and two aces, one of them the ace of spades -- so-called because Wild Bill Hickock is said to have held this hand when he was murdered.

He was legendary for his discipline and efficiency on-set[45], and was notorious for being extremely tough on his actors, frequently mocking, yelling and bullying them; he was equally notorious for his sometimes sadistic practical jokes. Any actor foolish to demand star treatment could expect to receive the full force of Ford's relentless scorn. He once referred to John Wayne as a "big idiot" and even punched an unsuspecting Henry Fonda; Henry Brandon (probably best known as Chief Scar from The Searchers) once referred to Ford as: "The only man who could make John Wayne cry." [citation needed]. He likewise belittled Victor McLaglen, on one occasion reportedly bellowing through the megaphone: "D'ya known, McLaglen, that Fox are paying you $1200 a week to do things that I could get any child off the street to do better?"[46]

Despite his often difficult and demanding personality, many actors who worked with Ford acknowledged that he brought out the best in them. John Wayne remarked that "Nobody could handle actors and crew like Jack."[47] and Dobe Carey stated that "He had a quality that made everyone almost kill themselves to please him. Upon arriving on the set, you would feel right away that something special was going to happen. You would feel spiritually awakened all of a sudden."[48] Carey credits Ford with the inspiration of Carey's final film, Comanche Stallion (2005).

Ford's favorite location for his films was in southern Utah's Monument Valley. He defined images of the American West with some of the most beautiful and powerful cinematography ever shot, in such films as Stagecoach, The Searchers, Fort Apache, and She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, while the influence on the films of classic Western artists such as Frederic Remington and others has been examined.[49] Ford's evocative use of the territory for his Westerns has defined the images of the American West so powerfully that Orson Welles once said that other film-makers refused to shoot in the region out of fears of plagiarism.[50]

Ford typically shot only the footage he needed and he often filmed in sequence, minimizing the job of his film editors[51]. In making The Grapes of Wrath (which runs 108 mins) Ford reportedly exposed just 40,000 feet of film, which equates to the remarkably low shooting ratio of 4:1[52]. The shooting ratio for feature films typically ranges from 6:1 to 10:1 or more and, by comparison, it is reported that Kevin Costner shot almost 1 million feet of film in the making of Dances With Wolves (which runs 180 mins)[53]

In the opinion of Joseph McBride [54], Ford's technique of cutting in the camera enabled him to retain creative control in a period where directors often had little say on the final editing of their films. Ford noted:

- "I don’t give ‘em a lot of film to play with. In fact, Eastman used to complain that I exposed so little film. I do cut in the camera. Otherwise, if you give them a lot of film ‘the committee’ takes over. They start juggling scenes around and taking out this and putting in that. They can’t do it with my pictures. I cut in the camera and that's it. There's not a lot of film left on the floor when I’m finished."[55]

His good friend Merian C. Cooper, the co-director of King Kong (1933), produced several of Ford's most admired films.

Ford used many of the same actors repeatedly in his films, far more so than many directors. Will Rogers, Harry Carey Sr, John Wayne, Henry Fonda, Ben Johnson, Chill Wills, Ward Bond, Grant Withers, Harry Carey, Jr., Ken Curtis, Victor McLaglen, Dolores del Rio, Pedro Armendariz, Woody Strode, Francis Ford (Ford's older brother), Hank Worden, John Qualen, Barry Fitzgerald, Arthur Shields, John Carradine, and Carleton Young were among this group, informally known as the John Ford Stock Company.

Ford died in Palm Desert, California, aged 79 from stomach cancer. He was interred in the Holy Cross Cemetery in Culver City, California. A statue of Ford in Portland, Maine depicts him sitting in a director's chair.

Awards

Ford won four Academy Awards as Best Director for The Informer (1935), The Grapes of Wrath (1940), How Green Was My Valley (1941), and The Quiet Man (1952) - none of them Westerns (also starring in the last two was Maureen O'Hara, "his favorite actress"). He was also nominated as Best Director for Stagecoach (1939). Ford is the only director to have won four Best Director Academy Awards: both William Wyler and Frank Capra won the award three times.

As a producer he received nominations for Best Picture for The Quiet Man and The Long Voyage Home.

He was the first recipient of the American Film Institute Life Achievement Award in 1973. Also in that year, Ford was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Richard Nixon.

In 2007, Twentieth Century Fox released "Ford at Fox", a DVD boxed set of 24 of Ford's films. Time magazine's Richard Corliss named it one of the "Top 10 DVDs of 2007", ranking it at #1. [56]

Academy Awards

The Battle of Midway Academy Award for Documentary Feature

December 7th (film) Academy Award for Documentary Short Subject

Politics

Ford's politics were conventionally progressive as his favorite presidents were Democrats Franklin D. Roosevelt and John F. Kennedy and Republican Abraham Lincoln[57] But despite these leanings, many thought[58][59] he was a Republican because of his long association with actors John Wayne, James Stewart, Maureen O'Hara and Ward Bond. Time magazine editor Whittaker Chambers wrote a harsh review of The Grapes of Wrath as left-wing propaganda, assuming Steinbeck, the author, and Ford to be of that political stripe.

Ford's attitude to McCarthyism in Hollywood is expressed by a story told by Joseph L. Mankiewicz. A faction of the Directors Guild of America led by Cecil B. DeMille had tried to make it mandatory for every member to sign a loyalty oath. A whispering campaign was being conducted against Mankiewicz, then President of the Guild, alleging he had communist sympathies. At a crucial meeting of the Guild, DeMille's faction spoke for four hours until Ford spoke against DeMille and proposed a vote of confidence in Mankiewicz, which was passed. His words were recorded by a court stenographer:

- "My name's John Ford. I make Westerns. I don't think there's anyone in this room who knows more about what the American public wants than Cecil B. DeMille — and he certainly knows how to give it to them.... [looking at DeMille] But I don't like you, C.B. I don't like what you stand for and I don't like what you've been saying here tonight."[60]

However, as time went on, Ford became more publicly allied with the Republican Party, declaring himself a 'Maine Republican' in 1947. He voted for Barry Goldwater in 1964, Richard Nixon in 1968 and became a supporter of the Vietnam War. In 1973, he was awarded the Medal of Freedom by President Nixon, whose campaign he had publicly supported.[61]

Filmography

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h Eyman, Scott. years active:1917-66Print the Legend: The Life and Times of John Ford. New York: Simon & Schuster. 1999. ISBN 0684811618 (excerpt c/o New York Times)

- ^ Gallagher, Tag John Ford: The Man and his Films (University of California Press, 1984), 'Preface'

- ^ Probably better known at the time by its Gaelic name An Spidéal.

- ^ Gallagher, Tag John Ford: The Man and his Films (University of California Press 1984) p.380

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, pp.40-41

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, p.381

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, p.6

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, p.13

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, p.15

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, pp.502-546

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, p.17

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, p.19

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, p.31

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, pp.49-61

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, p.519

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, p.498-99

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, p.97

- ^ [http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0000406/bio Jon C. Hopwood - IMDb mini-biography of John Ford

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, p.145

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, p.146

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, p.162

- ^ Quoted in Joseph McBride, "The Searchers", Sight & Sound, Spring 1972, p. 212

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, p. 499

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, p. 182

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, p.183

- ^ IMDb - Tobacco Road - Trivia

- ^ IMDb - "How Green Was My Valley - Trivia

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, pp.184-185

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, p.499

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, p.184

- ^ John Ford - at IMDb

- ^ Biography of Rear Admiral John Ford; U.S. Naval Reserve - at Naval Historical Center

- ^ "Oral History - Battle of Midway:Recollections of Commander John Ford" - at Naval Historical Center

- ^ Martin, Pete, "We Shot D-Day on Omaha Beach (An Interview With John Ford)", The American Legion Magazine, June 1964 from thefilmjournal.com, retrieved 14 February 2007

- ^ Ambrose, Stephen E. D-Day, June 6, 1944: The Climactic Battle of World War II. New York: Simon & Schuster. 1994. pp 395-397. ISBN 0-671-67334-3

- ^ "Spy Tales: a TV Chef, Oscar Winner, JFK Adviser," BRETT J. BLACKLEDGE and RANDY HERSCHAFT, The Associated Press

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, p. 225

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, pp.499-500

- ^ IMDb - My Darling Celementine - Awards

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, p.499

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, p. 247

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, p.499

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, p.531

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, p.464

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, op.cit., p.38

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, p.38

- ^ Eyman, Scott, Print The Legend: The Life and Times of John Ford, see below

- ^ Carey, Harry Jr. Company of Heroes: My Life as an Actor in the John Ford Stock Company

- ^ Peter Cowie, see below

- ^ Welles' narration for the film Directed by John Ford

- ^ BBC Radio 4 programme 10:30am 29 September 2007

- ^ Franklin, Richard John Ford (essay)

- ^ IMDb - Dances With Wolves, trivia

- ^ McBride, Joseph, Searching For John Ford: A Life, see below

- ^ Gallagher, Tag, John Ford: The Man and His Films, see below

- ^ Corliss, Richard, "Top 10 DVDs", Time magazine, retrieved from time.com, 14 February 2008

- ^ Peter Bogdanovich, John Ford, See below, pp 18-19.

- ^ Interview with Sam Pollard about Ford and Wayne from pbs.org

- ^ Roger Ebert, "The Grapes of Wrath", 30 March 2002, from rogerebert.com

- ^ Parrish, Robert (1996). "John Ford to the Rescue". Growing up in Hollywood. in Silvester, Christopher (2002), The Grove Book of Hollywood, Grove Press. p. 418. ISBN 0802138780. Retrieved 2008-08-15.

{{cite book}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ McBride, Joseph "The Convoluted Politics of John Ford" Los Angeles Times 3 June 2001[1]

References

- Bogdanovich, Peter. John Ford. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. 1967. Revised 1978. ISBN 0520034988

- Cowie, Peter. John Ford and the American West. New York: Harry Abrams Inc. 2004. ISBN 0810949768

- Eyman, Scott. Print the Legend: The Life and Times of John Ford. New York: Simon & Schuster. 1999. ISBN 0684811618

- Ford, Dan. The Unquiet Man: The Life of John Ford. London: Kimber. 1982 (1979). OCLC 9501332

- Gallagher, Tag. John Ford: The Man and His Films. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. 1986. ISBN 0520050975

- Mitry, Jean. John Ford. 1954.

- McBride, Joseph. Searching for John Ford: A Life. New York: St. Martin's Press. 2001. ISBN 0312242328

- Rollet, Patrice and Saad , Nicolas. John Ford. Paris: Editions de l'Etoile/Cahiers du cinéma : Diffusion, Seuil. 1990. ISBN 2866420934

- Sinclair, Andrew. John Ford. New York: Dial Press/J. Wade. 1979. ISBN 0803748264

External links

- John Ford at IMDb

- John Ford at Find a Grave

- Ford biography - at Yahoo! Movies

- "Ford Till '47" - by Tag Gallagher - at SensesofCinema.com

- "John Ford" - by Richard Franklin - at SensesofCinema.com

- Ford biography (with film poster illustration) - at ReelClassics.com

- Biography of Rear Admiral John Ford; U.S. Naval Reserve - at Naval Historical Center

- "Oral History - Battle of Midway:Recollections of Commander John Ford" - at Naval Historical Center

- John Ford Bibliography - at Film.Virtual-History.com

- "John Ford" - at TheyShootPictures.com

- John Ford document collection - at the Edmonton Public Library

- Talk on Ford in Portland, Maine, by Michael C. Connolly and Kevin Stoehr, editors of John Ford in Focus

Template:Persondata

{{subst:#if:Ford, John|}}

[[Category:{{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:1894}}

|| UNKNOWN | MISSING = Year of birth missing {{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:1973}}||LIVING=(living people)}}

| #default = 1894 births

}}]] {{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:1973}}

|| LIVING = | MISSING = | UNKNOWN = | #default =

}}

- Living people

- 1973 deaths

- American film directors

- American military personnel of World War II

- American Roman Catholics

- Best Director Academy Award winners

- Burials at Holy Cross Cemetery

- Irish-Americans

- Operation Overlord people

- People from Cumberland County, Maine

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Recipients of the Legion of Merit

- Recipients of the Purple Heart medal

- Deaths from stomach cancer

- United States Navy admirals

- Western (genre) film directors

- Cancer deaths in California