John Ford: Difference between revisions

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

Ford's first feature-length production -- and his earliest surviving film as director -- was ''Straight Shooting'' (Aug. 1917). On this film Ford and Carey disobeyed orders and turned in five reels instead of two, and it was only through the intervention of studio head [[Carl Laemmle]] that the film escaped being cut for its first release, although it was subsequently cut down to two reels for re-release in the late 1920s<ref>Gallagher, 1986, p.19</ref>. |

Ford's first feature-length production -- and his earliest surviving film as director -- was ''Straight Shooting'' (Aug. 1917). On this film Ford and Carey disobeyed orders and turned in five reels instead of two, and it was only through the intervention of studio head [[Carl Laemmle]] that the film escaped being cut for its first release, although it was subsequently cut down to two reels for re-release in the late 1920s<ref>Gallagher, 1986, p.19</ref>. |

||

Ford honed his craft on dozens of films over the next decade, including many westerns, but regrettably only a handful of the more than fifty silent features he made for Universal and Fox have survived in any form.<ref>Gallagher, 1986, pp.502-546</ref>. He directed around thirty films in three years at Universal (almost all now lost), before moving to the [[20th Century Fox| |

Ford honed his craft on dozens of films over the next decade, including many westerns, but regrettably only a handful of the more than fifty silent features he made for Universal and Fox have survived in any form.<ref>Gallagher, 1986, pp.502-546</ref>. He directed around thirty films in three years at Universal (almost all now lost), before moving to the [[20th Century Fox|Fox]] studio in 1920 and it was during his time at Fox that Ford advanced into the front rank of Hollywood directors. His first film for Fox was ''[[Just Pals]]'' (1920). His 1923 feature ''Cameo Kirby'', starring [[John Gilbert]] -- another of the few surviving Ford silents -- marked his first directing credit under the name "John Ford", rather than "Jack Ford", as he had previously been credited. |

||

| ⚫ | With the advent of sound in 1927-28, Ford abandoned the western genre for a decade and became one of the pioneers of the the sound format, directing Fox's first dramatic "talkie" ''Napoleon's Barber'' (now lost) and shooting Fox's first song sung on screen, for the film ''Mother Macree'' (of which only three of the original seven reels survive). Ford made a wide variety of films in the 1930s including the [[Expressionist]] [[IRA]] drama ''[[The Informer]]'' (1935) -- which earned him his first Oscar for Best Director -- the politically charged ''[[The Prisoner of Shark Island]]'' (1936, Ford's first film with [[John Carradine]]), the South Seas melodrama ''[[The Hurricane]]'' (1937), the Elizabethan costume drama ''[[Mary of Scotland]]'' (1936) starring [[Katherine Hepburn]], and the light-hearted [[Shirley Temple]] vehicle ''[[Wee Willie Winkie]]'' (1937). During the 1920s, he also served as president of the [[Motion Picture Directors Association]], a forerunner to today's [[Directors Guild of America]]. |

||

His first film for Fox was ''[[Just Pals]]'' (1920). His 1923 Fox feature ''Cameo Kirby'', starring [[John Gilbert]] -- another of the few surviving Ford silents -- marked his first screen credit as "John Ford", rather than "Jack Ford", as he had previously been known. It was during his time with Fox that Ford advanced into the front rank of Hollywood directors alongside |

|||

Ford's classic ''[[Stagecoach (film)|Stagecoach]]'' (1939) was his first western in ten years and his first with sound. This pivotal work ushered in the most successful period of his career and over the next two years he created a string of masterpieces including ''[[Young Mr Lincoln]]'', ''[[Drums Along The Mohawk]]'', ''[[The Grapes of Wrath]]'' and ''[[How Green Was My Valley]]''. ''Stagecoach'' single-handedly revived the moribund Western genre and it was a major critical and commercial success -- it was nominated for seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director, and won two Oscars for Best Supporting Actor (Thomas Mitchell) and Best Score. It was also the first in the series of seven classic Ford Westerns filmed on location in [[Monument Valley]] -- ''Stagecoach'', ''[[My Darling Clementine]]'' (1946), ''[[Fort Apache]]'' (1948), ''[[She Wore a Yellow Ribbon]]'' (1949), ''[[The Searchers]]'' (1956), ''[[Sergeant Rutledge]]'' (1960), and ''[[Cheyenne Autumn]]'' (1964). |

|||

| ⚫ | With the advent of sound in 1927-28, Ford became one of the pioneers of the |

||

| ⚫ | ''Stagecoach'' also provided the major career breakthrough Ford's friend [[John Wayne]] and Ford is credited with playing a major role in moulding Wayne's image. Over 35 years Wayne appeared in twenty-four of Ford's films (and three TV episodes), including ''[[Stagecoach (film)|Stagecoach]]'' (1939), ''[[She Wore a Yellow Ribbon]]'' (1949), ''[[The Quiet Man]]'' (1952), ''[[The Searchers (film)|The Searchers]]'' (1956), ''[[The Wings of Eagles]]'' (1957), and ''[[The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance]]'' (1962). |

||

Ford effectively abandoned the western genre for a decade and made a wide variety of films in the Thirties, including the moody [[Expressionist]] IRA drama ''[[The Informer]]'' (1935) and the historical drama ''[[Mary of Scotland]]'' (1936) starring [[Katherine Hepburn]] to the light-hearted [[Shirley Temple]] vehicle ''[[Wee Willie Winkie]]'' (1937) but he made a spectacular return to Westerns in 1939 with ''[[Stagecoach]]'', which won two Academy Awards. It was the career breakthrough for his friend [[John Wayne]] and is now acknowledged both as one of Ford's finest films and one of the classics of the genre. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Ford's favorite location for his films was in southern [[Utah]]'s [[Monument Valley]]. Ford defined images of the American West with some of the most beautiful and powerful cinematography ever shot, in such films as ''Stagecoach'', ''[[The Searchers (film)|The Searchers]]'', ''[[Fort Apache (film)|Fort Apache]]'', and ''[[She Wore a Yellow Ribbon]]'', while the influence on the films of classic Western artists such as [[Frederic Remington]] and others has been examined.<ref>Peter Cowie, see below</ref> Ford's evocative use of the territory for his Westerns has defined the images of the American West so powerfully that [[Orson Welles]] once said that other film-makers refused to shoot in the region out of fears of plagiarism.<ref> Welles' narration for the film ''Directed by John Ford''</ref> |

Ford's favorite location for his films was in southern [[Utah]]'s [[Monument Valley]]. Ford defined images of the American West with some of the most beautiful and powerful cinematography ever shot, in such films as ''Stagecoach'', ''[[The Searchers (film)|The Searchers]]'', ''[[Fort Apache (film)|Fort Apache]]'', and ''[[She Wore a Yellow Ribbon]]'', while the influence on the films of classic Western artists such as [[Frederic Remington]] and others has been examined.<ref>Peter Cowie, see below</ref> Ford's evocative use of the territory for his Westerns has defined the images of the American West so powerfully that [[Orson Welles]] once said that other film-makers refused to shoot in the region out of fears of plagiarism.<ref> Welles' narration for the film ''Directed by John Ford''</ref> |

||

Ford typically exposed only the footage he needed and he often shot in sequence, minimizing the job of his film editors.<ref>[[BBC Radio 4]] programme 10:30am [[29 September]] [[2007]]</ref> In the opinion of Joseph McBride <ref>McBride, Joseph, ''Searching For John Ford: A Life'', see below</ref>, his technique of cutting in the camera also enabled him to retain creative control in a period where directors had little say on the editing of their films, because, as Ford noted: |

|||

:"I don’t give ‘em a lot of film to play with. In fact, Eastman used to complain that I exposed so little film. I do cut in the camera. Otherwise, if you give them a lot of film ‘the committee’ takes over. They start juggling scenes around and taking out this and putting in that. They can’t do it with my pictures. I cut in the camera and that's it. There's not a lot of film left on the floor when I’m finished."<ref>Gallagher, Tag, ''John Ford: The Man and His Films'', see below</ref> |

:"I don’t give ‘em a lot of film to play with. In fact, Eastman used to complain that I exposed so little film. I do cut in the camera. Otherwise, if you give them a lot of film ‘the committee’ takes over. They start juggling scenes around and taking out this and putting in that. They can’t do it with my pictures. I cut in the camera and that's it. There's not a lot of film left on the floor when I’m finished."<ref>Gallagher, Tag, ''John Ford: The Man and His Films'', see below</ref> |

||

Revision as of 12:13, 19 March 2009

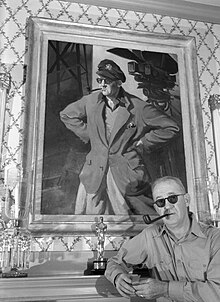

John Ford | |

|---|---|

| File:John Ford.jpg | |

| Born | John Martin Feeney |

| Spouse | Mary Ford (1920-1973) |

| Awards | AFI Life Achievement Award 1973 Lifetime Achievement |

John Ford (February 1 1894 – August 31 1973)[1] was an American film director of Irish heritage famous for both his westerns such as Stagecoach and The Searchers and adaptations of such 20th-century American novels as The Grapes of Wrath. His four Best Director Academy Awards (1935, 1940, 1941, 1952) is a record, although only one of those films, How Green Was My Valley, won Best Picture.

In a career that spanned more than 50 years, Ford directed 140 films (although nearly all of his early silent features are now lost) and he came to be regarded as one of the finest American filmmakers of his generation[2]. Ford's films and personality have been highly influential, leading colleagues such as Ingmar Bergman and Orson Welles to name him as one of the greatest directors of all time. In particular, Ford was a pioneer of location shooting and the long shot which frames his characters against a vast, harsh and rugged natural terrain. Ford has further influenced directors as diverse as Akira Kurosawa, Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, Sam Peckinpah, Peter Bogdanovich, Sergio Leone, Clint Eastwood, Wim Wenders, Pedro Costa, Judd Apatow, David Lean, Orson Welles, Ingmar Bergman, Quentin Tarantino, John Milius, François Truffaut, and Jean-Luc Godard.

From Feeney to Ford

He was born John Martin "Jack" Feeney (though he later often gave his given names as Sean Aloysius, sometimes with surname O'Feeny or O'Fearna; a Gaelic equivalent of Feeney) in Cape Elizabeth, Maine to John Augustine Feeney and Barbara "Abbey" Curran, on February 1, 1894 (though he occasionally said 1895 and that date is erroneously on his tombstone).[1] His father, John Augustine, was born in Spiddal,[3] County Galway, Ireland in 1854.[1] Barbara Curran had been born in the Aran Islands, in the town of Kilronan on the island of Inishmore (Inis Mór).[1]

John A. Feeney's grandmother, Barbara Morris, was said to be a member of a local (impoverished) gentry family, the Morrises of Spiddal, headed at present by Lord Killanin.

John Augustine and Barbara Curran arrived in Boston and Portland respectively within a few days of each other in May and June 1872. They were married in 1875, and became American citizens five years later on September 11, 1880.[1] They had eleven children: Mamie (Mary Agnes), born 1876; Delia (Edith), 1878-1881; Patrick; Francis Ford, 1881-1953; Bridget, 1883-1884; Barbara, born and died 1888; Edward, born 1889; Josephine, born 1891; Hannah (Joanna), born and died 1892; John Martin, 1894-1973; and Daniel, born and died 1896 (or 1898).[1] John Augustine lived in the Munjoy Hill neighborhood of Portland, Maine with his family, and would try farming, fishing, work for the gas company, run a saloon, and be an alderman.[1]

Feeney attended Portland High School, Portland, Maine. He began acting in 1914, taking "Jack Ford" as a stage name. In addition to credited roles, he appeared uncredited as a Klansman in D.W. Griffith's 1915 classic, The Birth of a Nation, as the man who lifts up one side of his hood so he can see clearly.

He married Mary McBryde Smith, on July 3, 1920 and they had two children. Ford never divorced his wife, but he had many extramarital relationships[4] including a tempestuous five-year affair with Katharine Hepburn, whom he met during the filming of Mary of Scotland (1936). The longer revised version of Directed by John Ford shown on Turner Classic Movies in November, 2006 features directors Steven Spielberg, Clint Eastwood, and Martin Scorsese, who suggest that the string of classic films Ford directed 1936-1941 was due in part to his affair with Hepburn.

The private Ford was sensitive, sentimental and erudite but, partly to protect himself in the cutthroat atmosphere of Hollywood, he cultivated the image of a "tough, two-fisted, hard-drinking Irish sonofabitch" (Harry "Dobe" Carey Jr). Although he had many affairs with women, there were occasional rumours about his sexual preferences and in her 2004 autobiography 'Tis Herself, Maureen O'Hara recalled seeing Ford kissing a famous male actor (whom she did not name) on the set of The Long Gray Line.[5]

Director

John Ford began his career in film after moving to California in July 1914. He was following in the footsteps of his multi-talented older brother Francis Ford, twelve years his senior, who had left home years earlier and had worked in vaudeville before becoming a movie actor. Francis played in hundreds of pictures for Thomas Edison, Georges Melies and Thomas Ince, eventually progressing to become a top actor-writer-director with his own production company (101 Bison) at Universal[6].

Jack Ford started out as an assistant/handyman and occasional actor in his brother's films and Francis gave his younger brother his first acting role in The Mysterious Rose (Nov. 1914)[7]. Despite their combative relationship, within three years Jack had progressed to become Francis' chief assistant and often cameraman[8] by which time Francis' profile was declining.

Ford made his directorial debut with the silent two-reeler The Tornado (March 1917); according to Ford's own story, he was given the job by Universal boss Carl Laemmle because, Laemmle said, "he yells good". This was quickly followed by a string of 2- and 3-reelers -- The Trail of Hate, The Scrapper, The Soul Herder and Cheyenne's Pal. Made in the space of a few months, they were typically shot in 2-3 days each, but all are now presumed lost. The Soul Herder is also notable as the beginning of Ford's four-year, 25-film association with veteran writer-actor Harry Carey[9], who (alongside Francis Ford) was a strong early influence on the young director. Carey's son Harry "Dobe" Carey Jr, who also became an actor, was one of Ford's closest friends in later years and featured in many of his most celebrated westerns.

Ford's first feature-length production -- and his earliest surviving film as director -- was Straight Shooting (Aug. 1917). On this film Ford and Carey disobeyed orders and turned in five reels instead of two, and it was only through the intervention of studio head Carl Laemmle that the film escaped being cut for its first release, although it was subsequently cut down to two reels for re-release in the late 1920s[10].

Ford honed his craft on dozens of films over the next decade, including many westerns, but regrettably only a handful of the more than fifty silent features he made for Universal and Fox have survived in any form.[11]. He directed around thirty films in three years at Universal (almost all now lost), before moving to the Fox studio in 1920 and it was during his time at Fox that Ford advanced into the front rank of Hollywood directors. His first film for Fox was Just Pals (1920). His 1923 feature Cameo Kirby, starring John Gilbert -- another of the few surviving Ford silents -- marked his first directing credit under the name "John Ford", rather than "Jack Ford", as he had previously been credited.

With the advent of sound in 1927-28, Ford abandoned the western genre for a decade and became one of the pioneers of the the sound format, directing Fox's first dramatic "talkie" Napoleon's Barber (now lost) and shooting Fox's first song sung on screen, for the film Mother Macree (of which only three of the original seven reels survive). Ford made a wide variety of films in the 1930s including the Expressionist IRA drama The Informer (1935) -- which earned him his first Oscar for Best Director -- the politically charged The Prisoner of Shark Island (1936, Ford's first film with John Carradine), the South Seas melodrama The Hurricane (1937), the Elizabethan costume drama Mary of Scotland (1936) starring Katherine Hepburn, and the light-hearted Shirley Temple vehicle Wee Willie Winkie (1937). During the 1920s, he also served as president of the Motion Picture Directors Association, a forerunner to today's Directors Guild of America.

Ford's classic Stagecoach (1939) was his first western in ten years and his first with sound. This pivotal work ushered in the most successful period of his career and over the next two years he created a string of masterpieces including Young Mr Lincoln, Drums Along The Mohawk, The Grapes of Wrath and How Green Was My Valley. Stagecoach single-handedly revived the moribund Western genre and it was a major critical and commercial success -- it was nominated for seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director, and won two Oscars for Best Supporting Actor (Thomas Mitchell) and Best Score. It was also the first in the series of seven classic Ford Westerns filmed on location in Monument Valley -- Stagecoach, My Darling Clementine (1946), Fort Apache (1948), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), The Searchers (1956), Sergeant Rutledge (1960), and Cheyenne Autumn (1964).

Stagecoach also provided the major career breakthrough Ford's friend John Wayne and Ford is credited with playing a major role in moulding Wayne's image. Over 35 years Wayne appeared in twenty-four of Ford's films (and three TV episodes), including Stagecoach (1939), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), The Quiet Man (1952), The Searchers (1956), The Wings of Eagles (1957), and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962).

Ford's favorite location for his films was in southern Utah's Monument Valley. Ford defined images of the American West with some of the most beautiful and powerful cinematography ever shot, in such films as Stagecoach, The Searchers, Fort Apache, and She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, while the influence on the films of classic Western artists such as Frederic Remington and others has been examined.[12] Ford's evocative use of the territory for his Westerns has defined the images of the American West so powerfully that Orson Welles once said that other film-makers refused to shoot in the region out of fears of plagiarism.[13]

Ford typically exposed only the footage he needed and he often shot in sequence, minimizing the job of his film editors.[14] In the opinion of Joseph McBride [15], his technique of cutting in the camera also enabled him to retain creative control in a period where directors had little say on the editing of their films, because, as Ford noted:

- "I don’t give ‘em a lot of film to play with. In fact, Eastman used to complain that I exposed so little film. I do cut in the camera. Otherwise, if you give them a lot of film ‘the committee’ takes over. They start juggling scenes around and taking out this and putting in that. They can’t do it with my pictures. I cut in the camera and that's it. There's not a lot of film left on the floor when I’m finished."[16]

His good friend Merian C. Cooper, the co-director of King Kong (1933), produced several of Ford's most admired films.

Ford was legendary for his discipline and efficiency on-set[17], and was notorious for being extremely tough on his actors, frequently mocking, yelling and bullying them. He referred to John Wayne as a "big idiot" and even punched an unsuspecting Henry Fonda. Henry Brandon (probably best known as Chief Scar from The Searchers) once referred to Ford as: "The only man who could make John Wayne cry." [citation needed]

However many actors who worked with Ford acknowledged that Ford's often difficult and demanding personality brought out the best in them. John Wayne remarked that "Nobody could handle actors and crew like Jack."[18] And Harry "Dobe" Carey Jr. stated that "He had a quality that made everyone almost kill themselves to please him. Upon arriving on the set, you would feel right away that something special was going to happen. You would feel spiritually awakened all of a sudden." [19] Carey credits John Ford for the inspiration of Carey's final film, Comanche Stallion (2005).

During World War II Commander John Ford, USNR, served in the United States Navy and made documentaries for the Navy Department. He won two more Academy Awards during this time, one for the semi-documentary The Battle of Midway (1942), and a second for the propaganda film December 7th (1943).[20][21][22]

Ford was present on Omaha Beach on D-Day. As head of the photographic unit for the Office of Strategic Services, he crossed the English Channel on the USS Plunkett (DD-431), anchored off Omaha Beach at 0600. He observed the first wave land on the beach from the ship, landing on the beach himself later with a team of US Coast Guard cameramen who filmed the battle from behind the beach obstacles, with Ford directing operations. The film was edited in London, but very little was released to the public. Ford explained in a 1964 interview that the US Government was "afraid to show so many American casualties on the screen", adding that all of the D-Day film "still exists in color in storage in Anacostia near Washington, D.C."[23]. Thirty years later, historian Stephen E. Ambrose reported that the Eisenhower Center had been unable to find the film.[24] Ford eventually rose to become a top adviser to OSS head William Joseph Donovan. According to records released in 2008, Ford was cited by his superiors for bravery, taking a position to film one mission that was "an obvious and clear target." He survived "continuous attack and was wounded" while he continued filming, one commendation in his file states.[25]

After the war, Ford became a Rear Admiral in the United States Navy Reserve.

In 1955, Ford was tapped to direct the classic Navy comedy Mister Roberts, starring Henry Fonda, Jack Lemmon, William Powell, and James Cagney. However, Mervyn LeRoy replaced Ford during filming when he suffered a ruptured gallbladder.

Ford cast Ward Bond as John Dodge, a character based on Ford himself, in the 1957 movie The Wings of Eagles, again starring his good friends John Wayne and Maureen O'Hara.

Ford used many of the same actors repeatedly in his films, far more so than many directors. John Wayne, Henry Fonda, Ben Johnson, Chill Wills, Ward Bond, Grant Withers, Harry Carey, Jr., Ken Curtis, Victor McLaglen, Dolores del Rio, Pedro Armendariz, Woody Strode, Francis Ford (Ford's older brother), Hank Worden, John Qualen, Barry Fitzgerald, Arthur Shields, John Carradine, and Carleton Young were among this group, informally known as the John Ford Stock Company.

Ford died in Palm Desert, California, aged 79 from stomach cancer. He was interred in the Holy Cross Cemetery in Culver City, California. A statue of Ford in Portland, Maine depicts him sitting in a director's chair.

Awards

Ford won four Academy Awards as Best Director for The Informer (1935), The Grapes of Wrath (1940), How Green Was My Valley (1941), and The Quiet Man (1952) - none of them Westerns (also starring in the last two was Maureen O'Hara, "his favorite actress"). He was also nominated as Best Director for Stagecoach (1939). Ford is the only director to have won four Best Director Academy Awards: both William Wyler and Frank Capra won the award three times.

As a producer he received nominations for Best Picture for The Quiet Man and The Long Voyage Home.

He was the first recipient of the American Film Institute Life Achievement Award in 1973. Also in that year, Ford was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Richard Nixon.

In 2007, Twentieth Century Fox released "Ford at Fox", a DVD boxed set of 24 of Ford's films. Time magazine's Richard Corliss named it one of the "Top 10 DVDs of 2007", ranking it at #1. [26]

Academy Awards

The Battle of Midway Academy Award for Documentary Feature

December 7th (film) Academy Award for Documentary Short Subject

Politics

Ford's politics were conventionally progressive as his favorite presidents were Democrats Franklin D. Roosevelt and John F. Kennedy and Republican Abraham Lincoln[27] But despite these leanings, many thought[28][29] he was a Republican because of his long association with actors John Wayne, James Stewart, Maureen O'Hara and Ward Bond. Time magazine editor Whittaker Chambers wrote a harsh review of The Grapes of Wrath as left-wing propaganda, assuming Steinbeck, the author, and Ford to be of that political stripe.

Ford's attitude to McCarthyism in Hollywood is expressed by a story told by Joseph L. Mankiewicz. A faction of the Directors Guild of America led by Cecil B. DeMille had tried to make it mandatory for every member to sign a loyalty oath. A whispering campaign was being conducted against Mankiewicz, then President of the Guild, alleging he had communist sympathies. At a crucial meeting of the Guild, DeMille's faction spoke for four hours until Ford spoke against DeMille and proposed a vote of confidence in Mankiewicz, which was passed. His words were recorded by a court stenographer:

- "My name's John Ford. I make Westerns. I don't think there's anyone in this room who knows more about what the American public wants than Cecil B. DeMille — and he certainly knows how to give it to them.... [looking at DeMille] But I don't like you, C.B. I don't like what you stand for and I don't like what you've been saying here tonight."[30]

However, as time went on, Ford became more publicly allied with the Republican Party, declaring himself a 'Maine Republican' in 1947. He voted for Barry Goldwater in 1964, Richard Nixon in 1968 and became a supporter of the Vietnam War. In 1973, he was awarded the Medal of Freedom by President Nixon, whose campaign he had publicly supported.[31]

Filmography

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h Eyman, Scott. years active:1917-66Print the Legend: The Life and Times of John Ford. New York: Simon & Schuster. 1999. ISBN 0684811618 (excerpt c/o New York Times)

- ^ Gallagher, Tag John Ford: The Man and his Films (University of California Press, 1984), 'Preface'

- ^ Probably better known at the time by its Gaelic name An Spidéal.

- ^ Gallagher, Tag John Ford: The Man and his Films (University of California Press 1984) p.380

- ^ Gallagher, op.cit., p.381

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, p.6

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, p.13

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, p.15

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, p.17

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, p.19

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, pp.502-546

- ^ Peter Cowie, see below

- ^ Welles' narration for the film Directed by John Ford

- ^ BBC Radio 4 programme 10:30am 29 September 2007

- ^ McBride, Joseph, Searching For John Ford: A Life, see below

- ^ Gallagher, Tag, John Ford: The Man and His Films, see below

- ^ Gallagher, 1986, op.cit., p.38

- ^ Eyman, Scott, Print The Legend: The Life and Times of John Ford, see below

- ^ Carey, Harry Jr. Company of Heroes: My Life as an Actor in the John Ford Stock Company

- ^ John Ford - at IMDb

- ^ Biography of Rear Admiral John Ford; U.S. Naval Reserve - at Naval Historical Center

- ^ "Oral History - Battle of Midway:Recollections of Commander John Ford" - at Naval Historical Center

- ^ Martin, Pete, "We Shot D-Day on Omaha Beach (An Interview With John Ford)", The American Legion Magazine, June 1964 from thefilmjournal.com, retrieved 14 February 2007

- ^ Ambrose, Stephen E. D-Day, June 6, 1944: The Climactic Battle of World War II. New York: Simon & Schuster. 1994. pp 395-397. ISBN 0-671-67334-3

- ^ "Spy Tales: a TV Chef, Oscar Winner, JFK Adviser," BRETT J. BLACKLEDGE and RANDY HERSCHAFT, The Associated Press

- ^ Corliss, Richard, "Top 10 DVDs", Time magazine, retrieved from time.com, 14 February 2008

- ^ Peter Bogdanovich, John Ford, See below, pp 18-19.

- ^ Interview with Sam Pollard about Ford and Wayne from pbs.org

- ^ Roger Ebert, "The Grapes of Wrath", 30 March 2002, from rogerebert.com

- ^ Parrish, Robert (1996). "John Ford to the Rescue". Growing up in Hollywood. in Silvester, Christopher (2002), The Grove Book of Hollywood, Grove Press. p. 418. ISBN 0802138780. Retrieved 2008-08-15.

{{cite book}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ McBride, Joseph "The Convoluted Politics of John Ford" Los Angeles Times 3 June 2001[1]

References

- Bogdanovich, Peter. John Ford. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. 1967. Revised 1978. ISBN 0520034988

- Cowie, Peter. John Ford and the American West. New York: Harry Abrams Inc. 2004. ISBN 0810949768

- Eyman, Scott. Print the Legend: The Life and Times of John Ford. New York: Simon & Schuster. 1999. ISBN 0684811618

- Ford, Dan. The Unquiet Man: The Life of John Ford. London: Kimber. 1982 (1979). OCLC 9501332

- Gallagher, Tag. John Ford: The Man and His Films. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. 1986. ISBN 0520050975

- Mitry, Jean. John Ford. 1954.

- McBride, Joseph. Searching for John Ford: A Life. New York: St. Martin's Press. 2001. ISBN 0312242328

- Rollet, Patrice and Saad , Nicolas. John Ford. Paris: Editions de l'Etoile/Cahiers du cinéma : Diffusion, Seuil. 1990. ISBN 2866420934

- Sinclair, Andrew. John Ford. New York: Dial Press/J. Wade. 1979. ISBN 0803748264

External links

- John Ford at IMDb

- John Ford at Find a Grave

- Ford biography - at Yahoo! Movies

- "Ford Till '47" - by Tag Gallagher - at SensesofCinema.com

- "John Ford" - by Richard Franklin - at SensesofCinema.com

- Ford biography (with film poster illustration) - at ReelClassics.com

- Biography of Rear Admiral John Ford; U.S. Naval Reserve - at Naval Historical Center

- "Oral History - Battle of Midway:Recollections of Commander John Ford" - at Naval Historical Center

- John Ford Bibliography - at Film.Virtual-History.com

- "John Ford" - at TheyShootPictures.com

- John Ford document collection - at the Edmonton Public Library

- Talk on Ford in Portland, Maine, by Michael C. Connolly and Kevin Stoehr, editors of John Ford in Focus

Template:Persondata

{{subst:#if:Ford, John|}}

[[Category:{{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:1894}}

|| UNKNOWN | MISSING = Year of birth missing {{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:1973}}||LIVING=(living people)}}

| #default = 1894 births

}}]] {{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:1973}}

|| LIVING = | MISSING = | UNKNOWN = | #default =

}}

- Living people

- 1973 deaths

- American film directors

- American military personnel of World War II

- American Roman Catholics

- Best Director Academy Award winners

- Burials at Holy Cross Cemetery

- Irish-Americans

- Operation Overlord people

- People from Cumberland County, Maine

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Recipients of the Legion of Merit

- Recipients of the Purple Heart medal

- Deaths from stomach cancer

- United States Navy admirals

- Western (genre) film directors

- Cancer deaths in California