Renewable energy commercialization: Difference between revisions

adding Non-tech barriers section |

|||

| Line 84: | Line 84: | ||

Solar power panels that use [[nanotechnology]], which can create circuits out of individual silicon molecules, may cost half as much as traditional photovoltaic cells, according to executives and investors involved in developing the products. [[Nanosolar]], a [[Scatec]] competitor, has secured more than $100 million from investors to build a factory for nanotechnology thin-film solar panels. The Palo Alto, California, company expects the factory to open in 2010 and produce enough solar cells each year to generate 430 megawatts of power.<ref>[http://www.azcentral.com/news/articles/0622-nanotech.html Solar power nanotechnology may cut cost in half, executives say]</ref> |

Solar power panels that use [[nanotechnology]], which can create circuits out of individual silicon molecules, may cost half as much as traditional photovoltaic cells, according to executives and investors involved in developing the products. [[Nanosolar]], a [[Scatec]] competitor, has secured more than $100 million from investors to build a factory for nanotechnology thin-film solar panels. The Palo Alto, California, company expects the factory to open in 2010 and produce enough solar cells each year to generate 430 megawatts of power.<ref>[http://www.azcentral.com/news/articles/0622-nanotech.html Solar power nanotechnology may cut cost in half, executives say]</ref> |

||

==Non-technical barriers to acceptance== |

|||

In September 2006, the U.S. Department of Energy's ''[[Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy]]'' did a review of recent literature discussing the "non-technical barriers" to renewable energy use. These are marketing, institutional, and policy impediments which are holding back the acceptance of renewable energy technologies. These key barriers are listed here, from most frequently cited to least, and "must be addressed as part of the technology acceptance efforts": [http://www.eere.energy.gov/greenpower/markets/pricing.shtml?page=1] |

|||

* Lack of government policy support. This includes the lack of policies and regulations supporting development of renewable energy technologies and the presence of policies and regulations hindering renewable energy development and supporting conventional energy development. Examples include fossil-fuel subsidies, insufficient consumer-based renewable energy incentives, government underwriting for nuclear plant accidents, and difficult zoning and permitting processes for renewable energy. |

|||

* Lack of information dissemination and consumer awareness. |

|||

* High capital cost of renewable energy technologies compared with conventional energy. |

|||

* Difficulty overcoming established energy systems. This includes difficulty introducing innovative energy systems, particularly for distributed generation such as photovoltaics, because of technological lock-in, electricity markets designed for centralized power plants, and market control by established generators. |

|||

*Inadequate financing options for renewable energy projects. |

|||

* Failure to account for all costs and benefits of energy choices. This includes failure to internalize all costs of conventional energy (e.g., effects of air pollution, risk of supply disruption) and failure to internalize all benefits of renewable energy (e.g., cleaner air, energy security). |

|||

* Inadequate workforce skills and training. This includes lack in the workforce of adequate scientific, technical, and manufacturing skills required for renewable energy development; lack of reliable installation, maintenance, and inspection services; and failure of the educational system to provide adequate training in new technologies. |

|||

* Lack of adequate codes, standards, and interconnection and net-metering guidelines. |

|||

* Poor perception by public of renewable energy system aesthetics. |

|||

* Lack of stakeholder/community participation in energy choices and renewable energy projects. |

|||

==Public policy trends== |

==Public policy trends== |

||

Revision as of 01:10, 26 June 2007

| Part of a series on |

| Renewable energy |

|---|

|

Renewable energy technologies are essential contributors to the energy supply portfolio as they generally contribute to world energy security, reducing dependency on fossil fuel resources, and providing opportunities for mitigating greenhouse gases.[1]

Renewable energy encompasses a broad, diverse array of technologies, including solar photovoltaics, solar thermal power plants and heating/cooling systems, wind, hydroelectricity, geothermal, biomass, and ocean power systems. The current status of these different technologies varies considerably. Some technologies are already mature and economically competitive, other technologies need only limited additional development steps to become ready for the market, and yet other technologies are still too expensive and may require a few decades of continued R&D efforts in order to make large contributions on a global scale.[2]

Climate change concerns coupled with high oil prices and increasing government support are driving increasing rates of investment in the renewable energy and energy efficiency industries, according to a trend analysis from the United Nations Environment Programme. The report says investment capital flowing into renewable energy climbed from $80 billion in 2005 to a record $100 billion in 2006.[3]

Three generations of renewable energy technologies

The International Energy Agency has explained that it is possible to define three generations of renewable energy technologies, reaching back more than 100 years:[1]

- First-generation technologies emerged from the industrial revolution at the end of the 19th century and include hydropower, biomass combustion, and geothermal power and heat. Some of these technologies are still in widespread use.

- Second-generation technologies include solar heating and cooling, wind power, modern forms of bioenergy, and solar photovoltaics. These are now entering markets as a result of research, development and demonstration (RD&D) investments since the 1980s. The initial investment was prompted by energy security concerns linked to the oil crises of that period but the continuing appeal of renewables is due, at least in part, to environmental benefits. Many of the technologies reflect significant advancements in materials.

- Third-generation technologies are still under development and include advanced biomass gasification, biorefinery technologies, concentrating solar thermal power, hot-dry-rock geothermal power, and ocean energy. Advances in nanotechnology may also play a major role.[1]

First- and second-generation technologies have entered the markets, and third-generation technologies heavily depend on long term RD&D commitments, where the public sector has a role to play.[1]

First-generation technologies

First-generation technologies are most competitive in locations with abundant resources. Their future use depends on the exploration of the remaining resource potential, particularly in developing countries, and on overcoming challenges related to the environment and social acceptance. For example, there are several significant environmental disadvantages of large-scale hydroelectric power systems, which include: dislocation of people living where the reservoirs are planned, release of significant amounts of carbon dioxide at construction and flooding of the reservoir, and disruption of aquatic ecosystems and birdlife.[4] Hydroelectric power is now more difficult to site in developed nations because most major sites within these nations are either already being exploited or may be unavailable for these environmental reasons (See Hydroelectricity article for details).

Second-generation technologies

Markets for second-generation technologies are strong and growing, mainly in countries such as Germany, Spain, the United States, and Japan. The challenge is to broaden the market base for continued growth worldwide. Strategic deployment in one country not only reduces technology costs for users there, but also for those in other countries, contributing to overall cost reductions and performance improvement.[1] This has been the case for photovoltaics.

Photovoltaics

In the 1980s and early 1990s, most photovoltaic modules provided Remote Area Power Supply, but from around 1995, industry efforts have focused increasingly on developing building integrated photovoltaics and power plants for grid connected applications (see Photovoltaics article for details). There is currently a proposal to build a Solar power station in Victoria, Australia, which would be the world's largest PV power station, at 154MW.[5]

Wind power

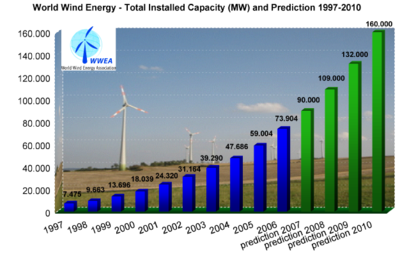

Some of the second-generation renewables, such as wind, have high potential and have already realised relatively low production costs. At the end of 2006, worldwide capacity of wind-powered generators was 74,223 megawatts, and although it currently produces less than 1% of world-wide electricity use, it accounts for approximately 20% of electricity use in Denmark, 9% in Spain, and 7% in Germany.[6][7] However, it may be difficult to site wind turbines in some areas for aesthetic or environmental reasons, and it may be difficult to integrate wind power into electricity grids in some cases.[1]

Solar Heating

Solar heating systems are a well known second-generation technology and are generally composed of solar thermal collectors, a fluid system to move the heat from the collector to its point of usage, and a reservoir or tank for heat storage and subsequent use. The systems may be used to heat domestic hot water, swimming pool water, or for space heating.[8] The heat can also be used for industrial applications or as an energy input for other uses such as cooling equipment.[9] In many climates, a solar heating system can provide a very high percentage (50 to 75%) of domestic hot water energy. In many northern European countries, combined hot water and space heating systems (solar combisystems) are used to provide 15 to 25% of home heating energy (see Solar hot water article).

Bioenergy

Brazil has one of the largest renewable energy programs in the world, involving production of ethanol fuel from sugar cane, and ethanol now provides 18 percent of the country's automotive fuel. As a result, Brazil, which years ago had to import a large share of the petroleum needed for domestic consumption, recently reached complete self-sufficiency in oil.[10] Production and use of ethanol has been stimulated through: (1) low-interest loans for the construction of ethanol distilleries; (2) guaranteed purchase of ethanol by the state-owned oil company at a reasonable price; (3) retail pricing of neat ethanol so it is competitive if not slightly favorable to the gasoline-ethanol blend; and (4) tax incentives provided during the 1980s to stimulate the purchase of neat ethanol vehicles. Guaranteed purchase and price regulation were ended some years ago, with relatively positive results. In addition to these other policies, ethanol producers in the state of Sao Paulo established a research and technology transfer center that has been effective in improving sugar cane and ethanol yields.[11]

Most cars on the road today in the U.S. can run on blends of up to 10% ethanol, and motor vehicle manufacturers already produce vehicles designed to run on much higher ethanol blends. Ford, DaimlerChrysler, and GM are among the automobile companies that sell “flexible-fuel” cars, trucks, and minivans that can use gasoline and ethanol blends ranging from pure gasoline up to 85% ethanol (E85). By mid-2006, there were approximately six million E85-compatible vehicles on U.S. roads.[12] The challenge is to expand the market for biofuels beyond the farm states where they have been most popular to date. Flex-fuel vehicles are assisting in this transition because they allow drivers to choose different fuels based on price and availability. The Energy Policy Act of 2005, which calls for 7.5 billion gallons of biofuels to be used annually by 2012, will also help to expand the market.[13]

It should also be noted that the growing ethanol and biodiesel industries are providing jobs in plant construction, operations, and maintenance, mostly in rural communities. According to the Renewable Fuels Association, the ethanol industry created almost 154,000 U.S. jobs in 2005 alone, boosting household income by $5.7 billion. It also contributed about $3.5 billion in tax revenues at the local, state, and federal levels.[14]

Third-generation technologies

Third-generation technologies are still under development and include advanced biomass gasification, biorefinery technologies, concentrating solar thermal power, hot-dry-rock geothermal power, and ocean energy.[15] Third-generation technologies are not yet widely demonstrated or have limited commercialization. Many are on the horizon and may have potential comparable to other renewable energy technologies, but still depend on attracting sufficient attention and RD&D funding.[16]

New bioenergy technologies

According to the International Energy Agency, new bioenergy (biofuels) technologies being developed today, notably cellulosic ethanol, could allow biofuels to play a much bigger role in the future than previously thought.[17] Cellulosic ethanol can be made from plant matter composed primarily of inedible cellulose fibers that form the stems and branches of most plants. Crop residues (such as corn stalks, wheat straw and rice straw), wood waste, and municipal solid waste are potential sources of cellulosic biomass. Dedicated energy crops, such as switchgrass, are also promising cellulose sources that can be sustainably produced in many regions of the United States.[18]

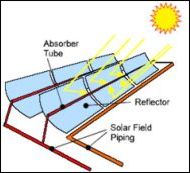

Solar thermal power stations

Solar thermal power stations have been successfully operating in California commercially since the late 1980s, including the largest solar power plant of any kind, the 350 MW Solar Energy Generating Systems. Nevada Solar One is another 64MW plant which has recently opened.[19] Other parabolic trough power plants being proposed are two 50MW plants in Spain (see Solar power in Spain), and a 100MW plant in Israel.[20]

Ocean energy

In terms of Ocean energy, another third-generation technology, Portugal has the world's first commercial wave farm, the Aguçadora Wave Park, established in 2006. The farm will initially use three Pelmis P-750 machines generating 2.25 MW.[21] [22] Initial costs are put at 8.5 million euro. Subject to successful operation, a further 70 million euro is likely to be invested before 2009 on a further 28 machines to generate 525 MW.[23] Funding for a wave farm in Scotland was announced in February, 2007 by the Scottish Executive, at a cost of over 4 million pounds, as part of a £13 million funding packages for ocean power in Scotland. The farm will be the world's largest with a capacity of 3MW generated by four Pelamis machines.[24] (see also Wave farm).

Nanotechnology thin-film solar panels

Solar power panels that use nanotechnology, which can create circuits out of individual silicon molecules, may cost half as much as traditional photovoltaic cells, according to executives and investors involved in developing the products. Nanosolar, a Scatec competitor, has secured more than $100 million from investors to build a factory for nanotechnology thin-film solar panels. The Palo Alto, California, company expects the factory to open in 2010 and produce enough solar cells each year to generate 430 megawatts of power.[25]

Non-technical barriers to acceptance

In September 2006, the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy did a review of recent literature discussing the "non-technical barriers" to renewable energy use. These are marketing, institutional, and policy impediments which are holding back the acceptance of renewable energy technologies. These key barriers are listed here, from most frequently cited to least, and "must be addressed as part of the technology acceptance efforts": [1]

- Lack of government policy support. This includes the lack of policies and regulations supporting development of renewable energy technologies and the presence of policies and regulations hindering renewable energy development and supporting conventional energy development. Examples include fossil-fuel subsidies, insufficient consumer-based renewable energy incentives, government underwriting for nuclear plant accidents, and difficult zoning and permitting processes for renewable energy.

- Lack of information dissemination and consumer awareness.

- High capital cost of renewable energy technologies compared with conventional energy.

- Difficulty overcoming established energy systems. This includes difficulty introducing innovative energy systems, particularly for distributed generation such as photovoltaics, because of technological lock-in, electricity markets designed for centralized power plants, and market control by established generators.

- Inadequate financing options for renewable energy projects.

- Failure to account for all costs and benefits of energy choices. This includes failure to internalize all costs of conventional energy (e.g., effects of air pollution, risk of supply disruption) and failure to internalize all benefits of renewable energy (e.g., cleaner air, energy security).

- Inadequate workforce skills and training. This includes lack in the workforce of adequate scientific, technical, and manufacturing skills required for renewable energy development; lack of reliable installation, maintenance, and inspection services; and failure of the educational system to provide adequate training in new technologies.

- Lack of adequate codes, standards, and interconnection and net-metering guidelines.

- Poor perception by public of renewable energy system aesthetics.

- Lack of stakeholder/community participation in energy choices and renewable energy projects.

Public policy trends

Investment in renewable energy is still very much driven by policy, which today includes a broadening array of tariff and fiscal support regimes in many countries that together create a stable environment globally for continued sector growth.[26] A number of events in 2006 helped push renewable energy up the political agenda, including the US mid-term elections in November, which confirmed clean energy as a mainstream issue. The Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change made a strong economic case for investing in low carbon technologies now, while arguing that economic growth need not be incompatible with cutting energy consumption.[27]

Renewable energy (and energy efficiency) are no longer niche sectors that are promoted only by governments and environmentalists. The increased levels of investment and the fact that much of the capital is coming from more conventional financial actors suggest that sustainable energy options are in fact becoming mainstream.[28]

Corporate trends

Climate change concerns coupled with high oil prices and increasing government support are driving increasing rates of investment in the renewable energy and energy efficiency industries, according to a trend analysis from the United Nations Environment Programme. The report says investment capital flowing into renewable energy climbed from $80 billion in 2005 to a record $100 billion in 2006. In 2007, the upward trend is continuing, with capital investments occurring in sectors and regions previously considered too risky and too illiquid to merit the attention of the institutional investment community.[29]

The OECD still dominates, but there is now increasing activity from companies in China, India and Brazil. Chinese companies were the second largest recipient of venture capital in 2006 after the United States. In the same year, India was the largest net buyer of companies abroad, mostly in the more established European markets.[30]

A recent report from Helmut Kaiser Consultancy of Zurich states that the generation and storage of renewable energy will be the fastest growing sector in energy market over the next 20 years.[31]

The international law firm of Thompson & Knight LLP has launched a Climate Change and Renewable Energy Practice Group, consisting of 26 attorneys. The group will assist businesses worldwide, including those impacted by President George Bush's recent announcement about the administration's new stance on global climate change.[32]

See also

- List of large wind farms

- List of photovoltaics companies

- List of renewable energy topics by country

- List of solar thermal power stations

- List of wind turbine manufacturers

- Deployment of solar power to energy grids

- Eugene Green Energy Standard

- Financial incentives for photovoltaics

- Renewable energy

- Renewable energy commercialization in Australia

- Renewable energy commercialization in the United States

References

- ^ a b c d e f International Energy Agency (2007). Renewables in global energy supply: An IEA facts sheet, OECD, 34 pages.

- ^ "Discussion Paper by the Scientific and Technological Community for the 14th session of the United Nations Commission on Sustainable Development (CSD-14)" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-04-21.

- ^ United Nations Environment Programme and New Energy Finance Ltd. (2007). Global Trends in Sustainable Energy Investment 2007: Analysis of Trends and Issues in the Financing of Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency in OECD and Developing Countries, p. 3

- ^ Hydroelectric power's dirty secret revealed

- ^ Solar Systems projects

- ^ Global wind energy markets continue to boom – 2006 another record year

- ^ European wind companies grow in U.S.

- ^ Solar water heating

- ^ Solar assisted air-conditioning of buildings

- ^ America and Brazil Intersect on Ethanol

- ^ Policies for a More Sustainable Energy Future

- ^ American energy: The renewable path to energy security

- ^ American energy: The renewable path to energy security

- ^ American Energy -- The Renewable Path to Energy Security

- ^ Renewables in global energy supply: An IEA facts sheet

- ^ Renewables in global energy supply: An IEA facts sheet

- ^ International Energy Agency, World Energy Outlook 2006, page 8

- ^ Industrial Biotechnology Is Revolutionizing the Production of Ethanol Transportation Fuel, pages 3-4.

- ^ Solar One is "go" for launch

- ^ Israeli company drives the largest solar plant in the world

- ^ Sea machine makes waves in Europe

- ^ Wave energy contract goes abroad

- ^ Primeiro parque mundial de ondas na Póvoa de Varzim

- ^ Orkney to get 'biggest' wave farm

- ^ Solar power nanotechnology may cut cost in half, executives say

- ^ United Nations Environment Programme and New Energy Finance Ltd. (2007). Global Trends in Sustainable Energy Investment 2007: Analysis of Trends and Issues in the Financing of Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency in OECD and Developing Countries, p. 8

- ^ United Nations Environment Programme and New Energy Finance Ltd. (2007). Global Trends in Sustainable Energy Investment 2007: Analysis of Trends and Issues in the Financing of Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency in OECD and Developing Countries, p. 11

- ^ United Nations Environment Programme and New Energy Finance Ltd. (2007). Global Trends in Sustainable Energy Investment 2007: Analysis of Trends and Issues in the Financing of Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency in OECD and Developing Countries, p. 17

- ^ United Nations Environment Programme and New Energy Finance Ltd. (2007). Global Trends in Sustainable Energy Investment 2007: Analysis of Trends and Issues in the Financing of Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency in OECD and Developing Countries, p. 3

- ^ United Nations Environment Programme and New Energy Finance Ltd. (2007). Global Trends in Sustainable Energy Investment 2007: Analysis of Trends and Issues in the Financing of Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency in OECD and Developing Countries, p. 3

- ^ Renewable Energy Markets Worldwide Driven by Climate Change, Says Swiss Study

- ^ International law firm sets up renewable energy practice group

Bibliography

- International Council for Science (c2006). Discussion Paper by the Scientific and Technological Community for the 14th session of the United Nations Commission on Sustainable Development, 17 pages.

- International Energy Agency, (2006). World Energy Outlook 2006: Summary and Conclusions, OECD, 11 pages.

- International Energy Agency (2007). Renewables in global energy supply: An IEA facts sheet, OECD, 34 pages.

- United Nations Environment Programme and New Energy Finance Ltd. (2007). Global Trends in Sustainable Energy Investment 2007: Analysis of Trends and Issues in the Financing of Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency in OECD and Developing Countries, 52 pages.

- Worldwatch Institute and Center for American Progress (2006). American energy: The renewable path to energy security, 40 pages.

External links

- Sunny outlook for solar power players

- Renewable energy commercialisation in Australia

- Solar Systems to Build A$420 million, 154MW Solar Power Plant in Australia

- BP solar to expand its solar cell plants

- Australia's largest city solar project contract awarded

- Nevada Solar One video

- Windfarms to power a third of London homes

- American energy: The renewable path to energy security

- Distributed Energy -- The Journal for Onsite Power Solutions

- Entrepreneurs Aim To Transform Clean Energy Technology Into Viable Industry

- Investors Pour Unprecedented Billions Into Renewable Energy

- Wind power comes of age