La Brabançonne

| English: The Brabantian | |

|---|---|

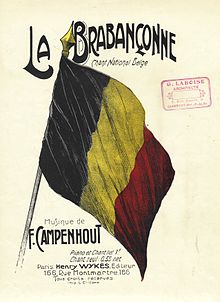

Cover of a score of the Brabançonne, dated around 1910 | |

National anthem of Belgium | |

| Lyrics | Alexandre Dechet and Constantin Rodenbach (original version, 1830) Charles Rogier (current version, 1860) |

| Music | François van Campenhout, September 1830 |

| Adopted | 1860, current text in 1921 |

| Audio sample | |

"La Brabançonne" (instrumental) | |

"La Brabançonne" (French: [la bʁabɑ̃sɔn]; Dutch: "De Brabançonne"; German: "Das Lied von Brabant") is the national anthem of Belgium. The originally-French title refers to Brabant; the name is usually maintained untranslated in Belgium's other two official languages, Dutch and German.[a]

History

According to legend, the Belgian national anthem was written in September 1830, during the Belgian Revolution, by a young revolutionary called "Jenneval", who read the lyrics during a meeting at the Aigle d'Or café.

Jenneval, a Frenchman whose real name was Alexandre Dechet (sometimes known as Louis-Alexandre Dechet), did in fact write the Brabançonne. At the time, he was an actor at the theatre where, in August 1830, the revolution started which led to independence from the Netherlands. Jenneval died in the war of independence. François van Campenhout composed the accompanying score, based on the tune of a French song called "L'Air des lanciers polonais" ("the tune of the Polish Lancers"), written by the French poet Eugène de Pradel, whose tune was itself an adaptation of the tune of a song, "L'Air du magistrat irréprochable", found in a popular collection of drinking songs called La Clé du caveau (The Key to the cellar)[1][2] and it was first performed in September 1830.

In 1860, Belgium formally adopted the song and music as its national anthem, although the then prime minister, Charles Rogier edited out lyrics attacking the Dutch Prince of Orange.

The Brabançonne is also a monument (1930) by the sculptor Charles Samuel on the Surlet de Chokier square in Brussels. The monument contains partial lyrics of both the French and Dutch versions of the anthem. Like many elements in Belgian folklore, this is mainly based on the French "La Marseillaise" which is also both an anthem and the name of a monument – the sculptural group Departure of the Volunteers of 1792, commonly called La Marseillaise, at the base of the Arc de Triomphe in Paris.

Lyrics

1830 original lyrics

First version (August 1830)

Dignes enfants de la Belgique |

Worthy children of the Low Countries[b] |

Second version (September 1830)

Qui l'aurait cru ? ...de l'arbitraire |

Who could have believed it? ... wilfully |

Third version (1860)

Après des siècles et des siècles d'esclavage, |

After century on century in slavery, |

Current version

Various committees were charged with reviewing the text and tune of the Brabançonne and establishing an official version. A ministerial circular of the Ministry of the Interior on 8 August 1921 decreed that only the fourth verse of the text by Charles Rogier should be considered official for all three, French, German and in Dutch. Here below:

- French (La Brabançonne)

Noble Belgique, ô mère chérie, |

Noble Belgium; O, mother dear; |

- Dutch (De Brabançonne)

O dierbaar België, O heilig land der Vaad'ren, |

O dear Belgium; O, holy land of the fathers, |

- German (Die Brabançonne)

O liebes Land, o Belgiens Erde, |

O, dear country; O, Belgium's soil; |

Modern short trilingual version

In recent years, an unofficial short version of the anthem is sung during Belgian National Day on 21 July each year, combining the words of the anthem in all three of Belgium's official languages, similar to the bilingual version of "O Canada". The lyrics are from the 4th verse of the anthem.

| Language | No. | Line | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dutch | 1 | O dierbaar België, O heilig land der Vaad'ren, | O dear Belgium, O holy land of the fathers – |

| 2 | Onze ziel en ons hart zijn u gewijd. | Our soul and our heart are devoted to you! | |

| French | 3 | À toi notre sang, ô Patrie ! | With blood to spill for you, O fatherland! |

| 4 | Nous le jurons tous, tu vivras ! | We swear with one cry – You shall live! | |

| German | 5 | So blühe froh in voller Schöne, | So gladly bloom in beauty full, |

| 6 | zu der die Freiheit Dich erzog, | Into what freedom has taught you to be, | |

| 7 | und fortan singen Deine Söhne: | And evermore shall sing your sons: | |

| French | 8 | Le Roi, la Loi, la Liberté ! | The King, the Law, the Liberty! |

| Dutch | 9 | Het woord getrouw, dat g' onbevreesd moogt spreken, | Faithful to the word that you may speak boldly, |

| 10 | Voor Vorst, voor Vrijheid en voor Recht! | For King, for Freedom and for Law! | |

| German | 11 | Gesetz und König und die Freiheit hoch! | To Law and King and Freedom, hail! |

| French | 12 | Le Roi, la Loi, la Liberté ! | The King, the Law, the Liberty! |

2007 Yves Leterme incident

On the 2007 Belgian national day (21 July), Flemish politician Yves Leterme, who would become Prime Minister two years later, was asked by a French-speaking reporter if he also knew the French lyrics of the Belgian national anthem, whereupon he began to sing La Marseillaise, the French national anthem, instead of La Brabançonne.[3] The lyrics are not taught in Belgian schools and many people do not know them. In 2018, the Minister of Education of Wallonia and Brussels proposed to make it mandatory for students to be taught the lyrics at school.[4]

See also

Notes

- ^ In English, one may refer to Brabant by the adjectives Brabantine or Brabantian, but only the latter term is (nearly) as general as French Brabançonfr, which can also be a substantive for e.g. the dialect, a man, or a horse or its breed from Brabant. In French, Brabançonne is the feminine gender of adjective Brabançon and matches the preceding definite article la, thus might fit an implied e.g. chanson, ('song') (cf. the official name of the French hymn: "la Marseillaise", "(song) having to do with the city of Marseille"). But neither the female definite article in German die Brabançonnede nor the male den Brabançonne in Brabantian or Brabantine dialects of Dutch can fit 'song', which is Lied in German and lied in Dutch, both of neutre genus. In today's standard Dutch, de Brabançonnenl does not betray whether the gender is male or female, but cannot be used for a neuter substantive either, and referring to de Brabançonne by hij confirms the male interpretation of Dutch dialects. For the anthem name in English, as in Dutch, German, and of course French, Brabançonne can be considered a proper noun.

- ^ The Belgian Revolution was not originally separatist, but was a movement for further liberalization of the Netherlands and more rights for French language. The name of "Belgium/Belgia/Belgique" at this time is poetic Latin name of Netherlands and official name of Netherlands in French language.

- ^ At this time was popular symbol of the French Revolution.

- ^ St. Michael the Archangel, a patron saint of Brussels. The image seems to be of the Belgian flag flying from the towers of the Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula, Brussels.

References

- ^ "Courrier des Pays-Bas: La Brabançonne". Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ^ Francis Martens, La Belgique en chantant, pp. 19–40, in Antoine Pickels and Jacques Sojcher (eds.), Belgique: toujours grande et belle, issues 1–2, Éditions Complexe, Brussels, 1998

- ^ "Belgian leader makes anthem gaffe". 23 July 2007 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ Dossantos, Gauvain (20 June 2018). "Apprendre la Brabançonne à l'école, la nouvelle idée de la ministre de l'Éducation". Newsmonkey.

External links

- Belgium: La Brabançonne – Audio of the national anthem of Belgium, with information and lyrics

- Les Arquebusiers History, versions (text and audio) and illustrations

- Belgium National Anthem instrumental File MIDI (5ko)

- Belgium National Anthem instrumental (better) File AU (570ko)

- "La Brabançonne" on YouTube; Helmut Lotti, in French, Dutch and German, before King Albert II