Penicillin: Difference between revisions

→Nomenclature: Added relative potencies of different penicillins |

Deleted old medical usage information and created new section based on FDA labels for penicillin |

||

| Line 58: | Line 58: | ||

<!-- Definition and medical uses --> |

<!-- Definition and medical uses --> |

||

'''Penicillin''' ('''PCN''' or ''' |

'''Penicillin''' ('''P''', '''PCN''' or '''PEN''') is a mixture of natural [[antibiotics]] derived from [[Penicillium]] [[Mold (fungus)|mould]]s (principally, ''[[Penicillium chrysogenum|P. chrysogenum]]'', ''[[Penicillium notatum|P. notatum]]'' and ''[[Penicillium rubens|P. rubens]]''). The two purified natural penicillins in clinical use are [[benzylpenicillin|penicillin G]] ([[Intravenous therapy|intravenous use]]) and [[phenoxymethylpenicillin|penicillin V]] (given by mouth). Penicillin antibiotics were among the first medications to be effective against many [[bacterial infection]]s caused by [[staphylococcus|staphylococci]] and [[streptococcus|streptococci]]. They are still widely used today, though many types of [[bacteria]] have developed [[antibiotic resistance|resistance]] following extensive use. |

||

<!-- Side effects and mechanism --> |

<!-- Side effects and mechanism --> |

||

| Line 149: | Line 149: | ||

A similar standard was also established for penicillin K.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Humphrey JH, Lightbrown JW |title=The international reference preparation of penicillin K. |journal=Bull World Health Organ |year=1954 |volume=10 |page=895–899|PMC=2542178}}</ref> |

A similar standard was also established for penicillin K.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Humphrey JH, Lightbrown JW |title=The international reference preparation of penicillin K. |journal=Bull World Health Organ |year=1954 |volume=10 |page=895–899|PMC=2542178}}</ref> |

||

== |

== Medical usage == |

||

There are only two natural penicillins currently in clinical use: [[penicillin G]] and [[penicillin V]]. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

| ⚫ | Common (≥ 1% of people) [[adverse drug reaction]]s associated with use of the penicillins include [[diarrhoea]], [[hypersensitivity]], [[nausea]], [[rash]], [[neurotoxicity]], [[urticaria]], and [[superinfection]] (including [[candidiasis]]). Infrequent adverse effects (0.1–1% of people) include [[fever]], [[vomiting]], [[erythema]], [[dermatitis]], [[angioedema]], [[seizures]] (especially in people with [[epilepsy]]), and [[pseudomembranous colitis]].<ref name="AMH2006" /> Penicillin can also induce [[serum sickness]] or a [[serum sickness-like reaction]] in some individuals. Serum sickness is a [[type III hypersensitivity]] reaction that occurs one to three weeks after exposure to drugs including penicillin. It is not a true drug allergy, because allergies are [[type I hypersensitivity]] reactions, but repeated exposure to the offending agent can result in an anaphylactic reaction.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Bhattacharya S | title = The facts about penicillin allergy: a review | journal = Journal of Advanced Pharmaceutical Technology & Research | volume = 1 | issue = 1 | pages = 11–7 | date = January 2010 | pmid = 22247826 | pmc = 3255391 | url = https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22247826 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Blumenthal KG, Peter JG, Trubiano JA, Phillips EJ | title = Antibiotic allergy | journal = Lancet | volume = 393 | issue = 10167 | pages = 183–198 | date = January 2019 | pmid = 30558872 | pmc = 6563335 | doi = 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32218-9 | url = https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30558872 }}</ref> Allergy will occur in 1-10% of people, presenting as a skin rash after exposure. IgE-mediated [[anaphylaxis]] will occur in approximately 0.01% of patients.<ref name=":1" /><ref name="AMH2006" /> |

||

|- |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

|- |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

|- |

|||

| [[Penicillin V]], phenoxymethylpenicillin || By mouth || Stable to stomach acid and can be given by mouth. Doses higher than 500 mg cannot be achieved because of poor absorption. |

|||

|} |

|||

| ⚫ | Penicillin G cannot be given by mouth, because it is destroyed by stomach acid. Penicillin G can however be formulated to create insoluble salts. These are then given by intramuscular injection, which creates a depot that slowly releases penicillin G into the body over some weeks. These preparations do not result in chemical modification of penicillin G: these are simply slow-release formulations of penicillin G and are not different sorts of penicillin. There are only two slow-release formulations of penicillin G still in current use: [[Procaine penicillin]] and [[Benzathine benzylpenicillin]]. These are now used only in the treatment of [[syphilis]]. |

||

| ⚫ | Pain and inflammation at the injection site are also common for [[Parenteral#Parenteral by injection or infusion|parenterally]] administered benzathine benzylpenicillin, benzylpenicillin, and, to a lesser extent, procaine benzylpenicillin. The condition is known as [[livedoid dermatitis]] or Nicolau syndrome.<ref>{{cite journal| vauthors = Kim KK, Chae DS |date=2015|title=Nicolau syndrome: A literature review |journal=World Journal of Dermatology |volume=4 |issue=2 |pages=103 |doi=10.5314/wjd.v4.i2.103}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Saputo V, Bruni G | title = [Nicolau syndrome caused by penicillin preparations: review of the literature in search for potential risk factors] | journal = La Pediatria Medica E Chirurgica | volume = 20 | issue = 2 | pages = 105–23 | date = 1998 | pmid = 9706633 }}</ref> |

||

For clinical purposes, penicillin V is used as the oral equivalent of penicillin G. The bioavailability of penicillin V is 60–73% and so for diseases where high blood levels of penicillin are required (for example, [[endocarditis]]), penicillin G injections are required and penicillin V cannot be used. Rapid clearance of penicillin by the kidney mean that both Penicillin G and V must be given four or more times a day in order to maintain a constant blood level of penicillin. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

Penicillin G is licensed for use to treat [[septicaemia]], [[empyema]], [[pneumonia]], [[pericarditis]], |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

[[endocarditis]] and [[meningitis]] caused by susceptible strains of staphylococci and streptococci. It is also licensed for the treatment of |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

[[anthrax]], [[actinomycosis]], cervicofacial disease, thoracic and abdominal disease, [[Clostrodium|clostridial infections]], [[botulism]], [[gas gangrene]] (with accompanying debridement and/or surgery as |

|||

indicated), [[tetanus]] (as an adjunctive therapy to human tetanus |

|||

immune globulin), [[diphtheria]] (as an adjunctive therapy to antitoxin and for |

|||

the prevention of the carrier state), [[erysipelothrix]] endocarditis, [[fusospirochetosis]] (severe infections of the |

|||

[[Vincent’s angina|oropharynx]], lower respiratory tract and genital area), [[Listeria]] infections, meningitis, endocarditis, [[Pasteurella]] infections including bacteraemia and meningitis, [[Haverhill fever]]; [[Rat-bite fever]] and [[Neisseria gonorrhoeae|disseminated gonococcal infections]], [[Neisseria meningitidis|meningococcal]] meningitis and/or septicaemia caused by penicillin-susceptible organisms and [[syphilis]].<ref name="FDA2016">{{cite web|title=Penicillin G Potassium Injection, USP |publisher=US FDA |url=https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/050638s019lbl.pdf |date=July 2016 |access-date=2020-12-28}}</ref> |

|||

Penicillin G is given to treat infections caused by susceptible bacteria. Because penicillin resistance is now so common, testing for susceptibility of penicillin is mandatory to check that penicillin will actually be effective. Penicillin used to be first line treatment for [[Neisseria gonorrhoeae]] and [[Neisseria meningitidis]], but wide-spread resistance means that it is longer recommended for treatment of these infections. Susceptibility testing must be performed by an accredited laboratory to look for penicillin resistance, where possible.<ref name="FDA2016"/> |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

{| class="wikitable" |

||

|- |

|- |

||

! '''Bacterium''' !! '''Susceptible (S)''' !! '''Intermediate (I)''' || '''Resistant (R)''' |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

|- |

|- |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

|- |

|- |

||

| ''[[Streptococcus pneumoniae]]'' [[meningitis]] || ≤0.06 mcg/ml || - || ≥0.12 mcg/ml |

|||

| [[Penicillin V]], phenoxymethylpenicillin || By mouth || It is less active than benzylpenicillin against Gram-negative bacteria. |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''Streptococcus pneumoniae'' (not meningitis) || ≤2 mcg/ml || || ≥8 mcg/ml |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[Streptococcus viridans|''Streptococcus'' Viridans group]] || 0.12 mcg/ml || 0.25–2 mcg/ml || 4 mcg/ml |

|||

|- |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

|- |

|||

| ''[[Bacillus anthracis]]'' || ≤0.12 mcg/ml || - || ≥0.25 mcg/ml |

|||

|} |

|} |

||

== Side effects== |

|||

| ⚫ | Penicillin G cannot be given by mouth, because it is destroyed by stomach acid. Penicillin G can however be formulated to create insoluble salts. These are then given by intramuscular injection, which creates a depot that slowly releases penicillin G into the body over some weeks. These preparations do not result in chemical modification of penicillin G: these are simply slow-release formulations of penicillin G and are not different sorts of penicillin. There are only two slow-release formulations of penicillin G still in current use: [[Procaine penicillin]] and [[Benzathine benzylpenicillin]]. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Common (≥ 1% of people) [[adverse drug reaction]]s associated with use of the penicillins include [[diarrhoea]], [[hypersensitivity]], [[nausea]], [[rash]], [[neurotoxicity]], [[urticaria]], and [[superinfection]] (including [[candidiasis]]). Infrequent adverse effects (0.1–1% of people) include [[fever]], [[vomiting]], [[erythema]], [[dermatitis]], [[angioedema]], [[seizures]] (especially in people with [[epilepsy]]), and [[pseudomembranous colitis]].<ref name="AMH2006" /> Penicillin can also induce [[serum sickness]] or a [[serum sickness-like reaction]] in some individuals. Serum sickness is a [[type III hypersensitivity]] reaction that occurs one to three weeks after exposure to drugs including penicillin. It is not a true drug allergy, because allergies are [[type I hypersensitivity]] reactions, but repeated exposure to the offending agent can result in an anaphylactic reaction.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Bhattacharya S | title = The facts about penicillin allergy: a review | journal = Journal of Advanced Pharmaceutical Technology & Research | volume = 1 | issue = 1 | pages = 11–7 | date = January 2010 | pmid = 22247826 | pmc = 3255391 | url = https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22247826 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Blumenthal KG, Peter JG, Trubiano JA, Phillips EJ | title = Antibiotic allergy | journal = Lancet | volume = 393 | issue = 10167 | pages = 183–198 | date = January 2019 | pmid = 30558872 | pmc = 6563335 | doi = 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32218-9 | url = https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30558872 }}</ref> Allergy will occur in 1-10% of people, presenting as a skin rash after exposure. IgE-mediated [[anaphylaxis]] will occur in approximately 0.01% of patients.<ref name=":1" /><ref name="AMH2006" /> |

||

| ⚫ | Pain and inflammation at the injection site are also common for [[Parenteral#Parenteral by injection or infusion|parenterally]] administered benzathine benzylpenicillin, benzylpenicillin, and, to a lesser extent, procaine benzylpenicillin. The condition is known as [[livedoid dermatitis]] or Nicolau syndrome.<ref>{{cite journal| vauthors = Kim KK, Chae DS |date=2015|title=Nicolau syndrome: A literature review |journal=World Journal of Dermatology |volume=4 |issue=2 |pages=103 |doi=10.5314/wjd.v4.i2.103}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Saputo V, Bruni G | title = [Nicolau syndrome caused by penicillin preparations: review of the literature in search for potential risk factors] | journal = La Pediatria Medica E Chirurgica | volume = 20 | issue = 2 | pages = 105–23 | date = 1998 | pmid = 9706633 }}</ref> |

||

While the number of penicillin-resistant bacteria is increasing, penicillin can still be used to treat a wide range of infections caused by certain susceptible bacteria, including those in the ''[[Streptococcus]]'', ''[[Staphylococcus]]'', ''[[Clostridium]]'', ''[[Neisseria]]'', and ''[[Listeria]]'' genera. The following list illustrates [[minimum inhibitory concentration]] susceptibility data for a few medically significant bacteria:<ref name="Antimicrobial Index">{{cite web |url=http://antibiotics.toku-e.com/antimicrobial_914_18.html |title=Penicillin (Benzylpenicillin, Penicillin G, Bicillin C-R/L-A, Pfizerpen, Wycellin) |work=The Antimicrobial Index |publisher=Knowledgebase |access-date=4 March 2014}}</ref><ref name="TOKU-E">{{cite web |url=http://www.toku-e.com/Assets/MIC/Penicillin%20G%20sodium%20salt.pdf |title=Penicillin G sodium salt Susceptibility and Resistance Data |publisher=TOKU-E |access-date=4 March 2014}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

* ''Neisseria meningitidis'': from less than or equal to 0.03 μg/ml to 0.5 μg/ml |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | The natural penicillins are produced by by Penicillium species and are used in the clinic without chemical modification. Different natural penicillins are produced by changing the culture media used to grow the Penicillium mould. There are only two natural penicillins currently in widespread medical use, and these are: |

||

* [[Penicillin G]] |

|||

* [[Penicillin V]] |

|||

None of other natural penicillins (F, K, N, O, U1 |

None of other natural penicillins (F, K, N, X, O, U1 or U6) are currently in clinical use. |

||

===Semi-synthetic penicillins=== |

===Semi-synthetic penicillins=== |

||

Revision as of 13:02, 28 December 2020

Penicillin core structure, where "R" is the variable group | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Micromedex Detailed Consumer Information |

| Routes of administration | Intravenous, intramuscular, by mouth |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | Between 0.5 and 56 hours |

| Excretion | Kidneys |

Penicillin (P, PCN or PEN) is a mixture of natural antibiotics derived from Penicillium moulds (principally, P. chrysogenum, P. notatum and P. rubens). The two purified natural penicillins in clinical use are penicillin G (intravenous use) and penicillin V (given by mouth). Penicillin antibiotics were among the first medications to be effective against many bacterial infections caused by staphylococci and streptococci. They are still widely used today, though many types of bacteria have developed resistance following extensive use.

About 10% of people report that they are allergic to penicillin; however, up to 90% of this group may not actually be allergic.[2] Serious allergies only occur in about 0.03%.[2] Those who are allergic to penicillin are most often given cephalosporin C because there is only 10% crossover in allergy between the penicillins and cephalosporins.[3] All penicillins are β-lactam antibiotics, which are some of the most powerful and successful achievements in modern science.[3]

Penicillin was discovered in 1928 by Scottish scientist Alexander Fleming.[4] Penicillin was first used to treat infections in 1942.[5] Fleming shared the 1945 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his discovery, along with Oxford University scientists Howard Florey and Ernst Boris Chain (who developed improved ways to produce and concentrate the drug and prove its antibacterial effects).

There are several semi-synthetic penicillins which are effective against a broader spectrum of bacteria: these include the antistaphylococcal penicillins, aminopenicillins and the antipseudomonal penicillins.

Nomenclature

The term "penicillin" is defined as the natural product of Penicillium mould with antimicrobial activity.[6] In modern usage, the term penicillin is used more broadly to refer to any beta-lactam antimicrobial that contains a thiazolidine ring fused to the beta-lactam core, and may or may not be a natural product.[7]

Like most natural products, penicillin is a mixture of active constituents (gentamicin is another example of a natural product that is an ill-defined mixture of active components).[6] The principal active components of penicillin are listed in the following table.[8][9]

| Chemical name | UK nomenclature | US nomenclature | Relative potency[10] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-pentenylpenicillin | penicillin I | penicillin F[11] | 70–82% |

| benzylpenicillin | penicillin II | penicillin G[12] | 100% (reference) |

| p-hydroxybenzylpenicillin | penicillin III | penicillin X[13] | 130–140% |

| N-heptylpenicillin | penicillin IV | penicillin K[14] | 110–120% |

Other minor active components of penicillin include penicillin O,[15][16] penicillin U1 and penicillin U6. Other named constituents of natural penicillin, such as penicillin A, were subsequently found not to have antibiotic activity and are not chemically related to penicillin.[6]

The precise constitution of the penicillin extracted depends on the species of Penicillium mould used and on the nutrient media used to culture the mould.[6] Fleming's original strain of Penicillium rubens produces principally Penicillin F, but Penicillin F is unstable and difficult to isolate. Penicillin F was named 'F' for Alexander Fleming.[6]

The principal commercial strain of Penicillium chrysogenum (the Peoria strain) produces penicillin G as the principle component when corn steep liquor is used as the culture medium.[6] When phenoxyethanol is added to the culture medium, the mould produces penicillin V as the main penicillin instead.[6]

6-aminopenicillanic acid (6-APA) is a compound derived from penicillin G. 6-APA contains the beta-lactam core of penicillin G, but with the side chains stripped off; 6-APA is a useful precursor for manufacturing other penicillins. There are a number of semi-synthetic penicillins derived from 6-APA and these are in three groups: antistaphylococcal penicillins, broad-spectrum penicillins and antipseudomonal penicillins. The semi-synthetic penicillins are all referred to as penicillins, because they are all derived ultimately from penicillin G.

Penicillin units

- One unit of penicillin G is defined as 0.600 micrograms. Therefore, 2 million units (2 megaunits) of penicillin G is 1.2 g.[17]

- One unit of penicillin V is defined as 0.625 micrograms. Therefore 400,000 units of penicillin V is 250 mg.[18]

The use of units to prescribe penicillin is an historical accident and is largely obsolete outside of the US. Since the original penicillin was an ill-defined mixture of active compounds (an amorphous yellow powder), the potency of each batch of penicillin varied from batch to batch. It was therefore impossible to prescribe 1 g of penicillin, because the activity of 1 g of penicillin from one batch would be different from the activity from another batch. After manufacture, each batch of penicillin had to be standardised against a known unit of penicillin: each glass vial was then filled with the number of units required. In the 1940's, a vial of 5,000 Oxford units was standard,[19] but the depending on the batch, could contain anything from 15 mg to 20 mg of penicillin. Later, a vial of 1,000,000 international units became standard, and this could contain 2.5 g to 3 g of natural penicillin (a mixture of penicillin I, II, III and IV and natural impurities). With the advent of pure penicillin G preparations (a white crystalline powder), there is little reason to prescribe penicillin in units.

The "unit" of penicillin has had three previous definitions, and each definition was chosen as being roughly equivalent to the previous one.

- Oxford or Florey unit (1941). This was originally defined as the minimum amount of penicillin dissolved in 50 ml of meat extract that would inhibit the growth of a standard strain of Staphylococcus aureus (the Oxford Staphylococcus). The reference standard was a large batch of impure penicillin kept in Oxford. The assay was later modified by Florey's group to a more reproducible "cup assay": in this assay, a penicillin solution was defined to contain one unit/ml of penicillin when 339 microlitres of the solution placed in a "cup" on a plate of solid agar produced a 24 millimetre zone of inhibition of growth of Oxford Staphylococcus.[20]: 107 [21][22]

- First International Standard (1944). A single large standard batch of pure crystalline penicillin was stored at The National Institute for Medical Research at Mill Hill in London (the International Standard). One penicillin unit was defined at 0.6 micrograms of the International Standard. An impure "working standard" was also defined and was available in much larger quantities distributed around the world: one unit of the working standard was 2.7 micrograms (the amount per unit was much larger because of the impurities). At the same time, the cup assay was refined, where instead of specifying a zone diameter of 24 mm, the zone size were instead plotted against a reference curve to provide a readout on potency.[22][8][23][22]

- Second International Standard (1953). A large standard batch of pure crystalline penicillin G was obtained: this was also stored at Mill Hill. One penicillin unit was defined as 0.5988 micrograms of the Second International Standard.[24]

There is an older unit for penicillin V that is not equivalent to the current penicillin V unit. The reason is because the US FDA incorrectly assumed that the potency of penicillin V is the same mole-for-mole as penicillin G. In fact, penicillin V is less potent than penicillin G, and the current penicillin V unit reflects that fact.

- First international unit of penicillin V (1959). One unit of penicillin V was defined as 0.590 micrograms of a reference standard held at Mill Hill in London. [25] This unit is now obsolete.

A similar standard was also established for penicillin K.[26]

Medical usage

There are only two natural penicillins currently in clinical use: penicillin G and penicillin V.

| Names | Method of administration | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Penicillin G, benzylpenicillin | IV or IM | Not stable to stomach acid and cannot be taken by mouth. Doses as high as 2.4 g can be achieved. |

| Penicillin V, phenoxymethylpenicillin | By mouth | Stable to stomach acid and can be given by mouth. Doses higher than 500 mg cannot be achieved because of poor absorption. |

Penicillin G cannot be given by mouth, because it is destroyed by stomach acid. Penicillin G can however be formulated to create insoluble salts. These are then given by intramuscular injection, which creates a depot that slowly releases penicillin G into the body over some weeks. These preparations do not result in chemical modification of penicillin G: these are simply slow-release formulations of penicillin G and are not different sorts of penicillin. There are only two slow-release formulations of penicillin G still in current use: Procaine penicillin and Benzathine benzylpenicillin. These are now used only in the treatment of syphilis.

For clinical purposes, penicillin V is used as the oral equivalent of penicillin G. The bioavailability of penicillin V is 60–73% and so for diseases where high blood levels of penicillin are required (for example, endocarditis), penicillin G injections are required and penicillin V cannot be used. Rapid clearance of penicillin by the kidney mean that both Penicillin G and V must be given four or more times a day in order to maintain a constant blood level of penicillin.

Penicillin G is licensed for use to treat septicaemia, empyema, pneumonia, pericarditis, endocarditis and meningitis caused by susceptible strains of staphylococci and streptococci. It is also licensed for the treatment of anthrax, actinomycosis, cervicofacial disease, thoracic and abdominal disease, clostridial infections, botulism, gas gangrene (with accompanying debridement and/or surgery as indicated), tetanus (as an adjunctive therapy to human tetanus immune globulin), diphtheria (as an adjunctive therapy to antitoxin and for the prevention of the carrier state), erysipelothrix endocarditis, fusospirochetosis (severe infections of the oropharynx, lower respiratory tract and genital area), Listeria infections, meningitis, endocarditis, Pasteurella infections including bacteraemia and meningitis, Haverhill fever; Rat-bite fever and disseminated gonococcal infections, meningococcal meningitis and/or septicaemia caused by penicillin-susceptible organisms and syphilis.[27]

Penicillin G is given to treat infections caused by susceptible bacteria. Because penicillin resistance is now so common, testing for susceptibility of penicillin is mandatory to check that penicillin will actually be effective. Penicillin used to be first line treatment for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis, but wide-spread resistance means that it is longer recommended for treatment of these infections. Susceptibility testing must be performed by an accredited laboratory to look for penicillin resistance, where possible.[27]

| Bacterium | Susceptible (S) | Intermediate (I) | Resistant (R) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | ≤0.12 mcg/ml | - | ≥0.25 mcg/ml |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis | ≤0.06 mcg/ml | - | ≥0.12 mcg/ml |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae (not meningitis) | ≤2 mcg/ml | ≥8 mcg/ml | |

| Streptococcus Viridans group | 0.12 mcg/ml | 0.25–2 mcg/ml | 4 mcg/ml |

| Listeria monocytogenes | ≤2 mcg/ml | - | - |

| Bacillus anthracis | ≤0.12 mcg/ml | - | ≥0.25 mcg/ml |

Side effects

Common (≥ 1% of people) adverse drug reactions associated with use of the penicillins include diarrhoea, hypersensitivity, nausea, rash, neurotoxicity, urticaria, and superinfection (including candidiasis). Infrequent adverse effects (0.1–1% of people) include fever, vomiting, erythema, dermatitis, angioedema, seizures (especially in people with epilepsy), and pseudomembranous colitis.[28] Penicillin can also induce serum sickness or a serum sickness-like reaction in some individuals. Serum sickness is a type III hypersensitivity reaction that occurs one to three weeks after exposure to drugs including penicillin. It is not a true drug allergy, because allergies are type I hypersensitivity reactions, but repeated exposure to the offending agent can result in an anaphylactic reaction.[29][30] Allergy will occur in 1-10% of people, presenting as a skin rash after exposure. IgE-mediated anaphylaxis will occur in approximately 0.01% of patients.[31][28]

Pain and inflammation at the injection site are also common for parenterally administered benzathine benzylpenicillin, benzylpenicillin, and, to a lesser extent, procaine benzylpenicillin. The condition is known as livedoid dermatitis or Nicolau syndrome.[32][33]

Members

The penicillins can be divided in to two broad classes: the natural penicillins and the semi-synthetic penicillins.

Natural penicillins

The natural penicillins are produced by by Penicillium species and are used in the clinic without chemical modification. Different natural penicillins are produced by changing the culture media used to grow the Penicillium mould. There are only two natural penicillins currently in widespread medical use, and these are:

None of other natural penicillins (F, K, N, X, O, U1 or U6) are currently in clinical use.

Semi-synthetic penicillins

There are three major groups of semi-synthetic penicillin: these are all synthesised from 6-APA as an intermediate. These are the antistaphylococcal penicillins, the broad-spectrum penicillins and the antipseudomonal penicillins.

Antistaphylococcal penicillins

- Cloxacillin (by mouth or by injection)

- Dicloxacillin (by mouth or by injection)

- Flucloxacillin (by mouth or by injection)

- Methicillin (injection only)

- Nafcillin (injection only)

- Oxacillin (by mouth or by injection)

The antistaphylococcal penicillins are so called, because they are resistant to being broken down by Staphylococcal penicillinase. They are also therefore referred to as penicillinase-resistant penicillins or β-lactamase-resistant penicillins.

Broad-spectrum penicillins

The broad-spectrum penicillins are so called, because they are active against Gram-negative organisms such as Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhi, which are not usually susceptible to penicillin. However, resistance in these organisms is now common.

There are a number of ampicillin precursors in existence. These are inactive compounds that are broken down in the gut to release ampicillin. None of these pro-drugs of ampicillin are in current use:

- Pivampicillin (pivaloyloxymethyl ester of ampicillin)

- Bacampicillin

- Metampicillin (formaldehyde ester of ampicillin)

- Talampicillin

- Hetacillin (ampicillin conjugated to acetone)

Epicillin is an aminopenicillin that has never seen widespread clinical use.

Antipseudomonal penicillins

The Gram-negative organism, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, is naturally resistant to many antibiotic classes. There were many efforts in the 1960's and 1970's to develop penicillins that are active against Pseudomonas species. There are two chemical classes within the group: carboxypenicillins and ureidopenicillins. All are given by injection: none can be given by mouth.

Carboxypenicillins

Ureidopenicillins

β-lactamase inhibitors

Pharmacology

Penicillin inhibits activity of enzymes that are needed for the cross linking of peptidoglycans in bacterial cell walls, which is the final step in cell wall biosynthesis. It does this by binding to penicillin binding proteins with the beta-lactam ring, a structure found on penicillin molecules.[34][35] This causes the cell wall to weaken due to fewer cross links and means water uncontrollably flows into the cell because it cannot maintain the correct osmotic gradient. This results in cell lysis and death.

Some bacteria produce enzymes that break down the beta-lactam ring, called beta-lactamases, which make the bacteria resistant to penicillin. Therefore, some penicillins are modified or given with other drugs for use against antibiotic-resistant bacteria or in immunocompromised patients. Use of clavulanic acid or tazobactam, beta-lactamase inhibitors, alongside penicillin gives penicillin activity against beta-lactamase-producing bacteria. Beta-lactamase inhibitors irreversibly bind to beta-lactamase preventing it from breaking down the beta-lactam rings on the antibiotic molecule. Alternatively, flucloxacillin is a modified penicillin that has activity against beta-lactamase-producing bacteria due to an acyl side chain that protects the beta-lactam ring from beta-lactamase.[31]

Mechanism of action

Bacteria constantly remodel their peptidoglycan cell walls, simultaneously building and breaking down portions of the cell wall as they grow and divide. β-Lactam antibiotics inhibit the formation of peptidoglycan cross-links in the bacterial cell wall; this is achieved through binding of the four-membered β-lactam ring of penicillin to the enzyme DD-transpeptidase. As a consequence, DD-transpeptidase cannot catalyze formation of these cross-links, and an imbalance between cell wall production and degradation develops, causing the cell to rapidly die.[37]

The enzymes that hydrolyze the peptidoglycan cross-links continue to function, even while those that form such cross-links do not. This weakens the cell wall of the bacterium, and osmotic pressure becomes increasingly uncompensated—eventually causing cell death (cytolysis). In addition, the build-up of peptidoglycan precursors triggers the activation of bacterial cell wall hydrolases and autolysins, which further digest the cell wall's peptidoglycans. The small size of the penicillins increases their potency, by allowing them to penetrate the entire depth of the cell wall. This is in contrast to the glycopeptide antibiotics vancomycin and teicoplanin, which are both much larger than the penicillins.[38]

Gram-positive bacteria are called protoplasts when they lose their cell walls. Gram-negative bacteria do not lose their cell walls completely and are called spheroplasts after treatment with penicillin.[36]

Penicillin shows a synergistic effect with aminoglycosides, since the inhibition of peptidoglycan synthesis allows aminoglycosides to penetrate the bacterial cell wall more easily, allowing their disruption of bacterial protein synthesis within the cell. This results in a lowered MBC for susceptible organisms.[39]

Penicillins, like other β-lactam antibiotics, block not only the division of bacteria, including cyanobacteria, but also the division of cyanelles, the photosynthetic organelles of the glaucophytes, and the division of chloroplasts of bryophytes. In contrast, they have no effect on the plastids of the highly developed vascular plants. This supports the endosymbiotic theory of the evolution of plastid division in land plants.[40]

The chemical structure of penicillin is triggered with a very precise, pH-dependent directed mechanism, effected by a unique spatial assembly of molecular components, which can activate by protonation. It can travel through bodily fluids, targeting and inactivating enzymes responsible for cell-wall synthesis in gram-positive bacteria, meanwhile avoiding the surrounding non-targets. Penicillin can protect itself from spontaneous hydrolysis in the body in its anionic form while storing its potential as a strong acylating agent, activated only upon approach to the target transpeptidase enzyme and protonated in the active centre. This targeted protonation neutralizes the carboxylic acid moiety, which is weakening of the β-lactam ring N–C(=O) bond, resulting in a self-activation. Specific structural requirements are equated to constructing the perfect mouse trap for catching targeted prey.[41]

Pharmacokinetics

Penicillin has low protein binding in plasma. The bioavailability of penicillin depends on the type: penicillin G has low bioavailability, below 30%, whereas penicillin V has higher bioavailability, between 60 and 70%. Penicillin has a short half life and is excreted via the kidneys.[42]

Structure

The term "penam" is used to describe the common core skeleton of a member of the penicillins. This core has the molecular formula R-C9H11N2O4S, where R is the variable side chain that differentiates the penicillins from one another. The penam core has a molar mass of 243 g/mol, with larger penicillins having molar mass near 450—for example, cloxacillin has a molar mass of 436 g/mol. The key structural feature of the penicillins is the four-membered β-lactam ring; this structural moiety is essential for penicillin's antibacterial activity. The β-lactam ring is itself fused to a five-membered thiazolidine ring. The fusion of these two rings causes the β-lactam ring to be more reactive than monocyclic β-lactams because the two fused rings distort the β-lactam amide bond and therefore remove the resonance stabilisation normally found in these chemical bonds.[43]

History

Discovery

Starting in the late 19th century there had been reports of the antibacterial properties of Penicillium mould, but scientists were unable to discern what process was causing the effect.[44] Scottish physician Alexander Fleming at St Mary's Hospital in London (now part of Imperial College) was the first to show that Penicillium rubens had antibacterial properties in 1928.[45] On 3 September 1928 he observed that fungal contamination of a bacterial culture (Staphylococcus aureus) appeared to kill the bacteria. He confirmed this observation with a new experiment on 28 September 1928.[46] He published his experiment in 1929, and called the antibacterial substance (the fungal extract) penicillin.[47]

C. J. La Touche identified the fungus as Penicillium rubrum (later reclassified by Charles Thom as P. notatum and P. chrysogenum, but later corrected as P. rubens).[48] Fleming expressed initial optimism that penicillin would be a useful antiseptic, because of its high potency and minimal toxicity in comparison to other antiseptics of the day, and noted its laboratory value in the isolation of Bacillus influenzae (now called Haemophilus influenzae).[49][50]

Fleming did not convince anyone that his discovery was important.[49] This was largely because penicillin was so difficult to isolate that its development as a drug seemed impossible. It is speculated that had Fleming been more successful at making other scientists interested in his work, penicillin would possibly have been developed years earlier.[49]

The importance of his work has been recognized by the placement of an International Historic Chemical Landmark at the Alexander Fleming Laboratory Museum in London on November 19, 1999.[51]

Medical application

In 1930, Cecil George Paine, a pathologist at the Royal Infirmary in Sheffield, successfully treated ophthalmia neonatorum, a gonococcal infection in infants, with penicillin (fungal extract) on November 25, 1930.[52][53][54]

In 1940, Australian scientist Howard Florey (later Baron Florey) and a team of researchers (Ernst Boris Chain, Edward Abraham, Arthur Duncan Gardner, Norman Heatley, Margaret Jennings, J. Orr-Ewing and G. Sanders) at the Sir William Dunn School of Pathology, University of Oxford made progress in making concentrated penicillin from fungal culture broth that showed both in vitro and in vivo bactericidal action.[55][56] In 1941, they treated a policeman, Albert Alexander, with a severe face infection; his condition improved, but then supplies of penicillin ran out and he died. Subsequently, several other patients were treated successfully.[57] In December 1942, survivors of the Cocoanut Grove fire in Boston were the first burn patients to be successfully treated with penicillin.[58]

Mass production

As the medical application was established, the Oxford team found that it was impossible to produce usable amounts in their laboratory.[57] In 1941, Florey and Heatley travelled to the US in order to interest pharmaceutical companies in producing the drug and inform them about their process.[57]

On March 14, 1942, the first patient was treated for streptococcal sepsis with US-made penicillin produced by Merck & Co.[59] Half of the total supply produced at the time was used on that one patient, Anne Miller.[60] By June 1942, just enough US penicillin was available to treat ten patients.[61] In July 1943, the War Production Board drew up a plan for the mass distribution of penicillin stocks to Allied troops fighting in Europe.[62] The results of fermentation research on corn steep liquor at the Northern Regional Research Laboratory at Peoria, Illinois, allowed the United States to produce 2.3 million doses in time for the invasion of Normandy in the spring of 1944. After a worldwide search in 1943, a mouldy cantaloupe in a Peoria, Illinois market was found to contain the best strain of mould for production using the corn steep liquor process.[63] Pfizer scientist Jasper H. Kane suggested using a deep-tank fermentation method for producing large quantities of pharmaceutical-grade penicillin.[64][20]: 109 Large-scale production resulted from the development of a deep-tank fermentation plant by chemical engineer Margaret Hutchinson Rousseau.[65] As a direct result of the war and the War Production Board, by June 1945, over 646 billion units per year were being produced.[62]

G. Raymond Rettew made a significant contribution to the American war effort by his techniques to produce commercial quantities of penicillin, wherein he combined his knowledge of mushroom spawn with the function of the Sharples Cream Separator.[66] By 1943, Rettew's lab was producing most of the world's penicillin. During World War II, penicillin made a major difference in the number of deaths and amputations caused by infected wounds among Allied forces, saving an estimated 12%–15% of lives.[citation needed] Availability was severely limited, however, by the difficulty of manufacturing large quantities of penicillin and by the rapid renal clearance of the drug, necessitating frequent dosing. Methods for mass production of penicillin were patented by Andrew Jackson Moyer in 1945.[67][68][69] Florey had not patented penicillin, having been advised by Sir Henry Dale that doing so would be unethical.[57]

Penicillin is actively excreted, and about 80% of a penicillin dose is cleared from the body within three to four hours of administration. Indeed, during the early penicillin era, the drug was so scarce and so highly valued that it became common to collect the urine from patients being treated, so that the penicillin in the urine could be isolated and reused.[70] This was not a satisfactory solution, so researchers looked for a way to slow penicillin excretion. They hoped to find a molecule that could compete with penicillin for the organic acid transporter responsible for excretion, such that the transporter would preferentially excrete the competing molecule and the penicillin would be retained. The uricosuric agent probenecid proved to be suitable. When probenecid and penicillin are administered together, probenecid competitively inhibits the excretion of penicillin, increasing penicillin's concentration and prolonging its activity. Eventually, the advent of mass-production techniques and semi-synthetic penicillins resolved the supply issues, so this use of probenecid declined.[70] Probenecid is still useful, however, for certain infections requiring particularly high concentrations of penicillins.[28][needs update]

After World War II, Australia was the first country to make the drug available for civilian use. In the U.S., penicillin was made available to the general public on March 15, 1945.[71]

Fleming, Florey and Chain shared the 1945 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with for the development of penicillin.

Structure determination and total synthesis

The chemical structure of penicillin was first proposed by Edward Abraham in 1942[55] and was later confirmed in 1945 using X-ray crystallography by Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin, who was also working at Oxford.[72] She later received the Nobel prize for this and other structure determinations.

Chemist John C. Sheehan at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) completed the first chemical synthesis of penicillin in 1957.[73][74][75] Sheehan had started his studies into penicillin synthesis in 1948, and during these investigations developed new methods for the synthesis of peptides, as well as new protecting groups—groups that mask the reactivity of certain functional groups.[75][76] Although the initial synthesis developed by Sheehan was not appropriate for mass production of penicillins, one of the intermediate compounds in Sheehan's synthesis was 6-aminopenicillanic acid (6-APA), the nucleus of penicillin.[75][77][78][page needed] Attaching different groups to the 6-APA 'nucleus' of penicillin allowed the creation of new forms of penicillin.

Developments from penicillin

The narrow range of treatable diseases or "spectrum of activity" of the penicillins, along with the poor activity of the orally active phenoxymethylpenicillin, led to the search for derivatives of penicillin that could treat a wider range of infections. The isolation of 6-APA, the nucleus of penicillin, allowed for the preparation of semisynthetic penicillins, with various improvements over benzylpenicillin (bioavailability, spectrum, stability, tolerance).

The first major development was ampicillin in 1961. It offered a broader spectrum of activity than either of the original penicillins. Further development yielded β-lactamase-resistant penicillins, including flucloxacillin, dicloxacillin, and methicillin. These were significant for their activity against β-lactamase-producing bacterial species, but were ineffective against the methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains that subsequently emerged.[79]

Another development of the line of true penicillins was the antipseudomonal penicillins, such as carbenicillin, ticarcillin, and piperacillin, useful for their activity against Gram-negative bacteria. However, the usefulness of the β-lactam ring was such that related antibiotics, including the mecillinams, the carbapenems and, most important, the cephalosporins, still retain it at the center of their structures.[80]

Production

Penicillin is a secondary metabolite of certain species of Penicillium and is produced when growth of the fungus is inhibited by stress. It is not produced during active growth. Production is also limited by feedback in the synthesis pathway of penicillin.[citation needed]

The by-product, l-lysine, inhibits the production of homocitrate, so the presence of exogenous lysine should be avoided in penicillin production.

The Penicillium cells are grown using a technique called fed-batch culture, in which the cells are constantly subject to stress, which is required for induction of penicillin production. The available carbon sources are also important: glucose inhibits penicillin production, whereas lactose does not. The pH and the levels of nitrogen, lysine, phosphate, and oxygen of the batches must also be carefully controlled.[citation needed]

The biotechnological method of directed evolution has been applied to produce by mutation a large number of Penicillium strains. These techniques include error-prone PCR, DNA shuffling, ITCHY, and strand-overlap PCR.

Semisynthetic penicillins are prepared starting from the penicillin nucleus 6-APA.

Biosynthesis

Overall, there are three main and important steps to the biosynthesis of penicillin G (benzylpenicillin).

- The first step is the condensation of three amino acids—L-α-aminoadipic acid, L-cysteine, L-valine into a tripeptide.[81][82][83] Before condensing into the tripeptide, the amino acid L-valine must undergo epimerization to become D-valine.[84][85] The condensed tripeptide is named δ-(L-α-aminoadipyl)-L-cysteine-D-valine (ACV). The condensation reaction and epimerization are both catalyzed by the enzyme δ-(L-α-aminoadipyl)-L-cysteine-D-valine synthetase (ACVS), a nonribosomal peptide synthetase or NRPS.

- The second step in the biosynthesis of penicillin G is the oxidative conversion of linear ACV into the bicyclic intermediate isopenicillin N by isopenicillin N synthase (IPNS), which is encoded by the gene pcbC.[81][82] Isopenicillin N is a very weak intermediate, because it does not show strong antibiotic activity.[84]

- The final step is a transamidation by isopenicillin N N-acyltransferase, in which the α-aminoadipyl side-chain of isopenicillin N is removed and exchanged for a phenylacetyl side-chain. This reaction is encoded by the gene penDE, which is unique in the process of obtaining penicillins.[81]

See also

References

- ^ Walling AD (September 15, 2006). "Tips from Other Journals – Antibiotic Use During Pregnancy and Lactation". American Family Physician. 74 (6): 1035. Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- ^ a b Gonzalez-Estrada A, Radojicic C (May 2015). "Penicillin allergy: A practical guide for clinicians". Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 82 (5): 295–300. doi:10.3949/ccjm.82a.14111. PMID 25973877. S2CID 6717270.

- ^ a b Kardos N, Demain AL (November 2011). "Penicillin: the medicine with the greatest impact on therapeutic outcomes". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 92 (4): 677–87. doi:10.1007/s00253-011-3587-6. PMID 21964640. S2CID 39223087.

- ^ "Discovery and Development of Penicillin". American Chemical Society. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ^ Oxford Handbook of Infectious Diseases and Microbiology. OUP Oxford. 2009. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-19-103962-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g Robinson FA (1947). "Chemistry of penicillin". Analyst. 72 (856): 274–6. doi:10.1039/an9477200274. PMID 20259048.

- ^ Patrick GL (2017). Medicinal Chemistry (6th ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 425. ISBN 978-0198749691.

- ^ a b "Recommendations of the International Conference on Penicillin". Science. Vol. 101, no. 2611. 1945-01-12. pp. 42–43. doi:10.1126/science.101.2611.42.

- ^ Committee on Medical Research, O.S.R.D., Washington, and the Medical Research Council, London (1945). "Chemistry of Penicillin". Science. 102 (2660): 627–629. doi:10.1126/science.102.2660.627.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Harry Eagle (1946). "The relative activity of penicillins F, G, K, and X against spirochetes and streptococci in vitro". J Bacteriol. 52 (1): 81–88. PMC 518141. PMID 16561156.

- ^ "Penicillin F". PubChem. National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 2020-12-26.

- ^ "Penicillin G". PubChem. National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 2020-12-26.

- ^ "Penicillin X". PubChem. National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 2020-12-26.

- ^ "Penicillin K". PubChem. National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 2020-12-26.

- ^ "Penicillin O". PubChem. National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 2020-12-26.

- ^ Fishman LS, Hewitt WL (September 1970). "The natural penicillins". The Medical Clinics of North America. 54 (5): 1081–99. doi:10.1016/S0025-7125(16)32579-2. PMID 4248661.

- ^ Genus Pharmaceuticals (2020-11-30). "Benzylpenicillin sodium 1200mg Powder for Injection". Electronic medicines compendium. Datapharm Ltd. Retrieved 2020-12-28.

- ^ Sandoz GmbH. "Penicillin-VK" (PDF). US FDA. Retrieved 2020-12-28.

- ^ "Penicillin, 5,000 Oxford Units". National Museum of American History. Behring Center, Washington, D. C. Retrieved 2020-12-28.

- ^ a b Greenwood D (2008). "Antimicrobial Drugs: A Chronicle of a Twentieth Century Medical Triumph". Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-19-953484-5.

- ^ Abraham EP, Chain E, Fletcher CM, Gardner AD, Heatley NG, Jennings MA, Florey HW (1941). "Further observations on penicillin". Lancet. 238 (6155): 177–189. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)72122-2.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Foster JW, Woodruff HB (1943). "Microbiological aspects of penicillin. I. Methods of assay". J Bacteriol. 46 (2): 187–202. PMC 373803. PMID 16560688.

- ^ Hartley P (1945). "World standard and unit for penicillin". Science. 101 (2634): 637–638. doi:10.1126/science.101.2634.637.

- ^ Humphrey JH, Musset MV, Perry WL (1953). "The second international standard for penicillin". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 9 (1): 15–28. PMC 2542105. PMID 13082387.

- ^ Humphrey KH, Lightbrown JW, Musset MV (1959). "International standard for phenoxymethylpenicillin". Bull World Health Organ. 20: 1221–1227.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Humphrey JH, Lightbrown JW (1954). "The international reference preparation of penicillin K." Bull World Health Organ. 10: 895–899. PMC 2542178.

- ^ a b "Penicillin G Potassium Injection, USP" (PDF). US FDA. July 2016. Retrieved 2020-12-28.

- ^ a b c Rossi S, ed. (2006). Australian Medicines Handbook. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook. ISBN 978-0-9757919-2-9.

- ^ Bhattacharya S (January 2010). "The facts about penicillin allergy: a review". Journal of Advanced Pharmaceutical Technology & Research. 1 (1): 11–7. PMC 3255391. PMID 22247826.

- ^ Blumenthal KG, Peter JG, Trubiano JA, Phillips EJ (January 2019). "Antibiotic allergy". Lancet. 393 (10167): 183–198. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32218-9. PMC 6563335. PMID 30558872.

- ^ a b Hitchings A, Lonsdale D, Burrage D, Baker E (2015). Top 100 drugs : clinical pharmacology and practical prescribing. pp. 174–181. ISBN 978-0-7020-5516-4.

- ^ Kim KK, Chae DS (2015). "Nicolau syndrome: A literature review". World Journal of Dermatology. 4 (2): 103. doi:10.5314/wjd.v4.i2.103.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Saputo V, Bruni G (1998). "[Nicolau syndrome caused by penicillin preparations: review of the literature in search for potential risk factors]". La Pediatria Medica E Chirurgica. 20 (2): 105–23. PMID 9706633.

- ^ Yocum RR, Rasmussen JR, Strominger JL (May 1980). "The mechanism of action of penicillin. Penicillin acylates the active site of Bacillus stearothermophilus D-alanine carboxypeptidase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 255 (9): 3977–86. PMID 7372662.

- ^ "Benzylpenicillin". www.drugbank.ca. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ a b Cushnie TP, O'Driscoll NH, Lamb AJ (December 2016). "Morphological and ultrastructural changes in bacterial cells as an indicator of antibacterial mechanism of action". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 73 (23): 4471–4492. doi:10.1007/s00018-016-2302-2. hdl:10059/2129. PMID 27392605. S2CID 2065821.

- ^ Gordon E, Mouz N, Duée E, Dideberg O (June 2000). "The crystal structure of the penicillin-binding protein 2x from Streptococcus pneumoniae and its acyl-enzyme form: implication in drug resistance". Journal of Molecular Biology. 299 (2): 477–85. doi:10.1006/jmbi.2000.3740. PMID 10860753.

- ^ Van Bambeke F, Lambert D, Mingeot-Leclercq MP, Tulkens P (1999). Mechanism of Action (PDF).

- ^ Winstanley TG, Hastings JG (February 1989). "Penicillin-aminoglycoside synergy and post-antibiotic effect for enterococci". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 23 (2): 189–99. doi:10.1093/jac/23.2.189. PMID 2708179.

- ^ Kasten B, Reski R (March 30, 1997). "β-lactam antibiotics inhibit chloroplast division in a moss (Physcomitrella patens) but not in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum)". Journal of Plant Physiology. 150 (1–2): 137–140. doi:10.1016/S0176-1617(97)80193-9.

- ^ Mucsi Z, Chass GA, Ábrányi-Balogh P, Jójárt B, Fang DC, Ramirez-Cuesta AJ, et al. (December 2013). "Penicillin's catalytic mechanism revealed by inelastic neutrons and quantum chemical theory". Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 15 (47): 20447–20455. Bibcode:2013PCCP...1520447M. doi:10.1039/c3cp50868d. PMID 23760063.

- ^ Levison ME, Levison JH (December 2009). "Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antibacterial agents". Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 23 (4): 791–815, vii. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2009.06.008. PMC 3675903. PMID 19909885.

- ^ Nicolaou (1996), pg. 43.

- ^ Dougherty TJ, Pucci MJ (2011). Antibiotic Discovery and Development. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 79–80.

- ^ Landau R, Achilladelis B, Scriabine A (1999). Pharmaceutical Innovation: Revolutionizing Human Health. Chemical Heritage Foundation. p. 162.

- ^ Haven KF (1994). Marvels of Science: 50 Fascinating 5-Minute Reads. Littleton, CO: Libraries Unlimited. p. 182. ISBN 978-1-56308-159-0.

- ^ Fleming A (1929). "On the Antibacterial Action of Cultures of a Penicillium, with Special Reference to their Use in the Isolation of B. influenzæ". British Journal of Experimental Pathology. 10 (3): 226–236. PMC 2048009. Reprinted as Fleming A (1980). "Classics in infectious diseases". Reviews of Infectious Diseases. 2 (1): 129–39. doi:10.1093/clinids/2.1.129. PMC 2041430. PMID 6994200.

- ^ Houbraken J, Frisvad JC, Samson RA (June 2011). "Fleming's penicillin producing strain is not Penicillium chrysogenum but P. rubens". IMA Fungus. 2 (1): 87–95. doi:10.5598/imafungus.2011.02.01.12. PMC 3317369. PMID 22679592.

- ^ a b c Lax E (2004). The Mold in Dr. Florey's Coat: The Story of the Penicillin Miracle. Holt Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-8050-7778-0.

- ^ Krylov AK (1991). "Gastroenterologic aspects of the clinical picture of internal diseases". Terapevticheskii Arkhiv. 63 (2): 139–41. PMID 2048009.

- ^ "Discovery and Development of Penicillin". International Historic Chemical Landmarks. American Chemical Society. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- ^ Wainwright M, Swan HT (January 1986). "C.G. Paine and the earliest surviving clinical records of penicillin therapy". Medical History. 30 (1): 42–56. doi:10.1017/S0025727300045026. PMC 1139580. PMID 3511336.

- ^ Howie J (July 1986). "Penicillin: 1929-40". British Medical Journal. 293 (6540): 158–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.293.6540.158. PMC 1340901. PMID 3089435.

- ^ Wainwright M (January 1987). "The history of the therapeutic use of crude penicillin". Medical History. 31 (1): 41–50. doi:10.1017/s0025727300046305. PMC 1139683. PMID 3543562.

- ^ a b Jones DS, Jones JH (2014-12-01). "Sir Edward Penley Abraham CBE. 10 June 1913 – 9 May 1999". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 60: 5–22. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2014.0002. ISSN 0080-4606.

- ^ "Ernst B. Chain – Nobel Lecture: The Chemical Structure of the Penicillins". www.nobelprize.org. Retrieved 2017-05-10.

- ^ a b c d "Making Penicillin Possible: Norman Heatley Remembers". ScienceWatch. Thomson Scientific. 2007. Archived from the original on February 21, 2007. Retrieved 2007-02-13.

- ^ Levy SB (2002). The Antibiotic Paradox: How the Misuse of Antibiotics Destroys Their Curative Powers. Da Capo Press. pp. 5–7. ISBN 978-0-7382-0440-6.

- ^ Grossman CM (July 2008). "The first use of penicillin in the United States". Annals of Internal Medicine. 149 (2): 135–6. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-149-2-200807150-00009. PMID 18626052. S2CID 40197907.

- ^ Rothman L (14 March 2016). "Penicillin history: what happened to first American patient". Time. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ^ Mailer JS, Mason B. "Penicillin : Medicine's Wartime Wonder Drug and Its Production at Peoria, Illinois". lib.niu.edu. Retrieved February 11, 2008.

- ^ a b Parascandola J (1980). The History of antibiotics: a symposium. American Institute of the History of Pharmacy No. 5. ISBN 978-0-931292-08-8.

- ^ Bellis M. "The History of Penicillin". Inventors. About.com. Retrieved October 30, 2007.

- ^ Lehrer S (2006). Explorers of the Body: Dramatic Breakthroughs in Medicine from Ancient Times to Modern Science (2nd ed.). New York: iUniverse. pp. 329–330. ISBN 978-0-595-40731-6.

- ^ Madhavan G (Aug 20, 2015). Think Like an Engineer. Oneworld Publications. pp. 83–85, 91–93. ISBN 978-1-78074-637-1. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ^ "G. Raymond Rettew Historical Marker". ExplorePAhistory.com. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ^ US 2442141, Moyer AJ, "Method for Production of Penicillin", issued 25 March 1948, assigned to US Agriculture

- ^ US 2443989, Moyer AJ, "Method for Production of Penicillin", issued 22 June 1948, assigned to US Agriculture

- ^ US 2476107, Moyer AJ, "Method for Production of Penicillin", issued 12 July 1949, assigned to US Agriculture

- ^ a b Silverthorn DU (2004). Human physiology: an integrated approach (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River (NJ): Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0-8053-5957-2.

- ^ "Discovery and development of penicillin". American Chemical Society. 1999.

- ^ The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1964, Perspectives. Retrieved July 14, 2012.

- ^ Sheehan JC, H enery-Logan KR (March 5, 1957). "The Total Synthesis of Penicillin V". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 79 (5): 1262–1263. doi:10.1021/ja01562a063.

- ^ Sheehan JC, Henery-Loganm KR (June 20, 1959). "The Total Synthesis of Penicillin V". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 81 (12): 3089–3094. doi:10.1021/ja01521a044.

- ^ a b c Corey EJ, Roberts JD. "Biographical Memoirs: John Clark Sheehan". The National Academy Press. Retrieved January 28, 2013.

- ^ Nicolaou KC, Vourloumis D, Winssinger N, Baran PS (January 2000). "The Art and Science of Total Synthesis at the Dawn of the Twenty-First Century". Angewandte Chemie. 39 (1): 44–122. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(20000103)39:1<44::AID-ANIE44>3.0.CO;2-L. PMID 10649349.

- ^ "Professor John C. Sheehan Dies at 76". MIT News. April 1, 1992. Retrieved January 28, 2013.

- ^ Sheehan JC (1982). The Enchanted Ring: The Untold Story of Penicillin. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-19204-0.

- ^ Colley EW, Mcnicol MW, Bracken PM (March 1965). "Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococci in a General Hospital". Lancet. 1 (7385): 595–7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(65)91165-7. PMID 14250094.

- ^ James CW, Gurk-Turner C (January 2001). "Cross-reactivity of beta-lactam antibiotics". Proceedings. 14 (1): 106–7. doi:10.1080/08998280.2001.11927741. PMC 1291320. PMID 16369597.

- ^ a b c Al-Abdallah Q, Brakhage AA, Gehrke A, Plattner H, Sprote P, Tuncher A (2004). "Regulation of Penicillin Biosynthesis in Filamentous Fungi". In Brakhage AA (ed.). Molecular Biotechnology of Fungal beta-Lactam Antibiotics and Related Peptide Synthetases. Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology. Vol. 88. pp. 45–90. doi:10.1007/b99257. ISBN 978-3-540-22032-9. PMID 15719552.

- ^ a b Brakhage AA (September 1998). "Molecular regulation of beta-lactam biosynthesis in filamentous fungi". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 62 (3): 547–85. doi:10.1128/MMBR.62.3.547-585.1998. PMC 98925. PMID 9729600.

- ^ Schofield CJ, Baldwin JE, Byford MF, Clifton I, Hajdu J, Hensgens C, Roach P (December 1997). "Proteins of the penicillin biosynthesis pathway". Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 7 (6): 857–64. doi:10.1016/s0959-440x(97)80158-3. PMID 9434907.

- ^ a b Martín JF, Gutiérrez S, Fernández FJ, Velasco J, Fierro F, Marcos AT, Kosalkova K (September 1994). "Expression of genes and processing of enzymes for the biosynthesis of penicillins and cephalosporins". Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 65 (3): 227–43. doi:10.1007/BF00871951. PMID 7847890. S2CID 25327312.

- ^ Baker WL, Lonergan GT (December 2002). "Chemistry of some fluorescamine–amine derivatives with relevance to the biosynthesis of benzylpenicillin by fermentation". Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology: International Research in Process, Environmental & Clean Technology. 77 (12): 1283–8. doi:10.1002/jctb.706.

Further reading

- Nicolaou KC, Corey EJ (1996). Classics in Total Synthesis : Targets, Strategies, Methods (5. repr. ed.). Weinheim: VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-29284-4.

- Dürckheimer W, Blumbach J, Lattrell R, Scheunemann KH (March 1, 1985). "Recent Developments in the Field of β-Lactam Antibiotics". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 24 (3): 180–202. doi:10.1002/anie.198501801.

- Hamed RB, Gomez-Castellanos JR, Henry L, Ducho C, McDonough MA, Schofield CJ (January 2013). "The enzymes of β-lactam biosynthesis". Natural Product Reports. 30 (1): 21–107. doi:10.1039/c2np20065a. PMID 23135477.

External links

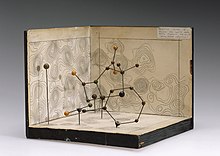

- Model of Structure of Penicillin, by Dorothy Hodgkin et al., Museum of the History of Science, Oxford

- The Discovery of Penicillin, A government produced film about the discovery of Penicillin by Sir Alexander Fleming, and the continuing development of its use as an antibiotic by Howard Florey and Ernst Boris Chain on YouTube.

- Penicillin at The Periodic Table of Videos (University of Nottingham)

- Penicillin Released to Civilians Will Cost $35 Per Patient Popular Science, August 1944, article at bottom of page