Coat of arms of France: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

|use= |

|use= |

||

}} |

}} |

||

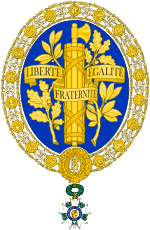

The '''coat of arms of France''' depicts a fasces surrounded by wreaths of laurel and oak, as well as a ribbon bearing the national motto ''[[Liberté, égalité, fraternité]]''. |

The '''coat of arms of France''' depicts a fasces surrounded by wreaths of laurel and oak, as well as a ribbon bearing the national motto ''[[Liberté, égalité, fraternité]]''. Introduced in 1905, this [[heraldry|heraldic]] emblem has been used by the [[French Third Republic|third]], [[French Fourth Republic|fourth]] and [[French Fifth Republic|fifth]] republic, with one notable change occuring in 1953, when the design of the grand colar of the [[Legion of Honour]] was changed. The arms follows the ''[[fleur-de-lis]]'' designs used by French kings since the Middle Ages, which were followed by the [[House of Bonaparte|Napoleonic]] eagle designs after the [[French Revolution]]. The [[fleur-de-lis]] is still popular, and used by overseas people of French heritage, like the [[Acadians]], [[French-speaking Quebecer|Québécois]] or [[Cajun]]s. |

||

, [[French Fourth Republic|Fourth]] and [[French Fifth Republic|Fifth]] Republic |

|||

| 1905–1953 (greater version), 1905–present (escutcheon) |

|||

|align="center" |[[File:Arms of the French Republic.svg|120px]] |

|||

|align="center"| [[File:Middle coat of arms of the French Republic (1905–1953).svg|150px]] |

|||

|Between 1905 and 1953, the middle version of the present coat of arms displayed the 1881 version of the grand collar of the [[Legion of Honour]]. |

|||

|} |

|||

==Design== |

==Design== |

||

Revision as of 21:19, 21 November 2020

| Coat of arms of France | |

|---|---|

| |

| Versions | |

| |

Monochrome (hatched) version | |

Monochrome (hatched) achievement (1905 design) | |

| Armiger | French Republic[3] |

| Adopted | 1905 (1953 with present collar)[4] |

| Crest | Wreath |

| Shield | Azure, a Fasces surrounded by on the dexter, a wreath of laurel, and to the sinister, a wreath of Oak, over all a ribbon bearing the motto Liberté, égalité, fraternité, all Or. |

| Supporters | Angels |

| Compartment | Wheat, weapons, flowers and musical instruments |

| Order(s) | Collar of the Legion of Honour (1953 version) |

| Other elements | All surrounded by wheat mantling, Cockade of France, Flag of France, flowers |

The coat of arms of France depicts a fasces surrounded by wreaths of laurel and oak, as well as a ribbon bearing the national motto Liberté, égalité, fraternité. Introduced in 1905, this heraldic emblem has been used by the third, fourth and fifth republic, with one notable change occuring in 1953, when the design of the grand colar of the Legion of Honour was changed. The arms follows the fleur-de-lis designs used by French kings since the Middle Ages, which were followed by the Napoleonic eagle designs after the French Revolution. The fleur-de-lis is still popular, and used by overseas people of French heritage, like the Acadians, Québécois or Cajuns.

, Fourth and Fifth Republic

| 1905–1953 (greater version), 1905–present (escutcheon)

|align="center" | |align="center"|

|align="center"|  |Between 1905 and 1953, the middle version of the present coat of arms displayed the 1881 version of the grand collar of the Legion of Honour.

|}

|Between 1905 and 1953, the middle version of the present coat of arms displayed the 1881 version of the grand collar of the Legion of Honour.

|}

Design

The blazoning is:

Azure, a Fasces surrounded by on the dexter, a wreath of laurel, and to the sinister, a wreath of Oak, over all a ribbon bearing the motto Liberté, égalité, fraternité, all Or.

The achievement also includes the grand collar of the Legion of Honour, which is worn only by the President of the Republic, as Grand Master of the order.

Motto

The national motto, Liberté, égalité, fraternité

Liberté, égalité, fraternité (French pronunciation: [libɛʁte eɡalite fʁatɛʁnite]), French for "liberty, equality, fraternity",[5] is the national motto of France and the Republic of Haiti, and is an example of a tripartite motto. Although it finds its origins in the French Revolution, it was then only one motto among others and was not institutionalized until the Third Republic at the end of the 19th century.[6] Debates concerning the compatibility and order of the three terms began at the same time as the Revolution. It is also the motto of the Grand Oriente and the Grande Loge de France.

Fasces

Fasces, like many other symbols of the French Revolution, are Roman in origin. Fasces are a bundle of birch rods containing a sacrificial axe. In Roman times, the fasces symbolized the power of magistrates, representing union and accord with the Roman Republic. The French Republic continued this Roman symbol to represent state power, justice, and unity.[7]

During the Revolution, the fasces image was often used in conjunction with many other symbols. Though seen throughout the French Revolution, perhaps the most well known French reincarnation of the fasces is the Fasces surmounted by a Phrygian cap. This image has no display of an axe or a strong central state; rather, it symbolizes the power of the liberated people by placing the Liberty Cap on top of the classical symbol of power.[7]

A review of the images included in Les Grands Palais de France : Fontainebleau[8][9] reveals that French architects used the Roman fasces (faisceaux romains) as a decorative device as early as the reign of Louis XIII (1610–1643) and continued to employ it through the periods of Napoleon I's Empire (1804–1815).

The fasces typically appeared in a context reminiscent of the Roman Republic and of the Roman Empire. The French Revolution used many references to the ancient Roman Republic in its imagery. During the First Republic, topped by the Phrygian cap, the fasces is a tribute to the Roman Republic and means that power belongs to the people. It also symbolizes the "unity and indivisibility of the Republic",[10] as stated in the French Constitution. In 1848 and after 1870, it appears on the seal of the French Republic, held by the figure of Liberty. There is the fasces in the arms of the French Republic with the "RF" for République française (see image below), surrounded by leaves of olive tree (as a symbol of peace) and oak (as a symbol of justice). While it is used widely by French officials, this symbol never was officially adopted by the government.[10]

The fasces appears on the helmet and the buckle insignia of the French Army's Autonomous Corps of Military Justice, as well as on that service's distinct cap badges for the prosecuting and defending lawyers in a court-martial.[citation needed]

Wreath of oak

- Wreath of oak

The oak is a common symbol of strength and endurance and has been chosen as the national tree of many countries. In England, oaks have been a national symbol since at least the sixteenth century, often used by Shakespeare to confer heritage and power. In England today they remain a symbol of the nation's history, traditions, and the beauty of its countryside. Already an ancient Germanic symbol (in the form of the Donar Oak, for instance), certainly since the early nineteenth century, it stands for the nation of Germany and oak branches are thus displayed on some German coins, both of the former Deutsche Mark and the current euro currency.[11] In 2004 the Arbor Day Foundation[12] held a vote for the official National Tree of the United States of America. In November 2004, the United States Congress passed legislation designating the oak as America's National Tree.[13]

Other countries have also designated the oak as their national tree including Bulgaria, Cyprus (golden oak), Estonia, France, Germany, Moldova, Jordan, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Serbia, and Wales.[14]

The oak is the emblem of County Londonderry in Northern Ireland, as a vast amount of the county was covered in forests of the tree until relatively recently. The name of the county comes from the city of Derry, which originally in Irish was known as Doire meaning "oak".

The Irish County Kildare derives its name from the town of Kildare which originally in Irish was Cill Dara meaning the Church of the Oak or Oak Church.

Iowa designated the oak as its official state tree in 1961; and the white oak is the state tree of Connecticut, Illinois and Maryland. The northern red oak is the provincial tree of Prince Edward Island, as well as the state tree of New Jersey. The live oak is the state tree of the US state of Georgia.

The oak is a national symbol from the Basque Country, specially in the province of Biscay.

The oak is a symbol of the East Bay of the San Francisco Bay Area; the coat-of-arms and flag of Oakland, California feature the oak and the logo of the East Bay Regional Park District is an oak leaf.

The coats-of-arms of Vest-Agder, Norway, and Blekinge, Sweden, feature oak trees.

The coat-of-arms of the municipality Eigersund, Norway features an oak leaf.

Oak leaves are traditionally an important part of German Army regalia.[citation needed] The Nazi party used the traditional German eagle, standing atop of a swastika inside a wreath of oak leaves. It is also known as the Iron Eagle. During the Third Reich of Nazi Germany, oak leaves were used for military valor decoration on the Knights Cross of the Iron Cross. They also symbolize rank in the United States Armed Forces. A gold oak leaf indicates an O-4 (major or lieutenant commander), whereas a silver oak leaf indicates an O-5 (lieutenant colonel or commander). Arrangements of oak leaves, acorns and sprigs indicate different branches of the United States Navy staff corps officers.[15] Oak leaves are embroidered onto the covers (hats) worn by field grade officers and flag officers in the United States armed services.

If a member of the United States Army or Air Force earns multiple awards of the same medal, then instead of wearing a ribbon or medal for each award, he or she wears one metal representation of an "oak leaf cluster" attached to the appropriate ribbon for each subsequent award.[16]

The oak tree is used as a symbol by a number of political parties. It is the symbol of Toryism (on account of the Royal Oak) and the Conservative Party in the United Kingdom,[17] and formerly of the Progressive Democrats in Ireland[18] and the Democrats of the Left in Italy. In the cultural arena, the oakleaf is the symbol of the National Trust (UK), The Woodland Trust, and The Royal Oak Foundation.[15]

Wreath of laurel

Elements:

In heraldry, a twisted band of cloth holds a mantling onto a helmet.[19] This type of charge is called a "torse".[19] A wreath is a circlet of foliage, usually with leaves, but sometimes with flowers.[19] Laurel wreaths are used the arms of a territorial branch. [19] Wreaths may also be made from oak leaves, flowers, holly and rosemary; and are different from chaplets. While usually annular, they may also be penannular like a brooch.[19]

Order

The achievement also includes the grand collar of the Legion of Honour, which is worn only by the President of the Republic, as Grand Master of the order.

The Legion of Honour[a] (French: Légion d'honneur, IPA: [leʒjɔ̃ dɔnœʁ]) is the highest French order of merit for military and civil merits, established in 1802 by Napoleon Bonaparte and retained by all later French governments and régimes.

The order's motto is Honneur et Patrie ("Honour and Fatherland"), and its seat is the Palais de la Légion d'Honneur next to the Musée d'Orsay, on the left bank of the Seine in Paris.[b]

The order is divided into five degrees of increasing distinction: Chevalier (Knight), Officier (Officer), Commandeur (Commander), Grand officier (Grand Officer), and Grand-croix (Grand Cross).

-

1953 version of the grand collar

-

Achievement between 1905 and 1953, depicting the 1881 version of the grand collar

History

Timeline of usage

| External image | |

|---|---|

-

The arms adorning the Foreign Ministry on the 1905 Spanish royal visit

-

The national coat of arms (left) displayed on the Church of Saint Nicholas of the Lorrainers in Rome, dedicated to France, seen in 2014

- 1905: The arms was introduced as a national symbol at the occasion of King Alfonso XIII's official visit to France. It was displayed on the steps of the king's residence and at the French foreign ministry.[23][24]

- 1925: A greater version of the arms was depicted on a painted tapestry by Gustave Louis Jaulmes, titled "Les armes de France". Commissioned by the city of Strasbourg,[25] this piece was to be installed at the Commissariat General of the Republic in the city.

- 1928: German encyclopedias gave a color reproduction of Jaulmes' greater arms.

- 1929: On 10 May the German embassy in France inquired what was the official coat of arms of France was. The French Ministry of Foreign Affairs replied that "there is no, in principle, official coat of arms or emblem," but that such a composition was used for the French embassies and consulates.

- 1935: The annual edition of Le Petit Larousse reproduced a monochrome reproduction of the arms as a symbol of the French Republic.

- 1953: The United Nations Secretariat requested that France submit a national coat of arms that were to adorn the wall behind the podium in the General Assembly hall in New York, alongside the other member states' arms. On 3 June, an interministerial commission met at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to select this emblem. It requested Robert Louis (1902–1965), heraldic artist, to produce a version of the Jules-Clément Chaplain design. In the end, Louis chose the 1905 design.

- 1975: President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing adopted the charge of the arms in his presidential standard.

- 6 June 1980: President d'Estaing assumed on him being admitted to the Order of the Seraphim: Azure a Fasces Or bindings Argent between two Laurel sprigs disposed orleways of the second and bound together in base by a ribbon of the third., based on the republican arms.

- 2009: Used to represent France in the Hanseatic Fountain in Veliky Novgorod, Russia.[26]

The coat of arms is still used, e.g. in relation to presidential inaugurations, including that of François Mitterrand, Jacques Chirac and Emmanuel Macron in 1981, 1995 and 2017, respectively.[27][28]

Previous designs

| Period | Dates used | Coat of arms | Achievement | Banner of arms | Description and blazon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

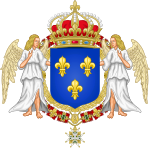

| Kingdom | Before 1305 |

|

|

|

The arms of France Ancient: Azure semé-de-lis or The historical coat of arms of France were the golden fleurs-de-lys on a blue field, used continuously for nearly six centuries (1211–1792). Although according to legend they originated at the baptism of Clovis, who supposedly replaced the three toads that adorned his shield with three lilies given by an angel, they are first documented only from the early 13th century. They were first shown as semé, that is to say without any definite number and staggered (known as France ancient), but in 1376 they were reduced to three, (known as France modern). With this decision, King Charles V intended to place the kingdom under the double invocation of the Virgin (the lily is a symbol of Mary), and the Trinity, for the number. The traditional supporters of the French royal arms are two angels, sometimes wearing a heraldic dalmatic. |

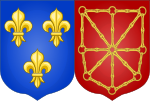

| 1305–1328 |

|

|

? | Arms of France Ancient dimidiated with the arms of Navarre, after king Louis X inherited Navare from his mother Joan I of Navarre in 1305. | |

| 1328–1376 |

|

|

|

The arms of France Ancient: Azure semé-de-lis or. After the death of the last direct Capetian in 1328, the kingdom of France passed to the house of Valois through the Salic law, and Navarre passed to the house of Evreux through female line. | |

| 1376–1469 |

|

|

|

The arms of France Modern: Azure, three fleurs-de-lis or, a simplified version of France Ancient | |

| 1469–1515 |

|

The arms of France Modern. After the creation of the Order of Saint Michael in 1469, its collar was added to the royal arms. | |||

| 1515–1578 |

|

The arms of France Modern. King Francis I changed the open crown traditionally used by his predecessors for a closed one. | |||

| 1578–1589 |

|

The arms of France Modern. After the creation of the Order of the Holy Spirit in 1578, its collar was added to the royal arms. | |||

| 1589–1792 |

|

|

? | The royal arms of the Kingdom of France after the conclusion of the French Wars of Religion. Again the arms of the Kingdom of Navarre impaled with France Moderne, indicating the personal union of the two realms as a result of Henry IV becoming king. | |

| 1790–1792 |

|

|

Alternative Royal Arms of France. | ||

| First Republic | 1791–1804 |

|

|

Putative heraldic emblem of the First French Republic | |

| First Empire | 1804–1814/1815 |

|

|

The arms of the First French Empire of Napoleon I, featuring an eagle, the Crown of Napoleon and inset with "golden bees" as in the tomb of King Childeric I. | |

| Kingdom (Bourbon Restoration) | 1814/1815–1830 |

|

|

After the Bourbon Restoration, the royal House of Bourbon once more assumed the French crown. | |

| Kingdom (July Monarchy) | 1830–1831 |

|

|

During the July Monarchy, the arms of the House of Orléans were used. | |

| 1831–1848 |

|

|

From 1831 onward, the arms of Louis-Philippe were used, depicting the Charter of 1830. (Stars were eventually added to the Mantling; along with addition of Supporters, a decrease of the flags to two, the addition of a helmet, the reversion to the Fleur-de-Lys Crown as one of the two Crowns, the flagpoles having spearheads and at the base were two cannons surmounted by floral branches.) | ||

| Second Empire | 1852–1870 |

|

|

The arms of the Second French Empire of Napoleon III, again featuring an eagle, but now with the Crown of Napoleon III. |

See also

- Armorial of France

- Armorial of presidents of France

- Armorial of the Capetian dynasty

- National symbols of France

- Symbolism in the French Revolution

References

- ^ http://www.hubert-herald.nl/FranFrance.htm

- ^ https://www.max-gueguen.com/reception-demmanuel-macron-a-lhotel-de-ville-de-paris/

- ^ https://www.max-gueguen.com/reception-demmanuel-macron-a-lhotel-de-ville-de-paris/

- ^ "Les symboles de la République française". Site de la présidence de la République.

- ^ "Liberty, Égalité, Fraternité". Embassy of France in the US. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ Ozouf, Mona (1997), "Liberté, égalité, fraternité stands for peace country and war", in Nora, Pierre (ed.), Lieux de Mémoire [Places of memory] (in French), vol. tome III, Quarto Gallimard, pp. 4353–89 (abridged translation, Realms of Memory, Columbia University Press, 1996–98).

- ^ a b Censer and Hunt, "How to Read Images" CD-ROM

- ^ Les Grands Palais de France : Fontainebleau, I re Série, Styles Louis XV, Louis XVI, Empire, Labrairie Centrale D'Art Et D'Architecture, Ancienne Maison Morel, Ch. Eggimann, Succ, 106, Boulevard Saint Germain, Paris, 1910

- ^ Les Grands Palais de France : Fontainebleau , II me Série, Les Appartments D'Anne D'Autriche, De François I er, Et D'Elenonre La Chapelle, Labrairie Centrale D'Art Et D'Architecture, Ancienne Maison Morel, Ch. Eggimann, Succ, 106, Boulevard Saint Germain, Paris, 1912

- ^ a b Site of the French Presidency Archived November 4, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Schierz, Kai Uwe (2004). "Von Bonifatius bis Beuys, oder: Vom Umgang mit heiligen Eichen". In Hardy Eidam; Marina Moritz; Gerd-Rainer Riedel; Kai-Uwe Schierz (eds.). Bonifatius: Heidenopfer, Christuskreuz, Eichenkult (in German). Stadtverwaltung Erfurt. pp. 139–45.

- ^ "Trees – Arbor Day Foundation". Arborday.org. Archived from the original on 28 April 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ^ "Oak Trees". arborday.org. Archived from the original on 9 January 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ^ "Oak as a Symbol". Venables Oak. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ^ a b "Political or Symbolic". Extended Definition: oak. Archived from the original on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ^ "Army Regulation 670-1 | Wear of appurtenances | Section 29.12 Page 278". ar670.com. Archived from the original on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 2018-01-19.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

r8was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

r9was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e Baron, Bruce. "Wreath". Dictionary. Mistholme. Retrieved 2019-09-17.

- ^ https://www.unmultimedia.org/s/photo/detail/704/0070477.html

- ^ https://fotw.info/flags/fr).html

- ^ https://www.unmultimedia.org/s/photo/detail/783/0078376.html

- ^ http://www.hubert-herald.nl/FranFrance.htm

- ^ https://bibliotheques-specialisees.paris.fr/ark:/73873/pf0001198956/0066/v0001.simple.selectedTab=otherdocs.hidesidebar

- ^ https://agorha.inha.fr/inhaprod/ark:/54721/00278365

- ^ https://www.123rf.com/photo_44472384_veliky-novgorod-russia-august-17-2015-coat-of-arms-of-france-represented-in-the-hanseatic-fountain-t.html

- ^ https://www.max-gueguen.com/reception-demmanuel-macron-a-lhotel-de-ville-de-paris/

- ^ File:Visites Mitterrand Chirac à l'hôtel de ville de Paris.jpg

External links

- Symbols of France at Flags of the World

- France at Heraldry of the World

- Heraldry of France — Hubert de Vries website

- Les Armes de Strasbourg — Collection du Mobilier national (in French)

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

![Disks in the UNGA hall to be emblazoned with national arms, including the one submitted by France.[20] The disks were removed in 1956.[21][22]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7c/1952_Trygve_Lie_Resigns.jpg/240px-1952_Trygve_Lie_Resigns.jpg)