Vaquita: Difference between revisions

an automated edit summary is too non-responsive — please do better |

Undid revision 947920226 by El C (talk) Hello! I am a member of the Society for Marine Mammalogy, and I'm working on a team of curators on the Education Committee to update and reformat information on all marine mammal Wikipedia pages so that they have a consistent style in addition to peer-reviewed sources. I am happy to discuss the uniform marine mammal outline outside of these summaries. These updates have not been disputed on other pages. |

||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

The '''vaquita''' (''Phocoena sinus'') is a [[species]] of [[porpoise]] [[endemic]] to the [[Gulf of California]]. It is the smallest of all [[Cetacea|cetaceans]]. Today, the species is on the brink of extinction. Recent research estimates the population at less than 19 individuals.<ref name=":3">{{Cite journal|last=Jaramillo-Legorreta|first=Armando M.|last2=Cardenas-Hinojosa|first2=Gustavo|last3=Nieto-Garcia|first3=Edwyna|last4=Rojas-Bracho|first4=Lorenzo|last5=Thomas|first5=Len|last6=Ver Hoef|first6=Jay M.|last7=Moore|first7=Jeffrey|last8=Taylor|first8=Barbara|last9=Barlow|first9=Jay|last10=Tregenza|first10=Nicholas|title=Decline towards extinction of Mexico's vaquita porpoise (Phocoena sinus)|url=https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsos.190598|journal=Royal Society Open Science|volume=6|issue=7|pages=190598|doi=10.1098/rsos.190598|pmc=PMC6689580|pmid=31417757}}</ref> The steep decline in abundance is primarily due to [[bycatch]] in gillnets from the illegal [[totoaba]] fishery.<ref name=":4">{{Cite journal|last=Rojas-Bracho|first=Lorenzo|last2=Reeves|first2=Randall R.|date=2013-07-03|title=Vaquitas and gillnets: Mexico’s ultimate cetacean conservation challenge|url=https://www.int-res.com/abstracts/esr/v21/n1/p77-87/|journal=Endangered Species Research|language=en|volume=21|issue=1|pages=77–87|doi=10.3354/esr00501|issn=1863-5407}}</ref><ref name=":2">{{Cite web|url=https://www.iucnredlist.org/en|title=IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Vaquita|last=Barbara Taylor (Protected Resources Division|first=Southwest Fisheries Science Center|last2=Rojas-Bracho|first2=Lorenzo|date=2017-07-20|website=IUCN Red List of Threatened Species|access-date=2020-03-29}}</ref> |

|||

The '''vaquita''' ({{IPA-es|baˈkita|lang}}; ''Phocoena sinus'') is a [[species]] of [[porpoise]] [[endemic]] to the northern part of the [[Gulf of California]] that is on the brink of [[extinction]]. Based on beached skulls found in 1950 and 1951, the scientific description of the species was published in 1958.<ref name = "NOAAfacts">{{cite web|url=https://swfsc.noaa.gov/uploadedFiles/VaquitaFactSheet.Version3a.pdf|title=Vaquita Fact Sheet|last=|first=|date=|website=NOAA Fisheries Service Southwest Fisheries Science Center|access-date=June 30, 2018}}</ref> The word ''vaquita'' is Spanish for "little cow". Other names include '''cochito''' (Spanish for "little pig"), '''desert porpoise''', '''vaquita porpoise''', '''Gulf of California harbor porpoise''', '''Gulf of California porpoise''', and '''gulf porpoise'''. Since the [[baiji]] (Yangtze River dolphin, ''Lipotes vexillifer'') is thought to have gone extinct in 2006,<ref name="First human-caused extinction">{{cite journal |last1=Turvey |first1=S. T. |last2=Brandon |first2=J. R. |last3=Richlen |first3=M. |last4=Pusser |first4=L. T. |last5=Zhang |first5=X. |last6=Wei |first6=Z. |last7=Wang |first7=K. |last8=Stewart |first8=B. S. |last9=Reeves |first9=R. R. |last10=Zhao |first10=X. |last11=Barrett |first11=L. A. |last12=Akamatsu |first12=T. |last13=Barlow |first13=J. |last14=Taylor |first14=B. L. |last15=Pitman |first15=R. L. |last16=Wang |first16=D. |title=First human-caused extinction of a cetacean species? |journal=Biology Letters |volume=3 |issue=5 |date=22 October 2007 |pages=537–540 |doi=10.1098/rsbl.2007.0292 |pmid=17686754 |pmc=2391192}}</ref> the vaquita has taken on the title of the most endangered [[cetacea]]n in the world.<ref name="Jaramillo-Legorreta2007">{{cite journal |last1=Jaramillo-Legorreta |first1=A. |last2=Rojas-Bracho |first2=L. |last3=Brownell |first3=R. L. |last4=Read |first4=A. J. |last5=Reeves |first5=R. R. |last6=Ralls |first6=K. |last7=Taylor |first7=B. L. |date=15 November 2007 |title=Saving the vaquita: immediate action, not more data |journal=[[Conservation Biology (journal)|Conservation Biology]] |volume=21 |issue=6 |doi=10.1111/j.1523-1739.2007.00825.x |pmid=18173491 |pages=1653–1655|url=https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdeptcommercepub/81 }}</ref> It has been listed as [[critically endangered]] since 1996.<ref name=IUCN /> The population was estimated at 600 in 1997,<ref name=IUCN /> below 100 in 2014,<ref name="cirva2014">{{cite web |last=Johnson |first=Chris |date=3 August 2014 |title=Report: Vaquita population declines to less than 100 |work=Vaquita: Last Chance for the Desert Porpoise |publisher=earthOcean |url=http://vaquita.tv/blog/2014/08/03/report-vaquita-population-declines-to-less-than-100/ |accessdate=11 August 2014 |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20140812213824/http://vaquita.tv/blog/2014/08/03/report-vaquita-population-declines-to-less-than-100/ |archivedate=12 August 2014}}</ref><ref name="CIRVA-V">{{cite conference |title=Report of the Fifth Meeting of the Comité Internacional para la Recuperación de la Vaquita |publisher = Comité Internacional para la Recuperación de la Vaquita (CIRVA) | date = 3 August 2014 |location=Ensenada, Baja California |url=http://vaquita.tv/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Report-of-the-Fifth-Meeting-of-CIRVA.pdf |format=PDF |accessdate=12 August 2014 |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20140812205522/http://vaquita.tv/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Report-of-the-Fifth-Meeting-of-CIRVA.pdf |archivedate=12 August 2014}}</ref> approximately 60 in 2015,<ref name="may2016" /> around 30 in November 2016,<ref name = "Braulik2017" /><ref name = "CIRVA-8">{{cite web |title=Eighth Meeting of the Comité Internacional para la Recuperación de la Vaquita (CIRVA-8) Southwest Fisheries Science Center |date=1 February 2017 |website=[[IUCN]] |publisher=International Committee for Recovery of the Vaquita |url=http://www.iucn-csg.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/CIRVA-8-Report-Final.pdf |access-date=2017-02-03}}</ref> and only 12-15 in March 2018,<ref name = "Monga2018.03">{{cite web|url=https://news.mongabay.com/2018/03/only-12-vaquita-porpoises-remain-watchdog-groups-report/|title=Only 12 vaquita porpoises remain, watchdog group reports|website=news.mongabay.com|publisher= [[Mongabay]]|language=en-US|access-date=2018-03-09|date=2018-03-08}}</ref> leading to the conclusion that the species will soon be extinct unless drastic action is taken.<ref name = "McGrath2017-05" /> An estimate released in March 2019, based on acoustic data gathered in the summer of 2018, is that a maximum of 22 and a minimum of 6 vaquita porpoises remain, with the [[International Union for Conservation of Nature]] (IUCN) supporting roughly about 10 individuals.<ref name = "MND2019.03.07">{{cite web |url= https://mexiconewsdaily.com/news/count-reveals-just-22-vaquita-remain/| title= Just 22 vaquita porpoises remain and illegal gillnets could soon wipe them out|date= 2019-03-07|website= Mexico News Daily|access-date= 2019-03-14|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20190314202504/https://mexiconewsdaily.com/news/count-reveals-just-22-vaquita-remain/|archive-date= 2019-03-14}}</ref><ref name=":4">{{cite news|url=http://time.com/5552189/sea-shepherd-vaquita-porpoise-endangered-mexico/|title=One of About 10 Endangered Vaquitas Found Dead in Mexico|website=Time|language=en|access-date=2019-03-17}}</ref><ref name = "ME2019-03-16">{{cite web |url= https://www.maritime-executive.com/article/report-only-ten-vaquita-left| title= Report: Only Ten Vaquita Left|date= 2019-03-16|website= The Maritime Executive|access-date= 2019-03-18|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20190318035823/https://www.maritime-executive.com/article/report-only-ten-vaquita-left|archive-date= 2019-03-18}}</ref> A further estimate released in July 2019 concluded that the population size in autumn 2018 was about 9.<ref name="Jaramillo-Legorreta2019">{{cite journal|last1= Jaramillo-Legorreta|first1=A. M.|last2= Cardenas-Hinojosa|first2= G.|last3= Nieto-Garcia|first3= E.|last4= Rojas-Bracho|first4= L.|last5= Thomas|first5= L.|last6=Ver Hoef|first6=J. M.|last7= Moore|first7= J.|last8= Taylor|first8= B.|last9= Barlow|first9= J.|last10= Tregenza|first10= N.|title= Decline towards extinction of Mexico's vaquita porpoise (''Phocoena sinus'')|journal= Royal Society Open Science|volume= 6|issue= 7|year= 2019|pages= 190598|doi= 10.1098/rsos.190598}}</ref> |

|||

The population decrease is largely attributed to [[bycatch]] from the illegal [[Gillnetting|gillnet]] fishery for the [[totoaba]], a similarly sized endemic [[drum (fish)|drum]] that is also critically endangered.<ref name="Braulik2017">{{cite web |last=Braulik |first=G. |date=2017-02-02 |title=Jan 2017 update on the decline of the Vaquita |website=IUCN SSC – Cetacean Specialist Group |publisher=[[IUCN]] |url=http://www.iucn-csg.org/index.php/2017/02/02/2361/ |access-date=2017-02-02}}</ref><ref name="Morell2017">{{cite journal |last=Morell |first=V. |date=2017-02-01 |title=World's most endangered marine mammal down to 30 individuals |journal=Science |doi=10.1126/science.aal0692 |url=http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2017/02/world-s-most-endangered-marine-mammal-down-30-individuals}}</ref><ref name="NPR2016">{{cite web |last=Joyce |first=C. |date=2016-02-09 |title=Chinese Taste For Fish Bladder Threatens Rare Porpoise In Mexico |website=[[National Public Radio]] |url=https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2016/02/09/466185043/chinese-taste-for-fish-bladder-threatens-tiny-porpoise-in-mexico |access-date=2017-02-06}}</ref> The population decline has occurred despite an investment of tens of millions of dollars by the Mexican government in efforts to eliminate the bycatch.<ref name = "CIRVA-8" /> A partial gillnet ban was put in place for two years in May 2015; its scheduled expiration at the end of May 2017 spurred a campaign to have it extended and strengthened.<ref name = "McGrath2017-05" /> On 7 June 2017, an agreement was announced by Mexican president [[Enrique Peña Nieto]] to make the gillnet ban permanent and strengthen enforcement. As well as the Mexican government and various environmental organizations, this effort will now also involve the foundations of Mexican businessman [[Carlos Slim]] and American actor and environmental activist [[Leonardo DiCaprio]].<ref name = "S.D.Union-Tribune2017">{{cite news | last = Dibble | first = S. | title = Mexican billionaire and actor Leonardo DiCaprio join effort to save vaquita porpoise | newspaper = [[San Diego Union-Tribune]] | date = 2017-06-07 | access-date = 2017-06-09 | url = http://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/news/border-baja-california/sd-me-vaquita-plan-20170607-story.html}}</ref> However, the July 2019 report indicated that the gillnet ban had had no effect on the ongoing rate of decline of about 50% per year.<ref name="Jaramillo-Legorreta2019" /> |

|||

A protective housing/captive breeding program, unprecedented for a marine mammal, has been developed and is undergoing feasibility testing, being now viewed as necessary to rescue the species.<ref name="Braulik2017" /><ref name="CIRVA-8" /><ref name="Morell2017" /><ref name="Goldfarb2016a">{{cite journal |last1=Goldfarb |first1=B. |date=2016-07-29 |title=Scientists mull a risky strategy to save world's most endangered porpoise |journal=Science |doi=10.1126/science.aag0706}}</ref><ref name = "vaquitacpr2017-02">{{cite web | url = http://www.nmmf.org/vaquitacpr.html | title = The vaquita porpoise is on the verge of extinction. Please help us save them. | date = February 2017 | website = [[National Marine Mammal Foundation]] | publisher = Consortium for Vaquita Conservation, Protection and Recovery | access-date = 2017-02-05}}</ref> However, the sea pen housing needed to implement this strategy is not expected to be available until October 2017,<ref name = "CIRVA-8" /><ref name="Morell2017" /> which is feared may be too late. Additionally, the ability of the vaquita to survive and reproduce while confined to a sanctuary is uncertain.<ref name = "Greenpeace2017-02-02">{{cite web | url = http://www.ecowatch.com/vaquita-on-brink-of-extinction-2233479187.html | title = Vaquita on Brink of Extinction, Only 30 Remain in the Wild | date = 2017-02-02 | last = [[Greenpeace]] | website = EcoWatc | access-date = 2017-02-04}}</ref> The Mexican government approved the plan on 3 April 2017, with commencement projected to begin in October 2017.<ref name="Nicholls2017">{{cite journal|last1=Nicholls|first1=H.|title=Last-ditch attempt to save world's most endangered porpoise gets go-ahead|journal=Nature|date=2017-04-07|doi=10.1038/nature.2017.21791}}</ref> |

|||

In November 2017, the attempt to capture wild vaquitas for captive breeding and safekeeping was suspended following the death of a female vaquita. The adult female died within hours of being captured.<ref name="Gotfredson 2017">{{cite news |last=Gotfredson |first=David |date=2017-11-08 |title=Vaquita porpoise capture operations end on Sea of Cortez |url=http://www.cbs8.com/story/36795675/vaquita-porpoise-capture-operations-end-on-sea-of-cortez |work=CBS 8 |location=San Diego, CA |access-date=2017-11-08 }}</ref><ref name="Pennisi2017">{{cite journal|last1= Pennisi|first1= E.|title= After failed rescue effort, rare porpoise in extreme peril|journal= Science|volume= 358|issue= 6365|page= 851|date= 17 November 2017|doi= 10.1126/science.358.6365.851 |pmid= 29146787}}</ref> In December 2017, Mexico, the United States and China agreed to take further steps to prevent trade in totoaba bladders.<ref name = "CITES_2017.12">{{cite web | url = https://news.mongabay.com/2017/12/cites-rejects-madagascars-bid-to-sell-rosewood-and-ebony-stockpiles/ | title = CITES rejects Madagascar's bid to sell rosewood and ebony stockpiles | page= (see end of article) | last = Carver | first = E. | date = 2017-12-12 | website = news.Mongabay.com | publisher = [[Mongabay]].org | access-date = 2017-12-14}}</ref> Despite its extremely low population, reports indicate the small number of surviving vaquita are still relatively healthy and able to breed.<ref name=":4" /><ref name = "Katz2019">{{cite web |url= https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/there-are-most-19-vaquitas-left-wild-180972791/|title= There Are ‘At Most’ 19 Vaquitas Left in the Wild|last= Katz|first= B.|date=1 August 2019 |website= SmithsonianMag.com|publisher= [[Smithsonian]]|access-date= 2019-08-06}}</ref><ref name=":5" /> However, the intensifying [[poaching]] and the extremely low population make it likely that the species will go extinct unless drastic measures are taken.<ref name = "Monga2018.03" /> If the species does go extinct, it will likely be the first cetacean to do so since the [[baiji]]. |

|||

==Description== |

==Description== |

||

[[File:Vaquita2 Olson NOAA.jpg|thumb|Characteristic dark eye rings]] |

|||

Vaquitas are the smallest and most endangered species of the infraorder Cetacea and are endemic to the northern end of the Gulf of California. The vaquita is somewhat stocky and has a characteristic porpoise shape. The species is distinguishable by the dark rings surrounding their eyes, patches on their lips, and a line that extends from their dorsal fins to their mouths. Their backs are a dark grey that fades to white undersides. As vaquitas mature, the shades of grey lighten.<ref name=barlow>{{cite web |

|||

Vaquitas are the smallest species of cetacean, and can be easily distinguished from any other species in their range. They have a small body with an unusually tall, triangular dorsal fin, a rounded head, and no distinguished beak. Their coloration is mostly grey with a darker back and a white ventral field. Prominent black patches surround their lips and eyes.<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Brownell|first=Robert L.|last2=Findley|first2=Lloyd T.|last3=Vidal|first3=Omar|last4=Robles|first4=Alejandro|last5=Manzanilla|first5=N. Silvia|date=1987|title=External Morphology and Pigmentation of the Vaquita, Phocoena Sinus (cetacea: Mammalia)|url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1748-7692.1987.tb00149.x|journal=Marine Mammal Science|language=en|volume=3|issue=1|pages=22–30|doi=10.1111/j.1748-7692.1987.tb00149.x|issn=1748-7692}}</ref> [[Sexual dimorphism]] is apparent in body size, with mature females being longer than males and having larger heads and wider flippers.<ref name=":0" /><ref name=":1">{{Cite journal|last=Torre|first=Jorge|last2=Vidal|first2=Omar|last3=Brownell|first3=Robert L.|date=2014-10|title=Sexual dimorphism and developmental patterns in the external morphology of the vaquita, Phocoena sinus|url=http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/mms.12106|journal=Marine Mammal Science|language=en|volume=30|issue=4|pages=1285–1296|doi=10.1111/mms.12106}}</ref> Females reach a maximum size of about 150 cm, while males reach about 140 cm.<ref name=":0" /> Dorsal fin height is greater in males than in females.<ref name=":1" /> |

|||

| last = Barlow | first = J. | authorlink = |

|||

| title = Vaquita (''Phocoena sinus'') |

|||

| work = EDGE of Existence programme |

|||

| publisher = [[Zoological Society of London]] | date = 2014 |

|||

| url = http://www.edgeofexistence.org/mammals/species_info.php?id=78 |

|||

| accessdate = 20 January 2014}}</ref> Female vaquitas tend to grow larger than males.<ref name= barlow /> On average, females mature to a length of {{convert|1.406|m|ft|abbr=on|adj=ri2|sigfig=2}}, compared to {{convert|1.349|m|ft|abbr=on|adj=ri2|sigfig=2}} for males. The lifespan, pattern of growth, seasonal reproduction, and testes size of the vaquita are all similar to that of the [[harbour porpoise]].<ref name="Hohn1996">{{Cite journal | last1 = Hohn | first1 = A. A. | last2 = Read | first2 = A. J. | last3 = Fernandez | first3 = S. | last4 = Vidal | first4 = O. | last5 = Findley | first5 = L. T. | title = Life history of the vaquita, ''Phocoena sinus'' (Phocoenidae, Cetacea) | doi = 10.1111/j.1469-7998.1996.tb05450.x | journal = [[Journal of Zoology]]| volume = 239 | issue = 2 | pages = 235–251| date = June 1996 | pmid = | pmc = }}</ref> The [[flipper (anatomy)|flippers]] are proportionately larger than those of other porpoises, and the fin is taller and more [[wiktionary:falcate|falcated]]. The skull is smaller and the [[rostrum (anatomy)|rostrum]] is shorter and broader than in other members of the genus. |

|||

==Geographic range and distribution== |

|||

==Taxonomy== |

|||

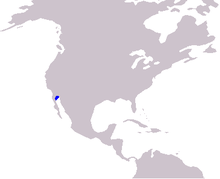

Vaquita habitat is restricted to a small portion of the upper Gulf of California (also called the [[Sea of Cortez]]), making this the smallest range of any marine mammal species. They live in shallow, turbid waters of less than 50 m depth (150 ft).<ref name=":2" /> |

|||

The porpoise genus ''[[Phocoena]]'' comprises four species, all of which inhabit coastal waters, two each in the northern and southern hemispheres. Vaquitas are believed on the basis of morphological and genetic evidence to be most closely related to [[Burmeister's porpoise]] (''P. spinipinnis'') of South America. Their ancestors are thought to have crossed the equator during a cooler period of the [[Pleistocene]].<ref name = "NOAAfacts" /> |

|||

==Behavior== |

==Behavior== |

||

===Foraging=== |

|||

Vaquitas use high-pitched sounds to communicate with one another and for [[Animal echolocation#Toothed whales|echolocation]] to navigate through their habitats. They generally feed and swim at a leisurely pace. Vaquitas avoid boats and are very evasive. They rise to breathe with a slow, forward motion and then disappear quickly. This lack of activity at the surface makes them difficult to observe.<ref name = NOAA_Vaquita/> Vaquitas are usually alone unless they are accompanied by a calf,<ref name=Vaquita2>{{cite web|title=About the Vaquita| url= http://www.savethevaquita.org/|date=January 2014|publisher= Save The Vaquita Project|accessdate=20 January 2014}}</ref> meaning they are less social than other porpoise species. They may also be more competitive during mating season.<ref name=Vaquita3>{{cite web|title= Vaquitas, ''Phocoena sinus''|website= MarineBio.org|url= http://marinebio.org/species.asp?id=361|publisher= MarineBio Conservation Society|date= 14 January 2013|accessdate= 20 January 2014|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20180913074114/http://marinebio.org/species.asp?id=361|archive-date= 13 September 2018|url-status= dead}}</ref> They are the only species belonging to the porpoise family that live in warm waters.<ref name=Vaquita4>{{cite web|title=Basic Facts About Vaquitas|url=http://www.defenders.org/vaquita/basic-facts|publisher= Defenders of Wildlife|work = Wild Places and Wildlife|date= 2013|accessdate=20 January 2014}}</ref> Vaquitas are non-selective predators.<ref name=Vaquita6>{{cite web|last=Rojas-Bracho|first=L.|title=Vaquita (''P. sinus'')|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20141107192422/http://www.marinemammalscience.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=501&Itemid=315|archive-date= 2014-11-07|url= http://www.marinemammalscience.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=501&Itemid=315| publisher= [[Society for Marine Mammalogy]]|work= Species fact Sheets|accessdate=20 January 2014}}</ref> |

|||

Vaquitas are generalists, foraging on a variety of [[Demersal fish|demersal]] fish species, [[Crustacean|crustaceans]], and [[Squid|squids]], though benthic fish such as grunts and [[Sciaenidae|croakers]] are mostly fed on.<ref name=":2" /> |

|||

=== |

===Social=== |

||

[[File:Vaquita6 Olson NOAA.jpg|thumb|A pair of vaquitas]] |

|||

Like other ''[[Phocoena]]'', vaquitas are usually seen singly. If they are seen together, it is usually in small groups of two or three individuals.<ref name=barlow /> Less often, groups around ten have been observed, with the most ever seen at once being 40 individuals.{{citation needed|date= March 2016}} |

|||

Vaquitas are generally seen singly or in pairs, often with a calf, but have been observed in small groups of up to 10 individuals.<ref name=":2" /> |

|||

Little is known about the life history of this species. Life expectancy is estimated at about 20 years and age of sexual maturity is somewhere between 3 and 6 years of age.<ref name=":5">{{Cite journal|last=Hohn|first=A. A.|last2=Read|first2=A. J.|last3=Fernandez|first3=S.|last4=Vidal|first4=O.|last5=Findley|first5=L. T.|date=1996|title=Life history of the vaquita, Phocoena sinus (Phocoenidae, Cetacea)|url=https://zslpublications.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1996.tb05450.x|journal=Journal of Zoology|language=en|volume=239|issue=2|pages=235–251|doi=10.1111/j.1469-7998.1996.tb05450.x|issn=1469-7998}}</ref> While an initial analysis of stranded vaquitas estimated a two-year calving interval, recent sightings data suggest that vaquitas can reproduce annually.<ref name=":5" /><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Taylor|first=Barbara L.|last2=Wells|first2=Randall S.|last3=Olson|first3=Paula A.|last4=Brownell|first4=Robert L.|last5=Gulland|first5=Frances M. D.|last6=Read|first6=Andrew J.|last7=Valverde‐Esparza|first7=Francisco J.|last8=Ortiz‐García|first8=Oscar H.|last9=Ruiz‐Sabio|first9=Diego|last10=Jaramillo‐Legorreta|first10=Armando M.|last11=Nieto‐Garcia|first11=Edwyna|date=2019|title=Likely annual calving in the vaquita, Phocoena sinus: A new hope?|url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/mms.12595|journal=Marine Mammal Science|language=en|volume=35|issue=4|pages=1603–1612|doi=10.1111/mms.12595|issn=1748-7692}}</ref> It is thought that vaquitas have a polygynous mating system in which males compete for females. This competition is evidenced by the presence of sexual dimorphism (females are larger than males), small group sizes, and large testes (accounting for nearly 3% of body mass).<ref name=":5" /> |

|||

===Diet=== |

|||

Vaquitas tend to forage near lagoons.<ref name= barlow /> All of the 17 fish species found in vaquita stomachs can be classified as [[demersal]] and or [[benthic]] species inhabiting relatively shallow water in the upper [[Gulf of California]]. Vaquitas appear to be rather non-selective feeders on crustaceans, small fish, octopuses and [[squid]] in this area.<ref name=IUCN/><ref name = NOAA_Vaquita /> Some of the most common prey are [[teleost]]s (fish with bony skeletons) such as [[Haemulidae|grunt]]s, [[Sciaenidae|croaker]]s, and [[sea trout]].<ref name="Rice">{{cite web | last = Rice | first = Danielle | title = About the Vaquita: An Endangered Animal | work = Vaquita: An Endangered Species | date = 2 May 2011 | url = http://www.cgdsite.com/ricedanielle/cc_site/about.html | accessdate = 20 January 2014 | archiveurl = https://web.archive.org/web/20131029192355/http://www.cgdsite.com/ricedanielle/cc_site/about.html | archivedate = 29 October 2013}}</ref> Like other [[cetacea]]ns, vaquitas may use echolocation to locate prey,<ref name = "Silber1991">{{cite journal | last = Silber | first = G. K. | title = Acoustic signals of the vaquita (''Phocoena sinus'') | journal = Aquatic Mammals | volume = 17 | issue = 3 | pages = 130–133 | date = 1991 | url = http://www.aquaticmammalsjournal.org/share/AquaticMammalsIssueArchives/1991/Aquatic_Mammals_17_3/Silber.pdf | access-date = 2017-02-06}}</ref> particularly as their habitat is often turbid.<ref name=IUCN/> |

|||

==Taxonomy== |

|||

===Life cycle and reproduction=== |

|||

The genus ''Phocoena'' comprises four species of porpoise, most of which inhabit coastal waters (the [[spectacled porpoise]] is more oceanic). The vaquita was first described as a species in 1958 after studying the morphology of skull specimens found on the beach.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Norris|first=Kenneth S.|last2=McFarland|first2=William N.|date=1958-02-20|title=A New Harbor Porpoise of the Genus Phocoena from the Gulf of California|url=https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article/39/1/22/836545|journal=Journal of Mammalogy|language=en|volume=39|issue=1|pages=22–39|doi=10.2307/1376606|issn=0022-2372}}</ref> It was not until nearly thirty years later, in 1985, that fresh specimens allowed scientists to describe their external appearance fully.<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

[[File:Vaquita6 Olson NOAA.jpg|thumb|Vaquita pair]] |

|||

Little is known about the life cycle of vaquitas. Age at sexual maturity, longevity, reproductive cycle and population dynamics estimates have been made, but further research is needed. Most of these estimates come from vaquitas that have been stranded or caught in nets. Some are based on other porpoise species similar to vaquitas. |

|||

Vaquitas are most closely related to [[Burmeister's porpoise|Burmeister’s porpoise]] (''Phocoena spinipinnis'') and less so to the spectacled porpoise (''Phocoena dioptrica''), two species limited to the Southern Hemisphere. Their ancestors are thought to have moved north across the equator more than 2.5 million years ago during a period of cooling in the [[Pleistocene]].<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

Vaquitas are estimated to live about 20 years in ideal conditions.<ref name="Rojas1">{{Cite journal|last1=Rojas-Bracho|first1=L.|last2=Reeves|first2=R. R.|last3=Jaramillo-Legorreta|first3=A.|date=13 November 2006|title=Conservation of the vaquita ''Phocoena sinus''|journal=[[Mammal Review]]|volume=36|issue=3|pages=179–216|doi=10.1111/j.1365-2907.2006.00088.x|pmc=|pmid=}}</ref><ref name="Avila-Forcada2011">{{Cite journal | last1 = Avila-Forcada | first1 = S. | last2 = Martínez-Cruz | first2 = A. N. L. | last3 = Muñoz-Piña | first3 = C. | doi = 10.1016/j.marpol.2011.10.012 | title = Conservation of vaquita marina in the Northern Gulf of California | journal = Marine Policy | volume = 36 | issue = 3 | pages = 613–622| date = May 2012 | pmid = | pmc = }}</ref> They mature sexually at 1.3 m long, as early as 3 years old, but more likely at 6. Reproduction occurs during late spring or early summer. Their gestation period is between 10 and 11 months. They have seasonal reproduction, and usually have one calf in March. The inter-birth period, or elapsed time between offspring birth, is between 1 and 2 years. The young are then nursed for about 6 to 8 months until they are capable of fending for themselves.<ref name="JeffersonWebber2011">{{cite book|first1= Thomas A. |last1= Jefferson|first2= Marc A. |last2= Webber| first3= Robert L. |last3= Pitman|title=Marine Mammals of the World: A Comprehensive Guide to Their Identification|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_IY2n07t7QYC&pg=PA288|date=29 August 2011|publisher=Academic Press|isbn= 978-0-08-055784-7|pages= 288–289|oclc= 326418543}}</ref> |

|||

==Population status== |

|||

==Distribution and habitat== |

|||

Because the vaquita was only fully described in the late 1980s, historical abundance is unknown.<ref name=":6">{{Cite journal|last=Rojas‐Bracho|first=Lorenzo|last2=Reeves|first2=Randall R.|last3=Jaramillo‐Legorreta|first3=Armando|date=2006|title=Conservation of the vaquita Phocoena sinus|url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-2907.2006.00088.x|journal=Mammal Review|language=en|volume=36|issue=3|pages=179–216|doi=10.1111/j.1365-2907.2006.00088.x|issn=1365-2907}}</ref> The first comprehensive vaquita survey throughout their range took place in 1997 and estimated a population of 567 individuals.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Jaramillo‐Legorreta|first=Armando M.|last2=Rojas‐Bracho|first2=Lorenzo|last3=Gerrodette|first3=Tim|date=1999|title=A New Abundance Estimate for Vaquitas: First Step for Recovery1|url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1748-7692.1999.tb00872.x|journal=Marine Mammal Science|language=en|volume=15|issue=4|pages=957–973|doi=10.1111/j.1748-7692.1999.tb00872.x|issn=1748-7692}}</ref> By 2007 abundance was estimated to have dropped to 150.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Jaramillo-Legorreta|first=Armando|last2=Rojas-Bracho|first2=Lorenzo|last3=Brownell|first3=Robert L.|last4=Read|first4=Andrew J.|last5=Reeves|first5=Randall R.|last6=Ralls|first6=Katherine|last7=Taylor|first7=Barbara L.|date=2007-11-15|title=Saving the Vaquita: Immediate Action, Not More Data|url=http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2007.00825.x|journal=Conservation Biology|language=en|volume=0|issue=0|pages=071117012342001–???|doi=10.1111/j.1523-1739.2007.00825.x|issn=0888-8892}}</ref> Population abundance as of 2018 was estimated at less than 19 individuals.<ref name=":3" /> Given the continued rate of '''bycatch''' and low reproductive output from a small population, it is possible that there are as few as 10 vaquitas alive today.<ref name=":3" /><ref name=":7">{{Cite web|url=http://www.iucn-csg.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/CIRVA-11-Final-Report-6-March.pdf|title=Report of the Eleventh meeting of the |

|||

The habitat of the vaquita is restricted to the northern area of the Gulf of California, or Sea of Cortez.<ref name=gale /> They live in shallow, murky [[lagoon]]s along [[shoreline]]s. They rarely swim deeper than {{convert|30|m|abbr=on|sigfig=1}} and are known to survive in lagoons so shallow that their backs protrude above the surface. The vaquita is most often sighted in water {{convert|11|to|50|m|abbr=on|sigfig=2}} deep, {{convert|11|to|25|km|abbr=on|sigfig=2}} from the coast, over silt and clay bottoms. They tend to choose habitats with [[Turbidity|turbid]] waters, because they have high nutrient content,<ref name=IUCN/> which is important because it attracts the small fish, squid, and crustaceans on which they feed. They are able to withstand the significant temperature fluctuations characteristic of shallow, turbid waters and lagoons. |

|||

Comité Internacional para la |

|||

Recuperación de la Vaquita (CIRVA)|last=|first=|date=|website=|url-status=live|archive-url=|archive-date=|access-date=}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.vivavaquita.org/|title=The Vaquita Porpoise: A Conservation Emergency|last=|first=|date=|website=VIVA Vaquita|url-status=live|archive-url=|archive-date=|access-date=}}</ref> |

|||

== |

==Threats== |

||

===Fisheries bycatch=== |

|||

The vaquita is considered the most endangered of 129 extant marine mammal species.<ref name="Pompa2011">{{Cite journal | last1 = Pompa | first1 = S. | last2 = Ehrlich | first2 = P. R. | last3 = Ceballos | first3 = G. | doi = 10.1073/pnas.1101525108 | title = Global distribution and conservation of marine mammals | journal = [[Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences]]| volume = 108 | issue = 33 | pages = 13600–13605| date = 16 August 2011| pmid = 21808012| pmc = 3158205}}</ref> It has been classified as one of the top 100 [[EDGE species|evolutionary distinct and globally endangered]] (EDGE) mammals in the world.<ref name="barlow"/> The vaquita is an evolutionarily distinct animal and has no close relatives. These animals represent more, proportionally, of the tree of life than other species, meaning they are top priority for conservation campaigns. The [[EDGE of Existence Programme]] is a conservation effort that attempts to help conserve endangered animals that represent large portions of their evolutionary trees. The U.S. government has listed the vaquita as endangered under the [[Endangered Species Act]]. It is also listed by the [[International Union for Conservation of Nature|IUCN]] and the [[CITES]] in the category at most critical risk of extinction. |

|||

[[File:Vaquita3 Olson NOAA.jpg|thumb|A vaquita swims in the foreground with fishing boats in the distance]]The drastic decline in vaquita abundance is the result of fisheries bycatch in commercial and illegal [[Gillnetting|gillnets]], including fisheries targeting the now-[[Endangered species|endangered]] totoaba, shrimp, and other available fish species.<ref name=":4" /><ref name=":6" /> In spite of government regulations, including a partial gillnet ban in 2015 and establishment of a permanent gillnet exclusion zone in 2017, [[Illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing|illegal fishing]] remains prevalent in vaquita habitat, and as a result the population has continued to decline.<ref name=":3" /> |

|||

=== |

=== Other threats === |

||

Given their proximity to the coast, vaquitas are exposed to habitat alteration and [[pollution]] from runoff. There is no evidence, however, that these threats have made any significant contribution to their decline. Bycatch is the single biggest threat to the survival of the few remaining vaquita.<ref name=":7" /> |

|||

[[File:Vaquita3 Olson NOAA.jpg|thumb|A vaquita swims in the foreground while fishing boats ply their trade in the distance.]] |

|||

Vaquitas have never been hunted directly, but their population is declining, largely because of animals becoming trapped in illegal [[gillnet]]s intended for capturing the [[totoaba]], a large critically endangered fish of the [[Sciaenidae|drum family]] endemic to the Gulf. A trade in totoaba [[swim bladder]]s has arisen, driven by demand from China (where they are used in soup, being considered a delicacy and also erroneously thought to have medicinal value<ref name="Morell2017" />), which is greatly exacerbating the problem.<ref name="cirva2014" /><ref name = "CIRVA-V" /> |

|||

==Conservation status== |

|||

Estimates placed the vaquita population at 567 in 1997.<ref name=gale>{{cite book|author= Emanoil, M.|title= Encyclopedia of Endangered Species|chapter-url= https://books.google.com/books?id=F6gRAQAAMAAJ&focus=searchwithinvolume&q=vaquita|page= [https://archive.org/details/encyclopediaofen00eman/page/266 266]|date= 1 February 2009|chapter= Vaquita (''Phocoena sinus'')|volume= 1|publisher= Gale Research|isbn= 978-0-8103-8857-4|url-access= registration|url= https://archive.org/details/encyclopediaofen00eman/page/266}}</ref> Estimates in the 2000s ranged between 150<ref name="Carwardine">{{cite book|first= Mark |last= Carwardine|title=Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4s-WQwAACAAJ|date=1995|publisher=Dorling Kindersley|isbn= 978-1-4053-5794-4|oclc= 31010070}}</ref><ref name= Passport>''Aquarium Passport Book'', [http://www.aquariumofpacific.org Aquarium of the Pacific], 2005.</ref> to 300.<ref name=Passport /> |

|||

The vaquita is listed as [[Critically endangered|Critically Endangered]] on the [[IUCN Red List]].<ref name=":2" /> Today, this is the most endangered marine mammal in the world.<ref name=":3" /><ref name=":2" /> |

|||

The species is also protected under the US [[Endangered Species Act of 1973|Endangered Species Act]], the Mexican Official Standard NOM-059 ([[Norma Oficial Mexicana]]) , and Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora ([[CITES]]). |

|||

With their population dropping as low as 85 individuals in 2014,<ref>{{cite web| url=http://www.vivavaquita.org/|title=¡Viva Vaquita!|work=¡Viva}}</ref> [[inbreeding depression]] has probably begun to affect the [[Fitness (biology)|fitness]] of the species, potentially contributing to the population's further decline.<ref name="Taylor2006">{{Cite journal | last1 = Taylor | first1 = B. L. | last2 = Rojas-Bracho | first2 = L. | doi = 10.1111/j.1748-7692.1999.tb00875.x | title = Examining the risk of inbreeding depression in a naturally rare cetacean, the vaquita (''Phocoena sinus'') | journal = Marine Mammal Science| volume = 15 | issue = 4 | pages = 1004–1028| date = October 1999 | pmid = | pmc = | url = https://zenodo.org/record/1230744 }}</ref> |

|||

===Conservation efforts=== |

|||

In 2014, estimates of the species' abundance dropped below 100 individuals.<ref name="cirva2014" /> An international vaquita recovery team concluded that the population is decreasing at a rate of 18.5% per year, and "the species will soon be extinct unless drastic steps are taken immediately."<ref name = "CIRVA-V" /> Their report recommended that a ban on gillnet fishing be enforced throughout the range of the vaquita, that action be taken to eliminate the illegal fishery for the totoaba, and that with help from the U.S. and China, trade in totoaba swim bladders be halted.<ref name="cirva2014" /><ref name = "CIRVA-V" /> |

|||

The Mexican government, international committees, scientists, and conservation groups have recommended and implemented plans to help reduce the rate of bycatch, enforce gillnet bans, and promote population recovery. |

|||

Mexico launched a program in 2008 called PACE-VAQUITA in an effort to enforce the gillnet ban in the Biosphere Reserve, allow fishermen to swap their gillnets for vaquita-safe fishing gear, and provide economic support to fishermen for surrendering fishing permits and pursuing alternative livelihoods.<ref name=":8">{{Cite web|url=https://iucn-csg.org/vaquita/|title=Vaquita – IUCN – SSC Cetacean Specialist Group|language=en-US|access-date=2020-03-29}}</ref> Despite the progress made with legal fishermen, hundreds of [[Poaching|poachers]] continued to fish in the exclusion zone. |

|||

On 16 April 2015, [[Enrique Peña Nieto]], [[President of Mexico]], announced a program to conserve and protect the vaquita and the similar-sized totoaba, including a two-year ban on gillnet fishing in the area, patrols by the [[Mexican Navy]] and financial support to fishermen impacted by the plan.<ref>{{cite web| url=http://www.eluniversal.com.mx/in-english/2015/us-supports-mexicos-efforts-to-save-the-vaquita-104396.html|title= U.S. supports Mexico's efforts to save the vaquita|date=16 April 2015|work=El Universal}}</ref><ref name = "Malkin2015">{{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/17/world/americas/mexicos-president-rolls-out-plan-to-save-endangered-porpoise.html|title= Mexico's President Rolls Out Plan to Save Endangered Porpoise|first=E.|last= Malkin|date=16 April 2015|work=The New York Times}}</ref> However, some commentators believe the measures fall short of what is needed to ensure the species' survival.<ref>{{cite web| last= Smith| first= Zak| work= nrdc.org| url= http://switchboard.nrdc.org/blogs/zsmith/call_to_ban_mexican_seafood_products.html| date= 16 March 2015| title= The Call to Ban Mexican Seafood Products Gets Louder After Mexico Announces its Plan for Vaquita Extinction| access-date= 17 April 2015| archive-url= https://archive.is/20150417204654/http://switchboard.nrdc.org/blogs/zsmith/call_to_ban_mexican_seafood_products.html| archive-date= 17 April 2015| url-status= dead| df= dmy-all}}</ref> |

|||

With continued illegal totoaba fishing and uncontrolled bycatch of vaquitas, the International Committee for the Recovery of the Vaquita (CIRVA) recommended that some vaquitas be removed from the high-density fishing area and be relocated to protected sea pens. This effort, called [https://www.vaquitacpr.org/rescue-efforts/ VaquitaCPR], captured two vaquitas in 2017: one was later released and the other died shortly after capture after both suffered from shock.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Rojas-Bracho|first=L|last2=Gulland|first2=FMD|last3=Smith|first3=CR|last4=Taylor|first4=B|last5=Wells|first5=RS|last6=Thomas|first6=PO|last7=Bauer|first7=B|last8=Heide-Jørgensen|first8=MP|last9=Teilmann|first9=J|last10=Dietz|first10=R|last11=Balle|first11=JD|date=2019-01-11|title=A field effort to capture critically endangered vaquitas Phocoena sinus for protection from entanglement in illegal gillnets|url=https://doi.org/10.3354/esr00931|journal=Endangered Species Research|language=en|volume=38|pages=11–27|doi=10.3354/esr00931|issn=1863-5407}}</ref> |

|||

In early May 2016, the [[IUCN Species Survival Commission|IUCN SSC]] – Cetacean Specialist Group reported that the vaquita population had dipped to around 60 remaining individuals in 2015. This represents a 92% decline from the 1997 population level. In March 2016 alone, at least three vaquitas drowned after being entangled in gillnets set for totoaba.<ref name="may2016">{{cite news|last1=Sanders|first1=Natalie|title=Stronger protection needed to prevent imminent extinction of Mexican porpoise vaquita, new survey finds|url=http://www.iucn-csg.org/index.php/2016/05/14/stronger-protection-needed-to-prevent-imminent-extinction-of-mexican-porpoise-vaquita-new-survey-finds/|accessdate=16 May 2016|work=www.iucn-csg.org|publisher=[[IUCN Species Survival Commission]]|date=14 May 2016}}</ref> The report concluded that the gillnet ban would need to be extended indefinitely, with more effective enforcement, if the vaquita is to have any chance of long term survival. Otherwise, the species is likely to become extinct within 5 years.<ref name="may2016" /> |

|||

Local and international conservation groups, including Museo de Ballena and [[Sea Shepherd Conservation Society]], are working with the Mexican Navy to detect fishing in the Refuge Area and remove illegal gillnets.<ref name=":8" /> |

|||

By November 2016, according to a report released in February 2017, the population had declined to about 30, and it was judged that capture of some of the remaining vaquitas and conducting a captive breeding program within a secure sanctuary was the only remaining hope for survival.<ref name = "Braulik2017" /><ref name = "CIRVA-8" /> This is despite the fact that porpoises generally fare poorly in captivity.<ref name = "Greenpeace2017-02-02" /> However, the head of the Mexican environmental agency asserted in July 2017 that at least 100 individuals remain.<ref>The Mexico News Daily. 2017. [http://mexiconewsdaily.com/news/more-vaquitas-remain-than-thought-profepa/ More vaquitas remain than thought: Profepa]. Retrieved on July 26, 2017</ref> |

|||

To date, efforts have been unsuccessful in solving the complex [[Socioeconomics|socioeconomic]] and environmental issues that impact vaquita conservation and the greater Gulf of California ecosystem. Necessary action includes habitat protection, resource management, education, fisheries enforcement, alternative livelihoods for fishermen, and raising awareness of the vaquita and associated issues.<ref name=":2" /> |

|||

By March 2018, an interview with the watchdog group Elephant Action League revealed that based on recordings of vaquita calls from multiple sources, there were likely only a dozen remaining vaquita in the region. According to the interview, despite the recent efforts to curb poaching, dozens of poachers have still been seen fishing every night. It remains unlikely that the population will survive the next totoaba fishing season, which began around the same time the interview was released.<ref name = "Monga2018.03" /> In response to the endangerment of the vaquita, a federal judge ordered President [[Donald Trump]] to ban the import of gillnet-harvested seafood from the Gulf of California into the [[United States]] later in the year.<ref name=":2">{{Cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/17/science/vaquitas-endangered-porpoise.html|title=Scientists Catch Rare Glimpses of the Endangered Vaquita|last=Malkin|first=Elisabeth|date=2018-10-17|work=The New York Times |

|||

|access-date=2018-10-19|language=en}}</ref> |

|||

A survey later in 2018 sighted 6-7 vaquita, possibly about half of the species' current population. However, renewing hopes for the species was the sighting of "Ana", a female vaquita previously seen with a newborn calf in 2017. "Ana" was also seen with another calf in the 2018 survey, indicating that the small population still has the ability to sustain itself, and that the reproduction rate of the species may be annual rather than biennial as thought before. However, acoustic studies have indicated that only about 15 individuals still exist in a very small rectangular area about {{convert|12|by|25|mi|km|disp=flip|abbr=on}}; a reduction of about 86% of the species' historic range.<ref name=":2" /><ref name=":3">{{cite news|url=https://www.apnews.com/c444c22a4cb9490590f205fe6601e918|title=Experts urge gulf refuge for endangered vaquita porpoise|date=2018-10-17|agency=Associated Press|access-date=2018-10-19}}</ref> |

|||

A 2019 survey found a badly-decomposed vaquita corpse, likely one of the handful remaining, caught in a gillnet, indicating that the species is still at risk from gillnets even despite its very small population.<ref name=":4" /> On July 2019 a Royal Society Research article estimated fewer than 19 vaquitas remained as of summer 2018 and that from March 2016 to March 2019, 10 dead vaquitas killed in [[Gillnetting|gillnets]] were found.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Jaramillo-Legorreta|first=Armando M.|last2=Cardenas-Hinojosa|first2=Gustavo|last3=Nieto-Garcia|first3=Edwyna|last4=Rojas-Bracho|first4=Lorenzo|last5=Thomas|first5=Len|last6=Ver Hoef|first6=Jay M.|last7=Moore|first7=Jeffrey|last8=Taylor|first8=Barbara|last9=Barlow|first9=Jay|last10=Tregenza|first10=Nicholas|title=Decline towards extinction of Mexico's vaquita porpoise (Phocoena sinus)|url=https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsos.190598|journal=Royal Society Open Science|volume=6|issue=7|pages=190598|doi=10.1098/rsos.190598|pmc=6689580|pmid=31417757}}</ref> In late 2019, a survey found at least 6 distinct individuals, among them 3 mother-and-calf pairs, supporting the idea that the population may still be viable.<ref name=":5">{{Cite web|url=https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/news/environment/story/2019-11-22/scientists-spot-critically-endangered-vaquita-porpoises-with-babies|title=Scientists spot critically endangered vaquita porpoises with babies|date=2019-11-23|website=San Diego Union-Tribune|language=en-US|access-date=2019-11-24}}</ref> |

|||

=== Primary threats === |

|||

[[File:Vaquita2 Olson NOAA.jpg|thumb|Vaquitas have dark eye rings.]] |

|||

Accidental drowning in gillnets set by fishermen meant for catching totoaba is the primary cause of anthropogenic, incidental mortality for the vaquita. Three fishing villages in the northern Gulf of California are primarily involved in the totoaba fishery and, as a result, most directly involved in threats to the vaquita. [[San Felipe, Baja California|San Felipe]], in Baja California, and [[San Luis Río Colorado Municipality#Populated places|Golfo de Santa Clara]] and [[Puerto Peñasco]], in Sonora, have a total population of approximately 61,000. Up to 80% of the economy in these towns is associated with the [[fishing industry]]. A total of 1771 vessels make up the artisanal fleet that have permits to fish with nets, with the total size of the commercial fishery unknown due to the extent of the black market for totoaba.<ref>''Action Program For the Conservation of the Species''. United Mexican States Federal Government, 2008, pp. 1–76, ''Action Program For the Conservation of the Species''.</ref> Around 3,000 individuals are involved in the totoaba industry overall.<ref name=":0">Pitman, Robert L.; Rojas-Bracho, Lorenzo (July–August 2007). [http://www.naturalhistorymag.com/htmlsite/master.html?http://www.naturalhistorymag.com/htmlsite/0707/0707_feature2.html "How Now, Little Cow?"]. ''Natural History''.</ref> The total economic impact of the industry for the region is estimated to be approximately US$5.4 million annually, or $78.5 million Pesos. Socioeconomic surveys of the northern Gulf have suggested that approximately $25 million, if invested in the region through education, equipment buyout, and job placement, could end the vaquita bycatch problem.<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

Studies performed in El Golfo de Santa Clara, one of the three major ports in which vaquitas live, indicated that gillnet fishing caused about 39 vaquita deaths a year in the late 1990s. This was close to 17% of the whole vaquita population within this port. While these results were not taken from the entire range of habitat in which vaquitas live, it is reasonable to assume that these results can be applied to the whole vaquita population, and in fact may even be a little low.<ref name="D'agrosa2000">{{Cite journal | last1 = d'Agrosa | first1 = C. | last2 = Lennert-Cody | first2 = C. E. | last3 = Vidal | first3 = O. | doi = 10.1046/j.1523-1739.2000.98191.x | title = Vaquita bycatch in Mexico's artisanal gillnet fisheries: driving a small population to extinction | journal = [[Conservation Biology (journal)|Conservation Biology]]| volume = 14 | issue = 4 | pages = 1110–1119| date = August 2000 | pmid = | pmc = }}</ref> Even with a gillnet ban throughout the vaquita refuge area, which contains 50% of the vaquita's habitat, the population is still in decline, which suggests a complete ban of gillnet use may be the only solution to saving the vaquita population.<ref name="Gerrodette2011">{{Cite journal | last1 = Gerrodette | first1 = T. | last2 = Taylor | first2 = B. L. | last3 = Swift | first3 = R. | last4 = Rankin | first4 = S. | last5 = Jaramillo-Legorreta | first5 = A. M. | last6 = Rojas-Bracho | first6 = L. | doi = 10.1111/j.1748-7692.2010.00438.x | title = A combined visual and acoustic estimate of 2008 abundance, and change in abundance since 1997, for the vaquita, ''Phocoena sinus''| journal = Marine Mammal Science | volume = 27 | issue = 2 | pages = E79–E100| year = 2011 | pmid = | pmc = | url = http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1270&context=usdeptcommercepub }}</ref> However, even in the face of all-encompassing gillnet bans, a significant number of Mexican fishermen in El Golfo de Santa Clara continue to use the nets. As many as a third of the area's fishermen are thought to still be using gillnets despite the imposition of bans on their use.<ref>''Report of the Fourth Meeting of the International Committee for the Recovery of the Vaquita (CIRVA)''. CIRVA, 2011, pp. 1–47, ''Report of the Fourth Meeting of the International Committee for the Recovery of the Vaquita (CIRVA)''.</ref> Trawl nets commonly used to catch shrimp in the area may also present threats due to their impacts on the Gulf's ecosystem, either directly through bycatch or by indirectly altering the seafloor and associated species (including vaquita prey).<ref name=":1"/> |

|||

Other potential threats to the vaquita population include [[habitat alteration]]s and [[pollutant]]s. The habitat of the vaquita is small and the food supply in marine environments is affected by water quality and nutrient levels. The damming of the [[Colorado River#Course|upper Colorado River]] has reduced the flow of fresh water into the gulf, though there is no empirical evidence that the reduced flow from the Upper Colorado River has posed an immediate short-term risk to the species.<ref name=":1">Rojas-Bracho, Lorenzo; Reeves, Randall R.; Jaramillo-Legorreta, Armando (2006). "Conservation of the vaquita Phocoena sinus". ''Mammal Review''. 36, No. 3: 179–216 – via JSTOR.</ref> In addition, the use of chlorinated pesticides may also have a detrimental effect. Despite these possible problems, most of the recovered bodies of vaquitas show no signs of emaciation or environmental stressors,<ref name="Rojas1" /> implying that the decline is due almost solely to [[bycatch]]. However, these additional hazards may pose a long-term threat. |

|||

A 2018 interview indicated that the illegal fishermen may be waiting for the species to go extinct in order to fish with fewer restrictions.<ref name = "Monga2018.03" /> |

|||

=== Secondary impact of declining numbers === |

|||

Though the major cause of vaquita porpoise mortality is bycatch in gillnets, as numbers continue to dwindle, new problems will arise that will tend to make recovery more difficult. One such problem is reduced breeding rates. With fewer individuals in the habitat, less contact will occur between the sexes and consequently less reproduction. This may be followed by increased inbreeding and reduced [[genetic variability]] in the [[gene pool]], following the [[population bottleneck|bottleneck effect]]. |

|||

When [[inbreeding depression]] occurs, the population experiences reduced [[Fitness (biology)|fitness]] because [[Mutation#By effect on fitness|deleterious]] [[recessive genes]] can manifest in the population. In small populations where genetic variability is low, individuals are more genetically similar. When the genomes of mating pairs are more similar, recessive traits appear more often in offspring. The more related two individuals are in the breeding pair, the more deleterious [[Homozygous|homozygous genes]] the offspring will likely have which can greatly lower fitness in the offspring.<ref name = "CIRVA">CIRVA committee, [http://www.iucn-csg.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/Report-of-the-Fourth-Meeting-of-the-International-Committee-for-the-Recovery-of-Vaquita.pdf Report of the Fourth Meeting of the International Committee for the Recovery of the Vaquita (CIRVA)]. [[IUCN]]. 2012</ref> These secondary impacts of dwindling vaquita numbers are not necessarily a threat yet, but they will become problematic if the population continues to decline.<ref name="Rojas-Bracho1999">{{Cite journal | last1 = Rojas-Bracho | first1 = L. | last2 = Taylor | first2 = B. L. | doi = 10.1111/j.1748-7692.1999.tb00873.x | title = Risk factors affecting the vaquita (''Phocoena sinus'')| journal = Marine Mammal Science | volume = 15 | issue = 4 | pages = 974–989 | date = October 1999 | pmid = | pmc = }}</ref> In addition, because porpoise population growth rates are generally low, the vaquita population is unlikely to recover rapidly even after the removal of anthropogenic risk factors to their survival. By some estimates, the maximum potential growth rate for the species is under 4%.<ref name=":1" /> However, the sighting of a female with a newborn calf in 2017 and the same female with another newborn in 2018 indicates that the species may have a relatively faster annual growth rate.<ref name=":2" /> |

|||

===Ecological consequences=== |

|||

Removal of the vaquita will have a significant ecological impact on the northern Gulf of California. The Gulf of California is considered a [[large marine ecosystem]], due to its high [[species diversity]] and large habitat size.<ref name="DiazUribe2012">{{Cite journal | last1 = Díaz-Uribe | first1 = J. G. | last2 = Arreguín-Sánchez | first2 = F. | last3 = Lercari-Bernier | first3 = D. | last4 = Cruz-Escalona | first4 = V. C. H. | last5 = Zetina-Rejón | first5 = M. J. | last6 = Del-Monte-Luna | first6 = P. | last7 = Martínez-Aguilar | first7 = S. | title = An integrated ecosystem trophic model for the North and Central Gulf of California: An alternative view for endemic species conservation | doi = 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2012.01.009 | journal = Ecological Modelling | volume = 230 | pages = 73–91| date = 10 April 2012 | pmid = | pmc = }}</ref> With such [[biodiversity]] in the region, it is important to consider the potentially harmful effects of drops in the vaquita population on seemingly unrelated species due to [[Apparent competition#By mechanism|apparent competition]]. |

|||

Sharks have been determined to be the only predators of vaquitas. Because of its limited number of predator species, the vaquita population is sensitive to small changes in predation from sharks.<ref name="DiazUribe2012"/> Although the vaquita accounts for only a small percentage of the diets of sharks in the region, extinction of the vaquita could potentially cause negative effects on shark population sizes. Extinction of the vaquita may also impact the vaquita prey populations in the northern Gulf ecosystem. The disappearance of the vaquita could lead to potential [[over-population]] of their prey species such as benthic fishes, squid, and crustaceans.<ref name="Rojas1" /> |

|||

Conservation efforts for the vaquita are mainly focused on fishing restrictions to prevent their bycatch. These fishing restrictions could prove beneficial for the fish in the upper Gulf, as well as the vaquita. As a result of increased restrictions on gillnet use, the populations of the targeted fish and shrimp species will receive protection from overfishing.<ref name="Elton">{{cite journal|last=Elton|first=Catherine|title=Safety Net|journal=Audubon|date=November–December 2011|volume=113|issue=6|pages=74–80|url=http://www.audubonmagazine.org/articles/conservation/safety-net-0|accessdate=20 January 2014}}</ref> Historically, numerous [[Commercial fishing|commercially fished]] species have experienced devastating impacts due to overfishing, and the vaquita conservation program may lessen the severity of such devastation in the future.<ref name="Elton" /> Another solution to prevent vaquita bycatch might be to redesign [[fishing nets]], which could be used to effectively catch fish, but leave the vaquita untouched. |

|||

=== Recovery efforts === |

|||

Because vaquitas are [[endemic]] to the Gulf of California, [[Mexico]] is leading conservation efforts with the creation of the International Committee for the Recovery of the Vaquita (CIRVA), which has tried to prevent the accidental deaths of vaquitas by outlawing the use of fishing nets within the vaquita's habitat.<ref name="barlow"/> CIRVA has worked with the CITES, the [[Endangered Species Act|ESA]], and the [[Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972|Marine Mammal Protection Act]] to make a plan to nurse the vaquita population back to a point at which they can sustain themselves.<ref name = NOAA_Vaquita>{{cite web|title= Vaquita / Gulf of California Harbor Porpoise / Cochito (''Phocoena sinus'')|url= http://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/pr/species/mammals/porpoises/vaquita.html |publisher=NOAA Fisheries Office of Protected Resources|work= Species Information|date= 8 July 2013|accessdate=20 January 2014}}</ref> CIRVA concluded in 2000 that between 39 and 84 individuals were killed annually by such gillnets. To try to prevent extinction, the Mexican government has created a nature reserve covering the upper part of the Gulf of California and the [[Colorado River delta]]. CIRVA recommends that this reserve be extended southwards to cover the full known area of the vaquita's range and that trawlers be completely banned from the reserve area. |

|||

On 28 October 2008, Canada, Mexico, and the United States launched the North American Conservation Action Plan (NACAP) for the vaquita, under the jurisdiction of the Commission for Environmental Cooperation, a NAFTA environmental organization.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.cec.org/our-work/projects/recovering-vaquita-and-promoting-sustainable-local-livelihoods|title=Recovering the Vaquita and Promoting Sustainable Local Livelihoods: Project Summary|publisher=Commission for Environmental Cooperation|year=2011|accessdate=5 November 2011}}</ref> The NACAP is a strategy to support Mexico's efforts to recover the vaquita. Also in 2008, Mexico launched the program PACE-VAQUITA, another effort to help preserve the species. PACE-VAQUITA compensates fishermen who choose one of three alternatives: rent-out, switch-out, and buy-out. |

|||

In the rent-out option, fishermen acquire temporary contractual obligations to carry out conservation efforts. They are paid if they agree to terminate their fishing inside the vaquita refuge area. There is a penalty if fishermen breach the contract which includes getting their vessels taken by the government. The switch-out option provides fishermen with compensation for switching to vaquita-safe harvesting technology. Finally, the buy-back program compensates fisherman for permanently turning in their fishing permits, as well as their respective gear.<ref name="Gerrodette2006">{{Cite journal | last1 = Gerrodette | first1 = T. | last2 = Rojas-Bracho | first2 = L. | doi = 10.1111/j.1748-7692.2010.00449.x | title = Estimating the success of protected areas for the vaquita, ''Phocoena sinus'' | journal = Marine Mammal Science| volume = 27 | issue = 2 | pages = E101–E125 | date = 7 February 2011 | pmid = | pmc = | url = https://zenodo.org/record/1230748 }}</ref> In 2008, because of how few fisherman were enrolling in the switch-out option, PACE Vaquita added a yearly, short-term option for fishermen, letting them simply rent the vaquita-safe fishing equipment yearly for compensation. Then, in 2010, this option was broken down even further, giving fishermen the option of buying the vaquita-safe net, or paying the yearly rent, but for less compensation.<ref name="Avila-Forcada2011"/> Despite these efforts, the probability that these attempts at conservation will work is slim. Only about a third of fishermen in the area have accepted these terms so far. Some fishermen continue to fish in the protected areas despite the economic alternatives. Even measuring the population size of the vaquita will be difficult as the rarity of the vaquita bycatch will make it difficult to demonstrate the difference these programs are making.<ref name="Gerrodette2006"/> |

|||

In November 2014, [[Greenpeace UK]] launched a campaign urging its members to write to President Peña Nieto to extend the vaquita reserve to the full range of the species, as well as commence dialogue with the Chinese and US over the commercial transport and consumption of products from species that threaten the vaquita's future, such as the similarly sized totoaba fish which is used in [[Chinese medicine]].<ref>{{cite web|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20170115112807/http://www.greenpeace.org.uk/blog/oceans/last-chance-save-vaquita-20141124|archive-date= 2017-01-15 |url-status= dead|url= http://www.greenpeace.org.uk/blog/oceans/last-chance-save-vaquita-20141124|title=Last Chance to Save the Vaquita? |publisher=Greenpeace.org.uk |year=2014|accessdate=26 November 2014}}</ref> |

|||

In May 2015 Mexico authorized an emergency partial gillnet ban (which did not extend to the legal fishery for the Gulf corvina, ''[[Cynoscion]] othonopterus'') in the area of the vaquita's habitat, in an attempt to halt the decline in population. In December 2015, [[Sea Shepherd Conservation Society]] launched [[Operation Milagro (Sea Shepherd)|Operation Milagro]], a direct action campaign to patrol the gulf habitat to protect the endangered vaquita. Sea Shepherd partnered with the [[Mexican Navy]] in a joint effort to remove illegal nets, release trapped wildlife, obtain visual evidence of poaching in the area and conduct outreach with local communities and marine biologists.<ref>{{cite web|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20160416050019/https://seashepherd.org/milagro2/about-campaign/about-the-campaign.html |archive-date= 2016-04-16 |url-status= dead |url= http://www.seashepherd.org/milagro2/about-campaign/about-the-campaign.html|title= Operation Milagro III - Vaquita Porpoise Defense Campaign - About Campaign}}</ref> In the fall of 2016, a new international program to locate and remove illegal or abandoned fishing gear from the vaquita's range began work, finding 31 illegal gillnets in 15 days.<ref name = "CIRVA-8" /> On April 8, 2017, Sea Shepherd pulled its 200th gillnet from Mexican waters since the start of Operation Milagro III in December 2016.<ref>[https://web.archive.org/web/20170507112522/http://www.seashepherd.org/milagro3 "Operation Milagro III - Home"]. ''www.seashepherd.org''. Retrieved 2017-08-06.</ref> |

|||

Unfortunately, the gillnet ban seems to have disproportionately impacted legal fisheries, and had the unintended effect of pushing more local fishermen into the illegal totoaba fishery. This was exacerbated by problems with the program intended to compensate fishermen for the economic consequences of the ban; half of those funds were given to just a few individuals, while others received nothing.<ref name = "film2016-07">{{cite web | url = http://vaquitafilm.com/mexico-permanently-bans-gillnets-in-the-upper-gulf/ | title = Mexico Permanently Bans Gillnets in the Upper Gulf! | date = July 2016 | website = Souls of the Vermillion Sea (vaquitafilm.com) | publisher = Wild Lens Inc. | access-date = 2018-07-05}}</ref> This led to the annual rate of population decline increasing from ~34% before the ban to ~50% in the first year afterwards.<ref name = "film2017-02">{{cite web | url = http://vaquitafilm.com/official-cirva-report-is-released/ | title = Official CIRVA Report is Released | date = February 2017 | website = Souls of the Vermillion Sea (vaquitafilm.com) | publisher = Wild Lens Inc. | access-date = 2018-07-05}}</ref> |

|||

Since these measures failed to halt the decline, by February 2017 it was judged that a program placing a portion of the remaining population in protective captivity was needed to save the species. Additional measures considered necessary were extending a permanent gillnet ban to the legal covina fishery (which can provide cover for the illegal totoaba fishery), improving the enforcement of fisheries regulations and increasing penalties for violations, and accelerated development of alternative, vaquita-friendly fishing gear for local fishermen.<ref name = "CIRVA-8" /> The gillnet ban was scheduled to expire at the end of May 2017; as that date approached, a campaign among conservationists to extend the ban gathered force on social media, with celebrities getting involved.<ref name = "McGrath2017-05">{{cite web | url = https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-39923383 | title = Rare Mexican porpoise faces 'imminent extinction' | last = McGrath | first = Matt | date = 2017-05-16 | publisher = BBC | access-date = 2017-05-16}}</ref> |

|||

On 7 June 2017, it was announced by President [[Peña Nieto]] that the gillnet ban would be extended and made permanent.<ref name = "S.D.Union-Tribune2017"/><ref name = "None listed 2017-07">{{cite web | url = https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-40466607 | title = Vaquita porpoise: Dolphins deployed to save rare species | last = | first = | date = 2017-07-01 | publisher = BBC | access-date = 2017-07-02}}</ref> There will also be newly strengthened efforts to enforce the ban and prosecute violators. To discourage skirting the rules, fishing at night will be prohibited and monitored entry and exit points will be established for fishing vessels that operate in the protected zone. The agreement was signed by the president as well as the Mexican secretaries for the environment, agriculture and navy. The foundations of Mexican businessman [[Carlos Slim]] and American actor and environmental activist [[Leonardo DiCaprio]] also pledged to support implementation of the plan.<ref name = "S.D.Union-Tribune2017"/> |

|||

While the permanent ban and increased fishing regulations, if properly enforced, will help preserve the vaquita population, they do not resolve the economic situation. The fishermen may rely on solely this business to make a living. The regulations do not address the traditions and livelihoods of the community that is dependent on fishing. Programs are needed that educate members of the community about conservation and facilitate economic diversification. Conservation groups have contributed to the rise of ecotourism around the world, as it is an immersive way to educate the public about conservation of endangered species and expose visitors to their natural habitat that also faces imminent threat. However, a decreased reliance on fish consumption altogether will have the greatest impact on the vaquitas and other endangered species threatened by the risk of bycatch.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Aburto‐Oropeza |first=Octavio |last2=López‐Sagástegui|first2=Catalina|last3=Moreno‐Báez|first3=Marcia|last4=Mascareñas‐Osorio|first4=Ismael|last5=Jiménez‐Esquivel |first5=Victoria |last6=Johnson|first6=Andrew Frederick|last7=Erisman|first7=Brad|date=2018-01-01|title=Endangered Species, Ecosystem Integrity, and Human Livelihoods|journal=Conservation Letters |language=en |volume=11 |issue=1 |pages=e12358 |doi=10.1111/conl.12358 |issn=1755-263X}}</ref> |

|||

The proposal for a [[captive breeding]] program must contend with the general greater difficulty of keeping porpoises in captivity relative to dolphins, due to porpoises' sensitivity to disturbance and stress.<ref name="Goldfarb2016b">{{cite journal |last1=Goldfarb |first1=B. |title=Can captive breeding save Mexico's vaquita?|journal= Science|volume= 353|issue= 6300|date= 2016-08-12 |pages= 633–634 |doi= 10.1126/science.353.6300.633|pmid= 27516576}}</ref> Success in keeping captive porpoises has only been attained in recent years.<ref name="Goldfarb2016b" /> The scheme involves the use of [[United States Navy Marine Mammal Program|trained dolphins of the U.S. Navy]] to locate the vaquitas, along with aircraft and a spotter vessel with an observation tower. Vaquitas would be captured with a light salmon gillnet.<ref name="Morell2017" /><ref name="2017-10-05_MT">[https://www.militarytimes.com/news/your-navy/2017/10/06/experts-to-start-capturing-rare-vaquita-porpoises-in-mexico/ Experts to start capturing rare vaquita porpoises in Mexico], Mark Stevenson, [[The Associated Press]] / MilitaryTimes.com, 2017-10-05</ref> Some of these vaquitas might be satellite-tagged and released for research purposes, while others would be kept captive. The latter vaquitas would be transferred to sea pens along the shore of the gulf, with large pools on land also available for special care if needed. Once success was attained in the campaign to eliminate the threat of gillnets, captive vaquitas could then be released back into the wild.<ref name = "CIRVA-8" /> |

|||

This program, called VaquitaCPR (Vaquita Conservation, Protection, and Recovery), began capturing vaquitas from the Gulf in autumn of 2017. However, the initial two attempts resulted in the death of one vaquita.<ref>[http://www.nmmf.org/vaquitacpr.html "Vaquita Conservation, Protection and Recovery"]. ''National Marine Mammal Foundation''. Retrieved 2017-08-06.</ref><ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2017/11/update-after-death-captured-vaquita-conservationists-call-rescue-effort|title=Update: After death of captured vaquita, conservationists call off rescue effort|date=2017-10-12|work=Science {{!}} AAAS|access-date=2018-03-08|language=en}}</ref> On 6 November 2017, Mexico's environmental minister announced that a female vaquita had been successfully captured and brought to an enclosure, but had died several hours later, evidently due to stress.<ref name = "BBC 2017-11-06">{{cite web | url = https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-41886417 | title = Endangered Mexican vaquita dies after rescue effort | last = | first = | date = 2017-11-06 | publisher = BBC | access-date = 2017-11-06}}</ref> The breeding program was closed soon after, and in February 2018, a program conceived in 2017 was funded, which would breed totoaba in three dedicated fish farms to reduce the size of the totoaba black market and thus decrease accidental vaquita killings.<ref>[http://www.seafoodnews.com/Story/1092096/Totoaba-Farming-May-Help-Vaquita-Porpoise Totoaba Farming May Help Vaquita Porpoise]. ''Food News''. 13 February 2018</ref><ref>[https://translate.google.com/translate?hl=en&sl=es&tl=en&u=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.excelsior.com.mx%2Fnacional%2F2017%2F08%2F22%2F1183227 Semarnat issues marking rules for Totoaba raised in captivity]. (Automated translation from Spanish) Ernesto Méndez, ''Excelsior''. 22 August 2017.</ref><ref>[http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-02/10/c_136963548.htm Mexico to create fish farms to save vaquita porpoise from extinction]. ''Xinhua News''. 10 February 2018.</ref> |

|||

Recovery efforts have been deemed very slow and inadequate, with large amounts of poaching still going on, reducing the population to one dozen. [[Sea Shepherd Conservation Society|Sea Shepherd]] and [[Elephant Action League]] are apparently the only organizations to have a constant presence in monitoring the population.<ref name = "Monga2018.03" /> |

|||

Based on the extremely small range the species has been reduced to as of 2018, it may actually become easier to conserve the remaining population, although this restricted range makes it more vulnerable to illegal fishing in the case of incursion into this area. Potential suggestions to conserve the species include stationing a permanent military vessel in the area or forming a floating barrier of above-water nets to prevent illegal fishing boats from such incursions. Experts have also called on Mexico's incoming president, [[Andrés Manuel López Obrador|Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador]], to put forth policies conserving the species. However, Obrador's plans for job-creation (likely including promotion of the fishing industry) may debase efforts to protect the species, and Josefa González, Obrador's pick for the Environment Department, has implied that she sees vaquita conservation as a lost cause.<ref name=":3" /> |

|||

On 1 February 2019, [[Sea Shepherd]] reported that one of its boats patrolling the area to remove and deter the setting of illegal nets had been attacked by fishing boats for the second time in a month.<ref name = "AP2019-02-01">{{cite news |url= https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/the_americas/sea-shepherd-ship-attacked-in-mexicos-gulf-of-california/2019/02/01/4f5481c0-2686-11e9-b5b4-1d18dfb7b084_story.html| title= Sea Shepherd ship attacked in Mexico’s Gulf of California |date= 2019-02-01|website= washingtonpost.com |agency= Associated Press| access-date= 2019-02-04}}</ref> It has also been reported that the efforts of the Mexican navy to deter illegal fishing have not been successful; the fishermen intimidate the navy by ramming their boats and while the navy has given chase they have not responded with force. Some fishermen are apparently becoming desperate because they have found it necessary to borrow money from trafficking cartels to replace their illegal nets.<ref name = "MND2019.03.07" /> On 13 March 2019 it was announced that around 10 vaquitas were left, after Sea Shepherd found one of the porpoises had drowned in a gillnet, which was likely set out for totoaba fish.<ref name="mb1">{{cite web |title=Possible vaquita death accompanies announcement that only 10 are left |url=https://news.mongabay.com/2019/03/possible-vaquita-death-as-scientists-say-only-10-are-left/ |website=Mongabay.com | date = 18 March 2019 |accessdate=23 April 2019}}</ref> A possible recovery was not ruled out, as calves are still seen. |

|||

== See also == |

|||

{{Portal|Cetaceans|Mammals|Marine life}} |

|||

* [[List of cetacean species]] |

|||

* [[Marine biology]] |

|||

* [[Sea of Shadows]] |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{ARKive attribute}} |

|||

{{Reflist | colwidth = 30em}} |

{{Reflist | colwidth = 30em}} |

||

| Line 146: | Line 77: | ||

| title = Vaquita: The Business of Extinction (article and 25-min. documentary video) |

| title = Vaquita: The Business of Extinction (article and 25-min. documentary video) |

||

| last = Alcántara | first = A. | date = December 2017 | publisher = CNN | access-date = 2017-12-07}} |

| last = Alcántara | first = A. | date = December 2017 | publisher = CNN | access-date = 2017-12-07}} |

||

* {{cite book |last1= |

* {{cite book |last1=Bessesen |first1=Brooke |date = September 2018 |title=Vaquita: Science, Politics, and Crime in the Sea of Cortez |publisher=Island Press |isbn= 9781610919326 |url=https://islandpress.org/books/vaquita}} |

||

* {{cite web |

|||

|last = Culik |

|||

|first = B. |

|||

|year = 2010 |

|||

|title = ''Phocoena sinus'' |

|||

|work = Odontocetes: The toothed whales |

|||

|publisher = UNEP/Convention on Migratory Species Secretariat |

|||

|url = http://www.cms.int/reports/small_cetaceans/data/P_sinus/p_sinus.htm |

|||

|accessdate = 20 January 2014 |

|||

|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20150417155759/http://www.cms.int/reports/small_cetaceans/data/P_sinus/p_sinus.htm |

|||

|archive-date = 17 April 2015 |

|||

|url-status = dead |

|||

|df = dmy-all |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite journal | title = Goodbye, Vaquita: How Corruption and Poverty Doom Endangered Species |

* {{cite journal | title = Goodbye, Vaquita: How Corruption and Poverty Doom Endangered Species |

||

| journal = Scientific American |

| journal = Scientific American |

||

| Line 174: | Line 91: | ||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

{{Commons category|Phocoena sinus}} |

{{Commons category|Phocoena sinus}} |

||

To learn more about the vaquita and conservation efforts visit: |

|||

{{Wikispecies|Phocoena sinus}} |

|||

* [http://vaquitafilm.com/ The Vaquita and the Totoaba] - web site for the Wild Lens Collective of film makers' outreach campaign about the vaquita's extinction crisis |

|||

*[http://www.vivavaquita.org ¡Viva Vaquita!] – a non-profit organization dedicated to preventing the extinction of the vaquita |

|||