Presidency of Jimmy Carter: Difference between revisions

m Task 14: cs1 template fixes: misused |publisher= (1×/2×); |

→Environment: Citation |

||

| Line 293: | Line 293: | ||

=== Environment === |

=== Environment === |

||

Carter supported many of the goals of the environmentalist movement, and he signed several bills that were designed to protect the environment.<ref>Patterson, p. 118</ref> In 1977, Carter signed the [[Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977]], which regulates strip mining.<ref name="millerdomestic"/> In 1980 Carter signed into law a bill that established [[Superfund]], a federal program designed to clean up sites contaminated with hazardous substances.<ref> |

Carter supported many of the goals of the environmentalist movement, and he signed several bills that were designed to protect the environment.<ref>Patterson, p. 118</ref> In 1977, Carter signed the [[Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977]], which regulates strip mining.<ref name="millerdomestic"/> In 1980 Carter signed into law a bill that established [[Superfund]], a federal program designed to clean up sites contaminated with hazardous substances.<ref>Byron W.Daynes, and Glen Sussman. ''White House Politics and the Environment: Franklin D. Roosevelt to George W. Bush'' (2010) pp 84-10om [https://www.amazon.com/White-House-Politics-Environment-Presidency/dp/1603442030 Excerpt]</ref> |

||

[[Cecil Andrus]] who had been governor of Idaho, served as secretary of the interior 1978-81. He convinced Carter to withdraw nearly half of 375 million acres of public domain land from commercial use in a series of executive moves and new laws. In December 1978 the president placed more 56 million acres of the state's Federal lands into the National Park system, protecting them from mineral or oil development The 1980 [[Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act]], doubled the amount of public land set aside for national parks and wildlife refuges. Carter used his power under the 1906 Antiquities Act to set aside 57 million acres in 17 national monuments. The remaining acres were withdrawn under the 1976 Federal Land Policy and Management Act.<ref>Stephen W. Haycox, ''The Politics of Environment: Cecil Andrus and the Alaska Lands Act," ''Idaho Yesterdays'' 36#3 (Fall 1992) , pp 28-36. </ref> <ref> See [https://www.nytimes.com/1978/12/02/archives/carter-designates-us-land-in-alaska-for-national-parks-56-million.html Seth S. King, "Carter Designates U.S. Land In Alaska For National Parks," ''New York Times'', Dec 2, 1978]</ref> Business and conservative interests complained that economic growth would be hurt.<ref>Timo Christopher Allan, "Locked up!: A history of resistance to the creation of national parks in Alaska" (PhD dissertation Washington State University, 2010). [http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.633.9906&rep=rep1&type=pdf online]</ref> |

[[Cecil Andrus]] who had been governor of Idaho, served as secretary of the interior 1978-81. He convinced Carter to withdraw nearly half of 375 million acres of public domain land from commercial use in a series of executive moves and new laws. In December 1978 the president placed more 56 million acres of the state's Federal lands into the National Park system, protecting them from mineral or oil development The 1980 [[Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act]], doubled the amount of public land set aside for national parks and wildlife refuges. Carter used his power under the 1906 Antiquities Act to set aside 57 million acres in 17 national monuments. The remaining acres were withdrawn under the 1976 Federal Land Policy and Management Act.<ref>Stephen W. Haycox, ''The Politics of Environment: Cecil Andrus and the Alaska Lands Act," ''Idaho Yesterdays'' 36#3 (Fall 1992) , pp 28-36. </ref> <ref> See [https://www.nytimes.com/1978/12/02/archives/carter-designates-us-land-in-alaska-for-national-parks-56-million.html Seth S. King, "Carter Designates U.S. Land In Alaska For National Parks," ''New York Times'', Dec 2, 1978]</ref> Business and conservative interests complained that economic growth would be hurt.<ref>Timo Christopher Allan, "Locked up!: A history of resistance to the creation of national parks in Alaska" (PhD dissertation Washington State University, 2010). [http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.633.9906&rep=rep1&type=pdf online]</ref> |

||

Revision as of 02:01, 26 June 2019

| |

| Presidency of Jimmy Carter January 20, 1977 – January 20, 1981 | |

Jimmy Carter | |

| Cabinet | See list |

| Party | Democratic |

| Election | 1976 |

| Seat | White House |

|

| |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

76th Governor of Georgia

39th President of the United States

Policies

Appointments

Tenure

Presidential campaigns Post-presidency

|

||

The presidency of Jimmy Carter began at noon EST on January 20, 1977, when Jimmy Carter was inaugurated as the 39th President of the United States, and ended on January 20, 1981. Carter, a Democrat, took office after defeating incumbent Republican President Gerald Ford in the 1976 presidential election. His presidency ended with his defeat in the 1980 presidential election by Republican nominee Ronald Reagan.

Carter took office during a period of "stagflation", as the economy experienced a combination of high inflation and slow economic growth. His budgetary policies centered on taming inflation by reducing deficits and government spending. Responding to energy concerns that had persisted through much of the 1970s, his administration enacted a national energy policy designed to promote energy conservation and the development of alternative resources. Despite Carter's policies, the country was beset by an energy crisis in 1979, which was followed by a recession in 1980. Carter sought reforms to the country's welfare, health care, and tax systems, but was largely unsuccessful, partly due to poor relations with Congress. He presided over the establishment of the Department of Energy and the Department of Education.

Taking office in the midst of the Cold War, Carter reoriented U.S. foreign policy towards an emphasis on human rights. Taking office during a period of relatively warm relations with both China and the Soviet Union, Carter continued the conciliatory policies of his predecessors. He normalized relations with China and continued the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks with the Soviet Union. In an effort to end the Arab–Israeli conflict, he helped arrange the Camp David Accords between Israel and Egypt. Through the Torrijos–Carter Treaties, Carter guaranteed the transfer of the Panama Canal to Panama in 1999. After the start of the Soviet–Afghan War, he discarded his conciliatory policies towards the Soviet Union and began a period of military build-up.

The final fifteen months of Carter's presidential tenure were marked by several major crises, including the Iran hostage crisis, serious fuel shortages, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. His low approval ratings drew a challenge from Ted Kennedy, a prominent liberal Democrat who protested Carter's opposition to a national health insurance system. Boosted by public support for his policies in late 1979 and early 1980, Carter rallied to defeat Kennedy in the 1980 Democratic primaries. In the general election, Carter faced Reagan, a conservative former governor of California. Though polls taken on the eve of the election showed a close race, Reagan won a decisive victory. In polls of historians and political scientists, Carter is usually ranked as a below-average president.

Presidential election of 1976

Carter was elected as the Governor of Georgia in 1970, and during his four years in office he earned a reputation as a progressive, racially moderate Southern governor. Observing George McGovern's success in the 1972 Democratic primaries, Carter came to believe that he could win the 1976 Democratic presidential nomination by running as an outsider unconnected to establishment politicians in Washington, D.C.[1] Despite scant backing from party leaders, McGovern had won the 1972 Democratic nomination by winning delegates in primary elections, and Carter's campaign would follow a similar course.[2] Carter declared his candidacy for the 1976 Democratic presidential nomination in December 1974.[3] As Democratic leaders such as 1968 nominee Hubert Humphrey, Senator Walter Mondale of Minnesota, and Senator Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts declined to enter the race, there was no clear favorite in the Democratic primaries. Mo Udall, Sargent Shriver, Birch Bayh, Fred R. Harris, Terry Sanford, Henry M. Jackson, Lloyd Bentsen, and George Wallace all sought the nomination, and many of these candidates were better known than Carter.[4]

Carter sought to appeal to various groups in the party; his advocacy for cutting defense spending and reining in the CIA appealed to liberals, while his emphasis on eliminating government waste appealed to conservatives.[5] Iowa held the first contest of the primary season, and Carter campaigned heavily in the state, hoping that a victory would show that he had serious chance of winning the nomination. Carter won the most votes of any candidate in the Iowa caucus, and he dominated media coverage in advance of the New Hampshire primary, which he also won.[6] Carter's subsequent defeat of Wallace in the Florida and North Carolina primaries eliminated Carter's main rival in the South.[7] The support of black voters was a key factor in Carter's success, especially in the Southern primaries. With a victory over Jackson in the Pennsylvania primary, Carter established himself as the clear front-runner.[8] Despite the late entrance of Senator Frank Church and Governor Jerry Brown into the race, Carter clinched the nomination on the final day of the primaries.[9] The 1976 Democratic National Convention proceeded harmoniously and, after interviewing several candidates, Carter chose Mondale as his running mate. The selection of Mondale was well received by many liberal Democrats, who had been skeptical of Carter.[10]

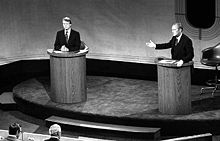

The Republicans experienced a contested convention that ultimately nominated incumbent President Gerald Ford, who had succeeded to the presidency in 1974 after the resignation of Richard Nixon due to the latter's involvement in the Watergate scandal.[10] With the Republicans badly divided, and with Ford facing questions over his competence as president, polls taken in August 1976 showed Carter with a 15-point lead.[11] In the general election campaign, Carter continued to promote a centrist agenda, seeking to define new Democratic positions in the aftermath of the tumultuous 1960s. Above all, Carter attacked the political system, defining himself as an "outsider" who would reform Washington in the post-Watergate era.[12] In response, Ford attacked Carter's supposed "fuzziness", arguing that Carter had taken vague stances on major issues.[11] Carter and President Ford faced off in three televised debates during the 1976 election,[13] the first such debates since 1960.[13] Ford was generally viewed as the winner of the first debate, but he made a major gaffe in the second debate when he stated there was "no Soviet domination of Eastern Europe."[a] The gaffe put an end to Ford's late momentum, and Carter helped his own campaign with a strong performance in the third debate. Polls taken just before election day showed a very close race.[14]

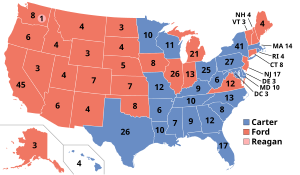

Carter won the election with 50.1% of the popular vote and 297 electoral votes, while Ford won 48% of the popular vote and 240 electoral votes. The 1976 presidential election represents the lone Democratic presidential election victory between the elections of 1964 and 1992. Carter fared particularly well in the Northeast and the South, while Ford swept the West and won much of the Midwest. In the concurrent congressional elections, Democrats increased their majorities in both the House and Senate.[15]

Inauguration

In his inaugural address, Carter said, "We have learned that more is not necessarily better, that even our great nation has its recognized limits, and that we can neither answer all questions nor solve all problems."[16] Carter had campaigned on a promise to eliminate the trappings of the "Imperial Presidency", and began taking action according to that promise on Inauguration Day, breaking with recent history and security protocols by walking from the Capitol to the White House in his inaugural parade. His first steps in the White House went further in this direction: Carter cut the size of the 500-member White House staff by one-third and reduced the perks for the president and cabinet members.[17] He also fulfilled a campaign promise by issuing a "full complete and unconditional pardon" (amnesty) for Vietnam War-era draft evaders. The draft had become unpopular and was abolished by Nixon; evaders were not hared and dropping charges against him as part of the healing process that Ford had started and Carter continued. However, deserters were much more controversial, and their cases were examined individually.[18]

Administration

Though Carter had campaigned against Washington insiders, most of his top appointees had served in previous administrations or had known Carter in Georgia.[19] Secretary of State Cyrus Vance, Secretary of Defense Harold Brown, and Secretary of the Treasury W. Michael Blumenthal had been high-ranking officials in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations.[20] Other notable appointments included Charles Schultze as Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, former Secretary of Defense James R. Schlesinger as a presidential assistant on energy issues, federal judge Griffin Bell as Attorney General, and Patricia Roberts Harris, the first African-American woman to serve in the cabinet,[21] as Secretary of Housing and Urban Development.[22]

After his victory in the 1976 election, Carter offered the position of White House Chief of Staff to two of his advisers, Hamilton Jordan and Charles Kirbo, but both declined. Carter decided not to have a chief of staff, instead implementing a system in which cabinet members would have more direct access to the president.[23] Carter appointed several close associates from Georgia to staff the Executive Office of the President. Bert Lance was selected to lead the Office of Management and Budget, while Jordan became a key aide and adviser. Other appointees from Georgia included Jody Powell as White House Press Secretary, Jack Watson as cabinet secretary, and Stuart E. Eizenstat as head of the Domestic Policy Staff.[24] To oversee the administration's foreign policy, Carter relied on several members of the Trilateral Commission, including Vance and National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski. Brzezinski emerged as one of Carter's closest advisers, and Carter made use of both the National Security Council and Vance's State Department in developing and implementing foreign policy.[25] Vice President Mondale served as a key adviser on both foreign and domestic issues,[26] and First Lady Rosalynn Carter emerged as a key player, sitting in some cabinet meetings, and on a daily basis was president sounding board, advisor, and surrogate. She traveled abroad to negotiate foreign policy, and became tied with Mother Teresa as the most admired woman in the world.[27]

Carter shook up the White House staff in mid-1978, bringing in advertising executive Gerald Rafshoon to serve as the White House Communications Director and Anne Wexler to lead the Office of Public Liaison.[28] Carter implemented broad personnel changes in the White House and cabinet in mid-1979. Five cabinet secretaries left office, including Blumenthal, Bell, and Joseph Califano, the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare. Jordan was selected as the president's first chief of staff, while Alonzo L. McDonald, formerly of McKinsey & Company, became the White House staff director. Federal Reserve Chairman G. William Miller replaced Blumenthal as Secretary of the Treasury, Benjamin Civiletti took office as Attorney General, and Charles Duncan Jr. became Secretary of Energy.[29] After Vance resigned in 1980, Carter appointed Edmund Muskie, a well-respected Senator with whom Carter had developed friendly relations, to serve as Secretary of State.[30]

Judicial appointments

Among presidents who served at least one full term, Carter is the only one who never made an appointment to the Supreme Court.[31] Carter appointed 56 judges to the United States Courts of Appeals, and 203 judges to the United States district courts. Two of his circuit court appointees – Stephen Breyer and Ruth Bader Ginsburg – were later appointed to the Supreme Court by Bill Clinton. Carter was the first president to make demographic diversity a key priority in the selection of judicial nominees.[32] During Carter's presidency, the number of female circuit court judges increased from one to twelve, the number of non-white male circuit judges increased from six to thirteen, the number of female district court judges increased from four to 32, and the number of non-white male district court judges increased from 23 to 55. Carter appointed the first female African-American circuit court judge, Amalya Lyle Kearse, the first Hispanic circuit court judge, Reynaldo Guerra Garza, and the first female Hispanic district court judge, Carmen Consuelo Cerezo.[33]

Domestic affairs

Carter was not a product of the New Deal traditions of liberal Northern Democrat, and traced his ideological background to the Progressive Era. British historian Iwan Morgan argues:

- Carter traced his political values to early twentieth-century southern progressivism with its concern for economy and efficiency in government and compassion for the poor. He described himself as a fiscal conservative, but liberal on matters like civil rights, the environment, and "helping people to overcome handicaps to lead fruitful lives," an ideological construct that appeared to make him the legatee of Dwight Eisenhower rather than Franklin D. Roosevelt. [34]

Carter was thus much more conservative than the dominant liberal wing of the party could accept. Intellectuals, who were much closer to the New Deal heritage. and labor unions, were increasingly hostile. The ideological opposition to Carter within the party was increasingly led by Senator Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts. Kennedy did challenge Carter for the nomination in 1980, but ran a weak campaign and was badly defeated in the primaries.[35]

Relations with Congress

Carter successfully campaigned as a Washington "outsider" critical of both President Gerald Ford and the Democratic Congress; as president, Carter continued this theme. It was this refusal to play by the rules of Washington, however, which contributed to the Carter administration's difficult relationship with Congress. After the election, Carter demanded the power to reorganize the executive branch, alienating powerful Democrats like Speaker Tip O'Neill and Jack Brooks. During the Nixon administration, Congress had passed a series of reforms that removed power from the president, and most members of Congress were unwilling to restore that power even with a Democrat now in office.[36][b] Unreturned phone calls, verbal insults, and an unwillingness to trade political favors soured many on Capitol Hill and affected the president's ability to enact his agenda.[38] In many cases, these failures of communication stemmed not from intentional neglect, but rather from poor organization of the administration's congressional liaison functions.[39] Carter attempted to woo O'Neill, Senate Majority Leader Robert Byrd, and other members of Congress through personal engagement, but he was generally unable to rally support for his programs through these meetings.[40] Carter also erred in focusing on too many priorities at once, especially in the first months of his presidency.[41]

A few months after his term started, and thinking he had the support of about 74 congressmen, Carter issued a "hit list" of 19 projects that he claimed were "pork barrel" spending. He said that he would veto any legislation that contained projects on this list.[42] Congress responded by passing a bill that combined several of the projects that Carter objected to with economic stimulus measures that Carter favored. Carter chose to sign the bill, but his criticism of the alleged "pork barrel" projects cost him support in Congress.[43] These struggles set a pattern for Carter's presidency, and he would frequently clash with Congress for the remainder of his tenure.[44]

Budget policies

On taking office, Carter proposed an economic stimulus package that would give each citizen a $50 tax rebate, cut corporate taxes by $900 million, and increase spending on public works. The limited spending involved in the package reflected Carter's fiscal conservatism, as he was more concerned with avoiding inflation and balancing the budget than addressing unemployment. Carter's resistance to higher federal spending drew attacks from many members of his own party, who wanted to lower the unemployment rate through federal public works projects. Carter signed several measures designed to address unemployment in 1977, including an extension of the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act, but he continued to focus primarily on reducing deficits and inflation. In November 1978, Carter signed the Revenue Act of 1978, an $18.7 billion tax cut.[45]

Federal budget deficits throughout Carter's term remained at around the $70 billion level reached in 1976, while falling as a percent of GDP from 4% to 2.5% by the 1980–81 fiscal year.[46] The national debt of the United States increased by about $280 billion, from $620 billion in early 1977 to $900 billion in late 1980.[47] However, because economic growth outpaced the growth in nominal debt, the federal government's debt as a percentage of gross domestic product decreased slightly, from 33.6% in early 1977 to 31.8% in late 1980.[48]

Energy

The energy crisis haunted Carter's entire term as it damaged the economy. International prices spiraled higher and higher, damaging the economy, where there was no good way to increase domestic production. Environmentalism became a powerful voice. After the nuclear near-disaster at Three Mile Island in 1979 Carter rejected nuclear power as a solution. He insisted that America cut back its energy consumption. His numerous plans were rejected by Congress, and he lacked public support.[49][50][51]

With domestic production declining, consumption increasing, Oil imports had soared since 1973, and the U.S. consumed over twice as much energy, per capita, as other developed countries.[44] In 1973, during the Nixon Administration, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), based in the Middle East, reduced output to raise world prices and to hurt Israel and its allies, including the United States.[52] This became the 1973 Oil Crisis and forced oil prices to rise sharply, forcing higher prices throughout the American economy and slowing growth.[53] The United States continued to face energy issues in the following years, and during the winter of 1976–1977 natural gas shortages forced the closure of many schools and factories, leading to the temporary layoffs of hundreds of thousands of workers.[54]

National Energy Act

By 1977, energy policy was one of the greatest challenges facing the United States. Oil imports had increased 65% annually since 1973, and the U.S. consumed over twice as much energy, per capita, as other developed countries.[44] In 1973, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), based in the Middle East, reduced its output of oil to raise prices and hurt Israel and its allies, including the United States. This caused the worldwide 1973 Oil Crisis with shortages and soaring prices. It caused price inflation throughout the world economy and slowed growth.[53] The United States continued to face energy issues in the following years, and during the winter of 1976–1977 natural gas shortages forced the closure of many schools and factories, leading to the temporary layoffs of hundreds of thousands of workers.[55]

Upon taking office, Carter asked James Schlesinger to develop a plan to address the energy crisis.[56] Carter also won congressional approval for the creation of the Department of Energy, and he named Schlesinger as the first head of that department. Schlesinger presented an energy plan that contained 113 provisions, the most important of which were taxes on domestic oil production and gasoline consumption. The plan also provided for tax credits for energy conservation, taxes on automobiles with low fuel efficiency, and mandates to convert from oil or natural gas to coal power.[57] The House approved much of Carter's plan in August 1977, but the Senate passed a series of watered-down energy bills that included few of Carter's proposals. Negotiations with Congress dragged on into 1978, but Carter signed the National Energy Act in November 1978. Many of Carter's original proposals were not included in the legislation, but the act deregulated natural gas and encouraged energy conservation and the development of renewable energy through tax credits.[58]

1979 energy crisis

Another energy shortage hit the United States in 1979, and millions of frustrated motorists were forced into long waits at gasoline stations. In response, Carter asked Congress to deregulate the price of domestic oil. At the time, domestic oil prices were not set by the world market, but rather by the complex price controls of the 1975 Energy Policy and Conservation Act (EPCA). Oil companies strongly favored the deregulation of prices, since it would increase their profits, but some members of Congress worried that deregulation would contribute to inflation. In late April and early May the Gallup poll found only 14 percent of the public believed that America was in an actual energy shortage. The other 77 percent believed that this was brought on by oil companies just to make a profit[59]. Carter paired the deregulation proposal with a windfall profits tax, which would return about half of the new profits of the oil companies to the federal government. Carter used a provision of EPCA to phase in oil controls, but Congress balked at implementing the proposed tax.[60] [61]

I want to talk to you right now about a fundamental threat to American democracy... I do not refer to the outward strength of America, a nation that is at peace tonight everywhere in the world, with unmatched economic power and military might. The threat is nearly invisible in ordinary ways. It is a crisis of confidence. It is a crisis that strikes at the very heart and soul and spirit of our national will. We can see this crisis in the growing doubt about the meaning of our own lives and in the loss of a unity of purpose for our nation...

Jimmy Carter[62]

In July 1979, as the energy crisis continued, Carter met with a series of business, government, labor, academic, and religious leaders in an effort to overhaul his administration's policies.[63] His pollster, Pat Caddell, told him that the American people faced a crisis of confidence stemming from the assassinations of major leaders in the 1960s, the Vietnam War, and the Watergate scandal.[64] Though most of his other top advisers urged him to continue to focus on inflation and the energy crisis, Carter seized on Caddell's notion that the major crisis facing the country was a crisis of confidence. On July 15, Carter delivered a nationally televised speech in which he called for long-term limits on oil imports and the development of synthetic fuels. But he also stated, "all the legislation in the world can't fix what's wrong with America. What is lacking is confidence and a sense of community."[65] The speech came to be known as his "malaise" speech, although Carter never used the word in the speech.[66]

The initial reaction to Carter's speech was generally positive, but Carter erred by forcing out several cabinet members, including Secretary of Energy Schlesinger, later in July.[67] Nonetheless, Congress approved a $227 billion windfall profits tax and passed the Energy Security Act. The Energy Security Act established the Synthetic Fuels Corporation, which was charged with developing alternative energy sources.[68] Despite those legislative victories, in 1980 Congress rescinded Carter's imposition of a surcharge on imported oil,[c] and rejected his proposed Energy Mobilization Board, a government body that was designed to facilitate the construction of power plants.[70] Nonetheless, Kaufman and Kaufman write that policies enacted under Carter represented the "most sweeping energy legislation in the nation's history."[68] Carter's policies contributed to a decrease in per capita consumption energy consumption, which dropped by 10 percent from 1979 to 1983.[71] Oil imports, which had reached a record 2.4 billion barrels in 1977 (50% of supply), declined by half from 1979 to 1983.[46]

Economy

| Year | Income | Outlays | Surplus/ Deficit |

GDP | Debt as a % of GDP[73] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1977 | 355.6 | 409.2 | -53.7 | 2028.4 | 27.1 |

| 1978 | 399.6 | 458.7 | -59.2 | 2278.2 | 26.6 |

| 1979 | 463.3 | 504.0 | -40.7 | 2570.0 | 24.9 |

| 1980 | 517.1 | 590.9 | -73.8 | 2796.8 | 25.5 |

| 1981 | 599.3 | 678.2 | -79.0 | 3138.4 | 25.2 |

| Ref. | [74] | [75] | [76] | ||

Carter took office during a period of "stagflation", as the economy experienced both high inflation and low economic growth.[77] The U.S. had recovered from the 1973–75 recession, but the economy, and especially inflation, continued to be a top concern for many Americans in 1977 and 1978.[78] The economy had grown by 5% in 1976, and it continued to grow at a similar pace during 1977 and 1978.[79] Unemployment declined from 7.5% in January 1977 to 5.6% by May 1979, with over 9 million net new jobs created during that interim,[80] and real median household income grew by 5% from 1976 to 1978.[81] In October 1978, responding to worsening inflation, Carter announced the beginning of "phase two" of his anti-inflation campaign on national television. He appointed Alfred E. Kahn as the Chairman of the Council on Wage and Price Stability (COWPS), and COWPS announced price targets for industries and implemented other policies designed to lower inflation.[82]

The 1979 energy crisis ended a period of growth; both inflation and interest rates rose, while economic growth, job creation, and consumer confidence declined sharply.[83] The relatively loose monetary policy adopted by Federal Reserve Board Chairman G. William Miller, had already contributed to somewhat higher inflation,[84] rising from 5.8% in 1976 to 7.7% in 1978. The sudden doubling of crude oil prices by OPEC[85] forced inflation to double-digit levels, averaging 11.3% in 1979 and 13.5% in 1980.[46]

Following a mid-1979 cabinet shake-up, Carter named Paul Volcker as Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board.[86] Volcker pursued a tight monetary policy to bring down inflation, but this policy also had the effect of slowing economic growth even further.[87] Carter enacted an austerity program by executive order, justifying these measures by observing that inflation had reached a "crisis stage"; both inflation and short-term interest rates reached 18 percent in February and March 1980.[88] In March, the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell to its lowest level since mid-1976, and the following month unemployment rose to seven percent.[89] The economy had entered a recession, and the difficult economic times continued as unemployment rose to 7.8 percent.[90] The economy experienced a V-shaped recession that coincided with Carter's re-election campaign, and it contributed to his unexpectedly severe loss.[91] GDP and employment totals regained pre-recession levels by the first quarter of 1981.[79][80]

Health care

During the 1976 presidential campaign, Carter proposed a health care reform plan that included key features of a bipartisan bill, sponsored by Senator Ted Kennedy, that provided for the establishment of a universal national health insurance (NHI) system.[92] Though most Americans had health insurance through Medicare, Medicaid, or private plans, approximately ten percent of the population did not have coverage in 1977. The establishment of an NHI plan was the top priority of organized labor and many liberal Democrats, but Carter had concerns about cost, as well as the inflationary impact, of such a system. He delayed consideration of health care through 1977, and ultimately decided that he would not support Kennedy's proposal to establish an NHI system that covered all Americans. Kennedy met repeatedly with Carter and White House staffers in an attempt to forge a compromise health care plan, but negotiations broke down in July 1978. Though Kennedy and Carter had previously been on good terms, differences over health insurance led to an open break between the two Democratic leaders.[93]

In June 1979, Carter proposed more limited health insurance reform—an employer mandate to provide private catastrophic health insurance. The plan would also extend Medicaid to the very poor without dependent minor children, and would add catastrophic coverage to Medicare.[94] Kennedy rejected the plan as insufficient.[95] In November 1979, Senator Russell B. Long led a bipartisan conservative majority of the Senate Finance Committee to support an employer mandate to provide catastrophic coverage and the addition of catastrophic coverage to Medicare.[94] These efforts were abandoned in 1980 due to budget constraints.[96]

Welfare and tax reform proposals

Carter sought a comprehensive overhaul of welfare programs in order to provide more cost-effective aid. Congress rejected almost all of his proposals.[97] Proposals contemplated by the Carter administration include a guaranteed minimum income, a federal job guarantee for the unemployed, a negative income tax, and direct cash payments to aid recipients. In early 1977, Secretary Califano presented Carter with several options for welfare reform, all of which Carter rejected because they increased government spending. In August 1977, Carter proposed a major jobs program for welfare recipients capable of working and a "decent income" to those who were incapable of working.[98] Carter was unable to win support for his welfare reform proposals, and they never received a vote in Congress.[99] In October 1978, Carter helped convince the Senate to pass the Humphrey–Hawkins Full Employment Act, which committed the federal government to the goals of low inflation and low unemployment. To the disappointment of the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) and organized labor, the final act did not include a provision authorizing the federal government to act as an employer of last resort in order to provide for full employment.[100]

Carter also sought tax reform in order to create a simpler, more progressive taxation system. He proposed taxing capital gains as ordinary income, eliminating tax shelters, limiting itemized tax deductions, and increasing the standard deduction.[101] Carter's taxation proposals were rejected by Congress, and no major tax reform bill was passed during Carter's presidency.[102] Carter did sign legislation known as the Social Security Amendments of 1977, which raised Social Security taxes and reduced Social Security benefits. The act corrected a technical error made in 1972 and ensured the short-term solvency of Social Security.[103]

Environment

Carter supported many of the goals of the environmentalist movement, and he signed several bills that were designed to protect the environment.[104] In 1977, Carter signed the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977, which regulates strip mining.[44] In 1980 Carter signed into law a bill that established Superfund, a federal program designed to clean up sites contaminated with hazardous substances.[105]

Cecil Andrus who had been governor of Idaho, served as secretary of the interior 1978-81. He convinced Carter to withdraw nearly half of 375 million acres of public domain land from commercial use in a series of executive moves and new laws. In December 1978 the president placed more 56 million acres of the state's Federal lands into the National Park system, protecting them from mineral or oil development The 1980 Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act, doubled the amount of public land set aside for national parks and wildlife refuges. Carter used his power under the 1906 Antiquities Act to set aside 57 million acres in 17 national monuments. The remaining acres were withdrawn under the 1976 Federal Land Policy and Management Act.[106] [107] Business and conservative interests complained that economic growth would be hurt.[108]

Education

Early into his term, Carter worked to fulfill a campaign promise to teachers' unions create a cabinet level education department. He hoped it would increase efficiency and equal opportunity, as well as enhance support for public schools. The unions hoped it would increase the flow of federal dollars to their schools. Opponents in both parties criticized it as an additional layer of bureaucracy that would reduce local control and local support of education.[109] In a February 28, 1978 address, Carter argued, "Education is far too important a matter to be scattered piecemeal among various government departments and agencies, which are often busy with sometimes dominant concerns."[110] In October 1979, Carter signed the Department of Education Organization Act. establishing the United States Department of Education. The first secretary was Shirley Mount Hufstedler, a liberal judge from California.[111] Carter also expanded the Head Start program with the addition of 43,000 children and families.[112] During his tenure, the percentage of nondefense dollars spent on education was doubled.[113]

Carter opposed tax breaks for Protestant schools in the South, which he decided were fighting integration. This action mobilized the Religious Right against him in 1980.[114] He also helped defeat the Moynihan-Packwood Bill. It called for tuition tax credits for parents to use for nonpublic school education. Carter believed the proposal was unconstitutional and too expensive.[115]

Other initiatives

Carter took a stance in support of decriminalization of cannabis, citing the legislation passed in Oregon in 1973.[116] In a 1977 address to Congress, Carter submitted that penalties for cannabis use should not outweigh the actual harms of cannabis consumption. Carter retained Nixon-era (yet pro-decriminalization) advisor Robert Du Pont, and appointed pro-decriminalization British physician Peter Bourne as his drug advisor (or "drug czar") to head up his newly formed Office of Drug Abuse Policy.[117][118] However, law enforcement, conservative politicians, and grassroots parents' groups opposed this measure. The net result of the Carter administration was the continuation of the War on Drugs and restrictions on cannabis,[117][119] while at the same time cannabis consumption in the United States reached historically high levels.[120]

Carter was the first president to address the topic of gay rights, and his administration was the first to meet with a group of gay rights activists.[121][122] Carter opposed the Briggs Initiative, a California ballot measure that would have banned gays and supporters of gay rights from being public school teachers.[122] Carter supported policy of affirmative action, and his administration submitted an amicus curiae brief to the Supreme Court while it heard the case of Regents of the Univ. of Cal. v. Bakke. The Supreme Court's holding, delivered in 1978, upheld the constitutionality of affirmative action but prohibited the use of racial quotas in college admissions.[123] First Lady Rosalynn Carter publicly campaigned for the ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment, and the president supported the extension of the ratification period for that amendment.[124]

Carter presided over the deregulation of several industries, which proponents hoped would help revive the sluggish economy. The Airline Deregulation Act abolished the Civil Aeronautics Board and granted airlines greater control over their operations. Carter also signed the Motor Carrier Act of 1980, which deregulated the trucking industry, and the Staggers Rail Act, which loosened regulations on railroads.[125]

The Housing and Community Development Act of 1977 set up Urban Development Action Grants, extended handicapped and elderly provisions, and established the Community Reinvestment Act,[126] which sought to prevent banks from denying credit and loans to poor communities.[127]

Foreign affairs

Brzezinski versus Vance

A key appointment was Zbigniew Brzezinski as National Security Advisor. He was a hard line Cold Warrior opposed to Communism and the USSR. Carter initially wanted to nominate George Ball to become Secretary of State, but he was vetoed by Brzezinski.[128] Vance negotiated the Panama Canal Treaties, along with peace talks in Rhodesia, Namibia and South Africa. He worked closely with Israeli Ministers Moshe Dayan and Ezer Weizman to secure the Camp David Accords in 1978. Vance was a strong advocate of disarmament. He insisted that the President make Paul Warnke Director of the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, over strong opposition by Senator Henry M. Jackson.[129][130]

Vance also pushed for detente with the Soviet Union, and clashed frequently with the hawkish Brzezinski. Vance tried to advance arms limitations by working on the SALT II agreement with the Soviet Union, which he saw as the central diplomatic issue of the time, but Brzezinski lobbied for a tougher more assertive policy vis-a-vis the Soviets. He argued for strong condemnation of Soviet activity in Africa and in the Third World as well as successfully lobbying for normalized relations with the People's Republic of China in 1978. As Brzezinski took control of the negotiations with Beijing, Vance was marginalized and his influence began to wane. When revolution erupted in Iran in late 1978, the two were divided on how to support the United States' ally the Shah of Iran. Vance argued in favor of reforms while Brzezinski urged him to crack down – the 'iron fist' approach. Unable to receive a direct course of action from Carter, the mixed messages that the shah received from Vance and Brzezinski contributed to his confusion and indecision as he fled Iran in January 1979 and his regime collapsed.[131]

Improved relations with Canada

Relations deteriorated on many points in the Nixon years (1969-74), including trade disputes, defense agreements, energy, fishing, the environment, cultural imperialism, and foreign policy. They changed for the better when Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and Carter found a better rapport. The late 1970s saw a more sympathetic American attitude toward Canadian political and economic needs, the pardoning of draft evaders who had moved to Canada, and the passing of old matters such as Watergate and the Vietnam War. Canada more than ever welcomed American investments during "the stagflation" that hurt both nations.[132]

Defense policy

Carter, a graduate of the Naval Academy, had been trained on nuclear submarines. He took a close interest in defense policy, especially new technologies, after naming nuclear physicist Harold Brown as Secretary of Defense. Although his campaign platform in 1976 called for a reduction in defense spending, Carter called for a 3% increase in the defense budget. He sought a sturdier defense posture by stationing medium range nuclear missiles in Europe aimed at the Soviet Union.[133] Carter and Brown worked to keep the balance with the Soviets in strategic weapons by improving land-based ICBMs, by equipping strategic bombers with cruise missiles and by deploying far more submarine-launched missiles tipped with MIRVs, or multiple warheads that could hit multiple targets. They continued development of the MX missile and modernization of NATO's Long-Range Theater Nuclear Force.[134][135]

NATO and USSR on IRBM issue

In March 1976, the Soviet Union first deployed the SS-20 Saber (also known as the RSD-10) in its European territories, a mobile, concealable intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) with a multiple independently targetable reentry vehicle (MIRV) containing three nuclear 150-kiloton warheads.[136] The SS-20's range of 4,700–5,000 kilometers (2,900–3,100 mi) was great enough to reach Western Europe from well within Soviet territory; the range was just below the SALT II minimum range for an intercontinental ballistic missile, 5,500 km (3,400 mi).[137][138][139]

The SS-20 replaced aging Soviet systems of the SS-4 Sandal and SS-5 Skean, which were seen to pose a limited threat to Western Europe due to their poor accuracy, limited payload (one warhead), lengthy preparation time, difficulty in being concealed, and immobility (thus exposing them to pre-emptive NATO strikes ahead of a planned attack).[140] Whereas the SS-4 and SS-5 were seen as defensive weapons, the SS-20 was seen as a potential offensive system.[141]

Washington initially considered its strategic nuclear weapons and nuclear-capable aircraft to be adequate counters to the SS-20 and a sufficient deterrent against Soviet aggression. In 1977, however, Chancellor Helmut Schmidt of West Germany argued in a speech that a Western response to the SS-20 deployment should be explored, a call which was echoed by NATO, given a perceived Western disadvantage in European nuclear forces.[142] Schmidt's speech pressured the US into developing a response.[143]

On 12 December 1979, following European pressure for a response to the SS-20, Western foreign and defense ministers made the NATO Double-Track Decision.[144]They argued that the Warsaw Pact had "developed a large and growing capability in nuclear systems that directly threaten Western Europe": "theater" nuclear systems (i.e., tactical nuclear weapons.[145] In describing this "aggravated" situation, the ministers made direct reference to the SS-20 featuring "significant improvements over previous systems in providing greater accuracy, more mobility, and greater range, as well as having multiple warheads". The ministers also attributed the altered situation to the deployment of the Soviet Tupolev Tu-22M strategic bomber, which they believed to display "much greater performance" than its predecessors. Furthermore, the ministers expressed concern that the Soviet Union had gained an advantage over NATO in "Long-Range Theater Nuclear Forces" (LRTNF), and also significantly increased short-range theater nuclear capacity. To address these developments, the ministers adopted two policy "tracks". One thousand theater nuclear warheads, out of 7,400 such warheads, would be removed from Europe and the US would pursue bilateral negotiations with the Soviet Union intended to limit theater nuclear forces. Should these negotiations fail, NATO would modernize its own LRTNF, or intermediate-range nuclear forces (INF), by replacing US Pershing 1a missiles with 108 Pershing II launchers in West Germany and deploying 464 BGM-109G Ground Launched Cruise Missiles (GLCMs) to Belgium, Italy, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom beginning in December 1983.[138][146][147][148]

Cold War

Carter took office during the Cold War, a sustained period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, relations between the two superpowers had improved through a policy known as detente. In a reflection of the waning importance of the Cold War, some of Carter's contemporaries labeled him as the first post-Cold War president, but relations with the Soviet Union would continue to be an important factor in American foreign policy in the late 1970s and the 1980s. Many of the leading officials in the Carter administration, including Carter himself, were members of the Trilateral Commission, which de-emphasized the Cold War. The Trilateral Commission instead advocated a foreign policy focused on aid to Third World countries and improved relations with Western Europe and Japan. The central tension of the Carter administration's foreign policy was reflected in the division between Secretary of State Cyrus Vance, who sought improved relations with the Soviet Union and the Third World, and National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski, who favored confrontation with the Soviet Union on a range of issues.[149]

Human rights

Carter believed that previous administrations had erred in allowing the Cold War concerns and Realpolitik to dominate foreign policy. His administration placed a new emphasis on human rights, democratic values, nuclear proliferation, and global poverty.[150] The Carter administration's human rights emphasis was part of a broader, worldwide focus on human rights in the 1970s, as non-governmental organizations such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch became increasingly prominent. Carter nominated civil rights activist Patricia M. Derian as Coordinator for Human Rights and Humanitarian Affairs, and in August 1977, had the post elevated to that of Assistant Secretary of State. Derian established the United States' Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, published annually since 1977.[151] Latin America was central to Carter's new focus on human rights.[152] The Carter administration ended support to the historically U.S.-backed Somoza regime in Nicaragua and directed aid to the new Sandinista National Liberation Front government that assumed power after Somoza's overthrow. Carter also cut back or terminated military aid to Augusto Pinochet of Chile, Ernesto Geisel of Brazil, and Jorge Rafael Videla of Argentina, all of whom he criticized for human rights violations.[153]

Carter's ambassador to the United Nations, Andrew Young, was the first African-American to hold a high-level diplomatic post. Along with Carter, he sought to change U.S. policy towards Africa, emphasizing human rights concerns over Cold War issues.[154] In 1978, Carter became the first sitting president to make an official state visit to Sub-Saharan Africa,[155] a reflection of the region's new importance under the Carter administration's foreign policy.[156] Unlike his predecessors, Carter took a strong stance against white minority rule in Rhodesia and South Africa. With Carter's support, the United Nations passed Resolution 418, which placed an arms embargo on South Africa. Carter won the repeal of the Byrd Amendment, which had undercut international sanctions on the Rhodesian government of Ian Smith. He also pressured Smith to hold elections, leading to the 1979 Rhodesia elections and the eventual creation of Zimbabwe.[157]

The more assertive human rights policy championed by Derian and State Department Policy Planning Director Anthony Lake was blunted by the opposition of Brzezinski. These policy disputes reached their most contentious point during the 1979 fall of Pol Pot's genocidal regime of Democratic Kampuchea following the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia, when Brzezinski prevailed in having the administration refuse to recognize the new Cambodian government due to its support by the Soviet Union.[158] Despite human rights concerns, Carter continued U.S. support for Joseph Mobutu of Zaire, who defeated Angolan-backed insurgents in conflicts known as Shaba I and Shaba II.[159] His administration also generally refrained from criticizing human rights abuses in the Philippines, Indonesia, South Korea, Iran, Israel, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and North Yemen.[160][161]

SALT II

Ford and Nixon had sought to reach agreement on a second round of the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT), which had set upper limits on the number of nuclear weapons possessed by both the United States and the Soviet Union. Carter hoped to extend these talks by reaching an agreement to reduce, rather than merely set upper limits on, the nuclear arsenals of both countries.[162] At the same time, he criticized the Soviet Union's record with regard to human rights, partly because he believed the public would not support negotiations with the Soviets if the president seemed too willing to accommodate the Soviets.[163] Carter and Soviet Leader Leonid Brezhnev reached an agreement in June 1979 in the form of SALT II, but Carter's waning popularity and the opposition of Republicans and neoconservative Democrats made ratification difficult.[163] The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan ended detente and reopened the Cold War, while ending talk of ratifying SALT II.[164]

Afghanistan

Afghanistan had been non-aligned during the early stages of the Cold War, but a 1973 coup had brought a pro-Western government into power.[165] Five years later, Communists under the leadership of Nur Muhammad Taraki seized power.[166] The new regime—which was divided between Taraki's extremist Khalq faction and the more moderate Parcham—signed a treaty of friendship with the Soviet Union in December 1978.[166][167] Taraki's efforts to improve secular education and redistribute land were accompanied by mass executions and political oppression unprecedented in Afghan history, igniting a revolt by mujahideen rebels.[166] Following a general uprising in April 1979, Taraki was deposed by Khalq rival Hafizullah Amin in September.[166][167] Soviet leaders feared that an Islamist government in Afghanistan would threaten the control of Soviet Central Asia, and, as the unrest continued, they deployed 30,000 soldiers to the Soviet–Afghan border.[168] Carter and Brzezinski both saw Afghanistan as a potential "trap" that could expend Soviet resources in a fruitless war, and the U.S. began sending aid to the mujahideen rebels in early 1979.[169] By December, Amin's government had lost control of much of the country, prompting the Soviet Union to invade Afghanistan, execute Amin, and install Parcham leader Babrak Karmal as president.[166][167]

Carter was surprised by the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, as the consensus of the U.S. intelligence community during 1978 and 1979 was that Moscow would not forcefully intervene.[170] CIA officials had tracked the deployment of Soviet soldiers to the Afghan border, but they had not expected the Soviets to launch a full-fledged invasion.[171] Carter believed that the Soviet conquest of Afghanistan would present a grave threat to the Persian Gulf region, and he vigorously responded to what he considered a dangerous provocation.[172] In a televised speech, Carter announced sanctions on the Soviet Union, promised renewed aid to Pakistan, and articulated the Carter doctrine, which stated that the U.S. would repel any attempt to gain control of the Persian Gulf.[173][174] Pakistani leader Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq had previously had poor relations with Carter due to Pakistan's nuclear program and the execution of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, but the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and instability in Iran reinvigorated the traditional Pakistan–United States alliance.[170] In cooperation with Saudi Arabia and Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), Carter increased aid to the mujahideen through the CIA's Operation Cyclone.[174] Carter also later announced a U.S. boycott of the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow.[175]

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan brought a significant change in Carter's foreign policy and ended the period of detente that had begun in the mid-1960s. Returning to a policy of containment, the United States reconciled with Cold War allies and increased the defense budget, leading to a new arms race with the Soviet Union.[176] U.S. support for the mujahideen would accelerate under Carter's successor, Ronald Reagan, at a final cost to U.S. taxpayers of some $3 billion. The Soviets were unable to quell the insurgency and withdrew from Afghanistan in 1989, precipitating the dissolution of the Soviet Union itself.[170]

To punish Moscow, Carter imposed an embargo on shipping American wheat. This hurt American farmers more than it did the Soviet economy, and Reagan resumed sales. Other nations sold their own grain to the USSR, and the Soviets had ample reserve stocks and a good harvest of their own.[177]

Middle East

Historian Jørgen Jensehaugen argues that by the time Carter left office in January 1981, he:

- was in an odd position—he had attempted to break with traditional US policy but ended up fulfilling the goals of that tradition, which had been to break up the Arab alliance, side-line the Palestinians, build an alliance with Egypt, weaken the Soviet Union and secure Israel.[178]

Camp David Accords

On taking office, Carter decided to use his influence to mediate the long-running Arab–Israeli conflict.[179] Carter sought a comprehensive settlement between Israel and its neighbors through a reconvening of the 1973 Geneva Conference, but these efforts had collapsed by the end of 1977.[180] Though unsuccessful in reconvening the conference, Carter convinced Egyptian leader Anwar Sadat to visit Israel in 1978. Sadat's visit drew the condemnation of other Arab League countries, but Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin each expressed an openness to bilateral talks. Begin sought security guarantees; Sadat sought the withdrawal of Israeli forces from the Sinai Peninsula and home rule for the West Bank and Gaza, Israeli-occupied territories that were largely populated by Palestinian Arabs. Israel had taken control of the West Bank and Gaza in the 1967 Six-Day War, while the Sinai had been occupied by Israel since the end of the 1973 Yom Kippur War.[181]

Seeking to further negotiations, Carter invited Begin and Sadat to the presidential retreat of Camp David in September 1978. Because direct negotiations between Sadat and Begin proved unproductive, Carter began meeting with the two leaders individually.[182] While Begin was willing to withdraw from the Sinai Peninsula, he refused to agree to the establishment of a Palestinian state. Israel had begun constructing settlements in the West Bank, which emerged as an important barrier to a peace agreement. Unable to come to definitive settlement over an Israeli withdrawal, the two sides reached an agreement in which Israel made vague promises to allow the creation of an elected government in the West Bank and Gaza. In return, Egypt became the first Arab state to recognize Israel's right to exist. The Camp David Accords were the subject of intense domestic opposition in both Egypt and Israel, as well as the wider Arab World, but each side agreed to negotiate a peace treaty on the basis of the accords.[183]

On March 26, 1979, Egypt and Israel signed a peace treaty in Washington, D.C.[184] Carter's role in getting the treaty was essential. Aaron David Miller interviewed many officials for his book The Much Too Promised Land (2008) and concluded the following: "No matter whom I spoke to — Americans, Egyptians, or Israelis — most everyone said the same thing: no Carter, no peace treaty."[185] Carter himself viewed the agreement as his most important accomplishment in office.[183]

Iranian Revolution and hostage crisis

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the Shah of Iran, had been a reliable U.S. ally since the 1953 Iranian coup d'état. During the years after the coup, the U.S. lavished aid on Iran, while Iran served as a dependable source of oil exports.[186] Carter, Vance, and Brzezinski all viewed Iran as a key Cold War ally, not only for the oil it produced but also because of its influence in OPEC and its strategic position between the Soviet Union and the Persian Gulf.[187] Despite human rights violations, Carter visited Iran in late 1977 and authorized the sale of U.S. fighter aircraft. That same year, rioting broke out in several cities, and it soon spread across the country. Poor economic conditions, the unpopularity of Pahlavi's "White Revolution", and an Islamic revival all led to increasing anger among Iranians, many of whom also despised the United States for its support of Pahlavi and its role in the 1953 coup.[186]

Washington's new demands for human rights angered the Shah, and split the Carter administration. Vance and the State Department made it a high priority, while Brzezinski warned that it would undermine the strength of America's most important ally in the region. The State Department's Bureau of Human Rights took an activist approach, under the leadership of the outspoken Patricia Derian. Carter did allow the sale of riot control equipment to suppress increasingly vocal and violent protests, especially from the religious element.[188][189]

By 1978, the Iranian Revolution had broken out against the Shah's rule.[190] Secretary of State Vance argued that the Shah should institute a series of reforms to appease the voices of discontent, while Brzezinski argued in favor of a crackdown on dissent. The mixed messages that the Shah received from Vance and Brzezinski contributed to his confusion and indecision. The Shah went into exile, leaving a caretaker government in control. A popular religious figure, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, returned from exile in February 1979 to popular acclaim. As the unrest continued, Carter allowed Pahlavi into the United States for medical treatment.[191] Carter and Vance were both initially reluctant to admit Pahlavi due to concerns about the reaction in Iran, but Iranian leaders assured them that it would not cause an issue.[192] In November 1979, shortly after Pahlavi was allowed to enter the U.S., a group of Iranians stormed the U.S. embassy in Tehran and took 66 American captives, beginning the Iran hostage crisis.[191] Iranian Prime Minister Mehdi Bazargan ordered the militants to release the hostages, but he resigned from office after Khomeini backed the militants.[192]

The crisis quickly became the subject of international and domestic attention, and Carter vowed to secure the release of the hostages. He refused the Iranian demand of the return of Pahlavi in exchange for the release of the hostages. His approval ratings rose as Americans rallied around his response, but the crisis became increasingly problematic for his administration as it continued.[193] In an attempt to rescue the hostages, Carter launched Operation Eagle Claw in April 1980. The operation was a total disaster, and it ended in the death of eight American soldiers. The failure of the operation strengthened Ayatollah Khomenei's position in Iran and badly damaged Carter's domestic standing.[194] Carter was dealt another blow when Vance, who had consistently opposed the operation, resigned.[195] Iran refused to negotiate the return of the hostages until Iraq launched an invasion in September 1980 With Algeria serving as an intermediary, negotiations continued until an agreement was reached in January 1981. In return for releasing the 52 captives, Iran accepted over $7 billion in monetary compensation and the unfreezing of Iranian assets in the United States. Iran waited to release the captives until hours after Carter left office on January 20, 1981.[196]

Latin America

Turning over the canal to Panama

Since the 1960s, Panama had called for turning over to it the Panama Canal.[197] The bipartisan national policy of turning over the Canal to Panama had been established by presidents Johnson Nixon and Ford, but negotiations had dragged on for a dozen years. Carter made it a priority, hoping to launch his foreign policy with a dramatic success. Another postponement might precipitate violent upheaval in Panama, in which the canal could be damaged or blocked. Furthermore, a settlement would win approval across Latin America as a gracious apology for American wrongdoing. It would implement Carter's call for a moral cleaning of American foreign policy.[198] His administration negotiated the Torrijos-Carter Treaties, two treaties which provided that Panama would gain control of the canal in 1999.

Carter's initiative faced intense opposition from conservatives, led by Reagan, who charged that Carter was giving away for free a crucial and costly American asset. The attack was mobilized by numerous groups, especially the American Conservative Union, the Conservative Caucus, the Committee for the Survival of a Free Congress, Citizens for the Republic, the American Security Council, the Young Republicans, the National Conservative Political Action Committee, the Council for National Defense, Young Americans for Freedom, the Council for Inter-American Security, and the Campus Republican Action Organization.[199] Altogether, twenty organizations coordinated their attacks using two umbrella groups: the Committee to Save the Panama Canal and the Emergency Coalition to Save the Panama Canal. This enabled the opposition to plan strategy and coordinate tactics while dividing tasks, sharing new information and pooling resources. In contrast, the supporters were not coordinated.[200]

During its ratification debate, the Senate added amendments that granted the U.S. the right to intervene militarily to keep the canal open, which the Panamanians assented to after further negotiations.[201] In March 1978, the Senate ratified both treaties by a margin of 68-to-32. The Canal Zone and all its facilities were turned over to Panama on 31 December 1999, and Reagan repeatedly attacked Carter on this issue in the 1980 presidential campaign.[202][203]

Cuba

Carter hoped to improve relations with Cuba upon taking office, but any thaw in relations was prevented by ongoing Cold War disputes in Central America and Africa. In early 1980, Cuban leader Fidel Castro announced that anyone who wished to leave Cuba would be allowed to do so through the port of Mariel. After Carter announced that the United States would provide "open arms for the tens of thousands of refugees seeking freedom from Communist domination", Cuban Americans arranged the Mariel boatlift. The Refugee Act, signed earlier in the year, had provided for annual cap of 19,500 Cuban immigrants to the United States per year, and required that those refugees go through a review process. By September, 125,000 Cubans had arrived in the United States, and many faced a lack of inadequate food and housing. Carter was widely criticized for his handling of the boatlift, especially in the electorally important state of Florida.[204]

Asia and Africa

Rapprochement with China

Continuing a rapprochement begun during the Nixon administration, Carter sought closer relations with the People's Republic of China (PRC). The two countries increasingly collaborated against the Soviet Union, and the Carter administration tacitly consented to the Chinese invasion of Vietnam. In 1979, Carter extended formal diplomatic recognition to the PRC for the first time. This decision led to a boom in trade between the United States and the PRC, which was pursuing economic reforms under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping.[205] After the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, Carter allowed the sale of military supplies to China and began negotiations to share military intelligence.[206] In January 1980, Carter unilaterally revoked the Sino-American Mutual Defense Treaty with the Republic of China (ROC), which had lost control of mainland China to the PRC in the Chinese Civil War, but retained control the island of Taiwan. Carter's abrogation of the treaty was challenged in court by conservative Republicans, but the Supreme Court ruled that the issue was a non-justiciable political question in Goldwater v. Carter. The U.S. continued to maintain diplomatic contacts with the ROC through the 1979 Taiwan Relations Act.[207]

South Korea

One of Carter's first acts was to order the withdrawal of troops from South Korea, which had hosted a large number of U.S. military personnel since the end of the Korean War. Carter believed that the soldiers could be put to better use in Western Europe, but opponents of the withdrawal feared that North Korea would invade South Korea in the aftermath of the withdrawal. South Korea and Japan both protested the move, as did many members of Congress, the military, and the State Department. After a strong backlash, Carter delayed the withdrawal, and ultimately only a fraction of the U.S. forces left South Korea. Carter's attempt to remove U.S. forces from South Korea weakened the government of South Korean President Park Chung-hee, who was assassinated in 1979.[208]

Africa

Until 1975, Washington ignored southern Africa because the Cold War was not in play there. Weak insurgencies existed in Angola, Mozambique, Rhodesia, and Namibia, but did not appear to threaten white rule after the colonial powers left. The collapse of the last colonial power, Portuguese, in April 1974 meant the end of white rule in Angola and Mozambique. Cuba, with Soviet help, sent a large military force. It took control of Angola in 1976. The region now became a Cold War battleground. The Carter administration negotiated endlessly with South Africa and the South West Africa People’s Organization (SWAPO), which was the guerrilla movement fighting for the independence of Namibia from South Africa. Vance and Brzezinski battled over policy but the U.S. never sent troops. Instead Cuba and the Soviet Union strongly supported the Namibian insurgents and 20,000 Cuban soldiers were poised in neighboring Angola. Thy Carter team failed to find a solution, [209][210]

In sharp contrast to Nixon and Ford, Carter gave priority to sub-Sahara Africa.[211][212] The chief policy person was Andrew Young, a leader in the black Atlanta community who became Ambassador to the United Nations. Young opened up friendly relationships with key leaders, especially in Nigeria. A highly controversial issue was independence of Namibia from Union of South Africa. Young began United Nations discussions which went nowhere. Only after the Cold War ended in 1990 did Namibia become independent. [213] Vice President Mondale condemned the South African system of apartheid. Young advocated strong sanctions after the murder by South African police of Steve Biko in 1977. Carter refused and only imposed a limited arms embargo and South Africa ignored the protests.[214]

When Somalia invaded Ethiopia in July 1977 in the Ogaden War, the Cold War played a role. The Soviets, who traditionally backed Somalia, now switched to support of the Marxist regime in Ethiopia. The United States remained neutral because Somalia was clearly the aggressor nation, and in 1978 with the assistance of 20,000 Cuban troops, Ethiopia defeated Somalia. The most important American success was helping the transition from white-dominated Southern Rhodesia to black rule in Zimbabwe. The United States supported UN resolutions and sanctions that proved effective in April 1980.[215][216] Despite human rights concerns, Carter continued U.S. support for Joseph Mobutu of Zaire, who defeated Angolan-backed insurgents in conflicts known as Shaba I and Shaba II.

Historians are generally agreed that the Presidency of Jimmy Carter was not very successful when it came to Africa. However, there are multiple explanations available.[217] The orthodox interpretation posits Carter as a dreamy star-eyed idealist. Revisionists said that did not matter nearly as much as the intense rivalry between dovish Secretary of State Cyrus Vance and hawkish National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski. Vance lost nearly all the battles, and finally resigned in disgust. [218] Meanwhile there are now post-revisionist historians who blame his failures on his confused management style and his refusal to make tough decisions.[219] Along post-revisionist lines, Nancy Mitchell in a monumental book depicts Carter as a decisive but ineffective Cold Warrior, who, nevertheless had some successes because Soviet incompetence was even worse.[220]

List of international trips

Carter made 12 international trips to 25 nations during his presidency.[221]

| Dates | Country | Locations | Details | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | May 5–11, 1977 | London, Newcastle |

Attended the 3rd G7 summit. Also met with the prime ministers of Greece, Belgium, Turkey, Norway, the Netherlands and Luxembourg, and with the President of Portugal. Addressed NATO Ministers meeting. | |

| May 9, 1977 | Geneva | Official visit. Met with President Kurt Furgler. Also met with Syrian President Hafez al-Assad. | ||

| 2 | December 29–31, 1977 | Warsaw | Official visit. Met with First Secretary Edward Gierek. | |

| December 31, 1977 – January 1, 1978 | Tehran | Official visit. Met with Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and King Hussein of Jordan. | ||

| January 1–3, 1978 | New Delhi, Daulatpur Nasirabad[222] | Met with President Neelam Sanjiva Reddy and Prime Minister Morarji Desai. Addressed Parliament of India. | ||

| January 3–4, 1978 | Riyadh | Met with King Khalid and Crown Prince Fahd. | ||

| January 4, 1978 | Aswan | Met with President Anwar Sadat and German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt. | ||

| January 4–6, 1978 | Paris, Normandy, Bayeux, Versailles |

Met with President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing and Prime Minister Raymond Barre. | ||

| January 6, 1978 | Brussels | Met with King Baudouin and Prime Minister Leo Tindemans. Attended meetings of the Commission of the European Communities and the North Atlantic Council. | ||

| 3 | March 28–29, 1978 | Caracas | Met with President Carlos Andrés Pérez. Addressed Congress and signed maritime boundary agreement. | |

| March 29–31, 1978 | Brasília Rio de Janeiro |

Official visit. Met with President Ernesto Geisel and addressed National Congress. | ||

| March 31 – April 3, 1978 | Lagos | State visit. Met with President Olusegun Obasanjo. | ||

| April 3, 1978 | Monrovia | Met with President William R. Tolbert, Jr. | ||

| 4 | June 16–17, 1978 | Panama City | Invited by President Demetrio B. Lakas and General Omar Torrijos to sign protocol confirming exchange of documents ratifying Panama Canal treaties. Also met informally with Venezuelan President Carlos Andrés Pérez, Colombian President Alfonso López Michelsen, Mexican President José López Portillo, Costa Rican Rodrigo Carazo Odio and Jamaican Prime Minister Michael Manley of Jamaica. | |

| 5 | July 14–15, 1978 | Bonn, Wiesbaden-Erbenheim, Frankfurt |

State visit. Met with President Walter Scheel and Chancellor Helmut Schmidt. Addressed U.S. and German military personnel. | |

| July 15, 1978 | West Berlin | Spoke at the Berlin Airlift Memorial. | ||

| July 16–17, 1978 | Bonn | Attended the 4th G7 summit. | ||

| 6 | January 4–9, 1979 | Basse-Terre, Guadeloupe | Met informally with President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt and British Prime Minister James Callaghan. | |

| 7 | February 14–16, 1979 | Mexico City | State visit. Met with President José López Portillo. Addressed the Mexican Congress. | |

| 8 | March 7–9, 1979 | Cairo, Alexandria, Giza |

State visit. Met with President Anwar Sadat. Addressed People's Assembly of Egypt. | |

| March 10–13, 1979 | Tel Aviv, Jerusalem |

State visit. Met with President Yitzhak Navon and Prime Minister Menachem Begin. Addressed the Knesset. | ||

| March 13, 1979 | Cairo | Met with President Anwar Sadat. | ||

| 9 | June 14–18, 1979 | Vienna | State visit. Met with President Rudolf Kirchschläger and Chancellor Bruno Kreisky. Met with Soviet General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev to sign SALT II Treaty. | |

| 10 | June 25–29, 1979 | Tokyo, Shimoda |

Attended the 5th G7 summit. State visit. Met with Emperor Hirohito and Prime Minister Masayoshi Ōhira. | |

| June 29 – July 1, 1979 | Seoul | State visit. Met with President Park Chung-hee and Prime Minister Choi Kyu-hah. | ||

| 11 | June 19–24, 1980 | Rome, Venice |

Attended the 6th G7 summit. State Visit. Met with President Sandro Pertini. | |

| June 21, 1980 | Apostolic Palace | Audience with Pope John Paul II. | ||

| June 24–25, 1980 | Belgrade | Official visit. Met with President Cvijetin Mijatović. | ||

| June 25–26, 1980 | Madrid | Official visit. Met with King Juan Carlos I and Prime Minister Adolfo Suárez. | ||

| June 26–30, 1980 | Lisbon | Official visit. Met with President António Ramalho Eanes and Prime Minister Francisco de Sá Carneiro. | ||

| 12 | July 9–10, 1980 | Tokyo | Official visit. Attended memorial services for former Prime Minister Masayoshi Ōhira. Met with Emperor Hirohito, Bangla President Ziaur Rahman, Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser, Thai Prime Minister Prem Tinsulanonda and Chinese Premier Hua Guofeng. |

Controversies

OMB Director Bert Lance resigned his position on September 21, 1977, amid allegations of improper banking activities prior to his becoming director.[223] The controversy over Lance damaged Carter's standing with Congress and the public, and Lance's resignation removed one of Carter's most effective advisers from office.[224] In April 1979, Attorney General Bell appointed Paul J. Curran as a special counsel to investigate loans made to the peanut business owned by Carter by a bank controlled by Bert Lance. Unlike Archibald Cox and Leon Jaworski who were named as special prosecutors to investigate the Watergate scandal, Curran's position as special counsel meant that he would not be able to file charges on his own, but would require the approval of Assistant Attorney General Philip Heymann.[225] Carter became the first sitting president to testify under oath as part of an investigation of that president.[226] The investigation was concluded in October 1979, with Curran announcing that no evidence had been found to support allegations that funds loaned from the National Bank of Georgia had been diverted to Carter's 1976 presidential campaign.[227]

Carter's brother Billy generated a great deal of notoriety during Carter's presidency for his colorful and often outlandish public behavior.[228] The Senate began an investigation into Billy Carter's activities after it was disclosed that Libya had given Billy over $200,000 for unclear reasons.[44] The controversy over Billy Carter's relation to Libya became known as "Billygate", and, while the president had no personal involvement in it, Billygate nonetheless damaged the Carter administration.[229]

1980 presidential election