Interwar France: Difference between revisions

→Expatriate culture: copy ex "Non-conformists of the 1930s" |

→Non-conformists of the 1930s: copy ex "Non-conformists of the 1930s" |

||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

{{Main|Non-conformists of the 1930s}} |

{{Main|Non-conformists of the 1930s}} |

||

The "[[non-conformists of the 1930s]]'' were intellectuals seeking new solutions to face the political, economic and social crisis. The name was coined in 1969 by the historian Jean-Louis Loubet del Bayle to describe a movement which revolved around [[Emmanuel Mounier]]'s [[personalism]]. They attempted to find a "third ([[communitarian]]) alternative" between [[socialism]] and [[capitalism]], and opposed both [[liberalism]]/[[parliamentarism]]/[[democracy]] and [[fascism]].<ref name=EHESS>[http://www.ehess.fr/centres/ceifr/assr/N118/78.htm Account of Jean-Louis Loubet del Bayle]'s book in the [[Archives de Sciences Sociales des Religions]] n°118, on the [[EHESS]] website {{fr icon}}</ref><ref name="Hellman2002">{{cite book|author=John Hellman|title=Communitarian Third Way: Alexandre Marc and Ordre Nouveau, 1930-2000|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FktLgT8B2yQC|date=2002|page=13|publisher=McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP|isbn=978-0-7735-2376-0}}</ref> |

The "[[non-conformists of the 1930s]]'' were intellectuals seeking new solutions to face the political, economic and social crisis. The name was coined in 1969 by the historian Jean-Louis Loubet del Bayle to describe a movement which revolved around [[Emmanuel Mounier]]'s [[personalism]]. They attempted to find a "third ([[communitarian]]) alternative" between [[socialism]] and [[capitalism]], and opposed both [[liberalism]]/[[parliamentarism]]/[[democracy]] and [[fascism]].<ref name=EHESS>[http://www.ehess.fr/centres/ceifr/assr/N118/78.htm Account of Jean-Louis Loubet del Bayle]'s book in the [[Archives de Sciences Sociales des Religions]] n°118, on the [[EHESS]] website {{fr icon}}</ref><ref name="Hellman2002">{{cite book|author=John Hellman|title=Communitarian Third Way: Alexandre Marc and Ordre Nouveau, 1930-2000|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FktLgT8B2yQC|date=2002|page=13|publisher=McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP|isbn=978-0-7735-2376-0}}</ref> |

||

Three main currents of non-conformists may be distinguished: |

|||

*The review ''[[Esprit (magazine)|Esprit]]'', founded in 1931 by [[Emmanuel Mounier]] and which was the main mouthpiece of personalism. |

|||

*The ''[[Ordre nouveau (personalism)|Ordre nouveau]]'' (New Order) group, created by [[Alexandre Marc]] and influenced by [[Robert Aron]] and [[Arnaud Dandieu]]'s works. [[Charles de Gaulle]] would have some contacts with them between the end of 1934 and the beginning of 1935.<ref name=EHESS/> [[Jean Coutrot]], who became during the [[Popular Front (France)|Popular Front]] vice-president of the Committee of Scientific Organisation of Labour of the Minister [[Charles Spinasse]], participated in the technical reunions of ''Ordre nouveau''.<ref>[http://centre-histoire.sciences-po.fr/archives/fonds/jean_coutrot.html Biographical notice] of [[Jean Coutrot]], ''Centre d'histoire de [[Sciences Po]]'' {{fr icon}}</ref> |

|||

*The ''[[Jeune Droite]]'' (Young Right — a term coined by Mounier) that gathered young [[intellectual]]s who had more or less broken with the monarchist ''[[Action Française]]'', including [[Jean de Fabrègues]], [[Jean-Pierre Maxence]], [[Thierry Maulnier]], [[Maurice Blanchot]], as well as the journals ''[[Les Cahiers]]'', ''[[Réaction pour l'ordre]]'', ''[[La Revue française]]'' or ''[[La Revue du Siècle]]''. |

|||

These young intellectuals (most were about 25 years old) all considered that France was confronted by a "[[civilisation]] crisis" and opposed, despite their differences, what Mounier called the "established disorder" (''le désordre établi''). The latter was represented by [[capitalism]], [[individualism]], [[economic liberalism]] and [[materialism]]. Opposed both to [[Fascism]] and to [[Communism]] (qualified for the first as a "false Fascist-[[spiritualism]] <ref name=Slama>[http://www.supportscoursenligne.sciences-po.fr/2006_2007/ag_slama/seance_10.pdf Prospectus de présentation de la revue "Esprit"] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070929122012/http://www.supportscoursenligne.sciences-po.fr/2006_2007/ag_slama/seance_10.pdf |date=2007-09-29 }}, presented by [[Alain-Gérard Slama]], on-line course of [[Sciences Po]], 18 May 2007 {{fr icon}}</ref>" and for the latter as plain materialism), they aimed at creating the conditions of a "spiritual revolution" which would simultaneously transform Man and things. They called for a "New Order", beyond individualism and [[collectivism]], oriented towards a "[[federalist]]," "communautary and personalist" organisation of social relations. |

|||

The Non-Conformists were influenced both by French [[socialism]], in particular by [[Proudhonism]] (an important influence of ''Ordre nouveau'') and by [[Social Catholicism]], which permeated ''Esprit'' and the ''Jeune Droite''. They inherited from both currents a form of scepticism towards politics, which explains some [[anti-statism]] stances, and renewed interest in social and economical transformations.<ref>Jean-Louis Loubet del Bayle, [http://www.revuejibrile.com/JIBRILE/PDF/JEANLOUISLOUBETDELBAYLE.pdf A 2001 Interview] (p.3) in the ''Revue Jibrile'' {{fr icon}}</ref> Foreign influences were more restricted, and were limited to the discovery of the "precursors of [[existentialism]]" ([[Kierkegaard]], [[Nietzsche]], [[Heidegger]], [[Max Scheler]]) and contacts between ''Ordre nouveau'' and several members of the German [[Conservative Revolutionary movement]].<ref name="A 2001 Interview">Jean-Louis Loubet del Bayle, [http://www.revuejibrile.com/JIBRILE/PDF/JEANLOUISLOUBETDELBAYLE.pdf A 2001 Interview] (p.4) in the ''Revue Jibrile'' {{fr icon}}</ref> They were in favor of [[decentralization]], underscored the importance of intermediary bodies, and opposed [[finance capitalism]].<ref name="A 2001 Interview"/> |

|||

The movement was close to [[liberalism]] in the attention given to [[civil society]] and in its distrust of the state; but it also criticized liberal individualism and its negligence of "intermediate bodies" (family, village, etc.<ref>Jean-Louis Loubet del Bayle, [http://www.revuejibrile.com/JIBRILE/PDF/JEANLOUISLOUBETDELBAYLE.pdf A 2001 Interview] (p.5) in the ''Revue Jibrile'' {{fr icon}}</ref> — the reactionary writer [[Maurice Barrès]] also insisted on the latter). They were characterized by the will to find a "[[Third Way]]" between Socialism and Capitalism, individualism and collectivism, [[idealism]] and materialism and the [[Left–right politics|left–right distinction in politics]].<ref>Jean-Louis Loubet del Bayle, [http://www.revuejibrile.com/JIBRILE/PDF/JEANLOUISLOUBETDELBAYLE.pdf A 2001 Interview] (p.6) in the ''Revue Jibrile'' {{fr icon}}</ref> |

|||

After the [[February 6, 1934 riots]] organized by [[far-right leagues]], the Non-Conformists split toward various directions. [[Bertrand de Jouvenel]] made the link between the Non-Conformists and the supporters of ''[[planisme]]'', a new economical theory invented by the Belgian [[Henri de Man]], as well as with the [[Technocracy (bureaucratic)|technocratic]] ''[[Groupe X-Crise]]''. They influenced both [[Vichy France|Vichy]]'s ''[[Révolution nationale]]'' (''[[Jeune France]]'', [[Ecole des cadres d'Uriage]], etc.) and political programs of the [[French Resistance|Resistance]] (''[[Combat (newspaper)|Combat]]'', ''[[Défense de la France]]'', [[Organisation civile et militaire|OCM]], etc.) In November 1941, [[René Vincent]], in charge of Vichy [[censorship in France|censorship]] services, created the journal ''[[Idées]]'' (1941–44) which gathered the Non-Conformists who supported Marshal [[Philippe Pétain]]'s regime.<ref>Antoine Guyader (preface by [[Pascal Ory]]), ''La Revue ''Idées'' — Des Non-Conformistes en Révolution Nationale'', L'Harmattan, {{ISBN|2-296-01038-5}} {{fr icon}}</ref> |

|||

==Foreign policy== |

==Foreign policy== |

||

Revision as of 18:07, 8 November 2018

This article or section is in a state of significant expansion or restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. If this article or section has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. If you are the editor who added this template and you are actively editing, please be sure to replace this template with {{in use}} during the active editing session. Click on the link for template parameters to use.

This article was last edited by Rjensen (talk | contribs) 5 years ago. (Update timer) |

Interwar France covers the political, economic, diplomatic, cultural and social history of France, 1919-1939.

Wartime losses

Francis suffered severe human and economic damage during the war. The human losses included 1.3 million men killed, or 10.5 percent of the available Frenchmen. That compared to 9.8 percent for Germany and 5.1 percent for Great Britain. In addition 1.1 million veterans men were severely wounded and often incapacitated. Many hundreds of thousands of civilians had died in the Spanish influenza epidemic that struck as the war was ending. The population was further weakened by missing births, amounting to about 1.4 million while the menfolk were at war. In monetary terms, economist Alfred Sauvy estimated a loss of 55 billion francs (in 1913 value), or 15 months worth of national income that could never be restored. The harsh German occupation had wrecked special havoc on 13,000 square miles in northeastern France. In addition to the smashed up battlefields, the region's railways, bridges, mines, factories, commercial offices and private housing were all massively affected. Germans pillaged the factories and farms, removing machines and tools as well as 840,000 head of cattle, 400,000 horses 900,000 sheep, and 330,000 hogs. The government promised to make it good again, committing 20 billion francs. The plan was to have Germany repay all of this Through reparations. Repairs and rebuilding were highly successful in quick order.[1][2]

Economic and social growth

The interwar total population grew very slowly, from 38.8 million in 1921 to 41.2 million in 1936. Educationally, there was steady improvement, as secondary enrollment grew from 158 thousand, in 1921 to 248 thousand in 1936. University enrollment grew from 51 thousand to 72 thousand. In a typical year there were from 300 to 1200 strikes taking place, jumping to 17,000 in 1936, with the number of strikers soaring from 240,000 in 1929 to 2.4 million in 1936. As in other industrial countries, exports grew rapidly in the 1920s, then plunged to very low levels in the 1930s. The gross domestic product was quite stable in the 1930s, as France successfully resisted the worldwide Great Depression. Industrial production recovered prewar levels by 1924, and declined only by 10 percent during the depression. Throughout the interwar period, steel and coal were strong, while motor vehicles became the major new industrial sector of increased importance during the 1920s 1920s. [3]

Labor unions

Labor unions had supported the war effort and grew rapidly until 1919. The general strike and railway strikes of 1920 were a total failure. In the aftermath 25,000 railwaymen active in union affairs were fired and the companies blacklisted union leaders. Trade union membership plunged. In 1921 the General Confederation of Labour(C.G.T.) split permanently, with more extreme elements forming the Confédération générale du travail unitaire (C.G.T.U.) It enlisted the syndicalists who wanted direct union ownership and control of the factories by and for the benefit of the workers. It soon lost the spirit of revolutionary syndicalism and came under the close control of the Communist Party, which in turn was controlled by the Profintern (the Red Trade Union International based in the Kremlin).[4]

In the 1920s and 1930s the Paris Metal Union became the test bed for Communist unionism at the plant level. The model spread to all Communist unions as the Party shifted from winning votes at general elections to control of factory cells. A small number of disciplined Party members controlled the cells which then controlled the entire union at the factory. The strategy was a success and was essential to very rapid growth in the 1930s.[5]

Union membership doubled during the war and peaked at 2,000,000 for 1919, out of some 8,000,000 industrial workers, or about 25 per cent. After the plunge in 1921 membership slowly grew to 1,500,000 in 1930, or 19% of the 8 million employed that year. The heaviest losses came in metal factories, textile mills, and construction. The greatest density was in printing, where 40% were members. Blue collar government workers were increasingly unionized by 1930, especially the railways and trams.[6]

Great Depression

The Great Depression affected France from 1931 to 1939, but was milder than other industrial countries[7] While the economy in the 1920s grew at the very strong rate of 4.4% per year, the 1930s rate fell to only 0.6%.[8] The depression was relatively mild at first: unemployment peaked under 5%, the fall in production was at most 20% below the 1929 output; there was no banking crisis.[9] The depression had some effects on the local economy, which can partly explain the 6 February 1934 crisis and even more the formation of the Popular Front, led by SFIO socialist leader Léon Blum, who won the election of 1936.

The sour economic mood after 1932 heightened French exclusionism and xenophobia. The result was protectionism against importing foreign goods and allowing in foreign workers. Asylum seekers were not welcome--including thousands of Jews trying to flee Nazi Germany after 1933. The main reason was hostility to any foreign workers, and this in turn was connected to the lack of a legal framework for the effective treatment of refugees.[10] The middle classes resented Jews already in France, showing anger at competition for jobs or business. This fed anti-Semitism, which was more than a symbolic protest against the republic or communism. By the end of 1933, France began to expel refugee Jews and right-wing movements escalated their rhetorical anti-Semitism.[11]

Social and cultural trends

Religion

The great majority of the population used church services primarily to mark important life events, such as baptism, marriage and funerals. Otherwise, religiosity was steadily declining and already varied enormously across France. The largest groupings the devout Catholics, The passive Catholics, the anti-clerical secularists, and small minorities of Protestants and Jews. [12]

Pope Benedict XV (1914-1922) ended Pope Pius X's harsh anti-Modernist crusade, and returned to the tolerant policies of Pope Leo XIII. This enabled the French modernizers, such as Christian Democrat Marc Sangnier, leader of the Sillon movement To be restored to the Church's good graces. [13] The new spirit from Rome enabled a permanent end to the rancorous prewar battles between secularism on one hand and Catholic Church on the other. It had climaxed in a major victory for the anti-clerical Republicans in the 1905 French law on the Separation of the Churches and the State. That law disestablished the Catholic Church, and took legal control of all its buildings and lands.[14]

Reconciliation was enabled by the wartime dedication of so many Catholics fighting and dying for the nation; allegations of disloyalty disappeared. More immediately, the conservatives secured a large majority in the Chamber of Deputies In the 1919 elections and Aristide Briand took the opportunity for reconciliation. In 1920, 80 members of Parliament joined the delegation to Rome for the canonization of Joan of Arc. Formal diplomatic relations were reestablished in January 1921. In December 1923 the government set up diocesan associations under control of the Bishop for the administration of Church property which had been seized two decades earlier. In January 1924, the pope approved, and the church was reestablished in the dominant position in French society. [15] The Catholics set up numerous local organizations, especially youth groups, To try to combat falling activism among the remaining church members. In 1919 the Church established the French Confederation of Christian Workers (CFTC) a labor union to bargain with employers and act as a political force. It was in competition with socialist and communist labor unions. However, only a small fraction of industrial workers were unionized before the 1930s.

Expatriate culture

Expatriate Writers, artists, composers, and would-be intellectuals from around the world flocked to Paris to study, attend performances, meet and greet, and express their artistry in a highly supportive environment.[16] Many Americans came to escape the commercialism back home. Led by Gertrude Stein, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, E. E. Cummings, William Faulkner, and Katherine Anne Porter, they formed a lively colony that sought out new experiences and soon had a large impact on culture back home.[17] A new factor was the arrival of hundreds of college students stretching their experiences through one of several junior year abroad programs that began about 1923. They lived with French families and took classes at French universities under the close supervision of their American professor, for which they earned a full year's academic credit.[18] Many musicians came to study with Nadia Boulanger.

Black Paris

Aimé Césaire, a poet from Martinique, was a representative leader of the emerging black community of Paris in the 1920s and 1930s. He was a founder of the négritude movement, a racial identity movement for a community which included black immigrants from the French West Indies, the U.S., and France's colonies in Africa.[19] Other prominent leaders included Léopold Sédar Senghor (elected in 1960 as the first president of independent Senegal), and Léon Damas of French Guiana. These intellectuals disavowed colonialism, and argued for the importance of a Pan-African racial identity worldwide. writers generally used a realist literary style and often used Marxist rhetoric reshaped to the black radical tradition.[20]

American blacks made a dramatic impact by introducing New Orleans-style jazz.[21] The American music had a major impact as the avant garde welcomed what they called "wild sound" of rhythmic explosions that unleashed gyrations upon the dance floor. However, white French musicians based in dance halls softened the harsh and shocking American style and made it a popular favorite.[22]

Non-conformists of the 1930s

The "non-conformists of the 1930s were intellectuals seeking new solutions to face the political, economic and social crisis. The name was coined in 1969 by the historian Jean-Louis Loubet del Bayle to describe a movement which revolved around Emmanuel Mounier's personalism. They attempted to find a "third (communitarian) alternative" between socialism and capitalism, and opposed both liberalism/parliamentarism/democracy and fascism.[23][24]

Three main currents of non-conformists may be distinguished:

- The review Esprit, founded in 1931 by Emmanuel Mounier and which was the main mouthpiece of personalism.

- The Ordre nouveau (New Order) group, created by Alexandre Marc and influenced by Robert Aron and Arnaud Dandieu's works. Charles de Gaulle would have some contacts with them between the end of 1934 and the beginning of 1935.[23] Jean Coutrot, who became during the Popular Front vice-president of the Committee of Scientific Organisation of Labour of the Minister Charles Spinasse, participated in the technical reunions of Ordre nouveau.[25]

- The Jeune Droite (Young Right — a term coined by Mounier) that gathered young intellectuals who had more or less broken with the monarchist Action Française, including Jean de Fabrègues, Jean-Pierre Maxence, Thierry Maulnier, Maurice Blanchot, as well as the journals Les Cahiers, Réaction pour l'ordre, La Revue française or La Revue du Siècle.

These young intellectuals (most were about 25 years old) all considered that France was confronted by a "civilisation crisis" and opposed, despite their differences, what Mounier called the "established disorder" (le désordre établi). The latter was represented by capitalism, individualism, economic liberalism and materialism. Opposed both to Fascism and to Communism (qualified for the first as a "false Fascist-spiritualism [26]" and for the latter as plain materialism), they aimed at creating the conditions of a "spiritual revolution" which would simultaneously transform Man and things. They called for a "New Order", beyond individualism and collectivism, oriented towards a "federalist," "communautary and personalist" organisation of social relations.

The Non-Conformists were influenced both by French socialism, in particular by Proudhonism (an important influence of Ordre nouveau) and by Social Catholicism, which permeated Esprit and the Jeune Droite. They inherited from both currents a form of scepticism towards politics, which explains some anti-statism stances, and renewed interest in social and economical transformations.[27] Foreign influences were more restricted, and were limited to the discovery of the "precursors of existentialism" (Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Heidegger, Max Scheler) and contacts between Ordre nouveau and several members of the German Conservative Revolutionary movement.[28] They were in favor of decentralization, underscored the importance of intermediary bodies, and opposed finance capitalism.[28]

The movement was close to liberalism in the attention given to civil society and in its distrust of the state; but it also criticized liberal individualism and its negligence of "intermediate bodies" (family, village, etc.[29] — the reactionary writer Maurice Barrès also insisted on the latter). They were characterized by the will to find a "Third Way" between Socialism and Capitalism, individualism and collectivism, idealism and materialism and the left–right distinction in politics.[30]

After the February 6, 1934 riots organized by far-right leagues, the Non-Conformists split toward various directions. Bertrand de Jouvenel made the link between the Non-Conformists and the supporters of planisme, a new economical theory invented by the Belgian Henri de Man, as well as with the technocratic Groupe X-Crise. They influenced both Vichy's Révolution nationale (Jeune France, Ecole des cadres d'Uriage, etc.) and political programs of the Resistance (Combat, Défense de la France, OCM, etc.) In November 1941, René Vincent, in charge of Vichy censorship services, created the journal Idées (1941–44) which gathered the Non-Conformists who supported Marshal Philippe Pétain's regime.[31]

Foreign policy

French foreign and security policy after 1919 used traditional alliance strategies to weaken German's potential to threaten France and comply with the strict obligations devised by France in the Treaty of Versailles. The main diplomatic strategy came in response to the demands of the French army to form alliances against the German threat. Germany resisted then finally complied, aided by American money, and France took a more conciliatory policy by 1924 in response to pressure from Britain and the United States, as well as to French realization that its potential allies in Eastern Europe were weak and hard to coordinate.[32][33] It proved impossible to establish military alliances with the United States or Britain. A tentative Russian agreement in 1935 was politically suspect and was not implemented. [34] The alliances with Poland and Czechoslovakia; these proved to be weak ties that collapsed in the face of German threats in 1938 in 1939. [35]

1920s

France was part of the Allied force that occupied the Rhineland following the Armistice. Foch supported Poland in the Greater Poland Uprising and in the Polish–Soviet War and France also joined Spain during the Rif War. From 1925 until his death in 1932, Aristide Briand, as prime minister during five short intervals, directed French foreign policy, using his diplomatic skills and sense of timing to forge friendly relations with Weimar Germany as the basis of a genuine peace within the framework of the League of Nations. He realized France could neither contain the much larger Germany by itself nor secure effective support from Britain or the League.[36]

In January 1923 as a response to the failure of the German to ship enough coal as part of its reparations, France (and Belgium) occupied the industrial region of the Ruhr. Germany responded with passive resistance, including Printing fast amounts of marks To pay for the occupation, thereby causing runaway inflation. Inflation heavily damaged the German middle class (whose savings became worthless) but it also damaged the French franc. The intervention was a failure, and in summer 1924 France accepted the American solution to the reparations issues, as expressed in the Dawes Plan. According to the Dawes Plan, American banks made long-term loans to Germany which used the dollars to pay reparations. [37] The United States demanded repayment of the war loans, although the terms were slightly softened in 1926. All the loans, payments and reparations were suspended in 1931, and all were finally resolved in 1951.[38][39]

In the 1920s, France built the Maginot Line, an elaborate system of static border defences, designed to stop any German invasion. The Maginot Line did not extend into Belgium, where Germany attacked in 1940 and went around the French defenses. Military alliances were signed with weak powers in 1920–21, called the "Little Entente".[40]

Political trends

Parties

The Republican-Radical and Radical-Socialist Party, usually called the Radical Party, (1901-1940) was the 20th century version of the radical political movement founded by Leon Gambetta in the 1970s. It attracted 20-25% of the deputies elected in the interwar years and had a middle class base. The "radicalism" meant opposition to royalism and support for anti-clerical measures to weaken the role of Catholic Church in education and as an established church. Its program but was otherwise vaguely in favor of liberty, social progress, and peace. Its organizational structure was always much thinner than rival parties on the right (such as the Democratic Republican Alliance) or left (socialists and Communists). The party organizations at the departmental level were largely independent of Paris. The national conventions were attended by only a third of the delegates,and there was no official party newspaper. It split into moderate and Leftist wings, represented respectively by Edouard Herriot (1872–1957) and Edouard Daladier (1884–1970). "Socialism" in its title was misleading for it had little support among workers or labor unions. Its middle position made it a frequent partner in coalition governments, and its leaders increasingly focused on holding office and providing patronage to their followers. Other major leaders included Georges Clemenceau (1841-1929), Joseph Caillaux (1863-1944), and Aristide Briand (1862–1932).[41][42]

1920s

Domestic politics during the 1920's were a product of unresolved problems left by the war and peace, especially the economics of reconstruction and how to make Germany pay for it all. The great planners were Raymond Poincaré, Alexander Millerand and Aristide Briand. France had paid for the war with very heavily borrowing at home, and from Britain and the United States. Heavy inflation resulted. In 1922 Poincaré became Prime Minister. He jestified his strong anti-German policies:

- Germany's population was increasing, her industries were intact, she had no factories to reconstruct, she had no flooded mines. Her resources were intact, above and below ground... [i]n fifteen or twenty years Germany would be mistress of Europe. In front of her would be France with a population scarcely increased.[43]

Poincaré used German reparations to maintain the franc at a tenth of its prewar value, and pay for the reconstruction of the devastated areas. Berlin was unwilling to pay nearly as much as Paris demanded. Poincaré sent the French army to occupy the Ruhr industrial area (1922) to force a showdown. The British strongly objected, arguing that this "would only impair German recovery, topple the German government, [and] lead to internal anarchy and Bolshevism, without achieving the financial goals of the French."[44] The Germans practiced passive resistance, flooding the economy with paper money that damaged both the German and French economies. The standoff was solved by American dollars in the Dawes Plan--New York banks loaned money to Germany, which used the dollars for reparations to France, which then used the same dollars to repay Washington. Throughout the early postwar, Poincare';s political base was tghe conservative nationalist parliament elected in 1920. However at the next election (1924), a coalition of Radical Socialists and Socialists called the "Cartel des Gauches" ("Coalition of the Left") won a majority and Édouard Herriot of the Radical Socialist Party became prime minister. He was disillusioned by the imperialist thrust of the Versailles Treaty, and sought a stable international peace in rapprochement with the Soviet Union to block the rising German revanchist movement, especially after Hitler's coup d'etat in January 1933. [45]

1930s

Conservatism and fascism

The two major far-right parties were the French Social Party (Parti Social Français/Fiery Cross)) (PSF) and the French Popular Party (Parti Populaire Français) (PPF). The PSF was much larger, reaching as many as a million members, and grew increasingly conservative. The PPF was much smaller, with perhaps 50,000 members, and grew more fascist-like. The chief impact for both movements was to bring together their enemies on the left and center into the Popular Front.[46]

The Croix de Feu was originally an elite veterans' organization that François de La Rocque took over in 1929 and made a political movement. The Croix-de-Feu was dissolved in June 1936, by the Popular Front government, and de La Rocque quickly formed the new Parti Social Français or PSF. Both organizations were authoritarian and conservative, hostile to democracy and devoted to the defense of property, the family, and the nation against the threat of decay or leftist revolution. The motto of PSF was "Travail, famille, patrie" ("Work, family, fatherland"). The base was in urban areas, especially Paris, the industrial North, and Algeria. The members were young (born after 1890), middle class, with few blue collar or farm workers. PSF grew rapidly in the late 1930s, with more members than the Communists and Socialists combined. It reached out to include more workers and rural elements. De La Roche was a charismatic leader but a poor politician with vague ideas. His movement opposed the far-right Vichy regime and its leaders were arrested and the PSF vanished. It never invited to join a governing coalition. Whether or not it was "fascist" is debated by scholars. Many resemblances were there but not the key fascist promise of the creation of a revolutionary “new fascist man.” Instead PSF goal was to return to the past and rely upon the old traditional church and army.[47][48]

The Popular Front: 1936-1937

As the Great Depression finally hit France hard in 1932, the popular mood turned highly negative. A series of cabinets proved wholly ineffective, anger at the mounting unemployment caused Xena phobia, a closing of the borders, and a startling growth in anti-Semitism. Distrust of the entire political system grew rapidly, escalated by the dramatic Stavisky Affair. a massive financial fraud that involving many deputies and top government officials. The promise of democracy seemed a failure in France, and in followed many other countries as they turned toward authoritarian rule-- a trend begun by Lenin in Russia in 1918 and Mussolini in Italy in 1922 and continued in Spain, Portugal, Poland, the Baltic countries, the Balkans, Japan, Latin America, and most horrifying of all, by Hitler in Nazi Germany in January 1933. Now it threatened France. The exposure brought huge mobs into the streets of Paris. On February 6 and 7, 1934, sustained all night attacks took place against the police defending Parliament from assault by mostly right-wing attackers. The police Killed 15 demonstrators and halted their advance.[49] Journalist Alexander Werth argues:

- At that time the Croix de Feu, the Royalists, the Solidarité and the Jeunesses Patriotes had no more than a few thousand active members between them, and that they would have been incapable of a real armed uprising. What they reckoned on was the support of the Paris public as a whole; and the most that they could reasonably have aimed at was the resignation of the Daladier Government. When this happened, on February 7, Colonel de la Rocque announced that 'the first objective had been attained.' [50]

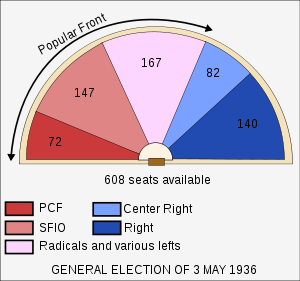

The 6 February outrage shocked the center and left, which had been feuding ceaselessly for decades. On February 12 by a huge counter-demonstration of the Left, in which Communist workers spontaneously joined with Radical Socialists and Socialists against what seemed to them to be a serious fascist threat. The center and left slowly began to assemble an unprecedented three-way coalition, with Socialist the largest party, followed by the Radicals and trailed by the Communists (PCF). Stalin had recently ordered that all Communist parties must stop fighting the socialists and combine an anti-fascist popular front, and it was carried out in France. The Communists supported the government, but refused to take any cabinet seats.[51]

New elections were held on 3 May 1936 and confirmed the political upheaval. Conservative forces were decimated and Socialist Léon Blum, as leader of the largest coalition party, SFIO, became prime minister. Suddenly there was a massive wave of strikes in which 2 million workers shut down French industry and paralyzed the forces of business and conservatism. This inspired the coalition government to hurriedly pass multiple packages of new programs designed for the benefit of the working-class.[52] The key provisions included immediate wage increases of 12 percent, general collective bargaining with labor unions, 40 hour week, paid vacations, compulsory arbitration of labor disputes, nationalization of the Bank of France, and nationalization of some key munitions plants. The conservative opposition was dissolved, most notably the Croix des Feu, but it reassembled itself quickly as a political party. The left had assumed reform such as this would liberate not just the workers but the entire economy. The economy did not respond well. Prices shot up, and inflation canceled the wage increases, while hurting the middle class by sharply cutting into their savings accounts. Industrial production did not increase, and militant workers made sure that even if demand was very strong, that factories which shut down after 40 hours. Unemployment remained high. The government deficit soared, And the government was forced to devalue the franc. Blum had never been accustomed to working with coalition partners, and his coalition started coming apart. It collapsed in June 1937 after 380 days in office. While the working-class elements praised and were always nostalgic about the Popular Front, the middle-class elements were outraged and felt betrayed.[53][54]

Appeasement and war 1938-1939

Appeasement was increasingly adopted as Germany grew stronger after 1933, for France suffered a stagnant economy, unrest in its colonies, and bitter internal political fighting. Appeasement say Martin Thomas was not a coherent diplomatic strategy nor a copying of the British.[55] France appeased Italy on the Ethiopia question because it could not afford to risk an alliance between Italy and Germany.[56]

When Hitler sent troops into the Rhineland—the part of Germany where no troops were allowed—neither Paris nor London would risk war, and nothing was done.[57]

The Blum government joined Britain in establishing an arms embargo during the Spanish Civil War (1936–39). Blum rejected support for the Spanish Republicans because of his fear that civil war might spread to deeply divided France. As the Republican cause faltered in Spain, Blum secretly supplied it the Republican cause with arms, funds and sanctuaries. Financial support in military cooperation with Poland was also a policy. The government nationalized arms suppliers, and dramatically increased its program of rearming the French military in a last-minute catch up with the Germans.[58]

Appeasement of Germany, in cooperation with Britain, was the policy after 1936, as France sought peace even in the face of Hitler's escalating demands. Édouard Daladier refused to go to war against Germany and Italy without British support as Neville Chamberlain wanted to save peace using the Munich Agreement in 1938.[59][60] France's military alliance with Czechoslovakia was sacrificed at Hitler's demand when France and Britain agreed to his terms at Munich in 1938.[61][62]

Overseas empire

French census statistics from 1931 show an imperial population, outside of France itself, of 64.3 million people living on 11.9 million square kilometers. Of the total population, 39.1 million lived in Africa and 24.5 million lived in Asia; 700,000 lived in the Caribbean area or islands in the South Pacific. The largest colonies were Indochina with 21.5 million (in five separate colonies), Algeria with 6.6 million, Morocco, with 5.4 million, and West Africa with 14.6 million in nine colonies. The total includes 1.9 million Europeans, and 350,000 "assimilated" natives.[63]

A hallmark of the French colonial project from the late 19th century to the post-World War Two era was the civilising mission (mission civilisatrice). The principle was that it was France's duty to bring civilisation to benighted peoples.[64] As such, colonial officials undertook a policy of Franco-Europeanisation in French colonies, most notably French West Africa and Madagascar.

Catholicism was a major factor in the civilising mission, and many missionaries were sent. Often they operated schools and hospitals.[65] During the 19th century, French citizenship along with the right to elect a deputy to the French Chamber of Deputies was granted to the four old colonies of Guadeloupe, Martinique, Guyanne, and Réunion as well as to the residents of the "Four Communes" in Senegal. Typically the elected deputies were white Frenchmen, although there were some blacks, such as the Senegalese Blaise Diagne, who was elected in 1914.[66] Elsewhere, in the largest and most populous colonies, a strict separation between "sujets français" (all the natives) and "citoyens français" (all males of European extraction) with different rights and duties was maintained until 1946.

French colonial law held that the granting of French citizenship to natives was a privilege and not a right. Two 1912 decrees dealing with French West Africa and French Equatorial Africa enumerated the conditions that a native had to meet in order to be granted French citizenship (they included speaking and writing French, earning a decent living and displaying good moral standards). For the 116 years from 1830 to 1946, only between 3,000 and 6,000 native Algerians were granted French citizenship. Well under 10 percent of the Algerian population was of European descent, chiefly Spanish and Italian Followed by families who migrated from mainland France. They controlled virtually the entire Algerian economy and political system, while few Muslims progressed out of poverty. In French West Africa, outside of the Four Communes, there were 2,500 "citoyens indigènes" out of a total population of 15 million.

French conservatives had been denouncing the assimilationist policies as products of a dangerous liberal fantasy. In the Protectorate of Morocco, the French administration attempted to use urban planning and colonial education to prevent cultural mixing and to uphold the traditional society upon which the French depended for collaboration, with mixed results. After World War II, the segregationist approach modeled in Morocco had been discredited by its connections to Vichyism, and assimilationism enjoyed a brief renaissance.[66]

Critics of French colonialism gained an international audience in the 1920s, and often used documentary reportage and access to agencies such as the League of Nations and the International Labour Organization to make their protests heard. The main criticism was the high level of violence and suffering among the natives. Major critics included Albert Londres, Félicien Challaye, and Paul Monet, whose books and articles were widely read.[67]

See also

- French Third Republic#Interwar period

- 1919 in France

- 1920 in France

- 1921 in France

- 1922 in France

- 1923 in France

- 1924 in France

- 1925 in France

- 1926 in France

- 1927 in France

- 1928 in France

- 1929 in France

- 1930 in France

- 1931 in France

- 1932 in France

- 1933 in France

- 1934 in France

- 1935 in France

- 1936 in France

- 1937 in France

- 1938 in France

- 1939 in France

- Interwar period, worldwide

- Interwar Britain

Notes

- ^ Philippe Bernard and Henri Dubief, The Decline of the Third Republic, 1914–1938 (1988) pp 78-82.

- ^ Frank Lee Benns, Europe since 1914 (8th ed. 1965) pp 303-4.

- ^ Thelma Liesner, One Hundred Years of Economic Statistics (Facts on File, 1989), pp 177-200.

- ^ Alexander Werth and D. W. Brogan, The Twilight of France, 1933-1940 (2nd ed. 1942) p 102.

- ^ Michael Torigian, "From guinea pig to prototype: Communist Labour policy in the Paris metal industry, 1922-35," Journal of Contemporary History (1997) 32#4 pp 465-81.

- ^ D. J. Saposs, Labour Movement in Post-War France (1931) pp 117-25. online

- ^ Henry Laufenburger, "France and the Depression," International Affairs (1936) 15#2 pp. 202–224 JSTOR 2601740

- ^ Jean-Pierre Dormois, The French Economy in the Twentieth Century (2004) p 31

- ^ Paul Beaudry and Franck Portier, "The French Depression in the 1930s," Review of Economic Dynamics (2002) 5:73–99 doi:10.1006/redy.2001.0143

- ^ Greg Burgess, "France and the German refugee crisis of 1933." French History 16.2 (2002): 203-229.

- ^ Vicki Caron, "The Antisemitic revival in France in the 1930s: the socioeconomic dimension reconsidered." Journal of Modern History 70.1 (1998): 24-73. online

- ^ W. D. Halls, Politics, Society and Christianity in Vichy France (1992) pp 3-38 Online

- ^ Gearóid Barry, "Rehabilitating a Radical Catholic: Pope Benedict XV and Marc Sangnier, 1914–1922." Journal of Ecclesiastical History 60.3 (2009): 514-533.

- ^ Jean-Marie Mayeur and Madeleine Rebérioux, The Third Republic from its Origins to the Great War, 1871–1914 (1984) pp 227–44.

- ^ J. de Fabrègues, J. "The Re-establishment of Relations between France and the Vatican in 1921." Journal of Contemporary History 2.4 (1967): 163-182.

- ^ Arlen J. Hansen, Expatriate Paris: A Cultural and Literary Guide to Paris of the 1920s (2014)

- ^ Brooke L. Blower, Becoming Americans in Paris: Transatlantic politics and culture between the World Wars (2011)

- ^ Whitney Walton, "Internationalism and the junior year abroad: American students in France in the 1920s and 1930s." Diplomatic History 29.2 (2005): 255-278.

- ^ Tyler Stovall, "Aimé Césaire and the making of black Paris." French Politics, Culture & Society 27#3 (2009): 44-46.

- ^ Gary Wilder, The French Imperial Nation-State: Negritude & Colonial Humanism Between the Two World Wars (2005).

- ^ Tyler Stovall, Paris noir: African Americans in the city of light (1996).

- ^ Jeffrey H. Jackson, "Music‐Halls and the Assimilation of Jazz in 1920s Paris." Journal of Popular Culture 34#2 (2000): 69-82.

- ^ a b Account of Jean-Louis Loubet del Bayle's book in the Archives de Sciences Sociales des Religions n°118, on the EHESS website Template:Fr icon

- ^ John Hellman (2002). Communitarian Third Way: Alexandre Marc and Ordre Nouveau, 1930-2000. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-7735-2376-0.

- ^ Biographical notice of Jean Coutrot, Centre d'histoire de Sciences Po Template:Fr icon

- ^ Prospectus de présentation de la revue "Esprit" Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine, presented by Alain-Gérard Slama, on-line course of Sciences Po, 18 May 2007 Template:Fr icon

- ^ Jean-Louis Loubet del Bayle, A 2001 Interview (p.3) in the Revue Jibrile Template:Fr icon

- ^ a b Jean-Louis Loubet del Bayle, A 2001 Interview (p.4) in the Revue Jibrile Template:Fr icon

- ^ Jean-Louis Loubet del Bayle, A 2001 Interview (p.5) in the Revue Jibrile Template:Fr icon

- ^ Jean-Louis Loubet del Bayle, A 2001 Interview (p.6) in the Revue Jibrile Template:Fr icon

- ^ Antoine Guyader (preface by Pascal Ory), La Revue Idées — Des Non-Conformistes en Révolution Nationale, L'Harmattan, ISBN 2-296-01038-5 Template:Fr icon

- ^ Peter Jackson, "France and the problems of security and international disarmament after the first world war." Journal of Strategic Studies 29#2 (2006): 247–280.

- ^ Nicole Jordan, "The Reorientation of French Diplomacy in the mid-1920s: the Role of Jacques Seydoux." English Historical Review 117.473 (2002): 867–888.

- ^ Richard Overy (1999). The road to war. Penguin. p. 140-41. ISBN 978-0-14-028530-7.

- ^ Piotr Stefan Wandycz, The Twilight of French Eastern Alliances, 1926-1936: French-Czechoslovak-Polish Relations from Locarno to the Remilitarization of the Rhineland (1988) ch 1 online

- ^ Eugen Weber, The Hollow Years: France in the 1930s (1996) p. 125

- ^ Conan Fischer, The Ruhr Crisis 1923-1924 (2003).

- ^ Adamthwaite, Grandeur and Misery pp 29-30, 48.

- ^ Philip A. Grant Jr. and Martin Schmidt, "France and the American War Debt Controversy, 1919-1929" Proceedings of the Western Society for French History (1981), Vol. 9, pp 372-382.

- ^ William Allcorn, The Maginot Line 1928–45 (2012).

- ^ Peter J. Larmour, The French Radical Party in the 1930's (1964).

- ^ Mildred Schlesinger, "The Development of the Radical Party in the Third Republic: The New Radical Movement, 1926-32" Journal of Modern History 46#3 (1974), pp. 476-501 online

- ^ Étienne Mantoux, The Carthaginian Peace, or The Economic Consequences of Mr. Keynes (1946), p. 23.

- ^ Ephraim Maisel (1994). The Foreign Office and Foreign Policy, 1919-1926. Sussex Academic Press. pp. 122–23.

- ^ Alexander Werth, Which Way France (1937) pp 21-38 online

- ^ Sean Kennedy, "The End of Immunity? Recent Work on the Far Right in Interwar France." Historical Reflections/Réflexions Historiques 34.2 (2008): 25-45.

- ^ Sean Kennedy, Reconciling France Against Democracy: The Croix-de-Feu and the Parti Social Français, 1927-45 (2007).

- ^ John Bingham, "Defining French fascism, finding fascists in France." Canadian Journal of History 29.3 (1994): 525-544.

- ^ Geoffrey Warner,"The Stavisky Affair and the Riots of February 6th 1934." History Today (1958): 377-85.

- ^ Alexander Werth and D. W. Brogan, The Twilight of France, 1933-1940 (1942) p 16 online

- ^ Joel Colton, Léon Blum (1966) pp 92–126.

- ^ Colton, Léon Blum (1966) pp 160-97.

- ^ Gordon Wright, France in Modern Times (1995) pp 360–369.

- ^ Colton, Léon Blum (1966) pp 126–273.

- ^ Martin Thomas, "Appeasement in the Late Third Republic," Diplomacy and Statecraft 19#3 (2008): 566–607.

- ^ Reynolds M. Salerno, "The French Navy and the Appeasement of Italy, 1937-9," English Historical Review 112#445 (1997): 66–104.

- ^ Stephen A. Schuker, "France and the Remilitarization of the Rhineland, 1936," French Historical Studies 14.3 (1986): 299–338.

- ^ Larkin, France since the Popular Front, (1988) pp 45-62

- ^ Martin Thomas (1996). Britain, France and Appeasement: Anglo-French Relations in the Popular Front Era. Berg. p. 137.

- ^ Maurice Larkin, France since the Popular Front: Government and People, 1936–1986 (1988) pp 63-81

- ^ Nicole Jordan, "Léon Blum and Czechoslovakia, 1936–1938." French History 5#1 (1991): 48–73.

- ^ Martin Thomas, "France and the Czechoslovak crisis," Diplomacy and Statecraft 10.23 (1999): 122–159.

- ^ Herbert Ingram Priestley, France overseas: a study of modern imperialism (1938) pp. 440–41.

- ^ Raymond F. Betts (2005). Assimilation and Association in French Colonial Theory, 1890–1914. University of Nebraska Press. p. 10. ISBN 9780803262478.

- ^ Elizabeth Foster, Faith in Empire: Religion, Politics, and Colonial Rule in French Senegal, 1880–1940 (2013)

- ^ a b Spencer Segalla, The Moroccan Soul: French Education, Colonial Ethnology, and Muslim Resistance, 1912–1956. 2009)

- ^ J.P. Daughton, "Behind the Imperial Curtain: International Humanitarian Efforts and the Critique of French Colonialism in the Interwar Years", French Historical Studies, (2011) 34#3 pp. 503–28

Further reading

- Bell,David, et al. A Biographical Dictionary of French Political Leaders since 1870 (1990)

- Bernard, Philippe, and Henri Dubief. The Decline of the Third Republic, 1914–1938 (1988) excerpt and text search, by French scholars

- Brogan, D. W The development of modern France (1870–1939) (1953) online

- Bury, J. P. T. France, 1814–1940 (2003) ch 9–16

- Fortescue, William. The Third Republic in France, 1870–1940: Conflicts and Continuities (2000) excerpt and text search

- Hutton, Patrick H., ed. Historical Dictionary of the Third French Republic, 1870–1940 (Greenwood, 1986) online edition

- Larkin, Maurice. France since the Popular Front: Government and People, 1936–1986 (Oxford UP, 1988) online free to borrow

- Shirer, William L. The Collapse of the Third Republic: An Inquiry into the Fall of France, (1969) excerpt

- Thomson, David. Democracy in France: The Third Republic (1952) online

- Wolf, John B. France: 1815 to the Present (1940) online free pp 349–501.

- Wright, Gordon. France in Modern Times (5th ed. 1995) pp 221–382

Scholarly studies

- Adamthwaite, Anthony. Grandeur and Misery: France's Bid for Power in Europe 1914–1940 (1995) excerpt and text search

- Copley, A. R. H. Sexual Moralities in France, 1780–1980: New Ideas on the Family, Divorce and Homosexuality (1992)

- Davis, Richard. Anglo-French relations before the Second World War: appeasement and crisis (Springer, 2001).

- Duroselle, Jean-Baptiste. France and the Nazi Threat: The Collapse of French Diplomacy 1932–1939 (2004); Translation of his highly influential La décadence, 1932–1939 (1979)

- Hansen, Arlen J. Expatriate Paris: A Cultural and Literary Guide to Paris of the 1920s (1920)

- Jackson, Julian. The Politics of Depression in France 1932–1936 (2002) excerpt and text search

- Jackson, Julian. The Popular Front in France: Defending Democracy, 1934-38 (1990).

- Kennedy, Sean. Reconciling France Against Democracy: the Croix de feu and the Parti social français, 1927–1945 (McGill-Queen's Press-MQUP, 2007)

- Kreuzer, Marcus. Institutions and Innovation: Voters, Parties, and Interest Groups in the Consolidation of Democracy—France and Germany, 1870–1939 (U. of Michigan Press, 2001)

- Larmour, Peter J. The French Radical Party in the 1930's (1964).

- MacMillan, Margaret. Paris 1919: six months that changed the world (2007). The peace conference.

- McAuliffe, Mary. When Paris Sizzled: The 1920s Paris of Hemingway, Chanel, Cocteau, Cole Porter, Josephine Baker, and Their Friends (2016) excerpt

- Nere, J. Foreign Policy of France 1914–45 (2010)

- Passmore, Kevin. "The French Third Republic: Stalemate Society or Cradle of Fascism?" French History (1993) 7#4 417–449 doi=10.1093/fh/7.4.417

- Quinn, Frederick. The French Overseas Empire (2001).

- Reynolds, Siân. France between the Wars: Gender and Politics (1996) Online

- Weber, Eugen. The Hollow Years: France in the 1930s (1996)

- Werth, Alexander and D. W. Brogan. The Twilight of France, 1933-1940 (1942) Online

- Zeldin, Theodore. France: 1848–1945: Politics and Anger; Anxiety and Hypocrisy; Taste and Corruption; Intellect and Pride; Ambition and Love (2 vol 1979), topical history

Historiography

- Cairns, John C. "Some Recent Historians and the 'Strange Defeat' of 1940" Journal of Modern History 46#1 (1974), pp. 60-85 online

- Jackson, Peter. "Post-War Politics and the Historiography of French Strategy and Diplomacy Before the Second World War." History Compass 4.5 (2006): 870-905.