History of espionage: Difference between revisions

→First World War: Dreyfus |

|||

| Line 92: | Line 92: | ||

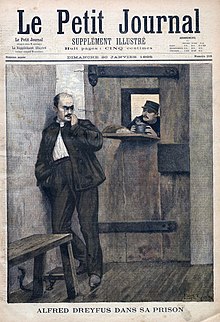

[[File:Dreyfus-in-Prison-1895.jpg|thumb|Cover of the ''Petit Journal'' of 20 January 1895, covering the [[Dreyfuss Affair]]]] |

|||

In the 1890s [[Dreyfus affair|Alfred Dreyfus]], a Jewish artillery captain in the French army, was twice falsely convicted of passing military secrets to the Germans. The case convulsed France regarding antisemitism, and xenophobia, for a decade until he was exonerated. It raised public awareness of the rapidly developing world of espionage.<ref>Douglas Porch, ''The French Secret Services: From the Dreyfus Affair to the Gulf War'' (1995).</ref><ref>Allan Mitchell, "The Xenophobic Style: French Counterespionage and the Emergence of the Dreyfus Affair." ''Journal of Modern History'' 52.3 (1980): 414-425. [https://www.jstor.org/stable/1876926 online]</ref> |

|||

==20th century== |

|||

=== First World War === |

=== First World War === |

||

[[File:Dreyfus-in-Prison-1895.jpg|thumbnail|Cover of the ''Petit Journal'' of 20 January 1895, covering the arrest of Captain [[Alfred Dreyfus]] for espionage and treason. The case convulsed France and raised public awareness of the rapidly developing world of espionage.]] |

|||

By the outbreak of the [[First World War]] in 1914 all the major powers had highly sophisticated structures in place for the training and handling of spies and for the processing of the [[intelligence]] information obtained through espionage. The figure and mystique of the [[spy]] had also developed considerably in the public eye. The [[Dreyfus Affair]], which involved international espionage and [[treason]], contributed much to public interest in espionage<ref>Cook, Chris. ''Dictionary of Historical Terms'' (1983) p. 95.</ref><ref>Miller, Toby. ''Spyscreen: Espionage on Film and TV from the 1930s to the 1960s'' Oxford University Press, 2003 {{ISBN|0-19-815952-8}} p. 40-41</ref> from 1894 onwards. |

By the outbreak of the [[First World War]] in 1914 all the major powers had highly sophisticated structures in place for the training and handling of spies and for the processing of the [[intelligence]] information obtained through espionage. The figure and mystique of the [[spy]] had also developed considerably in the public eye. The [[Dreyfus Affair]], which involved international espionage and [[treason]], contributed much to public interest in espionage<ref>Cook, Chris. ''Dictionary of Historical Terms'' (1983) p. 95.</ref><ref>Miller, Toby. ''Spyscreen: Espionage on Film and TV from the 1930s to the 1960s'' Oxford University Press, 2003 {{ISBN|0-19-815952-8}} p. 40-41</ref> from 1894 onwards. |

||

| Line 134: | Line 138: | ||

In the Telegram's [[plain text]], [[Nigel de Grey]] and [[William Montgomery (cryptographer)|William Montgomery]] learned of the German Foreign Minister [[Arthur Zimmermann]]'s offer to Mexico to join the war as a German ally. The telegram was made public by the United States, which declared war on Germany on 6 April 1917. This event demonstrated how the course of a war could be changed by effective intelligence operations.<ref>{{cite book |title=The Zimmermann Telegram |last=[[Barbara Tuchman|Tuchman]] |first=Barbara W. |year=1958 |publisher=Ballantine Books |location=New York |isbn=0-345-32425-0 |ref=harv}}</ref> |

In the Telegram's [[plain text]], [[Nigel de Grey]] and [[William Montgomery (cryptographer)|William Montgomery]] learned of the German Foreign Minister [[Arthur Zimmermann]]'s offer to Mexico to join the war as a German ally. The telegram was made public by the United States, which declared war on Germany on 6 April 1917. This event demonstrated how the course of a war could be changed by effective intelligence operations.<ref>{{cite book |title=The Zimmermann Telegram |last=[[Barbara Tuchman|Tuchman]] |first=Barbara W. |year=1958 |publisher=Ballantine Books |location=New York |isbn=0-345-32425-0 |ref=harv}}</ref> |

||

=== Russian Revolution === |

=== Russian Revolution === |

||

The outbreak of revolution in Russia and the subsequent seizure of power by the [[Bolsheviks]], a party deeply hostile towards the capitalist powers, was an important catalyst for the development of modern international espionage techniques. A key figure was [[Sidney Reilly]], a Russian-born adventurer and secret agent employed by [[Scotland Yard]] and the [[Secret Intelligence Service]]. He set the standard for modern espionage, turning it from a gentleman's amateurish game to a ruthless and professional methodology for the achievement of military and political ends. Reilly's career culminated in an failed attempt to depose the Bolshevik Government and assassinate [[Vladimir Ilyich Lenin]].<ref name="Lockhart Plot">Richard B. Spence, ''Trust No One: The Secret World Of Sidney Reilly''; 2002, Feral House, {{ISBN|0-922915-79-2}}.</ref> |

The outbreak of revolution in Russia and the subsequent seizure of power by the [[Bolsheviks]], a party deeply hostile towards the capitalist powers, was an important catalyst for the development of modern international espionage techniques. A key figure was [[Sidney Reilly]], a Russian-born adventurer and secret agent employed by [[Scotland Yard]] and the [[Secret Intelligence Service]]. He set the standard for modern espionage, turning it from a gentleman's amateurish game to a ruthless and professional methodology for the achievement of military and political ends. Reilly's career culminated in an failed attempt to depose the Bolshevik Government and assassinate [[Vladimir Ilyich Lenin]].<ref name="Lockhart Plot">Richard B. Spence, ''Trust No One: The Secret World Of Sidney Reilly''; 2002, Feral House, {{ISBN|0-922915-79-2}}.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 14:16, 19 September 2018

Espionage, as well as other intelligence assessment, has existed since ancient times.

Early history

Events involving espionage are well documented throughout history. The ancient writings of Chinese and Indian military strategists such as Sun-Tzu and Chanakya contain information on deception and subversion. Sun Tzu stressed the need for military intelligence. Chanakya's student Chandragupta Maurya, founder of the Maurya Empire in India, made use of assassinations, spies and secret agents, which are described in Chanakya's Arthashastra. The ancient Egyptians had a thoroughly developed system for the acquisition of intelligence, and the Hebrews used spies as well, as in the story of Rahab. Spies were also prevalent in the Greek and Roman empires.[1] During the 13th and 14th centuries, the Mongols relied heavily on espionage in their conquests in Asia and Europe. Feudal Japan often used ninjas to gather intelligence.

A significant milestone was the establishment of an effective intelligence service under King David IV of Georgia at the beginning of 12th century or possibly even earlier. Called mstovaris, these organized spies performed crucial tasks, like uncovering feudal conspiracies, conducting counter-intelligence against enemy spies, and infiltrating key locations, e.g. castles, fortresses and palaces.[2]

Aztecs used Pochtecas, people in charge of commerce, as spies and diplomats, and had diplomatic immunity. Along with the pochteca, before a battle or war, secret agents, quimitchin, were sent to spy amongst enemies usually wearing the local costume and speaking the local language, techniques similar to modern secret agents.[3]

Many modern espionage methods were established by Francis Walsingham in Elizabethan England.[4] Walsingham's staff in England included the cryptographer Thomas Phelippes, who was an expert in deciphering letters and forgery, and Arthur Gregory, who was skilled at breaking and repairing seals without detection.[5]

In 1585, Mary, Queen of Scots was placed in the custody of Sir Amias Paulet, who was instructed to open and read all of Mary's clandestine correspondence.[5] In a successful attempt to expose her, Walsingham arranged a single exception: a covert means for Mary's letters to be smuggled in and out of Chartley in a beer keg. Mary was misled into thinking these secret letters were secure, while in reality they were deciphered and read by Walsingham's agents.[5] He succeeded in intercepting letters that indicated a conspiracy to displace Elizabeth I with Mary, Queen of Scots.

In foreign intelligence, Walsingham's extensive network of "intelligencers", who passed on general news as well as secrets, spanned Europe and the Mediterranean.[5] While foreign intelligence was a normal part of the principal secretary's activities, Walsingham brought to it flair and ambition, and large sums of his own money.[6] He cast his net more widely than others had done previously: expanding and exploiting links across the continent as well as in Constantinople and Algiers, and building and inserting contacts among Catholic exiles.[5]

19th century

Modern tactics of espionage and dedicated government intelligence agencies were developed over the course of the late 19th century. A key background to this development was the Great Game, a period denoting the strategic rivalry and conflict that existed between the British Empire and the Russian Empire throughout Central Asia. To counter Russian ambitions in the region and the potential threat it posed to the British position in India, a system of surveillance, intelligence and counterintelligence was built up in the Indian Civil Service. The existence of this shadowy conflict was popularised in Rudyard Kipling's famous spy book, Kim, where he portrayed the Great Game (a phrase he popularised) as an espionage and intelligence conflict that 'never ceases, day or night'.

Although the techniques originally used were distinctly amateurish – British agents would often pose unconvincingly as botanists or archaeologists – more professional tactics and systems were slowly put in place. In many respects, it was here that a modern intelligence apparatus with permanent bureaucracies for internal and foreign infiltration and espionage was first developed. A pioneering cryptographic unit was established as early as 1844 in India, which achieved some important successes in decrypting Russian communications in the area.[7]

The establishment of dedicated intelligence organizations was directly linked to the colonial rivalries between the major European powers and the accelerating development of military technology.

An early source of military intelligence was the diplomatic system of military attachés (an officer attached to the diplomatic service operating through the embassy in a foreign country), that became widespread in Europe after the Crimean War. Although officially restricted to a role of transmitting openly received information, they were soon being used to clandestinely gather confidential information and in some cases even to recruit spies and to operate de facto spy rings.

American Civil War 1861-1865

Tactical or battlefield intelligence became very vital to both armies in the field during the American Civil War. Allan Pinkerton, Who operated a pioneer Detective agency, served as head of the Union Intelligence Service during the first two years. He thwarted the assassination plot in Baltimore while guarding President-elect Abraham Lincoln. Pinkerton agents often worked undercover as Confederate soldiers and sympathizers to gather military intelligence. Pinkerton himself served on several undercover missions. He worked across the Deep South in the summer of 1861, collecting information on fortifications and Confederate plans. He was found out in Memphis and barely escaped with his life. Pinkerton's agency specialized in counter-espionage, identifying Confederate spies in the Washington area. Pinkerton played up to the demands of General George McClellan with exaggerated overestimates of the strength of Confederate forces in Virginia. McClellan mistakenly thought he was outnumbered, and played a very cautious role.[8][9] Spies and scouts typically reported directly to the commanders of armies in the field. They provided details on troop movements and strengths. The distinction between spies and scouts was one that had life or death consequences. If a suspect was seized while in disguise and not in his army's uniform, the sentence was often to be hanged.[10]

Intelligence gathering for the Confederates focused on Alexandria, Virginia, and the surrounding area. Thomas Jordan created a network of agents that included Rose O'Neal Greenhow. Greenhow delivered reports to Jordan via the “Secret Line,” the system used to smuggle letters, intelligence reports, and other documents to Confederate officials. The Confederacy’s Signal Corps was devoted primarily to communications and intercepts, but it also included a covert agency called the Confederate Secret Service Bureau, which ran espionage and counter-espionage operations in the North including two networks in Washington.[11][12]

In both armies, the cavalry service was the main instrument in military intelligence, using direct observation, Drafting map, and obtaining copies of local maps and local newspapers.[13] When General Robert E Lee invaded the North in June 1863, his cavalry commander J. E. B. Stuart went on a long unauthorized raid, so Lee was operating blind, unaware that he was being trapped by Union forces. Lee later said that his Gettysburg campaign, "was commenced in the absence of correct intelligence. It was continued in the effort to overcome the difficulties by which we were surrounded."[14]

Military Intelligence

Shaken by the revolutionary years 1848–1849, the Austrian Empire founded the Evidenzbureau in 1850 as the first permanent military intelligence service. It was first used in the 1859 Austro-Sardinian war and the 1866 campaign against Prussia, albeit with little success. The bureau collected intelligence of military relevance from various sources into daily reports to the Chief of Staff (Generalstabschef) and weekly reports to Emperor Franz Joseph. Sections of the Evidenzbureau were assigned different regions, the most important one was aimed against Russia.

During the Crimean War, the Topographical & Statistic Department T&SD was established within the British War Office as an embryonic military intelligence organization. The department initially focused on the accurate mapmaking of strategically sensitive locations and the collation of militarily relevant statistics. After the deficiencies in the British army's performance during the war became known a large-scale reform of army institutions was overseen by the Edward Cardwell. As part of this, the T&SD was reorganized as the Intelligence Branch of the War Office in 1873 with the mission to "collect and classify all possible information relating to the strength, organization etc. of foreign armies... to keep themselves acquainted with the progress made by foreign countries in military art and science..."[15]

The French Ministry of War authorized the creation of the Deuxième Bureau on June 8, 1871, a service charged with performing "research on enemy plans and operations."[16] This was followed a year later by the creation of a military counter-espionage service. It was this latter service that was discredited through its actions over the notorious Dreyfus Affair, where a French Jewish officer was falsely accused of handing over military secrets to the Germans. As a result of the political division that ensued, responsibility for counter-espionage was moved to the civilian control of the Ministry of the Interior.

Field Marshal Helmuth von Moltke established a military intelligence unit, Abteilung (Section) IIIb, to the German General Staff in 1889 which steadily expanded its operations into France and Russia. The Italian Ufficio Informazioni del Commando Supremo was put on a permanent footing in 1900. After Russia's defeat in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05, Russian military intelligence was reorganized under the 7th Section of the 2nd Executive Board of the great imperial headquarters.[17]

Naval Intelligence

It was not just the army that felt a need for military intelligence. Soon, naval establishments were demanding similar capabilities from their national governments to allow them to keep abreast of technological and strategic developments in rival countries.

The Naval Intelligence Division was set up as the independent intelligence arm of the British Admiralty in 1882 (initially as the Foreign Intelligence Committee) and was headed by Captain William Henry Hall.[18] The division was initially responsible for fleet mobilization and war plans as well as foreign intelligence collection; in the 1900s two further responsibilities – issues of strategy and defence and the protection of merchant shipping – were added.

Naval intelligence originated in the same year in the US and was founded by the Secretary of the Navy, William H. Hunt "...for the purpose of collecting and recording such naval information as may be useful to the Department in time of war, as well as in peace." This was followed in October 1885 by the Military Information Division, the first standing military intelligence agency of the United States with the duty of collecting military data on foreign nations.[19]

In 1900, the Imperial German Navy established the Nachrichten-Abteilung, which was devoted to gathering intelligence on Britain. The navies of Italy, Russia and Austria-Hungary set up similar services as well.

Civil intelligence agencies

Integrated intelligence agencies run directly by governments were also established. The British Secret Service Bureau was founded in 1909 as the first independent and interdepartmental agency fully in control over all government espionage activities.

At a time of widespread and growing anti-German feeling and fear, plans were drawn up for an extensive offensive intelligence system to be used as an instrument in the event of a European war. Due to intense lobbying by William Melville after he obtained German mobilization plans and proof of their financial support to the Boers, the government authorized the creation of a new intelligence section in the War Office, MO3 (subsequently redesignated M05) headed by Melville, in 1903. Working under cover from a flat in London, Melville ran both counterintelligence and foreign intelligence operations, capitalizing on the knowledge and foreign contacts he had accumulated during his years running Special Branch.

Due to its success, the Government Committee on Intelligence, with support from Richard Haldane and Winston Churchill, established the Secret Service Bureau in 1909. It consisted of nineteen military intelligence departments – MI1 to MI19, but MI5 and MI6 came to be the most recognized as they are the only ones to have remained active to this day.

The Bureau was a joint initiative of the Admiralty, the War Office and the Foreign Office to control secret intelligence operations in the UK and overseas, particularly concentrating on the activities of the Imperial German Government. Its first director was Captain Sir George Mansfield Smith-Cumming. In 1910, the bureau was split into naval and army sections which, over time, specialised in foreign espionage and internal counter-espionage activities respectively. The Secret Service initially focused its resources on gathering intelligence on German shipbuilding plans and operations. Espionage activity in France was consciously refrained from, so as not to jeopardize the burgeoning alliance between the two nations.

For the first time, the government had access to a peace-time, centralized independent intelligence bureaucracy with indexed registries and defined procedures, as opposed to the more ad hoc methods used previously. Instead of a system whereby rival departments and military services would work on their own priorities with little to no consultation or co-operation with each other, the newly established Secret Intelligence Service was interdepartmental, and submitted its intelligence reports to all relevant government departments.[20]

Counterintelligence

As espionage became more widely used, it became imperative to expand the role of existing police and internal security forces into a role of detecting and countering foreign spies. The Austro-Hungarian Evidenzbureau was entrusted with the role from the late 19th century to counter the actions of the Pan-Slavist movement operating out of Serbia.

As mentioned above, after the fallout from the Dreyfus Affair in France, responsibility for military counter-espionage was passed in 1899 to the Sûreté générale – an agency originally responsible for order enforcement and public safety – and overseen by the Ministry of the Interior.[16]

The Okhrana[21] was initially formed in 1880 to combat political terrorism and left-wing revolutionary activity throughout the Russian Empire, but was also tasked with countering enemy espionage.[22] Its main concern was the activities of revolutionaries, who often worked and plotted subversive actions from abroad. It created an antenna in Paris run by Pyotr Rachkovsky to monitor their activities. The agency used many methods to achieve its goals, including covert operations, undercover agents, and "perlustration" — the interception and reading of private correspondence. The Okhrana became notorious for its use of agents provocateurs who often succeeded in penetrating the activities of revolutionary groups including the Bolsheviks.[23]

In Britain, the Secret Service Bureau was split into a foreign and counter intelligence domestic service in 1910. The latter was headed by Sir Vernon Kell and was originally aimed at calming public fears of large scale German espionage.[24] As the Service was not authorized with police powers, Kell liaised extensively with the Special Branch of Scotland Yard (headed by Basil Thomson), and succeeded in disrupting the work of Indian revolutionaries collaborating with the Germans during the war.

In the 1890s Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish artillery captain in the French army, was twice falsely convicted of passing military secrets to the Germans. The case convulsed France regarding antisemitism, and xenophobia, for a decade until he was exonerated. It raised public awareness of the rapidly developing world of espionage.[25][26]

20th century

First World War

By the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 all the major powers had highly sophisticated structures in place for the training and handling of spies and for the processing of the intelligence information obtained through espionage. The figure and mystique of the spy had also developed considerably in the public eye. The Dreyfus Affair, which involved international espionage and treason, contributed much to public interest in espionage[27][28] from 1894 onwards.

The spy novel emerged as a distinct genre of fiction in the late 19th century; it dealt with themes such as colonial rivalry, the growing threat of conflict in Europe and the revolutionary and anarchist domestic threat. The "spy novel" was defined by The Riddle of the Sands (1903) by British author Robert Erskine Childers, which played on public fears of a German plan to invade Britain (an amateur spy uncovers the nefarious plot). In the wake of Childers's success there followed a flood of imitators, including William Le Queux and E. Phillips Oppenheim.

The first World War (1914–1918) saw the honing and refinement of modern espionage techniques as all the belligerent powers utilized their intelligence services to obtain military intelligence, to commit acts of sabotage and to carry out propaganda. As the progress of the war became static and armies dug down in trenches, the utility of cavalry reconnaissance became of very limited effectiveness.[29]

Information gathered at the battlefront from the interrogation of prisoners-of-war typically could give insight only into local enemy actions of limited duration. To obtain high-level information on an enemy's strategic intentions, its military capabilities and deployment required undercover spy rings operating deep in enemy territory. On the Western Front the advantage lay with the Western Allies, as for most of the war German armies occupied Belgium and parts of northern France amidst a large and disaffected native population that could be organized into collecting and transmitting vital intelligence.[29]

British and French intelligence services recruited Belgian or French refugees and infiltrated these agents behind enemy lines via the Netherlands – a neutral country. Many collaborators were then recruited from the local population, who were mainly driven by patriotism and hatred of the harsh German occupation. By the end of the war the Allies had set up over 250 networks, comprising more than 6,400 Belgian and French citizens. These rings concentrated on infiltrating the German railway network so that the Allies could receive advance warning of strategic troop and ammunition movements.[29]

In 1916 Walthère Dewé founded the Dame Blanche ("White Lady") network as an underground intelligence group,which became the most effective Allied spy ring in German-occupied Belgium. It supplied as much as 75% of the intelligence collected from occupied Belgium and northern France to the Allies. By the end of the war, its 1,300 agents covered all of occupied Belgium, northern France and, through a collaboration with Louise de Bettignies' network, occupied Luxembourg. The network was able to provide a crucial few days warning before the launch of the German 1918 Spring Offensive.[30]

German intelligence was only ever able to recruit a very small number of spies. These were trained at an academy run by the Kriegsnachrichtenstelle in Antwerp and headed by Elsbeth Schragmüller, known as "Fräulein Doktor". These agents were generally isolated and unable to rely on a large support network for the relaying of information. The most famous German spy was Margaretha Geertruida Zelle, a Dutch exotic dancer with the stage name Mata Hari. As a Dutch subject, she was able to cross national borders freely. In 1916, she was arrested and brought to London where she was interrogated at length by Sir Basil Thomson, Assistant Commissioner at New Scotland Yard. She eventually claimed to be working for French intelligence. In fact, she had entered German service from 1915, and sent her reports to the mission in the German embassy in Madrid.[31] In January 1917, the German military attaché in Madrid transmitted radio messages to Berlin describing the helpful activities of a German spy code-named H-21. French intelligence agents intercepted the messages and, from the information it contained, identified H-21 as Mata Hari. She was executed by firing squad on 15 October 1917.

German spies in Britain did not meet with much success – the German spy ring operating in Britain was successfully disrupted by MI5 under Vernon Kell on the day after the declaration of the war. Home Secretary, Reginald McKenna, announced that "within the last twenty-four hours no fewer than twenty-one spies, or suspected spies, have been arrested in various places all over the country, chiefly in important military or naval centres, some of them long known to the authorities to be spies",[32][33]

One exception was Jules C. Silber, who evaded MI5 investigations and obtained a position at the censor's office in 1914. Using mailed window envelopes that had already been stamped and cleared he was able to forward microfilm to Germany that contained increasingly important information. Silber was regularly promoted and ended up in the position of chief censor, which enabled him to analyze all suspect documents.[34]

The British economic blockade of Germany was made effective through the support of spy networks operating out of neutral Netherlands. Points of weakness in the naval blockade were determined by agents on the ground and relayed back to the Royal Navy. The blockade led to severe food deprivation in Germany and was a major cause in the collapse of the Central Powers war effort in 1918.[35]

Codebreaking

Two new methods for intelligence collection were developed over the course of the war – aerial reconnaissance and photography and the interception and decryption of radio signals.[35] The British rapidly built up great expertise in the newly emerging field of signals intelligence and codebreaking.

In 1911, a subcommittee of the Committee of Imperial Defence on cable communications concluded that in the event of war with Germany, German-owned submarine cables should be destroyed. On the night of 3 August 1914, the cable ship Alert located and cut Germany's five trans-Atlantic cables, which ran under the English Channel. Soon after, the six cables running between Britain and Germany were cut.[36] As an immediate consequence, there was a significant increase in messages sent via cables belonging to other countries, and by radio. These could now be intercepted, but codes and ciphers were naturally used to hide the meaning of the messages, and neither Britain nor Germany had any established organisations to decode and interpret the messages. At the start of the war, the navy had only one wireless station for intercepting messages, at Stockton. However, installations belonging to the Post Office and the Marconi Company, as well as private individuals who had access to radio equipment, began recording messages from Germany.[37]

Room 40, under Director of Naval Education Alfred Ewing, formed in October 1914, was the section in the British Admiralty most identified with the British crypto analysis effort during the war. The basis of Room 40 operations evolved around a German naval codebook, the Signalbuch der Kaiserlichen Marine (SKM), and around maps (containing coded squares), which were obtained from three different sources in the early months of the war. Alfred Ewing directed Room 40 until May 1917, when direct control passed to Captain (later Admiral) Reginald 'Blinker' Hall, assisted by William Milbourne James.[38]

A similar organization began in the Military Intelligence department of the War Office, which become known as MI1b, and Colonel Macdonagh proposed that the two organizations should work together, decoding messages concerning the Western Front in France. A sophisticated interception system (known as 'Y' service), together with the post office and Marconi receiving stations grew rapidly to the point it could intercept almost all official German messages.[37]

As the number of intercepted messages increased it became necessary to decide which were unimportant and should just be logged, and which should be passed on to Room 40. The German fleet was in the habit each day of wirelessing the exact position of each ship and giving regular position reports when at sea. It was possible to build up a precise picture of the normal operation of the High Seas Fleet, indeed to infer from the routes they chose where defensive minefields had been placed and where it was safe for ships to operate. Whenever a change to the normal pattern was seen, it immediately signalled that some operation was about to take place and a warning could be given. Detailed information about submarine movements was also available.[39]

Both the British and German interception services began to experiment with direction finding radio equipment at the start of 1915. Captain H. J. Round working for Marconi had been carrying out experiments for the army in France and Hall instructed him to build a direction finding system for the navy. Stations were built along the coast, and by May 1915 the Admiralty was able to track German submarines crossing the North Sea. Some of these stations also acted as 'Y' stations to collect German messages, but a new section was created within Room 40 to plot the positions of ships from the directional reports. No attempts were made by the German fleet to restrict its use of wireless until 1917, and then only in response to perceived British use of direction finding, not because it believed messages were being decoded.[40]

Room 40 played an important role in several naval engagements during the war, notably in detecting major German sorties into the North Sea that led to the battles of Dogger Bank and Jutland when the British fleet was sent out to intercept them. However its most important contribution was probably in decrypting the Zimmermann Telegram, a telegram from the German Foreign Office sent via Washington to its ambassador Heinrich von Eckardt in Mexico.

In the Telegram's plain text, Nigel de Grey and William Montgomery learned of the German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmermann's offer to Mexico to join the war as a German ally. The telegram was made public by the United States, which declared war on Germany on 6 April 1917. This event demonstrated how the course of a war could be changed by effective intelligence operations.[41]

Russian Revolution

The outbreak of revolution in Russia and the subsequent seizure of power by the Bolsheviks, a party deeply hostile towards the capitalist powers, was an important catalyst for the development of modern international espionage techniques. A key figure was Sidney Reilly, a Russian-born adventurer and secret agent employed by Scotland Yard and the Secret Intelligence Service. He set the standard for modern espionage, turning it from a gentleman's amateurish game to a ruthless and professional methodology for the achievement of military and political ends. Reilly's career culminated in an failed attempt to depose the Bolshevik Government and assassinate Vladimir Ilyich Lenin.[42]

Another pivotal figure was Sir Paul Dukes, arguably the first professional spy of the modern age.[43] Recruited personally by Mansfield Smith-Cumming to act as a secret agent in Imperial Russia, he set up elaborate plans to help prominent White Russians escape from Soviet prisons after the Revolution and smuggled hundreds of them into Finland. Known as the "Man of a Hundred Faces," Dukes continued his use of disguises, which aided him in assuming a number of identities and gained him access to numerous Bolshevik organizations. He successfully infiltrated the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the Comintern, and the political police, or CHEKA. Dukes also learned of the inner workings of the Politburo, and passed the information to British intelligence.

In the course of a few months, Dukes, Hill, and Reilly succeeded in infiltrating Lenin’s inner circle, and gaining access to the activities of the Cheka and the Communist International at the highest level. This helped to convince the government of the importance of a well-funded secret intelligence service in peace time as a key component in formulating foreign policy. Churchill argued that intercepted communications were more useful "as a means of forming a true judgment of public policy than any other source of knowledge at the disposal of the State."[44]

Second World War

Churchill's order to "set Europe ablaze," was undertaken by the British Secret Service or Secret Intelligence Service, who developed a plan to train spies and saboteurs. Eventually, this would become the SOE or Special Operations Executive, and to ultimately involve the United States in their training facilities. Sir William Stephenson, the senior British intelligence officer in the western hemisphere, suggested to President Franklin D. Roosevelt that William J. Donovan devise a plan for an intelligence network modeled after the British Secret Intelligence Service or MI6 and Special Operations Executive’s (SOE) framework. Accordingly, the first American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) agents in Canada were sent for training in a facility set up by Stephenson, with guidance from English intelligence instructors, who provided the OSS trainees with the knowledge needed to come back and train other OSS agents. Setting German-occupied Europe ablaze with sabotage and partisan resistance groups was the mission. Through covert special operations teams, operating under the new Special Operations Executive (SOE) and the OSS' Special Operations teams, these men would be infiltrated into those countries of German-occupied Europe to help organize local resistance groups and supply them with logistical support: weapons, clothing, food, money, and direct them in attacks against the Axis powers. Through subversion, sabotage, and the direction of local guerrilla forces, SOE British agents and OSS teams had the mission of infiltrating behind enemy lines and wreaked havoc on the German infrastructure, so much, that an untold number of men were required to keep this in check, and kept the Germans off balance continuously like the French maquis. They actively resisted the German occupation of France, as did the Greek People's Liberation Army (ELAS) partisans who were armed and fed by both the OSS and SOE during the German occupation of Greece.

Spies were trained in the United States after having been trained at facilities in the United States and around the world. A few training facilities were clustered around the Washington, DC area and have been extensively studied and written by Chambers.[45] Prince William Forest Park was the site of an OSS training camp that operated from 1942 to 1945. Area "C" was used extensively for communications training, whereas Area "A" was used for training some of the OGs, or Operational Groups. Catoctin Mountain Park, now the location of Camp David, was the site of OSS training Area "B." The well-known resting place for US congressman, the Congressional Country Club (Area F) in Bethesda, Maryland, was the main OSS training facility. The primary OSS training camps overseas were set up initially in Great Britain, French Algeria, Egypt, and in southern Italy. In the Far East, OSS training facilities were set up in India, Ceylon, and China. The OSS' Mediterranean training center in Cairo, Egypt, known to many as the "Spy School," was modeled after the SOE's training facility STS 102 in Haifa, then Palestine.[46] It had once been a lavish palace of King Farouk's brother-in-law.[47] Americans whose heritage stemmed from Italy, Yugoslavia, and Greece were trained at Cairo's "Spy School." Secret Intelligence (SI), Special Operations (SO), and Morale Operations (MO) agents from here were also sent for parachute training at the SOE's STS 102 Ramat David camp outside Haifa. John Vassos, the well-known industrial designer for the RCA Corporation, was the Commanding Officer of OSS' Cairo's Spy School during World War II. Under Vassos' leadership, spies were trained and sent on missions behind enemy lines: primarily to Greece, the Balkans, and Italy. Morse code and encryption lessons were taught by the SOE to these OSS agents at the SOE's STS 102 training facility at Mount Carmel outside Haifa, as well as weapons, commando, and defensive-type training.[48][49][50] After completion of their spy training, these agents — many of whom were of Yugoslavian, Greek, or Italian descent — were sent back on missions to the Balkans and Italy where their accents would not pose a problem for their assimilation.[51][52] Informants were common in World War II. In November 1939, the German Hans Ferdinand Mayer sent what is called the Oslo Report to inform the British of German technology and projects in an effort to undermine the Nazi regime. The Réseau AGIR was a French network developed after the fall of France that reported the start of construction of V-weapon installations in Occupied France to the British.

Counterespionage included the use of turned Double Cross agents to misinform Nazi Germany of impact points during the Blitz and internment of Japanese in the US against "Japan's wartime spy program". Additional WWII espionage examples include Soviet spying on the US Manhattan project, the German Duquesne Spy Ring convicted in the US, and the Soviet Red Orchestra spying on Nazi Germany. The US lacked a specific agency at the start of the war, but quickly formed the Office of Strategic Services (OSS).

Since the 19th century new approaches have included professional police organizations, the police state and geopolitics. New intelligence methods have emerged, most recently imagery intelligence, signals intelligence, cryptanalysis and spy satellites.

Cold War

Post-Cold War

Counter-terrorism

Israel

In Israel, the Shin Bet unit is the agency for homeland security and counter intelligence. The department for secret and confidential counter terrorist operations is called Kidon.[53] It is part of the national intelligence agency Mossad and can also operate in other capacities.[53] Kidon was described as "an elite group of expert assassins who operate under the Caesarea branch of the espionage organization." The unit only recruits from "former soldiers from the elite IDF special force units."[54] There is almost no reliable information available on this ultra-secret organisation.

See also

References

- ^ "Espionage in Ancient Rome". HistoryNet.

- ^ Aladashvili, Besik (2017). Fearless: A Fascinating Story of Secret Medieval Spies.

- ^ Soustelle, Jacques (2002). The Daily Life of the Aztecas. Phoenix Press. p. 209. ISBN 1-84212-508-7.

- ^ "Henrywotton.org.uk". Henrywotton.org.uk. Retrieved 2012-07-07.

- ^ a b c d e Hutchinson, Robert (2007) Elizabeth's Spy Master: Francis Walsingham and the Secret War that Saved England. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-84613-0. pp. 84–121

- ^ Wilson, pp. 94, 100–101, 142

- ^ Philip H.J. Davies (2012). Intelligence and Government in Britain and the United States: A Comparative Perspective. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781440802812.

- ^ Edwin C. Fishel, "Pinkerton and McClellan: Who Deceived Whom?." Civil War History 34.2 (1988): 115-142. Excerpt

- ^ James Mackay, Allan Pinkerton: The First Private Eye (1996) downplays the exaggeration.

- ^ E.C. Fishel, The Secret War for The Union: The Untold Story of Military Intelligence in the Civil War (1996) .

- ^ Harnett, Kane T. (1954). Spies for the Blue and the Gray. Hanover House. pp. 27–29.

- ^ Markle, Donald E. (1994). Spies and Spymasters of the Civil War. Hippocrene Books. p. 2. ISBN 078180227X.

- ^ John Keegan, Intelligence in War: The value--and limitations--of what the military can learn about the enemy (2004) pp 78-98

- ^ Warren C. Robinson (2007). Jeb Stuart and the Confederate Defeat at Gettysburg. U of Nebraska Press. pp. 38, 124–29, quoting p 129.

- ^ Thomas G. Fergusson (1984). British Military Intelligence, 1870–1914: The Development of a Modern Intelligence Organization. University Publications of America. p. 45. ISBN 9780890935415.

- ^ a b Anciens des Services Spéciaux de la Défense Nationale ( France )

- ^ "Espionage".

- ^ Dorril, Stephen (2002). MI6: Inside the Covert World of Her Majesty's Secret Intelligence Service. Simon & Schuster. p. 137. ISBN 0-7432-1778-0.

- ^ "A Short History of Army Intelligence" (PDF). Michael E. Bigelow (Command Historian, United States Army Intelligence and Security Command. 2012. p. 10.

- ^ Calder Walton (2013). Empire of Secrets: British Intelligence, the Cold War, and the Twilight of Empire. Overlook. pp. 5–6. ISBN 9781468310436.

- ^ "Okhrana" literally means "the guard"

- ^ Okhrana Britannica Online

- ^ Ian D. Thatcher, Late Imperial Russia: problems and prospects, page 50

- ^ Christopher Andrew, The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of Mi5 (London, 2009), p.21.

- ^ Douglas Porch, The French Secret Services: From the Dreyfus Affair to the Gulf War (1995).

- ^ Allan Mitchell, "The Xenophobic Style: French Counterespionage and the Emergence of the Dreyfus Affair." Journal of Modern History 52.3 (1980): 414-425. online

- ^ Cook, Chris. Dictionary of Historical Terms (1983) p. 95.

- ^ Miller, Toby. Spyscreen: Espionage on Film and TV from the 1930s to the 1960s Oxford University Press, 2003 ISBN 0-19-815952-8 p. 40-41

- ^ a b c "Espionage". International Encyclopedia of the First World War (WW1).

- ^ "Walthère Dewé". Les malles ont une mémoire 14–18. Retrieved 2014-04-09.

- ^ Adams, Jefferson (2009). Historical Dictionary of German Intelligence. Rowman&Littlefield. p. 290. ISBN 978-0-8108-5543-4.

- ^ Hansard, HC 5ser vol 65 col 1986.

- ^ Christopher Andrew, "The Defence of the Realm: The Authorised History of MI5", Allen Lane, 2009, pp. 49–52.

- ^ Jules C. Silber, The Invisible Weapons, Hutchinson, 1932, Londres, D639S8S5.

- ^ a b Douglas L. Wheeler. "A Guide to the History of Intelligence 1800–1918" (PDF). Journal of U.S. Intelligence Studies.

- ^ Winkler 2009, pp. 848–849.

- ^ a b Beesly, Patrick (1982). Room 40: British Naval Intelligence, 1914–1918. Long Acre, London: Hamish Hamilton Ltd. pp. 2–14. ISBN 0-241-10864-0.

- ^ Johnson 1997, pp. 32.

- ^ Denniston, Robin (2007). Thirty secret years: A.G. Denniston's work for signals intelligence 1914–1944. Polperro Heritage Press. ISBN 0-9553648-0-9.

- ^ Johnson, John (1997). The Evolution of British Sigint, 1653–1939. London: H.M.S.O.

- ^ Tuchman, Barbara W. (1958). The Zimmermann Telegram. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-32425-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Richard B. Spence, Trust No One: The Secret World Of Sidney Reilly; 2002, Feral House, ISBN 0-922915-79-2.

- ^ "These Are the Guys Who Invented Modern Espionage". History News Network.

- ^ Michael I. Handel (2012). Leaders and Intelligence. Routledge. p. 188. ISBN 9781136287169.

- ^ https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/oss/

- ^ https://books.google.com/books?id=9euhPIt-d2oC&pg=PA1&lpg=PA1&dq=%22spy+school%22+and+oss+and+egypt&source=bl&ots=FDJ0tlpu_5&sig=aGlWnqm6qhTusuylL8UNfLRRsYk&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjBu6WSmeLSAhVkxoMKHUhNDoYQ6AEIGjAA#v=onepage&q=%22spy%20school%22%20and%20oss%20and%20egypt&f=false

- ^ https://books.google.com/books?id=vkGtBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA99&lpg=PA99&dq=OSS+and+king+farouk&source=bl&ots=bbjJDTuZq3&sig=uSffPI3d8U9reYiK9Kggmn5tDe8&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwirs8vx2N7SAhXB1IMKHRJzAfQQ6AEILTAH#v=onepage&q=OSS%20and%20king%20farouk&f=false

- ^ https://books.google.com/books?id=S1ekCAAAQBAJ&pg=PT67&lpg=PT67&dq=sts+and+102+and+SOE&source=bl&ots=8Y2LQMISXF&sig=uaMuaEIytufBmOAPQOpggCSgY5g&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjPnp6rvuTSAhUI4oMKHTknD5AQ6AEINjAF#v=onepage&q=sts%20and%20102%20and%20SOE&f=false

- ^ https://books.google.com/books?id=9euhPIt-d2oC&pg=PA54&lpg=PA54&dq=SOE+haifa+parachute+training+doundoulakis&source=bl&ots=FDJ0ppqpY9&sig=5eHQW8ibsycZqK8NYTsK_6aVf4g&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj71ZPs3dfSAhWs7oMKHfNuDgUQ6AEIHzAB#v=onepage&q=SOE%20haifa%20parachute%20training%20doundoulakis&f=false

- ^ https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/oss/chap8.pdf

- ^ http://www.smithsonianchannel.com/videos/how-to-lie-for-your-life/34349

- ^ https://books.google.com/books?id=kp7mDiMJ0W0C&pg=PT99&lpg=PT99&dq=training+facility+cairo+egypt+oss&source=bl&ots=a6VzCjNtpi&sig=BfB5fiwgysiETI_zYOWxq0HSdGY&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjXu6X03NbSAhVC9IMKHZAJAQUQ6AEIIjAB#v=onepage&q=training%20facility%20cairo%20egypt%20oss&f=false

- ^ a b Melman, Yossi (19 February 2010). "Kidon, the Mossad within the Mossad". Haaretz. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ^ Yaakov Katz Israel Vs. Iran: The Shadow War, Potomac Books, Inc, 2012, page 91, By Yaakov Katz, Yoaz Hendel

Further reading

- Andrew, Christopher. The Secret World: A History of Intelligence (2018) 940pp. covers ancient history to present

- Bauer, Deborah Susan. Marianne is Watching: Knowledge, Secrecy, Intelligence and the Origins of the French Surveillance State (1870-1914). (PhD Dissertation, UCLA, 2013.) Online Bibliography pp 536-59

- Becket, Henry S. A. Dictionary of Espionage: Spookspeak into English (1986)' covers 2000 terms

- Besik, Aladashvili. Fearless: A Fascinating Story of Secret Medieval Spies (2017) [excerpt

- Buranelli, Vincent, and Nan Buranelli. Spy Counterspy an Encyclopedia of Espionage (1982), 360pp

- Burton, Bob. Dictionary of Espionage and Intelligence (2014) 800+ terms used in international and covert espionage

- Deacon, Richard. The French Secret Service (1990).

- Friedman, George. America's Secret War: Inside the Hidden Worldwide Struggle Between the United States and Its Enemies 2005

- Jackson, Peter. France and the Nazi Menace: Intelligence and Policy Making, 1933-1939 (2000).

- Jeffreys-Jones, Rhodri. In Spies We Trust: The Story of Western Intelligence (2013), covers U.S. and Britain

- Jeffreys-Jones, Rhodri. American Espionage: From Secret Service to CIA (2nd ed 2017) online free to borrow

- Johnson, Robert. Spying for Empire: The Great Game in Central and South Asia, 1757–1947 London: Greenhill 2006

- Kahn, David. The Codebreakers: The Comprehensive History of Secret Communication from Ancient Times to the Internet (2nd ed. 1996)

- Keegan, John. Intelligence In War: Knowledge of the Enemy from Napoleon to Al-Qaeda (2003)

- Knightley, Philip The Second Oldest Profession: Spies and Spying in the Twentieth Century (1986).

- Lerner, Brenda Wilmoth & K. Lee Lerner, eds. Terrorism: essential primary sources Thomas Gale 2006 ISBN 978-1-4144-0621-3

- Lerner, K. Lee and Brenda Wilmoth Lerner, eds. Encyclopedia of Espionage, Intelligence and Security (3 vol. 2003) 1100 pages, 800 entries

- May, Ernest R. ed. Knowing One's Enemies: Intelligence Assessment Before the Two World Wars (1984).

- Murray, Williamson, and Allan Reed Millett, eds. Calculations: net assessment and the coming of World War II (1992).

- O'Toole, G. J. A. Honorable Treachery: A History of U.S. Intelligence, Espionage, Covert Action from the American Revolution to the CIA (1991) online free to borrow

- O'Toole, G. J. A. The Encyclopedia of American Intelligence and Espionage: From the Revolutionary War to the Present (1988)

- Owen, David. Hidden Secrets: A Complete History of Espionage and the Technology Used to Support It

- Polmar, Norman, and Thomas Allen. Spy Book: The Encyclopedia of Espionage (2nd ed. 2004) 752pp 2000+ entries online freee to borrow

- Porch, Douglas. The French Secret Services: A History of French Intelligence from the Dreyfus Affair to the Gulf War (2003).

- Richelson, Jeffery T. A Century of Spies: Intelligence in the Twentieth Century (1977)

- Richelson, Jeffery T. The U.S. Intelligence Community 1999 fourth edition

- Smith Jr., W. Thomas. Encyclopedia of the Central Intelligence Agency (2003).

- Trahair, Richard and Robert L. Miller. Encyclopedia of Cold War Espionage, Spies, and Secret Operations (2nd ed. 2004) 572pp; 300+ entries

- Tuchman, Barbara W. The Zimmermann Telegram (1966) Germany and U.S. in 1917

- Warner, Michael. The Rise and Fall of Intelligence: An International Security History (2014)

- West, Nigel. MI6: British Secret Intelligence Service Operations 1909–1945 1983