Japanese entry into World War I: Difference between revisions

→Background: copy ex "Anglo-Japanese Alliance" |

|||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

==Background== |

==Background== |

||

{{Further|Anglo-Japanese Alliance}} |

|||

[[File:Naval-race-1909.jpg|thumb|290px|right|1909 cartoon in the English magazine ''Puck'' shows (clockwise) US, Germany, Britain, France and Japan engaged in naval race in a "no limit" game.]] |

[[File:Naval-race-1909.jpg|thumb|290px|right|1909 cartoon in the English magazine ''Puck'' shows (clockwise) US, Germany, Britain, France and Japan engaged in naval race in a "no limit" game.]] |

||

Japan and Great Britain had both avoided military alliances before 1900. That changed in 1902 with the signing of a treaty. It was a diplomatic milestone that saw an end to Britain's [[splendid isolation]], the alliance was renewed and expanded in scope twice, in 1905 and 1911. The United States disliked the treaty and it was officially terminated in 1923. The original goal was opposition to Russian expansion. The alliance facilitated Japanese entry into the World War, but did not require Japan to do so.<ref>Phillips Payson O'Brien, [https://books.google.com/books?id=LNbDqOzSvpkC&dq=The+Anglo-Japanese+Alliance,+1902-1922&source=gbs_summary_s&cad=0 ''The Anglo-Japanese Alliance, 1902-1922.'' (2004).]</ref> |

|||

==Operations against Germany== |

==Operations against Germany== |

||

Revision as of 02:18, 31 July 2018

Japan entered the war on the side of the Allies on 23 August 1914, seizing the opportunity of Germany's distraction with the European War to expand its sphere of influence in China and the Pacific. There was minimal fighting. Japan already had a military alliance with Britain, but that did not obligate it to enter the war. It joined the Allies in order to make territorial gains. It acquired Germany's scattered small holdings in the Pacific and on the China coast. The other Allies pushed back hard against Japan's efforts to dominate China through the Twenty-One Demands of 1915. Japan's occupation of Siberia against the Bolsheviks proved unproductive. Japan's wartime diplomacy and limited military action had produced few results, and at the Paris Versailles peace conference. at the end of the war, Japan was largely frustrated in its ambitions.

Background

Japan and Great Britain had both avoided military alliances before 1900. That changed in 1902 with the signing of a treaty. It was a diplomatic milestone that saw an end to Britain's splendid isolation, the alliance was renewed and expanded in scope twice, in 1905 and 1911. The United States disliked the treaty and it was officially terminated in 1923. The original goal was opposition to Russian expansion. The alliance facilitated Japanese entry into the World War, but did not require Japan to do so.[1]

Operations against Germany

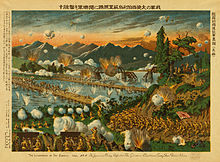

The onset of the First World War in Europe eventually showed how far German–Japanese relations had truly deteriorated. On 7 August 1914, only three days after Britain declared war on the German Empire, the Japanese government received an official request from the British government for assistance in destroying the German raiders of the Kaiserliche Marine in and around Chinese waters. Japan, eager to reduce the presence of European colonial powers in South-East Asia, especially on China's coast, sent Germany an ultimatum on 14 August 1914, which was left unanswered. Japan then formally declared war on the German Empire on 23 August 1914 thereby entering the First World War as an ally of Britain, France and the Russian Empire to seize the German-held Caroline, Marshall, and Mariana Islands in the Pacific.

The only major battle that took place between Japan and Germany was the siege of the German-controlled Chinese port of Tsingtao in Kiautschou Bay. The German forces held out from August until November 1914, under a total Japanese/British blockade, sustained artillery barrages and manpower odds of 6:1 – a fact that gave a morale boost during the siege as well as later in defeat. After Japanese troops stormed the city, the German dead were buried at Tsingtao and the remaining troops were transported to Japan where they were treated with respect at places like the Bandō Prisoner of War camp.[2] In 1919, when the German Empire formally signed the Treaty of Versailles, all prisoners of war were set free and returned to Europe.

Japan was a signatory of the Treaty of Versailles, which stipulated harsh repercussions for Germany. In the Pacific, Japan gained Germany's islands north of the equator (the Marshall Islands, the Carolines, the Marianas, the Palau Islands) and Kiautschou/Tsingtao in China.[3] Article 156 of the Treaty also transferred German concessions in Shandong to Japan rather than returning sovereign authority to the Republic of China, an issue soon to be known as Shandong Problem. Chinese outrage over this provision led to demonstrations, and a cultural movement known as the May Fourth Movement influenced China not to sign the treaty. China declared the end of its war against Germany in September 1919 and signed a separate treaty with Germany in 1921. This fact greatly contributed to Germany relying on China, and not Japan, as its strategic partner in East Asia for the coming years.[4]

Operations against China

Japanese and British military forces in 1914 liquidated Germany's holdings in China. Japan occupied the German military colony in Qingdao, and occupied portions of Shandong Province. China was financially chaotic, highly unstable politically, and militarily very weak. Its best hope was to attend the postwar peace conference, and hope to find friends would help block the threats of Japanese expansion. China declared war on Germany in August 1917 as a technicality to make it eligible to attend the postwar peace conference. They planned to send a combat unit to the Western Front, but never did so.[5][6] British diplomats were afraid that the U.S. and Japan would displace Britain's leadership role in the Chinese economy. They sought to play Japan and the United States against each other, while at the same time maintaining cooperation among all three nations against Germany.[7]

In January 1915, Japan secretly issued an ultimatum of Twenty-One Demands to the Chinese government. They included Japanese control of former German rights, 99 year leases in southern Manchuria, an interest in steel mills, and concessions regarding railways. China did have a seat at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. However it was refused a return of the former German concessions and China had to accept the Twenty-One demands. A major reaction to this humiliation was a surge in Chinese nationalism expressed in the May Fourth Movement.[8]

Results

Japan's participation in World War I on the side of the Allies sparked unprecedented economic growth and earned Japan new colonies in the South Pacific seized from Germany.[9] After the war Japan signed the Treaty of Versailles and enjoyed good international relations through its membership in the League of Nations and participation in international disarmament conferences.[10]

See also

- Causes of World War I

- Diplomatic history of World War I

- Historiography of the causes of World War I

- History of China–Japan relations

- History of Japanese foreign relations

- International relations of the Great Powers (1814–1919)

- Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905

Notes

- ^ Phillips Payson O'Brien, The Anglo-Japanese Alliance, 1902-1922. (2004).

- ^ Schultz-Naumann, p. 207. The Naruto camp orchestra (enlarged from the band of the III. Seebatallion) gave Beethoven and Bach concerts throughout Japan wearing their uniforms

- ^ Louis (1967), pp. 117–130

- ^ Sun Yat-sen. The International Development of China page 298. China Cultural Service, Taipei, 1953

- ^ Stephen G. Craft, "Angling for an Invitation to Paris: China's Entry into the First World War". International History Review 16#1 (1994): 1–24.

- ^ Guoqi Xu, "The Great War and China's military expedition plan". Journal of Military History 72#1 (2008): 105–140.

- ^ Clarence B. Davis, "Limits of Effacement: Britain and the Problem of American Cooperation and Competition in China, 1915–1917". Pacific Historical Review 48#1 (1979): 47–63. in JSTOR

- ^ Zhitian Luo, "National humiliation and national assertion-The Chinese response to the twenty-one demands" Modern Asian Studies (1993) 27#2 pp 297–319.

- ^ Totman, 471, 488–489.

- ^ Henshall, 111.

Further reading

- Akagi, Roy Hidemichi. Japan's Foreign Relations 1542-1936: A Short History (1936) online 560pp

- Barnhart, Michael A. Japan and the World since 1868 (1995) excerpt

- Beasley, William G. Japanese Imperialism, 1894–1945 (Oxford UP, 1987).

- Dickinson, Frederick R. War and National Reinvention: Japan in the Great War, 1914-1919 (1999).

- Drea, Edward J. Japan's Imperial Army: Its Rise and Fall, 1853–1945 (2016) online

- Duus, Peter, ed. The Cambridge history of Japan: The twentieth century (vol 6 1989)

- Edgerton, Robert B., Warriors of the Rising Sun: A History of the Japanese Military (New York: Norton, 1997)

- Henshall, Kenneth. A History of Japan: From Stone Age to Superpower (2012)

- Inoguchi, Takashi. Japan's Foreign Policy in an Era of Global Change (2013).

- Iriye, Akira. Japan and the wider world: from the mid-nineteenth century to the present (1997).

- Jansen, Marius B. Japan and China: From War to Peace, 1894-1972 (1975)

- Kibata, Y. and I. Nish, eds. The History of Anglo-Japanese Relations, 1600-2000: Volume I: The Political-Diplomatic Dimension, 1600-1930 (2000) excerpt, first of five topical volumes also covering social, economic and military relations between Japan and Great Britain.

- Kowner, Rotem. The Impact of the Russo–Japanese War (2007).

- Matray, James I. Japan's Emergence as a Global Power (2001) online at Questia

- Morley, James William, ed. Japan's foreign policy, 1868-1941: a research guide (Columbia UP, 1974), Chapters by international experts who cover military policy, economic policy, cultural policy, and relations with Britain, China, Germany, Russia, and the United States; 635pp

- Nish, Ian. Japanese Foreign Policy, 1869-1942: Kasumigaseki to Miyakezaka (1977)

- Nish, Ian. Japanese Foreign Policy in the Interwar Period (2002) covers 1912-1946 online

- Nish, Ian. "An Overview of Relations between China and Japan, 1895–1945." China Quarterly (1990) 124: 601-623. online

- O'Brien, Phillips Payson. The Anglo-Japanese Alliance, 1902-1922 (2004).

- Paine, S.C.M. The Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895: Perceptions, Power, and Primacy (2003)

- Sansom, George Bailey. The Western World and Japan, a Study in the Interaction of European and Asiatic Cultures. (1974)

- Storry, Richard. Japan and the Decline of the West in Asia, 1894–1943 (1979)

- Shimamoto, Mayako, Koji Ito and Yoneyuki Sugita, eds. Historical Dictionary of Japanese Foreign Policy (2015) excerpt

- Strachan, Hew. The First World War. 1 - To Arms (Oxford UP, 2003).

- Totman, Conrad (2005). A History of Japan. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-119-02235-0.

Primary sources

- Albertini

- Beasley, W. G. ed. Select Documents on Japanese Foreign Policy 1853-1868 (1960) online

- Morley, James W. ed. Japan's Foreign Policy, 1868-1941: A Research Guide (1974) 618pp