Kingdom of Georgia: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 104: | Line 104: | ||

== Background == |

== Background == |

||

{{Main|Arab rule in Georgia}}During the [[Classical antiquity|classical era]], several independent kingdoms established in what is now Georgia, such as [[Colchis]], later known as [[Lazica]] and [[Caucasian Iberia|Iberia]]. The Georgians [[Christianization of Iberia|adopted Christianity]] in the early 4th century, giving a great stimulus to the development of literature, arts, and ultimately playing a key role in the further formation of the unified Georgian nation. |

{{Main|Arab rule in Georgia}}During the [[Classical antiquity|classical era]], several independent kingdoms were established in what is now Georgia, such as [[Colchis]], later known as [[Lazica]] and [[Caucasian Iberia|Iberia]]. The Georgians [[Christianization of Iberia|adopted Christianity]] in the early 4th century, giving a great stimulus to the development of literature, arts, and ultimately playing a key role in the further formation of the unified Georgian nation. |

||

Located on the crossroads of protracted [[Roman–Persian Wars|Roman–Persian wars]], the early Georgian kingdoms disintegrated into various feudal regions by the early [[Middle Ages]]. This made it easy for the remaining Georgian realms to fall prey to the [[Arab rule in Georgia|early Muslim conquests]] in the 7th century. After the wide political and cultural changes brought about by the Muslim conquests, refugees from the Iberia took shelter in the West, either in [[Kingdom of Abkhazia|Abkhazia]] or [[Principality of Tao-Klarjeti|Tao-Klarjeti]], and brought there their culture. |

Located on the crossroads of protracted [[Roman–Persian Wars|Roman–Persian wars]], the early Georgian kingdoms disintegrated into various feudal regions by the early [[Middle Ages]]. This made it easy for the remaining Georgian realms to fall prey to the [[Arab rule in Georgia|early Muslim conquests]] in the 7th century. After the wide political and cultural changes brought about by the Muslim conquests, refugees from the Iberia took shelter in the West, either in [[Kingdom of Abkhazia|Abkhazia]] or [[Principality of Tao-Klarjeti|Tao-Klarjeti]], and brought there their culture. |

||

In struggle against the [[Arab rule in Georgia|Arab occupation]], [[Bagrationi dynasty]] came to rule over [[Tao-Klarjeti (historical region)|Tao-Klarjeti]], former southern provinces of Iberia, and established [[Principality of Tao-Klarjeti|Kouropalatate of Iberia]] as a nominal vassal of the Byzantine Empire. The restoration of the Iberian kingship begins in 888, when [[Adarnase IV of Iberia]] took the title of "[[List of monarchs of Georgia#Kings of Iberia|King of Iberia]]". However, the Bagrationi dynasty failed to maintain the integrity of their kingdom, which was actually divided between the two branches of the family with the main branch retaining [[Tao (historical region)|Tao]] and another controlling [[Klarjeti]]. |

In struggle against the [[Arab rule in Georgia|Arab occupation]], [[Bagrationi dynasty]] came to rule over [[Tao-Klarjeti (historical region)|Tao-Klarjeti]], former southern provinces of Iberia, and established [[Principality of Tao-Klarjeti|Kouropalatate of Iberia]] as a nominal vassal of the Byzantine Empire. The restoration of the Iberian kingship begins in 888, when [[Adarnase IV of Iberia]] took the title of "[[List of monarchs of Georgia#Kings of Iberia|King of Iberia]]". However, the Bagrationi dynasty failed to maintain the integrity of their kingdom, which was actually divided between the two branches of the family with the main branch retaining in [[Tao (historical region)|Tao]] and another controlling [[Klarjeti]]. |

||

An [[Marwan ibn Muhammad's invasion of Georgia|Arab incursion]] into western Georgia was repelled by [[Abasgoi|Abasgians]] jointly with [[Lazica|Lazic]] and [[Principality of Iberia|Iberian]] allies in 736, towards {{Circa}}786, [[Leon II of Abkhazia|Leon II]] won his full independence from [[Byzantine Empire|Byzantine]] and transferred his capital to the western Georgian city of [[Kutaisi]] unifying Lazica and Abasgia via a dynastic union. The increasingly expansionist tendencies of the kingdom led to the enlargement of its realm to the east. In 9th century western Georgian Church broke away from [[Constantinople]] and recognized the authority of the [[List of heads of the Georgian Orthodox Church#Catholicoi of Kartli (467–1010)|Catholicate of Mtskheta]]; language of the church in Abkhazia shifted from [[Greek language|Greek]] to [[Georgian language|Georgian]], as Byzantine power decreased and doctrinal differences disappeared.<ref>{{harvnb|Rapp|2007|p=145}}</ref> It is not accidental that the process of unification of Georgia in a single feudal kingdom began with the struggle of the Abkhazian principality against Byzantium, fighting for hegemony within the Georgian territories. |

An [[Marwan ibn Muhammad's invasion of Georgia|Arab incursion]] into western Georgia was repelled by [[Abasgoi|Abasgians]] jointly with [[Lazica|Lazic]] and [[Principality of Iberia|Iberian]] allies in 736, towards {{Circa}}786, [[Leon II of Abkhazia|Leon II]] won his full independence from [[Byzantine Empire|Byzantine]] and transferred his capital to the western Georgian city of [[Kutaisi]], thus unifying Lazica and Abasgia via a dynastic union. The increasingly expansionist tendencies of the kingdom led to the enlargement of its realm to the east. In 9th century western Georgian Church broke away from [[Constantinople]] and recognized the authority of the [[List of heads of the Georgian Orthodox Church#Catholicoi of Kartli (467–1010)|Catholicate of Mtskheta]]; language of the church in Abkhazia shifted from [[Greek language|Greek]] to [[Georgian language|Georgian]], as Byzantine power decreased and doctrinal differences disappeared.<ref>{{harvnb|Rapp|2007|p=145}}</ref> It is not accidental that the process of unification of Georgia in a single feudal kingdom began with the struggle of the Abkhazian principality against Byzantium, fighting for hegemony within the Georgian territories. |

||

== Unification of the Georgian State == |

== Unification of the Georgian State == |

||

| Line 118: | Line 118: | ||

== War and peace with Byzantium == |

== War and peace with Byzantium == |

||

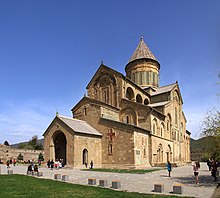

{{Main|Byzantine–Georgian wars}}The major political and military event during [[George I of Georgia|George I]]’s reign, a war against the [[Byzantine Empire]], had its roots back to the 990s, when the Georgian prince [[David III of Tao|David III]] of Tao, following his abortive rebellion against Emperor [[Basil II]], had to agree to cede his extensive possessions in [[Tao (historical region)|Tao]] to the emperor on his death. All the efforts by David’s stepson and George’s father, [[Bagrat III of Georgia|Bagrat III]], to prevent these territories from being annexed to the empire went in vain. Young and ambitious, George [[David III of Tao#Wars of the Kuropalates’ succession|launched a campaign]] to restore the Curopalates’ succession to Georgia and [[Battle of Shirimni|occupied Tao]] in 1015–1016. Byzantines were at that time involved in a relentless war with the [[First Bulgarian Empire|Bulgar Empire]], limiting their actions to the west. But as soon as [[Byzantine conquest of Bulgaria|Bulgaria was conquered]], Basil II led his army against Georgia (1021). An exhausting war lasted for two years, and ended in a [[Battle of Svindax|decisive Byzantine victory]], forcing George to agree to a peace treaty, in which he had not only to abandon his claims to Tao, but to surrender several of his southwestern possessions, later reorganized into [[Iberia (theme)|theme of Iberia]], to Basil and to give his three-year-old son, [[Bagrat IV of Georgia|Bagrat IV]], as hostage.[[File:Svetitskhoveli_Cathedral_in_Georgia,_Europe.jpg|link=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Svetitskhoveli_Cathedral_in_Georgia,_Europe.jpg|thumb|The construction of [[Svetitskhoveli]]Cathedral in [[Mtskheta]], now a [[UNESCO]] [[World Heritage Site]], was initiated in the 1020s by George I.]]The young child Bagrat IV spent the next three years in the imperial capital of [[Constantinople]] and was released in 1025. After George I's death in 1027, Bagrat, aged eight, succeeded to the throne. By the time Bagrat IV became king, the Bagratids’ drive to complete the unification of all Georgian lands had gained irreversible momentum. The kings of Georgia sat at [[Kutaisi]] in western Georgia from which they ran all of what had been the [[Kingdom of Abkhazia]] and a greater portion of [[Kingdom of Iberia|Iberia]]; [[Tao (historical region)|Tao]] had been lost to the Byzantines while a [[Muslim]] emir [[Emirate of Tbilisi|remained in Tbilisi]] and the kings of [[Kingdom of Kakheti-Hereti|Kakheti-Hereti]] obstinately defended their autonomy in easternmost Georgia. Furthermore, the loyalty of great nobles to the Georgian crown was far from stable. During Bagrat’s minority, the [[Liparit IV, Duke of Kldekari|regency]] had advanced the positions of the high nobility whose influence he subsequently [[Battle of Sasireti|tried to limit]] when he assumed full ruling powers. Simultaneously, the Georgian crown was confronted with two formidable external foes: the Byzantine Empire and the resurgent [[Seljuq dynasty|Seljuq Turks]]. |

{{Main|Byzantine–Georgian wars}}[[File:Map_Byzantine_Empire_1045.svg|thumb|220x220px|Georgia during the Byzantine Empire, 1045 AD]]The major political and military event during [[George I of Georgia|George I]]’s reign, a war against the [[Byzantine Empire]], had its roots back to the 990s, when the Georgian prince [[David III of Tao|David III]] of Tao, following his abortive rebellion against Emperor [[Basil II]], had to agree to cede his extensive possessions in [[Tao (historical region)|Tao]] to the emperor on his death. All the efforts by David’s stepson and George’s father, [[Bagrat III of Georgia|Bagrat III]], to prevent these territories from being annexed to the empire went in vain. Young and ambitious, George [[David III of Tao#Wars of the Kuropalates’ succession|launched a campaign]] to restore the Curopalates’ succession to Georgia and [[Battle of Shirimni|occupied Tao]] in 1015–1016. Byzantines were at that time involved in a relentless war with the [[First Bulgarian Empire|Bulgar Empire]], limiting their actions to the west. But as soon as [[Byzantine conquest of Bulgaria|Bulgaria was conquered]], Basil II led his army against Georgia (1021). An exhausting war lasted for two years, and ended in a [[Battle of Svindax|decisive Byzantine victory]], forcing George to agree to a peace treaty, in which he had not only to abandon his claims to Tao, but to surrender several of his southwestern possessions, later reorganized into [[Iberia (theme)|theme of Iberia]], to Basil and to give his three-year-old son, [[Bagrat IV of Georgia|Bagrat IV]], as hostage.[[File:Svetitskhoveli_Cathedral_in_Georgia,_Europe.jpg|link=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Svetitskhoveli_Cathedral_in_Georgia,_Europe.jpg|thumb|The construction of [[Svetitskhoveli]]Cathedral in [[Mtskheta]], now a [[UNESCO]] [[World Heritage Site]], was initiated in the 1020s by George I.]]The young child Bagrat IV spent the next three years in the imperial capital of [[Constantinople]] and was released in 1025. After George I's death in 1027, Bagrat, aged eight, succeeded to the throne. By the time Bagrat IV became king, the Bagratids’ drive to complete the unification of all Georgian lands had gained irreversible momentum. The kings of Georgia sat at [[Kutaisi]] in western Georgia from which they ran all of what had been the [[Kingdom of Abkhazia]] and a greater portion of [[Kingdom of Iberia|Iberia]]; [[Tao (historical region)|Tao]] had been lost to the Byzantines while a [[Muslim]] emir [[Emirate of Tbilisi|remained in Tbilisi]] and the kings of [[Kingdom of Kakheti-Hereti|Kakheti-Hereti]] obstinately defended their autonomy in easternmost Georgia. Furthermore, the loyalty of great nobles to the Georgian crown was far from stable. During Bagrat’s minority, the [[Liparit IV, Duke of Kldekari|regency]] had advanced the positions of the high nobility whose influence he subsequently [[Battle of Sasireti|tried to limit]] when he assumed full ruling powers. Simultaneously, the Georgian crown was confronted with two formidable external foes: the Byzantine Empire and the resurgent [[Seljuq dynasty|Seljuq Turks]]. |

||

== Great Turkish Invasion == |

== Great Turkish Invasion == |

||

{{Main|Great Turkish Invasion}}The second half of the 11th century was marked by the strategically significant invasion of the [[Seljuq dynasty|Seljuq Turks]], who by the end of the 1040s had succeeded in building a vast empire including most of [[Central Asia]] and [[Iran|Persia]]. The Seljuk threat prompted the Georgian and Byzantine governments to seek a closer cooperation. To secure the alliance, Bagrat’s daughter [[Maria of Alania|Maria]] married, at some point between 1066 and 1071, to the Byzantine co-emperor [[Michael VII Doukas|Michael VII Ducas]]. |

{{Main|Great Turkish Invasion}}The second half of the 11th century was marked by the strategically significant invasion of the [[Seljuq dynasty|Seljuq Turks]], who by the end of the 1040s had succeeded in building a vast empire including most of [[Central Asia]] and [[Iran|Persia]]. The Seljuk threat prompted the Georgian and Byzantine governments to seek a closer cooperation. To secure the alliance, Bagrat’s daughter [[Maria of Alania|Maria]] married, at some point between 1066 and 1071, to the Byzantine co-emperor [[Michael VII Doukas|Michael VII Ducas]]. |

||

The Seljuqs made their first appearances in Georgia in the 1060s, when the sultan [[Alp Arslan]] laid waste to the south-western provinces of the Georgian kingdom and reduced [[Kingdom of Kakheti-Hereti|Kakheti]]. These intruders were part of the same wave of the Turkish movement which inflicted a crushing defeat on the Byzantine army at [[Battle of Manzikert|Manzikert]] in 1071. Although the Georgians were able to recover from Alp Arslan's invasion by securing the [[Tao (historical region)|Tao]] ([[Iberia (theme)|theme of Iberia]]), by the help of Byzantine governor, [[Gregory Pakourianos]], who began to evacuate the region shortly after the disaster inflicted by the Seljuks on the Byzantine army at Manzikert. On this occasion, [[George II of Georgia|George II]] was bestowed with the Byzantine title of ''[[Caesar (title)|Caesar]]'', granted the fortress of [[Kars]] and put in charge of the Imperial Eastern limits. This did not help to stem the Seljuk advance, however. The Byzantine withdrawal from Anatolia brought Georgia in more direct contact with the Seljuqs. Following the 1073 devastation of [[Kartli]] by the Seljuk sultan Alp Arslan, George II [[Battle of Partskhisi|successfully repelled an invasion]]. In 1076, the Seljuk sultan [[Malik Shah I]] surged into Georgia and reduced many settlements to ruins. Harassed by the massive Turkic influx, known in Georgian history as the [[Great Turkish Invasion]], from 1079/80 onward, George was pressured into submitting to Malik-Shah to ensure a precious degree of peace at the price of an annual [[tribute]]. |

|||

George's acceptance of the Seljuq suzerainty did not bring a real peace for Georgia. The Turks continued their seasonal movement into the Georgian territory to make use of the rich herbage of the [[Kura (Caspian Sea)|Kura valley]] and the Seljuq garrisons occupied the key fortresses in Georgia's south. These inroads and settlements had a ruinous effect on Georgia's economic and political order. Cultivated lands were turned into pastures for the nomads and peasant farmers were compelled to seek safety in the mountains. The contemporary Georgian chronicler laments that: {{cquote|''In those times there was neither sowing nor harvest. The land was ruined and turned into forest; in place of men beasts and animals of the field made their dwelling there. Insufferable oppression fell on all the inhabitants of the land; it was unparalleled and far worse than all ravages heard of or experienced.'' |

George's acceptance of the Seljuq suzerainty did not bring a real peace for Georgia. The Turks continued their seasonal movement into the Georgian territory to make use of the rich herbage of the [[Kura (Caspian Sea)|Kura valley]] and the Seljuq garrisons occupied the key fortresses in Georgia's south. These inroads and settlements had a ruinous effect on Georgia's economic and political order. Cultivated lands were turned into pastures for the nomads and peasant farmers were compelled to seek safety in the mountains. The contemporary Georgian chronicler laments that: {{cquote|''In those times there was neither sowing nor harvest. The land was ruined and turned into forest; in place of men beasts and animals of the field made their dwelling there. Insufferable oppression fell on all the inhabitants of the land; it was unparalleled and far worse than all ravages heard of or experienced.'' |

||

| Line 128: | Line 130: | ||

== Georgian Reconquista == |

== Georgian Reconquista == |

||

=== David IV === |

=== David IV === |

||

| ⚫ | [[File:King David Aghmashenebeli.jpg|thumb|[[David IV of Georgia]], a fresco from the [[Shio-Mgvime monastery]]|left|246x246px]][[File:David IV map de.png|thumb|Expansion of Kingdom of Georgia under [[David IV of Georgia|David IV]]'s reign.]]Watching his kingdom slip into chaos, [[George II of Georgia|George II]] ceded the crown to his 16-year-old son [[David IV of Georgia|David IV]] in 1089, who assumed the throne at the age of 16 in a period of [[Great Turkish Invasion]]s. As he came of age under the guidance of his court minister, [[George of Chqondidi]], David IV suppressed dissent of feudal lords and centralized the power in his hands to effectively deal with foreign threats. King David IV proved to be a capable statesman and military commander. In 1089–1100, he organized small detachments to harass and destroy isolated Seljuk troops and began the resettlement of desolate regions. In 1103 a major ecclesiastical congress known as the [[Council of Ruisi-Urbnisi|Ruis-Urbnisi Synod]] was held. By 1099 David IV's power was considerable enough that he was able to refuse paying [[tribute]] to Seljuqs. |

||

[[File:King David Aghmashenebeli.jpg|thumb|[[David IV of Georgia]], a fresco from the [[Shio-Mgvime monastery]]|left|246x246px]] |

|||

[[File:Didgori battle campaign map 1121.png|thumb|After pillaging the [[County of Edessa]], Seljuqid commander [[Ilghazi]] made peace with the [[Crusades|Crusaders]]. In 1121 he went north towards [[Armenia]] and with supposedly up to 250 000 - 350 000 troops, including men led by his son-in-law Sadaqah and Sultan Malik of [[Ganja, Azerbaijan|Ganja]], he invaded Georgia.]] |

|||

| ⚫ | Watching his kingdom slip into chaos, [[George II of Georgia|George II]] ceded the crown to his 16-year-old son [[David IV of Georgia|David IV]] in 1089, who assumed the throne at the age of 16 in a period of [[Great Turkish Invasion]]s. As he came of age under the guidance of his court minister, [[George of Chqondidi]], David IV suppressed dissent of feudal lords and centralized the power in his hands to effectively deal with foreign threats. King David IV proved to be a capable statesman and military commander. In 1089–1100, he organized small detachments to harass and destroy isolated Seljuk troops and began the resettlement of desolate regions. In 1103 a major ecclesiastical congress known as the [[Council of Ruisi-Urbnisi|Ruis-Urbnisi Synod]] was held. By 1099 David IV's power was considerable enough that he was able to refuse paying [[tribute]] to Seljuqs. |

||

[[File:David IV map de.png|thumb|Expansion of Kingdom of Georgia under [[David IV of Georgia|David IV]]'s reign.]] |

|||

To strengthen his army, King David launched a major [[Monaspa|military reform]] in 1118–1120 and [[Kipchaks in Georgia|resettled]] several thousand Kipchaks from the northern steppes to frontier districts of Georgia. In return, the Kipchaks provided one soldier per family, allowing King David to establish a standing army in addition to his royal troops. The new army provided the king with a much-needed force to fight both external threats and internal discontent of powerful lords. The Georgian-Kipchak alliance was facilitated by [[Family of David IV of Georgia|David's earlier marriage]] to the [[Khan (title)|Khan]]'s daughter. |

To strengthen his army, King David launched a major [[Monaspa|military reform]] in 1118–1120 and [[Kipchaks in Georgia|resettled]] several thousand Kipchaks from the northern steppes to frontier districts of Georgia. In return, the Kipchaks provided one soldier per family, allowing King David to establish a standing army in addition to his royal troops. The new army provided the king with a much-needed force to fight both external threats and internal discontent of powerful lords. The Georgian-Kipchak alliance was facilitated by [[Family of David IV of Georgia|David's earlier marriage]] to the [[Khan (title)|Khan]]'s daughter. |

||

| Line 150: | Line 151: | ||

=== Queen Tamar's reign === |

=== Queen Tamar's reign === |

||

[[File:Queentamar giorgi.jpg|thumb|left|180px|Queen Tamar and her father King [[George III of Georgia|George III]] (restored fresco from the [[Betania monastery]])]] |

[[File:Queentamar giorgi.jpg|thumb|left|180px|Queen Tamar and her father King [[George III of Georgia|George III]] (restored fresco from the [[Betania monastery]])]] |

||

The successes of his predecessors were built upon by [[Tamar of Georgia|Queen Tamar]], daughter of George III, who became the first female ruler of Georgia in her own right and under whose leadership the Georgian state reached the zenith of power and prestige in the Middle Ages. She not only shielded much of her Empire from further Turkish invasions but successfully pacified internal tensions, including a coup organized by her [[Kievan Rus|Russian]] husband [[Yury Bogolyubsky]], prince of [[Novgorod]].[[File:Medieval Georgian monasteries abroad-en.svg|thumb|227x227px|Medieval Georgian monasteries in [[Balkans]] and [[Near East]].]]In 1199, Tamar's armies led by two Christianised [[Kurds|Kurdish]]<ref>{{harvnb|Kuehn|2011|p=28}}.</ref> generals, Zakare and Ivane [[Zakarids-Mkhargrzeli|Mkhargrzeli]], dislodged the [[Shaddadid]] dynasty from [[Ani]]. At the beginning of the 13th century Georgian armies overran fortresses and cities towards the [[Ararat Plain]], reclaiming one after another fortresses and districts from local Muslim rulers: [[Bjni Fortress|Bjni]], [[Amberd]] and all the towns on their way in 1201 and [[Dvin (ancient city)|Dvin]] in 1203. Alarmed by the Georgian successes, [[Süleymanshah II]], the resurgent Seljuqid [[Sultanate of Rum|sultan of Rûm]], rallied his vassal [[Emir|emirs]] and marched against Georgia, but his camp was attacked and destroyed by Tamar's husband [[David Soslan]] at the [[Battle of Basian]] in 1203 or 1204. Exploiting her success in this battle, between 1203-1205 Georgians seized the town of [[Dvin (ancient city)|Dvin]]<ref>{{harvnb|Lordkipanidze|Hewitt|1987|p=150}}.</ref> and entered [[ |

The successes of his predecessors were built upon by [[Tamar of Georgia|Queen Tamar]], daughter of George III, who became the first female ruler of Georgia in her own right and under whose leadership the Georgian state reached the zenith of power and prestige in the Middle Ages. She not only shielded much of her Empire from further Turkish invasions but successfully pacified internal tensions, including a coup organized by her [[Kievan Rus|Russian]] husband [[Yury Bogolyubsky]], prince of [[Novgorod]].[[File:Medieval Georgian monasteries abroad-en.svg|thumb|227x227px|Medieval Georgian monasteries in [[Balkans]] and [[Near East]].]]In 1199, Tamar's armies led by two Christianised [[Kurds|Kurdish]]<ref>{{harvnb|Kuehn|2011|p=28}}.</ref> generals, Zakare and Ivane [[Zakarids-Mkhargrzeli|Mkhargrzeli]], dislodged the [[Shaddadids|Shaddadid]] dynasty from [[Ani]]. At the beginning of the 13th century Georgian armies overran fortresses and cities towards the [[Ararat Plain]], reclaiming one after another fortresses and districts from local Muslim rulers: [[Bjni Fortress|Bjni]], [[Amberd]] and all the towns on their way in 1201 and [[Dvin (ancient city)|Dvin]] in 1203. Alarmed by the Georgian successes, [[Suleiman II (Rûm)|Süleymanshah II]], the resurgent Seljuqid [[Sultanate of Rum|sultan of Rûm]], rallied his vassal [[Emir|emirs]] and marched against Georgia, but his camp was attacked and destroyed by Tamar's husband [[David Soslan]] at the [[Battle of Basian]] in 1203 or 1204. Exploiting her success in this battle, between 1203-1205 Georgians seized the town of [[Dvin (ancient city)|Dvin]]<ref>{{harvnb|Lordkipanidze|Hewitt|1987|p=150}}.</ref> and entered [[Shah-Armens|Akhlatshah]] possessions twice and subdued the [[Emir|emirs]] of [[Kars]], [[Shah-Armens|Akhlatshahs]], [[Saltukids|Erzurum]] and [[House of Mengüjek|Erzincan]].[[File:Georgian_invasion_of_northern_Iran.png|link=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Georgian_invasion_of_northern_Iran.png|thumb|221x221px|[[Georgian expedition to Iran]] in 1208 and 1210-1211 years.]]In 1206 the Georgian army, under the command of [[David Soslan]], captured [[Kars]] (vassal of the [[Saltukids]] in Erzurum) and other fortresses and strongholds along the [[Aras (river)|Araxes]]. This campaign was evidently started because the ruler of Erzerum refused to submit to Georgia. The emir of Kars requested aid from the [[Shah-Armens|Akhlatshahs]], but the latter was unable to respond, it was taken over by the [[Ayyubid dynasty|Ayyubids]] In 1207. By 1209 Georgia challenged Ayyubid rule in [[Eastern Anatolia Region|eastern Anatolia]]. Georgian army [[Georgian military campaign over Armenia#Confrontations with Ayyubids|besieged Akhlat]]. In response Ayyubid [[Sultan]] [[Al-Adil I|al-Adil]] assembled and personally led large muslim army that included the ''[[Emir|emirs]]'' of [[Homs]], [[Hama]] and [[Baalbek]] as well as contingents from other Ayyubid principalities to support [[Al-Awhad Ayyub|al-Awhad]]. During the siege, Georgian general [[Mkhargrdzeli|Ivane Mkhargrdzeli]] accidentally fell into the hands of the al-Awhad on the outskirts of Akhlat and demanded for his release a thirty-year truce. The Georgians had to lift the siege and conclude peace with the sultan. This brought the struggle for the Armenian lands to a stall,<ref name="Lordkipanidze-154">{{harvnb|Lordkipanidze|Hewitt|1987|p=154}}.</ref> leaving the [[Lake Van]] region to the [[Ayyubid dynasty|Ayyubids]] of [[Damascus]].<ref>{{harvnb|Humphreys|1977|pp=130–131}}.</ref>[[File:Iviron monastery.JPG|thumb|220x220px|During Tamara's reign, the Kingdom patronized Georgian-built religious centers overseas, such as this [[Iviron Monastery]]|left]]Among the remarkable events of Tamar's reign was the [[Georgian expedition to Chaldia|foundation]] of the [[Empire of Trebizond]] on the [[Black Sea]] in 1204. This state was established in the northeast of the crumbling [[Byzantine Empire]] with the help of the Georgian armies, which supported [[Alexios I of Trebizond]] and his brother, [[David Komnenos]], both of whom were Tamar's relatives.<ref>Tamar's paternal aunt was the [[Comnenoi]]'s grandmother on their father’s side, as it has been conjectured by [[Cyril Toumanoff]](1940).</ref> Alexios and David were fugitive Byzantine princes raised at the Georgian court. According to Tamar's historian, the aim of the [[Georgian expedition to Chaldia|Georgian expedition]] to [[Trabzon|Trebizond]] was to punish the Byzantine emperor [[Alexios IV Angelos|Alexius IV Angelus]] for his confiscation of a shipment of money from the Georgian queen to the monasteries of [[Antioch]] and [[Mount Athos]]. Tamar's Pontic endeavor can also be explained by her desire to take advantage of the [[Western Europe]]an [[Fourth Crusade]] against Constantinople to set up a friendly state in Georgia's immediate southwestern neighborhood, as well as by the dynastic solidarity to the dispossessed Comnenoi.<ref>Eastmond (1998), pp. 153–154.</ref><ref>Vasiliev (1935), pp. 15–19.</ref> |

||

As a retribution for the attack on Georgian-controlled city of [[Ani]], where 12,000 Christians were massacred in 1208, Georgia's Tamar the Great [[Georgian expedition to Iran|invaded and conquered]] the cities of [[Tabriz]], [[Ardabil]], [[Khoy]], [[Qazvin]]<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.ge/books?id=WjQfo3a1eVMC|title=Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1|last=Mikaberidze|first=Alexander|date=2011|publisher=ABC-CLIO|isbn=1598843362|location=Santa Barbara, California, USA|page=196}}</ref> and others along the way to [[Gorgan]]<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.ge/books?id=1kQOAQAAMAAJ|title=Encyclopaedia Iranica, Volume 2, Parts 5-8|last=Yar-Shater|first=Ehsan|date=2010|publisher=Routledge & Kegan Paul|isbn=|location=Abingdon, United Kingdom|page=892}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=|title=Histoire de la Géorgie depuis l'Antiquité jusqu'au XIXe siècle|last=Brosset|first=Marie-Felicite|date=1858|publisher=imprimerie de l'Académie Impériale des sciences|isbn=|location=France|page=468-472}}</ref> in northeast Persia.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.ge/books?id=RT0bAgAAQBAJ|title=Iran|last1=L. Baker|first1=Patricia|last2=Smith|first2=Hilary|last3=Oleynik|first3=Maria|date=2014|publisher=Bradt Travel Guides|isbn=1841624020|location=London, United Kingdom|page=158}}</ref> |

As a retribution for the attack on Georgian-controlled city of [[Ani]], where 12,000 Christians were massacred in 1208, Georgia's Tamar the Great [[Georgian expedition to Iran|invaded and conquered]] the cities of [[Tabriz]], [[Ardabil]], [[Khoy]], [[Qazvin]]<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.ge/books?id=WjQfo3a1eVMC|title=Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1|last=Mikaberidze|first=Alexander|date=2011|publisher=ABC-CLIO|isbn=1598843362|location=Santa Barbara, California, USA|page=196}}</ref> and others along the way to [[Gorgan]]<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.ge/books?id=1kQOAQAAMAAJ|title=Encyclopaedia Iranica, Volume 2, Parts 5-8|last=Yar-Shater|first=Ehsan|date=2010|publisher=Routledge & Kegan Paul|isbn=|location=Abingdon, United Kingdom|page=892}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=|title=Histoire de la Géorgie depuis l'Antiquité jusqu'au XIXe siècle|last=Brosset|first=Marie-Felicite|date=1858|publisher=imprimerie de l'Académie Impériale des sciences|isbn=|location=France|page=468-472}}</ref> in northeast Persia.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.ge/books?id=RT0bAgAAQBAJ|title=Iran|last1=L. Baker|first1=Patricia|last2=Smith|first2=Hilary|last3=Oleynik|first3=Maria|date=2014|publisher=Bradt Travel Guides|isbn=1841624020|location=London, United Kingdom|page=158}}</ref> |

||

| Line 173: | Line 174: | ||

=== Mongol yoke === |

=== Mongol yoke === |

||

[[File:Caucasus 1245 AD map de.png|thumb|Map of Kingdom of Georgia during [[Mongol invasions of Georgia|Mongol invasion]], 1245 AD.]] |

[[File:Caucasus 1245 AD map de.png|thumb|Map of Kingdom of Georgia during [[Mongol invasions of Georgia|Mongol invasion]], 1245 AD.]] |

||

Following the death of Queen Rusudan in 1245, an [[interregnum]] began during which the Mongols divided the Caucasus into eight [[Tumen (unit)|tumens]]. The Mongols created the "[[Vilayet]] of [[Georgia (country)#Etymology|Gurjistan]]", which included Georgia and the whole [[Transcaucasia|South Caucasus]], where they ruled indirectly, through the Georgian monarch, the latter to be confirmed by the [[Khagan|Great Khan]] upon his/her ascension.[[File:Damiane1.jpg|thumb|222x222px|Despite the Mongol conquests, Georgia continued to produce cultural landmarks, such as the frescoes of [[Ubisi]] by Damiane.|left]]Exploiting the complicated issue of succession, the Mongols had the Georgian nobles divided into two rival parties, each of which advocated their own candidate to the crown. These were [[David VII of Georgia|David VII "Ulu"]], an illegitimate son of George IV, and his cousin [[David VI of Georgia|David VI "Narin"]], son of Rusudan. After a [[Tsotne Dadiani#Kokhtastavi conspiracy|failed plot]] against the Mongol rule in Georgia (1245), [[Güyük Khan]] made, in 1247, both pretenders co-kings, in eastern and western parts of the kingdom respectively, they also carved out the region of [[Samtskhe atabegate|Samtskhe]] and [[Zakarid Armenia|Armenia]] and placed it under the direct control of the [[Ilkhanate]]. The system of |

Following the death of Queen Rusudan in 1245, an [[interregnum]] began during which the Mongols divided the Caucasus into eight [[Tumen (unit)|tumens]]. The Mongols created the "[[Vilayet]] of [[Georgia (country)#Etymology|Gurjistan]]", which included Georgia and the whole [[Transcaucasia|South Caucasus]], where they ruled indirectly, through the Georgian monarch, the latter to be confirmed by the [[Khagan|Great Khan]] upon his/her ascension.[[File:Damiane1.jpg|thumb|222x222px|Despite the Mongol conquests, Georgia continued to produce cultural landmarks, such as the frescoes of [[Ubisi]] by Damiane.|left]]Exploiting the complicated issue of succession, the Mongols had the Georgian nobles divided into two rival parties, each of which advocated their own candidate to the crown. These were [[David VII of Georgia|David VII "Ulu"]], an illegitimate son of George IV, and his cousin [[David VI of Georgia|David VI "Narin"]], son of Rusudan. After a [[Tsotne Dadiani#Kokhtastavi conspiracy|failed plot]] against the Mongol rule in Georgia (1245), [[Güyük Khan]] made, in 1247, both pretenders co-kings, in eastern and western parts of the kingdom respectively, they also carved out the region of [[Samtskhe atabegate|Samtskhe]] and [[Zakarid Armenia|Armenia]] and placed it under the direct control of the [[Ilkhanate]]. The system of tumens was abolished, but the Mongols closely watched the Georgian administration in order to secure a steady flow of taxes and tributes from the subject peoples, who were also pressed into the Mongol armies. Georgians attended all major campaigns of the [[Ilkhanate]] and aristocrats' sons served in [[kheshig]].<ref>C.P.Atwood- Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire, p.197</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

The period between 1259 and 1330 was marked by the struggle of the Georgians against the Mongol [[Ilkhanate]] for full independence. The first anti-Mongol uprising started in 1259 under the leadership of [[David VI of Georgia|King David Narin]] who in fact waged his war for almost thirty years. The Anti-Mongol strife went on under the Kings [[Demetrius II of Georgia|Demetrius II]] ({{Circa}} 1270–1289) and [[David VIII of Georgia|David VIII]] ({{Circa}} 1293–1311). |

The period between 1259 and 1330 was marked by the struggle of the Georgians against the Mongol [[Ilkhanate]] for full independence. The first anti-Mongol uprising started in 1259 under the leadership of [[David VI of Georgia|King David Narin]] who in fact waged his war for almost thirty years. The Anti-Mongol strife went on under the Kings [[Demetrius II of Georgia|Demetrius II]] ({{Circa}} 1270–1289) and [[David VIII of Georgia|David VIII]] ({{Circa}} 1293–1311). |

||

=== George V the Brilliant === |

|||

[[File:Caucasus 1311 AD map de.png|thumb|[[Kingdom of Imereti|Western]] and Eastern Georgia around 1311 AD.]]Demetrius was executed by the Mongols in 1289, and the little prince George was carried to Samtskhe to be reared at the court of his maternal grandfather, [[Beka I Jaqeli]]. In 1299, the [[Ilkhanate|Ilkhanid]] [[Khan (title)|khan]] [[Ghazan]] installed him as a rival ruler to George’s elder brother, the rebellious King [[David VIII of Georgia|David VIII]]. However, George’s authority did not extend beyond the Mongol-protected capital [[Tbilisi]], so George was referred to during this period as "The Shadow King of Tbilisi". In 1302, he was replaced by his brother, [[Vakhtang III of Georgia|Vakhtang III]]. After the death of both his elder brothers – David and Vakhtang – George became a regent for David’s son, [[George VI of Georgia|George VI]], who died underage in 1313, allowing George V to be crowned king for a second time. Having initially pledged his loyalty to the Il-khan [[Öljaitü]], he began a program of reuniting the Georgian lands. In 1315, he led the Georgian [[auxiliaries]] to suppress an anti-Mongol revolt in [[Asia Minor]], an expedition that would prove to be the last in which the Georgians fought in the Mongol ranks. In 1320, he drove the marauding [[Alans]] out of the town [[Gori, Georgia|Gori]] and forced them back to the [[Caucasus Mountains]]. [[File:Tiflis - Angelino Dulcert - 1339.jpg|thumb|217x217px|Detail from the [[Nautical chart]] by [[Angelino Dulcert]], depicting Georgian Black Sea coast and [[Tbilisi|Tiflis]], 1339|left]]He pursued a shrewd and flexible policy aimed at throwing off the Mongol yoke and restoring the Georgian kingdom. He established close relations with the Mongol khans and succeeded in acquiring authority to personally collect taxes on their behalf. Using Mongol force to his advantage, In 1329, George laid siege to [[Kutaisi]], western Georgia, reducing the [[Kingdom of Imereti|local king]] [[Bagrat I of Imereti|Bagrat I the Little]] to a vassal prince. King George was on friendly terms with the influential Mongol prince [[Chupan]], who was executed by [[Abu Sa'id Bahadur Khan|Abu Sa'id Khan]] in 1327. Subsequently, Iqbalshah, son of [[Kutlushah|Qutlughshah]], was appointed to be Mongol governor of Georgia ([[Gurjistan]]). In 1334 he reasserted royal authority over the virtually independent principality of [[Samtskhe atabegate|Samtskhe]] and returned the [[Empire of Trebizond]] into Georgia's sphere of influence. |

|||

In 1334, [[Hasan Buzurg|Shaykh Hasan]] of the [[Jalairid Sultanate|Jalayir]] was appointed as governor of Georgia by Abu Sai'd.<ref>Ta'rfkh-i Shaikh Uwais (History of Shaikh Uwais), trans. and ed. J. B. van Loon, The Hague, 1954, 56-58.</ref> However, George soon took advantage of the civil war in the Il-Khanate, where several khans were overthrown between 1335 and 1344, and drove the last remaining Mongol troops out of Georgia. The following year he ordered great festivities on the Mount Tsivi to celebrate the anniversary of the victory over the Mongols, and massacred there all oppositionist nobles. |

|||

Having restored the kingdom’s unity, he focused now on cultural, social and economic projects. He changed the coins issued by [[Ghazan]] khan with the Georgian ones, called George’s [[tetri]]. Between 1325 and 1338, he worked out two major law codes, [[Regulations of the Georgian Royal Court|one regulating the relations]] at the royal court and the other devised for the peace of a remote and disorderly mountainous district. Under him, Georgia established close international commercial ties, mainly with the [[Byzantine Empire]], but also with the great [[Europe|European]] [[maritime republics]], [[Republic of Genoa|Genoa]] and [[Republic of Venice|Venice]]. |

|||

In the year 1327 there occurred in Mongol Persia the most dramatic event of the reign of the Il-Khan [[Abu Sa'id (Ilkhanid dynasty)|Abu Sa'id]], namely the disgrace and execution of [[Chupan]], protégé of the Georgian king [[George V of Georgia|George V the Brilliant]]. Chupan's son [[Shaikh Mahmoud|Mahmud]], who commanded the Mongol garrison in Georgia, was arrested by his own troops and executed. Subsequently, Iqbalshah, son of Qutlughshah, was appointed to be Mongol governor of Georgia ([[Gurjistan]]).<ref>D. M. Lang - Georgia in the Reign of Giorgi the Brilliant (1314-1346). Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 17,No. 1 (1955), p.84</ref> In 1330–31 [[George V of Georgia|George]] used this loss as a pretext to rebel against the already weakened [[Ilkhanate]]. He pursued a shrewd and flexible policy aimed at throwing off the Mongol yoke and restoring the Georgian kingdom. He established close relations with the Mongol khans and succeeded in acquiring authority to personally collect taxes on their behalf. Using Mongol force to his advantage, In 1329, George laid siege to [[Kutaisi]], western Georgia, reducing the [[Kingdom of Imereti|local king]] [[Bagrat I of Imereti|Bagrat I the Little]] to a vassal prince. In 1334 he reasserted royal authority over the virtually independent principality of [[Samtskhe atabegate|Samtskhe]] and returned the [[Empire of Trebizond]] into Georgia's sphere of influence. [[File:Tiflis - Angelino Dulcert - 1339.jpg|thumb|217x217px|Detail from the [[Nautical chart]] by [[Angelino Dulcert]], depicting Georgian Black Sea coast and [[Tbilisi|Tiflis]], 1339]]In 1334, [[Hasan Buzurg|Shaykh Hasan]] of the [[Jalairid Sultanate|Jalayir]] was appointed as governor of Georgia by Abu Sai'd.<ref>Ta'rfkh-i Shaikh Uwais (History of Shaikh Uwais), trans. and ed. J. B. van Loon, The Hague, 1954, 56-58.</ref> However, George soon took advantage of the civil war in the Il-Khanate, where several khans were overthrown between 1335 and 1344, and drove the last remaining Mongol troops out of Georgia.Having restored the kingdom’s unity, he focused now on cultural, social and economic projects. He changed the coins issued by [[Ghazan]] khan with the Georgian ones, called George’s [[tetri]]. Between 1325 and 1338, he worked out two major law codes, [[Regulations of the Royal Court|one regulating the relations]] at the royal court and the other devised for the peace of a remote and disorderly mountainous district. Under him, Georgia established close international commercial ties, mainly with the [[Byzantine Empire]], but also with the great [[Europe|European]] [[maritime republics]], [[Republic of Genoa|Genoa]] and [[Republic of Venice|Venice]]. |

|||

===Timur's invasions=== |

===Timur's invasions=== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Main|Timur's invasions of Georgia}} |

{{Main|Timur's invasions of Georgia}} |

||

| Line 198: | Line 206: | ||

== Final disintegration == |

== Final disintegration == |

||

[[File:Caucasus 1450 map de.png|thumb|250x250px|Map of Caucasus Region 1460.]] |

[[File:Caucasus 1450 map de.png|thumb|250x250px|Map of Caucasus Region 1460.]] |

||

The political split of the kingdom was speeded up by the [[Eristavi|Eristavs]] of [[Samtskhe atabegate|Samtskhe]]. In 1462 [[Qvarqvare II Jaqeli|Kvarkvare II Jakeli]] called against the king of Georgia the leader of the [[Aq Qoyunlu]], [[Uzun Hasan]], who invaded [[Kartli]]. His invasion was used by the king's governor of the west Georgia |

The political split of the kingdom was speeded up by the [[Eristavi|Eristavs]] of [[Samtskhe atabegate|Samtskhe]]. In 1462 [[Qvarqvare II Jaqeli|Kvarkvare II Jakeli]] called against the king of Georgia the leader of the [[Aq Qoyunlu]], [[Uzun Hasan]], who invaded [[Kartli]]. His invasion was used by the king's governor of the west Georgia – [[Bagrat VI of Georgia|Bagrat VI]]. In 1463 Bagrat VI defeated [[George VIII of Georgia|Giorgi VIII]] at Chikhori. "[[House of Dadiani|Dadiani]], [[House of Gurieli|Gurieli]], [[Principality of Abkhazia|Abkhazians]] and [[Principality of Svaneti|Svans]] came to the conqueror and expressing the wish of all the Imerians (westerners) blessed him to be King. From that time [[Kingdom of Imereti|Imereti]] turned into one kingdom and four Duchies or [[satavado]], as [[House of Dadiani|Dadiani]] was allotted [[Odishi]], [[House of Gurieli|Gurieli]] - [[Principality of Guria|Guria]], [[House of Shervashidze|Sharvashidze]] - [[Principality of Abkhazia|Abkhazia]] and [[Sochi|Jiketi]], [[House of Gelovani|Gelovani]] - [[Principality of Svaneti|Svaneti]]; and Bagrat was their King". |

||

Bagrat was the king of only west Georgia for a short period. In 1466 he crossed the borders of East Georgia (Inner [[Shida Kartli|Kartli]]) and proclaimed himself [[List of monarchs of Georgia#Kings of unified Georgia (1008–1490)|King of all Georgia]]. In fact, he possessed only west Georgia and Inner Kartli. Giorgi VIII was consolidated in [[Kakheti]] and formed an independent [[Kingdom of Kakheti|Kakhetian Kingdom]]. In the [[Kvemo Kartli|lower Kartli]] ([[Tbilisi]]) was consolidated the grandson of [[Alexander I of Georgia|Alexander I the Great]] |

Bagrat was the king of only west Georgia for a short period. In 1466 he crossed the borders of East Georgia (Inner [[Shida Kartli|Kartli]]) and proclaimed himself [[List of monarchs of Georgia#Kings of unified Georgia (1008–1490)|King of all Georgia]]. In fact, he possessed only west Georgia and Inner Kartli. Giorgi VIII was consolidated in [[Kakheti]] and formed an independent [[Kingdom of Kakheti|Kakhetian Kingdom]]. In the [[Kvemo Kartli|lower Kartli]] ([[Tbilisi]]) was consolidated the grandson of [[Alexander I of Georgia|Alexander I the Great]] – [[Constantine II of Georgia|Constantine II]], son of [[Demetrius, Duke of Imereti|Demetrius]], recognizing as a sovereign of Bagrat VI. [[Samtskhe atabegate|Samtskhe-Saatabago]] became an independent principality. |

||

[[File:Caucasus 1490 map de.png|thumb|250x250px|Map of Caucasus Region 1490.]] |

[[File:Caucasus 1490 map de.png|thumb|250x250px|Map of Caucasus Region 1490.]] |

||

In 1477 [[Vameq II Dadiani|Vamek II Dadiani]] opposed Bagrat VI. He "assembled the Abkhazians and Gurians and began the raids, devastation and capturing of Imereti". The reaction of the king of Georgia was immediate. Bagrat VI attacked Odishi with the great army, defeated and subdued Vamek II Dadiani. The king of Kartli and west Georgia |

In 1477 [[Vameq II Dadiani|Vamek II Dadiani]] opposed Bagrat VI. He "assembled the Abkhazians and Gurians and began the raids, devastation and capturing of Imereti". The reaction of the king of Georgia was immediate. Bagrat VI attacked Odishi with the great army, defeated and subdued Vamek II Dadiani. The king of Kartli and west Georgia – Bagrat VI died in 1478. Constantine II ascended the throne of [[Kingdom of Kartli|Kartli]]. The son of Bagrat VI – [[Alexander II of Imereti|Alexander]] tried to ascend the throne in west Georgia. For coronation he summoned "Dadiani, Gurieli, Sharvashidze and Gelovani", but headed with Vamek II Dadiani refused to support him and invited Constantine II to West Georgia. Constantine with the help of the Eristavs of western Georgia took Kutaisi and for a short time restored the integrity of Kartli with western Georgia. The allies were planning to unite the whole Georgia and in the first place tried to join Samtskhe-Saatabago. Vamek II Dadiani with the army of west Georgia helped Constantine II in 1481 in the battle with [[Atabeg|atabag]] and after this the King subordinated Samtskhe. Constantine II became the King of All Georgia. He "subdued Imers, Odishians and Abkhazians; Atabag served him and the Kakhetians were in his subordination. |

||

in 1483 Constantine II was defeated at Aradeti in the battle with Atabag. The son of Bagrat |

in 1483 Constantine II was defeated at Aradeti in the battle with Atabag. The son of Bagrat – [[Alexander II of Imereti|Alexander]], later known as Alexander II took advantage of it and captured Kutaisi and was crowned as a King. Then, the new possessor of Odishi - [[Liparit II Dadiani]] invited Constantine II to West Georgia for the second time. In 1487 Constantine came to west Georgia again with the army and occupied Kutaisi and other significant fortresses with the help of Liparit II Dadiani and other great feudals of West Georgia. But he failed to fully annex west Georgia. In 1488 [[Yaqub bin Uzun Hasan|Yaqub b. Uzun Hasan]] invaded East Georgia and the king of Kartli went to fight with him. Alexander II took advantage of it and captured Kutaisi and all fortresses of Imereti again and after that "reconciled with Dadiani and Gurieli. By this act, he pacified Imereti and firmly subdued the Abkhazians and Svans". |

||

In 1490 Constantine asked a specially assembled [[Darbazi (State Council)|royal court]] for an advice concerning restoration of the integral kingdom. The royal court advised Constantine II to postpone this struggle till the better times. After this the king of [[Kingdom of Kartli|Kartli]] had to temporarily reconcile with the kings of [[Kingdom of Kakheti|Kakheti]] and [[Kingdom of Imereti|Imereti]] and also [[Atabeg|Atabag]] of [[Samtskhe atabegate|Samtskhe]] having thus formed the factual split of Georgia. Its unity was finally shattered and, by 1490/91, the once powerful monarchy fragmented into three independent kingdoms – [[Kingdom of Kartli (1484-1762)|Kartli]] (central to eastern Georgia), [[Kingdom of Kakheti|Kakheti]] (eastern Georgia), and [[Kingdom of Imereti|Imereti]] (western Georgia) – each led by the rival branches of the Bagrationi dynasty, and into five semi-independent principalities – [[Odishi]] (Mingrelia), [[Guria]], [[Principality of Abkhazia|Abkhazia]], [[Svaneti]] |

In 1490 Constantine asked a specially assembled [[Darbazi (State Council)|royal court]] for an advice concerning restoration of the integral kingdom. The royal court advised Constantine II to postpone this struggle till the better times. After this the king of [[Kingdom of Kartli|Kartli]] had to temporarily reconcile with the kings of [[Kingdom of Kakheti|Kakheti]] and [[Kingdom of Imereti|Imereti]] and also [[Atabeg|Atabag]] of [[Samtskhe atabegate|Samtskhe]] having thus formed the factual split of Georgia. Its unity was finally shattered and, by 1490/91, the once powerful monarchy fragmented into three independent kingdoms – [[Kingdom of Kartli (1484-1762)|Kartli]] (central to eastern Georgia), [[Kingdom of Kakheti|Kakheti]] (eastern Georgia), and [[Kingdom of Imereti|Imereti]] (western Georgia) – each led by the rival branches of the Bagrationi dynasty, and into five semi-independent principalities – [[Odishi]] (Mingrelia), [[Guria]], [[Principality of Abkhazia|Abkhazia]], [[Svaneti]] and [[Samtskhe-Saatabago|Samtskhe]] – dominated by their own feudal clans. |

||

== Government and Society == |

== Government and Society == |

||

Revision as of 21:09, 13 June 2018

Kingdom of Georgia | |

|---|---|

| 1008–1463-1490 | |

Kingdom of Georgia in 1184-1230 at the peak of its might:

| |

| Capital | |

| Common languages | Official Georgian |

| Religion | Dominant Orthodox Christianity (Georgian Orthodox Church) Minor |

| Government | Feudal Monarchy |

| King, King of Kings | |

• 978–1014 | Bagrat III (first) |

• 1446–1465 | George VIII (last) |

| Historical era | High Middle Ages to Late Middle Ages |

| 1008 | |

| 1060-1121 | |

| 1184-1226 | |

| 1238-1335 | |

| 1386-1403 | |

• Civil War | 1463-1490 |

• Disintegration[A] | 1490-1493 |

| Area | |

| 1213-1245 | 380,000 km2 (150,000 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 13th century | 2,400,000−2,500,000[1] |

| Currency | Various Byzantine and Sassanian coins were minted until the 12th century. Dirham came into use after 1122.[2] |

| ISO 3166 code | GE |

| Today part of | Countries today

|

The Kingdom of Georgia (Georgian: საქართველოს სამეფო), also known as the Georgian Empire,[3][4][5][6] was a medieval monarchy which emerged circa 1008 AD. It reached its Golden Age of political and economic strength during the reign of King David IV and Queen Tamar the Great from 11th to 13th centuries. Georgia became one of the pre-eminent nations of the Christian East, her pan-Caucasian empire stretching, at its largest extent, from the North Caucasus to Northern Iran, and westwards into Asia Minor, while also maintaining religious possessions abroad, such as the Monastery of the Cross and Iviron. It was the principal historical precursor of present-day Georgia.

Lasting for several centuries, the kingdom fell to the Mongol invasions in the 13th century, but managed to re-assert sovereignty by the 1340s. The following decades were marked by Black Death, as well as numerous invasions under the leadership of Timur, who devastated the country's economy, population, and urban centers. The Kingdom's geopolitical situation further worsened after the fall of the Empire of Trebizond. As a result of these processes, by the end of the 15th century Georgia turned into a fractured entity. Renewed incursions by Timur from 1386, and the later invasions by the Kara Koyunlu and Ak Koyunlu led to the final collapse of the kingdom into anarchy by 1466 and the mutual recognition of its constituent kingdoms of Kartli, Kakheti and Imereti as independent states between 1490 and 1493 – each led by a rival branch of the Bagrationi dynasty, and into five semi-independent principalities – Odishi, Guria, Abkhazia, Svaneti, and Samtskhe – dominated by their own feudal clans.

Background

During the classical era, several independent kingdoms were established in what is now Georgia, such as Colchis, later known as Lazica and Iberia. The Georgians adopted Christianity in the early 4th century, giving a great stimulus to the development of literature, arts, and ultimately playing a key role in the further formation of the unified Georgian nation.

Located on the crossroads of protracted Roman–Persian wars, the early Georgian kingdoms disintegrated into various feudal regions by the early Middle Ages. This made it easy for the remaining Georgian realms to fall prey to the early Muslim conquests in the 7th century. After the wide political and cultural changes brought about by the Muslim conquests, refugees from the Iberia took shelter in the West, either in Abkhazia or Tao-Klarjeti, and brought there their culture.

In struggle against the Arab occupation, Bagrationi dynasty came to rule over Tao-Klarjeti, former southern provinces of Iberia, and established Kouropalatate of Iberia as a nominal vassal of the Byzantine Empire. The restoration of the Iberian kingship begins in 888, when Adarnase IV of Iberia took the title of "King of Iberia". However, the Bagrationi dynasty failed to maintain the integrity of their kingdom, which was actually divided between the two branches of the family with the main branch retaining in Tao and another controlling Klarjeti.

An Arab incursion into western Georgia was repelled by Abasgians jointly with Lazic and Iberian allies in 736, towards c.786, Leon II won his full independence from Byzantine and transferred his capital to the western Georgian city of Kutaisi, thus unifying Lazica and Abasgia via a dynastic union. The increasingly expansionist tendencies of the kingdom led to the enlargement of its realm to the east. In 9th century western Georgian Church broke away from Constantinople and recognized the authority of the Catholicate of Mtskheta; language of the church in Abkhazia shifted from Greek to Georgian, as Byzantine power decreased and doctrinal differences disappeared.[7] It is not accidental that the process of unification of Georgia in a single feudal kingdom began with the struggle of the Abkhazian principality against Byzantium, fighting for hegemony within the Georgian territories.

Unification of the Georgian State

At the end of the 10th century David III of Tao invaded the Kartli and gave it to his foster-son Bagrat III and installed his father Gurgen as his regent, who was later crowned as "King of Kings of the Iberians" in 994. Through his mother Gurandukht, sister of the childless Abkhazian king Theodosius III (c. 975-978), Bagrat was a potential heir to the realm of Abkhazia. Three years later, after the death of Theodosius III, Bagrat III inherited the Abkhazian throne. In 1008, Gurgen died, and Bagrat succeeded him as "King of the Iberians", thus becoming the first King of a unified realm of Abkhazia and Iberia. After he had secured his patrimony, Bagrat proceeded to press a claim to the easternmost Georgian kingdom of Kakheti-Hereti and annexed it in or around 1010, after two years of fighting and aggressive diplomacy.

Bagrat’s reign, a period of uttermost importance in the history of Georgia, brought about the final victory of the Georgian Bagratids in the centuries-long power struggles. Anxious to create more stable and centralized monarchy, Bagrat eliminated or at least diminished the autonomy of the dynastic princes. In his eyes, the most possible internal danger came from the Klarjeti line of the Bagrationi. To secure the succession to his son, George I, Bagrat lured his cousins, on pretext of a reconciliatory meeting and threw them in prison in 1010. Bagrat’s foreign policy was generally peaceful and the king successfully manoeuvred to avoid the conflicts with both the Byzantine and Muslim neighbours even though David's domains of Tao remained in the Byzantine and Tbilisi in the Arab hands.

War and peace with Byzantium

The major political and military event during George I’s reign, a war against the Byzantine Empire, had its roots back to the 990s, when the Georgian prince David III of Tao, following his abortive rebellion against Emperor Basil II, had to agree to cede his extensive possessions in Tao to the emperor on his death. All the efforts by David’s stepson and George’s father, Bagrat III, to prevent these territories from being annexed to the empire went in vain. Young and ambitious, George launched a campaign to restore the Curopalates’ succession to Georgia and occupied Tao in 1015–1016. Byzantines were at that time involved in a relentless war with the Bulgar Empire, limiting their actions to the west. But as soon as Bulgaria was conquered, Basil II led his army against Georgia (1021). An exhausting war lasted for two years, and ended in a decisive Byzantine victory, forcing George to agree to a peace treaty, in which he had not only to abandon his claims to Tao, but to surrender several of his southwestern possessions, later reorganized into theme of Iberia, to Basil and to give his three-year-old son, Bagrat IV, as hostage.

The young child Bagrat IV spent the next three years in the imperial capital of Constantinople and was released in 1025. After George I's death in 1027, Bagrat, aged eight, succeeded to the throne. By the time Bagrat IV became king, the Bagratids’ drive to complete the unification of all Georgian lands had gained irreversible momentum. The kings of Georgia sat at Kutaisi in western Georgia from which they ran all of what had been the Kingdom of Abkhazia and a greater portion of Iberia; Tao had been lost to the Byzantines while a Muslim emir remained in Tbilisi and the kings of Kakheti-Hereti obstinately defended their autonomy in easternmost Georgia. Furthermore, the loyalty of great nobles to the Georgian crown was far from stable. During Bagrat’s minority, the regency had advanced the positions of the high nobility whose influence he subsequently tried to limit when he assumed full ruling powers. Simultaneously, the Georgian crown was confronted with two formidable external foes: the Byzantine Empire and the resurgent Seljuq Turks.

Great Turkish Invasion

The second half of the 11th century was marked by the strategically significant invasion of the Seljuq Turks, who by the end of the 1040s had succeeded in building a vast empire including most of Central Asia and Persia. The Seljuk threat prompted the Georgian and Byzantine governments to seek a closer cooperation. To secure the alliance, Bagrat’s daughter Maria married, at some point between 1066 and 1071, to the Byzantine co-emperor Michael VII Ducas.

The Seljuqs made their first appearances in Georgia in the 1060s, when the sultan Alp Arslan laid waste to the south-western provinces of the Georgian kingdom and reduced Kakheti. These intruders were part of the same wave of the Turkish movement which inflicted a crushing defeat on the Byzantine army at Manzikert in 1071. Although the Georgians were able to recover from Alp Arslan's invasion by securing the Tao (theme of Iberia), by the help of Byzantine governor, Gregory Pakourianos, who began to evacuate the region shortly after the disaster inflicted by the Seljuks on the Byzantine army at Manzikert. On this occasion, George II was bestowed with the Byzantine title of Caesar, granted the fortress of Kars and put in charge of the Imperial Eastern limits. This did not help to stem the Seljuk advance, however. The Byzantine withdrawal from Anatolia brought Georgia in more direct contact with the Seljuqs. Following the 1073 devastation of Kartli by the Seljuk sultan Alp Arslan, George II successfully repelled an invasion. In 1076, the Seljuk sultan Malik Shah I surged into Georgia and reduced many settlements to ruins. Harassed by the massive Turkic influx, known in Georgian history as the Great Turkish Invasion, from 1079/80 onward, George was pressured into submitting to Malik-Shah to ensure a precious degree of peace at the price of an annual tribute.

George's acceptance of the Seljuq suzerainty did not bring a real peace for Georgia. The Turks continued their seasonal movement into the Georgian territory to make use of the rich herbage of the Kura valley and the Seljuq garrisons occupied the key fortresses in Georgia's south. These inroads and settlements had a ruinous effect on Georgia's economic and political order. Cultivated lands were turned into pastures for the nomads and peasant farmers were compelled to seek safety in the mountains. The contemporary Georgian chronicler laments that:

In those times there was neither sowing nor harvest. The land was ruined and turned into forest; in place of men beasts and animals of the field made their dwelling there. Insufferable oppression fell on all the inhabitants of the land; it was unparalleled and far worse than all ravages heard of or experienced.

Georgian Reconquista

David IV

Watching his kingdom slip into chaos, George II ceded the crown to his 16-year-old son David IV in 1089, who assumed the throne at the age of 16 in a period of Great Turkish Invasions. As he came of age under the guidance of his court minister, George of Chqondidi, David IV suppressed dissent of feudal lords and centralized the power in his hands to effectively deal with foreign threats. King David IV proved to be a capable statesman and military commander. In 1089–1100, he organized small detachments to harass and destroy isolated Seljuk troops and began the resettlement of desolate regions. In 1103 a major ecclesiastical congress known as the Ruis-Urbnisi Synod was held. By 1099 David IV's power was considerable enough that he was able to refuse paying tribute to Seljuqs.

To strengthen his army, King David launched a major military reform in 1118–1120 and resettled several thousand Kipchaks from the northern steppes to frontier districts of Georgia. In return, the Kipchaks provided one soldier per family, allowing King David to establish a standing army in addition to his royal troops. The new army provided the king with a much-needed force to fight both external threats and internal discontent of powerful lords. The Georgian-Kipchak alliance was facilitated by David's earlier marriage to the Khan's daughter.

Starting in 1120, King David began a more aggressive policy of expansion. Muslim powers became increasingly concerned about the rapid rise of a Christian state in southern Caucasia. In 1121, Sultan Mahmud b. Muhammad (c. 1118–1131) declared a holy war on Georgia. However, 12 August 1121, King David routed the enemy army on the fields of Didgori, with fleeing Seljuq Turks being run down by pursuing Georgian cavalry for several days. A huge amount of booty and prisoners were captured by David's army, which had also secured Tbilisi and inaugurated Georgia's Golden Age.[8]

A well-educated man, he preached tolerance and acceptance of other religions, abrogated taxes and services for the Muslims and Jews, and protected the Sufis and Muslim scholars. In 1123, David’s army liberated Dmanisi, the last Seljuk stronghold in southern Georgia. In 1124, David finally conquered Shirvan and took the Armenian city of Ani from the Muslim emirs, thus expanding the borders of his kingdom to the Araxes basin. Armenians met him as a liberator providing some auxiliary force for his army. It was when the important component of "Sword of the Messiah" appeared in the title of David the Builder.

David IV founded the Gelati Academy, which became an important center of scholarship in the Eastern Orthodox Christian world of that time. Due to the extensive work carried out by the Gelati Academy, people of the time called it "a new Hellas" and "a second Athos".[9] David also played a personal role in reviving Georgian religious hymnography, composing the Hymns of Repentance, a sequence of eight free-verse psalms. In this emotional repentance of his sins, David sees himself as reincarnating the Biblical David, with a similar relationship to God and to his people. His hymns also share the idealistic zeal of the contemporaneous European crusaders to whom David was a natural ally in his struggle against the Seljuks.[10][verification needed]

The reign of Demetrius I and George III

The kingdom continued to flourish under Demetrius I, the son of David. Although his reign saw a disruptive family conflict related to royal succession, Georgia remained a centralized power with a strong military. In 1139, he raided the city of Ganja in Arran. He brought the iron gate of the defeated city to Georgia and donated it to Gelati Monastery at Kutaisi, western Georgia. Despite this brilliant victory, Demetrius could hold Ganja only for a few years.[11][12] A talented poet, Demetrius also continued his father's contributions to Georgia's religious polyphony. The most famous of his hymns is Thou Art a Vineyard, which is dedicated to Virgin Mary, the patron saint of Georgia, and is still sung in Georgia's churches 900 years after its creation.

Demetrius was succeeded by his son George III in 1156, beginning a stage of more offensive foreign policy. The same year he ascended to the throne, George launched a successful campaign against the Seljuq sultanate of Ahlat. He freed the important Armenian town of Dvin from Turkish vassalage and was thus welcomed as a liberator in the area. In 1167, he marched to defend his vassal Shah Aghsartan of Shirvan against the Khazar and Kipchak assaults and strengthened the Georgian dominance in the area. George gave his daughter Rusudan, in marriage, to Manuel Komnenos, the son of Emperor Andronikos I Komnenos. In 1177, the nobles rose in rebellion but were suppressed. The following year, King Giorgi III ceded the throne to his daughter Tamar, but remained coregent until his death in 1184.

Golden age

The unified monarchy maintained its precarious independence from the Byzantine and Seljuk empires throughout the 11th century, and flourished under David IV the Builder (c. 1089–1125), who repelled the Seljuk attacks and essentially completed the unification of Georgia with the re-conquest of Tbilisi in 1122.[13] In spite of repeated incidents of dynastic strife, the kingdom continued to prosper during the reigns of Demetrios I (c.1125–1156), George III (c.1156–1184), and especially, his daughter Tamar (c.1184–1213).

With the decline of Byzantine power and the dissolution of the Great Seljuk Empire, Georgia became one of the pre-eminent nations of the region, stretching, at its largest extent, from present-day Southern Russia to Northern Iran, and westwards into Anatolia. The Kingdom of Georgia brought about the Georgian Golden Age, which describes a historical period in the High Middle Ages, spanning from roughly the late 11th to 13th centuries, when the kingdom reached the zenith of its power and development. The period saw the flourishing of medieval Georgian architecture, painting and poetry, which was frequently expressed in the development of ecclesiastic art, as well as the creation of first major works of secular literature. It was a period of military, political, economical and cultural progress. It also included the so-called Georgian Renaissance (also called Eastern Renaissance[14]), during which various human activities, forms of craftsmanship and art, such as literature, philosophy and architecture thrived in the kingdom.[15]

Queen Tamar's reign

The successes of his predecessors were built upon by Queen Tamar, daughter of George III, who became the first female ruler of Georgia in her own right and under whose leadership the Georgian state reached the zenith of power and prestige in the Middle Ages. She not only shielded much of her Empire from further Turkish invasions but successfully pacified internal tensions, including a coup organized by her Russian husband Yury Bogolyubsky, prince of Novgorod.

In 1199, Tamar's armies led by two Christianised Kurdish[16] generals, Zakare and Ivane Mkhargrzeli, dislodged the Shaddadid dynasty from Ani. At the beginning of the 13th century Georgian armies overran fortresses and cities towards the Ararat Plain, reclaiming one after another fortresses and districts from local Muslim rulers: Bjni, Amberd and all the towns on their way in 1201 and Dvin in 1203. Alarmed by the Georgian successes, Süleymanshah II, the resurgent Seljuqid sultan of Rûm, rallied his vassal emirs and marched against Georgia, but his camp was attacked and destroyed by Tamar's husband David Soslan at the Battle of Basian in 1203 or 1204. Exploiting her success in this battle, between 1203-1205 Georgians seized the town of Dvin[17] and entered Akhlatshah possessions twice and subdued the emirs of Kars, Akhlatshahs, Erzurum and Erzincan.

In 1206 the Georgian army, under the command of David Soslan, captured Kars (vassal of the Saltukids in Erzurum) and other fortresses and strongholds along the Araxes. This campaign was evidently started because the ruler of Erzerum refused to submit to Georgia. The emir of Kars requested aid from the Akhlatshahs, but the latter was unable to respond, it was taken over by the Ayyubids In 1207. By 1209 Georgia challenged Ayyubid rule in eastern Anatolia. Georgian army besieged Akhlat. In response Ayyubid Sultan al-Adil assembled and personally led large muslim army that included the emirs of Homs, Hama and Baalbek as well as contingents from other Ayyubid principalities to support al-Awhad. During the siege, Georgian general Ivane Mkhargrdzeli accidentally fell into the hands of the al-Awhad on the outskirts of Akhlat and demanded for his release a thirty-year truce. The Georgians had to lift the siege and conclude peace with the sultan. This brought the struggle for the Armenian lands to a stall,[18] leaving the Lake Van region to the Ayyubids of Damascus.[19]

Among the remarkable events of Tamar's reign was the foundation of the Empire of Trebizond on the Black Sea in 1204. This state was established in the northeast of the crumbling Byzantine Empire with the help of the Georgian armies, which supported Alexios I of Trebizond and his brother, David Komnenos, both of whom were Tamar's relatives.[20] Alexios and David were fugitive Byzantine princes raised at the Georgian court. According to Tamar's historian, the aim of the Georgian expedition to Trebizond was to punish the Byzantine emperor Alexius IV Angelus for his confiscation of a shipment of money from the Georgian queen to the monasteries of Antioch and Mount Athos. Tamar's Pontic endeavor can also be explained by her desire to take advantage of the Western European Fourth Crusade against Constantinople to set up a friendly state in Georgia's immediate southwestern neighborhood, as well as by the dynastic solidarity to the dispossessed Comnenoi.[21][22]

As a retribution for the attack on Georgian-controlled city of Ani, where 12,000 Christians were massacred in 1208, Georgia's Tamar the Great invaded and conquered the cities of Tabriz, Ardabil, Khoy, Qazvin[23] and others along the way to Gorgan[24][25] in northeast Persia.[26]

The country's power had grown to such extent that in the later years of Tamar's rule, the Kingdom was primarily concerned with the protection of the Georgian monastic centers in the Holy Land, eight of which were listed in Jerusalem.[27] Saladin's biographer Bahā' ad-Dīn ibn Šaddād reports that, after the Ayyubid conquest of Jerusalem in 1187, Tamar sent envoys to the sultan to request that the confiscated possessions of the Georgian monasteries in Jerusalem be returned. Saladin's response is not recorded, but the queen's efforts seem to have been successful.[28] Ibn Šaddād furthermore claims that Tamar outbid the Byzantine emperor in her efforts to obtain the relics of the True Cross, offering 200,000 gold pieces to Saladin who had taken the relics as booty at the battle of Hattin – to no avail, however.[29]

Nomadic invasions

The reign of George IV and Rusudan

George IV continued Tamar's policy of strengthening of the Georgian feudal state. Georgia's largely isolationist policies had allowed it to accumulate a powerful army and a very large concentration of knights. He put down the revolts in neighbouring Muslim vassal states in the 1210s and began preparations for a large-scale campaign against Jerusalem to support the Crusaders in 1220. However, the Mongol approach to the Georgian borders made the Crusade plan unrealistic, the reconnaissance force under the Mongols Jebe and Subutai destroyed the entire Georgian army in two successive battles, in 1221–1222, most notably the Battle of Caucasus Mountain.

Georgians suffered heavy losses in this war and the King George IV, himself was severely wounded. The Kingdom of Georgia itself was torn by internal dissent and was unprepared for such an ordeal. The struggle between the nobility and the crown increased. In 1222, King George appointed his sister Rusudan as a co-regent and died later that year. Queen Rusudan (c. 1223–1245) proved a less capable ruler, and domestic discord intensified on the eve of foreign invasion.

This offensive, which would prove the ruin of Georgia, was preceded by the devastating conflict with Khwarazm ruler Jalal ad-Din Mingburnu, the son of the last ruler of Khwarazm, who was defeated by the Mongols and now led his Khwaras mian army to Caucasus. The Georgians suffered bitter defeat at the Battle of Garni, and the royal court with Queen Rusudan moved to Kutaisi, when the Georgian capital Tbilisi was besieged by the Khwarezmians. The victorious Khwarezmid soldiers sacked Tbilisi and massacred its Christian population and terminated Georgia’s "Golden Age". Jalal al-Din continued devastating Georgian regions until 1230, when the Mongols finally defeated him.

In 1235–1236, Mongol forces, unlike their first raid in 1221, appeared with the sole purpose of conquest and occupation and easily overran the already devastated Kingdom. Queen Rusudan fled to the security of western Georgia, while the nobles secluded themselves in their fortresses. By 1240 all the country was under the Mongol yoke. Forced to accept the sovereignty of the Mongol Khan in 1242, Rusudan had to pay an annual tribute of 50,000 gold pieces and support the Mongols with a Georgian army.

Fearing that her nephew David VII of Georgia would aspire to the throne, Rusudan held him prisoner at the court of her son-in-law, the sultan Kaykhusraw II, and sent her son David VI of Georgia to the Mongol court to get his official recognition as heir apparent. She died in 1245, still waiting for her son to return.

Mongol yoke

Following the death of Queen Rusudan in 1245, an interregnum began during which the Mongols divided the Caucasus into eight tumens. The Mongols created the "Vilayet of Gurjistan", which included Georgia and the whole South Caucasus, where they ruled indirectly, through the Georgian monarch, the latter to be confirmed by the Great Khan upon his/her ascension.

Exploiting the complicated issue of succession, the Mongols had the Georgian nobles divided into two rival parties, each of which advocated their own candidate to the crown. These were David VII "Ulu", an illegitimate son of George IV, and his cousin David VI "Narin", son of Rusudan. After a failed plot against the Mongol rule in Georgia (1245), Güyük Khan made, in 1247, both pretenders co-kings, in eastern and western parts of the kingdom respectively, they also carved out the region of Samtskhe and Armenia and placed it under the direct control of the Ilkhanate. The system of tumens was abolished, but the Mongols closely watched the Georgian administration in order to secure a steady flow of taxes and tributes from the subject peoples, who were also pressed into the Mongol armies. Georgians attended all major campaigns of the Ilkhanate and aristocrats' sons served in kheshig.[30]

The period between 1259 and 1330 was marked by the struggle of the Georgians against the Mongol Ilkhanate for full independence. The first anti-Mongol uprising started in 1259 under the leadership of King David Narin who in fact waged his war for almost thirty years. The Anti-Mongol strife went on under the Kings Demetrius II (c. 1270–1289) and David VIII (c. 1293–1311).

George V the Brilliant

Demetrius was executed by the Mongols in 1289, and the little prince George was carried to Samtskhe to be reared at the court of his maternal grandfather, Beka I Jaqeli. In 1299, the Ilkhanid khan Ghazan installed him as a rival ruler to George’s elder brother, the rebellious King David VIII. However, George’s authority did not extend beyond the Mongol-protected capital Tbilisi, so George was referred to during this period as "The Shadow King of Tbilisi". In 1302, he was replaced by his brother, Vakhtang III. After the death of both his elder brothers – David and Vakhtang – George became a regent for David’s son, George VI, who died underage in 1313, allowing George V to be crowned king for a second time. Having initially pledged his loyalty to the Il-khan Öljaitü, he began a program of reuniting the Georgian lands. In 1315, he led the Georgian auxiliaries to suppress an anti-Mongol revolt in Asia Minor, an expedition that would prove to be the last in which the Georgians fought in the Mongol ranks. In 1320, he drove the marauding Alans out of the town Gori and forced them back to the Caucasus Mountains.