Minarets of Al-Aqsa: Difference between revisions

Rescuing 3 sources and tagging 0 as dead. #IABot (v1.6.2) |

|||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

The first minaret, known as al-Fakhariyya Minaret, was built in 1278 on the southwestern corner of the mosque, on the orders of the Mamluk sultan [[Lajin]]. It was named after Fakhr al-Din al-Khalili, the father of Sharif al-Din Abd al-Rahman who supervised the building's construction. It was built in the traditional [[Syria]]n style, with a square-shaped base and shaft, divided by moldings into three floors above which two lines of [[muqarnas]] decorate the ''[[muezzin]]'s'' balcony. The niche is surrounded by a square chamber that ends in a lead-covered stone dome.<ref>Menashe, 2004, p.334.</ref> |

The first minaret, known as al-Fakhariyya Minaret, was built in 1278 on the southwestern corner of the mosque, on the orders of the Mamluk sultan [[Lajin]]. It was named after Fakhr al-Din al-Khalili, the father of Sharif al-Din Abd al-Rahman who supervised the building's construction. It was built in the traditional [[Syria]]n style, with a square-shaped base and shaft, divided by moldings into three floors above which two lines of [[muqarnas]] decorate the ''[[muezzin]]'s'' balcony. The niche is surrounded by a square chamber that ends in a lead-covered stone dome.<ref>Menashe, 2004, p.334.</ref> |

||

The second, known as the Ghawanima minaret, was built at the northwestern corner of the Noble Sanctuary in 1297–98 by architect Qadi Sharaf al-Din al-Khalili, also on the orders of the Sultan Lajin. Six stories high, it is the tallest minaret of the Noble Sanctuary.<ref>Brooke, Steven. ''Views of Jerusalem and the Holy Land''. Rizzoli, 2003. {{ISBN|0-8478-2511-6}}</ref> The tower is almost entirely made of stone, apart from a timber canopy over the ''[[muezzin]]'s'' balcony. Because of its firm structure, the Ghawanima minaret has been nearly untouched by earthquakes. The minaret is divided into several stories by stone molding and [[stalactite]] galleries. The first two stories are wider and form the base of the tower. The additional four stories are surmounted by a cylindrical drum and a bulbous dome. The stairway is externally located on the first two floors, but becomes an internal spiral structure from the third floor until it reaches the ''muezzin's'' balcony.<ref name="ADL1">[http://archnet.org/library/sites/one-site.jsp?site_id=5550 Ghawanima Minaret] Archnet Digital Library.</ref> |

The second, known as the Ghawanima minaret, was built at the northwestern corner of the Noble Sanctuary in 1297–98 by architect Qadi Sharaf al-Din al-Khalili, also on the orders of the Sultan Lajin. Six stories high, it is the tallest minaret of the Noble Sanctuary.<ref>Brooke, Steven. ''Views of Jerusalem and the Holy Land''. Rizzoli, 2003. {{ISBN|0-8478-2511-6}}</ref> The tower is almost entirely made of stone, apart from a timber canopy over the ''[[muezzin]]'s'' balcony. Because of its firm structure, the Ghawanima minaret has been nearly untouched by earthquakes. The minaret is divided into several stories by stone molding and [[stalactite]] galleries. The first two stories are wider and form the base of the tower. The additional four stories are surmounted by a cylindrical drum and a bulbous dome. The stairway is externally located on the first two floors, but becomes an internal spiral structure from the third floor until it reaches the ''muezzin's'' balcony.<ref name="ADL1">[http://archnet.org/library/sites/one-site.jsp?site_id=5550 Ghawanima Minaret] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131102224005/http://archnet.org/library/sites/one-site.jsp?site_id=5550 |date=2013-11-02 }} Archnet Digital Library.</ref> |

||

In 1329, [[Tankiz]]—the Mamluk governor of Syria—ordered the construction of a third minaret called the Bab al-Silsila Minaret located on the western border of the al-Aqsa Mosque. This minaret, possibly replacing an earlier [[Umayyad]] minaret, is built in the traditional Syrian square tower type and is made entirely out of stone.<ref>[http://archnet.org/library/sites/one-site.jsp?site_id=5548 Bab al-Silsila Minaret] Archnet Digital Library.</ref> Since the 16th-century, it has been tradition that the best ''muezzin'' ("reciter") of the ''[[adhan]]'' (the call to prayer), is assigned to this minaret because the first call to each of the five daily prayers is raised from it, giving the signal for the ''muezzins'' of mosques throughout Jerusalem to follow suit.<ref>Jacobs, 2009, p.106.</ref> |

In 1329, [[Tankiz]]—the Mamluk governor of Syria—ordered the construction of a third minaret called the Bab al-Silsila Minaret located on the western border of the al-Aqsa Mosque. This minaret, possibly replacing an earlier [[Umayyad]] minaret, is built in the traditional Syrian square tower type and is made entirely out of stone.<ref>[http://archnet.org/library/sites/one-site.jsp?site_id=5548 Bab al-Silsila Minaret] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131102224052/http://archnet.org/library/sites/one-site.jsp?site_id=5548 |date=2013-11-02 }} Archnet Digital Library.</ref> Since the 16th-century, it has been tradition that the best ''muezzin'' ("reciter") of the ''[[adhan]]'' (the call to prayer), is assigned to this minaret because the first call to each of the five daily prayers is raised from it, giving the signal for the ''muezzins'' of mosques throughout Jerusalem to follow suit.<ref>Jacobs, 2009, p.106.</ref> |

||

The last and most notable minaret was built in 1367, and is known as [[Minaret of Israel|Minaret al-Asbat]]. It is composed of a cylindrical stone shaft (built later by the [[Ottoman Empire|Ottoman]]s), which springs up from a rectangular Mamluk-built base on top of a triangular transition zone.<ref name="Asbat"/> The shaft narrows above the ''muezzin's'' balcony, and is dotted with circular windows, ending with a [[bulbous]] dome. The dome was reconstructed after the 1927 earthquake.<ref name="Asbat">[http://archnet.org/library/sites/one-site.jsp?site_id=5551 Bab al-Asbat Minaret] Archnet Digital Library.</ref> |

The last and most notable minaret was built in 1367, and is known as [[Minaret of Israel|Minaret al-Asbat]]. It is composed of a cylindrical stone shaft (built later by the [[Ottoman Empire|Ottoman]]s), which springs up from a rectangular Mamluk-built base on top of a triangular transition zone.<ref name="Asbat"/> The shaft narrows above the ''muezzin's'' balcony, and is dotted with circular windows, ending with a [[bulbous]] dome. The dome was reconstructed after the 1927 earthquake.<ref name="Asbat">[http://archnet.org/library/sites/one-site.jsp?site_id=5551 Bab al-Asbat Minaret] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110629165310/http://archnet.org/library/sites/one-site.jsp?site_id=5551 |date=2011-06-29 }} Archnet Digital Library.</ref> |

||

==Proposed fifth minaret== |

==Proposed fifth minaret== |

||

Revision as of 20:26, 31 January 2018

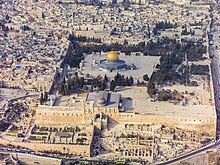

The Temple Mount has four minarets on the southern, northern and western sides.

Four minarets

The first minaret, known as al-Fakhariyya Minaret, was built in 1278 on the southwestern corner of the mosque, on the orders of the Mamluk sultan Lajin. It was named after Fakhr al-Din al-Khalili, the father of Sharif al-Din Abd al-Rahman who supervised the building's construction. It was built in the traditional Syrian style, with a square-shaped base and shaft, divided by moldings into three floors above which two lines of muqarnas decorate the muezzin's balcony. The niche is surrounded by a square chamber that ends in a lead-covered stone dome.[1]

The second, known as the Ghawanima minaret, was built at the northwestern corner of the Noble Sanctuary in 1297–98 by architect Qadi Sharaf al-Din al-Khalili, also on the orders of the Sultan Lajin. Six stories high, it is the tallest minaret of the Noble Sanctuary.[2] The tower is almost entirely made of stone, apart from a timber canopy over the muezzin's balcony. Because of its firm structure, the Ghawanima minaret has been nearly untouched by earthquakes. The minaret is divided into several stories by stone molding and stalactite galleries. The first two stories are wider and form the base of the tower. The additional four stories are surmounted by a cylindrical drum and a bulbous dome. The stairway is externally located on the first two floors, but becomes an internal spiral structure from the third floor until it reaches the muezzin's balcony.[3]

In 1329, Tankiz—the Mamluk governor of Syria—ordered the construction of a third minaret called the Bab al-Silsila Minaret located on the western border of the al-Aqsa Mosque. This minaret, possibly replacing an earlier Umayyad minaret, is built in the traditional Syrian square tower type and is made entirely out of stone.[4] Since the 16th-century, it has been tradition that the best muezzin ("reciter") of the adhan (the call to prayer), is assigned to this minaret because the first call to each of the five daily prayers is raised from it, giving the signal for the muezzins of mosques throughout Jerusalem to follow suit.[5]

The last and most notable minaret was built in 1367, and is known as Minaret al-Asbat. It is composed of a cylindrical stone shaft (built later by the Ottomans), which springs up from a rectangular Mamluk-built base on top of a triangular transition zone.[6] The shaft narrows above the muezzin's balcony, and is dotted with circular windows, ending with a bulbous dome. The dome was reconstructed after the 1927 earthquake.[6]

Proposed fifth minaret

There are no minarets in the eastern portion of the mosque. However, in 2006, King Abdullah II of Jordan announced his intention to build a fifth minaret overlooking the Mount of Olives. The King Hussein Minaret is planned to be the tallest structure in the Old City of Jerusalem.[7][8]

Gallery

-

The al-Fakhariyya Minaret is the first of four minarets of Al-Aqsa Mosque, constructed in 1278.

-

Bab al-Silsila minaret

-

The Ghawanima Minaret, 1900

References

- ^ Menashe, 2004, p.334.

- ^ Brooke, Steven. Views of Jerusalem and the Holy Land. Rizzoli, 2003. ISBN 0-8478-2511-6

- ^ Ghawanima Minaret Archived 2013-11-02 at the Wayback Machine Archnet Digital Library.

- ^ Bab al-Silsila Minaret Archived 2013-11-02 at the Wayback Machine Archnet Digital Library.

- ^ Jacobs, 2009, p.106.

- ^ a b Bab al-Asbat Minaret Archived 2011-06-29 at the Wayback Machine Archnet Digital Library.

- ^ Farrell, Stephen (14 October 2006). "Minaret that can't rise above politics". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Klein, Aaron (4 February 2007). "Israel allows minaret over Temple Mount". YNet. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)