Philanthropy: Difference between revisions

→Germany: ce |

→United States: copy ex "Philanthropy in the United States" |

||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

==United States == |

==United States == |

||

{{Main|Philanthropy in the United States}} |

|||

| ⚫ | [[Benjamin Franklin]] (1706 – 1790) |

||

The first corporation founded in the [[13 Colonies]] was , [[Harvard College]] (1636), designed primarily to them train young men for the clergy. A leading theorist was the Puritan theologian [[Cotton Mather]] (1662-1728), who in 1710 published a widely read essay, ''Bonifacius, or an Essay to Do Good.'' Mather worried that the original idealism had eroded, so he advocated philanthropic benefaction as a way of life. Though his context was Christian, his idea was also characteristically American and explicitly Classical, on the threshold of the Enlightenment. |

|||

| ⚫ | [[Benjamin Franklin]] (1706 – 1790) was an activist and theorist of American philanthropy. He was much influenced by [[Daniel Defoe]]'s ''An essay upon projects'' (1697) and [[Cotton Mather]]'s ''Bonifacius: an essay upon the good.'' (1710). Franklin specialized in motivating his fellow Philadelphians into projects for the betterment of the city, they set up the [[Library Company of Philadelphia]] (the first American subscription library), the fire department, the police force, street lighting and a hospital. A world-class physicist himself, he promoted scientific organizations including the Philadelphia Academy (1751)--which became the [[University of Pennsylvania]] – as well as the [[American Philosophical Society]] (1743) to enable scientific researchers from all 13 colonies to communicate.<ref>{{cite book|author=Robert T. Grimm, ed.|title=Notable American Philanthropists: Biographies of Giving and Volunteering|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vIdSBOiSazsC&pg=PA101|year=2002|pages=100–3}}</ref> |

||

By the 1820s, newly rich American businessmen were establishing philanthropic work, especially with respect to private colleges and hospitals. [[George Peabody]] (1795-1869) was the acknowledged father of modern philanthropy. A financier based in Baltimore and London, in the 1860s, he began to endowi libraries and museums in the United Statesl he also funded housing for poor people in London. He was the model for Andrew Carnegie and many others.<ref>{{cite book|author=Grimm, ed.|title=Notable American Philanthropists: Biographies of Giving and Volunteering|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vIdSBOiSazsC&pg=PA244|year=2002|pages=243–45}}</ref><ref>Elizabeth Schaaf, “George Peabody: His Life and Legacy, 1795–1869,” ''Maryland Historical Magazine'' 90#3 (1995) pp 268-285. </ref> |

By the 1820s, newly rich American businessmen were establishing philanthropic work, especially with respect to private colleges and hospitals. [[George Peabody]] (1795-1869) was the acknowledged father of modern philanthropy. A financier based in Baltimore and London, in the 1860s, he began to endowi libraries and museums in the United Statesl he also funded housing for poor people in London. He was the model for Andrew Carnegie and many others.<ref>{{cite book|author=Grimm, ed.|title=Notable American Philanthropists: Biographies of Giving and Volunteering|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vIdSBOiSazsC&pg=PA244|year=2002|pages=243–45}}</ref><ref>Elizabeth Schaaf, “George Peabody: His Life and Legacy, 1795–1869,” ''Maryland Historical Magazine'' 90#3 (1995) pp 268-285. </ref> |

||

Revision as of 05:50, 16 January 2018

Philanthropy means the love of humanity, in the sense of caring and nourishing, it involves both the benefactor in their identifying and exercising their values, and the beneficiary in their receipt and benefit from the service or goods provided. A conventional modern definition is "private initiatives, for the public good, focusing on quality of life," which combines an original humanistic tradition with a social scientific aspect developed in the 20th century. The definition also serves to contrast philanthropy with business endeavors, which are private initiatives for private good, e.g., focusing on material gain, and with government endeavors, which are public initiatives for public good, e.g., focusing on provision of public services.[1] A person who practices philanthropy is called a philanthropist.

Philanthropy has distinguishing characteristics separate from charity; not all charity is philanthropy, or vice versa, though there is a recognized degree of overlap in practice. A difference commonly cited is that charity aims to relieve the pain of a particular social problem, whereas philanthropy attempts to address the root cause of the problem—the difference between the proverbial gift of a fish to a hungry person, versus teaching them how to fish.

In the second century CE, Plutarch used the Greek concept of philanthrôpía to describe superior human beings. During the Roman Catholic Middle Ages, philanthrôpía was superseded by Caritas charity, selfless love, valued for salvation and escape from purgatory. Philanthropy was modernized by Sir Francis Bacon in the 1600s, who is largely credited with preventing the word from being owned by horticulture. Bacon considered philanthrôpía to be synonymous with "goodness", which correlated with the Aristotelian conception of virtue, as consciously instilled habits of good behavior. Samuel Johnson simply defined philanthropy as "love of mankind; good nature".[2] This definition still survives today and is often cited more gender-neutrally as the "love of humanity." However, it was Noah Webster who would more accurately reflect the word usage in American English.[3]

British philanthropy

In London prior to the 18th century, parochial and civic charities were typically established by bequests and operated by local church parishes (such as St Dionis Backchurch) or guilds (such as the Carpenters' Company). During the 18th century, however, "a more activist and explicitly Protestant tradition of direct charitable engagement during life" took hold, exemplified by the creation of the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge and Societies for the Reformation of Manners.[4]

In 1739, Thomas Coram, appalled by the number of abandoned children living on the streets of London, received a royal charter to establish the Foundling Hospital to look after these unwanted orphans in Lamb's Conduit Fields, Bloomsbury.[5] This was "the first children's charity in the country, and one that 'set the pattern for incorporated associational charities' in general."[5] The hospital "marked the first great milestone in the creation of these new-style charities."[4]

Jonas Hanway, another notable philanthropist of the era, established The Marine Society in 1756 as the first seafarer's charity, in a bid to aid the recruitment of men to the navy.[6] By 1763, the society had recruited over 10,000 men and it was incorporated by an Act of Parliament in 1772. Hanway was also instrumental in establishing the Magdalen Hospital to rehabilitate prostitutes. These organizations were funded by subscription and run as voluntary associations. They raised public awareness of their activities through the emerging popular press and were generally held in high social regard—some charities received state recognition in the form of the Royal Charter.

Philanthropists, such as anti-slavery campaigner William Wilberforce, began to adopt active campaigning roles, where they would champion a cause and lobby the government for legislative change. This included organized campaigns against the ill treatment of animals and children and the campaign that eventually succeeded in ending the slave trade throughout the British Empire at the turn of the 19th century.

During the 19th century, a profusion of charitable organizations was set up to alleviate the awful conditions of the working class in the slums. The Labourer's Friend Society, chaired by Lord Shaftesbury in the United Kingdom in 1830, was set up to improve working class conditions. This included the promotion of allotment of land to labourers for "cottage husbandry" that later became the allotment movement, and in 1844 it became the first Model Dwellings Company—an organization that sought to improve the housing conditions of the working classes by building new homes for them, while at the same time receiving a competitive rate of return on any investment. This was one of the first housing associations, a philanthropic endeavor that flourished in the second half of the nineteenth century, brought about by the growth of the middle class. Later associations included the Peabody Trust, and the Guinness Trust. The principle of philanthropic intention with capitalist return was given the label "five per cent philanthropy."[7][8]

United States

The first corporation founded in the 13 Colonies was , Harvard College (1636), designed primarily to them train young men for the clergy. A leading theorist was the Puritan theologian Cotton Mather (1662-1728), who in 1710 published a widely read essay, Bonifacius, or an Essay to Do Good. Mather worried that the original idealism had eroded, so he advocated philanthropic benefaction as a way of life. Though his context was Christian, his idea was also characteristically American and explicitly Classical, on the threshold of the Enlightenment.

Benjamin Franklin (1706 – 1790) was an activist and theorist of American philanthropy. He was much influenced by Daniel Defoe's An essay upon projects (1697) and Cotton Mather's Bonifacius: an essay upon the good. (1710). Franklin specialized in motivating his fellow Philadelphians into projects for the betterment of the city, they set up the Library Company of Philadelphia (the first American subscription library), the fire department, the police force, street lighting and a hospital. A world-class physicist himself, he promoted scientific organizations including the Philadelphia Academy (1751)--which became the University of Pennsylvania – as well as the American Philosophical Society (1743) to enable scientific researchers from all 13 colonies to communicate.[9]

By the 1820s, newly rich American businessmen were establishing philanthropic work, especially with respect to private colleges and hospitals. George Peabody (1795-1869) was the acknowledged father of modern philanthropy. A financier based in Baltimore and London, in the 1860s, he began to endowi libraries and museums in the United Statesl he also funded housing for poor people in London. He was the model for Andrew Carnegie and many others.[10][11]

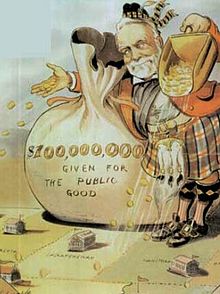

Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie (1835 – 1919) was the most influential leader of philanthropy on a national (rather than local) scale. After selling his giant steel company in the 1890s he devoted himself to establishing philanthropic organizations, and making direct contributions to many educational cultural and research institutions. His final and largest project was the Carnegie Corporation of New York, founded in 1911 with a $25 million endowment, later enlarged to $135 million. In all her gave away 90% of his fortune.[12]

The establishment of public libraries in the United States, Britain, and in dominions and colonies of the British Empire started a legacy that still operates on a daily basis for millions of people. The first Carnegie library opened in 1883 in Dunfermline, Scotland. His method was to build and stock a modern library,on condition that the local authority provided site and keep it in operation. In 1885, he gave $500,000 to Pittsburgh for a public library, and in 1886, he gave $250,000 to Allegheny City for a music hall and library, and $250,000 to Edinburgh, Scotland, for a free library. In total Carnegie gave $55 million to some 3,000 libraries, in 47 American states and overseas. As VanSlyck (1991) shows, the last years of the 19th century saw acceptance of the idea that libraries should be available to the American public free of charge. However the design of the idealized free library was at the center of a prolonged and heated debate. On one hand, the library profession called for designs that supported efficiency in administration and operation; on the other, wealthy philanthropists favored buildings that reinforced the paternalistic metaphor and enhanced civic pride. Between 1886 and 1917, Carnegie reformed both library philanthropy and library design, encouraging a closer correspondence between the two. Using the corporation as his model, Carnegie introduced many of the philanthropic practices of the modern foundation. At the same time, he rejected the rigid social and spatial hierarchy of the 19th-century library. In over 1,600 buildings that he funded and in hundreds of others influenced by its forms, Carnegie helped create an American public library type that embraced the planning principles espoused by librarians while extending a warmer welcome to the reading public.[13][14] There was some opposition, for example in Canada where anti-American and labour spokesman opposed his libraries, in fear of the influence of a powerful American, and in protest against his breaking a strike in 1892.[15]

Carnegie was in fact transforming his wealth into cultural power independent of Governmental or political controls. However he transcended national boundaries – he identified so much with Britain that at one point he thought of running for Parliament. In Canada and Britain he worked with like-minded local intellectual and cultural leaders who shared his basic values to promote an urgently needed Canadian or British cultural, intellectual, and educational infrastructure. In those countries, the rich industrialists rarely supported national philanthropy.[16] He also set up numerous permanent foundations, especially in pursuit of world peace, such as the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace formed in 1910 with a $10 million endowment.[17]

In Gospel of Wealth (1889), Carnegie proselytized the rich about their responsibilities to society.[18] His homily had an enormous influence in its day, and into the 21st century.[19][20] One early disciple was Phoebe Hearst, wife of the founder of the Hearst dynasty in San Francisco. She expanded the Carnegie approach to include women declaring that leisured women had a sacred duty to give to causes, especially progressive education and reform, that would benefit their communities, help those excluded or marginalized from America's mainstream, and advance women's careers as reformers and political leaders.[21]

John D Rockefeller

Other prominent American philanthropists of the early 20th century were John D. Rockefeller, Julius Rosenwald (1862-1932)[22][23] and Margaret Olivia Slocum Sage (1828-1918)[24]. Rockefeller (1839-1937) retired from business in the 1890s; he and his son John D. Rockefeller Jr. (1874-1960) made large-scale national philanthropy systematic especially regarding the study and application of modern medicine, higher, education and scientific research. Of the $530 million the elder Rockefeller gave away, $450 million went to medicine.[25] Their top advisor Frederick Taylor Gates designed several very large philanthropies that were staffed by experts who designed ways to attack problems systematically rather than let the recipients decide how to deal with the problem.[26]

Local millionaires

Albert Shaw editor of the magazine American Review of Reviews in 1893 examined philanthropic activities of millionaires in several major cities. The highest rate was Baltimore where 49% of the millionaires were active givers; New York City ranked last. Cincinnati millionaires favored musical and artistic ventures; Minneapolis millionaires gave to the state university in the public library; Philadelphians often gave to overseas relief, and the education of blacks and Indians. Boston had a weak profile, apart from donations to Harvard and the Massachusetts General Hospital. [27]

Europe

In 1863, the Swiss businessman Henry Dunant used his personal fortune to fund the Geneva Society for Public Welfare, which became the International Committee of the Red Cross. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, Dunant personally led Red Cross delegations that treated soldiers. He shared the first Nobel Peace Prize for this work in 1901.[28][29]

In France, the Pasteur Institute had a monopoly of specialized microbiological knowledge allowed it to raise money for serum production from both private and public sources, walking the line between a commercial pharmaceutical venture and a philanthropic enterprise.[30]

Germany

The history of modern philanthropy the European Continent is especially important in the case of Germany, which became a model for others, especially regarding the welfare state. The princes and in the various Imperial states continued traditional efforts, such as monumental buildings, parks and art collections. Starting in the early 19th century, the rapidly emerging middle classes made local philanthropy a major endeavor to establish their legitimate role in shaping society, in contradistinction to the aristocracy and the military. They concentrated on support for social welfare institutions, higher education, and cultural institutions, as well as some efforts to alleviate the hardships of rapid industrialization. The bourgeoisie (upper-middle-class) was defeated in its effort to it gain political control in 1848, but they still had enough money and organizational skill that could be employed through philanthropic agencies to provide an alternative powerbase for their world view.[31] Religion was a divisive element in Germany, as the Protestants, Catholics and Jews used alternative philanthropic strategies. The Catholics, for example, continued their medieval practice of using financial donations in their wills to lighten their punishment in purgatory after death. The Protestants did not believe in purgatory, but made a strong commitment to the improvement of their communities here and now. Conservative Protestants Raised concerns about deviant sexuality, alcoholism and socialism, as well as illegitimate births. They used philanthropy to eradicate social evils that were seen as utterly sinful.[32][33] All the religious groups used financial endowments, which multiplied in the number and wealth as Germany grew richer. Each was devoted to a specific benefit to that religious community. Each had a board of trustees; these were laymen who donated their time to public service. Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, an upper class Junker, used his state-sponsored philanthropy, in the form of his invention of the modern welfare state, to neutralize the political threat posed by the socialistic labor unions.[34] The middle classes, however, made the most use of the new welfare state, in terms of heavy use of museums, gymnasiums (high schools), universities, scholarships, and hospitals. For example state funding for universities and gymnasiums covered only a fraction of the cost; private philanthropy became the essential ingredient. 19th century Germany was even more oriented toward civic improvement then Britain or the United States, when measured in terms of voluntary private funding for public purposes. Indeed such German institutions as the kindergarten, the research university, and the welfare state became models copied by the Anglo-Saxons. [35] The heavy human and economic losses of the First World War, the financial crises of the 1920s, as well as the Nazi regime and other devastation by 1945, seriously undermined and weakened the opportunities for widespread philanthropy in Germany. The civil society so elaborately build up in the 19th century was practically dead by 1945. However, by the 1950s, as the "economic miracle" was restoring German prosperity, the old aristocracy was defunct, and middle-class philanthropy started to return to importance. [36]

21st century efforts

Studies by The Chronicle of Philanthropy have indicated that the rich—those making over $100,000 a year—give a smaller share of their income[clarification needed] to charity (4.2% on average) than those making $50,000–$100,000 a year.[37][38]

Trends in philanthropy have been affected in various ways by a technological and cultural change. Today, many donations are made through the Internet (see also donation statistics).[39]

Organizations supporting

This section needs expansion with: further coverage of modern extant organizations that have long histories of studying philanthropy and analyzing its societal roles—such as the CUNY and Duke efforts pioneered in the 80s, remnants of the Rockefeller-funded postwar Japanese efforts, etc., see Talk—I'm with concomitant reduction of space for the Lilly School (and reigning it of its clear advert-style partiality). You can help by adding to it. (January 2016) |

A variety of organizations that have been created over the decades to study, support, and evaluate practical philanthropic endeavors and ideas exist today and continue research into philanthropy, analysis of its trends, and student-training for its occupations and further study.

See also

- List of philanthropists

- List of wealthiest charitable foundations

- Charitable organization

- Foundation (charity)

- Non-profit organization

- Venture philanthropy

References

- ^ Robert McCully. Philanthropy Reconsidered (2009) p 13

- ^ Johnson, S. (1979). A dictionary of the English language. London: Times Books.

- ^ "Mitchell Kutney: Philanthropy is what sustains the charitable sector, not money". Blue & Green Tomorrow. 2013-06-18. Retrieved 2014-11-08.[better source needed]

- ^ a b "Background - Associational Charities". London Lives. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ^ a b "The London Foundling Hospital". victorianweb.org. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ^ N. A. M. Rodger, The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain 1649–1815 (New York: W. W. Norton & Company: 2004), 313.

- ^ Siegel, Fred (1974). "Five Per Cent Philanthropy: An Account of Housing in Urban Areas Between 1840 and 1914. By John Nelson Tarn… [Book Review]". The Journal of Economic History. 34 (4, December): 1061f. doi:10.1017/S0022050700089683. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ^ Tarn, John Nelson (1973). Five Per Cent Philanthropy: An Account of Housing in Urban Areas Between 1840 and 1914. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. xiv, 23, and passim. ISBN 0521085063. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ^ Robert T. Grimm, ed. (2002). Notable American Philanthropists: Biographies of Giving and Volunteering. pp. 100–3.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Grimm, ed. (2002). Notable American Philanthropists: Biographies of Giving and Volunteering. pp. 243–45.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Elizabeth Schaaf, “George Peabody: His Life and Legacy, 1795–1869,” Maryland Historical Magazine 90#3 (1995) pp 268-285.

- ^ Joseph Frazier Wall, Andrew Carnegie (1970) pp 882-84.

- ^ Abigail A. VanSlyck, "'The Utmost Amount of Effectiv Accommodation': Andrew Carnegie and the Reform of the American Library", Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians (1991) 50#4 pp. 359–383 in JSTOR.

- ^ Peter Mickelson, . "American society and the public library in the thought of Andrew Carnegie." Journal of Library History 10.2 (1975): 117-138.

- ^ Susan Goldenberg, "Dubious Donations," Beaver" (May 2008) 88#2 pp 34-40

- ^ Jeffrey D. Brison, Rockefeller, Carnegie, and Canada: American Philanthropy and the Arts and Letters in Canada (McGill-Queen's UP, 2005)

- ^ David S. Patterson,"Andrew Carnegie's quest for world peace." Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 114.5 (1970): 371-383. online

- ^ Andrew Carnegie, "Wealth." The North American Review Vol. 148, No. 391 (June, 1889), pp. 653-664 online

- ^ Michael Moody; Beth Breeze, eds. (2016). The Philanthropy Reader. Taylor & Francis. p. 171.

{{cite book}}:|author2=has generic name (help) - ^ David Callahan, The Givers: Wealth, Power, and Philanthropy in a New Gilded Age (2017); p 218 tells how Warren Buffett gave a copy of Carnegie's essay to Bill Gates.

- ^ Alexandra M. Nickliss, "Phoebe Apperson Hearst's" Gospel of Wealth," 1883––1901." Pacific Historical Review 71.4 (2002): 575-605.

- ^ Grimm, ed. (2002). Notable American Philanthropists. pp. 277–79.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Peter M. Ascoli, Julius Rosenwald: The Man Who Built Sears, Roebuck and Advanced the Cause of Black Education in the American South (2006)

- ^ Ruth Crocker, Mrs. Russell Sage Women's Activism and Philanthropy in Gilded Age and Progressive Era America (2003)

- ^ Peter J. Johnson and John Ensor Harr, The Rockefeller Century: Three Generations of America's Greatest Family (1988)

- ^ Dwight Burlingame (2004). Philanthropy in America: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia, vol 2. ABC-CLIO. p. 419.

- ^ Robert H. Bremner, American philanthropy (U of Chicago Press, 1988) p 109; full text of Albert Shaw, "American Millionaires and Their Public Gifts," Review of Reviews (February 1893), pp 48-60 [https://sites.hks.harvard.edu/fs/phall/04.%20Bostonization.pdf is online here

- ^ "Henry Dunant". nndb.com. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ^ David P. Forsythe, The Humanitarians: The International Committee of the Red Cross (2005).

- ^ Jonathan Simon, "The origin of the production of diphtheria antitoxin in France, between philanthropy and commerce." Dynamis: Acta Hispanica ad Medicinae Scientiarumque Historiam Illustrandam 27 (2007): 63-82. online

- ^ Thomas Adam, Philanthropy, Civil Society, and the State in German history, 1815-1989 (2016).

- ^ Andrew Lees, "Deviant Sexuality and Other 'Sins': The Views of Protestant Conservatives in Imperial Germany." German Studies Review 23.3 (2000): 453-476.

- ^ Andrew Lees, Cities, Sin and Social Reform in Imperial Germany (2002).

- ^ Dimitris N. Chorafas (2016). Education and Employment in the European Union: The Social Cost of Business. Routledge. p. 255.

- ^ Adam, Philanthropy, pp 1-7.

- ^ Adam, Philanthropy, pp 142-73.

- ^ Frank, Robert (August 20, 2012). "The Rich Are Less Charitable Than the Middle Class: Study". CNBC. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ^ Kavoussi, Bonnie. "Rich People Give A Smaller Share Of Their Income To Charity Than Middle-Class Americans Do". The Huffington Post. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ^ "The 2011 Online Giving Report, presented by Steve MacLaughlin, Jim O'Shaughnessy, and Allison Van Diest" (PDF). blackbaud.com. February 2012. Retrieved January 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)

Further reading

- Adam, Thomas. Philanthropy, Patronage, and Civil Society: Experiences from Germany, Great Britain, and North America (2008)

- Bremner, Robert H. "Private philanthropy and public needs: Historical perspective." in Commission on Private Philanthropy and Public Needs, Research Papers (1977) vol 1 pp 89-113.

- Burlingame, D.F. Ed. (2004). Philanthropy in America: A comprehensive historical encyclopaedia (3 vol. ABC Clio).

- Curti, Merle E. American philanthropy abroad: a history (Rutgers UP, 1963).

- Grimm, Robert T. Notable American Philanthropists: Biographies of Giving and Volunteering (2002) excerpt

- Harvey, Charles, et al. "Andrew Carnegie and the foundations of contemporary entrepreneurial philanthropy." Business History 53.3 (2011): 425-450. online

- Hitchcock, William I. (2014) "World War I and the humanitarian impulse." The Tocqueville Review/La revue Tocqueville 35.2 (2014): 145-163.

- Ilchman, Warren F. et al. Philanthropy in the World's Traditions (1998) Examines philanthropy in Buddhist, Islamic, Hindu, Jewish, and Native American religious traditions and in cultures from Latin America, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and Asia. online

- Jordan, W.K. Philanthropy in England, 1480-1660: A Study of the Changing Pattern of English Social Aspirations (1959) online

- Kiger, Joseph C. (2011) Philanthropists and foundation globalization (Transaction Publishers).

- Taylor, Marilyn L.; Robert J. Strom; David O. Renz (2014). Handbook of Research on Entrepreneurs: Engagement in Philanthropy: Perspectives. Edward Elgar. pp. 1–8.

- Reich, Rob, Chiara Cordelli, and Lucy Bernholz, eds. Philanthropy in democratic societies: History, institutions, values (U of Chicago Press, 2016).

- Zunz, Olivier. Philanthropy in America: A history (Princeton UP, 2014).

External links

- NPtrust.org, History of Philanthropy, 1601–present compiled and edited by National Philanthropic Trust