Common Security and Defence Policy: Difference between revisions

| Line 76: | Line 76: | ||

==Permanent Structured Cooperation== |

==Permanent Structured Cooperation== |

||

The [[European Defence Initiative]] was a proposal for enhanced [[European Union]] defence cooperation presented by France, Germany, Belgium and Luxembourg in Brussels on 29 April 2003, before the extension of the coverage of the enhanced cooperation procedure to defence matters. The [[Treaty of Lisbon]] added the possibility for "those Member States whose military capabilities fulfill higher criteria and which have made more binding commitments to one another in this area with a view to the most demanding missions [to] establish permanent structured cooperation within the Union framework".<ref name="PSCD">{{cite web|url=http://register.consilium.europa.eu/pdf/en/08/st06/st06655.en08.pdf|title=Article 42(6), Article 43(1), Article 46, Protocol 10 of the amended Treaty on European Union|publisher=}}</ref> |

|||

Those states shall notify their intention to [[Council of the European Union|the Council]] and to the [[High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy|High Representative]]. The Council then adopts, by [[Voting in the Council of the European Union|qualified majority]] a decision establishing permanent structured cooperation and determining the list of participating Member States. Any other member state, that fulfills the criteria and wishes to participate, can join the PSCD following the same procedure, but in the voting for the decision will participate only the states already part of the PSCD. If a participating state no longer fulfills the criteria a decision suspending its participation is taken by the same procedure as for accepting new participants, but excluding the concerned state from the voting procedure. If a participating state wishes to withdraw from PSCD it just notifies [[Council of the European Union|the Council]] to remove it from the list of participants. All other decisions and recommendations of [[Council of the European Union|the Council]] concerning PSCD issues unrelated to the list of participants are taken by [[unanimity]] of the participating states.<ref name="PSCD"/> |

|||

The criteria established in the PSCD Protocol are the following:<ref name="PSCD"/> |

|||

* co-operate and harmonise requirements and pool resources in the fields related to defence equipment acquisition, research, funding and utilisation, notably the programs and initiatives of the [[European Defence Agency]] (e.g. [[European Union defence procurement#Code of Conduct on Defence Procurement|Code of Conduct on Defence Procurement]]) |

|||

* capacity to supply, either at [[Military of the European Union#Militaries of Member States|national level]] or as a component of [[Battlegroup of the European Union|multinational force groups]], targeted combat units for the [[CSDP missions|missions planned]], structured at a [[Military tactics|tactical level]] as a [[Battlegroup (army)|battle group]], with [[Command and control|support]] elements including transport ([[airlift]], [[sealift]]) and [[Military logistics|logistics]], within a period of five to 30 days, in particular in response to requests from the United Nations Organization, and which can be sustained for an initial period of 30 days and be extended up to at least 120 days. |

|||

* capable of carrying out in the above timeframes the tasks of joint [[disarmament]] operations, [[Humanitarian crisis|humanitarian]] and [[rescue]] tasks, military advice and assistance tasks, conflict prevention and [[peace-keeping]] tasks, tasks of combat forces in crisis management, including [[Peacebuilding|peace-making]] and post-conflict stabilisation<ref name="PSCD"/> |

|||

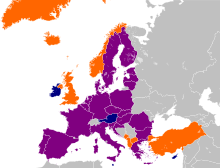

On 7 September 2017 an agreement was made between EU foreign affairs ministers to move forward with PESCO with 10 initial projects. Although the details are still to be established, the aim would be for it to be as inclusive of member states as possible and is anticipated to be activated in December 2017.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://seenews.com/news/romania-to-join-eus-defence-initiative-pesco-587373|title=Romania to join EU’s defence initiative PESCO|first=Nicoleta|last=Banila|work=SeeNews|date=2017-10-17|access-date=2017-12-07|dead-url=no|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171018190554/https://seenews.com/news/romania-to-join-eus-defence-initiative-pesco-587373|archive-date=2017-10-18}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.eu2017.ee/news/press-releases/PESCO|title=EU defence ministers: defence cooperation needs to be brought to a new level|date=2017-09-07|access-date=2017-12-07|publisher=Estonian Presidency of the Council of the European Union|dead-url=no|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171018134113/https://www.eu2017.ee/news/press-releases/PESCO|archive-date=2017-10-18}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headQuarters-homepage_en/31832/Permanent%20Structured%20Cooperation%20on%20defence%20could%20be%20launched%20by%20end%202017|title=Permanent Structured Cooperation on defence could be launched by end 2017|date=2017-09-08|access-date=2017-12-07|publisher=[[European External Action Service]]|dead-url=no|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170912233945/https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage_en/31832/Permanent%20Structured%20Cooperation%20on%20defence%20could%20be%20launched%20by%20end%202017|archive-date=2017-09-12}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.praguemonitor.com/2017/10/12/czech-government-join-pesco-defence-project|title=Czech government to join PESCO defence project|date=2017-10-12|access-date=2017-12-07|work=Prague Daily Monitor|dead-url=no|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171012093704/http://www.praguemonitor.com/2017/10/12/czech-government-join-pesco-defence-project|archive-date=2017-10-12}}</ref> The agreement was signed on 13 November by 23 of the 28 members states. Ireland and Portugal have notified the High Representative and the Council of the European Union of their intentions to join PESCO. <ref>{{citeweb|title=Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) - Council Decision - preparation for the adoption|url=http://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-15511-2017-INIT/en/pdf|date=2017-12-08|access-date=2017-12-12|work=Council of the European Union}}</ref> Denmark did not participate as it has an [[Danish opt-outs from the European Union|opt-out]] from the [[Common Security and Defence Policy]], nor did the United Kingdom, which is scheduled to [[Brexit|withdraw from the EU]] in 2019 .<ref name= "EU paves way">{{cite news|url=http://www.dw.com/en/pesco-eu-paves-way-to-defense-union/a-41360236|title=PESCO: EU paves way to defense union|date=2017-11-13|accessdate=2017-11-16|work=[[Deutsche Welle]]|dead-url=no|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171118173325/http://www.dw.com/en/pesco-eu-paves-way-to-defense-union/a-41360236|archive-date=2017-11-18}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/13/world/europe/eu-military-force.html|title=E.U. Moves Closer to a Joint Military Force|last=Erlanger|first=Steven|date=2017-11-13|work=The New York Times|access-date=2017-11-13|language=en-US|issn=0362-4331|dead-url=no|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171113205230/https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/13/world/europe/eu-military-force.html|archive-date=2017-11-13}}</ref> Malta opted-out as well.<ref>{{citenews|url=https://www.timesofmalta.com/articles/view/20171211/local/malta-among-three-countries-opting-out-of-eus-new-defence-agreement.665421|title=Malta among three countries opting out of EU's new defence agreement|work=Times of Malta|date=2017-12-11|access-date=2017-12-12|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171212065330/https://www.timesofmalta.com/articles/view/20171211/local/malta-among-three-countries-opting-out-of-eus-new-defence-agreement.665421|archive-date=2017-12-12| deadurl=no}}</ref><ref>{{citenews|url=http://www.dw.com/en/twenty-five-eu-states-sign-pesco-defense-pact/a-41741828|title=Twenty-five EU states sign PESCO defense pact|work=Deutsche Welle|date=2017-12-11|access-date=2017-12-12|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171212145317/http://www.dw.com/en/twenty-five-eu-states-sign-pesco-defense-pact/a-41741828|archive-date=2017-12-12}}</ref> |

|||

==Missions and Operations== |

==Missions and Operations== |

||

{{Main|Military operations of the European Union}} |

{{Main|Military operations of the European Union}} |

||

Revision as of 09:58, 15 December 2017

| This article is part of a series on |

|

|---|

|

|

The Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP), formerly known as the European Security and Defence Policy (ESDP), is a major element of the Common Foreign and Security Policy of the European Union (EU) and is the domain of EU policy covering defence and military aspects, as well as civilian crisis management. The ESDP was the successor of the European Security and Defence Identity under NATO, but differs in that it falls under the jurisdiction of the European Union itself, including countries with no ties to NATO.

Formally, the Common Security and Defence Policy is the domain of the European Council, which is an EU institution, whereby the heads of member states meet. Nonetheless, the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, currently Federica Mogherini, also plays a significant role. As Chairperson of the external relations configuration of the Council, the High Representative prepares and examines decisions to be made before they are brought to the Council.

European security policy has followed several different paths during the 1990s, developing simultaneously within the Western European Union, NATO and the European Union itself.

History

Background 1945–1954

This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Excessive passive voice, grammar issues, and a couple long sentences. (August 2015) |

Earlier efforts were made to have a common European security and defence policy. The 1947 Treaty of Dunkirk between UK and France was a European alliance and mutual assistance agreement after WWII. This agreement was transferred in 1948 to the military Article 4 of the Treaty of Brussels which included the BeNeLux countries. To reach the treaty goals the Western Union Defence Organization was set up 1948 with an allied European command structure under British Field Marshal Montgomery. In 1949 the United States and Canada joined the alliance and its mutual defence agreements through the North Atlantic Treaty with its Article 5 mutual defence clause which differed from the Brussels Treaty as it did not necessarily include military response. In 1950 the European Defence Community (EDC), similar in nature to European Coal and Steel Community, was proposed but failed ratification in the French parliament. The military Western Union Defence Organization was during the 1950–1953 Korean War augmented to become the North Atlantic Treaty Organization of the cold war. The failure to establish the EDC resulted in the 1954 amendment of the Treaty of Brussels at the London and Paris Conferences which in replacement of EDC established the political Western European Union (WEU) out of the earlier established Western Union Defence Organization and included West Germany and Italy in both WEU and NATO as the conference ended the occupation of West Germany and the defence aims had shifted from Germany to the Soviet Union.

Petersberg tasks

In 1992, the Western European Union adopted the Petersberg tasks, designed to cope with the possible destabilising of Eastern Europe. The WEU itself had no standing army but depended on cooperation between its members. Its tasks ranged from the most modest to the most robust, and included:[1]

- Humanitarian and rescue tasks

- Peacekeeping tasks

- Tasks for combat forces in crisis management, including peacemaking

WEU-NATO relationship and the Berlin agreement

At the 1996 NATO ministerial meeting in Berlin, it was agreed that the Western European Union (WEU) would oversee the creation of a European Security and Defence Identity within NATO structures.[2] The ESDI was to create a European 'pillar' within NATO, partly to allow European countries to act militarily where NATO wished not to, and partly to alleviate the United States' financial burden of maintaining military bases in Europe, which it had done since the Cold War. The Berlin agreement allowed European countries (through the WEU) to use NATO assets if it so wished (this agreement was later amended to allow the European Union to conduct such missions, the so-called Berlin-plus arrangement).

Incorporation of the Petersberg tasks and the WEU in the EU

The European Union incorporated the same Petersberg tasks within its domain with the Amsterdam Treaty. The treaty signalled the progressive framing of a common security and defence policy based on the Petersberg tasks. In 1998, traditional British reluctance to such a plan changed into endorsement after a bilateral declaration of French President Jacques Chirac and the British Prime Minister Tony Blair in St. Malo, where they stated that "the Union must have the capacity for autonomous action, backed up by credible military forces, the means to decide to use them, and a readiness to do so, in order to respond to international crises".

In June 1999, the Cologne European Council decided to incorporate the role of the Western European Union within the EU, eventually shutting down the WEU. The Cologne Council also appointed Javier Solana as the High Representative for Common Foreign and Security Policy to help progress both the CFSP and the ESDP.

Helsinki Headline Goal

The European Union made its first concrete step to enhance military capabilities, in line with the ESDP, in 1999 when its member states signed the Helsinki Headline Goal. They include the creation of a catalogue of forces, the 'Helsinki Force Catalogue', to be able to carry out the so-called “Petersberg Tasks”. The EU launched the European Capabilities Action Plan (ECAP) at the Laeken Summit in December 2001. However, it became clear that the objectives outlined in the Helsinki Headline Goal were not achievable quickly. In May 2004, EU defence ministers approved "Headline Goal 2010", extending the timelines for the EU's projects. However, it became clear that the objectives cannot be achieved by this date too. French Foreign Minister Alain Juppé espressed his desperation: “The common security and defense policy of Europe? It is dead.”[3]

Berlin Plus agreement and the relationship with NATO

Concerns were voiced that an independent European security pillar might result in a declining importance of NATO as a transatlantic forum. In response to St. Malo, the former US-Secretary of State Madeleine Albright put forth the three famous D’s, which outline American expectations towards ESDP to this day: no duplication of what was done effectively under NATO, no decoupling from the US and NATO, and no discrimination against non-EU members such as Turkey.

In the joint EU-NATO declaration of 2002, the six founding principles included partnership—for example, crisis management activities should be "mutually reinforcing"—effective mutual consultation and cooperation, equality and due regard for ‘the decision-making autonomy and interests’ of both EU and NATO, and ‘coherent and mutually reinforcing development of the military capability requirements common to the two organisations’. In institutional terms, the partnership is reflected in particular by the "Berlin plus agreement" from March 2003, which allows the EU to use NATO structures, mechanisms and assets to carry out military operations if NATO declines to act. Furthermore, an agreement has been signed on information sharing between the EU and NATO, and EU liaison cells are now in place at SHAPE (NATO’s strategic nerve centre for planning and operations) and NATO’s Joint Force Command in Naples.

A phrase that is often used to describe the relationship between the EU forces and NATO is "separable, but not separate":[4] the same forces and capabilities form the basis of both EU and NATO efforts, but portions can be allocated to the European Union if necessary. The right of first refusal governs missions: the EU may only act if NATO first decides not to.

European Security Strategy

The European Security Strategy was written in 2003 and was the policy document that guided for a time the European Union's international security strategy. Its headline reads: "A Secure Europe In A Better World". The document was approved by the European Council held in Brussels on 12 December 2003 and drafted under the responsibilities of the EU High Representative for Common Foreign and Security Policy CFSP Javier Solana. With the emergence of the ESDP, it is the first time that Europe has formulated a joint security strategy. It can be considered a counterpart to the National Security Strategy of the United States.

The document starts out with the declaration that "Europe has never been so prosperous, so secure nor so free". Its conclusion is that "The world is full of new dangers and opportunities". Along these lines, it argues that in order to ensure security for Europe in a globalising world, multilateral cooperation within Europe and abroad is to be the imperative, because "no single nation is able to tackle today's complex challenges". As such the ESS identifies a string of key threats Europe needs to deal with: terrorism, proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, regional conflict, failed states, and organised crime.[5]

The document was followed by the 2008 Report of the Implementation of the European Security Strategy: Providing Security in a Changing World. It concludes with the admonition "To build a secure Europe in a better world, we must do more to shape events. And we must do it now."[6]

European Defence Agency

The European Defence Agency (EDA) was established in July 2004 and is based in Brussels. It supports the EU Member States in improving their military capabilities in order to complete CSDP targets as set out in the European Security Strategy. In that capacity, it makes proposals, coordinates, stimulates collaboration, and runs projects. The Member States themselves, however, remain in charge of their defence policies, planning and investment. Four strategies form the framework to guide the activities of the Agency and its 26 participating Member States: 1) the Capability Development Plan (CDP), 2) the European Defence Research & Technology; 3) the European Armaments Cooperation (EAC) and 4) the European Defence Technological and Industrial Base (EDTIB).

European Union Institute for Security Studies

The EU Institute for Security Studies (EU-ISS) was inaugurated in January 2002 and is based in Paris. Although an EU agency, it is an autonomous think tank that researches EU-relevant security issues. The research results are published in papers, books, reports, policy briefs, analyses and newsletters. In addition, the EU-ISS convenes seminars and conferences on relevant issues that bring together EU officials, national experts, decision-makers and NGO representatives from all Member States.

European Union Satellite Centre

The European Union Satellite Centre was incorporated as an agency of the European Union (EU) on 1 January 2002. It is located in Torrejón de Ardoz, in the vicinity of Madrid, Spain. The centre supports the decision-making of the European Union in the field of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP), including crisis management missions and operations, by providing products and services resulting from the exploitation of relevant space assets and collateral data, including satellite and aerial imagery, and related services.

Treaty of Lisbon

The 2009 Treaty of Lisbon renamed the ESDP to Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP). The post of High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy has been created (superseding the High Representative for the Common Foreign and Security Policy and European Commissioner for External Relations and European Neighbourhood Policy). Unanimous decisions in the Council of the European Union continue to instruct the EU foreign policy and CSDP matters became available to enhanced co-operation.

- The common security and defence policy shall include the progressive framing of a common Union defence policy. This will lead to a common defence, when the European Council, acting unanimously, so decides. It shall in that case recommend to the member States the adoption of such a decision in accordance with their respective constitutional requirements.

- The policy of the Union in accordance with this article shall not prejudice the specific character of the security and defence policy of certain member states, which see their common defence realised in the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, under the North Atlantic Treaty, and be compatible with the common security and defence policy established within that framework.

Lisbon also led to the termination of the Western European Union in 2010 as, with the solidarity clause (deemed to supersede the WEU's military mutual defence clause) and the expansion of the CSDP, the WEU became redundant. All its remaining activities are to be wound up or transferred to the EU by June 2011.[7]

Lisbon extends the enhanced co-operation mechanism to defence issues and also envisions the establishment of a Permanent Structured Cooperation in Defence.

Permanent Structured Cooperation

The European Defence Initiative was a proposal for enhanced European Union defence cooperation presented by France, Germany, Belgium and Luxembourg in Brussels on 29 April 2003, before the extension of the coverage of the enhanced cooperation procedure to defence matters. The Treaty of Lisbon added the possibility for "those Member States whose military capabilities fulfill higher criteria and which have made more binding commitments to one another in this area with a view to the most demanding missions [to] establish permanent structured cooperation within the Union framework".[8]

Those states shall notify their intention to the Council and to the High Representative. The Council then adopts, by qualified majority a decision establishing permanent structured cooperation and determining the list of participating Member States. Any other member state, that fulfills the criteria and wishes to participate, can join the PSCD following the same procedure, but in the voting for the decision will participate only the states already part of the PSCD. If a participating state no longer fulfills the criteria a decision suspending its participation is taken by the same procedure as for accepting new participants, but excluding the concerned state from the voting procedure. If a participating state wishes to withdraw from PSCD it just notifies the Council to remove it from the list of participants. All other decisions and recommendations of the Council concerning PSCD issues unrelated to the list of participants are taken by unanimity of the participating states.[8]

The criteria established in the PSCD Protocol are the following:[8]

- co-operate and harmonise requirements and pool resources in the fields related to defence equipment acquisition, research, funding and utilisation, notably the programs and initiatives of the European Defence Agency (e.g. Code of Conduct on Defence Procurement)

- capacity to supply, either at national level or as a component of multinational force groups, targeted combat units for the missions planned, structured at a tactical level as a battle group, with support elements including transport (airlift, sealift) and logistics, within a period of five to 30 days, in particular in response to requests from the United Nations Organization, and which can be sustained for an initial period of 30 days and be extended up to at least 120 days.

- capable of carrying out in the above timeframes the tasks of joint disarmament operations, humanitarian and rescue tasks, military advice and assistance tasks, conflict prevention and peace-keeping tasks, tasks of combat forces in crisis management, including peace-making and post-conflict stabilisation[8]

On 7 September 2017 an agreement was made between EU foreign affairs ministers to move forward with PESCO with 10 initial projects. Although the details are still to be established, the aim would be for it to be as inclusive of member states as possible and is anticipated to be activated in December 2017.[9][10][11][12] The agreement was signed on 13 November by 23 of the 28 members states. Ireland and Portugal have notified the High Representative and the Council of the European Union of their intentions to join PESCO. [13] Denmark did not participate as it has an opt-out from the Common Security and Defence Policy, nor did the United Kingdom, which is scheduled to withdraw from the EU in 2019 .[14][15] Malta opted-out as well.[16][17]

Missions and Operations

In the EU terminology, civilian CSDP interventions are called ‘missions’, regardless of whether they have an executive mandate such as EULEX Kosovo or a non-executive mandate (all others). Military interventions, however, can either have an executive mandate such as for example Operation ATALANTA in which case they are referred to as ‘operations’ and are commanded at two-star level; or non-executive mandate (e.g. EUTM Somalia)in which case they are called ‘missions’ and are commanded at one-star level.

The first deployment of European troops under the ESDP, following the 1999 declaration of intent, was in March 2003 in the Republic of Macedonia. "EUFOR Concordia" used NATO assets and was considered a success and replaced by a smaller police mission, EUPOL Proxima, later that year. Since then, there have been other small police, justice and monitoring missions. As well as the Republic of Macedonia, the EU has maintained its deployment of peacekeepers in Bosnia and Herzegovina, as part of EUFOR Althea mission.[18]

Between May and September 2003 EU troops were deployed to the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) during "Operation Artemis" under a mandate given by UN Security Council Resolution 1484 which aimed to prevent further atrocities and violence in the Ituri Conflict and put the DRC's peace process back on track. This laid out the "framework nation" system to be used in future deployments. The EU returned to the DRC during July–November 2006 with EUFOR RD Congo, which supported the UN mission there during the country's elections.

Geographically, EU missions outside the Balkans and the DRC have taken place in Georgia, Indonesia, Sudan, Palestine, and Ukraine-Moldova. There is also a judicial mission in Iraq (EUJUST Lex). On 28 January 2008, the EU deployed its largest and most multi-national mission to Africa, EUFOR Tchad/RCA.[19] The UN-mandated mission involves troops from 25 EU states (19 in the field) deployed in areas of eastern Chad and the north-eastern Central African Republic in order to improve security in those regions. EUFOR Tchad/RCA reached full operation capability in mid-September 2008, and handed over security duties to the UN (MINURCAT mission) in mid-March 2009.[20].

The EU launched its first maritime CSDP operation on 12 December 2008 (Operation ATALANTA). The concept of the European Union Naval Force (EU NAVFOR) was created on the back of this operation, which is still successfully combatting piracy off the coast of Somalia almost a decade later. A second such intervention was launched in 2015 to tackle migration problems in the southern Mediterranean (EUNAVFOR Med), working under the name Operation SOPHIA.

Most of the CSDP missions deployed so far are mandated to support Security Sector Reforms (SSR) in host-states. One of the core principles of CSDP support to SSR is local ownership. The EU Council defines ownership as “the appropriation by the local authorities of the commonly agreed objectives and principles”. [21]. Despite EU's strong rhetorical attachment to the local ownership principle, research shows that CSDP missions continue to be an externally driven, top-down and supply-driven endeavour, resulting often in the low degree of local participation. [22]

Structure

The following permanent political and military bodies were established after the approval of the European Council.

- Political and Security Committee or PSC

- European Union Military Committee or EUMC

- European Union Military Staff or EUMS

- Committee for Civilian Aspects of Crisis Management or CIVCOM

- Politico-Military Group or PMG

- Crisis Management and Planning Directorate or CMPD

- Civilian Planning and Conduct Capability or CPCC

The following agencies has been established after the incorporation of the Western European Union within the EU

- European Union Satellite Centre or SatCen

- European Defence Agency or EDA

- European Union Institute for Security Studies or ISS

- European Security and Defence College or ESDC

The CSDP is furthermore strongly facilitated by the European External Action Service.

From 1 January 2007, the EU Operations Centre began work in Brussels. It can command a limited size force of about 2000 troops (e.g. a battlegroup).

In addition to the EU centre, 5 national operational headquarters have been made available for use by the Union; Mont Valérien in Paris, Northwood in London, Potsdam, Centocelle in Rome and Larissa. For example, Operation Artemis used Mont Valérien as its OHQ and EUFOR's DR Congo operation uses Potsdam. The EU can also use NATO capabilities.[23]

With effect from 1 January 2007, the EU will have a third option for commanding, from Brussels, missions and operations of limited size (that is, like that of a battlegroup: some 2,000 troops). On that date, the new EU Operations Centre (EUOC) within the EU Military Staff (EUMS) will be ready for action. Using some EUMS core staff, as well as some extra “double-hatted” EUMS officers and so-called “augmentees” from the Member States, the EU will have an increased capacity to respond to crisis management situations. So far, the EU has had two options as to how to run a military operation at the Operation Headquarters (OHQ) level. One option is, in a so-called “autonomous” operation, to make use of facilities provided by any of the five Operation Headquarters (OHQs) currently available in European Member States. A second option is, through recourse to NATO capabilities and common assets (under the so-called “Berlin plus” arrangements), to make use of command and control options such as Operation Headquarters located at Supreme Headquarters, Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE) in Mons, Belgium and D-SACEUR as the Operation Commander. This is the option used in the conduct of Operation ALTHEA, where EUFOR BiH operates in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[23]

See also

- European External Action Service

- Military of the European Union

- Eurocorps

- European Union Police Mission (disambiguation)

- European defence procurement

- European Gendarmerie Force

- OCCAR

- European Union battle groups

- Helsinki Headline Goal

- Berlin Plus agreement

- Franco-British Defence and Security Cooperation Treaty and Downing Street Declaration

- Edinburgh Agreement – Denmark

References

- ^ EUROPA - Glossary - Petersberg tasks

- ^ NATO Ministerial Meetings Berlin - 3-4 June 1996

- ^ Meltem Mueftueler-Bac & Damla Cihangir, "The Transatlantic Relationship and the Future Global Governance," European Integration and Transatlantic Relations, (2012), p 12, www.iai.it/pdf/Transworld/TW_WP_05.pdf

- ^ CDI Military Reform Project - European Union - Centre for Defence Information Archived March 9, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The full report can be found here Archived 2006-02-15 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ consilium.europa.eu: "Report on the Implementation of the European Security Strategy - Providing Security in a Changing World" 11 Dec 2008

- ^ Statement of the Presidency of the Permanent Council of the WEU on behalf of the High Contracting Parties to the Modified Brussels Treaty – Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, The Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom, Western European Union 31 March 2010

- ^ a b c d "Article 42(6), Article 43(1), Article 46, Protocol 10 of the amended Treaty on European Union" (PDF).

- ^ Banila, Nicoleta (2017-10-17). "Romania to join EU's defence initiative PESCO". SeeNews. Archived from the original on 2017-10-18. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "EU defence ministers: defence cooperation needs to be brought to a new level". Estonian Presidency of the Council of the European Union. 2017-09-07. Archived from the original on 2017-10-18. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Permanent Structured Cooperation on defence could be launched by end 2017". European External Action Service. 2017-09-08. Archived from the original on 2017-09-12. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Czech government to join PESCO defence project". Prague Daily Monitor. 2017-10-12. Archived from the original on 2017-10-12. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) - Council Decision - preparation for the adoption". Council of the European Union. 2017-12-08. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- ^ "PESCO: EU paves way to defense union". Deutsche Welle. 2017-11-13. Archived from the original on 2017-11-18. Retrieved 2017-11-16.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Erlanger, Steven (2017-11-13). "E.U. Moves Closer to a Joint Military Force". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2017-11-13. Retrieved 2017-11-13.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Malta among three countries opting out of EU's new defence agreement". Times of Malta. 2017-12-11. Archived from the original on 2017-12-12. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Twenty-five EU states sign PESCO defense pact". Deutsche Welle. 2017-12-11. Archived from the original on 2017-12-12. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- ^ Christopher S. Chivvis, "Birthing Athena. The Uncertain Future of ESDP" Archived 2008-06-27 at the Wayback Machine, Focus stratégique, Paris, Ifri, March 2008.

- ^ "EUFOR Tchad/RCA" consilium.europa.eu

- ^ Benjamin Pohl (2013) The logic underpinning EU crisis management operations Archived 2014-12-14 at the Wayback Machine, European Security, 22(3): 307-325, DOI:10.1080/09662839.2012.726220, p. 311.

- ^ http://www.ifp-ew.eu/resources/EU_Concept_for_ESDP_support_to_Security_Sector_Reform.pdf

- ^ Filip Ejdus, ‘Here is your mission, now own it!’ the rhetoric and practice of local ownership in EU interventions’, European Security, published online 6 June 2017 http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09662839.2017.1333495

- ^ a b EU Operations Centre consilium.europa.eu. Archived at Wayback Machine on 30 Mar 2008.

Further reading

- Book - What ambitions for European defence in 2020?, European Union Institute for Security Studies

- Book - European Security and Defence Policy: The first 10 years (1999–2009), European Union Institute for Security Studies

- "Guide to the ESDP" nov.2008 edition Exhaustive guide on ESDP's missions, institutions and operations, written and edited by the Permanent representation of France to the European Union.

- Dijkstra, Hylke (2013). Policy-Making in EU Security and Defense: An Institutional Perspective. European Administrative Governance Series (Hardback 240pp ed.). Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke. ISBN 978-1-137-35786-1.

- Nugent, Neill (2006). The Government and Politics of the European Union. The European Union Series (Paperback 630pp ed.). Palgrave Macmillan, New York. ISBN 9780230000025.

- Howorth, Joylon (2007). Security and Defence Policy in the European Union. The European Union Series (Paperback 315pp ed.). Palgrave Macmillan, New York. ISBN 978-0-333-63912-2.

- PhD Thesis on Civilian ESDP - EU Civilian crisis management (University of Geneva, 2008, 441 p. in French)

- Hayes, Ben (2009). NeoConOpticon: The EU Security-Industrial Complex (Paperback, 84 pp ed.). Transnational Institute/Statewatch. ISSN 1756-851X.

- Giovanni Arcudi & Michael E. Smith (2013). The European Gendarmerie Force: a solution in search of problems?, European Security, 22(1): 1–20, DOI:10.1080/09662839.2012.747511

- Teresa Eder (2014). Welche Befugnisse hat die Europäische Gendarmerietruppe?, Der Standard, 5 Februar 2014.

- Alexander Mattelaer (2008). The Strategic Planning of EU Military Operations - The Case of EUFOR Tchad/RCA, IES Working Paper 5/2008.

- Benjamin Pohl (2013). The logic underpinning EU crisis management operations, European Security, 22(3): 307-325, DOI:10.1080/09662839.2012.726220

- "The Russo-Georgian War and Beyond: towards a European Great Power Concert", Danish Institute of International Studies.

- U.S Army Strategic Studies Institute (SSI), Operation EUFOR TCHAD/RCA and the EU's Common Security and Defense Policy., U.S. Army War College, October 2010

- Mai'a K. Davis Cross "Security Integration in Europe: How Knowledge-based Networks are Transforming the European Union." University of Michigan Press, 2011.