Joseph McCarthy: Difference between revisions

revert, not a forum to bash or praise him |

just the facts--fully sourced; impossible to understand politics without knowing them |

||

| Line 196: | Line 196: | ||

| id = ISBN 0-684-83625-4 }}</ref> |

| id = ISBN 0-684-83625-4 }}</ref> |

||

It was the Truman Administration's State Department that McCarthy accused of harboring 205 (or 57 or 81) "known Communists," and Truman's [[Secretary of Defense]] [[George Marshall]] who was the target of some of McCarthy's most colorful and memorable rhetoric. Marshall was also Truman's former [[United States Secretary of State|Secretary of State]] and had been [[Chief of Staff of the United States Army|Army Chief of Staff]] during World War II. Marshall was a highly respected statesman and general, best remembered today as the architect of the [[Marshall Plan]] for post-war reconstruction of Europe, for which he was awarded the [[Nobel Peace Prize]] in 1953. McCarthy authored a book titled ''America's retreat from victory; the story of George Catlett Marshall'', accused Marshall of treason, of "aid(ing) the Communist drive for world domination," said "if Marshall was merely stupid, the laws of probability would dictate that part of his decisions would serve America's interests," and most famously, accused him of being part of "a conspiracy so immense and an infamy so black as to dwarf any previous venture in the history of man." |

It was the Truman Administration's State Department that McCarthy accused of harboring 205 (or 57 or 81) "known Communists," and Truman's [[Secretary of Defense]] [[George Marshall]] who was the target of some of McCarthy's most colorful and memorable rhetoric. Marshall was also Truman's former [[United States Secretary of State|Secretary of State]] and had been [[Chief of Staff of the United States Army|Army Chief of Staff]] during World War II. Marshall was a highly respected statesman and general, best remembered today as the architect of the [[Marshall Plan]] for post-war reconstruction of Europe, for which he was awarded the [[Nobel Peace Prize]] in 1953. However with over 33,000 Americans dead in Korea and 100,000 wounded.[http://siadapp.dior.whs.mil/personnel/CASUALTY/korea.pdf#search=%22deaths%20korean%20war%22]] with nothing to show for it, Marshall could not escape the blame. McCarthy authored a book titled ''America's retreat from victory; the story of George Catlett Marshall'', accused Marshall of treason, of "aid(ing) the Communist drive for world domination," said "if Marshall was merely stupid, the laws of probability would dictate that part of his decisions would serve America's interests," and most famously, accused him of being part of "a conspiracy so immense and an infamy so black as to dwarf any previous venture in the history of man." |

||

After Truman dismissed General [[Douglas MacArthur]] during the [[Korean War]], McCarthy, using another phrase that would become famous, charged that Truman and his advisors must have planned the dismissal during a "midnight Bourbon-and-Benedictine session." |

After Truman dismissed General [[Douglas MacArthur]] during the [[Korean War]], McCarthy, using another phrase that would become famous, charged that Truman and his advisors must have planned the dismissal during a "midnight Bourbon-and-Benedictine session." |

||

Revision as of 02:13, 21 September 2006

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was a Republican Senator from the U.S. state of Wisconsin between 1947 and 1957, and one of the first Irish Catholics to become prominent in the Republican party.

During his ten years in the Senate, McCarthy gained notoriety for making "freewheeling"[1] accusations of membership in the Communist party or of communist sympathies. These accusations were largely directed towards people in the U.S. government, particularly employees of the State Department, but included many others as well.

During this period, people at every level of society were suspected of being Soviet spies or Communist sympathizers and were the subjects of investigations and questioning regarding their beliefs, affiliations and statements. These inquiries were conducted by a variety of federal and local government committees as well as by private sector "loyalty review" agencies. Joseph McCarthy became the most visible public face of this era of intense anti-Communism, and as a result, the term McCarthyism was coined to describe both the historical period (roughly 1950-1956) and the practices that came to be identified with McCarthy. The American Heritage Dictionary defines "McCarthyism" as "the practice of publicizing accusations of political disloyalty or subversion with insufficient regard to evidence" and "the use of unfair investigatory or accusatory methods in order to suppress opposition."[2]

Early life and career

McCarthy was born on a farm in the town of Grand Chute, Wisconsin. McCarthy's mother, Bridget Tierney, was from County Tipperary, Ireland. His father, Tim McCarthy, was American; the son of an Irish father and a German mother. McCarthy dropped out of junior high school to help his parents manage their farm and later returned to school and earned his diploma in one year. McCarthy worked his way through college, from 1930 to 1935, studying engineering and law, earning a law degree at Marquette University in Milwaukee. He was admitted to the Bar Association in 1935. While working in a law firm in Shawano, Wisconsin, he launched what was ultimately an unsuccessful campaign to become District Attorney as a Democrat in 1936. However, in 1939, McCarthy's luck was better: he successfully vied for the elected post of the non-partisan 10th District circuit judge, becoming the youngest judge in Wisconsin's history.

In 1942, shortly after the U.S. entered World War II, McCarthy enlisted in the United States Marine Corps, despite the fact that his judicial office had exempted him from compulsory service. His position as a judge qualified him for an automatic commission as a second lieutenant, and he would leave the Marines with the rank of captain. He served as an intelligence briefing officer for a dive bomber squadron in the Solomon Islands and Bougainville. McCarthy reportedly chose the Marines with the hope that being a veteran of this branch of the military would serve him best in his future political career.[3]

It is a matter of record that McCarthy (like many politicians who are also veterans) exaggerated his war record. He claimed to have enlisted as a "buck private," though due to his automatic commission he entered basic training as an officer. He flew 12 combat missions as a gunner-observer, but later claimed 32 missions in order to qualify for a Distinguished Flying Cross, which he received in 1952. McCarthy publicized a letter of commendation signed by his commanding officer and countersigned by Admiral Chester Nimitz, but it was revealed that McCarthy had written this letter himself, in his capacity as intelligence officer. A "war wound" that McCarthy made the subject of varying stories involving airplane crashes or antiaircraft fire was in fact received aboard ship during an initiation ceremony for sailors who cross the equator for the first time.[3][4]

McCarthy campaigned for the Republican Senate nomination in Wisconsin while still on active duty in 1944 but was defeated for the GOP nomination by Alexander Wiley, the incumbent. After resigning his commission in April 1945--five months before the end of the Pacific war in September 1945, and being re-elected unopposed to his circuit court position--he began a much more systematic campaign for the 1946 Republican Senate primary nomination, again challenging an incumbent, four-term senator and United States Progressive Party icon, Robert M. La Follette, Jr.

In his campaign, McCarthy attacked La Follette for not enlisting during the war, although La Follette had been 46 when Pearl Harbor was bombed. McCarthy also claimed La Follette had made huge profits from his investments while he, McCarthy, had been away fighting for his country. The suggestion that La Follette had been guilty of war profiteering was deeply damaging, and McCarthy won the primary nomination 207,935 votes to 202,557. It was during this campaign that McCarthy started publicizing the nickname "Tailgunner Joe", using the slogan "Congress needs a tailgunner". Arnold Beichman later reported that McCarthy "was elected to his first term in the Senate with support from the Communist-controlled United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers, CIO," which preferred McCarthy to the anti-communist Robert M. La Follette.[5]

McCarthy enjoyed the support of the state Republican party organization, and he won the nomination narrowly. He won in the general election against Democrat opponent Howard J. McMurray by a 2 to 1 margin, and thus joined Senator Wiley (whom McCarthy had challenged two years earlier) in the Senate.

Senator

McCarthy's first three years in the Senate were unremarkable. McCarthy was a popular speaker, invited by many different organizations, covering a wide range of topics. His colleagues and aides considered him to be friendly and likeable. He was active in labor-management issues, with a reputation as a moderate Republican. He fought against continuation of wartime price controls, especially on sugar. He supported the Taft-Hartley Act over Truman's veto, angering labor unions in Wisconsin but solidifying his business base.[6]. Following the lead of Senator Robert Taft, McCarthy lobbied for the commutation of death sentences handed to a group of Waffen-SS soldiers convicted of war crimes for their involvement in the 1944 Malmedy massacre of American prisoners of war. Taft had been critical of the proceedings because of allegations of misconduct during the interrogations that led to the confessions, as well as his objections of Soviet involvement in the trial.[7]

Kennedy family and Irish Catholics

McCarthy became good friends with Joseph P. Kennedy, Sr. in the late 1940s, in part because of their connection as fellow Irish Catholics. He was a frequent guest at the Kennedy home in Hyannis Port, and at one point dated Patricia Kennedy. After McCarthy became nationally prominent Kennedy was a vocal supporter, and helped build McCarthy's popularity among Catholics. Kennedy contributed cash and encouraged his friends to give money. Some historians have argued that in the Senate race of 1952, Joseph Kennedy and McCarthy made a deal that McCarthy would not make campaign speeches for the Republican ticket in Massachusetts, and in return, Congressman John F. Kennedy would not give anti-McCarthy speeches. In 1953 McCarthy hired Robert Kennedy (age 27) as a senior staff member. When the Senate voted to censure McCarthy on December 2, 1954, Senator Kennedy was in the hospital and never indicated then or later how he would vote.[8]

Wheeling speech

McCarthy's national profile rose meteorically after his Lincoln Day speech on February 9, 1950, to the Republican Women's Club of Wheeling, West Virginia.

McCarthy's words in the speech are a matter of some dispute, as they were not reliably recorded at the time. It is generally agreed, however, that he produced a piece of paper which he claimed contained a list of known Communists working for the State Department. McCarthy is usually quoted to have said: "I have here in my hand a list of 205 people that were known to the Secretary of State as being members of the Communist Party, and who, nevertheless, are still working and shaping the policy of the State Department."

There is a great deal of dispute about whether or not McCarthy actually gave the number of people on the list as being "57" or "205". In a later telegram to President Truman, and when entering the speech into the Congressional Record, he used the number 57[9] . The origin of the number 205 can be traced: In later debates on the Senate floor, McCarthy referred to a 1946 letter that then-Secretary of State James Byrnes sent to Congressman Adolph J. Sabath. In that letter, Byrnes said State Department security investigators had resulted in "recommendation against permanent employment" for 285 persons, and that only 79 of these had been removed from their jobs. With some slightly faulty arithmetic on McCarthy's part, this left 205 still on the State Department's payroll. On the Senate floor, McCarthy said that while he did not have the names of the 205 mentioned in the Byrnes letter, he did have the names of 57 who were either members of or loyal to the Communist Party. McCarthy stated he referred to 57 "known Communists"; the number 205 was referring to the number of people employed by the State Department who, for various reasons, had been recommended for removal by the State Department's security investigators.[9] The exact number stated by McCarthy would later become a matter of some importance when the matter was brought before the Tydings Committee.

At the time of McCarthy's speech, Communism was a growing concern in the United States. This concern was worsened by the actions of the Soviet Union in Eastern Europe, the fall of China to the Maoists, the Soviets' development of the atomic bomb the year before and by the recent conviction of Alger Hiss and the confession of Soviet spy Klaus Fuchs. With this background and due to the sensational nature of McCarthy's charge against the State Department, the Wheeling speech attracted a flood of press interest in McCarthy.

Tydings Committee

The Tydings Committee was a subcommittee of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that was set up in February 1950 to conduct "a full and complete study and investigation as to whether persons who are disloyal to the United States are, or have been, employed by the Department of State." The chairman of the subcommittee, Senator Millard Tydings, a Democrat, told McCarthy at the opening of the hearings: "You are in the position of being the man who occasioned this hearing, and so far as I am concerned in this committee you are going to get one of the most complete investigations ever given in the history of this Republic, so far as my abilities will permit."

McCarthy himself was taken aback by the massive media response to the Wheeling speech, and he was accused of continually revising both his charges and his figures. In Salt Lake City, Utah, a few days later, he cited a figure of 57, and in the Senate on February 20, he claimed 81. During a marathon 6-hour speech, McCarthy fought Democratic attempts to disclose the actual names of these people. Four times during McCarthy's February 20 speech, Democratic Senator Scott W. Lucas demanded McCarthy make the 81 names public, but McCarthy refused to do so, saying: "If I were to give all the names involved, it might leave a wrong impression. If we should label one man a Communist when he is not a Communist, I think it would be too bad." In fact, McCarthy had no actual names; his evidence for this particular list came from summaries of State Department loyalty review files, from which the names had been removed.[10] Instead he just had case numbers. Eventually McCarthy moved on from his original list of unnamed individuals and used the hearings to make charges against ten others for whom he had names: Dorothy Kenyon, Esther and Stephen Brunauer, Haldore Hanson, Gustavo Duran, Owen Lattimore, Harlow Shapley, Frederick Schuman, John S. Service and Philip Jessup. Some of these no longer, or never had, worked for the State Department, and all had previously been the subject of various charges of varying worth and validity. Owen Lattimore became a particular focus of McCarthy's, who at one point described him as a "top Russian spy." Throughout the hearings, McCarthy had colorful rhetoric, but no substantial evidence, to support his accusations.

From its beginning, the Tydings Committee was marked by partisan infighting. Its final report, written by the Democratic majority, concluded that the individuals on McCarthy's list were neither Communists nor pro-communist, and said the State Department had an effective security program. Tydings labeled McCarthy's charges a "fraud and a hoax," and said that the result of McCarthy's actions was to "confuse and divide the American people[...] to a degree far beyond the hopes of the Communists themselves." Republicans responded in kind, with William Jenner stating that Tydings was guilty of "the most brazen whitewash of treasonable conspiracy in our history." The full Senate voted three times on whether to accept the report, and each time the voting was precisely divided along party lines.[11]

Continuing Anti-Communism

From 1950 onward, McCarthy continued to press his accusations that the government was failing to deal with Communism within its ranks, which increased his approval rating and gained him a powerful national following. During a speech in Milwaukee in 1952, McCarthy dated the public phase of his fight against Communists to the May 22, 1949, death of former Secretary of Defense James Forrestal, apparently by suicide. "The Communists hounded Forrestal to his death," McCarthy said. "They killed him just as definitely as if they had thrown him from that 16th-story window in Bethesda Naval Hospital."

McCarthy has been accused of attempting to discredit his critics and political opponents by accusing them of being Communists or communist-sympathizers. In the 1950 Maryland Senate election, McCarthy campaigned for John M. Butler in his race against four-term incumbent Millard Tydings, with whom McCarthy had been in conflict during the Tydings Committee hearings. In speeches supporting Butler, McCarthy accused Tydings of "protecting Communists" and "shielding traitors" McCarthy's staff was heavily involved in the campaign, and collaborated in the production of a campaign tabloid that contained a composite photograph doctored to make it appear that Tydings was in intimate conversation with Communist leader Earl Browder. A Senate subcommittee later investigated this election and referred to it as "a despicable, back-street type of campaign."[12]

McCarthy was physically violent toward his critics on at least one occasion. He assaulted journalist Drew Pearson in the cloakroom of a Washington club, reportedly kneeing him in the groin. McCarthy, who admitted the assault, claimed he merely "slapped" Pearson.[13]

McCarthy and Truman

There was considerable enmity between McCarthy and President Truman throughout the time they were both in office. McCarthy sought to characterize President Truman and the Democratic party as soft on or even in league with the Communists, referring to "twenty years of treason" on the part of the Democrats. Truman, in turn, once referred to McCarthy as "the best asset the Kremlin has," and said his attempts to "sabotage the foreign policy of the United States" in a cold war was comparable to shooting American soldiers in the back in a hot war.[14]

It was the Truman Administration's State Department that McCarthy accused of harboring 205 (or 57 or 81) "known Communists," and Truman's Secretary of Defense George Marshall who was the target of some of McCarthy's most colorful and memorable rhetoric. Marshall was also Truman's former Secretary of State and had been Army Chief of Staff during World War II. Marshall was a highly respected statesman and general, best remembered today as the architect of the Marshall Plan for post-war reconstruction of Europe, for which he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1953. However with over 33,000 Americans dead in Korea and 100,000 wounded.[1]] with nothing to show for it, Marshall could not escape the blame. McCarthy authored a book titled America's retreat from victory; the story of George Catlett Marshall, accused Marshall of treason, of "aid(ing) the Communist drive for world domination," said "if Marshall was merely stupid, the laws of probability would dictate that part of his decisions would serve America's interests," and most famously, accused him of being part of "a conspiracy so immense and an infamy so black as to dwarf any previous venture in the history of man."

After Truman dismissed General Douglas MacArthur during the Korean War, McCarthy, using another phrase that would become famous, charged that Truman and his advisors must have planned the dismissal during a "midnight Bourbon-and-Benedictine session."

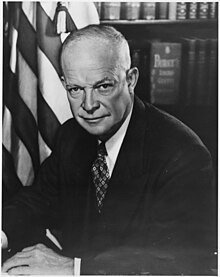

McCarthy and Eisenhower

With his victory in the 1952 presidential race, Dwight Eisenhower became the first Republican president in 20 years. The Republican party also held a majority in the House of Representatives and the Senate. Those who expected that party loyalty would cause McCarthy to tone down his accusations of Communists being harbored within the government were soon disappointed. Eisenhower had never been an admirer of McCarthy, and their relationship became more hostile once Eisenhower was in office.

During the 1952 campaign, Eisenhower's campaign schedule included a tour through Wisconsin with McCarthy. In a speech he delivered in Green Bay, Eisenhower declared that while he agreed with McCarthy's goals, he disagreed with his methods. Eisenhower also included a strong defense of George Marshall in draft versions of his speech, in direct contradiction of McCarthy's frequent attacks on Marshall. However, under the advice of conservative colleagues who were fearful that that Eisenhower could lose Wisconsin if he alienated McCarthy supporters, he cut these parts from later versions of his speech.[15][16] Eisenhower was widely criticized during his campaign for "selling out" to pressure and giving up his personal convictions because of party pressures. After being elected president, he made it clear to those close to him that he did not approve of McCarthy and he worked actively to squelch his power and influence. But he never directly confronted McCarthy or criticized him by name in any speech, thus perhaps prolonging McCarthy's power by showing that even the President was afraid to criticize him directly.

IIn 1952, using rumors collected by Drew Pearson, Nevada publisher Hank Greenspun wrote that both McCarthy and Roy Cohn were homosexuals.Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page).

In a November 1953 speech that was carried on national television, McCarthy began by praising the Eisenhower Administration for removing "1,456 Truman holdovers who were [...] gotten rid of because of Communist connections and activities or perversion." He then went on to complain that John P. Davies was still "on the payroll after eleven months of the Eisenhower Administration," (Davies had been fired three weeks earlier) and repeated an unsubstantiated accusation that Davies had tried to "put Communists and espionage agents in key spots in the Central Intelligence Agency." In the same speech he criticized Eisenhower for not doing enough to secure the release of missing American pilots shot down over China during the Korean War.[17]

By the end of 1953, McCarthy had altered the "twenty years of treason" catch-phrase he had coined for the preceding Democratic administrations and began referring to "twenty one years of treason." to include Eisenhower's first year in office.

As McCarthy became increasingly combative towards the Eisenhower Administration, Eisenhower faced repeated calls that he confront McCarthy directly. Eisenhower refused, saying privately "nothing would please him [McCarthy] more than to get the publicity that would be generated by a public repudiation by the President."[18] On several occasions Eisenhower is reported to have said of McCarthy that he didn't want to "get down in the gutter with that guy."[19]

The Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations

With the beginning of his second term as Senator in 1953, McCarthy was made chairman of the Senate Committee on Government Operations. According to some reports, Republican leaders were growing wary of McCarthy's methods and gave him this relatively mundane panel rather than the Internal Security Subcommittee--the committee normally involved with investigating Communists--thus putting McCarthy "where he can't do any harm," in the words of Senate Majority Leader Robert Taft.[20] However, the Committee on Government Operations included the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, and the mandate of this subcommittee was sufficiently flexible to allow McCarthy to use it for his own investigations of Communists in the government. McCarthy appointed Roy Cohn as chief counsel and Robert Kennedy as an assistant counsel to the subcommittee.

The subcommittee first investigated allegations of Communist influence in the Voice of America (VOA), at that time a part of the State Department's International Information Agency. Many VOA personnel were questioned in front of television cameras and a packed press gallery, with McCarthy lacing his questions with innuendo and false accusations.[21] A few VOA employees alleged Communist influence on the content of broadcasts, but none of the charges were substantiated. Morale at VOA was badly damaged, with one of its engineers even committing suicide. Ed Kretzman, a policy advisor for the service, would later comment that it was VOA's "darkest hour when Senator McCarthy and his chief hatchet man, Roy Cohn, almost succeeded in muffling it."[22]

The subcommittee then turned to the overseas library program of the International Information Agency. Cohn toured Europe examining the card catalogs of the State Department libraries looking for works by authors he deemed inappropriate. McCarthy then recited the list of supposedly pro-communist authors before his subcommittee and the press. The State Department bowed to McCarthy and ordered its overseas librarians to remove from their shelves "material by any controversial persons, Communists, fellow travelers, etc." Some libraries actually burned the newly-forbidden books.[23] Shortly after this, in one of his carefully oblique public criticisms of McCarthy, President Eisenhower urged Americans: "Don't join the book burners. […] Don't be afraid to go in your library and read every book."[24]

Soon after receiving the chair to the Subcommittee on Investigations, McCarthy appointed Joseph Brown Matthews (generally known as J. B. Matthews) as staff director of the subcommittee. A fervent anti-communist, Matthews had formerly been staff director for the House Committee on Un-American Activities. Matthews combined his anti-Communism with a powerful dislike of the Protestant religion, and had recently written an article called "Reds and Our Churches"[25] which opened with the sentence "The largest single group supporting the Communist apparatus in the United States is composed of Protestant Clergymen.". On learning of this, a group of Senators denounced this "shocking and unwarranted attack against the American clergy" and demanded of McCarthy that he fire Matthews. McCarthy at first refused, but as the controversy mounted and the majority of his own subcommittee joined the call for Matthew's ouster, McCarthy finally yielded and accepted Matthew's resignation. For some McCarthy opponents, this was a signal defeat of the Senator, showing he was less invincible than he formerly seemed.[26]

Investigating the army

In the fall of 1953, McCarthy's committee began its ill-fated inquiry into the United States Army. This began with McCarthy opening an investigation into the Army Signal Corps laboratory at Fort Monmouth. McCarthy garnered some headlines with stories of a dangerous spy ring among the army researchers, but after weeks of hearings, nothing came of his investigations.[27]

At about this time, Senator McCarthy was alerted to the story of Irving Peress, a New York dentist who had been drafted into the army in 1952 and promoted to major in November of 1953 through the provisions of the Doctor Draft Law. Shortly thereafter it came to the attention of the military bureaucracy that Peress, who was a member of the left-wing American Labor Party, had declined to answer questions about his political affiliations on a loyalty review form. Peress' superiors were therefore ordered to discharge him from the army within ninety days. McCarthy subpoenaed Peress to appear before his subcommittee on January 30, 1954. Peress refused to answer McCarthy's questions, citing his rights under the Fifth Amendment. McCarthy responded by sending a message to Secretary of the Army Robert Stevens demanding that Peress be court-martialed. On that same day, Peress asked for his pending discharge to be effected immediately, and the next day Brigadier General Ralph W. Zwicker, his commanding officer at Camp Kilmer in New Jersey, gave him an honorable separation from the army.

McCarthy summoned General Zwicker to his subcommittee on February 18. Zwicker, on advice from army counsel, refused to answer some of McCarthy's questions and reportedly changed his story three times when asked if he had known at the time he signed the discharge that Peress had refused to answer questions before the McCarthy subcommittee. McCarthy compared Zwicker's intelligence to that of a "five-year-old child," and said he was "not fit to wear the uniform of a General."

This abuse of Zwicker, a battlefield hero of World War II, caused considerable outrage among the military, newspapers, the President and Senators of both parties.[28] Army Secretary Stevens ordered Zwicker not to return to McCarthy's hearing for further questioning. Hoping to mend the increasingly hostile relations between McCarthy and the army, a group of Republicans met with Secretary Stevens and convinced him to sign a "memorandum of understanding" in which he capitulated to most of McCarthy's demands. McCarthy later told a reporter that Stevens "could not have given in more abjectly if he had got down on his knees."[29] Reaction to this agreement was widely negative. Secretary Stevens was ridiculed by Pentagon officers,[30] and the Times of London wrote: "Senator McCarthy achieved today what General Burgoyne and General Cornwallis never achieved--the surrender of the American Army."[31]

A few months later, the army, with advice and support from the Eisenhower Administration, would launch a counterattack against McCarthy. It would do this not by directly challenging and criticizing McCarthy's behavior toward army personnel, but by bringing charges against him on an unrelated issue.

The army-McCarthy hearings

Early in 1954, the U.S. Army accused McCarthy and his chief counsel, Roy Cohn, of pressuring the army to give favorable treatment to another former aide and friend of Cohn's, G. David Schine. McCarthy claimed that the accusation was made in bad faith, in retaliation for his questioning of Zwicker the previous year. The Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, usually chaired by McCarthy himself, was given the task of adjudicating these conflicting charges. Republican Senator Karl Mundt was appointed to chair the committee, and the Army-McCarthy hearings convened on April 22, 1954.

The hearings lasted for 36 days and were were broadcast on live television, with an estimated 20 million viewers. After hearing 32 witnesses and two million words of testimony, the committee concluded that McCarthy himself had not exercised any improper influence on behalf of David Schine, but that Roy Cohn had engaged in "unduly persistent or aggressive efforts". The committee also concluded that Army Secretary Robert Stevens and army Counsel John Adams "made efforts to terminate or influence the investigation and hearings at Fort Monmouth," and that Adams "made vigorous and diligent efforts" to block subpoenas for members of the army Loyalty and Screening Board "by means of personal appeal to certain members of the [McCarthy] committee."

Far more important to McCarthy than the committee's inconclusive final report was the effect the extensive exposure had on his popularity. Many in the audience saw him as bullying, reckless and dishonest. Late in the hearings, Senator Stuart Symington made an angry but prophetic remark to McCarthy: "The American people have had a look at you for six weeks," he said. "You are not fooling anyone."[32] In Gallup polls of January, 1954, 50% of those polled had a positive opinion of McCarthy. In June, that number had fallen to 34%. In the same polls, those with a negative opinion of McCarthy increased from 29% to 45%.[33] An increasing number of Republicans and conservatives were coming to see McCarthy as a liability to the party and to anti-communism. Congressman George H. Bender noted "There is a growing impatience with the Republican Party. McCarthyism has become a synonym for witch-hunting, star chamber methods and the denial of[...] civil liberties." Frederick Woltman, a reporter with a long-standing reputation as a staunch anti-communist, wrote in New York World-Telegram that McCarthy "has become a major liability to the cause of anti-communism."[34]

The most famous incident in the hearings was an exchange between McCarthy and the army's attorney general Joseph Welch. On June 9, the 30th day of the hearings, Welch challenged Roy Cohn to give the Attorney General McCarthy's list of 130 Communists or subversives in defense plants "before the sun goes down." McCarthy stepped in and said that if Welch was so concerned about persons aiding the Communist Party, he should check on a man in his Boston law office named Fred Fisher, who had once belonged to the National Lawyers Guild, which Attorney General Brownell had called "the legal mouthpiece of the Communist Party." In an impassioned defense of Fisher that some have suggested he had prepared in advance,[35] Welch responded, "Until this moment, Senator, I think I never gauged your cruelty or your recklessness[...]" When McCarthy resumed his attack, Welch interrupted him: "Let us not assassinate this lad further, Senator. You've done enough. Have you no sense of decency, sir? At long last, have you left no sense of decency?" He then left the room to loud applause from the spectators, and a recess was called.

Edward Murrow, "See It Now"

One of the most prominent attacks on McCarthy's methods was an episode of the TV documentary series See It Now, hosted by journalist Edward R. Murrow, which was broadcast on March 9, 1954.

The March 1954 show was preceded by one on a related topic, about the dismissal of Milo Radulovich, a former reserve Air Force lieutenant who was accused of associating with Communists in 1953. The program was aired on October 20, 1953 and advanced opposition of the American public against McCarthy.

The March 9, 1954 show consisted largely of clips of McCarthy speaking. In these clips, McCarthy

- accuses the Democratic party of being "in charge of twenty years of treason"

- makes a similar accusation against the Republican administration of Eisenhower

- incorrectly states that the American Civil Liberties Union is listed by the Attorney General as a front organization for the Communist party

- accuses Secretary Stevens of telling "two army officers that they had to take part in the cover-up of those who promoted and coddled Communists."

- badgers a witness, accused of helping the Communist cause by curtailing some broadcasts to Israel, over an irrelevant and unsuccessful book written 21 years earlier

- berates other witnesses, including General Zwicker[36]

The Murrow report, together with the televised army-McCarthy hearings of the same year, were the major causes of a nationwide popular opinion backlash against McCarthy, in part because for the first time his statements were being publicly challenged by news figures. To counter the negative publicity, McCarthy appeared on See It Now on April 6, 1954 and made a number of charges against Murrow. This response did not go over well with viewers, and the result was a further decline in his popularity. President Eisenhower, now free of McCarthy's political intimidation, referred to "McCarthywasm" in conversation with a reporter.

Censure and the Watkins Committee

Several members of the U.S. Senate opposed McCarthy well before 1953. One example is U.S. Senator Margaret Chase Smith, a Maine Republican who delivered her "Declaration of Conscience" on June 1, 1950, calling for an end to the use of smear tactics without mentioning McCarthy or anyone else by name. Six other Republican Senators, Wayne Morse, Irving M. Ives, Charles W. Tobey, Edward John Thye, George Aiken and Robert C. Hendrickson joined her in condemning McCarthy's tactics. McCarthy referred to Smith and her fellow Senators as "Snow White and the 6 dwarves."

Vermont Republican Senator Ralph E. Flanders had also condemned McCarthy on the floor of the Senate, comparing McCarthy to Hitler, accused him of spreading "division and confusion" and said "Were the Junior Senator from Wisconsin in the pay of the Communists he could not have done a better job for them."[37] In June of 1954, Flanders introduced a resolution to have McCarthy removed as chair of his committees. Although there were many in the Senate who believed that some sort of disciplinary action against McCarthy was called for, there was no clear majority supporting this resolution. Some of the resistance was due to concern about usurping the Senate's rules regarding committee chairs and seniority. Flanders next introduced a resolution to censure McCarthy. The resolution was initially written without any reference to particular actions or misdeeds on McCarthy's part. As Flanders put it, "It was not his breaches of etiquette, or of rules or sometimes even of laws which is so disturbing," but rather his overall pattern of behavior. Ultimately a "bill of particulars" listing 46 charges was added to the censure resolution. A special committee, chaired by Senator Arthur V. Watkins, was appointed to study and evaluate the resolution. This committee opened hearings on August 31, 1954.[38]

After two months of hearings and deliberations, the Watkins Committee recommended that McCarthy be censured on two of the 46 counts: his contempt of the Subcommittee on Rules and Administration, which had called him to testify in 1951 and 1952, and his abuse of General Zwicker in 1954. The Zwicker count was dropped by the full Senate on the grounds that McCarthy's conduct was arguably "induced" by Zwicker's own behavior. In place of this count, a new one was drafted regarding McCarthy's statements about the Watkins Committee itself.[39]

Thus the two counts that the Senate ultimately voted on were:

- That McCarthy had "failed to cooperate with the Subcommittee on Rules and Administration," and "repeatedly abused the members who were trying to carry out assigned duties..."

- That McCarthy had charged "three members of the [Watkins] Select Committee with 'deliberate deception' and 'fraud'... that the special Senate session... was a 'lynch party'," and had characterized the committee "as the 'unwitting handmaiden,' 'involuntary agent' and 'attorneys in fact' of the Communist Party," and had "acted contrary to senatorial ethics and tended to bring the Senate into dishonor and disrepute, to obstruct the constitutional processes of the Senate, and to impair its dignity."[40]

On December 2, 1954, the Senate voted to "condemn" Senator Joseph McCarthy on both counts by a vote of 67 to 22, with the Democrats unanimously in favor of condemnation and the Republicans split evenly. As soon as the vote was taken, Senator H. Styles Bridges, a McCarthy supporter, argued that because the word "condemn" rather than "censure" was used in the final draft, the resolution was "not a censure resolution." The word "censure" was then removed from the title of the resolution, although it is still generally regarded and referred to as a censure of McCarthy.[41] The Senate had invoked censure against one of its members only three times before in the nation's history.

McCarthy's final years

After his censure, McCarthy continued in his senatorial duties for another two and a half years, but his career as a major public figure was unmistakably over. His colleagues in the Senate avoided him; his speeches on the Senate floor were delivered to a near-empty chamber or were received with conspicuous displays of inattention.[42] The press that had once recorded his every public statement now ignored him, and outside speaking engagements dwindled almost to nothing. Still, McCarthy continued to rail against Communism. He warned against attendance at summit conferences with "the Reds", saying that "you cannot offer friendship to tyrants and murderers … without advancing the cause of tyranny and murder." He declared that "coexistence with Communists is neither possible nor honorable nor desirable. Our long-term objective must be the eradication of Communism from the face of the earth."

McCarthy's biographers are agreed that he was a changed man after the censure; declining both physically and emotionally, he became a "pale ghost of his former self" in the words of Fred J. Cook.[43] It was reported that McCarthy suffered from cirrhosis of the liver and was frequently hospitalized for alcoholism. Numerous eyewitnesses, including Senate aide George Reedy and journalist Tom Wicker, have reported finding him alarmingly drunk in the Senate. Journalist Richard Rovere (1959) wrote:

- He had always been a heavy drinker, and there were times in those seasons of discontent when he drank more than ever. But he was not always drunk. He went on the wagon (for him this meant beer instead of whiskey) for days and weeks at a time. The difficulty toward the end was that he couldn't hold the stuff. He went to pieces on his second or third drink. And he did not snap back quickly.

He died in Bethesda Naval Hospital on May 2, 1957, at the age of 48. The cause of his death was variously reported as acute hepatitis and cirrhosis. He was given a state funeral attended by 70 Senators, and St. Matthew's Cathedral performed a Solemn Pontifical Requiem before over a hundred priests and 2,000 others. Thousands of people viewed the body in Washington. He was buried in St. Mary's Parish Cemetery, Appleton, Wisconsin, where more than 30,000 filed through St. Mary's Church to pay their last respects. Three senators—George Malone, William E. Jenner, and Herman Welker—had flown from Washington to Appleton on the plane carrying McCarthy's casket. He was survived by his wife Jean, and their adopted daughter, Tierney.

Continuing controversy

In the view of some modern authors, McCarthy's place in history should be reevaluated. Ann Coulter's book Treason: Liberal Treachery from the Cold War to the War on Terrorism is the best known example of this; Coulter devotes a chapter to her defense of McCarthy, and much of the book to a defense of McCarthyism. She states, for example, "Everything you think you know about McCarthy is a hegemonic lie. Liberals denounced McCarthy because they were afraid of getting caught, so they fought back like animals to hide their own collaboration with a regime as evil as the Nazis."[44] Other authors who have voiced similar opinions include William Norman Grigg of the John Birch Society,[45] and M. Stanton Evans.[46]

Another recent defense of McCarthy was written by William F. Buckley in the form of a laudatory fictionalized biography: The Red Hunter: a Novel Based on the Life of Senator Joe McCarthy.[47]

These authors often claim that new evidence, in the form of Venona decrypted Soviet messages, Soviet espionage data now opened to the West, and newly released transcripts of closed hearings before McCarthy's subcommittee, have vindicated McCarthy, showing that many of his identifications of Communists were correct. It has also been said that Venona and the Soviet archives have revealed that the scale of Soviet espionage activity in the United States during the 40s and 50s was larger than many scholars suspected,[48] [49] and that this too stands as a vindication of McCarthy.

These attempts to "rehabilitate" McCarthy have not received much attention from scholars, though there have been some responses from such authors as Kevin Drum[50] and Johann Hari.[51]

Of the many individuals that figured in McCarthy's investigations or speeches, most were already suspected of being Communists or at least of having leftist politics. There are several cases where Venona or other recent data has confirmed or increased the weight of evidence that a person named by McCarthy was a Soviet agent. However, there are few, if any, cases where McCarthy was responsible for identifying a person, or removing a person from a sensitive government position, where later evidence has increased the likelihood that that person was a Communist or a Soviet agent.[52]

The names that various authors have listed as "correctly identified by McCarthy" include:

|

HUAC

McCarthy is often incorrectly described as part of the House Committee on Un-American Activities (technically, HCUA, but generally known as HUAC). HUAC is best known for the investigation of Alger Hiss, and for its investigation of the Hollywood film industry, which led to the blacklisting of hundreds of actors, writers and directors. HUAC was established in May 1938 as the "Dies Committee" before McCarthy was elected to the Federal office, and, being a House committee, had no connection with McCarthy, who served in the Senate.

McCarthy in popular culture

- In 1953, the popular comic strip Pogo introduced the visiting character "Simple J. Malarkey," a pugnacious and conniving wildcat with an unmistakable physical resemblance to McCarthy.

- "The Investigator" was a 1954 radio play first broadcast by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. The satire links and equates the character representing McCarthy ("The Investigator") to several historical 'witch hunters'.

- In the 1962 film The Manchurian Candidate, the character of Senator John Iselin, a demagogic anti-communist, is strongly patterned after McCarthy, even to the varying numbers of "Communist infiltrators" he purports to have evidence of (in the film the number "57" is decided on, after inspiration by a Heinz ketchup bottle).

- Footage of McCarthy was recently used in the 2005 movie Good Night, and Good Luck about Edward R. Murrow and the fall of McCarthy (see "Edward Murrow, 'See It Now'" chapter in this article), starring David Strathairn as Murrow and George Clooney as Fred Friendly, co-producer of See It Now, Murrow's show. Test audiences felt that the actor who portrayed Joseph McCarthy was overacting; they were unaware that only archive footage of the actual Joseph McCarthy was used in the film.

- In Wu Ming's novel 54, Cary Grant and David Niven make harsh comments on McCarthy's sloppy way of dressing. At the end of the novel Frances Farmer's "ghost" (in brackets because she wasn't actually dead at the time the novel is set) appears to Grant and expresses relief after McCarthy's demise.

Notes

- ^ "Executive Sessions Of The Senate Permanent Subcommittee On Investigations Of The Committee On Government Operations" (PDF). 1954. Retrieved 2006-06-29."His freewheeling style caused both the Senate and the Sub-committee to revise the rules governing future investigations, and prompted the courts to act to protect the Constitutional rights of witnesses at Congressional hearings."

- ^

The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company. 2000.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b

Herman, Arthur (1999). Joseph McCarthy: Reexamining the Life and Legacy of America's Most Hated Senator. Free Press. pp. pg. 30. ISBN 0-684-83625-4.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^

Morgan, Ted (2003). "Judge Joe; How the youngest judge in Wisconsin's history became the country's most notorious senator". Legal Affairs. Retrieved 2006-08-02.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^

Beichman, Arnold (2006). "The Politics of Personal Self-Destruction". Policy Review. Retrieved 2006-08-02.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Reeves, "Life and Times pp 116-119

- ^ Herman, Arthur (2000). Joseph McCarthy: Reexamining the Life and Legacy of America's Most Hated Senator. Free Press. ISBN 0-684-83625-4.

- ^

O'Brien, Michael (2005). John F. Kennedy: A Biography. St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 0312357451.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b

"Congressional Record, 81st Congress, 2nd Session". West Virginia Division of Culture and History. February 20, 1950. Retrieved 2006-08-11.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ^

Fried, Richard M. (1990). Nightmare in Red: The McCarthy Era in Perspective. Oxford University Press. pp. pg. 124. ISBN 0-19-504361-8.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

Fried, Richard M. (1990). Nightmare in Red: The McCarthy Era in Perspective. Oxford University Press. pp. pg. 128. ISBN 0-19-504361-8.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

Griffith, Robert (1970). The Politics of Fear: Joseph R. McCarthy and the Senate. University of Massachusetts Press. pp. pp 127-129. ISBN 0-87023-555-9.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^

Herman, Arthur (2000). Joseph McCarthy: Reexamining the Life and Legacy of America's Most Hated Senator. Free Press. pp. pg. 233. ISBN 0-684-83625-4.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^

Herman, Arthur (2000). Joseph McCarthy: Reexamining the Life and Legacy of America's Most Hated Senator. Free Press. pp. pg. 131. ISBN 0-684-83625-4.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^

Wicker, Tom (2002). Dwight D. Eisenhower: The American Presidents Series. Times Books. pp. pg. 15. ISBN 0-8050-6907-0.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

Griffith, Robert (1970). The Politics of Fear: Joseph R. McCarthy and the Senate. University of Massachusetts Press. pp. pp 188+. ISBN 0-87023-555-9.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^

Fried, Albert (1997). McCarthyism, The Great American Red Scare: A Documentary History. Oxford University Press. pp. pp 182-184. ISBN 0-19-509701-7.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

Powers, Richard Gid (1998). Not Without Honor: The History of American Anticommunism. Yale University Press. pp. pg. 263. ISBN 0-300-07470-0.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^

Parmet, Herbert S. (1998). Eisenhower and the American Crusades. Transaction Publishers. pp. pp 248, 337, 577. ISBN 0-7658-0437-9.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^

Fried, Richard M. (1990). Nightmare in Red: The McCarthy Era in Perspective. Oxford University Press. pp. pg. 134. ISBN 0-19-504361-8.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

Heil, Alan L. (2003). Voice of America: A History. Columbia University Press. pp. pg. 53. ISBN 0-231-12674-3.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

Heil, Alan L. (2003). Voice of America: A History. Columbia University Press. pp. pg. 56. ISBN 0-231-12674-3.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

Griffith, Robert (1970). The Politics of Fear: Joseph R. McCarthy and the Senate. University of Massachusetts Press. pp. pg. 216. ISBN 0-87023-555-9.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^

"Ike, Milton, and the McCarthy Battle". Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial Commission. Retrieved 2006-08-09.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ Often misidentified as "Reds in Our Churches"; see this versus this.

- ^

Griffith, Robert (1970). The Politics of Fear: Joseph R. McCarthy and the Senate. University of Massachusetts Press. pp. pg. 233. ISBN 0-87023-555-9.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^

Stone, Geoffrey R. (2004). Perilous Times: Free Speech in Wartime from the Sedition Act of 1798 to the War on Terrorism. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. pg. 384. ISBN 0-393-05880-8.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^

Fried, Richard M. (1990). Nightmare in Red: The McCarthy Era in Perspective. Oxford University Press. pp. pg. 138. ISBN 0-19-504361-8.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

Rovere, Richard H. (1959). Senator Joe McCarthy. University of California Press. pp. pg. 30. ISBN 0-520-20472-7.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^

Fried, Richard M. (1990). Nightmare in Red: The McCarthy Era in Perspective. Oxford University Press. pp. pg. 138. ISBN 0-19-504361-8.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ '

Rovere, Richard H. (1959). Senator Joe McCarthy. University of California Press. pp. pg. 30. ISBN 0-520-20472-7.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^

Powers, Richard Gid (1998). Not Without Honor: The History of American Anticommunism. Yale University Press. pp. pg. 271. ISBN 0-300-07470-0.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^

Fried, Richard M. (1990). Nightmare in Red: The McCarthy Era in Perspective. Oxford University Press. pp. pg. 138. ISBN 0-19-504361-8.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

Cook, Fred J. (1971). The Nightmare Decade: The Life and Times of Senator Joe McCarthy. Random House. pp. pg. 536. ISBN 0-394-46270-x.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

Griffith, Robert (1970). The Politics of Fear: Joseph R. McCarthy and the Senate. University of Massachusetts Press. pp. pg. 259. ISBN 0-87023-555-9.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^

"Transcript - See it Now: A Report on Senator Joseph R. McCarthy". CBS-TV. March 9, 1954. Retrieved 2006-08-11.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

Woods, Randall Bennett (1995). Fulbright: A Biography. Cambridge University Press. pp. pg. 187. ISBN 0-521-48262-3.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^

Griffith, Robert (1970). The Politics of Fear: Joseph R. McCarthy and the Senate. University of Massachusetts Press. pp. pp 277+. ISBN 0-87023-555-9.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^

Rovere, Richard H. (1959). Senator Joe McCarthy. University of California Press. pp. pp 229-230. ISBN 0-520-20472-7.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^

"Censure of Senator Joseph McCarthy (1954)". The United States Department of State. Retrieved 2006-08-10.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^

Griffith, Robert (1970). The Politics of Fear: Joseph R. McCarthy and the Senate. University of Massachusetts Press. pp. pg. 310. ISBN 0-87023-555-9.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^

Griffith, Robert (1970). The Politics of Fear: Joseph R. McCarthy and the Senate. University of Massachusetts Press. pp. pg. 318. ISBN 0-87023-555-9.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^

Cook, Fred J. (1971). The Nightmare Decade: The Life and Times of Senator Joe McCarthy. Random House. pp. pg. 537. ISBN 0-394-46270-x.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Coulter, Ann (2003). Treason: Liberal Treachery from the Cold War to the War on Terrorism. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 1400050324.

- ^ Grigg, William Norman (June 16, 2003). "McCarthy's "Witches"". The New American. Retrieved 2006-08-28.

- ^

Evans, M. Stanton (May 30, 1997). "McCarthyism: Waging the Cold War in America". Human Events. Retrieved 2006-08-28.; also of note is:

Evans, M. Stanton (not yet released). Blacklisted By History: The Real Story of Joseph McCarthy and His Fight Against America's Enemies. Crown Forum. ISBN 140008105X.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^

Buckley Jr., William F. (1999). The Red Hunter: a Novel Based on the Life of Senator Joe McCarthy. Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0316115894.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

Haynes, John Earl (2000). Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300084625.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^

Weinstein, Allen (2000). The Haunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America--The Stalin Era. Modern Library. ISBN 0375755365.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^

Drum, Kevin (June 20, 2003). "Sex And Communism". Washington Monthly. Retrieved 2006-09-07.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

Hari, Johann (March 26, 2004). "The Exhumation of Joe McCarthy". History News Network. Retrieved 2006-09-07.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Haynes, John Earl (2006). "Senator Joseph McCarthy's Lists and Venona". Retrieved 2006-08-31.

- ^ Apparently never accused of anything by McCarthy; Venona and other evidence indicates Soviet espionage activity.

(Haynes, John Earl (2000). Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300084625.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)) - ^

Questioned by McCarthy in a closed subcommittee session but apparently never accused of anything; Venona and other evidence indicates Soviet espionage activity.

(Puddington, Arch (1996). "Red Menace - Really". National Review. 48 (6): 46.,

Haynes & Klehr. Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America. ISBN 0300084625.,

Andrew, Christopher and Mitrokhin, Vasili (2000). The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB. Basic Books. ISBN 0465003125.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)) - ^

Came under suspicion in 1945 in the "Amerasia affair", apparently only mentioned in passing by McCarthy; evidence from Venona indicates Soviet espionage activity.

(Darsey, James (1997). The Prophetic Tradition and Radical Rhetoric in America. New York University Press. pp. pg. 134. ISBN 0814719244.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help), Haynes & Klehr. Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America. ISBN 0300084625.) - ^ Accused of spying by Elizabeth Bentley and questioned before HUAC in 1948, briefly mentioned by McCarthy in 1951; Venona and other evidence indicates Soviet espionage activity. (Haynes & Klehr. Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America. ISBN 0300084625., McCarthy, Joseph (1953). Major Speeches and Debates of Senator Joe McCarthy Delivered in the United States Senate, 1950-1951. U. S. Government Printing Office. ISBN 0879683082.)

- ^ Called "a notorious international Communist." by Congressman Alvin O'Konski (who was drawing from an article in a Fascist Madrid newspaper) in 1947, McCarthy repeated the charge in a 1950 speech. No evidence indicates any covert Communist affiliation. (Griffith, Robert (1970). The Politics of Fear: Joseph R. McCarthy and the Senate. University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 0-87023-555-9., McCarthy, Joseph (1953). Major Speeches and Debates of Senator Joe McCarthy Delivered in the United States Senate, 1950-1951. U. S. Government Printing Office. ISBN 0879683082.)

- ^ Accused of being a Communist by McCarthy in 1956; no new evidence indicates any Communist affiliation. ("Testimony, The Richard J. O'Melia Collection". Hesburgh Library at the University of Notre Dame.)

- ^ Accused of being a Communist by McCarthy in 1950 (on the basis of a book Hanson wrote during WWII praising Communist Chinese soldiers); No evidence indicates any covert Communist affiliation. (Cook, Fred J. (1971). The Nightmare Decade: The Life and Times of Senator Joe McCarthy. Random House. ISBN 039446270X.)

- ^

Investigated by HUAC in 1949, accused of being a Communist by McCarthy in 1950; Venona and other evidence indicates Soviet espionage activity.

(McReynolds, Rosalee (Winter 1990/91). "The Progressive Librarians Council and Its Founders". Progressive Librarian.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help), Haynes & Klehr. Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America. ISBN 0300084625., Cook, Fred J. (1990). The Nightmare Decade; The Life and Times of Senator Joe McCarthy. Random House. ISBN 0-394-46270-x.) - ^ One of the China Hands accused by many conservatives of "losing China to the Communists," often accused of espionage or disloyalty by McCarthy. No new evidence indicates any covert Communist affiliation. (Fried, Richard M. (1990). Nightmare in Red: The McCarthy Era in Perspective. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195043618.)

- ^ Questioned by Roy Cohn at the Army Signal Corp hearings but apparently never accused of anything; evidence from Venona indicates Soviet espionage activity. ("Army Signal Corps—Subversion and Espionage, October 22" (PDF). Executive Sessions Of The Senate Permanent Subcommittee On Investigations Of The Committee On Government Operations; Vol. 3. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1953., Haynes & Klehr. Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America. ISBN 0300084625.)

- ^

Accused of being a Communist by McCarthy in 1954 after an FBI informant identified her as a CPUSA member, she claimed ignorance and mistaken identity. Later evidence seemed to indicate that her name and address were on file with the CPUSA as a member.

Herman, Arthur (1999). Joseph McCarthy: Reexamining the Life and Legacy of America's Most Hated Senator. Free Press. pp. pp 333+. ISBN 0-684-83625-4.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^

Among the security risks McCarthy brought before the Tydings Committee; Vassiliev evidence indicates Soviet espionage activity.

(Weinstein, Allen (2000). The Haunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America--The Stalin Era. Modern Library. ISBN 0375755365.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help), Haynes, John Earl (2006). "Senator Joseph McCarthy's Lists and Venona". Retrieved 2006-08-31.) - ^

Accused of espionage by McCarthy in 1950 (drawing from confidential FBI files); no new evidence exists of any Communist affiliation.

(Cox, John Stuart and Theoharis, Athan G. (1988). The Boss: J. Edgar Hoover and the Great American Inquisition. Temple University Press. ISBN 0-87722-532-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)) - ^ Accused of espionage in 1948 and convicted of perjury in 1950, mentioned in speeches by McCarthy in 1951. (May, Gary (1994). Un-American Activities: The Trials of William Remington. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504980-2., McCarthy, Joseph (1953). Major Speeches and Debates of Senator Joe McCarthy Delivered in the United States Senate, 1950-1951. U. S. Government Printing Office. ISBN 0879683082.)

- ^ One of the China Hands accused by McCarthy and many others of "losing China to the Communists"; no new evidence indicates any covert Communist affiliation.

References and additional reading

Scholarly secondary sources

- Bayley, Edwin R. (1981). Joe McCarthy and the Press. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-08624-0.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Crosby, Donald F. (1978). God, Church, and Flag: Senator Joseph R. McCarthy and the Catholic Church, 1950-1957. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-1312-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Daynes, Gary (1997). Making Villains, Making Heroes: Joseph R. McCarthy, Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Politics of American Memory. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-8153-2992-X.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Freeland, Richard M. (1985). The Truman Doctrine and the Origins of McCarthyism: Foreign Policy, Domestic Politics, and Internal Security, 1946-1948. New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-2576-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Fried, Richard M. (1977). Men Against McCarthy. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-08360-2.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Fried, Richard M. (1990). Nightmare in Red: The McCarthy Era in Perspective. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504361-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Andrea Friedman, "The Smearing of Joe McCarthy: The Lavender Scare, Gossip, and Cold War Politics" American Quarterly 57.4 (2005) 1105-1129. online in Project Muse.

- Griffith, Robert (1970). The Politics of Fear: Joseph R. McCarthy and the Senate. University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 0-87023-555-9.

- Herman, Arthur (1999). Joseph McCarthy: Reexamining the Life and Legacy of America's Most Hated Senator. Free Press. ISBN 0-684-83625-4.

- Latham, Earl (1969). Communist Controversy in Washington: From the New Deal to McCarthy. Macmillan Publishing Company. ISBN 0-689-70121-7.

- O'Brien, Michael (1981). McCarthy and McCarthyism in Wisconsin. Olympic Marketing Corp. ISBN 0-8262-0319-1.

- Oshinsky, David M. (1976). Senator Joseph McCarthy and the American Labor Movement. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0-8262-0188-1.

- Oshinsky, David M. (2005). A Conspiracy So Immense: The World of Joe McCarthy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515424-X.

- Rosteck, Thomas (1994). See It Now Confronts McCarthyism: Television Documentary and the Politics of Representation. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-5191-4.

- Reeves, Thomas C. (1982). The Life and Times of Joe McCarthy: A Biography. Madison Books. ISBN 1-56833-101-0.

- Rovere, Richard H. (1959). Senator Joe McCarthy. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20472-7.

Other secondary sources

- Belfrage, Cedric (1989). The American Inquisition, 1945-1960: A Profile of the "McCarthy Era". Thunder's Mouth Press. ISBN 0-938410-87-3.

- Coulter, Ann (2003). Treason: Liberal Treachery from the Cold War to the War on Terrorism. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 1-4000-5032-4.

- Andrew, Christopher and Mitrokhin, Vasili (2000). The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB. Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-00312-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ranville, Michael (1996). To Strike at a King: The Turning Point in the McCarthy Witch-Hunt. Momentum Books Limited. ISBN 1-879094-53-3.

Primary sources

- "Senate Committee Transcripts, 107th Congress". Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs. Retrieved 2006-08-11.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - "Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum". Retrieved 2006-08-11.

- "Censure of Senator Joseph McCarthy (1954)". The United States Department of State. Retrieved 2006-08-10.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help)</ref> - McCarthy, Joseph. "Major Speeches and Debates of Senator Joe McCarthy Delivered in the United States Senate, 1950–1951". Questia Online Library. Retrieved 2006-08-11.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - McCarthy, Joseph (1951). America's Retreat from Victory, the Story of George Catlett Marshall. Devin-Adair. ASIN B0007DRHP6.

- McCarthy, Joseph (1952). McCarthyism, the Fight for America. Devin-Adair. ASIN B0007DRBZ2.

- Watkins, Arthur Vivian (1969). Enough Rope: The inside story of the censure of Senator Joe McCarthy... Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-283101-5.

- Fried, Albert (1996). McCarthyism, The Great American Red Scare: A Documentary History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509701-7.

- Edward R. Murrow & Fred W. Friendly (Producers) (1991). Edward R. Murrow: The McCarthy Years (DVD (from 'See it Now' TV News show)). USA: CBS News/Docurama.

External links

- BBC coverage

- The History Net page on McCarthy

- The McCarthy-Welch exchange

- Joseph McCarthy Papers, Marquette University Library

- FBI Memo Referencing 206 Communists in Government

- Infoage Information on McCarthy's investigations of the Signal Corps, including transcripts of the hearings and more recent interviews.

- Transcript: "A Report on Senator Joseph R. McCarthy" - Edward R. Murrow, See It Now, CBS Television, March 9, 1954 via UC Berkeley library

- Transcript: "Joseph R. McCarthy: Rebuttal to Edward R. Murrow", See It Now, CBS Television, April 6, 1954 via UC Berkeley library

Defense of McCarthy:

- By Human Events Online, a conservative weekly:

- By The New American, John Birch Society:

- By Opinion Editorials, a conservative website:

Criticism of McCarthy:

- Excerpt from Richard Rovere's book Senator Joe McCarthy

- Essay on McCarthyism and modern threats to liberty

- Critical reviews of Ann Coulter's defense of McCarthy, Treason:

- McCarthy's Early Years