Nazism: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m Reverted edits by Rachelseagren (talk) to last version by HenryGarden1000 |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{redirect|National Socialism|other ideologies and groups called National Socialism}} |

{{redirect|National Socialism|other ideologies and groups called National Socialism}} |

||

{{redirect|Nazi}} |

{{redirect|Nazi}} |

||

[[File:Steve Bannon 2010.jpg|thumb]] |

|||

{{pp-semi-indef}} |

{{pp-semi-indef}} |

||

{{pp-move-indef}} |

{{pp-move-indef}} |

||

Revision as of 07:46, 30 January 2017

| Part of a series on |

| Nazism |

|---|

National Socialism (Template:Lang-de), more commonly known as Nazism (/ˈnɑːtsɪzəm, ˈnæ-/[1]), is the ideology and practice associated with the 20th-century German Nazi Party and Nazi Germany, as well as other far-right groups. Usually characterised as a form of fascism that incorporates scientific racism and antisemitism, Nazism developed out of the influences of Pan-Germanism, the Völkisch German nationalist movement and the anti-communist Freikorps paramilitary groups that emerged during the Weimar Republic after German defeat in World War I.

Nazism subscribed to theories of racial hierarchy and Social Darwinism, identifying Germans as part of what Nazis regarded as an Aryan or Nordic master race.[2] It aimed to overcome social divisions and create a homogeneous society, unified on the basis of "racial purity" (Volksgemeinschaft). The Nazis aimed to unite all Germans living in historically German territory, as well as gain additional lands for German expansion under the doctrine of Lebensraum, while excluding those deemed either to be community aliens or belonging to an "inferior" race. The term "National Socialism" arose out of attempts to create a nationalist redefinition of "socialism", as an alternative to both international socialism and free market capitalism. Nazism rejected the Marxist concept of class struggle, opposed cosmopolitan internationalism, and sought to convince all parts of a new German society to subordinate their personal interests to the "common good" and to accept the priority of political interests in economic organisation.[3]

The Nazi Party's precursor, the Pan-German nationalist and anti-Semitic German Workers' Party, was founded on 5 January 1919. By the early 1920s, Adolf Hitler assumed control of the organisation and renamed it the National Socialist German Workers' Party (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, NSDAP) to broaden its appeal. The National Socialist Program, adopted in 1920, called for a united Greater Germany that would deny citizenship to Jews or those of Jewish descent, while also supporting land reform and the nationalisation of some industries. In Mein Kampf, written in 1924, Hitler outlined the antisemitism and anti-communism at the heart of his political philosophy, as well as his disdain for parliamentary democracy and his belief in Germany’s right to territorial expansion.

In 1933, with the support of traditional conservative nationalists, Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany and the Nazis gradually established a one-party state, under which Jews, political opponents and other "undesirable" elements were marginalised, with several millions eventually imprisoned and killed. Hitler purged the party’s more socially and economically radical factions in the mid-1934 Night of the Long Knives and, after the death of President Hindenburg, political power was concentrated in his hands, as Führer or "leader". Following the Holocaust and German defeat in World War II, only a few fringe racist groups, usually referred to as neo-Nazis, still describe themselves as following National Socialism.

Etymology

The full name of Adolf Hitler's party was Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (National-Socialist German Workers' Party; NSDAP). The shorthand Nazi was formed from the first two syllables of the German pronunciation of the word "national" (IPA: [na-tsi̯-o-ˈnaːl]).[4]

The term was in use before the rise of the NSDAP as a colloquial and derogatory word for a backwards peasant, characterizing an awkward and clumsy person. It derived from Ignaz, being a shortened version of Ignatius,[5][6] a common name in Bavaria, the area from which the Nazis emerged. Opponents seized on this and shortened the first word of the party's name, Nationalsozialistische, to the dismissive "Nazi".[6][7][8][9]

The NSDAP briefly adopted the Nazi designation, attempting to reappropriate the term, but soon gave up this effort and generally avoided it while in power.[7][8] The use of "Nazi Germany", "Nazi regime", and so on was popularised by German exiles abroad. From them, the term spread into other languages and was eventually brought back to Germany after World War II.[7] In English, Nazism is a common name for the ideology the party advocated; a rarer alternative spelling, though representing a common pronunciation, is Naziism (/ˈnɑːtsi.ɪzəmˌ ˈnæ-/).[10]

Position in the political spectrum

The majority of scholars identify Nazism in practice as a form of far-right politics.[11] Far-right themes in Nazism include the argument that superior people have a right to dominate over other people and purge society of supposed inferior elements.[12] Adolf Hitler and other proponents officially portrayed Nazism as being neither left- nor right-wing, but syncretic.[13][14] Hitler in Mein Kampf directly attacked both left-wing and right-wing politics in Germany, saying:

Today our left-wing politicians in particular are constantly insisting that their craven-hearted and obsequious foreign policy necessarily results from the disarmament of Germany, whereas the truth is that this is the policy of traitors ... But the politicians of the Right deserve exactly the same reproach. It was through their miserable cowardice that those ruffians of Jews who came into power in 1918 were able to rob the nation of its arms.[15]

Hitler, when asked whether he supported the "bourgeois right-wing", claimed that Nazism was not exclusively for any class, and indicated that it favoured neither the left nor the right, but preserved "pure" elements from both "camps", stating: "From the camp of bourgeois tradition, it takes national resolve, and from the materialism of the Marxist dogma, living, creative Socialism".[16]

The Nazis were strongly influenced by the post-World War I far right in Germany, which held common beliefs such as anti-Marxism, anti-liberalism, and antisemitism, along with nationalism, contempt towards the Treaty of Versailles, and condemnation of the Weimar Republic for signing the armistice in November 1918 that later led to their signing of the Treaty of Versailles.[17] A major inspiration for the Nazis were the far-right nationalist Freikorps, paramilitary organisations that engaged in political violence after World War I.[17] Initially, the post-World War I German far right was dominated by monarchists, but the younger generation, who were associated with Völkisch nationalism, were more radical and did not express any emphasis on the restoration of the German monarchy.[18] This younger generation desired to dismantle the Weimar Republic and create a new radical and strong state based upon a martial ruling ethic that could revive the "Spirit of 1914" that was associated with German national unity (Volksgemeinschaft).[18]

The Nazis, the far-right monarchist, reactionary German National People's Party (DNVP), and others, such as monarchist officers of the German Army and several prominent industrialists, formed an alliance in opposition to the Weimar Republic on 11 October 1931 in Bad Harzburg, officially known as the "National Front", but commonly referred to as the Harzburg Front.[19] The Nazis stated the alliance was purely tactical and there remained substantial differences with the DNVP. The Nazis described the DNVP as a bourgeois party and called themselves an anti-bourgeois party.[19] After the elections in 1932, the alliance broke after the DNVP lost many of its seats in the Reichstag. The Nazis denounced them as "an insignificant heap of reactionaries".[20] The DNVP responded by denouncing the Nazis for their socialism, their street violence, and the "economic experiments" that would take place if the Nazis rose to power.[21]

Kaiser Wilhelm II, who was pressured to abdicate the throne and flee into exile amidst an attempted communist revolution in Germany, initially supported the Nazi Party. His four sons, including Prince Eitel Friedrich and Prince Oskar, became members of the Nazi Party, in hopes that in exchange for their support, the Nazis would permit the restoration of the monarchy.[22]

There were factions in the Nazi Party, both conservative and radical.[23] The conservative Nazi Hermann Göring urged Hitler to conciliate with capitalists and reactionaries.[23] Other prominent conservative Nazis included Heinrich Himmler and Reinhard Heydrich.[24]

The radical Nazi Joseph Goebbels hated capitalism, viewing it as having Jews at its core, and he stressed the need for the party to emphasise both a proletarian and national character. Those views were shared by Otto Strasser, who later left the Nazi Party in the belief that Hitler had betrayed the party's socialist goals by allegedly endorsing capitalism.[23] Large segments of the Nazi Party staunchly supported its official socialist, revolutionary, and anti-capitalist positions and expected both a social and economic revolution upon the party's gaining power in 1933.[25] Many of the million members of the Sturmabteilung (SA) were committed to the party's official socialist program.[25] The leader of the SA, Ernst Röhm, pushed for a "second revolution" (the "first revolution" being the Nazis' seizure of power) that would entrench the party's official socialist program. Further, Röhm desired that the SA absorb the much smaller German Army into its ranks under his leadership.[25]

Before he became an anti-Semite and a Nazi, Hitler had lived a bohemian lifestyle as a wandering watercolour artist in Austria and southern Germany, though he maintained elements of it later in life.[26] Hitler served in World War I. After the war, his battalion was absorbed by the Bavarian Soviet Republic from 1918 to 1919, where he was elected Deputy Battalion Representative. According to the historian Thomas Weber, Hitler attended the funeral of communist Kurt Eisner (a German Jew), wearing a black mourning armband on one arm and a red communist armband on the other,[27] which he took as evidence that Hitler's political beliefs had not yet solidified.[27] In Mein Kampf, Hitler never mentioned any service with the Bavarian Soviet Republic, and stated that he became an anti-Semite in 1913 in Vienna. This statement has been disputed with the contention he was not an anti-Semite at that time.[28]

Hitler altered his political views in response to the Treaty of Versailles of June 1919, and it was then that he became an anti-Semitic, German nationalist.[28] As a Nazi, Hitler had expressed opposition to capitalism, having regarded capitalism as having Jewish origins. He accused capitalism of holding nations ransom in the interests of a parasitic cosmopolitan rentier class.[29]

Hitler took a pragmatic position between the conservative and radical factions of the Nazi Party, in that he accepted private property and allowed capitalist private enterprises to exist so long as they adhered to the goals of the Nazi state. However, if a capitalist private enterprise resisted Nazi goals, he sought to destroy it.[23] Upon the Nazis achieving power, Röhm's SA began attacks against individuals deemed to be associated with conservative reaction, without Hitler's authorisation.[30] Hitler considered Röhm's independent actions to be violating and threatening his leadership, as well as jeopardising the regime by alienating the conservative President Paul von Hindenburg and the conservative-oriented German Army.[31] This resulted in Hitler purging Röhm and other radical members of the SA in what came to be known as the Night of the Long Knives.[31]

Although he opposed communist ideology, Hitler on numerous occasions publicly praised the Soviet Union's leader Joseph Stalin and Stalinism.[32] Hitler commended Stalin for seeking to purify the Communist Party of the Soviet Union of Jewish influences, noting Stalin's purging of Jewish communists such as Leon Trotsky, Grigory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev, and Karl Radek.[33] While Hitler always intended to bring Germany into conflict against the Soviet Union to gain Lebensraum (living space), he supported a temporary strategic alliance between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union to form a common anti-liberal front to crush liberal democracies, particularly France.[32]

Origins

Völkisch nationalism

One of the most significant ideological influences on the Nazis was the German nationalist Johann Gottlieb Fichte, whose works had served as inspiration to Hitler and other Nazi members, including Dietrich Eckart and Arnold Fanck.[34] In Speeches to the German Nation (1808), written amid Napoleonic France's occupation of Berlin, Fichte called for a German national revolution against the French occupiers, making passionate public speeches, arming his students for battle against the French, and stressing the need for action by the German nation to free itself.[35] Fichte's nationalism was populist and opposed to traditional elites, spoke of the need of a "People's War" (Volkskrieg), and put forth concepts similar to those the Nazis adopted.[35] Fichte promoted German exceptionalism and stressed the need for the German nation to be purified (including purging the German language of French words, a policy that the Nazis undertook upon rising to power).[35]

Another important figure in pre-Nazi völkisch thinking was Wilhelm Heinrich Riehl, whose work—Land und Leute (Land and People, written between 1857 and 1863)—collectively tied the organic German Volk to its native landscape and nature, a pairing which stood in stark opposition to the mechanical and materialistic civilisation developing as a result of industrialisation.[36] Geographers Friedrich Ratzel and Karl Haushofer borrowed from Riehl's work as did Nazi ideologues Alfred Rosenberg and Paul Schultze-Naumburg; both of whom employed some of Riehl’s philosophy in arguing that "each nation-state was an organism that required a particular living space to survive".[37] Riehl’s influence is overtly discernible in the Blut und Boden (Blood and Soil) philosophy introduced by Oswald Spengler, which the Nazi agriculturalist Walther Darré and other prominent Nazis adopted.[38][39]

Völkisch nationalism denounced soulless materialism, individualism, and secularised urban industrial society, while advocating a "superior" society based on ethnic German "folk" culture and German "blood".[40] It denounced foreigners and foreign ideas, and declared that Jews, Freemasons, and others were "traitors to the nation" and unworthy of inclusion.[41] Völkisch nationalism saw the world in terms of natural law and romanticism; it viewed societies as organic, extolling the virtues of rural life, condemning the neglect of tradition and decay of morals, denounced the destruction of the natural environment, and condemned "cosmopolitan" cultures such as Jews and Romani.[42]

During the era of Imperial Germany, Völkisch nationalism was overshadowed by both Prussian patriotism and the federalist tradition of various states therein.[43] The events of World War I, including the end of the Prussian monarchy in Germany, resulted in a surge of revolutionary Völkisch nationalism.[44] The Nazis supported such revolutionary Völkisch nationalist policies[43] and claimed that their ideology was influenced by the leadership and policies of German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, the founder of the German Empire.[45] The Nazis declared that they were dedicated to continuing the process of creating a unified German nation state that Bismarck had begun and desired to achieve.[46] While Hitler was supportive of Bismarck's creation of the German Empire, he was critical of Bismarck's moderate domestic policies.[47] On the issue of Bismarck's support of a Kleindeutschland ("Lesser Germany", excluding Austria) versus the Pan-German Großdeutschland ("Greater Germany") of the Nazis, Hitler stated that Bismarck's attainment of Kleindeutschland was the "highest achievement" Bismarck could have achieved "within the limits possible of that time".[48] In Mein Kampf (My Struggle), Hitler presented himself as a "second Bismarck".[48]

During his youth in Austria, Hitler was politically influenced by Austrian Pan-Germanist proponent Georg Ritter von Schönerer, who advocated radical German nationalism, antisemitism, anti-Catholicism, anti-Slavism, and anti-Habsburg views.[49] From von Schönerer and his followers, Hitler adopted for the Nazi movement the Heil greeting, the Führer title, and the model of absolute party leadership.[49] Hitler was also impressed with the populist antisemitism and anti-liberal bourgeois agitation of Karl Lueger, who as the mayor of Vienna during Hitler's time in the city used a rabble-rousing oratory style that appealed to the wider masses.[50] Unlike von Schönerer, however, Lueger was not a German nationalist, but a pro-Catholic Habsburg supporter.[50]

Racial theories and antisemitism

The concept of the Aryan race, which the Nazis promoted, stems from racial theories asserting that Europeans are the descendants of Indo-Iranian settlers, people of ancient India and ancient Persia.[51] Proponents of this theory based their assertion on the similarity of European words and their meaning to those of Indo-Iranian languages.[51] Johann Gottfried Herder argued that the Germanic peoples held close racial connections with the ancient Indians and ancient Persians, who he claimed were advanced peoples possessing a great capacity for wisdom, nobility, restraint, and science.[51] Contemporaries of Herder used the concept of the Aryan race to draw a distinction between what they deemed "high and noble" Aryan culture versus that of "parasitic" Semitic culture.[51]

Notions of white supremacy and Aryan racial superiority combined in the 19th century, with white supremacists maintaining that certain groups of white people were members of an Aryan "master race" that is superior to other races, and particularly superior to the Semitic race, which they associated with "cultural sterility".[51] Arthur de Gobineau, a French racial theorist and aristocrat, blamed the fall of the ancien régime in France on racial degeneracy caused by racial intermixing, which he argued destroyed the purity of the Aryan race, a term which he reserved only for Germanic people.[52][53] Gobineau's theories, which attracted a strong following in Germany,[52] emphasised the existence of an irreconcilable polarity between Aryan (Germanic) and Jewish cultures.[51]

Aryan mysticism claimed that Christianity originated in Aryan religious tradition and that Jews had usurped the legend from Aryans.[51] Houston Stewart Chamberlain, an English proponent of racial theory, supported notions of Germanic supremacy and antisemitism in Germany.[52] Chamberlain's work, The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century (1899), praised Germanic peoples for their creativity and idealism while asserting that the Germanic spirit was threatened by a "Jewish" spirit of selfishness and materialism.[52] Chamberlain used his thesis to promote monarchical conservatism while denouncing democracy, liberalism, and socialism.[52] The book became popular, especially in Germany.[52] Chamberlain stressed the need of a nation to maintain racial purity in order to prevent degeneration, and argued that racial intermingling with Jews should never be permitted.[52] In 1923, Chamberlain met Hitler, whom he admired as a leader of the rebirth of the free spirit.[54] Madison Grant's work The Passing of the Great Race (1916) advocated Nordicism and proposed using a eugenic program to preserve the Nordic race. After reading the book, Hitler called it "my Bible".[55]

In Germany, the idea of Jews economically exploiting Germans became prominent upon the foundation of Germany due to the ascendance of many wealthy Jews into prominent positions upon the unification of Germany in 1871.[56] Empirical evidence demonstrates that from 1871 to the early 20th century, German Jews were overrepresented in Germany's upper and middle classes while they were underrepresented in Germany's lower class, particularly in the fields of work of agricultural and industrial labour.[57] German Jewish financiers and bankers played a key role in fostering Germany's economic growth from the 1871 to 1913, and such Jewish financiers and bankers benefited enormously from this boom. In 1908, amongst the twenty-nine wealthiest German families with aggregate fortunes of up to 55 million marks at the time, five were Jewish, and the Rothschilds were the second wealthiest German family.[58] The predominance of Jews in Germany's banking, commerce, and industry sectors in this time period was very high with consideration to Jews being estimated to have accounted for 1% of the population of Germany.[56] This overrepresentation of Jews in these areas created resentment by non-Jewish Germans during periods of economic crisis.[57] The 1873 stock market crash and ensuing depression resulted in a spate of attacks on alleged Jewish economic dominance in Germany and increased antisemitism.[57]

At this time period in the 1870s, German Völkisch nationalism began to adopt anti-Semitic and racist themes and was adopted by a number of radical right political movements.[59]

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion (1912) was an anti-Semitic forgery created by the secret service of the Russian Empire, the Okhrana. Many anti-Semites believed it was real and the Protocol became widely popular after World War I.[60] The Protocols claimed that there was a secret international Jewish conspiracy to take over the world.[61] Hitler had been introduced to The Protocols by Alfred Rosenberg, and from 1920 onward, Hitler focused his attacks on claiming that Judaism and Marxism were directly connected, that Jews and Bolsheviks were one and the same, and that Marxism was a Jewish ideology.[62] Hitler believed that The Protocols were authentic.[63]

Radical Antisemitism was promoted by prominent advocates of Völkisch nationalism, including Eugen Diederichs, Paul de Lagarde, and Julius Langbehn.[42] De Lagarde called the Jews a "bacillus, the carrier of decay ... who pollute every national culture ... and destroy all faith with their materialistic liberalism", and he called for the extermination of the Jews.[64] Langbehn called for a war of annihilation of the Jews; his genocidal policies were published by the Nazis and given to soldiers on the front during World War II.[64] One anti-Semitic ideologue of the period, Friedrich Lange, even used the term "national socialism" to describe his own anti-capitalist take on the Völkisch nationalist template.[65]

Johann Gottlieb Fichte accused Jews in Germany of having been, and inevitably continuing to be, a "state within a state" that threatened German national unity.[35] Fichte promoted two options to address this: the first was the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine to impel the Jews to leave Europe.[66] The other option was violence against Jews, saying that the goal would be "to cut off all their heads in one night, and set new ones on their shoulders, which should not contain a single Jewish idea".[66]

Prior to the Nazi ascension to power, Hitler often blamed moral degradation on Rassenschande (racial defilement), a way to assure his followers of his continuing antisemitism, which had been toned down for popular consumption.[67] Prior to the induction of the Nuremberg Race Laws in 1935 by the Nazis, many German nationalists such as Roland Freisler strongly supported laws to ban Rassenschande between Aryans and Jews as racial treason.[67] Even before the laws were officially passed, the Nazis banned sexual relations and marriages between party members and Jews.[68] Party members found guilty of Rassenschande were heavily punished; some members were even sentenced to death.[69]

The Nazis claimed that Bismarck was unable to complete German national unification because of Jewish infiltration of the German parliament, and that their abolition of parliament ended the obstacle to unification.[45] Using the stab-in-the-back myth, the Nazis accused Jews—and other populaces it considered non-German—of possessing extra-national loyalties, thereby exacerbating German antisemitism about the Judenfrage (the Jewish Question), the far-right political canard popular when the ethnic Völkisch movement and their politics of Romantic nationalism for establishing a Großdeutschland were strong.[70][71]

Nazism's racial policy positions may have developed from the views of important biologists of the 19th century, including French biologist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, through Ernst Haeckel's idealist version of Lamarckism and the father of genetics, German botanist Gregor Mendel.[72] However, Haeckel's works were later condemned and banned from bookshops and libraries by the Nazis as inappropriate for "National-Socialist formation and education in the Third Reich". This may have been because of his "monist" atheistic, materialist philosophy, which the Nazis disliked.[73] Unlike Darwinian theory, Lamarckian theory officially ranked races in a hierarchy of evolution from apes while Darwinian theory did not grade races in a hierarchy of higher or lower evolution from apes, simply categorising humans as a whole of all as having progressed in evolution from apes.[72] Many Lamarckians viewed "lower" races as having been exposed to debilitating conditions for too long for any significant "improvement" of their condition in the near future.[74] Haeckel utilised Lamarckian theory to describe the existence of interracial struggle and put races on a hierarchy of evolution, ranging from being wholly human to subhuman.[72]

Mendelian inheritance, or Mendelism, was supported by the Nazis, as well as by mainstream eugenics proponents at the time. The Mendelian theory of inheritance declared that genetic traits and attributes were passed from one generation to another.[75] Proponents of eugenics used Mendelian inheritance theory to demonstrate the transfer of biological illness and impairments from parents to children, including mental disability; others also utilised Mendelian theory to demonstrate the inheritance of social traits, with racialists claiming a racial nature of certain general traits such as inventiveness or criminal behaviour.[76]

Response to World War I and Italian Fascism

During World War I, German sociologist Johann Plenge spoke of the rise of a "National Socialism" in Germany within what he termed the "ideas of 1914" that were a declaration of war against the "ideas of 1789" (the French Revolution).[77] According to Plenge, the "ideas of 1789" that included rights of man, democracy, individualism and liberalism were being rejected in favour of "the ideas of 1914" that included "German values" of duty, discipline, law, and order.[77] Plenge believed that ethnic solidarity (Volksgemeinschaft) would replace class division and that "racial comrades" would unite to create a socialist society in the struggle of "proletarian" Germany against "capitalist" Britain.[77] He believed that the "Spirit of 1914" manifested itself in the concept of the "People's League of National Socialism".[78] This National Socialism was a form of state socialism that rejected the "idea of boundless freedom" and promoted an economy that would serve the whole of Germany under the leadership of the state.[78] This National Socialism was opposed to capitalism due to the components that were against "the national interest" of Germany, but insisted that National Socialism would strive for greater efficiency in the economy.[78] Plenge advocated an authoritarian, rational ruling elite to develop National Socialism through a hierarchical technocratic state.[79] Plenge's ideas formed the basis of Nazism.[77]

Oswald Spengler, a German cultural philosopher, was a major influence on Nazism, although, after 1933, Spengler became alienated from Nazism and was later condemned by the Nazis for criticising Adolf Hitler.[80] Spengler's conception of national socialism and a number of his political views were shared by the Nazis and the Conservative Revolutionary movement.[81] Spengler's views were also popular amongst Italian Fascists, including Benito Mussolini.[82]

Spengler's book The Decline of the West (1918) written during the final months of World War I, addressed the claim of decadence of modern European civilisation, which he claimed was caused by atomising and irreligious individualisation and cosmopolitanism.[80] Spengler's major thesis was that a law of historical development of cultures existed involving a cycle of birth, maturity, ageing, and death when it reaches its final form of civilisation.[80] Upon reaching the point of civilisation, a culture will lose its creative capacity and succumb to decadence until the emergence of "barbarians" creates a new epoch.[80] Spengler considered the Western world as having succumbed to decadence of intellect, money, cosmopolitan urban life, irreligious life, atomised individualisation, and was at the end of its biological and "spiritual" fertility.[80] He believed that the "young" German nation as an imperial power would inherit the legacy of Ancient Rome, lead a restoration of value in "blood" and instinct, while the ideals of rationalism would be revealed as absurd.[80]

Spengler's notions of "Prussian socialism" as described in his book Preussentum und Sozialismus ("Prussiandom and Socialism", 1919), influenced Nazism and the Conservative Revolutionary movement.[81] Spengler wrote: "The meaning of socialism is that life is controlled not by the opposition between rich and poor, but by the rank that achievement and talent bestow. That is our freedom, freedom from the economic despotism of the individual."[81] Spengler adopted the anti-English ideas addressed by Plenge and Sombart during World War I that condemned English liberalism and English parliamentarianism while advocating a national socialism that was free from Marxism and that would connect the individual to the state through corporatist organisation.[80] Spengler claimed that socialistic Prussian characteristics existed across Germany, including creativity, discipline, concern for the greater good, productivity, and self-sacrifice.[83] He prescribed war as a necessity, saying "War is the eternal form of higher human existence and states exist for war: they are the expression of the will to war."[84]

Spengler's definition of socialism did not advocate a change to property relations.[81] He denounced Marxism for seeking to train the proletariat to "expropriate the expropriator", the capitalist, and then to let them live a life of leisure on this expropriation.[86] He claimed that "Marxism is the capitalism of the working class" and not true socialism.[86] True socialism, according to Spengler, would be in the form of corporatism, stating that: "local corporate bodies organised according to the importance of each occupation to the people as a whole; higher representation in stages up to a supreme council of the state; mandates revocable at any time; no organised parties, no professional politicians, no periodic elections".[87]

Wilhelm Stapel, an anti-Semitic German intellectual, utilised Spengler's thesis on the cultural confrontation between Jews as whom Spengler described as a Magian people versus Europeans as a Faustian people.[88] Stapel described Jews as a landless nomadic people in pursuit of an international culture whereby they can integrate into Western civilisation.[88] As such, Stapel claims that Jews have been attracted to "international" versions of socialism, pacifism, or capitalism because as a landless people the Jews have transgressed various national cultural boundaries.[88]

Arthur Moeller van den Bruck was initially the dominant figure of the Conservative Revolutionaries influenced Nazism.[89] He rejected reactionary conservatism, while proposing a new state, that he coined the "Third Reich", which would unite all classes under authoritarian rule.[90] Van den Bruck advocated a combination of the nationalism of the right and the socialism of the left.[91]

Fascism was a major influence on Nazism. The seizure of power by Italian Fascist leader Benito Mussolini in the March on Rome in 1922 drew admiration by Hitler, who less than a month later had begun to model himself and the Nazi Party upon Mussolini and the Fascists.[92] Hitler presented the Nazis as a form of German fascism.[93][94] In November 1923, the Nazis attempted a "March on Berlin", modelled after the March on Rome, which resulted in the failed Beer Hall Putsch in Munich.[95]

Hitler spoke of Nazism being indebted to the success of Fascism's rise to power in Italy.[96] In a private conversation in 1941 he said "the brown shirt would probably not have existed without the black shirt", the "brown shirt" referring to the Nazi militia and the "black shirt" referring to the Fascist militia.[96] He also said in regards to the 1920s "If Mussolini had been outdistanced by Marxism, I don't know whether we could have succeeded in holding out. At that period National Socialism was a very fragile growth."[96]

Other Nazis—especially those at the time associated with the party's more radical wing such as Gregor Strasser, Joseph Goebbels, and Heinrich Himmler—rejected Italian Fascism, accusing it of being too conservative or capitalist.[97] Alfred Rosenberg condemned Italian Fascism for being racially confused and having influences from philosemitism.[98] Strasser criticised the policy of Führerprinzip as being created by Mussolini, and considered its presence in Nazism as a foreign imported idea.[99] Throughout the relationship between Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, a number of lower-ranking Nazis scornfully viewed fascism as a conservative movement that lacked a full revolutionary potential.[99]

Ideology

Nationalism and racialism

German Nazism emphasised German nationalism, including both irredentism and expansionism. Nazism held racial theories based upon the belief of the existence of an Aryan master race that was superior to all other races. The Nazis emphasised the existence of racial conflict between the Aryan race and others—particularly Jews, whom the Nazis viewed as a mixed race that had infiltrated multiple societies, and was responsible for exploitation and repression of the Aryan race. The Nazis also categorised Slavs as Untermensch.[100]

Irredentism and expansionism

The German Nazi Party supported German irredentist claims to Austria, Alsace-Lorraine, the region now known as the Czech Republic, and the territory known since 1919 as the Polish Corridor. A major policy of the German Nazi Party was Lebensraum ("living space") for the German nation based on claims that Germany after World War I was facing an overpopulation crisis and that expansion was needed to end the country's overpopulation within existing confined territory, and provide resources necessary to its people's well-being.[101] Since the 1920s, the Nazi Party publicly promoted the expansion of Germany into territories held by the Soviet Union.[102]

In his early years as the Nazi leader, Hitler had claimed that he would be willing to accept friendly relations with Russia on the tactical condition that Russia agree to return to the borders established by the German–Russian peace agreement of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk signed by Vladimir Lenin of the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic in 1918 which gave large territories held by Russia to German control in exchange for peace.[102] Hitler in 1921 had commended the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk as opening the possibility for restoration of relations between Germany and Russia, saying:

Through the peace with Russia the sustenance of Germany as well as the provision of work were to have been secured by the acquisition of land and soil, by access to raw materials, and by friendly relations between the two lands.

— Adolf Hitler, 1921[102]

Hitler from 1921 to 1922 evoked rhetoric of both the achievement of Lebensraum involving the acceptance of a territorially reduced Russia as well as supporting Russian nationals in overthrowing the Bolshevik government and establishing a new Russian government.[102] Hitler's attitudes changed by the end of 1922, in which he then supported an alliance of Germany with Britain to destroy Russia.[102] Later Hitler declared how far he intended to expand Germany into Russia:

Asia, what a disquieting reservoir of men! The safety of Europe will not be assured until we have driven Asia back behind the Urals. No organized Russian state must be allowed to exist west of that line.

— Adolf Hitler[103]

Policy for Lebensraum planned mass expansion of Germany eastwards to the Ural Mountains.[103][104] Hitler planned for the "surplus" Russian population living west of the Urals to be deported to the east of the Urals.[105]

Racial theories

In its racial categorisation, Nazism viewed what it called the Aryan race as the master race of the world—a race that was superior to all other races.[106] It viewed Aryans as being in racial conflict with a mixed race people, the Jews, whom Nazis identified as a dangerous enemy of the Aryans. It also viewed a number of other peoples as dangerous to the well-being of the Aryan race. In order to preserve the perceived racial purity of the Aryan race, a set of race laws were introduced in 1935 which came to be known as the Nuremberg Laws. At first these laws only prevented sexual relations and marriages between Germans and Jews, but were later extended to the "Gypsies, Negroes, and their bastard offspring", who were described by the Nazis as people of "alien blood".[107][108] Such relations between Aryans (cf. Aryan certificate) and non-Aryans were now punishable under the race laws as Rassenschande or "race defilement".[107] After the war began, the race defilement law was extended to include all foreigners (non-Germans).[109] At the bottom of the racial scale of non-Aryans were Jews, Romani, Slavs[110] and blacks.[111] To maintain the "purity and strength" of the Aryan race, the Nazis eventually sought to exterminate Jews, Romani, Slavs, and the physically and mentally disabled.[110][112] Other groups deemed "degenerate" and "asocial" who were not targeted for extermination, but received exclusionary treatment by the Nazi state, included homosexuals, blacks, Jehovah's Witnesses, and political opponents.[112] One of Hitler's ambitions at the start of the war was to exterminate, expel, or enslave most or all Slavs from central and eastern Europe in order to make living space for German settlers.[113]

A Nazi era school textbook for German students entitled Heredity and Racial Biology for Students written by Jakob Graf described to students the Nazi conception of the Aryan race in a section titled "The Aryan: The Creative Force in Human History".[106] Graf claimed that the original Aryans developed from Nordic peoples who invaded ancient India that resulted in the initial development of Aryan culture there that later spread to ancient Persia and claimed that the Aryan presence in Persia was what was responsible for its development into an empire.[106] He claimed that ancient Greek culture was developed by Nordics due to paintings of the time showing Greeks who were tall, light-skinned, light-eyed, blond-haired people.[106] He said that the Roman Empire was developed by the Italics who were related to the Celts who were a Nordic people.[106] He considered that the vanishing of the Nordic component of the populations in Greece and Rome led to their downfall.[106] The Renaissance was claimed to have developed in the Western Roman Empire because of the Germanic invasions that brought new Nordic blood to the Empire's lands, such as presence of Nordic blood in the Lombards (referred to as Longobards in the book); that remnants of the western Goths were responsible for the creation of the Spanish Empire; and that heritage of Franks, Goths, and Germanic peoples in France was what was responsible for its rise to be a major power.[106] He claimed that the rise of the Russian Empire was due to its leadership by people of Norman descent.[106] He described the rise of Anglo-Saxon societies in North America, South Africa, and Australia, as being the result of the Nordic heritage of Anglo-Saxons.[106] He concluded these points by saying that "Everywhere Nordic creative power has built mighty empires with high-minded ideas, and to this very day Aryan languages and cultural values are spread over a large part of the world, though the creative Nordic blood has long since vanished in many places."[106]

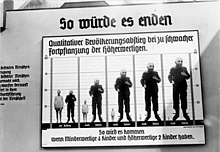

In Nazi Germany, the idea of creating a master race resulted in efforts to "purify" the Deutsche Volk through eugenics; its culmination was compulsory sterilisation or involuntary euthanasia of physically or mentally disabled people. The name given after World War II for the euthanasia programme is Action T4.[114] The ideological justification was Adolf Hitler's view of Sparta (11th century – 195 BC) as the original Völkisch state; he praised their dispassionate destruction of congenitally deformed infants in maintaining racial purity.[115][116] Some non-Aryans enlisted in Nazi organisations like the Hitler Youth and the Wehrmacht, including Germans of African descent[117] and Jewish descent.[118] The Nazis began to implement "racial hygiene" policies as soon as they came to power. The July 1933 "Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring" prescribed compulsory sterilisation for people with a range of conditions thought to be hereditary, such as schizophrenia, epilepsy, Huntington's chorea, and "imbecility". Sterilisation was also mandated for chronic alcoholism and other forms of social deviance.[119] An estimated 360,000 people were sterilised under this law between 1933 and 1939. Although some Nazis suggested that the programme should be extended to people with physical disabilities, such ideas had to be expressed carefully, given that some Nazis had physical disabilities, one example being one of the most powerful figures of the regime, Joseph Goebbels, who had a deformed right leg.[120]

Nazi racial theorist Hans F. K. Günther argued that European peoples were divided into five races: Nordic, Mediterranean, Dinaric, Alpine, and East Baltic.[2] Günther applied a Nordicist conception that Nordics were the highest in the racial hierarchy.[2] In his book Rassenkunde des deutschen Volkes (1922) ("Racial Science of the German People"), Günther recognised Germans as being composed of all five races, but emphasised the strong Nordic heritage among them.[121] Hitler read Rassenkunde des deutschen Volkes, which influenced his racial policy.[122] Gunther believed Slavs belonged to an "East race" and warned against Germans mixing with them.[123]

The Nazis described Jews as being racially mixed group of primarily Near Eastern and Oriental racial types.[124] As such racial groups were concentrated outside of Europe, the Nazis claimed that Jews were "racially alien" to all European peoples and did not have deep racial roots in Europe.[124]

Günther empathised Jews' Near Eastern racial heritage.[125] Günther identified the mass conversion of the Khazars to Judaism in the 8th century as creating the two major branches of the Jewish people, those of primarily Near Eastern racial heritage became the Ashkenazi Jews (that he called Eastern Jews) while those of primarily Oriental racial heritage became the Sephardic Jews (that he called Southern Jews).[126] Günther claimed the Near Eastern type were commercially spirited and artful traders, that the type held strong psychological manipulation skills that aided them in trade.[125] He claimed that the Near Eastern race had been "bred not so much for the conquest and exploitation of nature as it was for the conquest and exploitation of people".[125] Günther described that European peoples had a racially motivated aversion to peoples of Near Eastern racial origin and their traits, and showed as evidence of this multiple examples of depictions of satanic figures with Near Eastern physiognomies in European art.[127]

Hitler's conception of the Aryan Herrenvolk ("Aryan master race") excluded the vast majority of Slavs from central and eastern Europe (i.e., Poles, Russians, Ukrainians, etc.). They were regarded as a race of men not inclined to a higher form of civilisation, which were under an instinctive force that reverted them back to nature. They also regarding the Slavs as having dangerous Jewish and Asiatic, that being Mongol, influences.[128] The Nazis because of this declared Slavs to be Untermenschen (subhumans).[129] Nazi anthropologists attempted to prove scientifically the historical admixture of the Slavs further East. Leading Nazi racial theorist Hans Günther regarded the Slavs as being primarily Nordic centuries ago but over time had mixed with non-Nordic types.[130] There were exceptions for a small percentage of Slavs who were seen to be descended from German settlers and therefore fit to be Germanised and be considered part of the Aryan master race.[131] Hitler described Slavs as "a mass of born slaves who feel the need of a master".[132] The Nazi notion of Slavs being inferior served as legitimising their goal for creating Lebensraum for Germans and other Germanic people in eastern Europe, where millions of Germans and other Germanic settlers would be moved into conquered territories of Eastern Europe, while the original Slavic inhabitants were to be annihilated, removed, or enslaved.[133] Nazi Germany's policy changed towards Slavs in response to military manpower shortages, in which it accepted Slavs to serve in its armed forces within occupied territories, in spite of them being considered subhuman.[134]

Hitler declared that racial conflict against Jews was necessary to save Germany from suffering under them and dismissed concerns about such conflict being inhumane or an injustice:

We may be inhumane, but if we rescue Germany we have achieved the greatest deed in the world. We may work injustice, but if we rescue Germany then we have removed the greatest injustice in the world. We may be immoral, but if our people is rescued we have opened the way for morality.[135]

Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels frequently employed anti-Semitic rhetoric to underline this view: "The Jew is the enemy and destroyer of the purity of blood, the conscious destroyer of our race ... As socialists, we are opponents of the Jews, because we see, in the Hebrews, the incarnation of capitalism, of the misuse of the nation's goods."[136]

Social class

Nazism rejected the Marxist concept of internationalist class struggle, but supported "class struggle between nations", and sought to resolve internal class struggle in the nation while it identified Germany as a proletarian nation fighting against plutocratic nations.[137]

In 1922, Adolf Hitler discredited other nationalist and racialist political parties as disconnected from the mass populace, especially lower and working-class young people:

The racialists were not capable of drawing the practical conclusions from correct theoretical judgements, especially in the Jewish Question. In this way, the German racialist movement developed a similar pattern to that of the 1880s and 1890s. As in those days, its leadership gradually fell into the hands of highly honourable, but fantastically naïve men of learning, professors, district counsellors, schoolmasters, and lawyers—in short a bourgeois, idealistic, and refined class. It lacked the warm breath of the nation's youthful vigour.[138]

The Nazi Party had many working-class supporters and members, and a strong appeal to the middle class. The financial collapse of the white collar middle-class of the 1920s figures much in their strong support of Nazism.[139] In the poor country that was the Weimar Republic of the early 1930s, the Nazi Party realised their socialist policies with food and shelter for the unemployed and the homeless—later recruited to the Brownshirt Sturmabteilung (SA – Storm Detachment).[139]

Sex and gender

Nazi ideology advocated excluding women from political involvement and confining them to the spheres of "Kinder, Küche, Kirche" (Children, Kitchen, Church).[140] Many women enthusiastically supported the regime but formed their own internal hierarchies.[141]

Hitler's own opinion on the matter of women in Nazi Germany was that while other eras of German history experienced the development and liberation of the female mind, the National Socialist goal was essentially singular in that they wished for them to produce a child.[142] Along this theme, Hitler once remarked of women, "with every child that she brings into the world, she fights her battle for the nation. The man stands up for the Volk, exactly as the woman stands up for the family."[143] Proto-natalist programs in Nazi Germany offered favourable loans and grants to encourage newlyweds with additional incentives for the birth of offspring.[144] Contraception was discouraged for racially valuable women in Nazi Germany and abortion was forbidden through strict legal mandates, including prison sentences for those seeking them and for doctors performing them, whereas abortion for racially "undesirable" persons was encouraged.[145][146]

While unmarried until the very end of the regime, Hitler often made excuses about his busy life hindering any chance for marriage.[147] Among National Socialist ideologues, marriage was valued not from moral considerations but because it provided an optimal breeding environment. Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler reportedly told a confidant that when he established the Lebensborn program, an organisation to dramatically increase the birth rate of "Aryan" children through extramarital relations between women classified as racially pure and their male equals, he had only the purest male "conception assistants" in mind.[148]

Since the Nazis at the beginning of the war extended the Rassenschande (race defilement) law to all foreigners,[109] pamphlets were issued to German women to avoid sexual relations with foreign workers brought to Germany and to view them as a danger to their blood.[149] Although the law was punishable to both genders, German women were targeted more for having sexual relations with foreign forced labourers in Germany.[150] The Nazis issued the Polish decrees on 8 March 1940 which set out regulations concerning the Polish forced labourers (Zivilarbeiter) brought to Germany during World War II. One of the regulations stated that any Pole "who has sexual relations with a German man or woman, or approaches them in any other improper manner, will be punished by death".[151]

After the decrees were enacted, Himmler stated:

Fellow Germans who engage in sexual relations with male or female civil workers of the Polish nationality, commit other immoral acts or engage in love affairs shall be arrested immediately.[152]

The Nazis later issued similar regulations against the Eastern Workers (Ost-Arbeiters), including the death penalty for sexual relations with a German person.[153] Heydrich issued a decree on 20 February 1942 that declared sexual intercourse between a German woman and a Russian worker or prisoner of war would result in the Russian man being punished by the death penalty.[154] A further decree issued by Himmler on 7 December 1942 stated any "unauthorised sexual intercourse" would result in the death penalty.[155] As the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honour did not permit capital punishment for race defilement, special courts were convened to allow the death penalty for some cases.[156] German women accused of race defilement were marched through the streets with her head shaven and a placard around her neck detailing her crime,[157] those convicted were sent to a concentration camp.[149] When Himmler reportedly asked Hitler what the punishment should be for German girls and German women who have been found guilty of race defilement with prisoners of war (POWs) he ordered "every POW who has relations with a German girl or a German would be shot" and the German woman should be publicly humiliated by "having her hair shorn and being sent to a concentration camp".[158]

The League of German Girls was particularly regarded as instructing girls to avoid race defilement, which was treated with particular importance for young females.[159]

Opposition to homosexuality

After the Night of the Long Knives, Hitler promoted Himmler and the SS, who then zealously suppressed homosexuality, saying: "We must exterminate these people root and branch ... the homosexual must be eliminated."[160] In 1936, Himmler established the "Reichszentrale zur Bekämpfung der Homosexualität und Abtreibung" ("Reich Central Office for the Combating of Homosexuality and Abortion").[161] The Nazi régime incarcerated some 100,000 homosexuals during the 1930s.[162] As concentration camp prisoners, homosexual men were forced to wear pink triangle badges.[163][164] Nazi ideology still viewed German gay men as part of the Aryan master race but attempted to force them into sexual and social conformity. Gay men who would not change or feign a change in their sexual orientation were sent to concentration camps under the "Extermination Through Work" campaign.[165]

Religion

The Nazi Party Programme of 1920 guaranteed freedom for all religious denominations not hostile to the State and endorsed Positive Christianity to combat "the Jewish-materialist spirit".[166] It was a modified version of Christianity which emphasised racial purity and nationalism.[167] The Nazis were aided by theologians such as Ernst Bergmann. Bergmann, in his work Die 25 Thesen der Deutschreligion (Twenty-five Points of the German Religion), held that the Old Testament and portions of the New Testament of the Bible were inaccurate. He claimed that Jesus was not a Jew but of Aryan origin, and that Adolf Hitler was the new messiah.[167]

Hitler denounced the Old Testament as "Satan's Bible", and utilising components of the New Testament attempted to demonstrate that Jesus was Aryan and anti-Semitic, such as in John 8:44 where Hitler noted that Jesus is yelling at "the Jews", as well as Jesus saying to the Jews that "your father is the devil", and describing Jesus' whipping of the "Children of the Devil".[168] Hitler claimed that the New Testament included distortions by Paul the Apostle, whom Hitler described as a "mass-murderer turned saint".[168]

The Nazis utilised Protestant Martin Luther in their propaganda. They publicly displayed an original of Luther's On the Jews and their Lies during the annual Nuremberg rallies.[169][170] The Nazis endorsed the pro-Nazi Protestant German Christians organisation.

The Nazis were initially highly hostile to Catholics because most Catholics supported the German Centre Party. Catholics opposed the Nazis' promotion of sterilisation of those deemed inferior, and the Catholic Church forbade its members to vote for the Nazis. In 1933, extensive Nazi violence occurred against Catholics due to their association with the Centre Party and their opposition to the Nazi regime's sterilisation laws.[171] The Nazis demanded that Catholics declare their loyalty to the German state.[172] In propaganda, the Nazis used elements of Germany's Catholic history, in particular the German Catholic Teutonic Knights and their campaigns in Eastern Europe. The Nazis identified them as "sentinels" in the East against "Slavic chaos", though beyond that symbolism the influence of the Teutonic Knights on Nazism was limited.[173] Hitler also admitted that the Nazis' night rallies were inspired by the Catholic rituals he witnessed during his Catholic upbringing.[174] The Nazis did seek official reconciliation with the Catholic Church and endorsed the creation of the pro-Nazi Catholic Kreuz und Adler organisation that supported a national Catholicism.[172] On 20 July 1933, a concordat (Reichskonkordat) was signed between Nazi Germany and the Catholic Church; in exchange for acceptance of the Catholic Church in Germany, it required German Catholics to be loyal to the German state. The Catholic Church then ended its ban on members supporting the Nazi Party.[172]

Historian Michael Burleigh claims that Nazism used Christianity for political purposes, but such use required that "fundamental tenets were stripped out, but the remaining diffuse religious emotionality had its uses".[174] Burleigh claims that Nazism's conception of spirituality was "self-consciously pagan and primitive".[174] However, historian Roger Griffin rejects the claim that Nazism was primarily pagan, noting that although there were some influential neo-paganists in the Nazi Party, such as Heinrich Himmler and Alfred Rosenberg, they represented a minority and their views did not influence Nazi ideology beyond its use for symbolism; it is noted that Hitler denounced Germanic paganism in Mein Kampf and condemned Rosenberg's and Himmler's paganism as "nonsense".[175]

Economics

Generally speaking, Nazi theorists and politicians blamed Germany’s previous economic failures on political causes like the influence of Marxism on the workforce, the sinister and exploitative machinations of what they called international Jewry, and the vindictiveness of the western political leaders' war reparation demands. Instead of traditional economic incentives, the Nazis offered solutions of a political nature, such as the elimination of organised labour groups, rearmament (in contravention of the Versailles Treaty), and biological politics.[176] Various work programs designed to establish full-employment for the German population were instituted once the Nazis seized full national power. Hitler encouraged nationally supported projects like the construction of the Autobahn, the introduction of an affordable people’s car (Volkswagen) and later, the Nazis bolstered the economy through the business and employment generated by military rearmament.[177] Not only did the Nazis benefit early in the regime's existence from the first post-Depression economic upswing, their public works projects, job-procurement program, and subsidised home repair program reduced unemployment by as much as 40 percent in one year, a development which tempered the unfavourable psychological climate caused by the earlier economic crisis and encouraged Germans to march in step with the regime.[178]

To protect the German people and currency from volatile market forces, the Nazis also promised social policies like a national labour service, state-provided health care, guaranteed pensions, and an agrarian settlement program.[179] Agrarian policies were particularly important to the Nazis since they corresponded not just to the economy but to their geopolitical conception of Lebensraum as well. For Hitler, the acquisition of land and soil was requisite in moulding the German economy.[180] To tie farmers to their land, selling agricultural land was prohibited.[181] Farm ownership was nominally private, but business monopoly rights were granted to marketing boards to control production and prices with a quota system.[182]

The Nazis sought to gain support of workers by declaring May Day, a day celebrated by organised labour, to be a paid holiday and held celebrations on 1 May 1933 to honour German workers.[183] The Nazis stressed that Germany must honour its workers.[184] The regime believed that the only way to avoid a repeat of the disaster of 1918 was to secure workers' support for the German government.[183] The Nazis wanted all Germans take part in the May Day celebrations in the hope that this would help break down class hostility between workers and burghers.[184] Songs in praise of labour and workers were played by state radio throughout May Day as well as fireworks and an air show in Berlin.[184] Hitler spoke of workers as patriots who had built Germany's industrial strength, had honourably served in the war and claimed that they had been oppressed under economic liberalism.[185] The Berliner Morgenpost, which had been strongly associated with the political left in the past, praised the regime's May Day celebrations.[185]

The Nazis continued social welfare policies initiated by the governments of the Weimar Republic and mobilised volunteers to assist those impoverished, "racially-worthy" Germans through the National Socialist People's Welfare (NSV) chairman Erich Hilgenfeldt organisation.[186] This organisation oversaw charitable activities, and became the largest civic organisation in Nazi Germany.[186] Successful efforts were made to get middle-class women involved in social work assisting large families.[187] The Winter Relief campaigns acted as a ritual to generate public sympathy.[188] Bonfires were made of school children's differently coloured caps as symbolic of the abolition of class differences.[187] Large celebrations and symbolism were used extensively to encourage those engaged in physical labour on behalf of Germany, with leading National Socialists often praising the "honour of labour", which fostered a sense of community (Gemeinschaft) for the German people and promoted solidarity towards the Nazi cause.[189]

Hitler believed that private ownership was useful in that it encouraged creative competition and technical innovation, but insisted that it had to conform to national interests and be "productive" rather than "parasitical".[190] Private property rights were conditional upon the economic mode of use; if it did not advance Nazi economic goals then the state could nationalise it.[191] Although the Nazis privatised public properties and public services, they also increased economic state control.[192] Under Nazi economics, free competition and self-regulating markets diminished; nevertheless, Hitler's social Darwinist beliefs made him reluctant to entirely disregard business competition and private property as economic engines.[193][194]

Hitler primarily viewed the German economy as an instrument of power. Hitler believed the economy was not just about creating wealth and technical progress so as to improve the quality of life for a nation's citizenry; economic success was paramount in that, it provided the means and material foundations necessary for military conquest.[195] While economic progress generated by National Socialist programs had its role in appeasing the German people, the Nazis and Hitler in particular, did not believe that economic solutions alone were sufficient to thrust Germany onto the stage as a world power. Therefore, the Nazis sought first to secure a command economy through general economic revival accompanied by massive military spending for rearmament, especially later through the implementation of the Four Year Plan, which consolidated their rule and firmly secured a command relationship between the German arms industry and the National Socialist government.[196] Between 1933 and 1939, military expenditures were upwards of 82 billion Reichsmarks and represented 23 percent of Germany's gross national product as the Nazis mobilised their people and economy for war.[197]

Anti-communism

Historians Ian Kershaw and Joachim Fest argue that in post-World War I Germany, the Nazis were one of many nationalist and fascist political parties contending for the leadership of Germany's anti-communist movement. The Nazis claimed that communism was dangerous to the well-being of nations because of its intention to dissolve private property, its support of class conflict, its aggression against the middle class, its hostility towards small business, and its atheism.[198] Nazism rejected class conflict-based socialism and economic egalitarianism, favouring instead a stratified economy with social classes based on merit and talent, retaining private property, and the creation of national solidarity that transcends class distinction.[199]

During the 1920s, Hitler urged disparate Nazi factions to unite in opposition to Jewish Bolshevism.[200] Hitler asserted that the "three vices" of "Jewish Marxism" were democracy, pacifism, and internationalism.[201]

In 1930, Hitler said: "Our adopted term 'Socialist' has nothing to do with Marxist Socialism. Marxism is anti-property; true Socialism is not."[202] In 1942, Hitler privately said: "I absolutely insist on protecting private property ... we must encourage private initiative".[203]

During the late 1930s and the 1940s, anti-communist regimes and groups that supported Nazism included the Falange in Spain; the Vichy regime and the 33rd Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS Charlemagne (1st French) in France; and in Britain the Cliveden Set, Lord Halifax, the British Union of Fascists under Sir Oswald Mosley, and associates of Neville Chamberlain.[204]

Anti-capitalism

The Nazis argued that capitalism damages nations due to international finance, the economic dominance of big business, and Jewish influences.[198] Nazi propaganda posters in working class districts emphasised anti-capitalism, such as one that said: "The maintenance of a rotten industrial system has nothing to do with nationalism. I can love Germany and hate capitalism."[205]

Adolf Hitler, both in public and in private, expressed disdain for capitalism, arguing that it holds nations ransom in the interests of a parasitic cosmopolitan rentier class.[206] He opposed free market capitalism's profit-seeking impulses and desired an economy in which community interests would be upheld.[190]

Hitler distrusted capitalism for being unreliable due to its egotism, and he preferred a state-directed economy that is subordinated to the interests of the Volk.[206]

Hitler told a party leader in 1934, "The economic system of our day is the creation of the Jews."[206] Hitler said to Benito Mussolini that capitalism had "run its course".[206] Hitler also said that the business bourgeoisie "know nothing except their profit. 'Fatherland' is only a word for them."[207] Hitler was personally disgusted with the ruling bourgeois elites of Germany during the period of the Weimar Republic, who he referred to as "cowardly shits".[208]

In Mein Kampf, Hitler effectively supported mercantilism, in the belief that economic resources from their respective territories should be seized by force; he believed that the policy of Lebensraum would provide Germany with such economically valuable territories.[209] He argued that the only means to maintain economic security was to have direct control over resources rather than being forced to rely on world trade.[209] He claimed that war to gain such resources was the only means to surpass the failing capitalist economic system.[209]

A number of other Nazis held strong revolutionary socialist and anti-capitalist beliefs, most prominently Ernst Röhm, the leader of the Sturmabteilung (SA).[210] Röhm claimed that the Nazis' rise to power constituted a national revolution, but insisted that a socialist "second revolution" was required for Nazi ideology to be fulfilled.[30] Röhm's SA began attacks against individuals deemed to be associated with conservative reaction.[30] Hitler saw Röhm's independent actions as violating and possibly threatening his leadership, as well as jeopardising the regime by alienating the conservative President Paul von Hindenburg and the conservative-oriented German Army.[31] This resulted in Hitler purging Röhm and other radical members of the SA.[31]

Another radical Nazi, Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, had stressed the socialist character of Nazism, and claimed in his diary in the 1920s that if he were to pick between Bolshevism and capitalism, he said "in final analysis", "it would be better for us to go down with Bolshevism than live in eternal slavery under capitalism".[211]

Totalitarianism

Under Nazism, with its emphasis on the nation, individual needs were subordinate to those of the wider community.[212] Hitler declared that "every activity and every need of every individual will be regulated by the collectivity represented by the party" and that "there are no longer any free realms in which the individual belongs to himself".[213] Himmler justified the establishment of a repressive police state, in which the security forces could exercise power arbitrarily, by claiming that national security and order should take precedence over the needs of the individual.[214]

According to the famous philosopher and political theorist, Hannah Arendt, the allure of Nazism as a totalitarian ideology (with its attendant mobilisation of the German population) resided within the construct of helping that society deal with the cognitive dissonance resultant from the tragic interruption of the First World War and the economic and material suffering consequent to the Depression, and brought to order the revolutionary unrest occurring all around them. Instead of the plurality that existed in democratic or parliamentary states, Nazism as a totalitarian system promulgated "clear" solutions to the historical problems faced by Germany, levied support by de-legitimizing the former government of Weimar, and provided a politico-biological pathway to a better future, one free from the uncertainty of the past. It was the atomised and disaffected masses that Hitler and the party elite pointed in a particular direction, and using clever propaganda to make them into ideological adherents, exploited in bringing Nazism to life.[215]

While the ideologues of Nazism, much like those of Stalinism, abhorred democratic or parliamentary governance as practiced in the U.S. or Britain, their differences are substantial. An epistemic crisis occurs when one tries to synthesize and contrast Nazism and Stalinism as two-sides of the same coin with their similarly tyrannical leaders, state-controlled economies, and repressive police structures; namely, while they share a common thematic political construction, they are entirely inimical to one another in their worldviews and when more carefully analysed against one another on a one-to-one level, an "irreconcilable asymmetry" results.[216]

Post-war Nazism

Following Nazi Germany's defeat in World War II and the end of the Holocaust, overt expressions of support for Nazi ideas were prohibited in Germany and other European countries. Nonetheless, movements that self-identify as National Socialist or are described as adhering to National Socialism continue to exist on the fringes of politics in many western societies. Usually espousing a white supremacist ideology, many deliberately adopt the symbols of Nazi Germany.[217]

See also

- Consequences of German Nazism

- Functionalism versus intentionalism

- List of books about Nazi Germany

- Nazi occultism

- Political views of Adolf Hitler

References

Notes

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2003) [1917]. Roach, Peter; Hartmann, James; Setter, Jane (eds.). English Pronouncing Dictionary. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 3-12-539683-2.

- ^ a b c Baum, Bruce David (2006). The Rise and Fall of the Caucasian Race: A Political History of Racial Identity. New York City / London: New York University Press. p. 156.

- ^ Kobrak, Christopher; Hansen, Per H.; Kopper, Christopher (2004). "Business, Political Risk, and Historians in the Twentieth Century". In Kobrak, Christopher; Hansen, Per H. (eds.). European Business, Dictatorship, and Political Risk, 1920-1945. New York City / Oxford: Berghahn Books. pp. 16–7. ISBN 1-57181-629-1.

- ^ Lepage, Jean-Denis (2009). Hitler Youth, 1922-1945: An Illustrated History. McFarland. p. 9. ISBN 978-0786439355.

- ^ Gottlieb, Henrik; Morgensen, Jens Erik, eds. (2007). Dictionary Visions, Research and Practice: Selected Papers from the 12th International Symposium on Lexicography, Copenhagen 2004 (illustrated ed.). Amsterdam: J. Benjamins Pub. Co. p. 247. ISBN 978-9027223340. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ^ a b Harper, Douglas. "Nazi". etymonline.com. Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ^ a b c Rabinbach, Anson; Gilman, Sander, eds. (2013). The Third Reich Sourcebook. Berkeley, Calif.: California University Press. p. 4. ISBN 9780520955141.

- ^ a b Copping, Jasper (23 October 2011). "Why Hitler hated being called a Nazi and what's really in humble pie – origins of words and phrases revealed". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ^ Seebold, Elmar, ed. (2002). Kluge Etymologisches Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache (in German) (24th ed.). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-017473-1.

- ^ "Naziism". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ Fritzsche, Peter (1998). Germans into Nazis. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674350922.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Eatwell, Roger (1997). Fascism, A History. Viking-Penguin. pp. xvii–xxiv, 21, 26–31, 114–40, 352. ISBN 978-0140257007.

Griffin, Roger (2000). "Revolution from the Right: Fascism". In Parker, David (ed.). Revolutions and the Revolutionary Tradition in the West 1560-1991. London: Routledge. pp. 185–201. ISBN 978-0415172950. - ^ Oliver H. Woshinsky. Explaining Politics: Culture, Institutions, and Political Behavior. Oxon, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2008. p. 156.

- ^ Hitler, Adolf in Domarus, Max and Patrick Romane, eds. The Essential Hitler: Speeches and Commentary, Waulconda, Illinois: Bolchazi-Carducci Publishers, Inc., 2007, p. 170.

- ^ Koshar, Rudy. Social Life, Local Politics, and Nazism: Marburg, 1880-1935, University of North Carolina Press, 1986. p. 190.

- ^ Hitler, Adolf, Mein Kampf, Bottom of the Hill Publishing, 2010. p. 287.

- ^ Adolf Hitler, Max Domarus. The Essential Hitler: Speeches and Commentary. pp. 171, 172–173.

- ^ a b Peukert, Detlev, The Weimar Republic. 1st paperback ed. Macmillan, 1993. ISBN 9780809015566, pp. 73–74.

- ^ a b Peukert, Detlev, The Weimar Republic. 1st paperback ed. Macmillan, 1993. ISBN 9780809015566, p. 74.

- ^ a b Beck, Hermann The Fateful Alliance: German Conservatives and Nazis in 1933: The Machtergreifung in a New Light, Berghahn Books, 2008. ISBN 9781845456801, p. 72.

- ^ Beck, Hermann The Fateful Alliance: German Conservatives and Nazis in 1933: The Machtergreifung in a New Light, 2008. pp. 72–75.

- ^ Beck, Hermann The Fateful Alliance: German Conservatives and Nazis in 1933: The Machtergreifung in a New Light, 2008. p. 84.

- ^ Miranda Carter. George, Nicholas and Wilhelm: Three Royal Cousins and the Road to World War I. Borzoi Book, 2009. Pp. 420.

- ^ a b c d Mann, Michael, Fascists, New York City: Cambridge University Press, 2004. p. 183.

- ^ Browder, George C., Foundations of the Nazi Police State: The Formation of Sipo and SD, paperback, Lexington, Kentucky, USA: Kentucky University Press, 2004. p. 202.

- ^ a b c Bendersky, Joseph W. (2007). A Concise History of Nazi Germany. Plymouth, England: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc. p. 96. ISBN 9780742553637.

- ^ Glenn D. Walters. Lifestyle Theory: Past, Present, and Future. Nova Publishers, 2006. p. 40.

- ^ a b Weber, Thomas, Hitler's First War: Adolf Hitler, the Men of the List Regiment, and the First World War, Oxford, England, UK: Oxford University Press, 2011. p. 251.

- ^ a b Gaab, Jeffrey S., Munich: Hofbräuhaus & History: Beer, Culture, & Politics, 2nd ed. New York City: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc, 2008. p. 61.

- ^ Overy, R.J., The Dictators: Hitler's Germany and Stalin's Russia, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2004. pp. 399–403.

- ^ a b c Nyomarkay, Joseph (1967). Charisma and Factionalism in the Nazi Party. Univ Of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0816604296.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) P. 130. - ^ a b c d Nyomarkay 1967, p. 133.

- ^ a b Furet, François, Passing of an Illusion: The Idea of Communism in the Twentieth Century, Chicago, Illinois' London, England: University of Chicago Press, 1999. ISBN 0-226-27340-7, pp. 191–192.

- ^ Furet, François, Passing of an Illusion: The Idea of Communism in the Twentieth Century, 1999. p. 191.

- ^ Ryback, Timothy W. (2010). Hitler's Private Library: The Books That Shaped His Life. New York City; Toronto: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0307455260.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) Pp. 129–130. - ^ a b c d Ryback 2010, p. 129.

- ^ George L. Mosse, The Crisis of German Ideology: Intellectual Origins of the Third Reich (New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1964), pp. 19-23.

- ^ Thomas Lekan and Thomas Zeller, "Introduction: The Landscape of German Environmental History," in Germany's Nature: Cultural Landscapes and Environmental History, edited by Thomas Lekan and Thomas Zeller (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2005), p. 3.

- ^ The Nazi concept Lebensraum has connections to this idea with German farmers rooted to their soil, needing more of it for the expansion of the German Volk - whereas the Jew is precisely the opposite, nomadic and urban by nature. See: Roderick Stackelberg, The Routledge Companion to Nazi Germany (New York: Routledge, 2007), p. 259.

- ^ Additional evidence of Riehl’s legacy can be seen in the Riehl Prize, Die Volkskunde als Wissenschaft (Folklore as Science) which was being awarded in 1935 by the Nazis. See: George L. Mosse, The Crisis of German Ideology: Intellectual Origins of the Third Reich (New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1964), p. 23. Applicants for the Riehl prize had stipulations that included only being of Aryan blood, and no evidence of membership in any Marxist parties or any organisation that stood against National Socialism. See: Hermann Stroback, "Folklore and Fascism before and around 1933," in The Nazification of an Academic Discipline: Folklore in the Third Reich, edited by James R Dow and Hannjost Lixfeld (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994), pp. 62-63.

- ^ Cyprian Blamires. World Fascism: A Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1. Santa Barbara, California, USA: ABC-CLIO, Inc., 2006. p. 542.

- ^ Keith H. Pickus. Constructing Modern Identities: Jewish University Students in Germany, 1815–1914. Detroit, Michigan, USA: Wayne State University Press, 1999. p. 86.

- ^ a b Jonathan Olsen. Nature and Nationalism: Right-wing Ecology and the Politics of Identity in Contemporary Germany. New York, New York, USA: Palgrave Macmillan, 1999. p. 62.

- ^ a b Nina Witoszek, Lars Trägårdh. Culture and Crisis: The Case of Germany and Sweden. Berghahn Books, 2002. pp. 89–90.

- ^ Witoszek, Nina and Lars Trägårdh, Culture and Crisis: The Case of Germany and Sweden, Berghahn Books, 2002, p. 90.