Sully Historic Site: Difference between revisions

found it in sandbox editing, citations just needed |ref=harv}} |

accidently included {{userspace draft}} |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{userspace draft}} |

|||

{{Infobox NRHP |

{{Infobox NRHP |

||

| name = Sully |

| name = Sully |

||

Revision as of 22:02, 11 November 2015

Sully | |

Sully Main House | |

| Location | North of the junction of VA 28 and US 50, near Chantilly, Virginia |

|---|---|

| Area | 65 acres (26 ha) |

| Built | 1794 |

| NRHP reference No. | 70000793[1] |

| VLR No. | 029-0037 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | December 18, 1970 |

| Designated VLR | October 6, 1970 [2] |

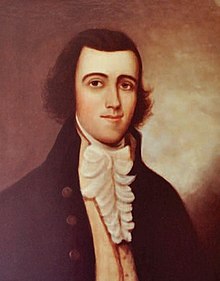

Sully Historic Site, more commonly known as Sully Plantation, is a historic plantation site in Chantilly, Virginia.[2] Richard Bland Lee, Northern Virginia's first Representative[3] to Congress, brother[3] of Henry 'Light Horse Harry' Lee III and Charles Lee, and uncle[3] to Robert E. Lee built the main house[2] in 1794.

The land including the main house was acquired by the Federal Government in 1958 to make way for construction of Dulles Airport. A campaign to save the site began almost immediately afterwards. Those involved included previous owners of the property, Lee descendants, and a neighbor, Eddie Wagstaff, who later endowed the Sully Foundation that still provides support for the site. This campaign finally paid off in 1959 when Congress passed, and President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed, legislation saving Sully.[4]

The Fairfax County Park Authority agreed to operate the site as a county historical park, and has since acquired an additional 60 acres to bring the total size of Sully Historic Site to approximately 120 acres.[5] The site's historic period of significance encompasses the ownership of Richard Bland Lee and Francis Lighfoot Lee (1787–1838). Interpretation at the site and most of its displays reflect the ownership of its founder, Richard Bland Lee.[6]

History

Pre-Lee Period

The land that would become part of Sully was likely controlled by several groups before the Doeg claimed the area. English settlers encountered Algonquian language speaking members of the Doeg tribe in modern day Northern Virginia.[7] The Doeg are most well known for their raid in July of 1675 that became a part of Bacon's Rebellion.[8] English colonists settling in modern Northern Virginia came into conflict with the Doeg from 1661 to 1664.[9] When diplomatic attempts failed, the governor sent the Rappahannock County militia in June of 1666.[9] The specifics of that military action are unclear, but later land grants to English settlers are not disputed, suggesting the English gained control of the area. The English presumptively took control after a violent conflict with the Doeg in 1666. Nothing is recorded about the disposition of this land from the time when the English gained control of it until the land is patented by the Lee family of Virginia.

Lee Period

Richard Bland Lee

Sully is located on a portion of the 3,111 acres (1,259 ha) of land situated between Cub Run and Flatlick Run in what is now Fairfax County, Virginia. Originally acquired in 1725 by Richard Bland Lee's grandfather, Henry Lee I, it was inherited by Richard's father Henry Lee II of "Leesylvania".[10] At his death in 1787, the land was divided between Richard and his younger brother Theodorick Lee.[10] Being the older of the two, Richard was given the more alluvial northern half, having resided there as manager of the property since approximately 1781. During this period, tobacco was the primary cash crop grown at what would later be called Sully.

Upon taking ownership of the land in his own right, Richard eliminated or severely curtailed tobacco production in favor of more sustainable crops, including wheat, corn, rye, and barley. This helped halt the depletion of the soil, which is characteristic of tobacco production, and allowed him to practice crop rotation and nutrient replenishment of his fields, keeping them all in production. He also planted fruit orchards, including peach and apple trees, which he used to produce spirits. In 1801, he constructed a dairy and began limited production of dairy goods, primarily under the supervision of his wife Elizabeth Collins Lee.

After his election to Congress in 1789, and for most of the next five years, Richard turned day-to-day management of his estate over to his brother Theodorick, who supervised spring planting and fall harvest.[11] Theodorick also managed the collection of rent from tenant farmers and the construction of the large house Richard had planned for the estate, on which construction had begun in 1794. Before he left for Congress in 1789, Richard had chosen the name "Sully" for his estate. The exact origin of the name is unknown, though Robert S. Gamble, in Sully: Biography of a House, speculates that Sully was named after "Château de Sully" in the valley of Loire in France. According to Gamble, "If he turned to a specific source, it was doubtless the Memoires of Maximilien de Bethune, Duke of Sully and France's Minister of Finance under Henry IV." This work was well known among wealthy Virginians in the late 18th century.[12]

By 1811, having been drawn into heavy debt trying to aid his brothers, Henry Lee III and Charles Lee, extricate themselves from severe financial difficulties, Richard Bland Lee decided he could no longer sustain ownership of Sully. Accordingly, he decided to sell the plantation to raise cash to pay some of the debt. He sold Sully for $18,000 to his second cousin, Francis Lightfoot Lee II, son of Richard Henry Lee, author of the Lee Resolution (Resolution on Independence) and signer of the Declaration of Independence.

Francis LightFoot Lee II

Francis Lightfoot Lee II was a man who it seemed fate would always work against. The beneficiary of a stellar education at Phillips Academy and the College of New Jersey (now Princeton), as well as a scion of one of the most prominent families in America, Lee was never able to live up to the promise his education and pedigree foreshadowed.[12] After a series of disappointments, including the death of his first wife, Elizabeth Fitzgerald in 1808, two opportunities presented themselves that promised to improve Lee's prospects. First, he was again married in 1810, this time to Jane Fitzgerald (sister to his first wife), who bore him five children, and second, a particularly attractive piece of property, the estate of his second cousin Richard Bland Lee, was put up for sale. Lee purchased the property in 1811, hoping to prove himself a successful and progressive planter.

For several years after his purchase of Sully, Francis Lightfoot Lee seemed to live up to his own expectations. Applying the latest methods for raising yields and keeping fields fertile, Lee was able to realize an annual profit of $1,500 to $2,500.[13] As he gained a reputation for a "judicious system of husbandry,"[12] Lee's reputation as a successful planter had escaped the confines of Sully Plantation itself. In addition to success as a planter, Francis' private life was flourishing as well. Between 1811 and 1815, he and his wife welcomed four children to their family, including Samuel Phillips Lee, named for the founder of Phillips Academy,[12] and later an Admiral in the Navy and one of the only members of the Lee family to fight for the Union in the Civil War. But, as it seemed to always be the case for Lee, fate would intervene to deal him another set of disappointments.

In 1816, as the result of giving birth to their fifth child Frances Ann Lee, his second wife, Jane Fitzgerald Lee, died. This initiated a slow decline in the health of both Francis Lightfoot Lee himself, as well as Sully. Lee seemed to slowly lose interest in the farming operations at Sully. Finally, in 1820 Lee had either a nervous breakdown, or possibly a stroke. In either case, he became unable to care for himself and in 1825 was committed to the Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia.[12]

Following this breakdown, Sully was placed under the administrative care of Lee's nephew Richard Henry Lee II, a move which did not turn out well. Richard Henry Lee II's management was marked by negligence and apparent apathy towards the dishonesty of managers who were embezzling money from the estate. As noted in a later suit filed against administrator Lee, he had allowed an estate "clear of debt, well stocked, well arranged under a good system as it had been for years" to be wasted and to sink into increasing debt. Richard Henry Lee II was replaced as administrator by Colonel W.C.B. Butler on January 1, 1827 who "also proved unsatisfactory,"[12] and then by Colonel George Washington Hunter in 1830. As Robert Gamble notes however, "in no hands...would Sully fare as well as when it had been assiduously maintained by a single, devoted, industrious proprietor."[12]

After their father's move to the Pennsylvania Hospital during the summer of 1825, Francis Lightfoot Lee's children (with the exception of Samuel Philips Lee who had entered the Navy), were under the care of William and Winifred Brent. The Brents were relatives who had moved to Sully to care for the Lee children and to start at Sully, a "select seminary" [12] for boys and girls. William Brent, in addition to being related to the Lee's, was also the nephew of the Richard Brent who had defeated Ricard Bland Lee in the congressional election of 1794. William Brent had also served in the Virginia House of Delegates from 1810-1811, and would later be appointed Chargé d'affaires to Buenos Aires, Argentina from 1844 to 1846.[14]

During subsequent years, as the Lee children grew older they began to leave Sully. Samuel Phillps Lee had entered the Navy, and John Lee went to West Point. Arthur Lee moved west to the Ohio country, while his oldest daughter Jane Elizabeth Lee married Henry Tazewell Harrison in a sunrise ceremony at Sully on February 6, 1834. With his brothers-in-law absent from the estate, Harrison took over representing their interests with the appointed administrator, Colonel Hunter, whom he replaced on July 18, 1836.[12] It was decided, in order to prevent further deterioration of the property and to keep it from becoming a liability to the Lee family, Sully needed to be sold. Finally, in 1838, after a bizarre period, in which the estate had ostensibly been sold to a buyer who was arrested in England prior to completing the purchase, Sully was sold to merchant and speculator William Swartout.[12]

Post-Lee Period

Chain of Ownership

1725-1747 Henry Lee I

1747-1787 Henry Lee II

1787-1811 Richard Bland Lee

1811-1838 Francis Lightfoot Lee II purchased the estate from his second cousin.[12]

1838-1842 William Swartwort, Speculator

1842-1852 Jacob Haight introduced innovative scientific farming techniques.

1852-1869 James Barlow

1869-1874 Stephen Shear

1874-1910 Conrad Shear

1910-1919 William Miller, Real Estate Agent

1919-1939 King Poston converted Sully to a dairy farm.

1939-1946 Walter Thurston, who was United States ambassador to Mexico (1946-1950).

1946-1958 Frederick Nolting, who was United States ambassador to South Vietnam (1961-1962).

1958–Present Federal Aviation Administration

1959–Present Fairfax County Park Authority

Gallery

-

'Sully Main House (built 1794)

-

Pen used by President Eisenhower to sign the bill saving Sully (1959)

Notes

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ a b c Langan 2015; [[#CITEREF|]].

- ^ a b c Salmon & Peters 1994.

- ^ Peck 2005; [[#CITEREF|]].

- ^ Kane 2005; Page 2007.

- ^ Kane 2005.

- ^ McCary 2009.

- ^ Heinemann 2007.

- ^ a b Rountree 1996.

- ^ a b Templeman 1973.

- ^ Eckenrode 1910; Marcus & Perry 1992.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Gamble 1993.

- ^ Netherton 1978.

- ^ Brent 1946.

References

- Brent, Chester Horton (1946). Descendants of Col. Giles Brent, Capt George Brent and Robert Brent, Gentlemen. Priv. print. by the Tuttle Pub. Co.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Eckenrode, H. J. (1910). Separation of Church and State in Virginia: A Study in the Development of the Revolution. Richmond: Virginia State Library.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gamble, Robert S. (1973). Sully: The Biography of a House. Sully Foundation.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Heinemann, R. L. (2007). Old Dominion, New Commonwealth: A History of Virginia, 1607-2007. University of Virginia Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kane, Michael A. (2005-07-27). Sully Historic Site Master Plan. Fairfax, VA: Fairfax County Park Authority.

{{cite conference}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Langan, Julie (2015-10-02). "Virginia Landmarks Register". Virginia Department of Historic Resources.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Marcus, M; Perry, J. R. (1992). The Documentary History of the Supreme Court of the United States, 1789-1800: Organizing the Federal Judiciary : Legislation and Commentaries. New York: Columbia University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McCary (2009). Indians in Seventeenth-Century Virginia. Clearfield.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Netherton, Nan (1978-01-01). Fairfax County, Virginia: A History. Fairfax County Board of Supervisors. ISBN 978-0-9601630-1-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Page, Terry J. (2007-06-07). Replacement Access for Sully Historic Site and the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority's Southern Parcel. Federal Aviation Administration.

{{cite conference}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Page, T. N. (1912). Robert E. Lee, Man and Soldier. Scribner.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Prats, J. J. (March 31, 2006). "Sully Plantation". The Historical Marker Database.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Peck, Margaret C. (2005). Washington Dulles International Airport. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-1847-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rountree, H. C. (1996). Pocahontas's People: the Powhatan Indians of Virginia Through Four Centuries. University of Oklahoma Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Salmon, J; Peters, M (1994). A Guidebook to Virginia's Historical Markers. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Templeman, E (1973). Virginia Homes of the Lees. Annandale, VA: Charles Baptie Studios.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)