American urban history: Difference between revisions

→Colonial era and American Revolution: Small fix |

→top: Anti-urbanism |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''American urban history''' is the study of cities of the United States. Local historians have always written about their own cities. Starting in the 1920s, and led by [[Arthur Schlesinger, Sr.]] at Harvard, professional historians began comparative analysis of what cities have in common, and started using theoretical models and scholarly biographies of specific cities.<ref>Michael Frisch, "American urban history as an example of recent historiography." ''History and Theory'' (1979): 350-377. [http://www.jstor.org/stable/2504535 in JSTOR]</ref> |

'''American urban history''' is the study of cities of the United States. Local historians have always written about their own cities. Starting in the 1920s, and led by [[Arthur Schlesinger, Sr.]] at Harvard, professional historians began comparative analysis of what cities have in common, and started using theoretical models and scholarly biographies of specific cities.<ref>Michael Frisch, "American urban history as an example of recent historiography." ''History and Theory'' (1979): 350-377. [http://www.jstor.org/stable/2504535 in JSTOR]</ref> The United States has also had a long history of hostility to the city, as characterized for example by Thomas Jefferson's [[History of agrarianism|agrarianism]]. <ref>Steven Conn, ''Americans Against the City: Anti-Urbanism in the Twentieth Century'' (2014)</ref> |

||

==Historiography== |

==Historiography== |

||

Revision as of 08:24, 8 April 2015

American urban history is the study of cities of the United States. Local historians have always written about their own cities. Starting in the 1920s, and led by Arthur Schlesinger, Sr. at Harvard, professional historians began comparative analysis of what cities have in common, and started using theoretical models and scholarly biographies of specific cities.[1] The United States has also had a long history of hostility to the city, as characterized for example by Thomas Jefferson's agrarianism. [2]

Historiography

American urban history is a branch of the broader field of Urban history. That field of history examines the historical development of cities and towns, and the process of urbanization. The approach is often multidisciplinary, crossing boundaries into fields like social history, architectural history, urban sociology, urban geography business history, and even archaeology. Urbanization and industrialization were popular themes for 20th-century historians, often tied to an implicit model of modernization, or the transformation of rural traditional societies.

In the United States from the 1920s to the 1990s many of the most influential monographs began as one of the 140 PhD dissertations at Harvard University directed by Arthur Schlesinger, Sr. (1888–1965) or Oscar Handlin (1915–2011).[3] The field grew rapidly after 1970, leading one prominent scholar, Stephan Thernstrom, to note that urban history apparently deals with cities, or with city-dwellers, or with events that transpired in cities, with attitudes toward cities – which makes one wonder what is not urban history.[4]

Colonial era and American Revolution

Historian Carl Bridenbaugh examined in depth five key cities: Boston (population 16,000 in 1760), Newport Rhode Island (population 7500), New York City (population 18,000), Philadelphia (population 23,000), and Charles Town (Charlestown, South Carolina), (population 8000). He argues they grew from small villages to take major leadership roles in promoting trade, land speculation, immigration, and prosperity, and in disseminating the ideas of the Enlightenment, and new methods in medicine and technology. Furthermore, they sponsored a consumer taste for English amenities, developed a distinctly American educational system, and began systems for care of people meeting welfare. The cities were not remarkable by European standards, but they did display certain distinctly American characteristics, according to Bridenbaugh. There was no aristocracy or established church, there was no long tradition of powerful guilds. The colonial governments were much less powerful and intrusive and corresponding national governments in Europe. They experimented with new methods to raise revenue, build infrastructure and to solve urban problems.[5] They were more democratic than European cities, in that a large fraction of the men could vote, and class lines were more fluid. Contrasted to Europe, printers (especially as newspaper editors) had a much larger role in shaping public opinion, and lawyers moved easily back and forth between politics and their profession. Bridenbaugh argues that by the mid-18th century, the middle-class businessmen, professionals, and skilled artisans dominated the cities. He characterizes them as "sensible, shrewd, frugal, ostentatiously moral, generally honest," public spirited, and upwardly mobile, and argues their economic strivings led to "democratic yearnings" for political power.[6][7]

Colonial powers established villages of a few hundred population as administrative centers, providing a governmental presence, as well has trading opportunities, and some transportation facilities. Representative examples include Spanish towns of Santa Fe, New Mexico, San Antonio, Texas, and Los Angeles, California, French towns of New Orleans, Louisiana and Detroit, Michigan; Dutch towns of New Amsterdam (New York City), and the Russian town of New Archangel (now Sitka). When their territory was absorbed into the United States, these towns expanded their administrative roles.[8] Numerous historians have explored the roles of working-class men, including slaves, in the economy of the colonial cities,[9] and in the early Republic.[10]

There were few cities in the entire South, and Charleston (Charles Town) and New Orleans were the most important before the Civil War. The colony of South Carolina was settled mainly by planters from the overpopulated sugar island colony of Barbados, who brought large numbers of African slaves from that island.[11] As Charleston grew as a port for the shipment of rice and later cotton, so did the community's cultural and social opportunities. The city had a large base of elite merchants and rich planters. The first theater building in America was built in Charleston in 1736, but was later replaced by the 19th-century Planter's Hotel where wealthy planters stayed during Charleston's horse-racing season (now the Dock Street Theatre, known as one of the oldest active theaters built for stage performance in the United States. Benevolent societies were formed by several different ethnic groups: the South Carolina Society, founded by French Huguenots in 1737; the German Friendly Society, founded in 1766; and the Hibernian Society, founded by Irish immigrants in 1801. The Charleston Library Society was established in 1748 by some wealthy Charlestonians who wished to keep up with the scientific and philosophical issues of the day. This group also helped establish the College of Charleston in 1770, the oldest college in South Carolina, the oldest municipal college in the United States, and the 13th oldest college in the United States.[12]

By the 1775 the largest city was Philadelphia at 40,000, followed by New York (25,000), Boston (16,000), Charleston (12,000), and Newport (11,000), along with Baltimore, Norfolk, and Providence, with 6000, 6000, and 4400 population. They too were all seaports and on any one day each hosted a large transient population of Sailors and visiting businessmen. On the eve of the Revolution, 95 percent of the American population lived outside the cities--much to the frustration of the British, who were able to capture the cities with their Royal Navy, but lacked the manpower to occupy and subdue the countryside. In explaining the importance of the cities in shaping the American Revolution, Benjamin Carp compares the important role of waterfront workers, taverns, churches, kinship networks, and local politics.[13] Historian Gary B. Nash emphasizes the role of the working class, and their distrust of their betters, in northern ports. He argues that working class artisans and skilled craftsmen made up a radical element in Philadelphia that took control of the city starting about 1770 and promoted a radical Democratic form of government during the revolution. They held power for a while, and used their control of the local militia disseminate their ideology to the working class and to stay in power until the businessmen staged a conservative counterrevolution.[14]

The new nation, 1783-1815

The cities played a major role in fomenting the American Revolution, but they were hard hit during the war itself, 1775-83. They lost their main role as oceanic ports, because of the blockade by the British Navy. Furthermore the British occupied the cities, especially New York 1776-83, as well as Boston, Philadelphia and Charleston for briefer periods. During the occupations cities were cut off from their hinterland trade and from overland communication. The British finally departed in 1783, they took out large numbers of wealthy merchants, resume their business activities elsewhere in the British Empire. The older cities finally restored their economic basis; growing cities included Salem, Massachusetts, (which opened a new trade with China), New London, Connecticut, and especially Baltimore, Maryland. The Washington administration under the leadership of Secretary of the treasury Alexander Hamilton set up a national bank in 1791, and local banks began to flourish in all the cities. Merchant entrepreneurship flourished and was a powerful engine of prosperity in the cities.[15] Merchants and financiers of the cities were especially sensitive to the weakness of the old Confederation system; when it came time to ratify the much stronger new Constitution in 1788, all the nation's cities, North and South, voted in favor, while the rural districts were divided. [16]

The national capital was at Philadelphia until 1800, when it was moved to Washington. Apart from the murderous Yellow Fever epidemic of 1793, which killed about 10 percent of the population, Philadelphia had a marvelous reputation as the "cleanest, best-governed, healthiest, and most elegant of American cities." Washington, built in a fever-ridden swamp with long hot miserable summers, was ranked far behind Philadelphia, although it did escape Yellow Fever.[17]

World peace only lasted a decade, for in 1793 a two-decade-long war between Britain and France and their allies broke out. As the leading neutral trading partner the United States did business with both sides. France resented it, and the Quasi-War of 1798-99 disrupted trade. Outraged at British impositions on American merchant ships, and sailors, the Jefferson and Madison administrations engaged in economic warfare with Britain 1807-1812, and then full-scale warfare 1812 to 1815. The result was additional serious damage to the mercantile interests.[18][19]

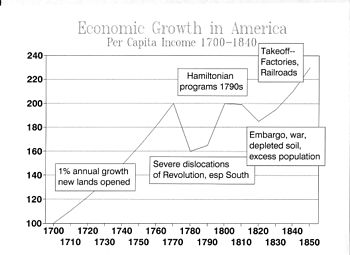

Not all was gloomy in urban history, however. Although there was relatively little immigration from Europe, the rapid expansion of settlements to the West, and the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, open up vast frontier lands. New Orleans and St. Louis joined the United States, and entirely new cities were opened in Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Nashville and points west. Historian Richard Wade has emphasized the importance of the new cities in the Westward expansion in settlement of the farmlands. They were the transportation centers, and nodes for migration and financing of the westward expansion. The newly opened regions had few roads, but a very good river system in which everything flowed downstream to New Orleans. With the coming of the steamboat after 1820, it became possible to move merchandise imported from the Northeast and from Europe upstream to new settlements. The opening of the Erie Canal made Buffalo the jumping off point for the lake transportation system that made important cities out of Cleveland, Detroit, and especially Chicago.[20]

The first stage of rapid urban growth, 1815-1860

| Population of the city | Boston and its suburbs | New York | Philadelphia |

| 1820 | 63,000 | 152,000 | 137,000 |

| 1840 | 124,000 | 391,000 | 258,000 |

| 1860 | 289,000 | 1,175,000 | 566,000 |

| source [21] |

New York, with a population of 96,000 in 1810 surged far beyond its rivals, reaching a population of 1,080,000 in 1860, compared to 566,000 in Philadelphia, 212,000 in Baltimore, 178,000 in Boston (289,000 including the Boston suburbs), and 169,000 in New Orleans.[22] Historian Robert Albion identifies four aggressive moves by New York entrepreneurs and politicians that helped it jump to the top of American cities. It set up an auction system that efficiently and rapidly sold imported cargoes; it organized a regular transatlantic packet service to England; it built a large-scale coastwise trade, especially one that brought Southern cotton to New York for reexport to Europe; it sponsored the Erie Canal, which opened a large new market in upstate New York and the Old Northwest. [23] The main rivals, Boston Philadelphia and Baltimore, tried to compete with the Erie Canal by opening their own networks of canals and railroads; they never caught up.[24] The opening of the Erie Canal made Buffalo the jumping off point for the lake transportation system that made important cities out of Cleveland, Detroit, and especially Chicago.[25] Manufacturing was not a major factor in the growth of the largest cities at this point. Instead factories were chiefly being built in towns and smaller cities, especially in New England, having waterfalls or fast rivers that were harnessed to generate the power, or were closer to coal supplies, as in Pennsylvania.

National leadership

America's Financial, business and cultural leadership (that is, literature, the arts, and the media) were concentrated in the three or four largest cities. Political leadership was never concentrated there. It was divided between Washington and the state capitals, and many states deliberately moved their state capital out of their largest city, including New York, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Illinois, Missouri, South Carolina , Louisiana, Texas and California. Academic and scientific leadership was weaken the United States until the late 19th century, when it began to be concentrated in universities. A few major research-oriented schools were in or close by the largest cities, such as Harvard (Boston), Columbia (New York), Johns Hopkins (Baltimore) and Chicago. However, most were located in smaller cities or large towns such as Yale in New Haven, Connecticut; Cornell in Ithaca, New York; Princeton in Princeton, New Jersey; the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor; University of Illinois in Urbana; University of Wisconsin in Madison; University of California in Berkeley, and Stanford in the village of Stanford, California.[26]

Civil War

The cities played a major part in the Union war effort, providing soldiers, money, supplies, and media support. Discontent with the 1863 draft law led to riots in several cities and in rural areas as well. By far the most important were the New York City draft riots of July 13 to July 16, 1863.[27] Irish Catholic and other workers fought police, militia and regular army units until the Army used artillery to sweep the streets. Initially focused on the draft, the protests quickly expanded into violent attacks on blacks in New York City, with many killed on the streets.[28]

A study of the small Michigan cities of Grand Rapids and Niles shows an overwhelming surge of nationalism in 1861, whipping up enthusiasm for the war in all segments of society, and all political, religious, ethnic, and occupational groups. However by 1862 the casualties were mounting and the war was increasingly focused on freeing the slaves in addition to preserving the Union.[29] Copperhead Democrats called the war a failure and it became more and more a partisan Republican effort.[30]

Confederacy

Cities played a much less important part of the Confederacy. It was a heavily rural area. When the war started the largest cities in slave states were seized in 1861 by the Union, including Washington, Baltimore, Wheeling, Louisville, and St. Louis. The largest and most important Confederate city, New Orleans, was captured in 1862. All these cities became major logistic and strategic centers for the Union forces. All the remaining ports were blockaded by the summer of 1861, ending normal commercial traffic, with only very expensive blockade runners getting through. The largest remaining cities were Atlanta, the railroad center which was destroyed in 1864, in the national capital in Richmond which held out to the bitter end.

The overall decline in food supplies, made worse by the inadequate transportation system, led to serious shortages and high prices in Confederate cities. When bacon reached a dollar a pound in 1864, the poor white women of Richmond, Atlanta and many other cities began to riot; they broke into shops and warehouses to seize food. The women expressed their anger at ineffective state relief efforts, speculators, merchants and planters. As wives and widows of soldiers they were hurt by the inadequate welfare system.[31][32]

The eleven Confederate states in 1860 had 297 towns and cities with 835,000 people; of these 162 with 681,000 people were at one point occupied by Union forces. Eleven were destroyed or severely damaged by war action, including Atlanta (with an 1860 population of 9,600), Charleston, Columbia, and Richmond (with prewar populations of 40,500, 8,100, and 37,900, respectively); the eleven contained 115,900 people in the 1860 census, or 14% of the urban South. The number of people (as of 1860) who lived in the destroyed towns represented just over 1% of the Confederacy's 1860 population.[33]

Late 19th century growth

Lure of the metropolis

Jeffersonian America distrusted the city, and rural spokesmen repeatedly warned their young men away.[34] In 1881 The Evening Wisconsin newspaper warned cautious boys to stay on the farm. As paraphrased by historian Bayrd Still, the editor painted a grim contrast:

- Pure milk, wholesome water, mellow fruit, vegetables, and proper sleep and exercise are lacking in the city; and the "dense centers of population are unfavorable to moral growth as they are to physical development." Sharpness and deception characterize the city merchant, mechanic, and professional man as well. How different is the situation of the "sturdy farmer removed from the dust and smoke and filth and vice of the crowded city....Content in his cottage...why should he long for the fare and follies of the madding crowd in the Gay Metropolis?"

The response came from a Milwaukee newspaper editor in 1871, who boasted that the ambitious young man could not be stopped:

- The young man in the country no sooner elects for himself his course, than he makes for the nearest town. Scarcely has he grown familiar with his new surroundings, when the subtle attractions of the remoter city begin to tell upon him. There is no resisting it. It draws him like a magnet. Sooner or later, it is tolerably certain, he will be sucked into one of the great centers of life. [35]

Reformers

Historians have developed an elaborate typology of reformers in the late 19th century, focusing especially on the urban reformers.[36]

The Mugwumps Were reform minded Republicans who acted at the national level in the 1870s and 1880s, especially in 1884 when they split their ticket for Democrat Grover Cleveland.[37] The "Goo Goos" were the local equivalent: the middle-class reformers who sought "good government" regardless of party. They typically focused on urban sanitation, better schools, and lower trolley fares for the middle-class commuters. They especially demanded a nonpolitical civil service system to replace the "spoils of victory" approach by which the winners of an election replaced city and school employees. They often formed short-lived citywide organizations, such as The Committee of 70 in New York, the Citizens' Reform Association in Philadelphia, the Citizens' Association of Chicago, and the Baltimore Reform League. They sometimes one citywide elections, but were rarely reelected. Party regulars laughed at them for trying to be independent of the political party machines by forming nonpartisan tickets. The ridicule included suggestions that the reformers were not real men: they were sissies and "mollycoddles".[38]

By the 1890s, when historians call "structural reformers" were emerging; they were much more successful at reform, and marked the beginning of the Progressive era. They used national organizations, such as the National Municipal League, and focused on broader principles such as honesty, efficiency, economy, and centralized decision-making by experts. "Efficiency" was their watchword, they believed one of the problems with the machines was that they wasted enormous amounts of tax money by creating useless patronage jobs and payoffs to mid-level politicians.[39]

Social reformers emerged in the 18902, most famously Jane Addams Enter large complex network of reformers based at Hull House in Chicago.[40] They were less interested in civil service reform or revising the city charter, and concentrated instead on the needs of working class housing, child labor, sanitation and welfare. Protestant churches promoted their own group of reformers, mostly women activists demanding prohibition or sharp reductions in the baleful influence of the saloon in damaging family finances and causing family violence. Rural America was increasingly won over by the prohibitionists, but they rarely had success in the larger cities, where they were staunchly opposed by the large German and Irish elements.[41] However, the Women's Christian Temperance Union became well organized in cities of every size, and taught middle-class women the techniques of organization, proselytizing, and propaganda. Many of the WCTU veterans graduated into the woman's suffrage movement. Moving relentlessly from West to East, became the vote for women in state after state, and finally nationwide in 1920.[42][43]

Sanitation and public health

Sanitary conditions were bad throughout urban America in the 19th century. The worst conditions appeared in the largest cities, where the accumulation of human and horse waste built up on the city streets, where sewage systems were inadequate, and the water supply was of dubious quality.[44] Physicians took the lead in pointing out problems, and were of two minds on the causes. The older theory of contagion said that germs spread disease, but this theory was increasingly out of fashion by the 1840s or 1850s for two reasons. On the one hand it predicted too much-- microscopes demonstrated so many various microorganisms that there was no particular reason to associate any one of them with a specific disease. There was also a political dimension; a contagious theory of disease called for aggressive public health measures, which meant taxes and regulation the business community rejected. [45] Before the 1880s, most experts believed in the "Miasma theory" which attributed the spread of disease to "bad air" caused by the abundance of dirt and animal waste. It indicated the need for regular garbage pickup. By the 1880s, however, European discovery of the germ theory of disease proved decisive for the medical community, although popular belief never shook the old "bad air" theory. Medical attention shifted from curing the sick patient to stopping the spread of the disease in the first place. It indicated a system of quarantines, hospitalization, clean water, and proper sewage disposal.[46] Dr Charles V. Chapin (1856-1941), head of public health in Providence Rhode Island, was a tireless campaigner for the germ theory of disease, which he repeatedly validated with his laboratory studies. Chapin emphatically told popular audiences germs were the true culprit, not filth; that diseases were not indiscriminately transmitted through the smelly air; and that disinfection was not a cure-all. He paid little attention to environmental or chemical hazards in the air and water, or to tobacco smoking, since germs were not involved. They did not become a major concern of the public health movement until the 1960s.[47] The second stage of public health, building on the germ theory, brought in engineers to design elaborate water and sewer systems. Their expertise was welcomed, and many became city managers after that reform was introduced in the early 20th century.[48][49]

20th century

Progressive era: 1890s-1920s

During the Progressive Era a coalition of middle-class reform-oriented voters, academic experts And reformers hostile to the political machines introduced a series of reforms in urban America, designed to reduce waste and inefficiency and corruption, by introducing scientific methods, compulsory education and administrative innovations.

The pace was set in Detroit Michigan, where Republican mayor Hazen S. Pingree first put together the reform coalition.[50]

Many cities set up municipal reference bureaus to study the budgets and administrative structures of local governments. Progressive mayors were important in many cities,[51] such as Cleveland, Ohio (especially Mayor Tom Johnson); Toledo, Ohio;[52] Jersey City, New Jersey;[53] Los Angeles;[54] Memphis, Tennessee;[55] Louisville, Kentucky;[56] and many other cities, especially in the western states. In Illinois, Governor Frank Lowden undertook a major reorganization of state government.[57] Wisconsin was the stronghold of Robert LaFollette, who led a wing of the Republican Party. His Wisconsin Idea used the state university as a major source of ideas and expertise.[58]

One of the most dramatic changes came in Galveston, Texas were a devastating hurricane and flood overwhelmed the resources of local government. Reformers abolished political parties in municipal elections, and set up a five-man commission of experts to rebuild the city. The Galveston idea was simple, efficient, and much less conducive to corruption. If lessened the Democratic influences of the average voter, but multiplied the influence of the reform minded middle-class.[59] The Galveston plan was quickly copied by many other cities, especially in the West. By 1914 over 400 cities had nonpartisan elected commissions.[60] Dayton, Ohio Had its great flood in 1913, and responded with the innovation of a paid, non-political city manager, hired by the commissioners to run the bureaucracy; mechanical engineers were especially preferred.[61][62]

Urban planning

The Garden city movement, was brought over from England and evolved into the "Neighborhood Unit" form of development. In the early 1900s, as cars were introduced to city streets for the first time, residents became increasingly concerned with the number of pedestrians being injured by car traffic. The response, seen first in Radburn, New Jersey, was the Neighborhood Unit-style development, which oriented houses toward a common public path instead of the street. The neighborhood is distinctively organized around a school, with the intention of providing children a safe way to walk to school.[63][64]

The Great Depression

Urban America had enjoyed strong growth and steady prosperity in the 1920s . Large-scale immigration had ended in 1914, and never fully resumed , so that ethnic communities have become stabilized and Americanized. Upward mobility was the norm, in every sector of the population supported the rapidly growing high school system. After the stock market crash of October 1929, the nation's optimism suddenly turned negative, with both business investments and private consumption overwhelmed by a deepening pessimism that encouraged people to cut back and reduce their expectations. The economic damage to the cities was most serious in the collapse of 80 to 90 percent of the private sector construction industry. Cities and states started expanding their own construction programs as early as 1930, and they became a central feature of the New Deal, but private construction did not fully recover until after 1945. Many landlords so their rental income drained away and many went bankrupt. After construction, came the widespread downturn in heavy industry, especially manufacturing of durable goods such as automobiles, machinery, and refrigerators. The impact of unemployment was higher in the manufacturing centers in the East and Midwest, and lower in the South and West, which had less manufacturing. [65]

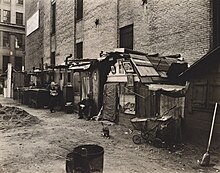

One visible effect of the depression was the advent of Hoovervilles, which were ramshackle assemblages on vacant lots of cardboard boxes, tents, and small rickety wooden sheds built by homeless people. Residents lived in shacks and begged for food or went to soup kitchens. The term was coined by Charles Michelson, publicity chief of the Democratic National Committee, who referred sardonically to President Herbert Hoover whose policies he blamed for the depression.[66]

Unemployment reached 25 percent in the worst days of 1932-33, but it was unevenly distributed. Job losses were less severe among women than men, among workers in nondurable industries (such as food and clothing), in services and sales, and in government jobs. The least skilled inner city men had much higher unemployment rates, as did young people who had a hard time getting their first job, and men over the age of 45 who if they lost their job would seldom find another one because employers had their choice of younger men. Millions were hired in the Great Depression, but men with weaker credentials were never hired, and fell into a long-term unemployment trap. The migration that brought millions of farmers and townspeople to the bigger cities in the 1920s suddenly reversed itself, as unemployment made the cities unattractive, and the network of kinfolk and more ample food supplies made it wise for many to go back. [67] City governments in 1930-31 tried to meet the depression by expanding public works projects, as president Herbert Hoover strongly encouraged. However tax revenues were plunging, and the cities as well as private relief agencies were totally overwhelmed by 1931 men were unable to provide significant additional relief. They fell back on the cheapest possible relief, soup kitchens which provided free meals for anyone who showed up. [68] After 1933 new sales taxes and infusions of federal money helped relieve the fiscal distress of the cities, but the budgets did not fully recover until 1941.

The federal programs launched by Hoover and greatly expanded by president Roosevelt’s New Deal used massive construction projects to try to jump start the economy and solve the unemployment crisis. The alphabet agencies ERA, CCC, FERA, WPA and PWA built and repaired the public infrastructure in dramatic fashion, but did little to foster the recovery of the private sector. FERA, CCC and especially WPA focused on providing unskilled jobs for long-term unemployed men.

The Democrats won easy landslides in 1932 and 1934, and an even bigger one in 1936; the hapless Republican Party seemed doomed. The Democrats capitalized on the magnetic appeal of Roosevelt to urban America. The key groups were low skilled ethnics, especially Catholics, Jews, and blacks. The Democrats promised and delivered in terms of beer, political recognition, labor union membership, and relief jobs. The city machines were stronger than ever, for they mobilize their precinct workers to help families who needed help the most navigate the bureaucracy and get on relief. FDR won the vote of practically every group in 1936, including taxpayers, small business and the middle class. However the Protestant middle class voters but turned sharply against him after the recession of 1937-38 undermined repeated promises that recovery was at hand. Historically, local political machines were primarily interested in controlling their wards and citywide elections; the smaller the turnout on election day, the easier it was to control the system. However for Roosevelt to win the presidency in 1936 and 1940, he needed to carry the electoral college and that meant he needed the largest possible majorities in the cities to overwhelm the out state vote. The machines came through for him.[69] The 3.5 million voters on relief payrolls during the 1936 election cast 82% percent of their ballots for Roosevelt. The rapidly growing, energetic labor unions, chiefly based in the cities, turned out 80% for FDR, as did Irish, Italian and Jewish communities. In all, the nation's 106 cities over 100,000 population voted 70% for FDR in 1936, compared to his 59% elsewhere. Roosevelt worked very well with the big city machines, with the one exception of his old nemesis, Tammany Hall in Manhattan. There he supported the complicated coalition built around the nominal Republican Fiorello La Guardia, and based on Jewish and Italian voters mobilized by labor unions. [70]

In 1938, the Republicans made an unexpected comeback, and Roosevelt’s efforts to purge the Democratic Party of his political opponents backfired badly. The conservative coalition of Northern Republicans and Southern Democrats took control of Congress, outvoted the urban liberals, and handed the expansion of New Deal ideas. Roosevelt survived in 1940 thanks to his margin in the Solid South and in the cities. In the North the cities over 100,000 gave Roosevelt 60% of their votes, while the rest of the North favored the GOP candidate Wendell Willkie 52%-48%.[71]

With the start of full-scale war mobilization in the summer of 1940, the economies of the cities rebounded. Even before Pearl Harbor, Washington pumped massive investments into new factories and funded round-the-clock munitions production, guaranteeing a job to anyone who showed up at the factory gate.[72] The war brought a restoration of prosperity and hopeful expectations for the future across the nation. It had the greatest impact on the cities of the West Coast, especially Los Angeles, San Diego, San Francisco, Portland and Seattle.[73]

See also

- History of Boston

- History of Chicago

- History of Los Angeles

- History of New York

- History of Philadelphia

- Suburb

- Urban history

- Urbanism

Notes

- ^ Michael Frisch, "American urban history as an example of recent historiography." History and Theory (1979): 350-377. in JSTOR

- ^ Steven Conn, Americans Against the City: Anti-Urbanism in the Twentieth Century (2014)

- ^ Bruce M. Stave, ed., The Making of Urban History: Historiography through Oral History (1977) in Google

- ^ Raymond A. Mohl, "The History of the American City," in William H. Cartwright and Richard L. Watson Jr. eds., Reinterpretation of American History and Culture (1973) pp 165-205 quote p 165

- ^ Carl Bridenbaugh, Cities in the Wilderness-The First Century of Urban Life in America 1625-1742 (1938) online edition

- ^ Carl Bridenbaugh, Cities in Revolt: Urban Life in America, 1743-1776 (1955), pp 147, 332

- ^ Benjamin L. Carp, "Cities in review," Common-Place (July 2003) 3#4 online

- ^ Jacob Ernest Cooke, ed., Encyclopedia of the North American colonies (1993) 1: 113-154, 233-244.

- ^ Seth Rockman, "Work in the Cities of Colonial British North America," Journal of Urban History (2007) 33#6 pp 1021-1032

- ^ Seth Rockman, "Class and the History of Working People in the Early Republic." Journal of the Early Republic (2005) 25#4 pp: 527-535. online

- ^ Peter Wood, Origins of American Slavery (1997), pp. 64–65.

- ^ Walter J. Fraser, Charleston! Charleston!: The History of a Southern City (1991)

- ^ Benjamin L. Carp, Rebels Rising: Cities and the American Revolution (2007) online edition

- ^ Gary B. Nash, The Urban Crucible: The Northern Seaports and the Origins of the American Revolution (2nd ed. 1986) pp 240-47; the first edition of 1979 was entitled Urban Crucible: Social Change, Political Consciousness, and the Origins of the American Revolution)

- ^ Robert A. East, "The Business Entrepreneur in a Changing Colonial Economy, 1763-1795," Journal of Economic History (May, 1946), Vol. 6, Supplement pp. 16-27 in JSTOR

- ^ Richard C. Wade, "An Agenda for Urban History," in Herbert J. Bass, ed., The State of American History (1970) pp 58-59

- ^ Russel Blaine Nye, The Cultural Life of the New Nation: 1776-1830 (1960) pp 127-28

- ^ Curtis P. Nettles, The Emergence of a National Economy, 1775-1815 (1962) remains the best economic overview.

- ^ John Allen Krout and Dixon Ryan Fox, The Completion of Independence, 1790–1830 (1944) is a wide-ranging social history of the new nation; see pp 1-73

- ^ Richard C. Wade, The urban frontier: pioneer life in early Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Lexington, Louisville, and St. Louis (1959).

- ^ The totals include suburbs, which were small except in the case of Boston. "George Rogers Taylor, "The Beginnings of Mass Transportation in Urban America: Part 1," Smithsonian Journal of History (1966) 1:36

- ^ George Rogers Taylor, The transportation revolution, 1815-1860 (1951) pp 388-89.

- ^ Robert G. Albion, "New York Port and its disappointed rivals, 1815-1860." Journal of Business and Economic History (1931) 3: 602-629.

- ^ Julius Rubin, "Canal or railroad? Imitation and innovation in the response to the Erie canal in Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Boston." Transactions of the American Philosophical Society (1961): 1-106.

- ^ Lawrence V. Roth, "The Growth of American Cities." Geographical Review (1918) 5#5 pp: 384-398. in JSTOR

- ^ Arthur Meier Schlesinger, The Rise of the City: 1878-1898 (1933) pp 82-87, 212-16, 247-48

- ^ Barnet Schecter, The Devil's Own Work: The Civil War Draft Riots and the Fight to Reconstruct America (2005)

- ^ The New York City Draft Riots In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626–1863, by Leslie M. Harris

- ^ Peter Bratt, "A Great Revolution in Feeling: The American Civil War in Niles and Grand Rapids, Michigan," Michigan Historical Review (2005) 31#2 pp 43–66.

- ^ Martin J. Hershock, "Copperheads and Radicals: Michigan Partisan Politics during the Civil War Era, 1860–1865," Michigan Historical Review (1992) 18#1 pp 28–69

- ^ Stephanie McCurry, "'Bread or Blood!'" Civil War Times (2011) 50#3 pp 36–41.

- ^ Teresa Crisp Williams, and David Williams, "'The Women Rising': Cotton, Class, and Confederate Georgia's Rioting Women," Georgia Historical Quarterly, (2002) 86#12 pp. 49–83

- ^ Paul F. Paskoff, "Measures of War: A Quantitative Examination of the Civil War's Destructiveness in the Confederacy," Civil War History, (2008) 54#1 pp 35–62

- ^ Schlesinger, The rise of the city pp 53-77

- ^ Bayrd Still, "Milwaukee, 1870-1900: The Emergence of a Metropolis," Wisconsin Magazine of History (1939) 23#2 pp. 138-162 in JSTOR , quotes at pp 143, and 139

- ^ Raymond A Mohl, The New City: Urban America in the Industrial Age, 1860-1920 (1985) pp 108-37, 218-220

- ^ Gerald W. McFarland, "The New York mugwumps of 1884: A profile." Political Science Quarterly (1963): 40-58 in JSTOR.

- ^ Kevin P. Murphy (2013). Political Manhood: Red Bloods, Mollycoddles, and the Politics of Progressive Era Reform. Columbia UP. p. 64.

- ^ Martin J. Schiesl, The politics of efficiency: Municipal administration and reform in America, 1880-1920 (1980)

- ^ Kathryn Kish Sklar, "Hull House in the 1890s: A community of women reformers." Signs (1985): 658-677 in JSTOR

- ^ Mohl, The New City pp 115-33

- ^ Ruth Bordin, Woman and Temperance: The quest for power and liberty, 1873-1900 (1981)

- ^ Elisabeth S. Clemens, "Organizational repertoires and institutional change: Women's groups and the transformation of US politics, 1890-1920." American journal of sociology (1993): 755-798. in JSTOR

- ^ Stuart Galishoff, Newark: the nation's unhealthiest city, 1832-1895 (1988).

- ^ Thomas Neville Bonner, Medicine in Chicago: 1850-1950: A chapter in the social and scientific development of a city (1957) pp 24-39

- ^ Martin V. Melosi, The Sanitary City: Urban Infrastructure in America from Colonial Times to the Present (2000)

- ^ James H. Cassedy, Charles V. Chapin and the Public Health Movement (1962).

- ^ Stanley K. Schultz, and Clay McShane. "To engineer the metropolis: sewers, sanitation, and city planning in late-nineteenth-century America." Journal of American History (1978): 389-411. in JSTOR

- ^ Jon C. Teaford, The Unheralded Triumph: City Government in America, 1870-1900 (1984) pp 134-41

- ^ Melvin G. Holli, Reform in Detroit: Hazen S. Pingree and urban politics (1969).

- ^ Kenneth Finegold, "Traditional Reform, Municipal Populism, and Progressivism," Urban Affairs Review, (1995) 31#1 pp 20-42

- ^ Arthur E. DeMatteo, "The Progressive As Elitist: 'Golden Rule' Jones And The Toledo Charter Reform Campaign of 1901," Northwest Ohio Quarterly, (1997) 69#1 pp 8-30

- ^ Eugene M. Tobin, "The Progressive as Single Taxer: Mark Fagan and the Jersey City Experience, 1900–1917," American Journal of Economics & Sociology, (1974) 33#3 pp 287–298

- ^ Martin J. Schiesl, "Progressive Reform in Los Angeles under Mayor Alexander, 1909–1913," California Historical Quarterly, (1975) 534#1, pp:37-56

- ^ G. Wayne Dowdy, "'A Business Government by a Business Man': E. H. Crump as a Progressive Mayor, 1910–1915," Tennessee Historical Quarterly, (2001) 60#3 3, pp 162–175

- ^ William E. Ellis, "Robert Worth Bingham and Louisville Progressivism, 1905–1910," Filson Club History Quarterly, (1980) 54#2 pp 169–195

- ^ William Thomas Hutchinson, Lowden of Illinois: the life of Frank O. Lowden (1957) vol 2

- ^ "Progressivism and the Wisconsin Idea". Wisconsin Historical Society. 2008.

- ^ Bradley R. Rice, "The Galveston Plan of City Government by Commission: The Birth of a Progressive Idea." Southwestern Historical Quarterly (1975): 365-408.

- ^ Bradley R. Rice, Progressive Cities: The Commission Government Movement in America, 1901–1920 (2014).

- ^ Stefan Couperus, "The managerial revolution in local government: municipal management and the city manager in the USA and the Netherlands 1900–1940." Management & Organizational History (2014) 9#4 pp: 336-352.

- ^ Richard J. Stillman, The rise of the city manager: A public professional in local government (U of New Mexico Press, 1974)

- ^ Carol Ann Christensen, The American garden city and the new towns movement (1986).

- ^ Daniel Schaffer, Garden Cities for America: The Radburn Experience (Temple University Press, 1982)

- ^ William H, Mullins, The Depression and the Urban West Coast, 1929-1933: Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, and Portland (2000)

- ^ Hans Kaltenborn, It Seems Like Yesterday (1956) p. 88

- ^ Richard J. Jensen, "The causes and cures of unemployment in the Great Depression." Journal of Interdisciplinary History (1989): 553-583 in JSTOR ; online copy

- ^ Janet Poppendieck, Breadlines knee-deep in wheat: Food assistance in the Great Depression (2014)

- ^ Roger Biles, Big City Boss in Depression and War: Mayor Edward J. Kelly of Chicago (1984).

- ^ Mason B. Williams, City of Ambition: FDR, LaGuardia, and the Making of Modern New York (2013)

- ^ Richard Jensen, "The cities reelect Roosevelt: Ethnicity, religion, and class in 1940." Ethnicity. An Interdisciplinary Journal of the Study of Ethnic Relations (1981) 8#2: 189-195.

- ^ Jon C. Teaford, The twentieth-century American city (1986) pp 90-96.

- ^ Roger W. Lotchin, The Bad City in the Good War: San Francisco, Los Angeles, Oakland, and San Diego (2003)

Further reading

Surveys

- Bridenbaugh, Carl. Cities in the Wilderness: The First Century of Urban Life in America, 1625-1742 (1938)

- Bridenbaugh, Carl. Cities in Revolt: Urban Life in America, 1743-1776 (1955)

- Brownell, Blaine A. And Goldfield, David R. The City in southern history: The growth of urban civilization in the South (1977)

- Glaab, Charles Nelson, and A. Theodore Brown. History of Urban America (1967)

- Kirkland, Edward C. Industry Comes of Age, Business, Labor, and Public Policy 1860-1897 (1961) esp 237-61

- McKelvey, Blake. The urbanization of America, 1860-1915 (1963), 390ppy

- McKelvey, Blake. The Emergence of Metropolitan America, 1915-1960 (1968), 320pp

- Miller, Zane I. Urbanization of Modern America: A Brief History (2nd ed. 1987)

- Monkkonen, Eric H. America Becomes Urban: The Development of U.S. Cities and Towns, 1780-1980 (1990), 336pp

- Rubin, Jasper. "Planning and American Urbanization since 1950." in Craig E. Colten and Geoffrey L. Buckley, eds. North American Odyssey: Historical Geographies for the Twenty-first Century (2014): 395-412

- Schlesinger, Arthur M. The rise of the city: 1878-1898 (1933), A social history

- Still, Bayrd. "Patterns of Mid-Nineteenth Century Urbanization in the Middle West," Mississippi Valley Historical Review (1941) 28#2 pp. 187-206 in JSTOR

- Taylor, George Rogers. "The Beginnings Of Mass Transportation In Urban America." Smithsonian Journal of History (1966) 1#2 pp 35-50; 1#3 pp 31-54; partly reprinted in Wakstein, ed., The Urbanization of America (1970) pp 128-50; Covers 1820-1960

- Teaford, Jon C. Cities of the Heartland: The Rise and Fall of the Industrial Midwest (1993)

- Teaford, Jon C. The Metropolitan Revolution: The Rise of Post-Urban America (2006)

- Teaford, Jon C. The Unheralded Triumph: City Government in America, 1870-1900 (1984)

- wade, Richard C. The Urban Frontier - Pioneer Life In Early Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Lexington, Louisville, And St. Louis (2nd ed. 1976)

Pathologies & public health

- Cain, Louis P. "Sanitation in Chicago: A Strategy for a Lakefront Metropolis," Encyclopedia of Chicago (2004) online

- Crane, Brian D. "Filth, garbage, and rubbish: Refuse disposal, sanitary reform, and nineteenth-century yard deposits in Washington, DC." Historical Archaeology (2000): 20-38. in JSTOR

- Duffy, John. The sanitarians: a history of American public health (1992)

- Larsen, Lawrence H. "Nineteenth-Century Street Sanitation: A Study of Filth and Frustration," Wisconsin Magazine of History (1969) 52#3 pp. 239-247 in JSTOR

- Melosi, Martin V. Garbage in the cities: refuse reform and the environment (2004)

- Mohl, Raymond A. "Poverty, pauperism, and social order in the preindustrial American City, 1780-1840." Social Science Quarterly (1972): 934-948. in JSTOR

- Rosenberg, Charles E. The cholera years: The United States in 1832, 1849, and 1866 (1962)

City biographies

- Burrows, Edwin G. and Wallace, Mike (1999). Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-195-11634-8., The standard scholarly history, 1390pp

- Homberger, Eric. The Historical Atlas of New York City: A Visual Celebration of 400 Years of New York City's History (2005)

- Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (1995). The Encyclopedia of New York City. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300055366.; second edition 2010

- Pierce, Bessie Louise. A History of Chicago from Town to Ciry 1848-1871 Vol II (1940)

- Pierce, Bessie Louise. A History of Chicago, Volume III: The Rise of a Modern City, 1871-1893 (1957) excerpt

- Reiff, Janice L., Ann Durkin Keating and James R. Grossman, eds. The Encyclopedia of Chicago (2004), with thorough coverage by scholars in 1120 pages of text, maps and photos. it is online free

Historiography

- Abbott, Carl. "Urban History for Planners," Journal of Planning History, Nov 2006, Vol. 5 Issue 4, pp 301–313

- Ebner, Michael H. "Re-Reading Suburban America: Urban Population Deconcentration, 1810-1980," American Quarterly (1985) 37#3 pp. 368-381 in JSTOR

- Engeli, Christian, and Horst Matzerath. Modern urban history research in Europe, USA, and Japan: a handbook (1989) in GoogleBooks

- Frisch, Michael. "American urban history as an example of recent historiography." History and Theory (1979): 350-377. in JSTOR

- Gillette Jr., Howard, and Zane L. Miller, eds. American Urbanism: A Historiographical Review (1987) online

- Lees, Lynn Hollen. "The Challenge of Political Change: Urban History in the 1990s," Urban History, (1994), 21#1 pp. 7–19.

- McManus, Ruth, and Philip J. Ethington, "Suburbs in transition: new approaches to suburban history," Urban History, Aug 2007, Vol. 34 Issue 2, pp 317–337

- McShane, Clay. "The State of the Art in North American Urban History," Journal of Urban History (2006) 32#4 pp 582–597, identifies a loss of influence by such writers as Lewis Mumford, Robert Caro, and Sam Warner, a continuation of the emphasis on narrow, modern time periods, and a general decline in the importance of the field. Comments by Timothy Gilfoyle and Carl Abbott contest the latter conclusion.

- Mohl, Raymond A. "The History of the American City," in William H. Cartwright and Richard L. Watson Jr. eds., Reinterpretation of American History and Culture (1973) pp 165–205, overview of historiography

- Nickerson, Michelle. "Beyond Smog, Sprawl, and Asphalt: Developments in the Not-So-New Suburban History," Journal of Urban History (2015) 41#1 pp 171–180. covers 1934 to 2011. DOI: 10.1177/0096144214551724.

- Schlesinger, Arthur M. "The City in American History," Mississippi Valley Historical Review (1940) 27#1 pp. 43-66 in JSTOR influential manifesto calling for an urban interpretation of all of American history

- Seligman, Amanda I. "Urban History Encyclopedias: Public, Digital, Scholarly Projects." Public Historian (2013) 35#2 pp: 24-35.

- Stave, Bruce M., ed. The making of urban history: Historiography through oral history (1977), interviews with leading scholars, previously published in Journal of Urban History

Anthologies of scholarly articles

- Callow, Alexander B., Jr., ed. American Urban History: An Interpretive Reader with Commentaries (3rd ed. 1982) 33 topical essays by scholars

- Chudacoff, Howard et al. eds. Major Problems in American Urban and Suburban History (2004)

- Goldfield, David. ed. Encyclopedia of American Urban History (2 vol 2006); 1056 pp; excerpt and text search

- Handlin, Oscar, and John Burchard, eds. The Historian and the City (1963)

- Holli, Melvin G. and Peter D. A. Jones, eds. Biographical Dictionary of American Mayors, 1820-1980: Big City Mayors (1981), essays by scholars on the most important mayors of Baltimore, Boston, Buffalo, Chicago, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Detroit, Los Angeles, Milwaukee, New Orleans, New York, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and St. Louis.

- Shumsky, Larry. Encyclopedia of Urban America: The Cities and Suburbs (2 vol 1998)

- Wakstein, Allen M., ed. The Urbanization of America: An Historical Anthology (1970) 510 pp; 37 topical essays by scholars

Primary sources

- Glaab, Charles N., ed. The American city: a documentary history1063 and four (1963) 491pp; selected primary documents

- Jackson, Kenneth T. and David S. Dunbar, eds. Empire City: New York Through the Centuries (2005), 1015 pages of excerpts excerpt

- Pierce, Bessie Louise, ed. As Others See Chicago: Impressions of Visitors, 1673-1933 (1934)

- Still, Bayrd, ed. Mirror for Gotham: New York as Seen by Contemporaries from Dutch Days to the Present (New York University Press, 1956) online edition