Measles: Difference between revisions

I'm deleting MMR controversy information from this article for the time being; this information is currently too lengthy for inclusion and is in greater detail elsewhere on WP |

|||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

{{TOC limit|3}} |

{{TOC limit|3}} |

||

==Signs and symptoms== |

==Signs and symptoms== |

||

[[File:Morbillivirus measles infection.jpg|thumb|Skin of a patient after 3 days of measles infection]] |

[[File:Morbillivirus measles infection.jpg|left|thumb|Skin of a patient after 3 days of measles infection]] |

||

[[File:Koplik spots, measles 6111 lores.jpg|thumb|Presentation of “Koplik's spots” on the third pre-eruptive day, indicative of the beginning onset of measles]] |

[[File:Koplik spots, measles 6111 lores.jpg|thumb|Presentation of “Koplik's spots” on the third pre-eruptive day, indicative of the beginning onset of measles]] |

||

The classic signs and symptoms of measles include four-day fevers (the 4 D's) and the three C's—[[cough]], [[coryza]] (head cold), and [[conjunctivitis]] (red eyes)—along with fever and rashes. The fever may reach up to {{convert|40|C}}. [[Koplik's spots]] seen inside the mouth are [[pathognomonic]] (diagnostic) for measles, but are temporary and therefore rarely seen. Their recognition, before the affected person reaches maximum infectivity, can be used to reduce spread of epidemics.<ref name=baxby>{{cite journal | author = Baxby D | title = Classic Paper: Henry Koplik. The diagnosis of the invasion of measles from a study of the exanthema as it appears on the buccal membrane | journal = Reviews in Medical Virology | volume = 7 | issue = 2 | pages = 71–4 | year = 1997 | pmid = 10398471 | doi = 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1654(199707)7:2<71::AID-RMV185>3.0.CO;2-S }}</ref> |

The classic signs and symptoms of measles include four-day fevers (the 4 D's) and the three C's—[[cough]], [[coryza]] (head cold), and [[conjunctivitis]] (red eyes)—along with fever and rashes. The fever may reach up to {{convert|40|C}}. [[Koplik's spots]] seen inside the mouth are [[pathognomonic]] (diagnostic) for measles, but are temporary and therefore rarely seen. Their recognition, before the affected person reaches maximum infectivity, can be used to reduce spread of epidemics.<ref name=baxby>{{cite journal | author = Baxby D | title = Classic Paper: Henry Koplik. The diagnosis of the invasion of measles from a study of the exanthema as it appears on the buccal membrane | journal = Reviews in Medical Virology | volume = 7 | issue = 2 | pages = 71–4 | year = 1997 | pmid = 10398471 | doi = 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1654(199707)7:2<71::AID-RMV185>3.0.CO;2-S }}</ref> |

||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

Between 1987 and 2000, the case fatality rate across the [[United States]] was three measles-attributable deaths per 1000 cases, or 0.3%.<ref name="The Clinical Significance of Measles: A Review"> |

Between 1987 and 2000, the case fatality rate across the [[United States]] was three measles-attributable deaths per 1000 cases, or 0.3%.<ref name="The Clinical Significance of Measles: A Review"> |

||

{{cite journal | author = Perry RT, Halsey NA | title = The Clinical Significance of Measles: A Review | journal = The Journal of Infectious Diseases | volume = 189 | issue = S1 | pages = S4–16 | date = May 1, 2004 | pmid = 15106083 | doi = 10.1086/377712 }}</ref> |

{{cite journal | author = Perry RT, Halsey NA | title = The Clinical Significance of Measles: A Review | journal = The Journal of Infectious Diseases | volume = 189 | issue = S1 | pages = S4–16 | date = May 1, 2004 | pmid = 15106083 | doi = 10.1086/377712 }}</ref> |

||

In [[developing country|underdeveloped nation]]s with high rates of [[malnutrition]] and poor [[healthcare]], fatality rates have been as high as 28%.<ref name="The Clinical Significance of Measles: A Review"/> In [[immunodeficiency|immunocompromised]] persons (e.g., people with [[AIDS]]) the fatality rate is approximately 30%.<ref name="Sension1988">{{cite journal | author = Sension MG, Quinn TC, Markowitz LE, Linnan MJ, Jones TS, Francis HL, Nzilambi N, Duma MN, Ryder RW | title = Measles in hospitalized African children with human immunodeficiency virus | journal = American Journal of Diseases of Children (1960) | volume = 142 | issue = 12 | pages = 1271–2 | year = 1988 | pmid = 3195521 | doi = 10.1001/archpedi.1988.02150120025021 }}</ref> |

In [[developing country|underdeveloped nation]]s with high rates of [[malnutrition]] and poor [[healthcare]], fatality rates have been as high as 28%.<ref name="The Clinical Significance of Measles: A Review"/> In [[immunodeficiency|immunocompromised]] persons (e.g., people with [[AIDS]]) the fatality rate is approximately 30%.<ref name="Sension1988">{{cite journal | author = Sension MG, Quinn TC, Markowitz LE, Linnan MJ, Jones TS, Francis HL, Nzilambi N, Duma MN, Ryder RW | title = Measles in hospitalized African children with human immunodeficiency virus | journal = American Journal of Diseases of Children (1960) | volume = 142 | issue = 12 | pages = 1271–2 | year = 1988 | pmid = 3195521 | doi = 10.1001/archpedi.1988.02150120025021 }}</ref> Risk factors for severe measles and its complications include: [[malnutrition]];<ref name=medscape /><ref>{{cite journal | author = Polonsky JA, Ronsse A, Ciglenecki I, Rull M, Porten K | title = High levels of mortality, malnutrition, and measles, among recently-displaced Somali refugees in Dagahaley camp, Dadaab refugee camp complex, Kenya, 2011 | journal = Conflict and Health | volume = 7 | issue = 1 | pages = 1 | year = 2013 | pmid = 23339463 | pmc = 3607918 | doi = 10.1186/1752-1505-7-1 }}</ref> underlying immunodeficiency;<ref name=medscape /> [[pregnancy]];<ref name=medscape /><ref>{{cite journal | author = Kanda E, Yamaguchi K, Hanaoka M, Matsui H, Sago H, Kubo T | title = Low titers of measles antibodies in Japanese pregnant women: A single-center study | journal = The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research | volume = 39 | issue = 2 | pages = 500–503 | year = 2013 | pmid = 22925573 | pmc = | doi = 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2012.01997.x }}</ref> and [[vitamin A deficiency]].<ref name=medscape >{{cite report|author=Chen S.S.P.|date=October 3, 2011|title=Measles|url=http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/966220-overview|publisher=Medscape}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Vitamin A|url=http://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminA-HealthProfessional/}}</ref> |

||

==Cause== |

==Cause== |

||

[[File:Measles virus.JPG|thumb|An electron micrograph of the measles virus.]] |

|||

{{Taxobox |

|||

| ⚫ | Measles is caused by the [[measles virus]], a single-stranded, negative-sense, enveloped RNA virus of the genus ''[[Morbillivirus]]'' within the family ''[[Paramyxoviridae]]''. The virus was first isolated in 1954 by [[Nobel Laureate]] [[John F. Enders]] and Thomas Peebles, who were careful to point out that the isolations were made from patients who had Koplik's spots.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Enders JF, Peebles TC | title = Propagation in tissue culture of cytopathogenic agents from patients with measles | journal = Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine (New York, N.Y.) | volume = 86 | issue = 2 | pages = 277–86 | year = 1954 | pmid = 13177653 | doi=10.3181/00379727-86-21073}}</ref> Humans are the natural hosts of the virus; no other animal reservoirs are known to exist. This highly contagious virus is spread by coughing and sneezing via close personal contact or direct contact with secretions. Risk factors for measles virus infection include: [[immunodeficiency]] caused by [[HIV]] or AIDS,<ref>{{cite journal | author = Gowda VK, Sukanya V | title = Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome with Subacute Sclerosing Panencephalitis | journal = Pediatric Neurology | volume = 47 | issue = 5 | pages = 379–381 | year = 2012 | pmid = 23044024 | pmc = | doi = 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2012.06.020 }}</ref> [[leukemia]],<ref>{{cite journal | author = Breitfeld V, Hashida Y, Sherman FE, Odagiri K, Yunis EJ | title = Fatal measles infection in children with leukemia | journal = Laboratory Investigation; A Journal of Technical Methods and Pathology | volume = 28 | issue = 3 | pages = 279–291 | year = 1973 | pmid = 4348408 }}</ref> [[Alkylation#Alkylating agents|alkylating agents]], or [[Corticosteroid#Uses of corticosteroids|corticosteroid therapy]], regardless of immunization status;<ref name=medscape /> travel to areas where measles is endemic or contact with travelers to endemic areas;<ref name=medscape /> and the loss of passive, inherited antibodies before the age of routine immunization.<ref name=medscape /> |

||

| color = violet |

|||

| name = Measles |

|||

| image = Measles virus.JPG |

|||

| image_width = 180 px |

|||

| image_caption = Measles virus [[electron micrograph]] |

|||

| virus_group = v |

|||

| ordo = ''[[Mononegavirales]]'' |

|||

| familia = ''[[Paramyxoviridae]]'' |

|||

| subfamilia = ''[[Paramyxovirinae]]'' |

|||

| genus = ''[[Morbillivirus]]'' |

|||

| species = '''''Measles virus''''' |

|||

}} |

|||

| ⚫ | Measles is caused by the [[measles virus]], a single-stranded, negative-sense, enveloped RNA virus of the genus ''[[Morbillivirus]]'' within the family ''[[Paramyxoviridae]]''. The virus was first isolated in 1954 by [[Nobel Laureate]] [[John F. Enders]] and Thomas Peebles, who were careful to point out that the isolations were made from patients who had Koplik's spots.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Enders JF, Peebles TC | title = Propagation in tissue culture of cytopathogenic agents from patients with measles | journal = Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine (New York, N.Y.) | volume = 86 | issue = 2 | pages = 277–86 | year = 1954 | pmid = 13177653 | doi=10.3181/00379727-86-21073}}</ref> Humans are the natural hosts of the virus; no other animal reservoirs are known to exist. This highly contagious virus is spread by coughing and sneezing via close personal contact or direct contact with secretions. |

||

Risk factors for measles virus infection include the following: |

|||

*[[Immunodeficiency]] caused by [[HIV]] or AIDS,<ref>{{cite journal | author = Gowda VK, Sukanya V | title = Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome with Subacute Sclerosing Panencephalitis | journal = Pediatric Neurology | volume = 47 | issue = 5 | pages = 379–381 | year = 2012 | pmid = 23044024 | pmc = | doi = 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2012.06.020 }}</ref> [[leukemia]],<ref>{{cite journal | author = Breitfeld V, Hashida Y, Sherman FE, Odagiri K, Yunis EJ | title = Fatal measles infection in children with leukemia | journal = Laboratory Investigation; A Journal of Technical Methods and Pathology | volume = 28 | issue = 3 | pages = 279–291 | year = 1973 | pmid = 4348408 }}</ref> [[Alkylation#Alkylating agents|alkylating agents]], or [[Corticosteroid#Uses of corticosteroids|corticosteroid therapy]], regardless of immunization status<ref name=medscape /> |

|||

*Travel to areas where measles is endemic or contact with travelers to endemic areas<ref name=medscape /> |

|||

*The loss of passive, inherited antibodies before the age of routine immunization<ref name=medscape /> |

|||

Risk factors for severe measles and its complications include the following: |

|||

*[[Malnutrition]]<ref name=medscape /><ref>{{cite journal | author = Polonsky JA, Ronsse A, Ciglenecki I, Rull M, Porten K | title = High levels of mortality, malnutrition, and measles, among recently-displaced Somali refugees in Dagahaley camp, Dadaab refugee camp complex, Kenya, 2011 | journal = Conflict and Health | volume = 7 | issue = 1 | pages = 1 | year = 2013 | pmid = 23339463 | pmc = 3607918 | doi = 10.1186/1752-1505-7-1 }}</ref> |

|||

*Underlying immunodeficiency<ref name=medscape /> |

|||

*[[Pregnancy]]<ref name=medscape /><ref>{{cite journal | author = Kanda E, Yamaguchi K, Hanaoka M, Matsui H, Sago H, Kubo T | title = Low titers of measles antibodies in Japanese pregnant women: A single-center study | journal = The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research | volume = 39 | issue = 2 | pages = 500–503 | year = 2013 | pmid = 22925573 | pmc = | doi = 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2012.01997.x }}</ref> |

|||

*[[Vitamin A deficiency]]<ref name=medscape >{{cite report|author=Chen S.S.P.|date=October 3, 2011|title=Measles|url=http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/966220-overview|publisher=Medscape}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Vitamin A|url=http://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminA-HealthProfessional/}}</ref> |

|||

==Diagnosis== |

==Diagnosis== |

||

| Line 67: | Line 42: | ||

==Prevention== |

==Prevention== |

||

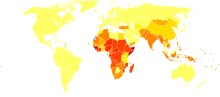

[[File:Measles vaccination coverage world.svg|thumb|Rates of measles vaccination worldwide]] |

[[File:Measles vaccination coverage world.svg|left|thumb|Rates of measles vaccination worldwide]] |

||

{{further2|[[Measles vaccine]], [[MMR vaccine]], and [[MMR vaccine controversy]]}} |

|||

[[File:Measles US 1944-2007 inset.png|thumb|Measles cases reported in the United States.]] |

|||

[[File:Measles incidence England&Wales 1940-2007.png|thumb|Measles cases reported in England and [[Wales]].]] |

|||

In developed countries, children are immunized against measles at 12 months, generally as part of a three-part [[MMR vaccine]] (measles, [[mumps]], and [[rubella]]). The vaccination is generally not given earlier than this because sufficient antimeasles [[immunoglobulins]] (antibodies) are acquired via the [[placenta]] from the mother during pregnancy may persist to prevent the vaccine viruses from being effective.{{citation needed|date=January 2014}} A second dose is usually given to children between the ages of four and five, to increase rates of immunity. Vaccination rates have been high enough to make measles relatively uncommon. Adverse reactions to vaccination are rare, with fever and pain at the injection site being the most common. Life-threatening adverse reactions occur in less than one per million vaccinations (<0.0001%).<ref name=cubavac >{{cite journal | author = Galindo BM, Concepción D, Galindo MA, Pérez A, Saiz J | title = Vaccine-related adverse events in Cuban children, 1999–2008 | journal = MEDICC Review | volume = 14 | issue = 1 | pages = 38–43 | year = 2012 | pmid = 22334111 | doi = | url = http://www.medicc.org/mediccreview/index.php?issue=19&id=237&a=vahtml | publisher = }}</ref> |

In developed countries, children are immunized against measles at 12 months, generally as part of a three-part [[MMR vaccine]] (measles, [[mumps]], and [[rubella]]). The vaccination is generally not given earlier than this because sufficient antimeasles [[immunoglobulins]] (antibodies) are acquired via the [[placenta]] from the mother during pregnancy may persist to prevent the vaccine viruses from being effective.{{citation needed|date=January 2014}} A second dose is usually given to children between the ages of four and five, to increase rates of immunity. Vaccination rates have been high enough to make measles relatively uncommon. Adverse reactions to vaccination are rare, with fever and pain at the injection site being the most common. Life-threatening adverse reactions occur in less than one per million vaccinations (<0.0001%).<ref name=cubavac >{{cite journal | author = Galindo BM, Concepción D, Galindo MA, Pérez A, Saiz J | title = Vaccine-related adverse events in Cuban children, 1999–2008 | journal = MEDICC Review | volume = 14 | issue = 1 | pages = 38–43 | year = 2012 | pmid = 22334111 | doi = | url = http://www.medicc.org/mediccreview/index.php?issue=19&id=237&a=vahtml | publisher = }}</ref> |

||

In developing countries where measles is highly [[Endemic (epidemiology)|endemic]], [[World Health Organization|WHO]] doctors recommend two doses of [[vaccine]] be given at six and nine months of age. The vaccine should be given whether the child is HIV-infected or not.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Helfand RF, Witte D, Fowlkes A, Garcia P, Yang C, Fudzulani R, Walls L, Bae S, Strebel P, Broadhead R, Bellini WJ, Cutts F | title = Evaluation of the immune response to a 2-dose measles vaccination schedule administered at 6 and 9 months of age to HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected children in Malawi | journal = The Journal of Infectious Diseases | volume = 198 | issue = 10 | pages = 1457–65 | year = 2008 | pmid = 18828743 | doi = 10.1086/592756 }}</ref> The vaccine is less effective in HIV-infected infants than in the general population, but early treatment with antiretroviral drugs can increase its effectiveness.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Ołdakowska A, Marczyńska M | title = Measles vaccination in HIV infected children | journal = Medycyna Wieku Rozwojowego | volume = 12 | issue = 2 Pt 2 | pages = 675–680 | year = 2008 | pmid = 19418943 }}</ref> Measles vaccination programs are often used to deliver other child health interventions, as well, such as bed nets to protect against malaria, antiparasite medicine and vitamin A supplements, and so contribute to the reduction of child deaths from other causes.<ref name="UNICEF">[http://www.unicef.org/media/media_38076.html UNICEF Joint Press Release]</ref> |

In developing countries where measles is highly [[Endemic (epidemiology)|endemic]], [[World Health Organization|WHO]] doctors recommend two doses of [[vaccine]] be given at six and nine months of age. The vaccine should be given whether the child is HIV-infected or not.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Helfand RF, Witte D, Fowlkes A, Garcia P, Yang C, Fudzulani R, Walls L, Bae S, Strebel P, Broadhead R, Bellini WJ, Cutts F | title = Evaluation of the immune response to a 2-dose measles vaccination schedule administered at 6 and 9 months of age to HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected children in Malawi | journal = The Journal of Infectious Diseases | volume = 198 | issue = 10 | pages = 1457–65 | year = 2008 | pmid = 18828743 | doi = 10.1086/592756 }}</ref> The vaccine is less effective in HIV-infected infants than in the general population, but early treatment with antiretroviral drugs can increase its effectiveness.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Ołdakowska A, Marczyńska M | title = Measles vaccination in HIV infected children | journal = Medycyna Wieku Rozwojowego | volume = 12 | issue = 2 Pt 2 | pages = 675–680 | year = 2008 | pmid = 19418943 }}</ref> Measles vaccination programs are often used to deliver other child health interventions, as well, such as bed nets to protect against malaria, antiparasite medicine and vitamin A supplements, and so contribute to the reduction of child deaths from other causes.<ref name="UNICEF">[http://www.unicef.org/media/media_38076.html UNICEF Joint Press Release]</ref> |

||

Unvaccinated populations are at risk for the disease. Traditionally low vaccination rates in northern [[Nigeria]] dropped further in the early 2000s when radical preachers promoted a rumor that polio vaccines were a Western plot to sterilize Muslims and infect them with HIV. The number of cases of measles rose significantly, and hundreds of children died.<ref>{{cite news |title= Measles kills more than 500 children so far in 2005 |publisher=IRIN |date=2005-03-21 |url=http://www.irinnews.org/Report.aspx?ReportId=53506 |accessdate=2007-08-13}}</ref> This could also have had to do with the aforementioned other health-promoting measures often given with the vaccine. |

|||

Claims of a connection between the MMR vaccine and autism were raised in a 1998 paper in ''[[The Lancet]]'', a respected British [[medical journal]].<ref>{{cite journal | author = Wakefield AJ, Murch SH, Anthony A, Linnell J, Casson DM, Malik M, Berelowitz M, Dhillon AP, Thomson MA, Harvey P, Valentine A, Davies SE, Walker-Smith JA | title = Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children | journal = Lancet | volume = 351 | issue = 9103 | pages = 637–41 | year = 1998 | pmid = 9500320 | doi = 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)11096-0 | url = http://briandeer.com/mmr/lancet-paper.htm }}{{Retracted paper|PMID 20137807|intentional=yes}}</ref> Later investigation by ''[[The Sunday Times|Sunday Times]]'' journalist [[Brian Deer]] discovered the lead author of the article, [[Andrew Wakefield]], had multiple undeclared [[conflicts of interest]],<ref>{{cite news |author=Deer B |title=Revealed: MMR research scandal |newspaper=The Sunday Times |location=London |date=2004-02-22 |url=http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/uk/health/article1027603.ece}}<br/> |

|||

{{cite web |author=Deer B |title=The Lancet scandal |year=2007 |publisher=BrianDeer.com |url=http://briandeer.com/mmr-lancet.htm}}<br> |

|||

{{cite web |author=Deer B |title=The Wakefield factor |year=2007 |publisher=BrianDeer.com |url=http://briandeer.com/wakefield-deer.htm}}<br> |

|||

{{cite journal |author=Berger A |title=Dispatches. MMR: What They Didn't Tell You |journal=BMJ |volume=329 |issue=7477 |pages=1293 |year=2004 |doi=10.1136/bmj.329.7477.1293 |url=http://www.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/329/7477/1293}}<br> |

|||

{{cite news |author=Deer B |title=MMR doctor Andrew Wakefield fixed data on autism |newspaper=Sunday Times |date=2009-02-08 |url=http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/life_and_style/health/article5683671.ece |location=London}}{{dead link|date=July 2014}}</ref> and had broken other ethical codes. The ''Lancet'' paper was later fully retracted, and Wakefield was found guilty by the [[General Medical Council]] of serious professional misconduct in May 2010, and was struck off the Medical Register, meaning he could no longer practise as a doctor in the UK.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/8695267.stm |title=MMR doctor struck off register |author=Nick Triggle |date=24 May 2010 |publisher=[[BBC Online]] |accessdate=24 May 2010}}</ref> |

|||

The GMC's panel also considered two of Wakefield's colleagues: John Walker-Smith was also found guilty and struck off the Register; Simon Murch "was in error" but acted in good faith, and was cleared.<ref>{{Cite news |url=http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2010/may/24/mmr-doctor-andrew-wakefield-struck-off |newspaper=The Guardian |date=24 May 2010 |title=MMR row doctor Andrew Wakefield struck off register |accessdate=2 May 2012}}</ref> Walker-Smith was later cleared and reinstated after winning an appeal; the appeal court's finding was based on the panel's conduct of the case, and gave no support to the MMR-autism hypothesis, which the official judgement described as lacking support from any respectable body of opinion.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-17283751|title=MMR doctor wins High Court appeal|date=7 March 2012 |publisher=[[BBC Online]] |accessdate=1 May 2012}}</ref> The research was declared fraudulent in 2011 by the ''[[BMJ]]''.<ref name=WakefieldarticleBMJ>{{cite journal | author = Godlee F, Smith J, Marcovitch H | title = Wakefield's article linking MMR vaccine and autism was fraudulent | journal = BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) | volume = 342 | pages = c7452 | year = 2011 | pmid = 21209060 | doi = 10.1136/bmj.c7452 | url = http://www.bmj.com/content/342/bmj.c7452.full }}</ref> [[Evidence-based medicine|Scientific evidence]] provides no support for the hypothesis that MMR plays a role in causing autism.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Rutter M | title = Incidence of autism spectrum disorders: changes over time and their meaning | journal = Acta Paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992) | volume = 94 | issue = 1 | pages = 2–15 | year = 2005 | pmid = 15858952 | doi = 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2005.tb01779.x | authorlink = Michael Rutter }}</ref> |

|||

The autism-related MMR study in Britain caused use of the vaccine to plunge, and measles cases came back: 2007 saw 971 cases in England and Wales, the biggest rise in occurrence in measles cases since records began in 1995.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Torjesen I | title = Disease: a warning from history | journal = The Health Service Journal | pages = 22–4 | date = 2008-04-17 | pmid = 18533314 | url = http://www.hsj.co.uk/insideknowledge/features/2008/03/ingrid_torjesen_on_the_diseases_we_thought_had_gone_away.html }}</ref> A 2005 measles outbreak in [[Indiana]] was attributed to children whose parents refused vaccination,<ref>{{cite journal | author = Parker AA, Staggs W, Dayan GH, Ortega-Sánchez IR, Rota PA, Lowe L, Boardman P, Teclaw R, Graves C, LeBaron CW | title = Implications of a 2005 measles outbreak in Indiana for sustained elimination of measles in the United States | journal = The New England Journal of Medicine | volume = 355 | issue = 5 | pages = 447–55 | year = 2006 | pmid = 16885548 | doi = 10.1056/NEJMoa060775 }}</ref> as was another outbreak in 2008 in [[San Diego]].<ref>{{cite journal | author = Sugerman DE, Barskey AE, Delea MG, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Bi D, Ralston KJ, Rota PA, Waters-Montijo K, Lebaron CW | title = Measles outbreak in a highly vaccinated population, San Diego, 2008: role of the intentionally undervaccinated | journal = Pediatrics | volume = 125 | issue = 4 | pages = 747–755 | year = 2010 | pmid = 20308208 | doi = 10.1542/peds.2009-1653 }}</ref> |

|||

[[Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]] (CDC) reported that the three biggest outbreaks of measles in 2013 were attributed to clusters of unvaccinated people due to their philosophical or religious beliefs. By August, three pockets of outbreak—in New York City, North Carolina, and Texas—contributed to 64% of the 159 cases of measles that occurred in 16 states. Although measles was thought to be eliminated from the United States in 2000,<ref>{{cite news|title=CDC: Vaccine "philosophical differences" driving up U.S. measles rates|author=Jaslow, Ryan|url=http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-204_162-57602677/cdc-vaccine-philosophical-differences-driving-up-u.s-measles-rates/|newspaper=CBS News|date=12 September 2013|accessdate=19 September 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | title = National, State, and Local Area Vaccination Coverage Among Children Aged 19–35 Months—United States, 2012 | journal = MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report | volume = 62 | issue = 36 | pages = 741–743 | date = 13 September 2013 | pmid = 24025755 | url = http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/wk/mm6236.pdf | publisher = U.S. Department of Health and Human Services }}</ref> |

|||

644 cases were reported in 2014. |

|||

[http://www.cdc.gov/measles/cases-outbreaks.html] |

|||

==Treatment== |

==Treatment== |

||

| Line 158: | Line 117: | ||

===Recent outbreaks=== |

===Recent outbreaks=== |

||

{{Main|Measles outbreaks in the 21st century}} |

{{Main|Measles outbreaks in the 21st century}} |

||

| ⚫ | [[File:Hilleman-Walter-Reed.jpeg|thumb|120px|[[Maurice Hilleman]]'s measles vaccine is estimated to prevent 1 million deaths every year.<ref>"[http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A48244-2005Apr12.html Maurice R. Hilleman Dies; Created Vaccines]". ''The Washington Post''. April 13, 2005.</ref>]] |

||

In 2007, a large outbreak in [[Japan]] caused a number of universities and other institutions to close in an attempt to contain the disease.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/tmp-pmv/2007/measjap070601_e.html|title=The Public Health Agency of Canada Travel Advisory |accessdate=2008-05-02}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |first=Justin |last=Norrie |title=Japanese measles epidemic brings campuses to standstill |url=http://www.smh.com.au/news/world/japanese-measles-epidemic-brings-campuses-to-standstill/2007/05/27/1180205052602.html |publisher=The Sydney Morning Herald |date=May 27, 2007 |accessdate=2008-07-10 }}</ref> |

In 2007, a large outbreak in [[Japan]] caused a number of universities and other institutions to close in an attempt to contain the disease.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/tmp-pmv/2007/measjap070601_e.html|title=The Public Health Agency of Canada Travel Advisory |accessdate=2008-05-02}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |first=Justin |last=Norrie |title=Japanese measles epidemic brings campuses to standstill |url=http://www.smh.com.au/news/world/japanese-measles-epidemic-brings-campuses-to-standstill/2007/05/27/1180205052602.html |publisher=The Sydney Morning Herald |date=May 27, 2007 |accessdate=2008-07-10 }}</ref> |

||

| Line 201: | Line 158: | ||

==History== |

==History== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

The [[Antonine Plague]],<ref>[http://www.loyno.edu/~history/journal/1996-7/Smith.html Plague in the Ancient World]</ref> 165–180 AD, also known as the Plague of [[Galen]], who described it, was probably [[smallpox]] or measles. The epidemic may have claimed the life of [[Roman emperor]] [[Lucius Verus]]. Total deaths have been estimated at five million.<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/4381924.stm "Past pandemics that ravaged Europe"], BBC News, November 7, 2005</ref> Estimates of the timing of evolution of measles seem to suggest this plague was something other than measles. The first scientific description of measles and its distinction from smallpox and [[chickenpox]] is credited to the [[Medicine in medieval Islam|Persian]] physician [[Rhazes]] (860–932), who published ''The Book of Smallpox and Measles''.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Harminder S. Dua, Ahmad Muneer Otri|first=Arun D. Singh|year=2008|title=Abu Bakr Razi|journal=British Journal of Ophthalmology|publisher=[[BMJ Group]]|volume=92|page=1324}}</ref> Given what is now known about the evolution of measles, this account is remarkably timely, as recent work that examined the mutation rate of the virus indicates the measles virus emerged from [[rinderpest]] (Cattle Plague) as a [[Zoonosis|zoonotic disease]] between 1100 and 1200 AD, a period that may have been preceded by limited outbreaks involving a virus not yet fully acclimated to humans.<ref name = Furuse2010>{{Cite journal| doi = 10.1186/1743-422X-7-52| issn = 1743-422X| volume = 7| pages = 52| last = Furuse| first = Yuki|author2=Akira Suzuki |author3=Hitoshi Oshitani | title = Origin of measles virus: divergence from rinderpest virus between the 11th and 12th centuries| journal = Virology Journal| accessdate = 2014-09-14| date = 2010-03-04| url = http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2838858/| pmid = 20202190| pmc=2838858 }}</ref> This agrees with the observation that measles requires a susceptible population of >500,000 to sustain an epidemic, a situation that occurred in historic times following the growth of medieval European cities.<ref name = Black1966>{{Cite journal| doi = 10.1016/0022-5193(66)90161-5| issn = 0022-5193| volume = 11| issue = 2| pages = 207–211| last = Black| first = Francis L.| title = Measles endemicity in insular populations: Critical community size and its evolutionary implication| journal = Journal of Theoretical Biology| accessdate = 2014-10-15| date = July 1966| url = http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0022519366901615| pmid=5965486}}</ref> |

The [[Antonine Plague]],<ref>[http://www.loyno.edu/~history/journal/1996-7/Smith.html Plague in the Ancient World]</ref> 165–180 AD, also known as the Plague of [[Galen]], who described it, was probably [[smallpox]] or measles. The epidemic may have claimed the life of [[Roman emperor]] [[Lucius Verus]]. Total deaths have been estimated at five million.<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/4381924.stm "Past pandemics that ravaged Europe"], BBC News, November 7, 2005</ref> Estimates of the timing of evolution of measles seem to suggest this plague was something other than measles. The first scientific description of measles and its distinction from smallpox and [[chickenpox]] is credited to the [[Medicine in medieval Islam|Persian]] physician [[Rhazes]] (860–932), who published ''The Book of Smallpox and Measles''.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Harminder S. Dua, Ahmad Muneer Otri|first=Arun D. Singh|year=2008|title=Abu Bakr Razi|journal=British Journal of Ophthalmology|publisher=[[BMJ Group]]|volume=92|page=1324}}</ref> Given what is now known about the evolution of measles, this account is remarkably timely, as recent work that examined the mutation rate of the virus indicates the measles virus emerged from [[rinderpest]] (Cattle Plague) as a [[Zoonosis|zoonotic disease]] between 1100 and 1200 AD, a period that may have been preceded by limited outbreaks involving a virus not yet fully acclimated to humans.<ref name = Furuse2010>{{Cite journal| doi = 10.1186/1743-422X-7-52| issn = 1743-422X| volume = 7| pages = 52| last = Furuse| first = Yuki|author2=Akira Suzuki |author3=Hitoshi Oshitani | title = Origin of measles virus: divergence from rinderpest virus between the 11th and 12th centuries| journal = Virology Journal| accessdate = 2014-09-14| date = 2010-03-04| url = http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2838858/| pmid = 20202190| pmc=2838858 }}</ref> This agrees with the observation that measles requires a susceptible population of >500,000 to sustain an epidemic, a situation that occurred in historic times following the growth of medieval European cities.<ref name = Black1966>{{Cite journal| doi = 10.1016/0022-5193(66)90161-5| issn = 0022-5193| volume = 11| issue = 2| pages = 207–211| last = Black| first = Francis L.| title = Measles endemicity in insular populations: Critical community size and its evolutionary implication| journal = Journal of Theoretical Biology| accessdate = 2014-10-15| date = July 1966| url = http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0022519366901615| pmid=5965486}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | [[File:Hilleman-Walter-Reed.jpeg|thumb|120px|[[Maurice Hilleman]]'s measles vaccine is estimated to prevent 1 million deaths every year.<ref>"[http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A48244-2005Apr12.html Maurice R. Hilleman Dies; Created Vaccines]". ''The Washington Post''. April 13, 2005.</ref>]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

Measles is an [[endemic disease]], meaning it has been continually present in a community, and many people develop resistance. In populations not exposed to measles, exposure to the new disease can be devastating. In 1529, a measles outbreak in [[Cuba]] killed two-thirds of the natives who had previously survived smallpox. Two years later, measles was responsible for the deaths of half the population of [[Honduras]], and had ravaged [[Mexico]], [[Central America]], and the [[Inca]] civilization.<ref>{{Cite book | first = Joseph Patrick | last = Byrne | title = Encyclopedia of Pestilence, Pandemics, and Plagues: A–M | url = http://books.google.com/books?id=5Pvi-ksuKFIC&pg=PA413&dq#v=onepage&q=&f=false | publisher = ABC-CLIO | year = 2008 | page = 413 | isbn = 0-313-34102-8 }} |

Measles is an [[endemic disease]], meaning it has been continually present in a community, and many people develop resistance. In populations not exposed to measles, exposure to the new disease can be devastating. In 1529, a measles outbreak in [[Cuba]] killed two-thirds of the natives who had previously survived smallpox. Two years later, measles was responsible for the deaths of half the population of [[Honduras]], and had ravaged [[Mexico]], [[Central America]], and the [[Inca]] civilization.<ref>{{Cite book | first = Joseph Patrick | last = Byrne | title = Encyclopedia of Pestilence, Pandemics, and Plagues: A–M | url = http://books.google.com/books?id=5Pvi-ksuKFIC&pg=PA413&dq#v=onepage&q=&f=false | publisher = ABC-CLIO | year = 2008 | page = 413 | isbn = 0-313-34102-8 }} |

||

</ref> |

</ref> |

||

| Line 210: | Line 167: | ||

Between roughly 1855 to 2005 measles has been estimated to have killed about 200 million people worldwide.<ref>[http://birdflubook.com/a.php?id=40&t=p Torrey EF and Yolken RH. 2005. Their bugs are worse than their bite. Washington Post, April 3, p. B01.]</ref> Measles killed 20 percent of [[Hawaii]]'s population in the 1850s.<ref>[http://web.archive.org/web/20090101183418/http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/database/article_display.cfm?HHID=422 Migration and Disease]. ''Digital History.''</ref> In 1875, measles killed over 40,000 [[Fiji]]ans, approximately one-third of the population.<ref>[http://www.fsm.ac.fj/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=114&Itemid=148 Fiji School of Medicine]</ref> In the 19th century, the disease decimated the [[Andamanese]] population.<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/4987406.stm Measles hits rare Andaman tribe]. ''BBC News.'' May 16, 2006.</ref> In 1954, the virus causing the disease was isolated from an 13-year-old boy from the United States, David Edmonston, and adapted and propagated on [[chicken|chick]] [[embryo]] [[tissue culture]].<ref>{{cite journal | title = Live attenuated measles vaccine | journal = EPI Newsletter / C Expanded Program on Immunization in the Americas | volume = 2 | issue = 1 | page = 6 | year = 1980 | pmid = 12314356 }}</ref> To date, 21 strains of the measles virus have been identified.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Rima BK, Earle JA, Yeo RP, Herlihy L, Baczko K, ter Meulen V, Carabaña J, Caballero M, Celma ML, Fernandez-Muñoz R | title = Temporal and geographical distribution of measles virus genotypes | journal = The Journal of General Virology | volume = 76 | issue = 5 | pages = 1173–80 | year = 1995 | pmid = 7730801 | doi = 10.1099/0022-1317-76-5-1173 | url = http://vir.sgmjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=7730801 }}</ref> While at [[Merck & Co.|Merck]], [[Maurice Hilleman]] developed the first successful vaccine.<ref>{{cite book |author=Offit PA |title=Vaccinated: One Man's Quest to Defeat the World's Deadliest Diseases |location=Washington, DC |publisher=Smithsonian |isbn=0-06-122796-X |year=2007 }}</ref> Licensed [[vaccine]]s to prevent the disease became available in 1963.<ref>"[http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00041753.htm Measles Prevention: Recommendations of the Immunization Practices Advisory Committee (ACIP)]". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).</ref> An improved measles vaccine became available in 1968.<ref>[http://www.immunize.org/catg.d/p4209.pdf ''Measles: Questions and Answers,''] [http://www.immunize.org/ Immunization Action Coalition].</ref> |

Between roughly 1855 to 2005 measles has been estimated to have killed about 200 million people worldwide.<ref>[http://birdflubook.com/a.php?id=40&t=p Torrey EF and Yolken RH. 2005. Their bugs are worse than their bite. Washington Post, April 3, p. B01.]</ref> Measles killed 20 percent of [[Hawaii]]'s population in the 1850s.<ref>[http://web.archive.org/web/20090101183418/http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/database/article_display.cfm?HHID=422 Migration and Disease]. ''Digital History.''</ref> In 1875, measles killed over 40,000 [[Fiji]]ans, approximately one-third of the population.<ref>[http://www.fsm.ac.fj/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=114&Itemid=148 Fiji School of Medicine]</ref> In the 19th century, the disease decimated the [[Andamanese]] population.<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/4987406.stm Measles hits rare Andaman tribe]. ''BBC News.'' May 16, 2006.</ref> In 1954, the virus causing the disease was isolated from an 13-year-old boy from the United States, David Edmonston, and adapted and propagated on [[chicken|chick]] [[embryo]] [[tissue culture]].<ref>{{cite journal | title = Live attenuated measles vaccine | journal = EPI Newsletter / C Expanded Program on Immunization in the Americas | volume = 2 | issue = 1 | page = 6 | year = 1980 | pmid = 12314356 }}</ref> To date, 21 strains of the measles virus have been identified.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Rima BK, Earle JA, Yeo RP, Herlihy L, Baczko K, ter Meulen V, Carabaña J, Caballero M, Celma ML, Fernandez-Muñoz R | title = Temporal and geographical distribution of measles virus genotypes | journal = The Journal of General Virology | volume = 76 | issue = 5 | pages = 1173–80 | year = 1995 | pmid = 7730801 | doi = 10.1099/0022-1317-76-5-1173 | url = http://vir.sgmjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=7730801 }}</ref> While at [[Merck & Co.|Merck]], [[Maurice Hilleman]] developed the first successful vaccine.<ref>{{cite book |author=Offit PA |title=Vaccinated: One Man's Quest to Defeat the World's Deadliest Diseases |location=Washington, DC |publisher=Smithsonian |isbn=0-06-122796-X |year=2007 }}</ref> Licensed [[vaccine]]s to prevent the disease became available in 1963.<ref>"[http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00041753.htm Measles Prevention: Recommendations of the Immunization Practices Advisory Committee (ACIP)]". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).</ref> An improved measles vaccine became available in 1968.<ref>[http://www.immunize.org/catg.d/p4209.pdf ''Measles: Questions and Answers,''] [http://www.immunize.org/ Immunization Action Coalition].</ref> |

||

== |

==See also== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

*[[Critical community size]] |

*[[Critical community size]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

*[[Vaccine-naive]] |

*[[Vaccine-naive]] |

||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{Reflist| |

{{Reflist|3}} |

||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

Revision as of 07:07, 2 February 2015

| Measles | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Infectious diseases |

Measles, also known as morbilli, English measles, or rubeola (and not to be confused with rubella or roseola) is a highly contagious viral infection of the respiratory system, immune system, and skin caused by a paramyxovirus of the genus Morbillivirus.[1][2] Symptoms usually develop 7–14 days (average 10–12) after exposure to an infected person and the initial symptoms usually include a high fever (often > 40 °C [104 °F]), Koplik's spots (spots in the mouth, these usually appear 1–2 days prior to the rash and last 3–5 days), malaise, loss of appetite, hacking cough (although this may be the last symptom to appear), runny nose and red eyes.[1][3] After this comes a spot-like rash that covers much of the body.[1] The course of measles, provided there are no complications, such as bacterial infections, usually lasts about 7–10 days.[1]

Measles is an airborne disease that is spread through respiration (contact with fluids from an infected person's nose and mouth, either directly or through aerosol transmission via coughing or sneezing). The virus is highly contagious—90% of people without immunity sharing living space with an infected person will catch it.[4] An asymptomatic incubation period occurs nine to twelve days from initial exposure.[5] The period of infectivity has not been definitively established, some saying it lasts from two to four days prior, until two to five days following the onset of the rash (i.e., four to nine days infectivity in total),[6] whereas others say it lasts from two to four days prior until the complete disappearance of the rash. The rash usually appears between two and three days after the onset of illness.[7]

Signs and symptoms

The classic signs and symptoms of measles include four-day fevers (the 4 D's) and the three C's—cough, coryza (head cold), and conjunctivitis (red eyes)—along with fever and rashes. The fever may reach up to 40 °C (104 °F). Koplik's spots seen inside the mouth are pathognomonic (diagnostic) for measles, but are temporary and therefore rarely seen. Their recognition, before the affected person reaches maximum infectivity, can be used to reduce spread of epidemics.[8]

The characteristic measles rash is classically described as a generalized red maculopapular rash that begins several days after the fever starts. It starts on the back of the ears and, after a few hours, spreads to the head and neck before spreading to cover most of the body, often causing itching. The measles rash appears two to four days after the initial symptoms and lasts for up to eight days. The rash is said to "stain", changing color from red to dark brown, before disappearing.[9]

Complications

Complications with measles are relatively common, ranging from mild complications such as diarrhea to serious complications such as pneumonia (either direct viral pneumonia or secondary bacterial pneumonia),[10] otitis media,[11] acute brain inflammation[12] (and very rarely SSPE—subacute sclerosing panencephalitis),[13] and corneal ulceration (leading to corneal scarring).[14] Complications are usually more severe in adults who catch the virus.[15] The death rate in the 1920s was around 30% for measles pneumonia.[16]

Between 1987 and 2000, the case fatality rate across the United States was three measles-attributable deaths per 1000 cases, or 0.3%.[17] In underdeveloped nations with high rates of malnutrition and poor healthcare, fatality rates have been as high as 28%.[17] In immunocompromised persons (e.g., people with AIDS) the fatality rate is approximately 30%.[18] Risk factors for severe measles and its complications include: malnutrition;[19][20] underlying immunodeficiency;[19] pregnancy;[19][21] and vitamin A deficiency.[19][22]

Cause

Measles is caused by the measles virus, a single-stranded, negative-sense, enveloped RNA virus of the genus Morbillivirus within the family Paramyxoviridae. The virus was first isolated in 1954 by Nobel Laureate John F. Enders and Thomas Peebles, who were careful to point out that the isolations were made from patients who had Koplik's spots.[23] Humans are the natural hosts of the virus; no other animal reservoirs are known to exist. This highly contagious virus is spread by coughing and sneezing via close personal contact or direct contact with secretions. Risk factors for measles virus infection include: immunodeficiency caused by HIV or AIDS,[24] leukemia,[25] alkylating agents, or corticosteroid therapy, regardless of immunization status;[19] travel to areas where measles is endemic or contact with travelers to endemic areas;[19] and the loss of passive, inherited antibodies before the age of routine immunization.[19]

Diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis of measles requires a history of fever of at least three days, with at least one of the three C's (cough, coryza, conjunctivitis). Observation of Koplik's spots is also diagnostic of measles.[8][26][27]

Alternatively, laboratory diagnosis of measles can be done with confirmation of positive measles IgM antibodies[28] or isolation of measles virus RNA from respiratory specimens.[29] For people unable to undergo phlebotomy, saliva can be collected for salivary measles-specific IgA testing.[30] Positive contact with other patients known to have measles adds strong epidemiological evidence to the diagnosis. The contact with any infected person in any way, including semen through sex, saliva, or mucus, can cause infection.[27]

Prevention

In developed countries, children are immunized against measles at 12 months, generally as part of a three-part MMR vaccine (measles, mumps, and rubella). The vaccination is generally not given earlier than this because sufficient antimeasles immunoglobulins (antibodies) are acquired via the placenta from the mother during pregnancy may persist to prevent the vaccine viruses from being effective.[citation needed] A second dose is usually given to children between the ages of four and five, to increase rates of immunity. Vaccination rates have been high enough to make measles relatively uncommon. Adverse reactions to vaccination are rare, with fever and pain at the injection site being the most common. Life-threatening adverse reactions occur in less than one per million vaccinations (<0.0001%).[31]

In developing countries where measles is highly endemic, WHO doctors recommend two doses of vaccine be given at six and nine months of age. The vaccine should be given whether the child is HIV-infected or not.[32] The vaccine is less effective in HIV-infected infants than in the general population, but early treatment with antiretroviral drugs can increase its effectiveness.[33] Measles vaccination programs are often used to deliver other child health interventions, as well, such as bed nets to protect against malaria, antiparasite medicine and vitamin A supplements, and so contribute to the reduction of child deaths from other causes.[34]

Treatment

There is no specific treatment for measles. Most patients with uncomplicated measles will recover with rest and supportive treatment. It is, however, important to seek medical advice if the patient becomes more unwell, as they may be developing complications.

Some patients will develop pneumonia as a sequel to the measles. Other complications include ear infections, bronchitis (either viral bronchitis or secondary bacterial bronchitis), and brain inflammation.[35] Brain inflammation from measles has a mortality rate of 15%. While there is no specific treatment for brain inflammation from measles, antibiotics are required for bacterial pneumonia, sinusitis, and bronchitis that can follow measles.

All other treatment addresses symptoms, with ibuprofen or paracetamol to reduce fever and pain and, if required, a fast-acting bronchodilator for cough. As for aspirin, some research has suggested a correlation between children who take aspirin and the development of Reye syndrome.[36] Some research has shown aspirin may not be the only medication associated with Reye, and even antiemetics have been implicated,[37] with the point being the link between aspirin use in children and Reye's syndrome development is weak at best, if not actually nonexistent.[36][38] Nevertheless, most health authorities still caution against the use of aspirin for any fevers in children under 16.[39][40][41][42]

The use of vitamin A in treatment has been investigated. A systematic review of trials into its use found no significant reduction in overall mortality, but it did reduce mortality in children aged under two years.[43][44][45] A specific drug treatment for measles ERDRP-0519 has shown promising results in animal studies, but has not yet been tested in humans.[46][47][48]

Prognosis

The majority of patients survive measles, though in some cases, complications may occur, which may include bronchitis, and—in about 1 in 100,000 cases[49]—panencephalitis, which is usually fatal.[50] Acute measles encephalitis is another serious risk of measles virus infection. It typically occurs two days to one week after the breakout of the measles exanthem and begins with very high fever, severe headache, convulsions and altered mentation. A patient may become comatose, and death or brain injury may occur.[51]

Epidemiology

Measles is extremely infectious and its continued circulation in a community depends on the generation of susceptible hosts by birth of children. In communities which generate insufficient new hosts the disease will die out. This concept was first recognized in measles by Bartlett in 1957, who referred to the minimum number supporting measles as the critical community size (CCS).[52] Analysis of outbreaks in island communities suggested that the CCS for measles is c. 250,000.[53]

In 2011, the WHO estimated that there were about 158,000 deaths caused by measles. This is down from 630,000 deaths in 1990.[54] In developed countries, death occurs in 1 to 2 cases out of every 1,000 (0.1% - 0.2%).[55] In populations with high levels of malnutrition and a lack of adequate healthcare, mortality can be as high as 10%. In cases with complications, the rate may rise to 20–30%.[56] Increased immunization has led to an estimated 78% drop in measles deaths among UN member states.[57][58] This reduction made up 25% of the decline in mortality in children under five during this period.[citation needed]

| WHO-Region | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2005 | 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African Region | 1,240,993 | 481,204 | 520,102 | 316,224 | 12,125 |

| Region of the Americas | 257,790 | 218,579 | 1,755 | 19 | 3,100 |

| Eastern Mediterranean Region | 341,624 | 59,058 | 38,592 | 15,069 | 2,214 |

| European Region | 851,849 | 234,827 | 37,421 | 37,332 | 2,430 |

| South-East Asia Region | 199,535 | 224,925 | 61,975 | 83,627 | 1,540 |

| Western Pacific Region | 1,319,640 | 155,490 | 176,493 | 128,016 | 34,310 |

| Worldwide | 4,211,431 | 1,374,083 | 836,338 | 580,287 | 55,719 |

Even in countries where vaccination has been introduced, rates may remain high. In Ireland, vaccination was introduced in 1985. There were 99,903 cases that year. Within two years, the number of cases had fallen to 201, but this fall was not sustained. Measles is a leading cause of vaccine-preventable childhood mortality. Worldwide, the fatality rate has been significantly reduced by a vaccination campaign led by partners in the Measles Initiative: the American Red Cross, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the United Nations Foundation, UNICEF and the WHO. Globally, measles fell 60% from an estimated 873,000 deaths in 1999 to 345,000 in 2005.[34] Estimates for 2008 indicate deaths fell further to 164,000 globally, with 77% of the remaining measles deaths in 2008 occurring within the Southeast Asian region.[63]

In 2006–07 there were 12,132 cases in 32 European countries: 85% occurred in five countries: Germany, Italy, Romania, Switzerland and the UK. 80% occurred in children and there were 7 deaths.[64]

Five out of six WHO regions have set goals to eliminate measles, and at the 63rd World Health Assembly in May 2010, delegates agreed a global target of a 95% reduction in measles mortality by 2015 from the level seen in 2000, as well as to move towards eventual eradication. However, no specific global target date for eradication has yet been agreed to as of May 2010.[65][66]

On January 22, 2014, the World Health Organization and the Pan American Health Organization declared and certified Colombia free of the measles while becoming the first Latin American country to abolish the infection within its borders.[67][68]

In Vietnam, in the Measles Epidemic in the beginning of 2014, unto April 19 had 8,500 measles cases, 114 fatalities.[69]

Recent outbreaks

In 2007, a large outbreak in Japan caused a number of universities and other institutions to close in an attempt to contain the disease.[70][71]

Many children in ultra-Orthodox Jewish communities were affected due to low vaccination coverage.[72][73] As of 2008, the disease is endemic in the United Kingdom, with 1,217 cases diagnosed in 2008,[74] and epidemics have been reported in Austria, Italy and Switzerland.[75]

On February 19, 2009, 505 measles cases were reported in twelve provinces in northern Vietnam, with Hanoi accounting for 160 cases.[76] A high rate of complications, including meningitis and encephalitis, has worried health workers,[77] and the U.S. CDC recommended all travelers be immunized against measles.[78]

Beginning in April 2009 there was a large outbreak of measles in Bulgaria, with over 24,000 cases including 24 deaths. From Bulgaria, the strain was carried to Germany, Turkey, Greece, Macedonia, and other European countries.[79]

Beginning in September 2009, Johannesburg, South Africa reported about 48 cases of measles. Soon after the outbreak, the government ordered all children to be vaccinated. Vaccination programs were then initiated in all schools, and parents of young children were advised to have them vaccinated.[80] Many people were not willing to have the vaccination done, as it was believed to be unsafe and ineffective. The Health Department assured the public that their program was indeed safe. Speculation arose as to whether or not new needles were being used.[81] By mid-October, there were at least 940 recorded cases, and four deaths.[82]

In early 2010, there was a serious outbreak of measles in the Philippines with 742 cases, leaving four unvaccinated children dead in the capital city of Manila.[83]

As of May 2011, over 17,000 cases of measles have so far been reported from France between January 2008 and April 2011, including 2 deaths in 2010 and 6 deaths in 2011.[84] Over 7,500 of these cases fell in the first three months of 2011, and Spain, Turkey, Macedonia, and Belgium have been among the other European countries reporting further smaller outbreaks.[85] The French outbreak has been specifically linked to a further outbreak in Quebec in 2011, where 327 cases have been reported between January and June 1, 2011,[86] and the European outbreaks in general have also been implicated in further small outbreaks in the USA, where 40 separate importations from the European region had been reported between January 1 and May 20.[87]

Some experts stated that the persistence of the disease in Europe could be a stumbling block to global eradication. It has proven difficult to vaccinate a sufficient number of children in Europe to eradicate the disease, because of opposition on philosophical or religious grounds, or fears of side-effects, or because some minority groups are hard to reach, or simply because parents forget to have their children vaccinated. Vaccination is not mandatory in some countries in Europe, in contrast to the United States and many Latin American countries, where children must be vaccinated before they enter school.[79]

In March 2013, an epidemic was declared in Swansea, Wales, UK with 1,219 cases and 88 hospitalizations to date.[88] A 25-year-old male had measles at the time of death and died from giant cell pneumonia caused by the disease.[89] There have been growing concerns that the epidemic could spread to London and infect many more people due to poor MMR uptake,[90] prompting the Department of Health to set up a mass vaccination campaign targeted at one million school children throughout England.[91]

In late 2013, it was reported in the Philippines that 6,497 measles cases occurred which resulted in 23 deaths.[92]

In 2014 many unvaccinated US citizens visiting the Philippines, and other countries, contracted measles, resulting in 288 cases being recorded in the United States in the first five months of 2014, a twenty-year high.[93]

In January 2015, it was reported that nineteen people from three states who visited Disneyland or Disney California Adventure between Dec. 15 and Dec. 20 fell ill with measles. Sixteen of the cases were in California, two in Utah, and one in Colorado. Officials in California said that of the 16 cases in the state they have only verified that two were fully vaccinated against the disease. Some were partially vaccinated and at least two were too young to be vaccinated. [94] Between the dates of January 1 and 28, 2015, most of the 84 people who were diagnosed with measles were either infected during their visit to Disneyland or by someone who visited the theme park.[95]

Americas

Indigenous measles was declared to have been eliminated in North, Central, and South America; the last endemic case in the region was reported on November 12, 2002, with only northern Argentina and rural Canada, particularly in Ontario, Quebec, and Alberta, having minor endemic status.[96] Outbreaks are still occurring, however, following importations of measles viruses from other world regions. In June 2006, an outbreak in Boston resulted after a resident became infected in India.[97]

Between January 1 and April 25, 2008, a total of 64 confirmed measles cases were preliminarily reported in the United States to the CDC,[98][99] the most reported by this date for any year since 2001. Of the 64 cases, 54 were associated with importation of measles from other countries into the United States, and 63 of the 64 patients were unvaccinated or had unknown or undocumented vaccination status.[100] By July 9, 2008, a total of 127 cases were reported in 15 states (including 22 in Arizona),[101] making it the largest U.S. outbreak since 1997 (when 138 cases were reported).[102] Most of the cases were acquired outside of the United States and afflicted individuals who had not been vaccinated. By July 30, 2008, the number of cases had grown to 131. Of these, about half involved children whose parents rejected vaccination. The 131 cases occurred in seven different outbreaks. There were no deaths, and 15 hospitalizations. Eleven of the cases had received at least one dose of measles vaccine. Children who were unvaccinated or whose vaccination status was unknown accounted for 122 cases. Some of these were under the age when vaccination is recommended, but in 63 cases, the vaccinations had been refused for religious or philosophical reasons.

In March 2014, there was an outbreak that started in a religious community in British Columbia's Fraser Valley.[103]

History

The Antonine Plague,[104] 165–180 AD, also known as the Plague of Galen, who described it, was probably smallpox or measles. The epidemic may have claimed the life of Roman emperor Lucius Verus. Total deaths have been estimated at five million.[105] Estimates of the timing of evolution of measles seem to suggest this plague was something other than measles. The first scientific description of measles and its distinction from smallpox and chickenpox is credited to the Persian physician Rhazes (860–932), who published The Book of Smallpox and Measles.[106] Given what is now known about the evolution of measles, this account is remarkably timely, as recent work that examined the mutation rate of the virus indicates the measles virus emerged from rinderpest (Cattle Plague) as a zoonotic disease between 1100 and 1200 AD, a period that may have been preceded by limited outbreaks involving a virus not yet fully acclimated to humans.[107] This agrees with the observation that measles requires a susceptible population of >500,000 to sustain an epidemic, a situation that occurred in historic times following the growth of medieval European cities.[108]

Measles is an endemic disease, meaning it has been continually present in a community, and many people develop resistance. In populations not exposed to measles, exposure to the new disease can be devastating. In 1529, a measles outbreak in Cuba killed two-thirds of the natives who had previously survived smallpox. Two years later, measles was responsible for the deaths of half the population of Honduras, and had ravaged Mexico, Central America, and the Inca civilization.[110]

Between roughly 1855 to 2005 measles has been estimated to have killed about 200 million people worldwide.[111] Measles killed 20 percent of Hawaii's population in the 1850s.[112] In 1875, measles killed over 40,000 Fijians, approximately one-third of the population.[113] In the 19th century, the disease decimated the Andamanese population.[114] In 1954, the virus causing the disease was isolated from an 13-year-old boy from the United States, David Edmonston, and adapted and propagated on chick embryo tissue culture.[115] To date, 21 strains of the measles virus have been identified.[116] While at Merck, Maurice Hilleman developed the first successful vaccine.[117] Licensed vaccines to prevent the disease became available in 1963.[118] An improved measles vaccine became available in 1968.[119]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d Chen, SSP; Fennelly, G; Burnett, M; Domachowske, J; Dyne, PL; Elston, DM; DeVore, HK; Krilov, LR; Krusinski, P; Patterson, JW; Sawtelle, S; Taylor, GA; Wells, MJ; Wilkes, G; Windle, ML; Young, GM (31 January 2014). Steele, RW (ed.). "Measles". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Caserta, MT, ed. (September 2013). "Measles". Merck Manual Professional. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ^ Longo, D; Fauci, A; Kasper, D; Hauser, S; Jameson, J; Loscalzo, J (2011). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (18 ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07174889-6.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|trans_title=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Risk of infection East and Southwest Asia (PDF) (Report). Occucare International. May 16, 2012. p. 6.

- ^ Broy C, Williamson N, Morris J (2009). "A RE-emerging Infection?". Southern Medical Journal. 102 (3): 299–300. doi:10.1097/SMJ.0b013e318188b2ca. PMID 19204645.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Measles".

- ^ "Measles".

- ^ a b Baxby D (1997). "Classic Paper: Henry Koplik. The diagnosis of the invasion of measles from a study of the exanthema as it appears on the buccal membrane". Reviews in Medical Virology. 7 (2): 71–4. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1654(199707)7:2<71::AID-RMV185>3.0.CO;2-S. PMID 10398471.

- ^ NHS UK: Symptoms of measles. Last reviewed: 26/01/2010.

- ^ Yasunaga H, Shi Y, Takeuchi M, Horiguchi H, Hashimoto H, Matsuda S, Ohe K (2010). "Measles-related hospitalizations and complications in Japan, 2007-2008". Internal Medicine (Tokyo, Japan). 49 (18): 1965–1970. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.49.3843. PMID 20847499.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gardiner, W. T. (2007). "Otitis Media in Measles". The Journal of Laryngology & Otology. 39 (11): 614. doi:10.1017/S0022215100026712.

- ^ "Measles-induced encephalitis". QJM. Epub ahead of print. 2014. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcu113. PMID 24865261. Retrieved August 27, 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Anlar B (2013). "Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis and chronic viral encephalitis". Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 112: 1183–1189. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-52910-7.00039-8. PMID 23622327.

- ^ Foster A, Sommer A (1987). "Corneal ulceration, measles, and childhood blindness in Tanzania". The British Journal of Ophthalmology. 71 (5): 331–343. doi:10.1136/bjo.71.5.331. PMC 1041162. PMID 3580349.

- ^ Sabella C (2010). "Measles: Not just a childhood rash". Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 77 (3): 207–213. doi:10.3949/ccjm.77a.09123. PMID 20200172.

- ^ Ellison, J.B (1931). "Pneumonia in Measles". 1931 Archives of Disease in Childhood. pp. 37–52. PMC 1975146.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ a b Perry RT, Halsey NA (May 1, 2004). "The Clinical Significance of Measles: A Review". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 189 (S1): S4–16. doi:10.1086/377712. PMID 15106083.

- ^ Sension MG, Quinn TC, Markowitz LE, Linnan MJ, Jones TS, Francis HL, Nzilambi N, Duma MN, Ryder RW (1988). "Measles in hospitalized African children with human immunodeficiency virus". American Journal of Diseases of Children (1960). 142 (12): 1271–2. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1988.02150120025021. PMID 3195521.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Chen S.S.P. (October 3, 2011). Measles (Report). Medscape.

- ^ Polonsky JA, Ronsse A, Ciglenecki I, Rull M, Porten K (2013). "High levels of mortality, malnutrition, and measles, among recently-displaced Somali refugees in Dagahaley camp, Dadaab refugee camp complex, Kenya, 2011". Conflict and Health. 7 (1): 1. doi:10.1186/1752-1505-7-1. PMC 3607918. PMID 23339463.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Kanda E, Yamaguchi K, Hanaoka M, Matsui H, Sago H, Kubo T (2013). "Low titers of measles antibodies in Japanese pregnant women: A single-center study". The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research. 39 (2): 500–503. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0756.2012.01997.x. PMID 22925573.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Vitamin A".

- ^ Enders JF, Peebles TC (1954). "Propagation in tissue culture of cytopathogenic agents from patients with measles". Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine (New York, N.Y.). 86 (2): 277–86. doi:10.3181/00379727-86-21073. PMID 13177653.

- ^ Gowda VK, Sukanya V (2012). "Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome with Subacute Sclerosing Panencephalitis". Pediatric Neurology. 47 (5): 379–381. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2012.06.020. PMID 23044024.

- ^ Breitfeld V, Hashida Y, Sherman FE, Odagiri K, Yunis EJ (1973). "Fatal measles infection in children with leukemia". Laboratory Investigation; A Journal of Technical Methods and Pathology. 28 (3): 279–291. PMID 4348408.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Total Health (May 5, 2010). "Actual Confirmed Measles Cases in UK". totalhealth. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- ^ Helfand RF, Heath JL, Anderson LJ, Maes EF, Guris D, Bellini WJ (1997). "Diagnosis of measles with an IgM capture EIA: The optimal timing of specimen collection after rash onset". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 175 (1): 195–199. doi:10.1093/infdis/175.1.195. PMID 8985220.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Njayou M, Balla A, Kapo E (1991). "Comparison of four techniques of measles diagnosis: Virus isolation, immunofluorescence, immunoperoxidase & ELISA". The Indian Journal of Medical Research. 93: 340–344. PMID 1797639.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Friedman M, Hadari I, Goldstein V, Sarov I (1983). "Virus-specific secretory IgA antibodies as a means of rapid diagnosis of measles and mumps infection". Israel Journal of Medical Sciences. 19 (10): 881–884. PMID 6662670.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Galindo BM, Concepción D, Galindo MA, Pérez A, Saiz J (2012). "Vaccine-related adverse events in Cuban children, 1999–2008". MEDICC Review. 14 (1): 38–43. PMID 22334111.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Helfand RF, Witte D, Fowlkes A, Garcia P, Yang C, Fudzulani R, Walls L, Bae S, Strebel P, Broadhead R, Bellini WJ, Cutts F (2008). "Evaluation of the immune response to a 2-dose measles vaccination schedule administered at 6 and 9 months of age to HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected children in Malawi". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 198 (10): 1457–65. doi:10.1086/592756. PMID 18828743.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ołdakowska A, Marczyńska M (2008). "Measles vaccination in HIV infected children". Medycyna Wieku Rozwojowego. 12 (2 Pt 2): 675–680. PMID 19418943.

- ^ a b UNICEF Joint Press Release

- ^ "Complications of Measles". Centers for Disease Control and Prevnetion (CDC).

- ^ a b Starko KM, Ray CG, Dominguez LB, Stromberg WL, Woodall DF (6 Dec 1980). "Reye's Syndrome and Salicylate Use". Pediatrics. 66 (6): 859–64. PMID 7454476. Retrieved 2011-03-17.

It is postulated that salicylate [taken by school-age children], operating in a dose-dependent manner, possibly potentiated by fever, represents a primary causative agent of Reye's syndrome.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Casteels-Van Daele M, Van Geet C, Wouters C, Eggermont E (April 2000). "Reye syndrome revisited: a descriptive term covering a group of heterogeneous disorders". European Journal of Pediatrics. 159 (9): 641–8. doi:10.1007/PL00008399. PMID 11014461. Retrieved 2011-03-17.

Reye syndrome is a non-specific descriptive term covering a group of heterogeneous disorders. Moreover, not only the use of acetylsalicylic acid but also of antiemetics is statistically significant in Reye syndrome cases. Both facts weaken the validity of the epidemiological surveys suggesting a link with acetylsalicylic acid.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schrör K (2007). "Aspirin and Reye Syndrome: A Review of the Evidence". Paediatric Drugs. 9 (3): 195–204. doi:10.2165/00148581-200709030-00008. PMID 17523700. Retrieved 2011-03-17.

The suggestion of a defined cause-effect relationship between aspirin intake and Reye syndrome in children is not supported by sufficient facts. Clearly, no drug treatment is without side effects. Thus, a balanced view of whether treatment with a certain drug is justified in terms of the benefit/risk ratio is always necessary. Aspirin is no exception.

- ^ Macdonald S (2002). "Aspirin use to be banned in under 16 year olds". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 325 (7371): 988. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7371.988/c. PMC 1169585. PMID 12411346.

Professor Alasdair Breckenridge, said, "There are plenty of analgesic products containing paracetamol and ibuprofen for this age group not associated with Reye's syndrome. There is simply no need to expose those under 16 to the risk—however small."

- ^ "Aspirin and Reye's Syndrome". MHRA. October 2003. Retrieved 2011-03-17.

- ^ "Surgeon General's advisory on the use of salicylates and Reye syndrome". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 31 (22): 289–90. June 1982. PMID 6810083.

- ^ Reye's Syndrome at NINDS "Epidemiologic evidence indicates that aspirin (salicylate) is the major preventable risk factor for Reye's syndrome. The mechanism by which aspirin and other salicylates trigger Reye's syndrome is not completely understood."

- ^ Huiming Y, Chaomin W, Meng M (2005). Yang, Huiming (ed.). "Vitamin A for treating measles in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD001479. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001479.pub3. PMID 16235283.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ D'Souza RM, D'Souza R (2002). "Vitamin A for treating measles in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD001479. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001479. PMID 11869601.

- ^ D'Souza RM, D'Souza R (April 2002). "Vitamin A for preventing secondary infections in children with measles—a systematic review". Journal of Tropical Pediatrics. 48 (2): 72–7. doi:10.1093/tropej/48.2.72. PMID 12022432.

- ^ White LK, Yoon JJ, Lee JK, Sun A, Du Y, Fu H, Snyder JP, Plemper RK (2007). "Nonnucleoside Inhibitor of Measles Virus RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase Complex Activity". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 51 (7): 2293–303. doi:10.1128/AAC.00289-07. PMC 1913224. PMID 17470652.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Krumm SA, Yan D, Hovingh ES, Evers TJ, Enkirch T, Reddy GP, Sun A, Saindane MT, Arrendale RF, Painter G, Liotta DC, Natchus MG, von Messling V, Plemper RK (2014). "An Orally Available, Small-Molecule Polymerase Inhibitor Shows Efficacy Against a Lethal Morbillivirus Infection in a Large Animal Model". Science Translational Medicine. 6 (232): 232ra52. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3008517. PMID 24739760.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Will an anti-viral drug put paid to measles? New Scientist 16 April 2014

- ^ [1] "Sub acute sclerosing panencephalitis"

- ^ [2] "NINDS Subacute Sclerosing Panencephalitis Information Page"

- ^ 14-193b. at The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy Professional Edition

- ^ Bartlett, M.S. (1957). "Measles periodicity and community size". J. Roy. Stat. Soc. Ser. A (120): 48–70.

- ^ Black FL (1966). "Measles endemicity in insular populations; critical community size and its evolutionary implications". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 11 (2): 207–11. doi:10.1016/0022-5193(66)90161-5. PMID 5965486.

- ^ Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Adair T, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY; et al. (Dec 15, 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. PMID 23245604.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Complications of measles". CDC. November 3, 2014. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- ^ Measles, World Health Organization Fact sheet N°286. Retrieved June 28, 2012. Updated February 2014

- ^ "Millennium Development Goals Reports". United Nations. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ "Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), Fact Sheet N°290". WHO. May 2014. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- ^ WHO: Global summary on measles, 2006

- ^ Measles Surveillance Data after WHO, last updated 2014-3-6

- ^ Measles reported cases by WHO in 2014

- ^ Số người chết và mắc bệnh theo quốc gia, last update 2014-4-7 by WHO

- ^ WHO Weekly Epidemiology Record, 4th December 2009 WHO.int

- ^ McNeil, G.C. (January 12, 2009). "Eradication Goal for Measles Is Unlikely, Report Says". New York Times. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ^ "Sixty-third World Health Assembly Agenda provisional agenda item 11.15 Global eradication of measles" (PDF). Retrieved 2 June 2010.

- ^ "Sixty-third World Health Assembly notes from day four". Retrieved 2 June 2010.

- ^ Colombia, libre de sarampión y rubéola - Noticias de Salud, Educación, Turismo, Ciencia, Ecología y Vida de hoy - ELTIEMPO.COM

- ^ Colombia fue declarada libre de sarampión y rubéol | ELESPECTADOR.COM

- ^ "Vietnam minister calls for calm in face of 8,500 measles cases, 114 fatalities | Health | Thanh Nien Daily". Thanhniennews.com. Retrieved 2014-04-19.

- ^ "The Public Health Agency of Canada Travel Advisory". Retrieved 2008-05-02.

- ^ Norrie, Justin (May 27, 2007). "Japanese measles epidemic brings campuses to standstill". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2008-07-10.

- ^ Stein-Zamir C, Zentner G, Abramson N, Shoob H, Aboudy Y, Shulman L, Mendelson E (February 2008). "Measles outbreaks affecting children in Jewish ultra-orthodox communities in Jerusalem". Epidemiology and Infection. 136 (2): 207–14. doi:10.1017/S095026880700845X. PMC 2870804. PMID 17433131.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rotem, Tamar (August 11, 2007). "Current measles outbreak hit ultra-Orthodox the hardest". Haaretz. Retrieved 2008-07-10.

- ^ Batty, David (9 January 2009). "Record number of measles cases sparks fear of epidemic". London: guardian.co.uk. Retrieved January 15, 2009.

- ^ Eurosurveillance—View Article

- ^ "Measles spreads to 12 provinces". Look At Vietnam. 20 February 2009.

- ^ "Measles outbreak hits North Vietnam". Saigon Gia Phong. 4 February 2009.

- ^ AmCham Vietnam | Public Notice: Measles immunization recommendation.

- ^ a b Kupferschmidt K (27 April 2012). "Europe's Embarsssing Problem". Science. 336 (6080): 406–7. doi:10.1126/science.336.6080.406. PMID 22539695.

- ^ "Measles Outbreak In Joburg".

- ^ "Childhood Vaccinations Peak In 2009, But Uneven Distribution Persists".

- ^ "Measles Vaccination 'safe'".

- ^ Chua, P.S. (March 29, 2010). "Measles can be serious". Inquirer Global Nation.

- ^ Département des maladies infectieuses. "Epidémie de rougeole en France. Actualisation des données au 20 mai 2011" (PDF). Institut de veille sanitaire.

- ^ WHO Epidemiological Brief (PDF) (Report). World Health Organization (WHO). May 2011.

- ^ Final report of the provincial outbreak of measles in 2011 (Report). Santé et Services sociaux Québec. March 21, 2012.