History of nursing in the United States: Difference between revisions

→Civil War: details |

→Civil War: cite |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

[[Mary Livermore]],<ref>Wendy Hamand Venet, ''A Strong-minded Woman: The Life of Mary Livermore'' (2005)</ref> [[Mary Ann Bickerdyke]], and Annie Wittenmeyer played leadership roles.<ref>Elizabeth D. Leonard. "Civil War Nurse, Civil War Nursing: Rebecca Usher of Maine," ''Civil War History'' (1995): 41#3 190-207. [http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/civil_war_history/v041/41.3.leonard.html in Project MUSE]</ref> After the war some nurses wrote memoirs of their experiences; examples include Dix, Livermore, [[Sarah Palmer Young]], and [[Sarah Emma Edmonds]].<ref>Mary Gardner Holland, ed. ''Our Army Nurses: Stories from Women in the Civil War'' (2002) [http://www.amazon.com/Our-Army-Nurses-Stories-Women/dp/1889020044/ excerpts]</ref> |

[[Mary Livermore]],<ref>Wendy Hamand Venet, ''A Strong-minded Woman: The Life of Mary Livermore'' (2005)</ref> [[Mary Ann Bickerdyke]], and Annie Wittenmeyer played leadership roles.<ref>Elizabeth D. Leonard. "Civil War Nurse, Civil War Nursing: Rebecca Usher of Maine," ''Civil War History'' (1995): 41#3 190-207. [http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/civil_war_history/v041/41.3.leonard.html in Project MUSE]</ref> After the war some nurses wrote memoirs of their experiences; examples include Dix, Livermore, [[Sarah Palmer Young]], and [[Sarah Emma Edmonds]].<ref>Mary Gardner Holland, ed. ''Our Army Nurses: Stories from Women in the Civil War'' (2002) [http://www.amazon.com/Our-Army-Nurses-Stories-Women/dp/1889020044/ excerpts]</ref> |

||

Several thousand women were just as active in nursing in the Confederacy, but were less well organized and faced severe shortages of supplies and a much weaker system of 150 hospitals. Nursing and vital support services were provided not only by matrons and nurses, but also by local volunteers, slaves, free blacks, and prisoners of war.<ref>Libra R. Hilde, ''Worth a Dozen Men: Women and Nursing in the Civil War South '' (2012) [http://www.amazon.com/Worth-Dozen-Men-Nursing-Divided/dp/0813932122/ excerpt]</ref><ref> for letters from a Catholic nun who was in charge of a Confederate hospital see E. Moore Quinn, "'I have been trying very hard to be powerful "nice"': the correspondence of Sister M. De Sales (Brennan) during the American Civil War," ''Irish Studies Review'' (2010) 18 |

Several thousand women were just as active in nursing in the Confederacy, but were less well organized and faced severe shortages of supplies and a much weaker system of 150 hospitals. Nursing and vital support services were provided not only by matrons and nurses, but also by local volunteers, slaves, free blacks, and prisoners of war.<ref>Libra R. Hilde, ''Worth a Dozen Men: Women and Nursing in the Civil War South '' (2012) [http://www.amazon.com/Worth-Dozen-Men-Nursing-Divided/dp/0813932122/ excerpt]</ref><ref> for letters from a Catholic nun who was in charge of a Confederate hospital see E. Moore Quinn, "'I have been trying very hard to be powerful "nice"': the correspondence of Sister M. De Sales (Brennan) during the American Civil War," ''Irish Studies Review'' (2010) 18#2 pp pp 213-233. </ref><ref>Cheryl A. Wells, "Battle Time: Gender, Modernity, and Confederate Hospitals," ''Journal of Social History'' (2001) 35#2 pp. 409-428 [http://www.jstor.org/stable/3790195 in JSTOR]</ref> |

||

===Postwar=== |

===Postwar=== |

||

Revision as of 10:34, 13 December 2014

The History of nursing in the United States focuses on the professionalization of nursing since the Civil War.

Origins

Civil War

During the Civil War (1861-65), the United States Sanitary Commission, a federal civilian agency, handled most of the medical and nursing care of the Union armies, together with necessary acquisition and transportation of medical supplies. Dorothea Dix, serving as the Commission's Superintendent, was able to convince the medical corps of the value of women working in 350 Commission or Army hospitals.[1] North and South, over 20,000 women volunteered to work in hospitals, usually in nursing care.[2] They assisted surgeons during procedures, gave medicines, supervised the feedings and cleaned the bedding and clothes. They gave good cheer, wrote letters the men dictated, and comforted the dying.[3] A representative nurse was Helen L. Gilson (1835-68) of Chelsea, Massachusetts, who served in Sanitary Commission. She supervised supplies, dressed wounds, and cooked special foods for patients on a limited diet. She worked in hospitals after the battles of Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg. She was a successful administrator, especially at the hospital for black soldiers at City Point, Virginia.[4] The middle class women North and South who volunteered provided vitally needed nursing services and were rewarded with a sense of patriotism and civic duty in addition to opportunity to demonstrate their skills and gain new ones, while receiving wages and sharing the hardships of the men.[5]

Mary Livermore,[6] Mary Ann Bickerdyke, and Annie Wittenmeyer played leadership roles.[7] After the war some nurses wrote memoirs of their experiences; examples include Dix, Livermore, Sarah Palmer Young, and Sarah Emma Edmonds.[8]

Several thousand women were just as active in nursing in the Confederacy, but were less well organized and faced severe shortages of supplies and a much weaker system of 150 hospitals. Nursing and vital support services were provided not only by matrons and nurses, but also by local volunteers, slaves, free blacks, and prisoners of war.[9][10][11]

Postwar

Nursing professionalized rapidly in the late 19th century following the British model as larger hospitals set up nursing schools that attracted ambitious women from middle- and working-class backgrounds. Agnes Elizabeth Jones and Linda Richards established quality nursing schools in the U.S. and Japan. Richards was officially America's first professionally trained nurse, graduating in 1873 from the New England Hospital for Women and Children in Boston

In the early 1900s, the autonomous, nursing-controlled, Nightingale-era schools came to an end. Schools became controlled by hospitals, and formal "book learning" was discouraged in favor of clinical experience. Hospitals used student nurses as cheap labor.

Clara Barton and the American Red Cross

Clara Barton gained fame for her nursing work during the Civil War; admirers hailed her as the 'Angel of the Battlefield".[12] In 1869, during her trip to Geneva, Switzerland, Barton was introduced to the Red Cross and Dr. Appia; who later would invite her to be the representative for the American branch of the Red Cross and even help her find financial beneficiaries for the start of the American Red Cross. She was influenced by Henry Dunant's book A Memory of Solferino, which called for the formation of national societies to provide relief voluntarily on a neutral basis. At the beginning of the Franco-Prussian War, in 1870, she assisted the Grand Duchess of Baden in the preparation of military hospitals, and gave the Red Cross society much aid during the war. At the joint request of the German authorities and the Strasbourg Comité de Secours, she superintended the supplying of work to the poor of Strasbourg in 1871, after the Siege of Paris, and in 1871 had charge of the public distribution of supplies to the destitute people of Paris.[13]

When Barton returned to the United States, she inaugurated a movement to gain recognition for the International Committee of the Red Cross by the United States government.[14] In 1873, she began work on this project. In 1878, she met with President Rutherford B. Hayes, who expressed the opinion of most Americans at that time which was the U.S. would never again face a calamity like the Civil War. Barton finally succeeded during the administration of President Chester Arthur, using the argument that the new American Red Cross could respond to crises other than war such as earthquakes, forest fires, and hurricanes. Barton became President of the American branch of the society, which held its first official meeting in 1881.[15]

The Red Cross helped in the floods on the Ohio river, provided Texas with food and supplies during the famine of 1887 and took workers to Illinois in 1888 after a tornado and that same year to Florida for the yellow fever epidemic. Within days after the Johnstown Flood in 1889, Barton led her team of 50 doctors and nurses in response.[16]

In 1897, responding to the humanitarian crisis in the Ottoman Empire in the aftermath of the Hamidian Massacres, Barton sailed to Constantinople and after long negotiations with Abdul Hamid II, opened the first American International Red Cross headquarters in the heart of Turkey. Barton herself traveled along with five other Red Cross expeditions to the Armenian provinces in the spring of 1896, providing relief and humanitarian aid. The society's role changed with the advent of the Spanish-American War during which it aided refugees and prisoners.[17] Barton's last field operation as President of the American Red Cross was helping victims of the Galveston hurricane in 1900. The operation established an orphanage for children.

As criticism arose of her careless management of the American Red Cross, plus her advancing age, Barton had to resign as president in 1904, at the age of 83. She had been forced out of office by a new generation of all-male scientific-experts who reflected the realistic efficiency of the Progressive Era rather than her idealistic humanitarianism. After resigning, Barton founded the National First Aid Society.[18]

Hospitals

The number of hospitals grew from 149 in 1873 to 4,400 in 1910 (with 420,000 beds)[19] to 6,300 in 1933, primarily because the public trusted hospitals more and could afford more intensive and professional care.[20] Most larger hospitals operated a school of nursing, which provided training to young women, who in turn did much of the staffing on an unpaid basis. The number of active graduate nurses rose rapidly from 51,000 in 1910 to 375,000 in 1940 and 700,000 in 1970.[21]

They were operated by city, state and federal agencies, by churches, by stand-alone non-profits, and by for-profit enterprises run by a local doctor.

Religious hospitals

All the major denominations built hospitals staffed by nurses.

In 1915, the Catholic Church ran 541, staffed primarily by unpaid nuns.[22][23]

The Lutheran and Episcopal churches entered the health field, especially by setting up orders of women, called deaconesses who dedicated themselves to nursing services. The modern deaconess movement began in Germany in 1836. William Passavant in 1849 brought the first four deaconesses to Pittsburgh, in the United States, after visiting Kaiserswerth. They worked at the Pittsburgh Infirmary (now Passavant Hospital).[24]

The American Methodists – the largest Protestant denomination—engaged in large-scale missionary activity in Asia and elsewhere in the world, making medical services a priority as early as the 1850s. Methodists in America took note, and began opening their own charitable institutions such as orphanages and old people's homes after 1860. In the 1880s, Methodists began opening hospitals in the United States, which served people of all religious backgrounds beliefs. By 1895 13 hospitals were in operation in major cities. well [25]

In 1884, U.S. Lutherans, particularly John D. Lankenau, brought seven sisters from Germany to run the German Hospital in Philadelphia.

By 1963, the Lutheran Church in America had centers for deaconess work in Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Omaha.[26]

Public health

In the U.S., the role of public health nurse began in Los Angeles in 1898, by 1924 there were 12,000 public health nurses, half of them in the 100 largest cities. Their average annual salary in larger cities was $1390. In addition, there were thousands of nurses employed by private agencies handling similar work. Public health nurses supervised health issues in the public and parochial schools, to prenatal and infant care, handled communicable diseases and tuberculosis and dealt with an aerial diseases.[27]

In the United States, a representative public health worker was Dr. Sara Josephine Baker who established many programs to help the poor in New York City keep their infants healthy, leading teams of nurses into the crowded neighborhoods of Hell's Kitchen and teaching mothers how to dress, feed, and bathe their babies.

The federal Office of Indian Affairs (OIA) operated a large-scale field nursing program. Field nurses targeted native women for health education, emphasizing personal hygiene and infant care and nutrition.[28]

Military nursing

During the Spanish-American War of 1898, medical conditions in the tropical war zone were dangerous, with yellow fever and malaria endemic and deadly.[29] The United States government called for women to volunteer as nurses. The Daughters of the American Revolution and other organizations helped thousands of women to sign up, but few were professionally trained. Among the latter were 250 Catholic nurses, most of them from the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul.[30] The Army hired female civilian nurses to help with the wounded. Dr. Anita Newcomb McGee was put in charge of selecting contract nurses to work as civilians with the U.S. Army. In all, more than 1,500 women nurses worked as contract nurses during that 1898 conflict.

Professionalization was a dominant theme during the Progressive Era, because it valued expertise and hierarchy over ad-hoc volunteering in the name of civic duty. Congress consequently established the Army Nurse Corps in 1901 and the Navy Nurse Corps in 1908. The Red Cross became a quasi-official federal agency in 1905 and its American Red Cross Nursing Service took upon itself primary responsibility for recruiting and assigning nurses.

In World War I 1917-18 the military recruited 20,000 registered nurses (all women) for military and navy duty in 58 military hospitals; they helped staff 47 ambulance companies that operated on the Western Front. More than 10,000 served overseas, while 5,400 nurses enrolled in the Army's new School of Nursing. Key decisions were made by Jane Delano, director of the Red Cross Nursing Service, Mary Adelaide Nutting, president of the American Federation of Nurses, and Annie Warburton Goodrich, dean of the Army School of Nursing.[31]

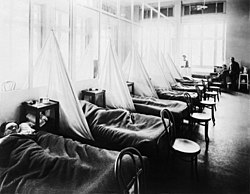

The nurses--all women--were kept well back from the front lines, and although none were killed by enemy action, more than 200 died from disease, especially the massive Spanish flu epidemic. Demobilization reduced the Army and Navy corps to skeleton units designed to be expanded should a new war take place. Eligibility at this time included being female, white, unmarried, volunteer, and a graduate from a civilian nursing school. In 1920, Army Nurse Corps personnel received officer-equivalent ranks and wore Army rank insignia on their uniforms. However, they did not receive equivalent pay and were not considered part of the US Army.

Nursing schools

Sporadic progress was made on several continents, where medical pioneers established formal nursing schools. But even as late as the 1870s, "women working in North American urban hospitals typically were untrained, working class, and accorded lowly status by both the medical profession they supported and society at large". Nursing had the same status in Great Britain and continental Europe before World War I.[32]

Hospital nursing schools in the United States and Canada took the lead in applying Nightingale's model to their training programmers:

standards of classroom and on-the-job training had risen sharply in the 1880s and 1890s, and along with them the expectation of decorous and professional conduct[32]

In late the 1920s, the women's specialties in health care included 294,000 trained nurses, 150,000 untrained nurses, 47,000 midwives, and 550,000 other hospital workers (most of them women).[33]

In recent decades, professionalization has moved nursing degrees out of RN-oriented hospital schools and into community colleges and universities. Specialization has brought numerous journals to broaden the knowledge base of the profession.

American Nurses Association

Initial organizational plans were made for the Nurses Associated Alumnae of the United States of America in 1896 in Manhattan Beach. In February 1897, those plans were ratified in Baltimore at a meeting that coincided with the annual conference of the American Society of Superintendents of Training Schools for Nurses.[34] Isabel Hampton Robb served as the first president. A major early goal of the organization was the enhancement of nursing care for American soldiers.[35]

Other organizations

The United American Nurses (UAN) was an trade union affiliated with the AFL-CIO. Founded in 1999, it only represented registered nurses (RNs). In 2009, UAN merged with the California Nurses Association/National Nurses Organizing Committee and Massachusetts Nurses Association to form National Nurses United.

World War II

As Campbell (1984) shows, the nursing profession was transformed by World War Two. Army and Navy nursing was highly attractive and a larger proportion of nurses volunteered for service higher than any other occupation in American society. The military nurses at first were selected by the civilian men of the Red Cross. But as the nurses rose in rank they took more control and by 1944 were autonomous of the Red Cross. As veterans they took increasing control of the profession through the ANA. [36]

The public image of the nurses was highly favorable during the war, as the simplified by such Hollywood films as "Cry 'Havoc'" which made the selfless nurses heroes under enemy fire. Some nurses were captured by the Japanese,[37] but in practice they were kept out of harm's way, with the great majority stationed on the home front. However, 77 were stationed in the jungles of the Pacific, where their uniform consisted of "khaki slacks, mud, shirts, mud, field shoes, mud, and fatigues."[38][39] The medical services were large operations, with over 600,000 soldiers, and ten enlisted men for every nurse. Nearly all the doctors were men, with women doctors allowed only to examine the WAC.[40]

President Franklin D. Roosevelt hailed the service of nurses in the war effort in his final "Fireside Chat" of January 6, 1945. Expecting heavy casualties in the invasion of Japan, he called for a compulsory draft of nurses. The casualties never happened and there was never a draft of American nurses.[41]

Since 1945

The Nurse Training Act of 1964 transformed the education of nursing, moving the locale from hospitals to universities and community colleges. There was a sharp increase in the number of nurses; not only did the supply increase but more women remained in the profession after their marriage. Salaries went up, as did specialization and the growth of administrative roles for nurses in both the academic and hospital environments.[42] Private duty nursing, once the mainstay for older RNs, became less prevalent. D'Antonio traces the history over six decades of a cohort of nurses who graduated in 1919, going back and forth between paid employment and housework.[43]

See also

Notes

- ^ Thomas J. Brown, Dorothea Dix: New England Reformer (Harvard U.P. 1998)

- ^ Jane E. Schultz, "The Inhospitable Hospital: Gender and Professionalism in Civil War Medicine," Signs (1992) 17#2 pp. 363-392 in JSTOR

- ^ Ann Douglas Wood, "The War within a War: Women Nurses in the Union Army," Civil War History (1972) 18#3

- ^ Edward A. Miller, "Angel of light: Helen L. Gilson, army nurse," Civil War History (1997) 43#1 pp 17-37

- ^ Elizabeth D. Leonard, "Civil war nurse, civil war nursing: Rebecca Usher of Maine," Civil War History (1995) 41#3 pp 190-207

- ^ Wendy Hamand Venet, A Strong-minded Woman: The Life of Mary Livermore (2005)

- ^ Elizabeth D. Leonard. "Civil War Nurse, Civil War Nursing: Rebecca Usher of Maine," Civil War History (1995): 41#3 190-207. in Project MUSE

- ^ Mary Gardner Holland, ed. Our Army Nurses: Stories from Women in the Civil War (2002) excerpts

- ^ Libra R. Hilde, Worth a Dozen Men: Women and Nursing in the Civil War South (2012) excerpt

- ^ for letters from a Catholic nun who was in charge of a Confederate hospital see E. Moore Quinn, "'I have been trying very hard to be powerful "nice"': the correspondence of Sister M. De Sales (Brennan) during the American Civil War," Irish Studies Review (2010) 18#2 pp pp 213-233.

- ^ Cheryl A. Wells, "Battle Time: Gender, Modernity, and Confederate Hospitals," Journal of Social History (2001) 35#2 pp. 409-428 in JSTOR

- ^ Ishbel Ross, Angel of the Battlefield: the life of Clara Barton (1956).

- ^ David Henry Burton, Clara Barton: in the service of humanity (Greenwood, 1995); online

- ^ Epler, Percy Harold (1915). The Life of Clara Barton. Macmillan.

- ^ Marian Moser Jones, The American Red Cross from Clara Barton to the New Deal (2012)

- ^ McCullough, David (1968). The Johnstown Flood. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-39530-8.

- ^ Christine Ardalan, "Clara Barton’s 1898 battles in Cuba: a reexamination of her nursing contributions." Florida Atlantic Comparative Studies Journal 12.1 (2010).

- ^ Burton, Clara Barton: in the service of humanity (Greenwood, 1995)

- ^ U.S. Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States (1976) p 78

- ^ Kalisch and Kalisch, The Advance of American Nursing (1978) p 360

- ^ Historical Statistics of the United States (1976) p 76

- ^ Bernadette McCauley, Who shall take care of our sick?: Roman Catholic sisters and the development of Catholic hospitals in New York City (Johns Hopkins UP, 2005)

- ^ : Barbra Mann Wall, "American Catholic Nursing. An Historical Analysis," Medizinhistorisches Journal (2012) 47#2 pp 160-175.

- ^ See Christ Lutheran Church of Baden

- ^ Wade Crawford Berkeley, History of Methodist Missions: The Methodist Episcopal Church 1845–1939 (1957) pp 82, 192-93 482

- ^ C.D. Naumann, In The Footsteps of Phoebe (Concordia Publishing House, 2009)

- ^ United States Public Health Service, Municipal Health Department Practice for the Year 1923 (Public Health Bulletin # 164, July 1926), pp. 348, 357, 364

- ^ Christin L. Hancock, "Healthy Vocatoons: Field Nursing and the Religious Overtones of Public Health," Journal of Women's History (2001) 23#3 pp 113-137

- ^ Mercedes Graf, "All the Women Were Valiant," Prologue (2014) 46#2 pp 24-34

- ^ Mercedes Graf, "Band Of Angels: Sister Nurses in the Spanish-American War," Prologue (2002) 34#3 pp 196-209. online

- ^ Jennifer Casavant Telford, "The American Nursing Shortage during World War I: The Debate over the Use of Nurses' Aids," Canadian Bulletin of Medical History (2010) 27#1 pp 85-99.

- ^ a b Quinn, Shawna M. "Agnes Warner and the Nursing Sisters of the Great War" (PDF). Goose Lane editions and the New Brunswick Military Heritage Project (2010) ISBN 978-0-86492-633-3. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ^ Harry H. Moore, "Health and Medical Practice" in President's Research Committee on Social Trends, Recent Social Trends in the United States (1933) p1064

- ^ "To Meet Here Next Week". Baltimore American. February 4, 1897. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|1=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Nurses for Peace and War". New York Times. May 7, 1899.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|1=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ D'Ann Campbell, Women at War with America: Private Lives in a Patriotic Era (1984) ch 2

- ^ Elizabeth Norman, We Band of Angels: The Untold Story of American Nurses Trapped on Bataan by the Japanese (1999)

- ^ Mary T. Sarnecky, A history of the U.S. Army Nurse Corps (1999) p. 199 online

- ^ Udin, Zaf. "Nursing Uniforms of the Past and Present". Pulse Uniform.

- ^ Campbell, Women at War with America (1984) ch 2

- ^ see 1945 Radio News : WA4CZD : Free Download & Streaming : Internet Archive

- ^ Joan E. Lynaugh, "Nursing the Great Society: The Impact of the Nurse Training Act of 1964," Nursing History Review (2008) 16#1 pp 13-28.

- ^ Patricia. D'Antonio, "Nurses—and Wives and Mothers: Women and the Latter-day Saints Training School's Class of 1919," Journal of Women's History (2007) 19#3 pp 112-36.

Further reading

- Andrist, Linda C. et al. eds. A History of Nursing Ideas (Sudbury, Mass.: Jones and Bartlett, 2006), 504 pp. 40 essays; focus on professionalization

- Bradshaw, Ann. "Compassion in nursing history." in Providing Compassionate Health Care: Challenges in Policy and Practice (2014) ch 2 pp 21+.

- Bullough, Vern L. and Bonnie Bullough. The Emergence of Modern Nursing (2nd ed. 1972)

- Campbell, D'Ann. Women at War with America: Private Lives in a Patriotic Era (1984) ch 2 on military nurses in World War II

- Dock, Lavinia Lloyd. A Short history of nursing from the earliest times to the present day (1920)full text online; abbreviated version of her four volume A History of Nursing; also vol 3 online

- Choy, Catherine Ceniza. Empire of care: Nursing and migration in Filipino American history (2003)

- D'Antonio, Patricia. American Nursing: A History of Knowledge, Authority, and the Meaning of Work (2010), 272pp excerpt and text search

- Fairman, Julie and Joan E. Lynaugh. Critical Care Nursing: A History (2000) excerpt and text search

- Judd, Deborah. A History of American Nursing: Trends and Eras (2009) 272pp excerpt and text search

- Kalisch, Philip A., and Beatrice J. Kalisch. Advance of American Nursing (3rd ed 1995) ; 4th ed 2003 is titled, American Nursing: A History

- Kaufman, Martin, et al. Dictionary of American Nursing Biography (1988) 196 short biographies by scholars, with further reading for each

- Reverby, Susan M. Ordered to Care: The Dilemma of American Nursing, 1850–1945 (1987) excerpt and text search

- Roberts, Mary M. American nursing: History and interpretation (1954)

- Sarnecky, Mary T. A history of the U.S. Army Nurse Corps (1999) excerpt and text search

- Snodgrass, Mary Ellen. Historical Encyclopedia of Nursing (2004), 354pp; from ancient times to the present

- Sterner, Doris. In and Out of Harm's Way: A History of the Navy Nurse Corps (1998)

- Tomblin, Barbara Brooks. G.I. Nightingales: The Army Nurse Corps in World War II (2004) 272 pages excerpt and text search

- Vuic, Kara D. Officer, Nurse, Woman: The Army Nurse Corps in the Vietnam War (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009)

- Ward, Frances. On Duty: Power, Politics, and the History of Nursing in New Jersey (2009) Excerpt and text search