A Song of Ice and Fire: Difference between revisions

Reverted 1 edit by 24.113.28.45 (talk). (TW) |

|||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

The story of ''A Song of Ice and Fire'' takes place in a fictional world wherein seasons last for years on end. Centuries before the events of the first novel (see [[World of A Song of Ice and Fire#Background|backstory]]), the Seven Kingdoms on the continent [[Westeros]] were united under the [[Targaryen]] dynasty, whereof the last king was killed by feudal lords led by [[Robert Baratheon]], who became king. |

The story of ''A Song of Ice and Fire'' takes place in a fictional world wherein seasons last for years on end. Centuries before the events of the first novel (see [[World of A Song of Ice and Fire#Background|backstory]]), the Seven Kingdoms on the continent [[Westeros]] were united under the [[Targaryen]] dynasty, whereof the last king was killed by feudal lords led by [[Robert Baratheon]], who became king. |

||

The principal story chronicles a power struggle for the "Iron Throne" of Westeros after King Robert's death in the first book, ''[[A Game of Thrones]]''. King Robert's son [[Joffrey Baratheon|Joffrey]] immediately claims the throne with the support of his mother's [[House Lannister|family]]. When Lord Eddard Stark, King Robert's "Hand" (chief advisor) finds out that Joffrey and his siblings are the offspring of incest between siblings Jaime and Cersei Lannister, Eddard is executed for treason and Robert's brothers [[Stannis Baratheon|Stannis]] and [[Renly Baratheon|Renly]] lay separate claim to the throne. Meanwhile, several regions of Westeros attempt self-rule: Eddard Stark's eldest son [[Robb Stark|Robb]] is proclaimed King in the North, while [[Balon Greyjoy]] re-establishes an independent Kingdom in his region, the Iron Islands. This so-called War of the Five Kings is in full progress by the middle of the second book, ''[[A Clash of Kings]]''. |

The principal story chronicles a power struggle for the "Iron Throne" of Westeros after King Robert's death in the first book, ''[[A Game of Thrones]]''. King Robert's son [[Joffrey Baratheon|Joffrey]] immediately claims the throne with the support of his mother's [[House Lannister|family]]. When Lord Eddard Stark, King Robert's "Hand" (chief advisor) finds out that Joffrey and his siblings are the offspring of incest between siblings Jaime and Cersei Lannister, Eddard is executed for treason and Robert's brothers [[Stannis Baratheon|Stannis]] and [[Renly Baratheon|Renly]] lay separate claim to the throne. Meanwhile, several regions of Westeros attempt self-rule: Eddard Stark's eldest son [[Robb Stark|Robb]] is proclaimed King in the North, while [[Balon Greyjoy]] re-establishes an independent Kingdom in his region, the Iron Islands. This so-called War of the Five Kings is in full progress by the middle of the second book, ''[[A Clash of Kings]]''. In the fifth book, ''[[A Dance with Dragons]]'', Joffrey's younger brother Tommen ascends the Iron Throne, with his mother and later his uncle as his regents. |

||

The second story takes place on the northern border of Westeros, where an enormous, eight-thousand-year-old wall of ice defends Westeros from the [[Others (A Song of Ice and Fire)|Others]]. The Wall's sentinels, the Sworn Brotherhood of the [[Night's Watch]], are controlling the human "Free Folk" or "wildlings" beyond the Wall when the first Others appear in ''A Game of Thrones''. The Night's Watch story is told primarily through [[Jon Snow (A Song of Ice and Fire)|Jon Snow]], supposed<ref name="Forbes1"/> [[illegitimacy|bastard son]] of Eddard Stark, as he rises through the ranks. In the third volume, ''[[A Storm of Swords]]'', this story becomes entangled with the civil war. |

The second story takes place on the northern border of Westeros, where an enormous, eight-thousand-year-old wall of ice defends Westeros from the [[Others (A Song of Ice and Fire)|Others]]. The Wall's sentinels, the Sworn Brotherhood of the [[Night's Watch]], are controlling the human "Free Folk" or "wildlings" beyond the Wall when the first Others appear in ''A Game of Thrones''. The Night's Watch story is told primarily through [[Jon Snow (A Song of Ice and Fire)|Jon Snow]], supposed<ref name="Forbes1"/> [[illegitimacy|bastard son]] of Eddard Stark, as he rises through the ranks. In the third volume, ''[[A Storm of Swords]]'', this story becomes entangled with the civil war. |

||

Revision as of 03:58, 23 June 2014

| File:A Game of Thrones Novel Covers.png North American covers for the first five books, illustrated by Larry Rostant | |

| |

| Author | George R. R. Martin |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Genre | Epic fantasy[1] |

| Publisher |

|

| Published | August 1996 – present |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) audiobook |

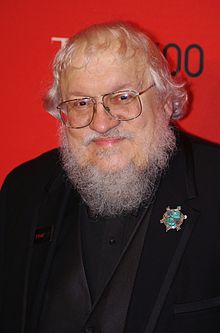

A Song of Ice and Fire is a series of epic fantasy novels written by American novelist and screenwriter George R. R. Martin. Martin began the first volume of the series, A Game of Thrones, in 1991. It was first published in 1996. Martin gradually extended his originally intended trilogy to seven volumes, the fifth of which, A Dance with Dragons, took him five years to write before its publication in 2011; and he has publicly hinted that it might be stretched to an eighth volume. Martin's work on his sixth, The Winds of Winter, is still underway.

The story of A Song of Ice and Fire takes place on the fictional continents Westeros and Essos, with a history of thousands of years. The point of view of each chapter in the story is a limited perspective of an assortment of characters that grows from nine, in the first, to thirty-one by the fifth novel. Three predominant stories interweave: a dynastic war among several families for control of Westeros; the rising threat of the superhuman Others beyond Westeros' northern border; and the ambition of Daenerys Targaryen, the exiled daughter of a king, to assume her ancestral throne.

Martin defied the conventions of the high fantasy genre by drawing upon such historical events as the Wars of the Roses. He drew particular inspiration from the French historical novel series The Accursed Kings by Maurice Druon, set in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, and later wrote the introduction to the English translation of the series, saying: "The Accursed Kings has it all. Believe me, the Starks and the Lannisters have nothing on the Capets and Plantagenets. It is the original game of thrones".[2] A Song of Ice and Fire received favorable critique for its diverse portrayal of women and religion, and praise for favoring realism over magic. The assortment of disparate, subjective, and sometimes inaccurate points of view confront the reader with a variety of perspectives, and the reader may not safely presume that a favorite character will prevail, or even survive. Violence, sexuality and moral ambiguity frequently arise among a thousand named characters.

Though initially published without great acclaim, the books have sold more than 24 million copies in North America alone as of September 2013,[3] and have been translated into more than 20 languages. The fourth and fifth volumes reached the top of The New York Times Best Seller lists upon their releases.[4] Among the many derived works are three prequel novellas in a series and another further historical prequel, the HBO TV series Game of Thrones, a comic book adaptation, and several card, board, and video games.

Plot synopsis

The story of A Song of Ice and Fire takes place in a fictional world wherein seasons last for years on end. Centuries before the events of the first novel (see backstory), the Seven Kingdoms on the continent Westeros were united under the Targaryen dynasty, whereof the last king was killed by feudal lords led by Robert Baratheon, who became king.

The principal story chronicles a power struggle for the "Iron Throne" of Westeros after King Robert's death in the first book, A Game of Thrones. King Robert's son Joffrey immediately claims the throne with the support of his mother's family. When Lord Eddard Stark, King Robert's "Hand" (chief advisor) finds out that Joffrey and his siblings are the offspring of incest between siblings Jaime and Cersei Lannister, Eddard is executed for treason and Robert's brothers Stannis and Renly lay separate claim to the throne. Meanwhile, several regions of Westeros attempt self-rule: Eddard Stark's eldest son Robb is proclaimed King in the North, while Balon Greyjoy re-establishes an independent Kingdom in his region, the Iron Islands. This so-called War of the Five Kings is in full progress by the middle of the second book, A Clash of Kings. In the fifth book, A Dance with Dragons, Joffrey's younger brother Tommen ascends the Iron Throne, with his mother and later his uncle as his regents.

The second story takes place on the northern border of Westeros, where an enormous, eight-thousand-year-old wall of ice defends Westeros from the Others. The Wall's sentinels, the Sworn Brotherhood of the Night's Watch, are controlling the human "Free Folk" or "wildlings" beyond the Wall when the first Others appear in A Game of Thrones. The Night's Watch story is told primarily through Jon Snow, supposed[5] bastard son of Eddard Stark, as he rises through the ranks. In the third volume, A Storm of Swords, this story becomes entangled with the civil war.

The third story is set on an eastern continent named Essos, and follows Daenerys Targaryen, isolated from the others until more POV characters join her in A Dance with Dragons. On Essos, Daenerys rises from a pauper sold into marriage, to a powerful and intelligent ruler. Her rise is aided by the birth of three dragons from dragon eggs given to her as wedding gifts: used initially as symbols, and later as weapons.

Publishing history

Overview

Books in the Ice and Fire series are first published in hardcover and are later re-released as paperback editions. In the UK, Harper Voyager publishes special slipcased editions.[6] The series has also been translated into more than 20 languages.[7] All page totals given below are for the US first editions.

| # | Title | Pages | Chapters | Audio | US release |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A Game of Thrones | 704[8] | 73 | 33h 53m | August 1996[8] |

| 2 | A Clash of Kings | 768[9] | 70 | 37h 17m | February 1999[9] |

| 3 | A Storm of Swords | 992[10] | 82 | 47h 37m | November 2000[10] |

| 4 | A Feast for Crows | 753[11] | 46 | 31h 10m | November 2005[11] |

| 5 | A Dance with Dragons | 1056[12] | 73 | 48h 56m | July 2011[12] |

| 6 | The Winds of Winter | (Forthcoming) | |||

| 7 | A Dream of Spring[13] | (Forthcoming) | |||

First three novels (1991–2000)

George R. R. Martin was already a successful fantasy and sci-fi author and TV writer before writing his A Song of Ice and Fire book series.[14] Martin had published his first short story in 1971 and his first novel in 1977.[15] By the mid-1990s, he had won three Hugo Awards, two Nebulas and other awards for his short fiction.[16] Although his early books were well received within the fantasy fiction community, his readership remained relatively small and Martin took on jobs as a writer in Hollywood in the mid-1980s.[16] He principally worked on the revival of The Twilight Zone throughout 1986 and on Beauty and the Beast until 1990, but he also developed his own TV pilots and wrote feature film scripts. He grew frustrated that his pilots and screenplays were not getting made[16] and that TV-related production limitations like budgets and episode lengths were forcing him to cut characters and trim battle scenes.[17] This pushed Martin back towards writing books, where he did not have to worry about compromising the size of his imagination.[16] Admiring the works of J. R. R. Tolkien in his childhood, he wanted to write an epic fantasy without having any specific ideas.[18]

When Martin was between Hollywood projects in the summer of 1991, he started writing a new science fiction novel called Avalon. After three chapters, he had a vivid idea of a boy seeing a man's beheading and finding direwolves in the snow, which would eventually become the first non-prologue chapter of A Game of Thrones.[19] Putting Avalon aside, Martin finished this chapter in a few days and grew certain that it was part of a longer story.[20] After a few more chapters, Martin perceived his new book as a fantasy story[20] and started making maps and genealogies.[14] However, the writing of this book was interrupted for a few years when Martin returned to Hollywood to produce his TV series Doorways that ABC had ordered but ultimately never aired.[17]

"That just came to me out of nowhere. I was actually at work on a different novel, and suddenly I saw that scene. It didn't belong in the novel I was writing, but it came to me so vividly that I had to sit down and write it, and by the time I did, it led to a second chapter, and the second chapter was the Catelyn chapter where Ned has just come back and she gets the message that the king is dead."

—George R. R. Martin in 2014[21]

In 1994, Martin gave to his agent the first 200 pages and a two-page story projection as part of a planned trilogy with the novels A Dance with Dragons and The Winds of Winter intended to follow. When Martin had still not reached the novel's end at 1400 manuscript pages, he felt the series needed to be four and eventually six books long,[17][22] which he imagined as two linked trilogies of one long story.[23] Martin, who likes ambiguous fiction titles because he feels they enrich the writing, chose A Song of Ice And Fire as the overall series title: Martin saw the struggle of the cold Others and the fiery dragons as one possible meaning for "Ice and Fire", whereas the word "song" had previously appeared in Martin's book titles A Song for Lya and Songs the Dead Men Sing, stemming from his obsessions with songs.[24] Martin also named Robert Frost's 1920 poem "Fire and Ice" and cultural associations such as passion vs. betrayal as possible influences for the series' title.[25]

The revised finished manuscript for A Game of Thrones was 1088 pages long (without the appendices),[26] with the publication following in August 1996.[8] Wheel of Time author Robert Jordan had written a short endorsement for the cover that was influential in ensuring the book's and hence series' early success with fantasy readers.[27] Blood of the Dragon, a pre-release sample novella drawn from Daenerys's chapters, went on to win the 1997 Hugo Award for Best Novella.[28]

The 300 pages removed from the A Game of Thrones manuscript served as the opening of the second book, entitled A Clash of Kings.[22] It was released in February 1999 in the United States,[9] with a manuscript length (without appendices) of 1184 pages.[26] A Clash of Kings was the first book of the Ice and Fire series to make the best-seller lists,[17] reaching 13 on the The New York Times Best Seller list in 1999.[29] After the success of the The Lord of the Rings films, Martin received his first inquiries to the rights of the Ice and Fire series from various producers and filmmakers.[17]

Martin was several months late turning in the third book, A Storm of Swords.[16] The last chapter he had written was about the "Red Wedding", a pivotal scene notable for its violence (see Themes: Violence and death).[30] A Storm of Swords was 1521 pages in manuscript (without appendices),[26] causing problems for many of Martin's publishers around the world. Bantam Books published A Storm of Swords in a single volume in the United States in November 2000,[10] whereas some other-language editions were divided into two, three, or even four volumes.[26] A Storm of Swords debuted at number 12 in the New York Times bestseller list.[28][31]

Bridging the timeline gap (2000–2011)

After A Game of Thrones, A Clash of Kings, and A Storm of Swords, Martin originally intended to write three more books.[16] The fourth book, tentatively titled A Dance with Dragons, was to focus on Daenerys Targaryen's return to Westeros and the associated conflicts.[23] Martin wanted to set this story five years after A Storm of Swords so that the younger characters could grow older and the dragons grow larger.[32] Agreeing with his publishers early on that the new book should be shorter than A Storm of Swords, Martin set out to write the novel closer in length to A Clash of Kings.[26] A long prologue was to establish what had happened in the meantime, initially just as one chapter of Aeron Damphair on the Iron Islands at the Kingsmoot. Since the events on the Iron Islands were to have an impact in the book and could not be told with existing POV characters, Martin eventually introduced three new viewpoints.[33]

In 2001, Martin was still optimistic that the fourth installment might be released in the last quarter of 2002.[24] However, the five-year gap did not work for all characters during writing. On one hand, Martin was unsatisfied with covering the events during the gap solely through flashbacks and internal retrospection. On the other hand, it was implausible to have nothing happening for five years.[32] After working on the book for about a year, Martin realized he needed an additional interim book, which he called A Feast for Crows.[32] The book would pick up the story immediately after the third book, and Martin scrapped the idea of a five-year gap.[24] The material of the written 250-page prologue was mixed in as new viewpoint characters from Dorne and the Iron Islands.[33] These expanded storylines and the resulting story interactions complicated the plot for Martin.[34]

The manuscript length of A Feast For Crows eventually surpassed A Storm of Swords.[32] Martin was reluctant to make the necessary deep cuts to get the book down to publishable length, as that would have compromised the story he had in mind. Printing the book in "microtype on onion skin paper and giving each reader a magnifying glass" was also not an option for him.[26] On the other hand, Martin rejected the publishers' idea of splitting the narrative chronologically into A Feast for Crows, Parts One and Two.[4] Being already late with the book, Martin had not even started writing all characters' stories[35] and also objected to ending the first book without any resolution for its many viewpoint characters as in previous books.[32]

With the characters spread out across the world,[36] a friend suggested that Martin divide the story geographically into two volumes, of which A Feast for Crows would be the first.[4] This approach would give Martin the room to complete his commenced story arcs as he had originally intended,[26] which he still felt was the best approach years later.[36] Martin moved the unfinished characters' stories set in the east (Essos) and north (Winterfell and the Wall) into the next book, A Dance with Dragons,[37] and left A Feast for Crows to cover the events on Westeros, King's Landing, the Riverlands, Dorne, and the Iron Islands.[26] Both books begin immediately after the end of A Storm of Swords,[36] running in parallel instead of sequentially, and involve different casts of characters with only little overlap.[26] Martin split Arya's chapters into both books after having already moved the three other most popular characters (Jon Snow, Tyrion and Daenerys) into A Dance with Dragons.[37]

Upon its release in October 2005 in the UK[38] and November 2005 in the US,[11] A Feast for Crows went straight to the top of the New York Times bestseller list.[39] Among the positive reviewers was Lev Grossman of Time, who dubbed Martin "the American Tolkien".[40] However, fans and critics alike were disappointed with the story split that left the fates of several popular characters unresolved after A Storm of Swords' cliffhanger ending.[41][42] With A Dance with Dragons said to be half-finished,[41] Martin mentioned in the epilogue of A Feast for Crows that the next volume would be released by the next year.[43] However, planned release dates were repeatedly pushed back. Meanwhile, HBO acquired the rights to turn Ice and Fire into a dramatic series in 2007[44] and aired the first of ten episodes covering A Game of Thrones in April 2011.[45]

With around 1600 pages in manuscript length,[1] A Dance with Dragons was eventually published in July 2011 after six years of writing,[17] longer in page count and writing time than any of the preceding four novels.[14][41] The story of A Dance with Dragons catches up and goes beyond A Feast for Crows around two-thirds into the book,[35] but nevertheless covers less story than Martin had intended, omitting at least one planned large battle sequence and leaving several character threads ending in cliff-hangers.[14] Martin attributed the delay mainly to his untangling "the Meereenese knot", which the interviewer understood as "making the chronology and characters mesh up as various threads converged on [Daenerys]".[42] Martin also acknowledged spending too much time on rewriting and perfecting the story, but soundly rejected the theories of his more extravagant critics that he had lost interest in the series or would bide his time to make more money.[41]

Planned novels and future

Martin believes the two last volumes of the series will be big books of 1500 manuscript pages each.[46] The sixth book will be called The Winds of Winter,[47] taking the title of the last book of the originally planned trilogy.[36] By the middle of 2010, Martin had already finished five chapters of The Winds of Winter from the viewpoints of Sansa Stark, Arya Stark, Arianne Martell, and Aeron Damphair, accumulating to around 100 completed pages.[47][48] The Winds of Winter will resolve the Dance with Dragons cliffhangers early on and "will open with the two big battles that [the fifth book] was building up to, the battle in the ice and the battle [...] of Slaver's Bay. And then take it from there."[49] After the publication of A Dance with Dragons, Martin announced he would return to writing in January 2012.[14] He spent the meantime on book tours, conventions, and continued working on his as-yet-unpublished The World of Ice and Fire companion guide and a new Tales of Dunk and Egg novella.[50][51]

In December 2011, Martin posted a chapter from The Winds of Winter from the viewpoint of Theon Greyjoy at his website and promised to include another sample chapter in the paperback version of A Dance with Dragons.[52] International paperbacks had no new sample chapter,[53] whereas the North-American paperback version, originally expected to be released in summer 2012,[49] was pushed back to October 29, 2013.[54] Four hundred pages of the sixth novel have been written as of October 2012, although Martin considers only 200 as "really finished"; the rest needs revising.[25] Martin published another sample chapter from Arianne Martell's POV on his website in January 2013.[55] Martin hopes to finish The Winds of Winter much faster than the fifth book.[41] He gave three years as a realistic estimate for finishing the sixth book at a good pace,[1] but said ultimately the book "will be done when it's done",[36] acknowledging that his publication estimates had been too optimistic in the past.[14] Martin does not intend to separate the characters geographically again but said that "Three years from [2011] when I'm sitting on 1,800 pages of manuscript with no end in sight, who the hell knows".[18]

Displeased with the provisional title A Time for Wolves for the final volume, Martin ultimately announced A Dream of Spring as the title for the seventh book in 2006.[13] Martin is firm about ending the series with the seventh novel "until I decide not to be firm".[14] With his stated goal to tell the story from beginning to end, he will not truncate the story to fit into an arbitrary number of volumes.[30] He knows the ending in broad strokes as well as the future of the main characters,[18] and will finish the series with bittersweet elements where not everyone will live happily ever after.[28] Martin hopes to write an ending similar to The Lord of the Rings that he felt gave the story a satisfying depth and resonance. On the other hand, Martin noted the challenge to avoid a situation like the finale of the TV series Lost, which left some fans disappointed by deviating too far from their own theories and desires.[36]

Early during the development of the TV series, Martin told major plot points to producers David Benioff and D. B. Weiss in case he should die.[18] (The New York Times reported in 2011 that at age 62, Martin was by all accounts in robust health.)[56] Martin is confident he will have published at least The Winds of Winter before the TV series overtakes him.[18] Nevertheless, there is general concern about whether Martin will be able to stay ahead of the show.[57] As a result, head writers Benioff and Weiss learned more future plot points from Martin in 2013 to help them set up the show's new possible seasons. This included the end stories for all the core characters. Deviations from the books' storylines are also being considered, but a two-year show hiatus to wait for new books is not an option for them as the child actors continue to grow and the show's popularity would wane.[58] Martin indicated he would not permit another writer to finish the book series.[41]

Regarding A Song of Ice and Fire as his magnum opus, Martin is certain never to write anything on this scale again and would only return to this fictional universe in the context of stand-alone novels.[33] He prefers to write stories about characters from other Ice and Fire periods of history such as his Tales of Dunk and Egg project, instead of continuing the series directly.[33][59] A possible future side project is a prequel set during Aegon's conquest of Westeros.[60] Martin said he would love to return to writing short stories, novellas, novelettes and stand-alone novels from diverse genres such as science fiction, horror, fantasy, or even a murder mystery. However, he will see if his audience follows him after publishing his next project.[20][27]

Inspiration and writing

Genre

George R. R. Martin believes the most profound influences to be the ones experienced in childhood.[61] Having read H. P. Lovecraft, Robert E. Howard, Robert A. Heinlein, Eric Frank Russell, Andre Norton,[20] Isaac Asimov,[24] Fritz Leiber, and Mervyn Peake[62] in his youth, Martin never categorized these authors' literature into science fiction, fantasy or horror and will write from any genre as a result.[61] Martin classified A Song of Ice and Fire as "epic fantasy"[1] and specifically named Tad Williams as very influential for the writing of the series.[24][62] One of his favorite authors is Jack Vance,[24] although Martin considered the series not particularly Vancean.[23]

"[Martin's Ice and Fire series] was groundbreaking (at least for me) in all kinds of ways. Above all, the books were extremely unpredictable, especially in a genre where readers have come to expect the intensely predictable. [...] A Game of Thrones was profoundly shocking when I first read it, and fundamentally changed my notions about what could be done with epic fantasy."

—Fantasy writer Joe Abercrombie in 2008[63]

The medieval setting has been the traditional background for epic fantasy. However, where historic fiction leaves versed readers knowing the historic outcome,[62] original characters may increase suspense and empathy for the readers.[61] Yet Martin felt historical fiction, particularly when set during the Middle Ages, had an excitement, grittiness and a realness to it that was absent in fantasy with a similar backdrop.[64] Thus, he wanted to combine the realism of historical fiction with the magic appeal of the best fantasies,[65] subduing magic in favor of battles and political intrigue.[16] He also decided to avoid the conventional good versus evil setting typical for the genre, using the fight between Achilles and Hector in Homer's Iliad, where no one stands out as either a hero or a villain, as an example of what he wants to achieve with his books.[66]

Martin is widely credited with broadening the fantasy fiction genre for adult content, including incest, paedophilia and adultery.[41] For The Washington Post's Writing for The Atlantic, Amber Taylor assessed the novels as hard fantasy with vulnerable characters to which readers become emotionally attached.[67] CNN found in 2000 that Martin's mature descriptions were "far more frank than those found in the works of other fantasy authors",[68] although Martin assessed the fantasy genre to have become rougher-edged a decade later and that some writers' work was going beyond the mature themes of his novels.[30]

Writing process

Setting out to write something on an epic scale,[68] Martin projected to write three books of 800 manuscript pages in the very early stages of the series.[62] His original 1990s contract specified one-year deadlines for his previous literary works, but Martin only realized later that his new books were longer and hence required more writing time.[32] In 2000, Martin planned to take 18 months to two years for each volume and projected the last of the planned six books to be released five or six years later.[28] However, with the Ice and Fire series evolving into the biggest and most ambitious story he has ever attempted writing,[37] he still has two more books to write as of 2014. Martin said he needed to be in his own office in Santa Fe, New Mexico to immerse himself in the fictional world and write.[16] Martin still types his fiction on a DOS computer with WordStar 4.0 software.[69] He begins each day at 10 am with rewriting and polishing the previous day's work,[61] and may write all day or struggle writing anything.[16] Excised material and previous old versions are saved to be possibly re-inserted at a later time.[37]

Martin set the Ice and Fire story in a secondary world inspired by Tolkien's writing.[18] Unlike Tolkien, who created entire languages, mythologies, and histories for Middle-earth long before writing The Lord of the Rings, Martin usually starts with a rough sketch of an imaginary world that he improvises into workable fictional setting along the way.[41] He described his writing as coming from a subconscious level in "almost a daydreaming process",[70] and his stories, which have a mythic rather than a scientific core, draw from emotion instead of rationality.[20] Martin employs maps[16] and a cast list topping 60 pages in the fourth volume,[4] but keeps most information in his mind.[1] His imagined backstory remains subject to change until published, and only the novels count as canon.[37] Martin does not intend to publish his private notes after the series is finished.[16]

Martin drew much inspiration from actual history for the series,[61] having several bookcases filled with medieval history for research[71] and visiting historic European landmarks.[34] For an American who speaks only English, the history of England proved the easiest source of medieval history for him, giving the series a British rather than a German or Spanish historic flavor.[72] Ned and Robb Stark, for example, resemble Richard, 3rd Duke of York and his son Edward IV, and Queen Cersei resembles Margaret of Anjou.[73] Martin immersed himself in many diverse medieval topics such as clothing, food, feasting and tournaments, to have the facts at hand if needed during writing.[28] The series was in particular influenced by the Hundred Years' War, the Crusades, the Albigensian Crusade and the Wars of the Roses,[61][71] although Martin refrained from making any direct adaptations.[61]

The story is written to follow principal landmarks with an ultimate destination, but leaves Martin room for improvisation. On occasion, improvised details significantly affected the planned story.[74] By the fourth book, Martin kept more private notes than ever before to keep track of the many subplots,[24] which became so detailed and sprawling by the fifth book as to be unwieldy.[14] Martin's editors, copy editors and fans watch out for accidental mistakes,[24] although some errors have slipped into publication, such as changed eye colors or a switched horse gender.[41]

Narrative structure

| pov character | Game | Clash | Storm | Feast | Dance | (Winds) | Sum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bran Stark | 7 | 7 | 4 | – | 3 | 21 | |

| Catelyn Stark | 11 | 7 | 7 | – | – | 25 | |

| Daenerys Targaryen | 10 | 5 | 6 | – | 10 | 31 | |

| Eddard Stark | 15 | – | – | – | – | 15 | |

| Jon Snow | 9 | 8 | 12 | – | 13 | 42 | |

| Arya Stark | 5 | 10 | 13 | 3 | 2 | ≥1[47] | 33 |

| Tyrion Lannister | 9 | 15 | 11 | – | 12 | ≥2[75] | 47 |

| Sansa Stark | 6 | 8 | 7 | 3 | – | ≥1[47] | 24 |

| Davos Seaworth | – | 3 | 6 | – | 4 | 13 | |

| Theon Greyjoy | – | 6 | – | – | 7 | ≥1[52] | 13 |

| Jaime Lannister | – | – | 9 | 7 | 1 | 17 | |

| Samwell Tarly | – | – | 5 | 5 | – | 10 | |

| Cersei Lannister | – | – | – | 10 | 2 | 12 | |

| Brienne of Tarth | – | – | – | 8 | – | 8 | |

| Aeron Greyjoy | – | – | – | 2 | – | ≥1[48] | 2 |

| Areo Hotah | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Asha Greyjoy | – | – | – | 1 | 3 | 4 | |

| Arys Oakheart | – | – | – | 1 | – | 1 | |

| Victarion Greyjoy | – | – | – | 2 | 2 | ≥1[75] | 4 |

| Arianne Martell | – | – | – | 2 | – | ≥2[47] | 2 |

| Quentyn Martell | – | – | – | – | 4 | 4 | |

| Jon Connington | – | – | – | – | 2 | 2 | |

| Melisandre | – | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | |

| Barristan Selmy | – | – | – | – | 4 | ≥2[54][76] | 4 |

| Prologue/Epilogue | 1/– | 1/– | 1/1 | 1/– | 1/1 | 7 | |

| Total (characters) | 73 (9) | 70 (10) | 82 (12) | 46 (13) | 73 (18) | TBD | 344 (31) |

The books are divided into chapters, each one narrated in the third person limited through the eyes of a point of view character,[41] an approach Martin learned himself as a young journalism student.[77] Each POV character may act from different locations. Beginning with nine viewpoint characters in A Game of Thrones, the number of POV characters grows to a total of 31 in A Dance with Dragons (see table); the short-lived one-time POV characters are mostly restricted to the prologue and epilogue.[28] David Orr of The New York Times noted the story importance of "the Starks (good guys), the Targaryens (at least one good guy, or girl), the Lannisters (conniving), the Greyjoys (mostly conniving), the Baratheons (mixed bag), the Tyrells (unclear) and the Martells (ditto), most of whom are feverishly endeavoring to advance their ambitions and ruin their enemies, preferably unto death".[78] However, as Time's Lev Grossman noted, readers "experience the struggle for Westeros from all sides at once" so that "every fight is both triumph and tragedy [...] and everybody is both hero and villain at the same time".[79]

Modeled on The Lord of the Rings, the Ice and Fire story begins with a tight focus on a small group (with everyone in Winterfell, except Daenerys) and then fans into separate stories. The storylines are to converge again, but finding the turning point in this complex series has been difficult for Martin and slowed down his writing.[36] Depending on the interview, Martin said to have reached the turning point in A Dance with Dragons,[36] or to not quite have reached it yet in the books.[80] The series' structure of multiple POVs and interwoven storylines was inspired by Wild Cards, a multi-authored shared universe book series edited by Martin since 1985.[81] As the sole author, Martin begins each new book with an outline of the chapter order and may write a few successive chapters from a single character's viewpoint instead of working chronologically. The chapters are later rearranged to optimize character intercutting, chronology and suspense.[28]

Influenced by his television and film scripting background, Martin tries to keep readers engrossed by ending each Ice and Fire chapter with a tense or revelational moment, a twist or a cliffhanger, similar to a TV act break.[82] Scriptwriting has also taught him to "cut out the fat and leaving the muscle", which is the final stage of completing a book, a technique that brought the page count in A Dance with Dragons down with almost eighty pages.[83] Dividing the continuous Ice and Fire story into books is much harder for Martin. Each book shall represent a phase of the journey that ends in closure for most characters. A smaller portion of characters is left with clear-cut cliffhangers to make sure readers come back for the next installment, although A Dance with Dragons had more cliffhangers than Martin originally intended.[18][28] Both one-time and regular POV characters are designed to have full character arcs ending in tragedy or triumph,[28] and are written to hold the readers' interest and not be skipped in reading.[62] Main characters are killed off so that the reader will not rely on the hero to come through unscathed and instead feel the character's fear with each page turn.[27]

The unresolved larger narrative arc encourages speculation about future story events.[41] According to Martin, much of the key to Ice and Fire's future lies over a dozen years in the fictional past, of which each volume reveals more.[16] Events planned from the beginning are foreshadowed, although Martin pays attention to not make the story predictable.[80] The viewpoint characters, who serve as unreliable narrators,[36] may clarify or provide different perspectives on past events.[84] What the readers believe to be true may therefore not necessarily be true.[16]

Character development

Regarding the characters as the heart of the story,[85] Martin planned the epic Ice and Fire fantasy to have a large cast of characters and many different settings from the beginning.[36] A Feast for Crows has a 63-page list of characters,[4] with many of the thousands of characters mentioned only in passing[41] or disappearing from view for long stretches.[86] When Martin adds a new family to the ever-growing number of genealogies in the appendices, he devises a secret about the personality or fate of the family members. However, their backstory remains subject to change until written down in the story.[37] Martin drew most character inspiration from history (without directly translating historical figures)[16] and his own experiences, but also from the manners of his friends, acquaintances and people of public interest.[24] Martin aims to "make my characters real and to make them human, characters who have good and bad, noble and selfish [attributes and are] well-mixed in their natures",[28] to which Jeff VanderMeer of the Los Angeles Times remarked that "Martin's devotion to fully inhabiting his characters, for better or worse, creates the unstoppable momentum in his novels and contains an implied criticism of Tolkien's moral simplicity"[87] (see Themes: Moral ambiguity).

Martin deliberately ignored the writing rules to never give two characters a name starting with the same letter.[37] Instead, character names reflect the naming systems in various European family histories, where particular names were associated with specific royal houses and where even the secondary families assigned the same names repeatedly.[37] The Ice and Fire story therefore has children called "Robert" in obeisance to King Robert of House Baratheon, every other generation of the Starks has a "Brandon" in commemoration of Brandon the Builder (of the Wall), and the syllable "Ty" is common in given names of House Lannister.[22] Confident that readers would pay attention, Martin then used techniques as in modern times to discern people with identical given names,[37] such as adding numbers or locations to their given name (e.g. Henry V of England).[22] The family names were designed in association with ethnic groups (see backstory): the First Men in the North of Westeros had very simply descriptive names like Stark and Strong, whereas the descendents of the Andal invaders in the South have more elaborate, undescriptive house names like Lannister or Arryn; the Targaryens and Valyrians from the Eastern continent have the most exotic names with the letter Y.[22]

All characters are designed to speak with their own internal voice to capture their views of the world.[28] The Atlantic pondered whether Martin ultimately intended the readers to sympathize with characters on both sides of the Lannister–Stark feud long before plot developments force them to make their emotional choices.[88] Contrary to most conventional epic fantasies, the Ice and Fire characters are vulnerable so that, according to The Atlantic, the reader "cannot be sure that good shall triumph, which makes those instances where it does all the more exulting."[67] Martin gets emotionally involved in the characters' lives during writing, which makes the chapters with dreadful events sometimes very difficult to write.[28] Seeing the world through the characters' eyes requires a certain amount of empathy with them, including the villains,[61] whom he all loves as if they were his children.[62][85] Martin found that some characters had a mind of their own and took his writing into different directions. He returns to the intended story if it does not work out, but these detours sometimes prove more rewarding for him.[37]

Arya Stark, Tyrion Lannister, Jon Snow and Daenerys Targaryen generate the most feedback from readers.[89] Tyrion is Martin's personal favorite as the grayest of the gray characters, with his cunning and wit making him the most fun to write.[62] Bran Stark is the hardest character to write. As the character most deeply involved in magic, Bran's story needs to be handled carefully within the supernatural aspects of the books. Bran is also the youngest viewpoint character[28] and has to deal with the series' adult themes like grief, loneliness and anger.[82] Martin set out to have the young characters grow up faster between chapters, but as it was implausible for a character to take two months to respond, a finished book represents very little time passed. Martin hoped the planned five-year break would ease the situation and age the children to almost adults in terms of the Seven Kingdoms, but he later dropped the five-year gap (see section Bridging the timeline gap).[18][28]

Themes

This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (March 2013) |

Although modern fantasy may often embrace strangeness, the Ice and Fire series is generally praised for what is generally perceived as a sort of medieval realism.[78] Believing that magic should be used moderately in the epic fantasy genre,[17] George R. R. Martin set out to make the story feel more like historical fiction than contemporary fantasy, with less emphasis on magic and sorcery in favor of battles, political intrigue and the characters.[16] Though the amount of magic has gradually increased throughout the story, the series is still to end with less overt magic than most contemporary fantasies.[28] In Martin's eyes, literary effective magic needs to represent strange and dangerous forces beyond human comprehension,[51] not advanced alien technologies or formulaic spells.[90] As such, the characters understand only the natural aspects of their world, but not the magical elements like the Others.[78]

Since Martin drew on historical sources to build the Ice and Fire world, Damien G. Walter of The Guardian saw a strong resemblance between Westeros and England in the period of the Wars of the Roses.[91] The Atlantic's Adam Serwer regarded A Song of Ice and Fire as "more a story of politics than one of heroism, a story about humanity wrestling with its baser obsessions than fulfilling its glorious potential" where the emergent power struggle stems from the feudal system's repression and not from the fight between good and evil.[88] Martin not only wanted to reflect the frictions of the medieval class structures in the novels, but also explore the consequences of the leaders' decisions, as general goodness does not automatically make competent leaders and vice versa.[65]

A common theme in the fantasy genre is the battle between good and evil,[65] which Martin rejects for not mirroring the real world.[23] Attracted to gray characters instead of orcs and angels,[92] Martin instead endorses Nobel Prize laureate William Faulkner's view that only the human heart in conflict with itself was worth writing about.[65] Just like people's capacity for good and for evil in real life, Martin explores the questions of redemption and character change in the Ice and Fire series.[93] The multiple viewpoint structure allows characters to be explored from many sides so that, unlike many other fantasies, the supposed villains can provide their viewpoint.[68] The reader may then decide about good and evil through the novels' actions and politics.[33]

Although fantasy comes from an imaginative realm, Martin sees an honest necessity to reflect the real world where people die sometimes ugly deaths, even beloved people.[28] Main characters are killed off so that the reader will not expect the supposed hero to come through unscathed and instead feel the character's fear with each page turn.[27] The novels also reflect the substantial death rates in war.[62] The deaths of supernumerary extras or orcs have no major effect on readers, whereas a friend's death has much more emotional impact.[80] Martin prefers a hero's sacrifice to say something profound about human nature.[18]

According to Martin, the fantasy genre rarely focuses on sex and sexuality as much as the Ice and Fire books do,[28] often, in Martin's eyes, treating sexuality in a juvenile way or neglecting it completely.[61] Martin, however, considers sexuality an important driving force in human life that should not be excluded from the narrative.[93] Providing sensory detail for an immersive experience is more important than plot advancement for Martin,[36] who aims to let the readers experience the novels' sex scenes, "whether it's a great transcendent, exciting, mind blowing sex, or whether it's disturbing, twisted, dark sex, or disappointing perfunctory sex."[93] Martin was fascinated by medieval contrasts where knights venerated their ladies with poems and wore their favors in tournaments while their armies mindlessly raped women in wartime.[28] The non-existent concept of adolescence in the Middle Ages served as a model for Daenerys' sexual activity at the age of 13 in the books.[82] The novels also allude to the incestuous practices in the Ptolemaic dynasty of Ancient Egypt to keep their bloodlines pure.[94]

Martin provides a variety of female characters to explore some of the ramifications of the novels being set in a patriarchal society.[80] Writing all characters as human beings with the same basic needs, dreams, and influences,[15] his female characters are to cover the same wide spectrum of human traits as the males.[80] Martin can identify with all point-of-view characters in the writing process despite significant differences to him, be it gender or age.[15] He does not presume to make feminist statements in either way,[80] although the HBO television adaptation sparked a heated critical response about the series' alleged misogyny, the portrayal of women, and the gender distribution of the readership and viewership.[95][96]

Reception

Critical response

Science Fiction Weekly stated in 2000 that "few would dispute that Martin's most monumental achievement to date has been the groundbreaking A Song of Ice and Fire historical fantasy series,"[28] for which reviews have been "orders of magnitude better" than for his previous works, as Martin described to The New Yorker.[41] In 2007, Weird Tales magazine described A Song of Ice and Fire as a "superb fantasy saga" that "raised Martin to a whole new level of success".[20] Shortly before the release of A Dance with Dragons in 2011, Bill Sheehan of The Washington Post was sure that "no work of fantasy has generated such anticipation since Harry Potter's final duel with Voldemort",[86] and Ethan Sacks of Daily News saw the series turning Martin into a darling of literary critics as well as mainstream readers, which was "rare for a fantasy genre that's often dismissed as garbage not fit to line the bottom of a dragon's cage".[52] As Salon.com's Andrew Leonard said, "The success is all the more remarkable because [the series debuted] without mass market publicity or any kind of buzz in the fantasy/SF scene. George R. R. Martin earned his following the hard way, by word of mouth, by hooking his characters into the psyche of his readers to an extent that most writers of fantasy only dream of."[97]

Publishers Weekly noted in 2000 that "Martin may not rival Tolkien or Robert Jordan, but he ranks with such accomplished medievalists of fantasy as Poul Anderson and Gordon Dickson."[10] After the fourth volume came out in 2005, Time's Lev Grossman considered Martin a "major force for evolution in fantasy" and proclaimed him "the American Tolkien", explaining that although Martin was "[not] the best known of America's straight-up fantasy writers" at the time and would "never win a Pulitzer or a National Book Award ... his skill as a crafter of narrative exceeds that of almost any literary novelist writing today".[40] As Grossman said in 2011, the phrase American Tolkien "has stuck to [Martin], as it was meant to",[79] being picked up by the media including The New York Times ("He's much better than that"),[98] the New Yorker,[41] Entertainment Weekly ("an acclaim that borders on fantasy blasphemy"),[14] The Globe and Mail[43] and USA Today.[92] Time magazine named Martin one of the 100 most influential people in the world in 2011,[43] and USA Today named George R.R. Martin their Author of the Year 2011.[99]

According to The Globe and Mail's John Barber, Martin manages simultaneously to master and transcend the genre so that "Critics applaud the depth of his characterizations and lack of cliché in books that are nonetheless replete with dwarves and dragons".[43] Publishers Weekly gave favorable reviews to the first three Ice and Fire novels at their points of release, saying the individual volumes had "superbly developed characters, accomplished prose and sheer bloody-mindedness" (A Game of Thrones),[8] were "notable particularly for the lived-in quality of [their fictional world and] for the comparatively modest role of magic" (A Clash of Kings),[9] and were some "of the more rewarding examples of gigantism in contemporary fantasy" (A Storm of Swords).[10] However, they found that A Feast For Crows as the fourth installment "sorely misses its other half. The slim pickings here are tasty, but in no way satisfying."[11] Their review for A Dance with Dragons repeated points of criticism for the fourth volume and said that although "The new volume has a similar feel to Feast", "Martin keeps it fresh by focusing on popular characters [who were] notably absent from the previous book."[12]

According to the Los Angeles Times, "Martin's brilliance in evoking atmosphere through description is an enduring hallmark of his fiction, the settings much more than just props on a painted stage", and the novels captivate readers with "complex storylines, fascinating characters, great dialogue, perfect pacing, and the willingness to kill off even his major characters".[87] CNN remarked that "the story weaves through differing points of view in a skillful mix of observation, narration and well-crafted dialogue that illuminates both character and plot with fascinating style",[68] and David Orr of The New York Times found that "All of his hundreds of characters have grace notes of history and personality that advance a plot line. Every town has an elaborately recalled series of triumphs and troubles."[78] Salon.com's Andrew Leonard "couldn't stop reading Martin because my desire to know what was going to happen combined with my absolute inability to guess what would happen and left me helpless before his sorcery. At the end, I felt shaken and exhausted."[100] The Christian Science Monitor advised to read the novels with an A Song of Ice and Fire encyclopedia at hand to "catch all the layered, subtle hints and details that [Martin] leaves throughout his books. If you pay attention, you will be rewarded and questions will be answered."[101]

Among the most critical voices were Sam Jordison and Michael Hann, both of The Guardian. Jordison detailed his misgivings about A Game of Thrones in a 2009 review and summarized "It's daft. It's unsophisticated. It's cartoonish. And yet, I couldn't stop reading .... Archaic absurdity aside, Martin's writing is excellent. His dialogue is snappy and frequently funny. His descriptive prose is immediate and atmospheric, especially when it comes to building a sense of deliciously dark foreboding [of the long impending winter]."[102] Hann did not see the novels stand out from the general fantasy genre despite Martin's alterations to fantasy convention, although he rediscovered his childhood's views "That when things are, on the whole, pretty crappy [in the real world], it's a deep joy to dive headfirst into something so completely immersive, something from which there is no need to surface from hours at a time. And if that immersion involves dragons, magic, wraiths from beyond death, shapeshifting wolves and banished princes, so be it."[103]

Sales

The reported overall sales figures of the A Song of Ice and Fire series vary. The New Yorker said in April 2011 (before the publication of A Dance with Dragons) that more than 15 million Ice and Fire books had been sold worldwide,[41] a figure repeated by The Globe and Mail in July 2011.[43] Reuters reported in September 2013 that the books including print, digital and audio versions have sold more than 24 million copies in North America.[3] The Wall Street Journal reported more than six million sold copies in North America by May 2011.[105] USA Today reported 8.5 million copies in print and digital overall in July 2011,[106] and over 12 million sold copies in print in December 2011.[99] The series has been translated into more than 20 languages;[7] USA Today reported the fifth book to be translated into over 40 languages.[92] Forbes estimated that Martin was the 12th highest-earning author worldwide in 2011 at $15 million.[107]

Martin's publishers initially expected A Game of Thrones to be a best-seller,[14] but the first installment did not even reach any lower positions in bestseller list.[50] This left Martin unsurprised, as it is "a fool's game to think anything is going to be successful or to count on it".[85] However, the book slowly won the passionate advocacy of independent booksellers and the book's popularity grew by word-of-mouth.[41] The series' popularity skyrocketed in subsequent volumes,[14] with the second and third volume making the The New York Times Best Seller lists in 1999[29] and 2000,[31] respectively. The series gained Martin's old writings new attention, and Martin's American publisher Bantam Spectra was to reprint his out-of-print solo novels.[28]

The fourth installment, A Feast for Crows, was an immediate best-seller at its 2005 release,[14] which for a fantasy novel suggested that Martin's books were attracting mainstream readers.[1] The paperback edition of A Game of Thrones reached its 34th printing in 2010, surpassing the one million mark.[108] HBO's Game of Thrones boosted sales of the book series before the TV series even premiered, with Ice and Fire approaching triple-digit growth in year-on-year sales. Bantam was looking forward to seeing the tie-ins boost sales further,[45] and Martin's British publisher Harper Voyager expected readers to rediscover their other epic fantasy literature.[109] With a reported 4.5 million copies of the first four volumes in print in early 2011,[45] the four volumes re-appeared on the paperback fiction bestseller lists in the second quarter of 2011.[104][110]

At its point of publication in July 2011, A Dance with Dragons was in its sixth print with more than 650,000 hardbacks in print.[111] It also had the highest single and first-day sales of any new fiction title published in 2011 at that point, with 170,000 hardcovers, 110,000 e-books, and 18,000 audio books reportedly sold on the first day.[106] A Dance with Dragons reached the top of The New York Times bestseller list.[4] Unlike most other big titles, the fifth volume sold more physical than digital copies early on,[56] but nevertheless, Martin became the tenth author to sell 1 million Amazon Kindle e-books.[112] All five volumes and the four-volume boxed set were among the top 100 best-selling books in the United States in 2011 and 2012.[113]

Fandom

During the 1980s and early 1990s, Martin's novels had slowly earned him a reputation in science fiction circles,[114] although he said to only have received a few fans' letters a year in the pre-internet days.[61] The publication of A Game of Thrones caused Martin's following to grow, with fan sites springing up and a Trekkie-like society of followers evolving that meet regularly.[114] Westeros.org, one of the main Ice and Fire fansites with about seventeen thousand registered members as of 2011, was established in 1999 by a Swedish-based fan of Cuban-American descent, Elio M. García, Jr., and his girlfriend; their involvement with Martin's work has now become semi-professional.[41] The Brotherhood Without Banners, an unofficial fan club operating globally, was formed in 2001. Martin counts their founders and other longtime members among his good friends.[41]

Martin runs an official website[4] and administers a lively blog with the assistance of Ty Franck.[41] He also interacts with fandom by answering emails and letters, although he stated in 2005 that their sheer numbers might leave them unanswered for years.[61] Since there are different types of conventions nowadays, he tends to go to three or four science-fiction conventions a year simply to go back to his roots and meet friends.[115] He does not read message boards anymore so that his writing will not be influenced by fans foreseeing twists and interpreting characters differently from what he intended.[115]

"After all, as some of you like to point out in your emails, I am sixty years old and fat, and you don't want me to 'pull a Robert Jordan' on you and deny you your book. Okay, I've got the message. You don't want me doing anything except A Song of Ice and Fire. Ever. (Well, maybe it's okay if I take a leak once in a while?)"

—George R. R. Martin on his blog in 2009[116]

While Martin calls the majority of his fans "great", and enjoys interacting with them,[18] some of them turned against him because of the six years it took to release A Dance with Dragons.[41] A movement of disaffected fans called GRRuMblers formed in 2009, creating sites such as Finish the Book, George and Is Winter Coming?.[41][43] When fans' vocal impatience for A Dance with Dragons peaked shortly after, Martin issued a statement called "To My Detractors"[116] on his blog that received media attention.[41][102][117] The New York Times noted that it was not uncommon for Martin to be mobbed at book signings either.[114] The New Yorker called this "an astonishing amount of effort to devote to denouncing the author of books one professes to love. Few contemporary authors can claim to have inspired such passion."[41]

Awards and nominations

- A Game of Thrones (1996) – Locus Award winner,[118] World Fantasy Award[119] and Nebula Award nominee, 1997[120]

- A Clash of Kings (1998) – Locus Award winner,[118] Nebula Award nominee, 1999[120]

- A Storm of Swords (2000) – Locus Award winner,[118] Hugo Award[121] and Nebula Awards nominee, 2001[122]

- A Feast for Crows (2005) – Hugo,[123] Locus,[118] and British Fantasy Awards nominee, 2006[124]

- A Dance with Dragons (2011) – Locus Award winner,[125] Hugo Award[126] and World Fantasy Award nominee, 2012[127]

Derived works

Novellas

Chapter sets of the books were compiled into three novellas that were released between 1996 and 2003 by Asimov's Science Fiction and Dragon:

- Blood of the Dragon (July 1996),[128] taken from the Daenerys chapters in A Game of Thrones.

- Path of the Dragon (December 2000),[129] taken from the Daenerys chapters in A Storm of Swords.

- Arms of the Kraken (March 2003),[130] based on the Iron Islands chapters from A Feast for Crows.

Martin also wrote three novellas set ninety years before the events of the novels. They are known as the Tales of Dunk and Egg after the main protagonists, Ser Duncan the Tall and his squire "Egg", the later King Aegon V Targaryen. The stories have no direct connection to the plot of A Song of Ice and Fire, although both characters are mentioned in A Storm of Swords and A Feast For Crows, respectively. The first two installments, titled The Hedge Knight and The Sworn Sword, were published in the 1998 Legends and 2003 Legends II anthologies.[33] They are also available as graphic novels.[131] The third novella, titled The Mystery Knight, was first published in the 2010 anthology Warriors[132] and is planned to be adapted as a graphic novel as well.[133] Martin intends to release the first three novellas as one collection in 2014.[134] Up to eight further Dunk and Egg installments are planned.[30]

A seventh novella, The Princess and the Queen or, the Blacks and the Greens, appeared in Tor Books's 2013 anthology Dangerous Women.[135] It does not feature Dunk and Egg, but tells the "true (mostly) story of the origins of the Dance of the Dragons", according to Martin.[136] An eighth novella, The Rogue Prince, or, the King's Brother, will appear in the 2014 anthology Rogues.[137] The story will be a prequel to the events of The Princess and the Queen.

TV series

With the popularity of the series growing, HBO optioned A Song of Ice and Fire for a television adaptation in 2007.[44] A pilot episode was produced in late 2009, and a series commitment for nine further episodes was made in March 2010.[138] The series, titled Game of Thrones, premiered in April 2011 to great acclaim and ratings (see Game of Thrones: Reception). HBO picked up the show for a second season covering A Clash of Kings two days later.[139] Shortly after the conclusion of the first season, the show received 13 Emmy Award nominations, including Outstanding Drama Series and Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Drama Series for Peter Dinklage's portrayal of Tyrion Lannister.[140] HBO announced a renewal for a third season in April 2012, ten days after the season 2 premiere.[141] Due to the length of the corresponding book, the third season only covered roughly the first half of A Storm of Swords.[142] Shortly after the season 3 premiere in March 2013, HBO announced that Game of Thrones would be returning for a fourth season, which would cover the second half of A Storm of Swords along with the beginnings of A Feast for Crows and A Dance With Dragons.[143] Game of Thrones was nominated for 15 Emmy Awards for season 3.[144] Two days after the fourth season premiered in April 2014, HBO renewed Game of Thrones for a fifth and sixth season.[145]

Other works

A Song of Ice and Fire spawned an industry of spin-off products. Fantasy Flight Games released a collectible card game, a board game and two collections of artwork inspired by the Ice and Fire series.[146][147] Various roleplaying game products were released by Guardians of Order and Green Ronin.[148][149] Dynamite Entertainment adapted A Game of Thrones into a same-titled monthly comic in 2011.[150] Several video games are available or in production, including A Game of Thrones: Genesis (2011) and Game of Thrones (2012) by Cyanide.[151][152] A Game of Thrones: Genesis received mediocre ratings from critics.[153] A social network game titled Game of Thrones Ascent is in development by Disruptor Beam that will allow players to live the life of a noble during the series' period setting.[154] Random House released an official map book called The Lands of Ice and Fire, which includes old and new maps of the Ice and Fire world.[155] A companion guide entitled The World of Ice and Fire is in development by George R. R. Martin and the Westeros.org owners Elio García and Linda Antonsson.[41] Other licensed products include full-sized weapon reproductions,[156] a range of collectable figures,[157][158] Westeros coinage reproductions,[159] and a large number of gift and collectible items based on the HBO television series.[160]

References

- ^ a b c d e f Flood, Alison (April 13, 2011). "George RR Martin: Barbarians at the gate". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Game of Thrones: The cult French novel that inspired George RR Martin", BBC News, April 4, 2014

- ^ a b Ronald Grover, Lisa Richwine (September 20, 2013). "With swords and suds, 'Game of Thrones' spurs sales for HBO". Reuters. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g Smith, Dinitia (December 12, 2005). "A Fantasy Realm Too Vile For Hobbits". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kain, Erik (April 30, 2012). "'Game of Thrones' Sails into Darker Waters With 'Ghost of Harrenhal'". Forbes. Retrieved May 2, 2012.

- ^ "A Dance with Dragons [Slipcase edition]". harpercollins.co.uk. Retrieved July 14, 2012.

- ^ a b "Gallery of different language editions". georgerrmartin.com. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d "Fiction review: A Game of Thrones". Publishers Weekly. July 29, 1996. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d "Fiction review: A Clash of Kings". Publishers Weekly. February 1, 1999. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e "Fiction review: A Storm of Swords". Publishers Weekly. October 30, 2000. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d "Fiction review: A Feast for Crows: Book Four of A Song of Ice and Fire". Publishers Weekly. October 3, 2005. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "Fiction review: A Dance with Dragons: A Song of Ice and Fire, Book 5". Publishers Weekly. May 30, 2011. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Martin, George R. R. (March 28, 2006). "this, that, and the other thing". grrm.livejournal.com. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Hibberd, James (July 22, 2011). "The Fantasy King". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Harte, Bryant (July 13, 2011). "An Interview With George R. R. Martin, Part II". indigo.ca. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved February 15, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Richards, Linda (January 2001). "January interview: George R.R. Martin". januarymagazine.com. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) (Interview approved by GRRM.) - ^ a b c d e f g Itzkoff, Dave (April 1, 2011). "His Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy: George R. R. Martin Talks Game of Thrones". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 19, 2012. Retrieved February 3, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hibberd, James (July 12, 2011). "EW interview: George R.R. Martin talks A Dance With Dragons". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Gilmore, Mikal (April 23, 2014). "George R.R. Martin: The Rolling Stone Interview". Rolling Stone. Retrieved April 25, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Schweitzer, Darrell (May 24, 2007). "George R.R. Martin on magic vs. science". weirdtalesmagazine.com. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Windolf, Jim (March 14, 2014). "George R.R. Martin Has a Detailed Plan For Keeping the Game of Thrones TV Show From Catching Up To Him". Vanity Fair. Retrieved April 25, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Martin, George R. R. (March 12, 2012). In Conversation With... George R.R. Martin on Game of Thrones Part 1 – TIFF Bell Lightbox. TIFF Bell Lightbox. Event occurs at 4:00 min (publishing history), 15:00 min (names). Retrieved April 1, 2012. Transcript summary available by Ippolito, Toni-Marie (March 13, 2012). "George R. R. Martin talks to fans about the making of Game of Thrones and what inspired his best-selling book series". thelifestylereport.ca. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved March 22, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Gevers, Nick (December 2000). "Sunsets of High Renown – An Interview with George R. R. Martin". infinityplus.co.uk. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) (Interview approved by GRRM.) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Cogan, Eric (January 30, 2002). "George R.R Martin Interview". fantasyonline.net. Archived from the original on August 18, 2004. Retrieved January 21, 2012. (Interview approved by GRRM.)

- ^ a b Guxens, Adrià (October 7, 2012). "George R.R. Martin: "Trying to please everyone is a horrible mistake"". adriasnews.com. Archived from the original on January 23, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Martin, George R. R. (May 29, 2005). "Done". georgerrmartin.com. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved March 6, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Kirschling, Gregory (November 27, 2007). "By George!". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Robinson, Tasha (December 11, 2000). "Interview: George R.R. Martin continues to sing a magical tale of ice and fire". Science Fiction Weekly. 6, No. 50 (190). scifi.com. Archived from the original on June 27, 2001. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

{{cite journal}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; February 23, 2002 suggested (help) - ^ a b "Best sellers: February 21, 1999". The New York Times. February 21, 1999. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved February 6, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Harte, Bryant (July 12, 2011). "An Interview with George R. R. Martin, Part I". indigo.ca. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved February 15, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Best sellers: November 19, 2000". The New York Times. November 19, 2000. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved February 6, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f "George R.R. Martin: The Gray Lords". locusmag.com. November 2005. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f Lodey (2003). "An Interview with George R. R. Martin". GamePro.com. Archived from the original on October 8, 2003. Retrieved February 15, 2012.

- ^ a b Robinson, Tasha (November 7, 2005). "George R.R. Martin dines on fowl words as the Song of Ice and Fire series continues with A Feast for Crows". Science Fiction Weekly. 11, No. 45 (446). scifi.com. Archived from the original on November 26, 2005. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

- ^ a b Flood, Alison (April 14, 2011). "Getting more from George RR Martin". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Brown, Rachael (July 11, 2011). "George R.R. Martin on Sex, Fantasy, and A Dance With Dragons". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Redman, Bridgette (May 2006). "George R.R. Martin Talks Ice and Fire". book.consumerhelpweb.com. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "A Feast for Crows: Book 4 of A Song of Ice and Fire". Amazon.com. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved February 4, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Best sellers: November 27, 2005". The New York Times. November 27, 2005. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved February 6, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Grossman, Lev (November 13, 2005). "Books: The American Tolkien". Time. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Miller, Laura (April 11, 2011). "Just Write It! A fantasy author and his impatient fans". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Poniewozik, James (July 12, 2011). "The Problems of Power: George R.R. Martin's A Dance With Dragons". Time. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f Barber, John (July 11, 2011). "George R.R. Martin: At the top of his Game (of Thrones)". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Fleming, Michael (January 16, 2007). "HBO turns Fire into fantasy series". Variety. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Thielman, Sam (February 25, 2011). "'Thrones' tomes selling big". Variety. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "George R. R. Martin Webchat Transcript". Empire. April 2012. Archived from the original on July 14, 2012. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e Martin, George R. R. (June 27, 2010). "Dancing in Circles". grrm.livejournal.com. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved February 4, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Martin, George R. R. (July 31, 2010). "Dancing". grrm.livejournal.com. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved February 4, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Roberts, Josh (March 26, 2012). "Game of Thrones Exclusive! George R.R. Martin Talks Season Two, The Winds of Winter, and Real-World Influences for A Song of Ice and Fire". smartertravel.com. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved March 27, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Farley, Christopher John (July 8, 2011). "Game of Thrones Author George R.R. Martin Spills the Secrets of A Dance with Dragons". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved February 15, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Pasick, Adam (October 20, 2011). "George R.R. Martin on His Favorite Game of Thrones Actors, and the Butterfly Effect of TV Adaptations". New York. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved February 15, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Sacks, Ethan (December 30, 2011). "George R.R. Martin surprises Song of Ice and Fire fans with free chapter of next book". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "A Dance with Dragons: A Song of Ice and Fire: Book Five". Amazon.com. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved February 9, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Martin, George R. R. (October 29, 2013). "The Dragons Are Here". grrm.livejournal.com. Retrieved April 17, 2014.

- ^ Martin, George R. R. (January 8, 2013). "A Taste of Winter". grrm.livejournal.com. Archived from the original on January 23, 2013. Retrieved January 9, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Bosman, Julie (July 13, 2011). "A Fantasy Book Revives Store Sales". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hibberd, James (June 9, 2013). "'Game of Thrones' team on series future: 'There is a ticking clock' – EXCLUSIVE". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved April 25, 2014.