Ocean: Difference between revisions

808caTFish (talk | contribs) m →Zones and depths: little syntax fix in sub-section 'Zones and depths' |

→Salinity: More on salinity explaining how to calculate it |

||

| Line 218: | Line 218: | ||

===Salinity=== |

===Salinity=== |

||

A zone of rapid salinity increase with depth is called a[[halocline]]. The temperature of maximum density of [[Salinity#Seawater|seawater]] decreases as its salt content increases. Freezing temperature of water decreases with salinity, and boiling temperature of water increases with [[salinity]]. Typical seawater freezes at around -1.9°C at atmospheric pressure. If precipitation exceeds evaporation, as is the case in polar and temperate regions, salinity will be lower. If evaporation exceeds precipitation, as is the case in tropical regions, salinity will be higher. Thus, oceanic waters in polar regions have lower salinity content than oceanic waters in temperate and tropical regions. <ref name="Chester Marine Geochem">{{cite book|last=Chester, Jickells|first=Roy, Tim|title=Marine Geochemistry|date=2012|publisher=Blackwell Publishing|isbn=978-1-118-34907-6}}</ref> |

|||

Salinity can be calculated using the chlorinity, which is a measure of the total mass of halogen ions (includes fluorine, chlorine, bromine, and iodine) in seawater. By international agreement, the following formula is used to determine salinity: |

|||

'''Salinity (in ‰) = 1.80655 x Chlorinity (in ‰)''' |

|||

The average chlorinity is about 19.2‰, and, thus, the average salinity is around 34.7‰ <ref name="Chester Marine Geochem">{{cite book|last=Chester, Jickells|first=Roy, Tim|title=Marine Geochemistry|date=2012|publisher=Blackwell Publishing|isbn=978-1-118-34907-6}}</ref> |

|||

=== Economic value === |

=== Economic value === |

||

Revision as of 01:20, 5 February 2014

| Earth's ocean |

|---|

|

Main five oceans division: Further subdivision: Marginal seas |

An ocean (from Ancient Greek Ὠκεανός (Okeanos); the World Ocean of classical antiquity[1]) is a body of saline water that composes much of a planet's hydrosphere.[2] On Earth, an ocean is one or all of the major divisions of the planet's World Ocean – which are, in descending order of area, the Pacific, Atlantic, Indian, Southern (Antarctic), and Arctic Oceans.[3][4] The word sea is often used interchangeably with "ocean" in American English but, strictly speaking, a sea is a body of saline water (generally a division of the World Ocean) that land partly or fully encloses.[5]

Earth is the only planet that is known to have an ocean (or any large amounts of open liquid water). Saline water covers approximately 72% of the planet's surface (~3.6x108 km2) and is customarily divided into several principal oceans and smaller seas, with the ocean covering approximately 71% of the Earth's surface.[6] The ocean contains 97% of the Earth's water, and oceanographers have stated that only 5% of the World Ocean has been explored.[6] The total volume is approximately 1.3 billion cubic kilometres (310 million cu mi)[7] with an average depth of 3,682 metres (12,080 ft).[8]

The ocean principally comprises Earth's hydrosphere and therefore is integral to all known life, forms part of the carbon cycle, and influences climate and weather patterns. It is the habitat of 230,000 known species, although much of the ocean's depths remain unexplored, and over two million marine species are estimated to exist.[9] The origin of Earth's oceans remains unknown; oceans are believed to have formed in the Hadean period and may have been the impetus for the emergence of life.

Extraterrestrial oceans may be composed of water or other elements and compounds. The only confirmed large stable bodies of extraterrestrial surface liquids are the lakes of Titan, although there is evidence for the existence of oceans elsewhere in the Solar System. Early in their geologic histories, Mars and Venus are theorized to have had large water oceans. The Mars ocean hypothesis suggests that nearly a third of the surface of Mars was once covered by water, and a runaway greenhouse effect may have boiled away the global ocean of Venus. Compounds such as salts and ammonia dissolved in water lower its freezing point, so that water might exist in large quantities in extraterrestrial environments as brine or convecting ice. Unconfirmed oceans are speculated beneath the surface of many dwarf planets and natural satellites; notably, the ocean of Europa is believed to have over twice the water volume of Earth. The Solar System's gas giant planets are also believed to possess liquid atmospheric layers of yet to be confirmed compositions. Oceans may also exist on exoplanets and exomoons, including surface oceans of liquid water within a circumstellar habitable zone. Ocean planets are a hypothetical type of planet with a surface completely covered with liquid.[10][11]

Earth's global ocean

Divisions

Though generally described as several separate oceans, these waters comprise one global, interconnected body of salt water sometimes referred to as the World Ocean or global ocean.[11][12] This concept of a continuous body of water with relatively free interchange among its parts is of fundamental importance to oceanography.[13]

The major oceanic divisions are defined in part by the continents, various archipelagos, and other criteria. See the table below for more information; note that the table is in descending order in terms of size.[11][14]

| Rank | Ocean | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pacific Ocean | Separates Asia and Oceania from the Americas[14] |

| 2 | Atlantic Ocean | Separates the Americas from Eurasia and Africa |

| 3 | Indian Ocean | Washes upon southern Asia and separates Africa and Australia[14][15][16] |

| 4 | Southern Ocean | Sometimes considered an extension of the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian Oceans,[11][17] which encircles Antarctica |

| 5 | Arctic Ocean | Sometimes considered a sea of the Atlantic, which covers much of the Arctic and washes upon northern North America and Eurasia |

The Pacific and Atlantic may be further subdivided by the equator into northern and southern portions. A smaller region of the ocean can be called other names, such as sea, gulf, bay, and strait.

Physical properties

The total mass of the hydrosphere is about 1,400,000,000,000,000,000 metric tons (1.5×1018 short tons) or 1.4×1021 kg, which is about 0.023 percent of the Earth's total mass. Less than 3 percent is freshwater; the rest is saltwater, mostly in the ocean. The area of the World Ocean is 361 million square kilometres (139 million square miles),[18] and its volume is approximately 1.3 billion cubic kilometres (310 million cu mi).[7] This can be thought of as a cube of water with an edge length of 1,111 kilometres (690 mi). Its average depth is 3,790 metres (12,430 ft), and its maximum depth is 10,923 metres (6.787 mi).[18] Nearly half of the world's marine waters are over 3,000 metres (9,800 ft) deep.[12] The vast expanses of deep ocean (anything below 200 metres (660 ft)) cover about 66% of the Earth's surface.[19] This does not include seas not connected to the World Ocean, such as the Caspian Sea.

The bluish color of water is a composite of several contributing agents. Prominent contributors include dissolved organic matter and chlorophyll.[20]

Sailors and other mariners have reported that the ocean often emits a visible glow, or luminescence, which extends for miles at night. In 2005, scientists announced that for the first time, they had obtained photographic evidence of this glow.[21] It is most likely caused by bioluminescence.[22][23][24]

Zones and depths

Oceanographers divide the ocean into different zones by physical and biological conditions. The pelagic zone includes all open ocean and comprises further regions of depth and light abundance. The photic zone falls two-hundred meters below the oceanic surface and is where photosynthesis can occur and therefore the most biodiverse. Plants require photosynthesis: deeper life relies on material sinking from above (see marine snow) or another energy source. Hydrothermal vents are the primary source in what is known as the aphotic zone (depths exceeding 200 m). The pelagic part of the photic zone is known as the epipelagic.

The pelagic part of the aphotic zone comprises regions that descend in vertical order according to temperature. The mesopelagic is the uppermost region. Its lowermost boundary is at a thermocline of 12 °C (54 °F), which, in the tropics generally lies at 700–1,000 metres (2,300–3,300 ft). Next is the bathypelagic lying between 10 and 4 °C (50 and 39 °F), typically between 700–1,000 metres (2,300–3,300 ft) and 2,000–4,000 metres (6,600–13,100 ft) Lying along the top of the abyssal plain is the abyssopelagic, whose lower boundary lies at about 6,000 metres (20,000 ft). The last zone includes the deep oceanic trench, and is known as the hadalpelagic. This lies between 6,000–11,000 metres (20,000–36,000 ft) and is the deepest oceanic zone.

The benthic zones are aphotic and correspond to the three deepest zones of the deep-sea. The bathyal zone covers the continental slope down to about 4,000 metres (13,000 ft). The abyssal zone covers the abyssal plains between 4,000 and 6,000 m. Lastly, the hadal zone corresponds to the hadalpelagic zone, which is found in oceanic trenches. The pelagic zone comprises two subregions: the neritic zone and the oceanic zone. The neritic encompasses the water mass directly above the continental shelves whereas the oceanic zone includes all the completely open water. Whereas the littoral zone covers the region between low and high tide and represents the transitional area between marine and terrestrial conditions. It is also known as the intertidal zone because it is the area where tide level affects the conditions of the region.

The ocean can be divided into three density zones: the surface zone, the pycnocline, and the deep zone. The surface zone, also called the mixed layer, refers to the uppermost density zone of the ocean. Temperature and salinity are relatively constant with depth in this zone due to currents and wave action. The surface zone contains ocean water that is in contact with the atmosphere and within the photic zone. The surface zone has the ocean's least dense water and represents approximately 2% of the total volume of ocean water. The surface zone usually ranges between depths of 500 feet to 3,300 feet below ocean surface, but this can vary a great deal. In some cases, the surface zone can be entirely non-existent. The surface zone is typically thicker in the tropics than in regions of higher latitude. The transition to colder, denser water is more abrupt in the tropics than in regions of higher latitudes. The pycnocline refers to a zone wherein density substantially increases with depth due primarily to decreases in temperature. The pycnocline effectively separates the lower-density surface zone above from the higher-density deep zone below. The pycnocline represents approximately 18% of the total volume of ocean water. The deep zone refers to the lowermost density zone of the ocean. The deep zone usually begins at depths below 3,300 feet in mid-latitudes. The deep zone undergoes negligible changes in water density with depth. The deep zone represents approximately 80% of the total volume of ocean water. The deep zone contains relatively colder and stable water.

If a zone undergoes dramatic changes in temperature with depth, it contains a thermocline. The tropical thermocline is typically deeper than the thermocline at higher latitudes. Polar waters, which receive relatively little solar energy, are not stratified by temperature and generally lack a thermocline since surface water at polar latitudes are nearly as cold as water at greater depths. Below the thermocline, water is very cold, ranging from -1°C to 3°C. Since this deep and cold layer contains the bulk of ocean water, the average temperature of the world ocean is 3.9°C If a zone undergoes dramatic changes in salinity with depth, it contains a halocline. If a zone undergoes a strong, vertical chemistry gradient with depth, it contains a chemocline.

The halocline often coincides with the thermocline, and the combination produces a pronounced pycnocline.

Exploration

Ocean travel by boat dates back to prehistoric times, but only in modern times has extensive underwater travel become possible.

The deepest point in the ocean is the Mariana Trench, located in the Pacific Ocean near the Northern Mariana Islands. Its maximum depth has been estimated to be 10,971 metres (35,994 ft) (plus or minus 11 meters; see the Mariana Trench article for discussion of the various estimates of the maximum depth.) The British naval vessel, Challenger II surveyed the trench in 1951 and named the deepest part of the trench, the "Challenger Deep". In 1960, the Trieste successfully reached the bottom of the trench, manned by a crew of two men.

Much of the ocean bottom remains unexplored and unmapped. A global image of many underwater features larger than 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) was created in 1995 based on gravitational distortions of the nearby sea surface.[citation needed]

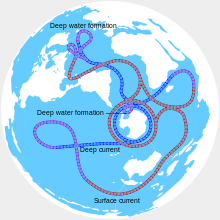

Climate

Ocean currents greatly affect the Earth's climate by transferring heat from the tropics to the polar regions. Transferring warm or cold air and precipitation to coastal regions, where winds may carry them inland. Surface heat and freshwater fluxes create global density gradients that drive the thermohaline circulation part of large-scale ocean circulation. It plays an important role in supplying heat to the polar regions, and thus in sea ice regulation. Changes in the thermohaline circulation are thought to have significant impacts on the Earth's radiation budget. In so far as the thermohaline circulation governs the rate at which deep waters reach the surface, it may also significantly influence atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations.

For a discussion of the possibilities of changes to the thermohaline circulation under global warming, see shutdown of thermohaline circulation.

It is often stated that the thermohaline circulation is the primary reason that the climate of Western Europe is so temperate. An alternate hypothesis claims that this is largely incorrect, and that Europe is warm mostly because it lies downwind of an ocean basin, and because atmospheric waves bring warm air north from the subtropics.[25][26]

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current encircles that continent, influencing the area's climate and connecting currents in several oceans.

One of the most dramatic forms of weather occurs over the oceans: tropical cyclones (also called "typhoons" and "hurricanes" depending upon where the system forms).

Biology

The ocean has a significant effect on the biosphere. Oceanic evaporation, as a phase of the water cycle, is the source of most rainfall, and ocean temperatures determine climate and wind patterns that affect life on land. Life within the ocean evolved 3 billion years prior to life on land. Both the depth and the distance from shore strongly influence the biodiversity of the plants and animals present in each region.[27]

Lifeforms native to the ocean include:

- Fish;

- Radiata, such as jellyfish (Cnidaria);

- Cetacea, such as whales, dolphins, and porpoises;

- Cephalopods, such as octopus and squid;

- Crustaceans, such as lobsters, clams, shrimp, and krill;

- Marine worms;

- Plankton; and

- Echinoderms, such as brittle stars, starfish, sea cucumbers, and sand dollars.

Gases

| Gas | Concentration of Seawater, by Mass (in parts per million), for whole Ocean | % Dissolved Gas, by Volume, in Seawater at Ocean Surface |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon dioxide (CO2) | 64 to 107 | 15% |

| Nitrogen (N2) | 10 to 18 | 48% |

| Oxygen (O2) | 0 to 13 | 36% |

| Temperature | O2 | CO2 | N2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0°C | 8.14 | 8,700 | 14.47 |

| 10°C | 6.42 | 8,030 | 11.59 |

| 20°C | 5.26 | 7,350 | 9.65 |

| 30°C | 4.41 | 6,600 | 8.26 |

Ocean Surface

| Characteristic | Oceanic Waters in Polar regions | Oceanic Waters in Temperate regions | Oceanic Waters in Tropical regions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precipitation vs. evaporation | P > E | P > E | E > P |

| Sea Surface Temperature in Winter | -2°C | 5 to 20°C | 20 to 25°C |

| Average Salinity | 28‰ to 32‰ | 35‰ | 35‰ to 37‰ |

| Annual Variation of Air Temperature | ≤ 40ªC | 10°C | < 5°C |

| Annual Variation of Water Temperature | < 5ªC | 10°C | < 5°C |

Mixing Time

Residence Time = The amount of the element in the ocean ÷ The rate at which that element is added to (or removed from) the ocean

The mean oceanic mixing time (residence time) is thought to be approximately 1,600 years. If a given element in the ocean stays in the ocean, on average, longer than the oceanic mixing time, then that element is assumed to be homogeneously spread throughout the ocean. As a result, since the major salts have a residence time that is longer than 1,600 years, the ratio of major salts is thought to be unchanging across the ocean. This constant ratio is often referred to as Forchhammer's principle or the principle of constant proportions.

| Constituent | Residence Time (in years) |

|---|---|

| Iron (Fe) | 200 |

| Aluminum (Al) | 600 |

| Manganese (Mn) | 1,300 |

| Water (H2O) | 4,100 |

| Silicon (Si) | 20,000 |

| Carbonate (CO32-) | 110,000 |

| Calcium (Ca2+) | 1,000,000 |

| Sulfate (SO42-) | 11,000,000 |

| Potassium (K+) | 12,000,000 |

| Magnesium (Mg2+) | 13,000,000 |

| Sodium (Na+) | 68,000,000 |

| Chloride (Cl-) | 100,000,000 |

Salinity

A zone of rapid salinity increase with depth is called ahalocline. The temperature of maximum density of seawater decreases as its salt content increases. Freezing temperature of water decreases with salinity, and boiling temperature of water increases with salinity. Typical seawater freezes at around -1.9°C at atmospheric pressure. If precipitation exceeds evaporation, as is the case in polar and temperate regions, salinity will be lower. If evaporation exceeds precipitation, as is the case in tropical regions, salinity will be higher. Thus, oceanic waters in polar regions have lower salinity content than oceanic waters in temperate and tropical regions. [40]

Salinity can be calculated using the chlorinity, which is a measure of the total mass of halogen ions (includes fluorine, chlorine, bromine, and iodine) in seawater. By international agreement, the following formula is used to determine salinity:

Salinity (in ‰) = 1.80655 x Chlorinity (in ‰)

The average chlorinity is about 19.2‰, and, thus, the average salinity is around 34.7‰ [40]

Economic value

The oceans are essential to transportation. This is because most of the world's goods move by ship between the world's seaports. Oceans are also the major supply source for the fishing industry. Some of the more major ones are shrimp, fish, crabs and lobster.[6]

Extraterrestrial oceans

- See also Extraterrestrial liquid water

While Earth is the only known planet with large stable bodies of liquid water on its surface and the only one in our Solar System, other celestial bodies are believed to possess large oceans.

Planets

The gas giants, Jupiter and Saturn, are thought to lack surfaces and instead have a stratum of liquid hydrogen, however their planetary geology is not well understood. The possibility of Uranus and Neptune possessing hot, highly compressed, supercritical water under their thick atmospheres has been hypothesised. While their composition is still not fully understood, a 2006 study by Wiktorowicz et al. ruled out the possibility of such a water "ocean" existing on Neptune,[41] though some studies have suggested that exotic oceans of liquid diamond are possible.[42]

The Mars ocean hypothesis suggests that nearly a third of the surface of Mars was once covered by water, though the water on Mars is no longer oceanic. The possibility continues to be studied along with reasons for their apparent disappearance. Astronomers believe that Venus had liquid water and perhaps oceans in its very early history. If they existed, all later vanished via resurfacing.

Natural satellites

A global layer of liquid water thick enough to decouple the crust from the mantle is believed to be present on Titan, Europa and, with less certainty, Callisto, Ganymede[43] and Triton.[44][45] A magma ocean is thought to be present on Io. Geysers have been found on Saturn's moon Enceladus, though their origins are not well understood. Other icy moons may also have internal oceans, or have once had internal oceans that have now frozen.[43]

Large bodies of liquid hydrocarbons are thought to be present on the surface of Titan, though they are not large enough to be described as oceans and are sometimes referred to as lakes or seas. The Cassini–Huygens space mission initially discovered only what appeared to be dry lakebeds and empty river channels, suggesting that Titan had lost what surface liquids it might have had. Cassini's more recent fly-by of Titan offers radar images that strongly suggest hydrocarbon lakes exist near the colder polar regions. Titan is thought to have a subterranean water ocean under the ice and hydrocarbon mix that forms its outer crust.

Dwarf planets and trans-Neptunian objects

Ceres appears to be differentiated into a rocky core and icy mantle and may harbour a liquid-water ocean under its surface.[46][47]

Not enough is known of the larger Trans-Neptunian objects to determine whether they are differentiated bodies capable of possessing oceans, although models of radioactive decay suggest that Pluto,[48] Eris, Sedna, and Orcus have oceans beneath solid icy crusts at the core-boundary approximately 100 to 180 km thick.[43]

Extrasolar

Some planets and natural satellites beyond the Solar System are likely to possess oceans, including possible water ocean planets similar to Earth in the habitable zone or "liquid-water belt". The detection of oceans, even through the spectroscopy method, however is likely to prove extremely difficult and inconclusive.

Theoretical models have been used to predict with high probability that GJ 1214 b, detected by transit, is composed of exotic form of ice VII, making up 75% of its mass.[49]

Other possible candidates are merely speculated based on their mass and position in the habitable zone include planet though little is actually known of their composition. Some scientists speculate Kepler-22b may be an "ocean-like" planet.[50] Models have been proposed for Gliese 581 d that could include surface oceans. Gliese 436 b is speculated to have an ocean of "hot ice".[51] Extrasolar moons orbiting planets, particularly gas giants within their parent star's habitable zone may theoretically possess surface oceans.

See also

- Blue carbon

- Effects of global warming on oceans

- European Atlas of the Seas

- International Maritime Organization

- Marine debris

- Marine pollution

- Ocean acidification

- Ocean current

- Oceanography

- Oceans (2009 film)

- Ogyges

- Pelagic zone

- Polar seas

- Sea

- Sea level and sea level rise

- Sea salt

- Sea state

- Seawater

- Seven Seas

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

- Water

- Wind waves

- World Ocean Atlas

- World Ocean Day

References

- ^ "Ὠκεανός". Perseus Digital Library. Retrieved May 17, 2012.

- ^ "WordNet Search — ocean". Princeton University. Retrieved February 21, 2012.

- ^ "ocean, n". Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- ^ "ocean". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved February 6, 2012.

- ^ "WordNet Search — sea". Princeton University. Retrieved February 21, 2012.

- ^ a b c "NOAA – National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration – Ocean". Noaa.gov. Retrieved 8-11-2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b Qadri, Syed (2003). "Volume of Earth's Oceans". The Physics Factbook. Retrieved 2007-06-07.

- ^ Charette, Matthew (2010). "The volume of Earth's ocean". Oceanography. 23 (2): 112–114. doi:10.5670/oceanog.2010.51. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Drogin, Bob (August 2, 2009). "Mapping an ocean of species". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 18, 2009.

- ^ "Titan Likely To Have Huge Underground Ocean | Mind Blowing Science". Mindblowingscience.com. Retrieved 8-11-2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b c d "Ocean-bearing Planets: Looking For Extraterrestrial Life In All The Right Places". Sciencedaily.com. Retrieved 8-11-2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) Cite error: The named reference "sciencedaily" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b "Distribution of land and water on the planet". UN Atlas of the Oceans

- ^ Spilhaus, Athelstan F. (July 1942). "Maps of the whole world ocean". 32 (3). American Geographical Society: 431–5.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c "Pacific Ocean – University of Delaware". Ceoe.udel.edu. Retrieved 8-11-2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Indian Ocean – Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia". Wikipedia.org. Retrieved 8-11-2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Indian Ocean – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 8-11-2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Limits of Oceans and Seas, 3rd edition" (PDF). International Hydrographic Organization. 1953. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ^ a b The World's Oceans and Seas. Encarta.

- ^ Drazen, Jeffrey C. "Deep-Sea Fishes". School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology, the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. Retrieved 2007-06-07.

- ^ Paula G. Coble "Marine Optical Biogeochemistry: The Chemistry of Ocean Color" Chemical Reviews, 2007, volume 107, pp 402–418. doi:10.1021/cr050350

- ^ Britt, Robert Roy (October 4, 2005). "Mystery Ocean Glow Confirmed in Satellite Photos".

- ^ Holladay, April (November 21, 2005). "A glowing sea, courtesy of algae". USA Today.

- ^ "Sea's eerie glow seen from space". New Scientist. October 5, 2005.

- ^ Casey, Amy (August 8, 2003). "The Incredible Glowing Algae". NASA Earth Observatory. NASA.

- ^ Seager, R. (2006). "The Source of Europe's Mild Climate". American Scientist.

- ^ Rhines and Hakkinen (2003). "Is the Oceanic Heat Transport in the North Atlantic Irrelevant to the Climate in Europe?" (PDF). ASOF Newsletter.

- ^ Biology: Concepts & Connections. Chapter 34: The Biosphere: An Introduction to Earth's Diverse Environment. (sec 34.7)

- ^ http://www.soest.hawaii.edu/oceanography/courses/OCN623/Spring2012/Non_CO2_gases.pdf

- ^ http://butane.chem.uiuc.edu/pshapley/GenChem1/L23/web-L23.pdf

- ^ http://www.seafriends.org.nz/oceano/seawater.htm

- ^ http://ocw.mit.edu/courses/earth-atmospheric-and-planetary-sciences/12-742-marine-chemistry-fall-2006/lecture-notes/lec_11_gas_exch.pdf

- ^ http://www.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/wg1/en/ch5s5-6.html

- ^ http://www.ecmwf.int/research/era/ERA-40/ERA-40_Atlas/docs/section_B/charts/B12_LL_YEA.html

- ^ Roger Graham Barry, Richard J. Chorley (2003). "Atmosphere, Weather, and Climate". [Routledge]. p. 68.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ http://eesc.columbia.edu/courses/ees/climate/lectures/o_strat.html

- ^ a b Rui Xin Huang (2010). "Ocean Circulation: Wind-Driven and Thermohaline Processes". [Cambridge University Press].

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ http://www.cgd.ucar.edu/cas/cdeser/Docs/deser.sstvariability.annrevmarsci10.pdf

- ^ http://oceanworld.tamu.edu/resources/ocng_textbook/chapter06/chapter06_03.htm

- ^ http://www.gly.uga.edu/railsback/3030/3030Tres.pdf

- ^ a b c Chester, Jickells, Roy, Tim (2012). Marine Geochemistry. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 225–230. ISBN 978-1-118-34907-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "Chester Marine Geochem" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Wiktorowicz, Sloane J.; Ingersoll, Andrew P. (2007). "Liquid water oceans in ice giants". Icarus. 186 (2): 436–447. arXiv:astro-ph/0609723. Bibcode:2007Icar..186..436W. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.09.003. ISSN 0019-1035.

- ^ Silvera, Isaac (2010). "Diamond: Molten under pressure". Nature Physics. 6 (1): 9–10. Bibcode:2010NatPh...6....9S. doi:10.1038/nphys1491. ISSN 1745-2473.

- ^ a b c Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2006.06.005, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi= 10.1016/j.icarus.2006.06.005instead. - ^ McKinnon, William B.; Kirk, Randolph L. (2007). "Triton". In Lucy Ann Adams McFadden, Lucy-Ann Adams, Paul Robert Weissman, Torrence V. Johnson (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Solar System (2nd ed.). Amsterdam; Boston: Academic Press. pp. 483–502. ISBN 978-0-12-088589-3.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Javier Ruiz (December 2003). "Heat flow and depth to a possible internal ocean on Triton". Icarus. 166 (2): 436–439. Bibcode:2003Icar..166..436R. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2003.09.009.

- ^ McCord, Thomas B. (2005). "Ceres: Evolution and current state". Journal of Geophysical Research. 110 (E5): E05009. Bibcode:2005JGRE..11005009M. doi:10.1029/2004JE002244.

- ^ Castillo-Rogez, J. C. (2007). "Ceres: evolution and present state" (PDF). Lunar and Planetary Science. XXXVIII: 2006–2007. Retrieved 2009-06-25.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Inside Story". pluto.jhuapl.edu — NASA New Horizons mission site. Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory. 2013. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- ^ David A. Aguilar (2009-12-16). "Astronomers Find Super-Earth Using Amateur, Off-the-Shelf Technology". Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. Retrieved January 23, 2010.

- ^ Abel Mendez Torres (2011-12-08). "Updates on Exoplanets during the First Kepler Science Conference". Planetary Habitability Laboratory at UPR Arecibo.

- ^ Fox, Maggie (May 16, 2007). "Hot "ice" may cover recently discovered planet". Reuters. Retrieved May 18, 2012.

Further reading

- Matthias Tomczak and J. Stuart Godfrey. 2003. Regional Oceanography: an Introduction. (see the site)

- Pope, F. 2009. From eternal darkness springs cast of angels and jellied jewels. in The Times. November 23. 2009 p. 16–17.

External links

- Oceans at Curlie

- Smithsonian Ocean Portal

- NOAA – National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration – Ocean

- Ocean :: Science Daily

- Ocean-bearing Planets: Looking For Extraterrestrial Life In All The Right Places

- Titan Likely To Have Huge Underground Ocean | Mind Blowing Science

- Origins of the oceans and continents". UN Atlas of the Oceans.