Catholic Church and Nazi Germany: Difference between revisions

read like OR and read badly after all the changes also - deleted the yad vesham which is assertions of Vatican opposition - better RS proof from academic sources of this opposition, not just assertions imo |

→Croatia: added Croatia -using Phayer only, so indeed maybe somewhat unbalanced - if made more exculpatory of Catholic stances could it be with academic RS - not all catholic websites though?? |

||

| Line 344: | Line 344: | ||

===Croatia=== |

===Croatia=== |

||

Nazi Germany dismembered Yugoslavia in the spring of 1941. Most of the former country fell to the new state of Croatia - a victory for [[Ante Pavelic]]'s [[Ustase]]. Unlike Hitler, Pavelic was pro-Catholic , but their ideologies overlapped sufficiently for easy co-operation. Pavelic wanted Vatican recognition for his fascist state and Croatian church leaders favoured an alliance with the Ustase because it seemed to hold out the promise of an anti-Communist, Catholic state. [[Aloysius Stepinac|Bishop Stepinac]], wanted the replacement of a religiously and ethnically diverse Yugoslav state ''the jail of the Croatian nation''. In May 1941 Stepinac arranged an audience with Pius XII for Pavelic. Pius and Stepinac both saw communism as the greaest mencace facing Christianity. <ref> Phayer, p.32</ref> The Vatican stopped short of formal recognition but Pius sent a [[Benedictine]] abbot, Giuseppe Ramiro Marcone, as his apostolic visitor. This suited Pavelic well enough and Stepinac felt the Vatican had ''de facto'' recognised the new state. |

|||

{{expand section|date=May 2013}} |

|||

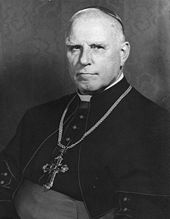

[[File:NDH - salute.jpg|thumb|[[Aloysius Stepinac]] (far right), initially a supporter of the [[Ustaše]] government, he distanced himself-but the Vatican preferred diplomatic pressure to public denunciations of the immorality of genocide. And Stepinac,like Pius XII wanted to see a Catholic state succeed in Croatia.<ref>Phayer pp35-39</ref>]] |

|||

In April and May 1941 thousands of Serbs were murdered and Nazi copycat laws eliminated Jewish citizenship and compelled the wearing of the Star of David. The German army pulled out of Croatia in June 1941. Stepinac was a supporter of the Ustashi initially, but as the terror continued he began, from May 41, to begin a distancing process; in July he wrote to Pavelic objecting to the condition of deportation of Jews and Serbs and then, realizing that conversion could save Serbs he instructed clergy to baptise people upon demand without the usual waiting and instruction. Summer and autumn of 1941 Ustasha murders increased - but Stepinac was not yet prepared to break with the Ustase regime totally. Some bishops and priests collaborated openly with Pavelic and even served in Pavelic's body guard, Ivan Guberina, the leader of [[Catholic Action]],among them. [[Catholic clergy involvement with the Ustaše|Notorious examples of collaboration]] included Bishop [[Ivan Šarić]] and the [[Franciscan]] [[Miroslav Filipovic-Majstorovic]], 'the devil of the [[Jasenovac]]'. |

|||

[[Giovanni Battista Montini]] , later [[Paul VI]], kept Pius informed of matters in Croatia - and [[Domenico Tardini]] interviewed Pavelic's representative to Pius; he let the Croat know the Vatican would be indulgent - "Croatia is a young state - Youngsters often err because of their age. It is therefore not surprising that Croatia has also erred." <ref> Michael Phayer, p.37</ref> |

|||

In 1943 after the German military became active once again in Croatia 6-7000 Jews were deported to [[Auschwitz]], and others murdered in [[gas vans]] in Croatia. Rather than jeopardize the Ustase government of Croatia by diplomatic wrangling the Vatican chose to help Jews privately - but the chaos of the country meant this was little. Historian John Morley has called the Vatican record particularly shameful in Croatia because it was a state that proudly proclaimed its Catholic tradition and whose leaders depicted themselves as loyal to the Church and to the Pope.<ref>Phayer, p.39</ref> Diplomatic pressure was preferred to public challenges on the immorality of genocide and Pavelic's diplomatic emissaries to the Holy See were merely scolded by Tardini and Montini. At the war's end leaders of the Ustasha including its clericals supporters such as Saric fled, taking gold looted from massacred Jews and Serbs with them. |

|||

===Hungary=== |

===Hungary=== |

||

Revision as of 12:30, 14 May 2013

Two Popes served through the rise and fall of Nazi Germany - Pius XI (1922–39) and Pius XII (1939–58). In January 1933, the nominally functioning Weimar Republic and its aging President Paul von Hindenburg appointed Adolf Hitler as Chancellor and Franz von Papen Vice-Chancellor of the Reichstag. In July 1933, the Vatican reached a Concordat (treaty) with Germany. This treaty remains in force, but was routinely violated by Hitler, particularly, after the Nazis achieved a totalitarian dictatorship following the August 1934 death of Paul von Hindenburg. Hitler and Nazi ideology were, in many respects, hostile to Catholicism. Nazi philosopher Alfred Rosenberg identified Catholicism as an enemy of Nazism. He and Hitler advocated "Positive Christianity" derived from the, "Deutsche Christens" (an apostate sect), which attempted to align Protestants with an Aryan theology that denounced the Jewishness of the Old Testament and invented an "Aryan Jesus" as a transition to a new Nazi faith. Vatican objections to Nazi ideology and "Positive Christianity" were outlined in Pius XI's 1937 Mit brennender Sorge encyclical.

Pius XII, a cautious diplomat, was pope for the duration of World War Two, and pursued a policy of Vatican neutrality, while employing diplomacy to aid the victims of the conflict.[2] His 1939 Summi Pontificatus encyclical responded to the Nazi/Soviet invasion of Poland. It expressed dismay at the outbreak of war, reiterated Catholic teaching against racism, called for compassion for victims of the war and expressed hope for the resurrection of Poland. Pius instructed local hierarchies to assess and respond to their local situations under the Nazis, and local Catholic responses to the Nazis varied accordingly. Although his personal interventions are credited with saving many Jews from the Holocaust, his overall caution became a focus of scholarly and theological debate and some controversy.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Catholic leaders made a number of forthright criticisms of Nazism. Hitler courted Catholic support during his negotiations for power, and was often cautious in his approach to the German Churches, but following the Nazi takeover, the overall Nazi policy of Gleichschaltung sought to establish control and coordination of all aspects of German society and the Catholic Church in Germany faced constant harassment and persecutions. The Concordat restricted the Church to ecclesiastical affairs, the Catholic Centre Party - solely a political entity - was dissolved, while critics of the government faced harsh punishment. The German Catholic Church was divided on how to respond to Hitler, with bishops protesting policies like Nazi eugenics and Nazi euthanasia, but not speaking against other policies. Joachim Fest, wrote that, while the Church was initially quite hostile, and bishops denounced Nazi "false doctrines", opposition weakened after the Concordat: "Cardinal Bertram developed an ineffectual protest system [-] Resistance remained largely a matter of individual conscience. In general they [both churches i.e. Catholic and Protestant] attempted merely to assert their own rights and only rarely issued pastoral letters or declarations indicating any fundamental objection to Nazi ideology."[3] The Church was brutally suppressed in Poland under Nazi occupation, and thousands of clergy and religious from across the Nazi Empire died in concentration camps - but nationalist Nazi puppet regimes in Slovakia and Croatia sought to associate themselves with the Church. The actions of the church in relation to Nazism were complex and remain a matter of scholarly debate and investigation.

Background

Although the majority of Germans proclaimed to be Christian either Protestant [67%] or Catholic [33%] in 1933,[4] Adolf Hitler and senior lieutenants including Martin Bormann and Alfred Rosenberg were hostile to Christianity, and ultimately intended to eradicate the churches under a Nazi future.[5][6]

As the Holy See had done during the pontificate of Benedict XV (1914 - 1922) during World War One, the Vatican under, Pius XII (Feb. 1939 - Sept. 1958), pursued a policy of diplomatic neutrality through World War Two - Pius XII, like Benedict XV, described the position as "impartiality", rather than "neutrality.[7] The Catholic Church sought to preserve its position in Germany by signing a Concordat in 1933. Despite various Nazi violations of the Concordat, the Church was among the very few institutions in Germany which retained a measure of independence from the state.[8] The Vatican issued two encyclicals opposing the policies of Mussolini and Hitler: Non Abbiamo Bisogno in 1931 and Mit Brennender Sorge in 1937, respectively. Mit Brennender Sorge was written partially in response to the Nuremburg Laws and included criticisms of Nazism and racism. The Pope advocated for peace and spoke against racism, selfish nationalism, atrocities in Poland, the bombardment of civilians and other issues.

Pius XII's relations with the Axis and Allied forces may have been impartial, and his policies tinged with uncompromising anti-communism, but early in the war he shared intelligence with the Allies about the German Resistance and planned invasion of the Low Countries and lobbied Mussolini to stay neutral.[9] With Poland overrun, but France and the Low Countries yet to be attacked, Pius continued to hope for a negotiated peace to prevent the spread of the conflict. The similarly minded US President Franklin D. Roosevelt re-established American diplomatic relations with the Vatican after a seventy year hiatus by dispatching Myron C. Taylor as his personal representative.[10] Pius warmly welcomed Roosevelt's envoy.[11] Taylor urged Pius XII to explicitly condemn Nazi atrocities. Instead, Pius XII spoke against the "evils of modern warfare", but did not go further.[12] This may have been so for fear of Nazi retaliation experienced previously with the issuance of the encyclical Mit Brennender Sorge in 1937.[13] Pius XII allowed national hierarchies to assess and respond to their local situations and utilized Vatican Radio to promote aid to thousands of war refugees, and saved further thousands of lives by instructing the church to provide discreet aid to Jews.[12] To confidantes, Hitler scorned Pius XII as a blackmailer on his back,[14] whom he believed constricted his ally Mussolini and leaked confidential German correspondence to the world.[15] For opposition from the Church he vowed "retribution to the last farthing" after the conclusion of the war.[16]

Around one third of Germans were Catholic when Adolf Hitler's Nazi Party began to take control of Germany in 1933. Through this period, the Catholic Center Party had competed against the Nazis in German elections until it self-dissolved to comply with the Reichskoncordat of July 1933, and Catholic leaders had been among the major opponents of Nazism. By 1930, the Nazis and the German Communists controlled over 50% of the German Parliament. Both (the Nazi and Communist Parties) opposed parliamentary democracy leading Germany into an extended constitutional crisis. On February 27, 1933, just prior to the March 1933 federal elections, the Reichstag building was destroyed by arson. The crime was blamed on the Communist - though this remains unclear. Some suggest this was staged by the Nazi Party. Nevertheless, Hitler convinced the President, Hindenburg, to support legislation called the Reichstag Fire Decree that greatly restricted civil liberties, such as, freedom of assembly. This led to the exclusion of the Communist Party from the Reichstag at the behest of Hitler just before the elections were to take place. Following the German federal election, March 1933 no single party secured a majority. Through a mixture of negotiation, and intimidation via Hitler's paramilitary (private army) known as the Sturmabteilung threatening civil war, the Nazi Party convinced the Catholic Centre Party, led by Ludwig Kaas, and all other parties in the Reichstag, save the Social Democrats, to vote with the Nazis for the Enabling Act on 24 March 1933. The Act granted Hitler "temporary" limited "dictatorial' powers. By the end of July 1933, Hitler had maneuvered to ban all other political parties in Germany, save the Centre Party's self-dissolution, and commenced a wide program of persecutions.

The Reichskonkordat was signed on July 20, 1933, and is still in force. Under the Concordat, the church was promised autonomy of ecclesiastical institutions and their religious activities but had to cease political activism (political Catholicism). Article 16 required the Bishops of Germany to take an oath of loyalty to the German Reich i.e., the constitutional government of Germany.[17][18] Hitler welcomed the agreement, but it was the first of many international treaties he would violate, and proceeded to repress the activities of the Church along with all other non-Nazi institutions.

Though both Catholics and Protestants were subject to oppression under the Nazis, and notable figures notwithstanding, it has been argued (by some) that they largely conformed to the regime's demands Joachim Fest, a noted biographer of Adolf Hitler, wrote that; "At first the Church was quite hostile and its bishops energetically denounced the "false doctrines" of the Nazis. Its opposition weakened considerably in the following years [after the Concordat] [-] Cardinal Bertram developed an ineffectual protest system [-] Resistance remained largely a matter of individual conscience. In general they [both churches] attempted merely to assert their own rights and only rarely issued pastoral letters or declarations indicating any fundamental objection to Nazi ideology."[3]

Hitler, had contempt for the central teachings of Catholicism, but was impressed by its organisational power and position.[19] The official Nazi philosopher Alfred Rosenberg strongly opposed Christianity. With German conservatives - notably the army officer corps - holding the churches in high regard however, in office, Hitler restrained the full force of his anti-clericalism out of political considerations.[19] The Nazis nevertheless arrested thousands of members of the German Catholic Centre Party, as well as Catholic clergymen and closed Catholic schools and institutions. The German bishops were divided on how to respond to Hitler: Cardinal Bertram, favoured a policy of concessions, whilst Bishop Preysing of Berlin called for more concerted opposition, including public protests.[20] The Bishop of Munster led condemnations of euthanasia in Nazi Germany.

Though Catholics fought on both sides through the war, the Catholic Church and many of its members protested Nazi ideology and policy in various ways. Among the many thousands of Catholic religious sent to the Nazi death camps were Saints Edith Stein and Maximillian Kolbe, who died at Auchwitz. The Polish church suffered mass persecution with around 3000 clergy killed.[21] Around 0.5% of German clerics are believed to have been so-called "brown priests" (Nazi collaborators) - around 138 of 42,000.[22] Some 447 German priests were sent to the Priest Barracks of Dachau Concentration Camp.[23] In 2000 the Catholic Church acknowledged its use of some forced labour mainly in hospitals, homes and monastery gardens in the Nazi era and Cardinal Karl Lehmann stated, "It should not be concealed that the Catholic Church was blind for too long to the fate and suffering of men, women and children from the whole of Europe who were carted off to Germany as forced laborers".[24]

Political Catholicism

In the 1930s, the Catholic Church and the Catholic Centre Party, were major social and political forces in Protestant dominated Germany. The Centre Party was created in response to Otto von Bismark's Kulturkampf policies (1871–78) to reduce the social and political influence of the Catholic Church in Germany. The Centre Party was challenged and weakened by the subsequent rise of socialism, communism and National Socialism. The Bavarian region, the Rhineland and Westphalia as well as parts in south-west Germany were predominantly Catholic, and the church had previously enjoyed a degree of privilege there. North Germany was heavily Protestant, and Catholics had suffered some discrimination. The Kulturkampf failed in its attempt to eliminate Catholic institutions in Germany, or at least their strong connections outside of Germany. The revolution of 1918 and the Weimar constitution of 1919 had thoroughly reformed the former relationship between state and churches.

Through the period of the Weimar Republic, (1919-33/34) the Catholic aligned Catholic Centre Party and the Social Democrat Party had maintained the centre ground against the rise of extremist parties of the left and right.[25] With the collapse of Germany's post-World War One Economic recovery, and the stain of defeat laying heavily on the German psyche, political and economic extremism ultimately won out against the centre, through a combination of shrewd politics and terror tactics. By law, the German churches (Protestant and Catholic) received tax supported subsidies based on church census data, therefore, were dependent on the state support causing them to be vulnerable to Government influence and the political atmosphere of Germany.[25]

With this background, Catholic officials pursued a concordat strongly guaranteeing the church's freedoms. In 1929, Eugenio Pacelli's brother, Francesco, had successfully negotiated a concordat with Mussolini as part of an agreement known as the Lateran Treaty. A precondition of the these Italian negotiations involved the dissolution of the parliamentary Catholic Italian People's Party. The Holy See represented in Germany by Nuncio Eugenio Pacelli, the future Pope Pius XII, made unsuccessful attempts to obtain an agreement with the federal government of Germany for such a treaty. Between 1930 and 1933 he attempted to initiate negotiations with representatives of successive German governments with limited success. He secured several state level concordats, however, a federal treaty proved elusive .[26] Catholic politicians from the Centre Party repeatedly pushed for a concordat with the new German Republic. In February 1930 Eugenio Pacelli became the Vatican's Secretary of State, and thus responsible for the Church's foreign policy, and in this position continued to work towards this 'great goal' of securing a treaty with the federal government.[26][27]

- Catholic opposition to Communism

The Catholic Church held grave fears as to the consequences of Communist conquest or revolution in Europe. German Christians were alarmed by the aggressive spread of militant atheism in Russia.[28] The ambivalent views held by 19th century German sociologist Karl Marx on religion had pitted Communist movements against religious organisations like the Catholic Church. In Bavaria in 1919, Communists briefly seized power. Papal Nuncio Eugenio Pacelli (later Pope Pius XII) was harassed, threatened at gunpoint and his residence sprayed with machine gun fire by revolutionaries.[29]

Militant Marxist‒Leninist atheism took hold in Russia following the 1917 Communist Revolution, which was followed by a systematic effort to eradicate Christianity: with lootings, lynchings, executions, the banning of church rites and orchestrated mockery of priests, popes and rabbis.[30] Seminaries were closed and teaching the faith to the young was criminalized. In 1922, the Bolsheviks arrested the Patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church.[31] The Soviet leaders Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin energetically pursued the persecution of the Russian Orthodox Church through the 1920s and 1930s. Lenin wrote:[32]

Every religious idea, every idea of God... is unutterable vileness...of the most dangerous kind, 'contagion' of the most abominable kind. Millions of sins, filthy deeds, acts of violence and physical contagions... are less dangerous than the subtle, spiritual idea of God decked out in the smartest 'ideological' costumes.

Hitler was able to win some support from some German Christians in the belief that he would be a bulwark against Communism.[33]

Rise of Nazism

With Germany deep in financial crisis, the National Socialist German Workers Party (Nazis) and German Communist parties made great gains at the 1930 German Election. Both sides were pledged to eliminate German democracy, but between them had obtained over 50% of seats in the Reichstag, requiring the Social Democrats and Catholic Centre Party to consider negotiations with non-democrats.[34] The Centre Party had been an important player in Weimar democracy, aligned with both the Social Democrats and the leftist German Democratic Party against right wing parties like the Nazis.[35]

At the July 1932 German Elections, the Nazis became the largest party in the Reichstag, though their vote declined at the November 1932 Election. The conservative President Paul von Hindenburg appointed the Catholic monarchist Franz von Papen Chancellor in June 1932, and sacked him in December. Papen returned to office in Coalition with the Nazis in January 1933 - falsely believing he could tame Hitler by stacking the Cabinet with fellow non-Nazi nationalists.[36] Initially, Papen did speak out against some Nazi excesses, and only narrowly escaped death in the night of the long knives, whereafter he ceased to criticize the regime.

Hitler was appointed chancellor by the President of the Weimar Republic, Paul von Hindenburg, on January 30, 1933. Still requiring the vote of the Centre Party and conservatives in the Reichstag to obtain the powers he desired, in an address to the Reichstag on March 23 he said that Positive Christianity belief was the "unshakeable foundation of the moral and ethical life of our people". On March 24, 1933, with Nazi paramilitary (private army) encircling the building, and threatening civil war if his demands weren't met, Hitler was granted (quasi) dictatorial powers "temporarily" by the Reichstag, through the Enabling Act.[37] He would not achieve full dictatorial power until the death of the President, Paul von Hindenburg, on August 2, 1934 Nazi Germany.

Hitler promised not to threaten institutions like the churches (Catholic and Protestant) if granted the powers,[37] He promised to honour the previously negotiated concordats of the Holy See with individual German states, to maintain government support for church-related schools, uphold religious education in the public schools and promised he would secure a good working relationship with the papacy.[citation needed] After Hitler's speech he was given temporary and quasi dictatorial powers through an Enabling Act. It was passed by all parties in the Reichstag except the Social Democrats and Communists (whose deputies had already been arrested). The Enabling Act of 1933 did not infringe the on the powers of the President, Paul von Hindenburg, who remained the Commander and Chief of the military and the sole principle of foreign affairs and treaties after the Enabling Act became law and until his death in August 1934.

Hitler had obtained the votes of the Centre Party, led by Prelate Ludwig Kaas, by intimidation and offering oral guarantees of the party's continued existence and the autonomy of the Church and her educational institutions. Chairman Kaas advocated supporting the bill in parliament in return for government guarantees. These mainly included respecting the Church's liberty, its involvement in the fields of culture, schools and education, the concordats previously signed by German states, and the continued existence of the Centre Party itself. Kaas was aware of the doubtful nature of such guarantees, but when the Centre Party assembled on 23 March to decide on their vote, Kaas advised his fellow party members to support the bill, given the "precarious state of the party". He described his reasons as follows: "On the one hand we must preserve our soul, but on the other hand a rejection of the Enabling Act would result in unpleasant consequences for faction and party. What is left is only to guard us against the worst. Were a two-thirds majority not obtained, the government's plans would be carried through by other means. The President has acquiesced in the Enabling Act. From the DNVP no attempt of relieving the situation is to be expected."

A number of Centre Party parliamentarians opposed the chairman's course, among these former Chancellors Heinrich Brüning, Joseph Wirth and former minister Adam Stegerwald. Brüning called the Act the "most monstrous resolution ever demanded of a parliament", and was sceptical about Kaas' efforts: "The party has difficult years ahead, no matter how it would decide. Sureties for the government fulfilling its promises have not been given. Without a doubt, the future of the Centre Party is in danger and once it is destroyed it cannot be revived again." The Catholic Centre Party party was disbanded and thousands of its members rounded up.[39] Several of the leaders of the Party were murdered in the 1934 Night of the Long Knives.[35] The bishops' decision opened the way for a Reichskonkordat between the Holy See and Hitler's government.[40] According to the historian Alan Bullock, in Weimar Germany, the Catholic Centre Party had been "notoriously a Party whose first concern was to make accommodation with any government in power in order to secure the protection of its particular interests", and, having obtained promises of non-interference in religion, joined conservatives in the Reichstag vote giving Hitler dictatorial powers.[41]

Catholic opposition to rise of Nazi Party

During the 1920s and 1930s, Catholic leaders made a number of forthright attacks on Nazi ideology and the main Christian opposition to Nazism in Germany had come from the Catholic Church.[25] Before Hitler came to power, German bishops warned Catholics against Nazi racism and some dioceses banned membership of the Nazi Party.[42] The Catholic press condemned Nazism.[43] John Cornwell wrote of the early Nazi period that:

Into the early 1930s the German Centre Party, the German Catholic bishops, and the Catholic media had been mainly solid in their rejection of National Socialism. They denied Nazis the sacraments and church burials, and Catholic journalists excoriated National Socialism daily in Germany's 400 Catholic newspapers. The hierarchy instructed priests to combat National Socialism at a local level whenever it attacked Christianity.[44]

Cardinal Michael von Faulhaber was appalled by the totalitarianism, neopaganism, and racism of the Nazi movement and, as Archbishop of Munich and Freising, contributed to the failure of the Nazi Munich Putsch of 1923.[45] At a basic philosophical level, Catholic theology clashed in various respects with key tenets of Nazism.[46] The Nazi philosopher Alfred Rosenberg's Myth of the Twentieth Century outlines some of these clashes from the Nazi point of view and Pope Pius XI's Mit brennender Sorge encyclical (1937) and the unpublished encyclical, Humani generis unitas ("The Unity of the Human Race"), addressed various clashes from the Catholic point of view.[47]

Catholicism's internationalism, was at odds with Nazism's uber-nationalism. The position of reverence given by the Church to the Jewish patriarchs and Old Testament contradicted Nazism's racial ideology which classed Jews as sub-human. The Nazi glorification of war and the "survival of the fittest" clashed sharply with the Beatitudes of Jesus that "blessed are the peacemakers". While Catholicism preached of the primacy of conscience, Hitler denounced conscience as a contemptible "Jewish invention". Thus Hitler intended ultimately to eradicate the Christian Churches.[48] Throughout the Nazi period Catholic institutions continued to preach the Beatitudes - in cultural opposition to Nazism.

At the beginning of 1931, the Cologne Bishops Conference condemned National Socialism, and were followed by the bishops of Paderborn and Freiburg. With ongoing hostility to the Nazis from the Catholic press and the Catholic Center Party, few German Catholics voted Nazi in the elections preceding the Nazi takeover in 1933.[49] Nevertheless, in Catholicism, as in other German churches, there were clergy and lay people who openly supported the Nazi regime.[35]

Nazi opposition to Catholicism

Unlike some Fascist movements of the era, Nazi ideology was hostile to Christianity and clashed with Christian beliefs in many respects.[51] Nazism saw Christian ideals of meekness and conscience as obstacles to the violent instincts required to defeat other races.[51] Aggressive anti-Church radicals like Joseph Goebbels and Martin Bormann saw the conflict with the Churches as a priority concern, and anti-church and anti-clerical sentiments were strong among grassroots party activists.[52] The attitude of the Nazi party membership to the Catholic Church ranged from tolerance to near total renunciation.[53][54] The Nazi party had decidedly pagan elements.[55] According to biographer Alan Bullock, once the war was over, Hitler wanted to root out and destroy the influence of the churches:.[5]

In Hitler's eyes, Christianity was a religion fit only for slaves; he detested its ethics in particular. Its teaching, he declared, was a rebellion against the natural law of selection by struggle and the survival of the fittest.

— Extract from Hitler: a Study in Tyranny, by Alan Bullock

Bullock wrote that that Hitler "believed neither in God nor in conscience".[56] Raised Catholic, he retained some regard for the organisational power of Catholicism, but had utter contempt for its central teachings, which he said, if taken to their conclusion, "would mean the systematic cultivation of the human failure".[57] Hitler ultimately believed "one is either a Christian or a German" - to be both was impossible.[58] However, important German conservative elements, such as the officer corps, opposed Nazi persecution of the churches and, in office, Hitler restrained his anticlerical instincts out of political considerations.[57][59]

Joseph Goebbels, the Minister for Propaganda, was among the most aggressive anti-Church Nazi radicals. Goebbels led the Nazi persecution of the German clergy and, as the war progressed, on the "Church Question", he wrote "after the war it has to be generally solved... There is, namely, an insoluble opposition between the Christian and a heroic-German world view".[52]

Hitler's chosen deputy and private secretary, Martin Bormann, was a rigid guardian of National Socialist orthodoxy and saw Christianity and Nazism as "incompatible" (mainly because of its Jewish origins),[51][60] as did the official Nazi philosopher, Alfred Rosenberg.[49] In his "Myth of the Twentieth Century" (1930), Rosenberg wrote that the main enemies of the Germans were the "Russian Tartars" and "Semites" - with "Semites" including Christians, especially the Catholic Church.[61] Rosenberg and Bormann actively collaborated in the Nazi program to eliminate Church influence - a program which included the abolition of religious services in schools; the confiscation of religious property; ciculating anti-religious material to soldiers; and the closing of theological faculties.[62]

John Cornwell wrote that Hitler was continually preoccupied by "the fact that German Catholics, politically united by the Centre Party, had defeated Bismarck's Kulturkampf -- the "culture struggle" against the Catholic Church in the 1870s". Hitler was convinced that his movement could succeed only if political Catholicism and its democratic networks were eliminated.[44] Hitler and Mussolini were anticlerical, but both were wary of beginning their Kulturkampfs prematurely - preferring to postpone such a clash, while dealing with other enemies.[63] One position[vague] is that the Church and fascism could never have a lasting connection because both are a "holistic Weltanschauung" claiming the whole of the person.[53]

The 1920 Nazi Party Platform had promised to support freedom of religions with the caveat: "insofar as they do not jeopardize the state's existence or conflict with the moral sentiments of the Germanic race". It further proposed a definition of a "positive Christianity" which could combat the "Jewish-materialistic spirit".[35] But German Catholics met the Nazi takeover with apprehension, as leading clergymen had been warning against Nazism.[64] A threatening, though initially mainly sporadic persecution of the Catholic Church in Germany commenced.[65] However, amidst a backlash of the failures of the Weimar Republic, widespread anti-Semitism, strong anti-Communist sentiment, surging nationalism, and ongoing resentment at the terms of the Treaty of Versailles and Germany's loss of World War One - many German Christians welcomed or accepted the arrival of the Nazis in power in 1933.

- Nazi ideologist Alfred Rosenberg

Alfred Rosenberg was the original draftsman and spokesman of the Nazi Party program and official ideologist of the Nazi Party. He was a rabid anti-Semite and anti-Catholic who described Catholicism as a promoter of "prodigious, conscious and unconscious falsifications".[35][66] In his "Myth of the Twentieth Century" (1930), Rosenberg wrote that Germans were entitled to dominate Europe and that their enemies were Russian Tartars and Semites. Semites included Jews, Latins, and Christianity - especially the Catholic Church.[67] Rosenberg proposed to replace traditional Christianity with the neo-pagan "myth of the blood"[62]

We now realize that the central supreme values of the Roman and the Protestant Churches, being a negative Christianity, do not respond to our soul, that they hinder the organic powers of the peoples determined by their Nordic race, that they must give way to them, that they will have to be remodeled to conform to a Germanic Christendom. Therein lies the meaning of the present religious search.

— The Myth of the 20th Century, Alfred Rosenberg, 1930.

On January 24, 1934 Hitler appointed Alfred Rosenberg as the state's official philosopher.[citation needed] Church officials were perturbed - the indication was that Hitler was officially espousing the anti-Jewish, anti-Christian, and neopagan ideas presented in Rosenberg's Myth of the Twentieth Century.

Pius XI and Cardinal Pacelli directed the Holy Office to place Rosenberg's Myth of the Twentieth Century on the Index of Forbidden books on February 7, 1934. Cologne's Cardinal Schulte met with Hitler, and protested at Rosenberg's role in the government. Ignored by Hitler, Schulte decided that the church needed to respond and appointed the Reverend Josef Teusch to direct a defence against the Nazi anti-Christian propaganda. Teusch eventually produced 20 booklets against Nazism - Catechism Truths alone sold seven milion copies.[68] Later in 1934 Studien zum Mythus des XX, a pamphlet of essays attacking Rosenberg's Myth of the Twentieth Century, was released, in Bishop Clemens von Galen's name. "Studien was a defence of the church. A concern for the preservation of Catholicism had apparently eclipsed a commitment to the protection of human rights in general."[69]

Nazis take power

In January 1933, Hitler and the Nazi Party began the Machtergreifung seizure of power in Germany. Hitler was appointed chancellor of a coalition government of the NSDAP-DNVP Party by the President of the Weimar Republic Paul von Hindenburg. The Nazis began to suspend civil liberties and eliminate political opposition. Within a few months, a one-party dictatorship had been installed in Germany. German Catholics met the Nazi takeover with apprehension, as leading clergymen had been warning against Nazism for years.[64] A threatening, though initially mainly sporadic persecution of the Catholic Church in Germany commenced.[65]

Hitler moved quickly to eliminate Political Catholicism. In February 1933, Hermann Goering banned Catholic newspapers in Cologne, on the basis that political Catholicism would not be tolerated (after protests, the ban was lifted) and the SA began breaking up meetings of the Centre Party and Christian trade unions.[70] By June, thousands of Centre Party members would be incarcerated in concentration camps. In this threatening atmosphere, Hitler publicly called for a reorganization of Church and State relations of both Catholic and Protestant Churches. Two thousand functionaries of the Bavarian People's Party were rounded up by police in late June 1933, and it, along with the national Catholic Centre Party, ceased to exist in early July.[71]

Reichskonkordat

Kershaw wrote that the Vatican was anxious to reach agreement with the new government, despite "continuing molestation of Catholic clergy, and other outrages committed by Nazi radicals against the Church and its organisations".[72] The non-Nazi Vice Chancellor, Franz von Papen was chosen by the new government to negotiate for a Reich Concordat with the Vatican.[71]

The bishops announced on April 6 that negotiations toward a concordat between the Holy See and Germany would soon begin in Rome.[73] On April 10, Francis Stratmann O.P., who was a chaplain to students in Berlin wrote to Cardinal Faulhaber, "The souls of the well-intentioned are deflated by the National Socialist seizure of power - the bishops' authority is weakened among countless Catholics and non-Catholics because of their quasi-approbation of the National Socialist movement." Some Catholic critics of the Nazis soon chose to emigrate - among them Waldemar Gurian, Dietrich von Hildebrand, and Hans A. Reinhold.[74] Hitler began enacting laws restricting movement of funds (making it impossible for German Catholics to send money to missionaries, for instance), restricting religious institutions and education, and mandating attendance at Hitler Youth functions (held on Sunday mornings to interfere with Church attendance).[citation needed]

On April 8 Vice Chancellor Papen, went to Rome. Von Papen, a Catholic nobleman, had formerly been a member of the right-wing of the Catholic Centre Party.[75] On behalf of Cardinal Pacelli, Ludwig Kaas, the out-going chairman of the Centre Party, negotiated the draft of the terms with Papen. Throughout the years of the Weimar Republic, Protestants, Socialists, and the National Socialists had been a staunch opponents of such an agreement. The Centre Party's chairman Kaas had arrived in Rome shortly before Papen; because of his expertise in Church-State relations, he was authorized by Cardinal Pacelli to negotiate terms with Papen, but pressure by the German government forced him to withdraw from visibly participating in the negotiations. He met the representative of the German Bishops’ Conference, Bishop Wilhelm Berning of Osnabrück, -who held favourable views of Hitler- [76] on April 26. At the meeting, Hitler declared to Bishop Berning:

I have been attacked because of my handling of the Jewish question. The Catholic Church considered the Jews pestilent for fifteen hundred years, put them in ghettos, etc., because it recognized the Jews for what they were. In the epoch of liberalism the danger was no longer recognized. I am moving back toward the time in which a fifteen-hundred-year-long tradition was implemented. I do not set race over religion, but I recognize the representatives of this race as pestilent for the state and for the Church, and perhaps I am thereby doing Christianity a great service by pushing them out of schools and public functions.

The notes of the meeting do not record any response by Bishop Berning. In the opinion of the Opus Dei priest of Jewish descent Martin Rhonheimer; "This is hardly surprising: for a Catholic Bishop in 1933 there was really nothing terribly objectionable in this historically correct reminder. And on this occasion, as always, Hitler was concealing his true intentions."[77] The issue of the concordat prolonged Kaas' stay in Rome, leaving the party without a chairman, and on 5 May Kaas finally resigned from his post. The party now elected Heinrich Brüning as chairman. At that time, the Centre party was subject to increasing pressure in the wake of the process of Gleichschaltung and after all the other parties had dissolved, or were banned by the NSDAP, and the Centre Party dissolved itself on 6 July.

The bishops saw a draft of the Reich Concordat on May 30, 1933 when they assembled for a joint meeting of the Fulda bishops conference, (led by Breslau's Cardinal Bertram), and the Bavarian bishops' conference, (whose president was Munich's Michael von Faulhaber). Bishop Wilhelm Berning of Osnabruck, and Archbishop Conrad Grober of Freiburg presented the document to the bishops.[78] The strongest critics of the concordat were Cologne's Cardinal Karl Schulte and Eichstatt's Bishop Konrad von Preysing who pointed out that since the Enabling Act had established a quasi dictatorship, the church lacked legal recourse if Hitler decided to disregard the concordat.[78] Notwithsatnding, the bishops approved the draft and delegated Grober, a friend of Cardinal Pacelli and Monsignor Kaas, to present the episcopacy's concerns to Pacelli and Kaas. On June 3, the bishops issued a statement, drafted by Grober, that announced their support for the concordat.

Though the Vatican tried to hold back the exclusion of Catholic clergy and organizations from politics during the negotiations,[citation needed] which had been one of Hitler's foremost reasons for seeking the Concordat,[79] Cardinal Pacelli had acquiesced in the party's dissolution but was nonetheless dismayed that it occurred before the negotiations had been concluded. The day after, the government issued a law banning the founding of new political parties, thus turning the NSDAP into the party of the German state. On 14 July 1933 the Weimar government accepted the Concordat, which was signed a week later by President Hindenburg and the Vice Chancellor Papen. Shortly before signing the Reichskonkordat on 20 July, Germany signed similar agreements with the major Protestant churches in Germany. The concordat was finally signed, by Pacelli for the Vatican and von Papen for Germany, on 20 July. The Reichskonkordat was ratified on September 10, 1933. Article 16 required bishops to make an oath of loyalty to the state. Article 31 acknowledged that while the church would continue to sponsor charitable organisations, it would not support political organisations or political causes. Article 31 was supposed to be supplemented by a list of protected catholic agencies but this list was never agreed upon. Article 32 excluded clergy and the members of religious orders from political activities. Members of the clergy could join or remain in the NSDAP however without transgressing church discipline, - the ordinance of the Holy See forbidding priests to be members of a political party was never issued - and the Nazis declared that "the movement sustaining the state cannot be equated with the political parties of the parliamentary multi-party state in the sense of Article 32." [80]

- Effects of the concordat

Most historians consider the Reichskonkordat an important step toward the international acceptance of Adolf Hitler's Nazi regime.[81] Guenter Lewy, political scientist and author of The Catholic Church and Nazi Germany, wrote:

There is general agreement that the Concordat increased substantially the prestige of Hitler's regime around the world. As Cardinal Faulhaber put it in a sermon delivered in 1937: "At a time when the heads of the major nations in the world faced the new Germany with cool reserve and considerable suspicion, the Catholic Church, the greatest moral power on earth, through the Concordat expressed its confidence in the new German government. This was a deed of immeasurable significance for the reputation of the new government abroad.

The Catholic Church was not alone in signing treaties with the Nazi regime at this point. The concordat was preceded by the Four-Power Pact Hitler had signed in June 1933. After the signing of the treaty on 14 July, the Cabinet minutes record Hitler as saying that the concordat had created an atmosphere of confidence that would be "especially significant in the struggle against international Jewry." Controversial author John Cornwell offered this assessment of the dissolution of the Catholic Centre Party:[44]

The fact that the party voluntarily disbanded itself, rather than go down fighting, had a profound psychological effect, depriving Germany of the last democratic focus of potential noncompliance and resistance: In the political vacuum created by its surrender, Catholics in the millions joined the Nazi Party, believing that it had the support of the Pope. The German bishops capitulated to Pacelli's policy of centralization, and German Catholic democrats found themselves politically leaderless.

— John Cornwell

In the Reichskonkordat, the German government achieved a complete proscription of all clerical interference in the political field (articles 16 and 32). It also ensured the bishops' loyalty to the state by an oath and required all priests to be Germans and subject to German superiors. Restrictions were also placed on the Catholic organizations. In a two-page article in the L'Osservatore Romano on 26 July and 27 July, Cardinal Pacelli said that the purpose of the Reichskonkordat was:"not only the official recognition (by the Reich) of the legislation of the Church (its Code of Canon Law), but the adoption of many provisions of this legislation and the protection of all Church legislation."[citation needed] Pacelli told an English representative that the Holy See had only made the agreement to preserve the Catholic Church in Germany; he also expressed his aversion to anti-Semitism.[82]

- Violations

According to John Jay Hughes, church leaders were realistic about the Concordat’s supposed protections.[83] Cardinal Faulhaber is reported to have said: "With the concordat we are hanged, without the concordat we are hanged, drawn and quartered."[citation needed] In Rome the Vatican secretary of state, Cardinal Pacelli (later Pius XII), told the British minister to the Holy See that he had signed the treaty with a pistol at his head. Hitler was sure to violate the agreement, Pacelli said — adding with gallows humor that he would probably not violate all its provisions at once.[83]

When the Nazi government violated the concordat (in particular article 31), German bishops and the Holy See protested against these violations. Between September 1933 and March 1937 Pacelli issued over seventy notes and memoranda protesting such violations. When Nazi violations of the Reichskonkordat escalated to include physical violence, Pope Pius XI issued the 1937 encyclical Mit brennender Sorge.[84][85] quotation "Violence had been used against a Catholic leader as early as June 1934, in the 'Night of the Long Knives' ... by the end of 1936 physical violence was being used openly and blatantly against the Catholic Church.

Impact of the Spanish Civil War on Nazi-Catholic relations

The Spanish Civil War (1936–39) saw Nationalists (aided by Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany) and Republicans (aided by the Soviet Union, Mexico - as well as International Brigades of volunteers, most of whom were under the command of the Comintern). The Republican president, Manuel Azaña, was anticlerical, while the Nationlist Generalissimo Francisco Franco, established a longstanding Fascist dictatorship which restored some privileges to the Church.[86] According to Hitler's Table Talk, Hitler believed that Franco's accommodation of the church was an error: "one makes a great mistake if one thinks that one can make a collaborator of the Church by accepting a compromise. The whole international outlook and political interest of the Catholic Church in Spain render inevitable conflict between the Church and Franco regime".[87]

The Nazis portrayed the war as a contest between civilization and Bolshevism. According to historian, Beth Griech-Polelle, many church leaders "implicitly embraced the idea that behind the Republican forces stood a vast Judeo-Bolshevik conspiracy intent on destroying Christian civilization." [88] Joseph Goebbels' Ministry of Propaganda served as the main source of German domestic coverage of the war. Goebbels, like Hitler, frequently mentioned the so-called link between jewishness and communism. Goebbels instructed the press to call the Republican side simply Bolsheviks - and not to mention German military involvement. Bolshevism was pathological criminal nonsense, demonstrably thought up by Jews. In Salamanca, Willi Kohn, German propaganda attaché, played up the war as a crusade to sweep away Judeo-Bolshevism.

Against this backdrop, in August 1936, the German bishops met for their annual conference at Fulda. The bishops produced a joint pastoral letter regarding the Spanish Civil War: "Therefore, German unity should not be sacrificed to religious antagonism, quarrels, contempt, and struggles. Rather our national power of resistance must be increased and strengthened so that not only may Europe be freed from Bolshevism by us, but also that the whole civilized world may be indebted to us." Nuncio Cesare Orsenigo arranged for Cardinal Faulhaber to have a private meeting with Hitler.[89] On November 4, 1936, over three hours Hitler told Faulhaber that religion was critical for the state, that his goal was to protect the German people from congenitally afflicted criminals such as now wreak havoc in Spain. Faulhaber replied that the Church would "not refuse the state the right to keep these pests away from the national community within the framework of moral law." [90] Kershaw cites the meeting as an example of Hitler's ability to "pull the wool over the eyes even of hardened critics" for "Faulhaber - a man of sharp acumen, who had often courageously criticized the Nazi attacks on the Catholic Church - went away convinced that Hitler was deeply religious".[91]

On November 18, Faulhaber met with leading members of the German hierarchy of cardinals to ask them to remind parishioners of the errors of communism outlined in Leo XIII's 1891 encyclical Rerum Novarum. On November 19, Pius XI announced that communism had moved to the head of the list of "errors" and that a clear statement was needed.[92] On November 25 Faulhaber told the Bavarian bishops that he had promised Hitler the bishops would issue a new pastoral letter in which they condemned "Bolshevism which represents the greatest danger for the peace of Europe and the Christian civilization of our country".[90] In addition, he stated, the pastoral letter "will once again affirm our loyalty and positive attitude, demanded by the Fourth Commandment, toward todays form of government and the Fuhrer. "[93]

On December 24, 1936 the German joint hierarchy ordered its priests to read the pastoral letter, entitled On the Defense against Bolshevism, from all their pulpits on January 7, 1937. The letter included the statement : "the fateful hour has come for our nation and for the Christian culture of the western world - the Fuhrer and Chancellor Adolf Hitler saw the march of Bolshevism from afar and turned his mind and energies towards averting this enormous danger from the German people and the whole western world. The German bishops consider it their duty to do their utmost to support the leader of the Reich with every available means in this defense." Hitler's promise to Faulhaber, to clear up small problems between the Catholic Church and the Nazi state, never did materialize. Faulhaber, Galen, and Pius XI, continued to oppose Communism throughout their tenure as anxieties reached a highpoint in the 1930's with what the Vatican termed the 'red triangle', formed by the USSR, Republican Spain and revolutionary Mexico. They followed a series of encyclicals - Bona sana (1920), Miserentissimus redemtor (1928), Caritate Christi compusli (1932) and most importantly Divini redemptoris (1937) - all of which condemned communism.[94]

Deteriorating relationship with the Nazi regime

Anti-Nazi sentiment grew in Catholic circles as the Nazi government increased its repressive measures against their activities.[35] Appearing before 250,000 pilgrims at Lourdes in April 1935, Cardinal Pacelli said:

[The Nazis] are in reality only miserable plagiarists who dress up old errors with new tinsel. It does not make any difference whether they flock to the banners of the social revolution, whether they are guided by a false conception of the world and of life, or whether they are possessed by the superstition of a race and blood cult.[95]

In 1936, Archbishop Cesare Orsenigo, Papal Nuncio to Germany, asked Cardinal Pacelli, then Vatican Secretary of State, for instructions regarding an invitation from Hitler to attend a Nazi Party meeting in Nuremberg, along with the entire diplomatic corps. Pacelli replied, ”The Holy Father thinks it is preferable that your Excellency abstain, taking a few days’ vacation.” In 1937, Orsenigo was invited along with the diplomatic corps to a reception for Hitler’s birthday. Orsenigo again asked the Vatican if he should attend. Pacelli’s reply was, “The Holy Father thinks not. Also because of the position of this Embassy, the Holy Father believes it is preferable in the present situation if your Excellency abstains from taking part in manifestations of homage toward the Lord Chancellor." During Hitler’s visit to Rome in 1938, Pius XI and Pacelli avoided meeting with him by leaving Rome a month early for the papal summer residence of Castel Gandolfo. The Vatican was closed, and the priests and religious brothers and sisters left in Rome were told not to participate in the festivities and celebrations surrounding Hitler’s Visit. On the Feast of the Holy Cross, Pius XI said from Castel Gandolfo, “It saddens me to think that today in Rome the cross that is worshipped is not the Cross of our Saviour.”

Persecution of German Catholics

German Catholics met the Nazi takeover with apprehension, as leading clergymen had been warning against Nazism for years.[64] A threatening, though initially mainly sporadic persecution of the Catholic Church in Germany commenced.[65] "By the latter part of the decade of the Thirties", wrote Phayer, "church officials were well aware that the ultimate aim of Hitler and other Nazis was the total elimination of Catholicism and of the Christian religion. Since the overwhelming majority of Germans were either Catholic or Protestant this goal had to be a long-term rather than a short-term Nazi objective".[97]

Hitler moved quickly to eliminate Political Catholicism. The Nazis arrested thousands of members of the German Catholic Centre Party, as well as Catholic clergymen and closed Catholic schools and institutions.[39] 2000 functionaries of the Bavarian People's Party were rounded up by police in late June 1933, and it, along with the national Catholic Centre Party, ceased to exist in early July. Vice Chancellor Papen meanwhile negotiated a Reich Concordat with the Vatican, which prohibited clergy from participating in politics.[71] Kershaw wrote that the Vatican was anxious to reach agreement with the new government, despite "continuing molestation of Catholic clergy, and other outrages committed by Nazi radicals against the Church and its organisations".[72]

In Hitler's bloody night of the long knives purge of 1934, Erich Klausener, the head of Catholic Action, was assassinated by the Gestapo.[98] The Nazi Government closed down Catholic publications, dissolved the Catholic Youth League and charged thousands of priests, nuns and lay leaders on trumped up charges. The Gestapo violated the sanctity of the confessional to obtain information.[99] Church kindergartens were closed, crucifixes were removed from schools, the Catholic press was closed down and Catholic welfare programs were restricted on the basis they assisted the "racially unfit". Parents were coerced into removing their children from Catholic schools. In Bavaria, teaching positions formerly allotted to nuns were awarded to secular teachers and denominational schools transformed into "Community schools".[100]

Once Hitler had obtained full power, he sometimes allowed pressure to be placed on German parents to remove children from religious classes to be given ideological instruction in its place, while in elite Nazi schools, Christian prayers were replaced with Teutonic rituals and sun-worship.[12]

1935-6 was the height of the "immorality" trials against priests, monks, lay-brothers and nuns. In the United States, protests were organised in response to the sham trials, including a June 1936, petition signed by 48 clergymen, including rabbis and Protestant pastors: "We lodge a solemn protest against the almost unique brutality of the attacks launched by the German government charging Catholic clergy with gross immorality... in the hope that the ultimate suppression of all Jewish and Christian beliefs by the totalitarian state can be effected."[101]

Intimidation of clergy was widespread. Cardinal Faulhaber was shot at. Cardinal Innitzer had his Vienna residence ransacked in October 1938 and Bishop Sproll of Rottenburg was jostled and his home vandalised. In 1937, the New York Times reported that Christmas would see "several thousand Catholic clergymen in prison." Propaganda satirized the clergy, including Anderl Kern's play The Last Peasant.[102]

Many German clergy were sent to the concentration camps for voicing opposition to the Nazi regime, or in some regions simply because of their faith; these included the pastor of Berlin's Catholic Cathedral Bernhard Lichtenberg and the seminarian Karl Leisner. Many Catholic laypeople also paid for their opposition with their life, including the mostly Catholic members of the Munich resistance group White Rose around Hans and Sophie Scholl.

In 1941 the Nazi authorities decreed the dissolution of all monasteries and abbeys in the German Reich, many of them effectively being occupied and secularized by the Allgemeine SS under Himmler. However, on July 30, 1941 the Aktion Klostersturm (Operation Monastery) was put to an end by a decree of Hitler, who feared the increasing protests by the Catholic part of German population might result in passive rebellions and thereby harm the Nazi war effort at the eastern front.[103] Over 300 monasteries and other institutions were expropriated by the SS.[104]

Catholic opposition inside Germany: 1933-1945

In the Nazi police state, the ability of the Church and its members to oppose Nazi policy was severely restricted. Following intimidation and thousands of arrests, the Bavarian People's Party and the Catholic Centre Party had ceased to exist by early July. Amidst widespread harassment of the clergy and Catholic organisations, the new government negotiated the Concordat with the Vatican, which prohibited clergy from participating in politics.[105] In 1935, when Protestant pastors read a protest statement from the pulpits of the small but growing Confessing churches, the Nazi authorities briefly arrested over 700 pastors. In 1937, the Gestapo confiscated copies of anti-Nazi papal encyclical Mit brennender Sorge from the Catholic diocesan offices throughout Germany.[35]

The position of open Catholic opposition to the Nazis decreased following the Concordat and Hitler's emergence as dictator of Germany. Following the Treaty, Catholics were free to join the Nazi Party, which many did. The Nazis arrested thousands of members of the German Catholic Centre Party, as well as Catholic clergymen and closed Catholic schools and institutions.[39]

Alan Bullock wrote that the Churches and the army were the only two institutions to retain some independence in Nazi Germany and "among the most courageous demonstrations of opposition during the war were the sermons preached by the Catholic Bishop of Munster and the Protestant Pastor, Dr Niemoller..." but that "Neither the Catholic Church nor the Evangelical Church, however, as institutions, felt it possible to take up an attitude of open opposition to the regime".[108] Bishop von Galen of Munster was among the German conservatives who had criticised Weimar Germany, and initially hoped the Nazi government might restore German prestige.[109] According to Griech-Polelle, he believed the Dolchstosslegende explained the German army's defeat in 1918.[110] But Galen quickly became disenchanted with the anti-Catholicism and racism of the Hitler regime, and emerged as an outspoken critic of Nazi racism and totalitarianism. From Easter 1934, he began publicly criticizing the Nazi government. He complained directly to Hitler of breaches of the Concordat and his protest against the removal of crucifixes from classrooms was followed by public demonstrations. In 1941, he denounced the lawlessness of the Gestapo, the confiscations of church properties and euthanasia in Nazi Germany.[111] His defiant sermons included this 1941 denunciation of the Gestapo:[49]

Many times, and again quite recently, we have seen the Gestapo arresting blameless and highly respected German men and women without the judgment of any court or any opportunity for defense, depriving them of their freedom, taking them away from their homes interning them somewhere. In recent weeks even two members of my closest council, the chapter of our cathedral, have been suddenly seized from their homes by the Gestapo, removed from Munster and banished to distant places. -- Bishop August von Galen, homily, 1941

— Bishop August von Galen, homily, 1941

Documents suggest the Nazis intended to hang von Galen at the end of the war.[112] His speeches angered Hitler, who, according to Hitler's Table Talk, told confidantes in 1942: "The fact that I remain silent in public over Church affairs is not in the least misunderstood by the sly foxes of the Catholic Church, and I am quite sure that a man like Bishop von Galen knows full well that after the war I shall extract retribution to the last farthing".[16]

Cardinal Michael von Faulhaber had been a longstanding critic of Nazism. Following the Nazi takeover, he delivered three Advent sermons in 1933 that condemned the anti-Semitic propaganda of the Nazis. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, "Throughout his sermons until the collapse (1945) of the Third Reich, Faulhaber vigorously criticized Nazism, despite governmental opposition. Attempts on his life were made in 1934 and in 1938. He worked with American occupation forces after the war, and he received the West German Republic’s highest award, the Grand Cross of the Order of Merit.[113] Erich Klausener, the President of Catholic Action in Germany, delivered a speech to the Catholic Congress in June 1934, criticizing the regime. He was shot dead in his office on the Kristalnacht of June 30. His entire staff was sent to concentration camps.[49] Klausener had assisted former Catholic Centre Party member Franz von Papen (by now Hitler's non-Nazi Vice Chancellor) draft his 17 June Marburg speech which had denounced Nazi terror and the suppression of the free press and the church.[114] Papen's staff were murdered in the purge, but he himself escaped execution:[49]

The 1937 papal encyclical Mit brennender Sorge was part drafted by the German Cardinal Michael von Faulhaber, a critic of Nazism. The encyclical accused the Nazi government of "systematic hostility leveled at the Church", and criticised a range of Nazi actions and beliefs - notably racism.[115] Despite the efforts of the Gestapo to block its distribution, the church distributed thousands to the parishes of Germany. Hundreds were arrested for handing out copies, and Goebells increased anti-Catholic propaganda including a show trial of 170 Franciscans at Koblenz.[49]

Following the outbreak of war, conscientious objectors were executed for treason, as with the Blessed Franz Jagerstatter.[49] The Kreisau Circle was one of the few clandestine German opposition groups operating inside Nazi Germany, among its number were 2 Jesuit priests.[116] The Bavarian Catholic Count Claus Von Stauffenberg, was moved to oppose the regime in part by its oppression of the Church. In 1944, he led the 20 July plot (Operation Valkyrie) to assassinate Hitler .[117] The Church clashed with the Nazi regime over the implementation of a programme of euthanasia in Nazi Germany in the name of "racial hygiene". Prominent clergymen, including the Bishop of Munster, Clemens August Graf von Galen and Cardinal Bertram vocally denounced the policy.[25]

- "Euthanasia"

Hitler was in favour of killing those whom he judged to be "unworthy of life"From 1939, the regime began its program of euthanasia in Nazi Germany, which included the killing of children, and under which those deemed "racially unfit" were to be "euthanased". The mentally handicapped were taken from hospitals and homes and taken to gas chambers to be killed. August von Galen, the Bishop of Munster accused the government of breaking the law and publicly condemned the policy - saying that it was the duty of all Christians to oppose the taking of human life even it meant losing their own.[118] Fr Bernhard Lichtenberg protested the policy to the Nazis chief medical officer.[119] The regime took the program underground.[120]

Mit brennender Sorge

The Catholic Church officially condemned the Nazi theory of racism in Germany in 1937 with the Encyclical "Mit Brennender Sorge", signed by Pope Pius XI. Smuggled into Germany to avoid prior censorship and read from the pulpits of all German Catholic churches, it condemned Nazi ideology [121] as "insane and arrogant". It denounced the Nazi myth of "blood and soil", decried neopaganism of Nazism, its war of annihilation against the Church, and even described the Führer himself as a 'mad prophet possessed of repulsive arrogance.' Although there is some difference of opinion as to the impact of the document, it is generally recognized as the "first ... official public document to criticize Nazism". [124]

- Impact and consequences

According to Eamon Duffy "The impact of the encyclical was immense, and it dispelled at once all suspicion of a Fascist Pope."[125] quotation "In a triumphant security operation, the encyclical was smuggled into Germany, locally printed, and read from Catholic pulpits on Palm Sunday 1937. Mit Brennender Sorge ('With Burning Anxiety') denounced both specific government actions against the Church in breach of the concordat and Nazi racial theory more generally. There was a striking and deliberate emphasis on the permanent validity of the Jewish scriptures, and the Pope denounced the 'idolatrous cult' which replaced belief in the true God with a 'national religion' and the 'myth of race and blood'. He contrasted this perverted ideology with the teaching of the Church in which there was a home 'for all peoples and all nations'. The impact of the encyclical was immense, and it dispelled at once all suspicion of a Fascist Pope. While the world was still reacting, however, Pius issued five days later another encyclical, Divini Redemptoris denouncing Communism, declaring its principles 'intrinsically hostile to religion in any form whatever', detailing the attacks on the Church which had followed the establishment of Communist regimes in Russia, Mexico and Spain, and calling for the implementation of Catholic social teaching to offset both Communism and 'amoral liberalism'. The language of Divini Redemptoris was stronger than that of Mit Brennender Sorge, its condemnation of Communism even more absolute than the attack on Nazism. The difference in tone undoubtedly reflected the Pope's own loathing of Communism as the ultimate enemy. The last year of his life, however, left no one any doubt of his total repudiation of the right-wing tyrannies in Germany and, despite his instinctive sympathy with some aspects of Fascism, increasingly in Italy also. His speeches and conversations were blunt, filled with phrases like 'stupid racialism', 'barbaric Hitlerism'."

The "infuriated" Nazis increased their persecution of Catholics and the Church[126] by initiating a "long series" of persecution of clergy and other measures.[127][128] Gerald Fogarty asserts that "in the end, the encyclical had little positive effect, and if anything only exacerbated the crisis."[129] The American ambassador reported that it “had helped the Catholic Church in Germany very little but on the contrary has provoked the Nazi state...to continue its oblique assault upon Catholic institutions.”

- Nazi retaliation

Frank J. Coppa asserts that the encyclical was viewed by the Nazis as "a call to battle against the Reich" and that Hitler was furious and "vowed revenge against the Church".[130] Thomas Bokenkotter writes that, "the Nazis were infuriated, and in retaliation closed and sealed all the presses that had printed it and took numerous vindictive measures against the Church, including staging a long series of immorality trials of the Catholic clergy."[123]

The German police confiscated as many copies as they could and called it “high treason.” The Gestapo confiscated 12 printing presses that had printed the encyclical for distribution and the editors were arrested.[131] According to Owen Chadwick, the "infuriated" Nazis increased their persecution of Catholics and the Church.[132] According to John Vidmar, Nazi reprisals against the Church in Germany followed thereafter, including "staged prosecutions of monks for homosexuality, with the maximum of publicity".[133] Shirer reports that, "[d]uring the next years, thousands of Catholic priests, nuns and lay leaders were arrested, many of them on trumped-up charges of 'immorality' or 'smuggling foreign currency'."[134]

- The "Conspiracy of Silence"

While numerous German Catholics, who participated in the secret printing and distribution of Mit brennender Sorge, went to jail and concentration camps, the Western democracies remained silent, which Pope Pius XI labeled bitterly as "a conspiracy of silence".[135]

German Catholics and the Holocaust

Catholic bishops in Nazi Germany differed in their responses to the rise of Nazi Germany, World War II, and the Holocaust. In relations with the Nazi regime, figures like Cardinal Bertram, favoured a policy of concessions, while figures like Bishop Preysing of Berlin called for more concerted opposition.[136] According to Dr Harry Schnitker, Kevin Spicer's 2007 book Hitler's Priests found that around 0.5% of German priests (138 of 42,000) might be considered "brown priests" (Nazis). One such priest was Karl Eschweiler, an opponent of the Weimar Republic, who was suspended from priestly duties by Cardinal Pacelli (the future Pope Pius XII) for writing Nazi pamphlets in support of eugenics.[137]

Archbishop Konrad Gröber of Freiburg was known as the “Brown Bishop” because he was such an enthusiastic supporter of the Nazis. In 1933, he became a “sponsoring member” of the SS. In 1943, Grober expressed the opinion that bishops should remain loyal to the "beloved folk and Fatherland", despite abuses of the Reichskonkordat.[138] After the war, however, he claimed to have been such an opponent of the Nazis that they had planned to crucify him on the door for the Freiburg Cathedral.[citation needed] Bishop Wilhlem Berning of Osnabrück sat with the Protestant Deutsche Christen Reichsbishop in the Prussian State Council from 1933 to 1945, a clear signal of support for the Nazi regime.[citation needed] Cardinal Adolf Bertram ex officio head of the German episcopate also had some affinity for the Nazis. In 1933, for example, he refused to intervene on behalf of Jewish merchants who were the targets of Nazi boycotts, saying that they were a group “which has no very close bond with the church.”[citation needed] Bertram sent Hitler birthday greetings in 1939 in the name of all German Catholic bishops, an act that angered bishop Konrad von Preysing.[138] Bertram was the leading advocate of accommodation as well as the leader of the German church, a combination that reigned in other would-be opponents of Nazism.[138] Bishop Buchberger of Regensburg called Nazi racism directed at Jews “justified self-defense” in the face of “overly powerful Jewish capital.”[citation needed] Bishop Hilfrich of Limburg said that the true Christian religion “made its way not from the Jews but in spite of them.”[citation needed] Bishops von Preysing and Frings were the most public in the statements against genocide.[139]

According to Phayer, "no other German bishops spoke as pointedly as Preysing and Frings" against the regime.[139] In 1935, Pope Pius XI appointed Konrad von Preysing as Bishop of Berlin, the German capital. Von Preysing was a noted critic of Nazism. Like all other German bishops, including the nationalist Cardinal Bertram, Preysing openly denounced Nazi eugenics. Von Preysing's cathedral administrator, Bernard Lichtenberg, a priest recognised as Righteous among the Nations, was provost of the Cathedral of St Hedwig during Kristallnacht. After this notorious pogrom, Lichtenberg began to close each evening mass with a prayer for "the Jews and the other poor prisoners in the concentration camps" and protesting other Nazi policies. Sentenced to Dacau concentration Camp, he died en route.[140] The two men established the Hilfswerke beim Bischöflichen Ordinariat Berlin as an aid organization and through this assisted Jews. Preysing also assisted in drafting the anti-Nazi encyclical Mit Brennender Sorge and, together with Cologne’s Archbishop, Josef Frings, sought to have the German Bishops conference speak out against the Nazi death camps. Preysing even infrequently attended meetings of the Kreisau Circle German resistance movement.[141] The Kreisau Circle was one of the few clandestine German opposition groups operating inside Nazi Germany, among its number were 2 Jesuit priests.[142]

Cardinal Faulhaber became a prominent opponent of Nazism.[144] He delivered three Advent sermons in 1933 that condemned the anti-Semitic propaganda of the Nazis.[145] Entitled Judaism, Christianity, and Germany, the sermons affirmed the Jewish origins of the Christian religion, the continuity of the Old and New Testaments of the Bible, and the importance of the Christian tradition to Germany.[146]

Bishop von Galen of Munster, a conservative German nationalist, quickly became disenchanted with the Nazi government for its racism and anti-Catholicism and emerged as a strong critic of the regime. He denounced the lawlessness of the Gestapo.[147]

In East Prussia, the Bishop of Ermland, Maximilian Kaller denounced Nazi eugenics and racism, pursued a policy of ethnic equality for his German, Polish and Lithuanian flock, and protected his Polish clergy and laypeople. Threatened by the Nazis, he applied for a transfer to be chaplain to a concentration camp. His request was denied by Cesare Orsenigo, a Papal Nuncio with some Fascist sympathies.[148]

During the war, the Fulda Conference of Bishops met annually in Fulda.[138] The issue of whether the bishops should speak out against the persecution of the Jews was debated at a 1942 meeting in Fulda.[149] The consensus was to "give up heroic action in favor of small successes".[149] A draft letter proposed by Margarete Sommer was rejected, because it was viewed as a violation of the Reichskonkordat to speak out on issues not directly related to the church.[149]

Knowledge of the Holocaust

According to historians David Bankier and Hans Mommsen a thorough knowledge of the Holocaust was well within the reach of the German bishops, if they wanted to find out.[150] According to historian Michael Phayer, "a number of bishops did want to know, and they succeeded very early on in discovering what their government was doing to the Jews in occupied Poland".[151] Wilhelm Berning, for example, knew about the systematic nature of the Holocaust as early as February 1942, only one month after the Wannsee Conference.[151] Most German Church historians believe that the church leaders knew of the Holocaust by the end of 1942, knowing more than any other church leaders outside the Vatican.[152]

US Envoy Myron C. Taylor passed a US Government memorandum to Pius XII on 26 September 1942, outlining intelligence received from the Jewish Agency for Palestine which said that Jews from across the Nazi Empire were being systematically "butchered". Taylor asked if the Vatican might have any information which might tend to "confirm the reports", and if so, what the Pope might be able to do to influence public opinion against the "barbarities".[153] Cardinal Maglione handed Harold Tittman a response to a letter from Taylor regarding the mistreatment of Jews on 10 October. The note thanked Washington for passing on the intelligence, and confirmed that reports of severe measures against the Jews had reached the Vatican from other sources, though it had not been possible to "verify their accuracy". Nevertheless, "every opportunity is being taken by the Holy See, however, to mitigate the suffering of these unfortunate people".[154] The Pope raised race murders in his 1942 Christmas Radio Address. However, after the war, some bishops, including Adolf Bertram and Conrad Grober claimed that they had not been aware of the extent and details of the Holocaust, and were unsure of the veracity of the information that was brought to their attention.[152]

Papal Condemnations of anti-Semitism

Pius XI asserted to a group of pilgrims that antisemitism is incompatible with Christianity:[155]

"Mark well that in the Catholic Mass, Abraham is our Patriarch and forefather. Anti-Semitism is incompatible with the lofty thought which that fact expresses. It is a movement with which we Christians can have nothing to do. No, no, I say to you it is impossible for a Christian to take part in anti-Semitism. It is inadmissible. Through Christ and in Christ we are the spiritual progeny of Abraham. Spiritually, we are all Semites.

Catholic Church in the Nazi Empire

Czechoslovakia