British expedition to Tibet: Difference between revisions

was more than just the monastery at Naini |

put the para back about tactics - its a kind of summing up at this point i suppose so may be useful |

||

| Line 76: | Line 76: | ||

By now the Commander-in-Chief in India, [[Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener|Lord Kitchener]], was determined to see that Brigadier-General Macdonald should henceforth be in charge of the Mission at all times. The feeling in Simla was that Younghusband was unduly eager to head straight for Lhasa. Younghusband set out for New Chumbi on 6 June and telegraphed Louis Dane, the head of Curzon's Foreign Department telling him that "we are now fighting the Russians, not the Tibetans. Since Karo La we are dealing with Russia." He further sent off a stream of letters and telegrams claiming there was overwhelming evidence of the Tibetans relying on Russian support and that they were receiving a very substantial amount of it. These were claims with no foundation. Younghusband was ordered by Lord Ampthill, as acting Viceroy, to re-open negotiations and try again to communicate with the Dalai Lama. Reluctantly Younghusabnd did deliver an ultimatum in two letters, one adressed to the Dalai Lama and one to the Chinese amban, [[Manchu]] Resident in Lhasa, Yu-t'ai, though, as he wrote to his sister, he was against this course of action for he saw it as "giving them another chance of negotiating". On 10 June Younghusband arrived at New Chumbi. Macdonald and Younghusband discussed their differences, and on 12 June the Tibet Field Force marched out of New Chumbi. |

By now the Commander-in-Chief in India, [[Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener|Lord Kitchener]], was determined to see that Brigadier-General Macdonald should henceforth be in charge of the Mission at all times. The feeling in Simla was that Younghusband was unduly eager to head straight for Lhasa. Younghusband set out for New Chumbi on 6 June and telegraphed Louis Dane, the head of Curzon's Foreign Department telling him that "we are now fighting the Russians, not the Tibetans. Since Karo La we are dealing with Russia." He further sent off a stream of letters and telegrams claiming there was overwhelming evidence of the Tibetans relying on Russian support and that they were receiving a very substantial amount of it. These were claims with no foundation. Younghusband was ordered by Lord Ampthill, as acting Viceroy, to re-open negotiations and try again to communicate with the Dalai Lama. Reluctantly Younghusabnd did deliver an ultimatum in two letters, one adressed to the Dalai Lama and one to the Chinese amban, [[Manchu]] Resident in Lhasa, Yu-t'ai, though, as he wrote to his sister, he was against this course of action for he saw it as "giving them another chance of negotiating". On 10 June Younghusband arrived at New Chumbi. Macdonald and Younghusband discussed their differences, and on 12 June the Tibet Field Force marched out of New Chumbi. |

||

Once the obstacle of Gyantse Dong was cleared, the road to Lhasa would be open. Gyantse Dzong was, however, too strong for a small raiding force to capture, and as it overlooked British supply routes, it became the primary target of Macdonald's army. On 26 June, the final obstacle to the assault was cleared when a fortified monastery at Naini which covered the approach was taken in [[house to house fighting]] by the Gurkhas and |

Once the obstacle of Gyantse Dong was cleared, the road to Lhasa would be open. Gyantse Dzong was, however, too strong for a small raiding force to capture, and as it overlooked British supply routes, it became the primary target of Macdonald's army. On 26 June, the final obstacle to the assault was cleared when a fortified monastery at Naini which covered the approach was taken in [[house to house fighting]] by the Gurkhas and 40th Pathan soldiers. Further, Tibetan forces in two forts in the village were caught 'between two fires' as the garrison at Changlo Manor joined the fight. <ref> Charles Allen, p.201</ref> |

||

Tibetan responses to the invasion so far had comprised almost entirely static defences and sniping from the mountains at the passing column, neither tactic proving effective. Apart from the failed assault on Chang Lo two months previously, the Tibetans had not made any sallies against British positions. This attitude was born of a mix of justifiable fear of the Maxim Guns, and faith in the solid rock of their defences, yet in every battle they were disappointed, primarily by their poor weaponry and inexperienced officers. |

|||

===Storming of Gyantse Dzong=== |

===Storming of Gyantse Dzong=== |

||

Revision as of 20:42, 23 April 2013

| The British Military Expedition to Tibet | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

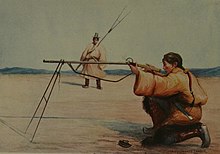

British and Tibetan officers negotiating. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Amban Thirteenth Dalai Lama | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

3,000 soldiers 7,000 support troops | Unknown, several thousand peasant conscripts | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

202 killed 411 other deaths | Unknown, several thousand | ||||||

The British expedition to Tibet during 1903 and 1904 was effectively an invasion of Tibet by British Indian forces under the auspices of the Tibet Frontier Commission, whose purported mission was to establish diplomatic relations and resolve the dispute over the border between Tibet and Sikkim.[1] In the nineteenth century, the British conquered Burma, Bhutan, and Sikkim, occupying the whole southern flank of Tibet, which remained the only Himalayan kingdom free of British influence.

The expedition was intended to counter Russia's perceived ambitions in the East and was initiated largely by Lord Curzon, the head of the British India government. Curzon had long obsessed over Russia's advance into Central Asia and now feared a Russian invasion of British India.[2] In April 1903, the British received clear assurance from the Russian government that it had no interest in Tibet. "In spite, however, of the Russian assurances, Lord Curzon continued to press for the dispatch of a mission to Tibet," a high level British political officer noted.[3] The expedition fought its way to Gyantse and eventually captured Lhasa, the heart of Tibet. The Dalai Lama fled to safety, first in Mongolia and later in China; but thousands of Tibetans armed with antiquated muzzle-loaders and swords were mown down by modern rifles and Maxim machine guns. The expedition forced remaining low-level Tibetan officials to sign the Great Britain and Tibet Convention (1904).[4] The mission was recognized as a military expedition by the British Indian government, "who issued a war medal for it."[5]

Background

The causes of the conflict are obscure - historian Charles Allen has called the official reasons for the invasion 'almost entirely bogus.'[6] It seems to have been provoked primarily by rumours circulating amongst the Calcutta-based British administration that the Chinese government, (who nominally ruled Tibet), were planning to give it to the Russians,[citation needed] thus providing Russia with a direct route to British India and breaking the chain of semi-independent, mountainous buffer-states which separated India from the Russian Empire to the north. These rumours were confirmed seemingly by the facts of Russian exploration of Tibet. Russian explorer Gombojab Tsybikov was the first photographer of Lhasa, residing in it during 1900—1901 with the aid of the thirteenth Dalai Lama's Russian courtier Agvan Dorjiyev. The Dalai Lama declined to have dealings with the British government in India and sent Dorjiyev in 1900 as an emissary to the court of Czar Nicholas II with an appeal for Russian protection. Dorjiyev was warmly received at the Peterhof and a year later, in 1901, at the Czar's palace in Yalta.

In view of these events Curzon's belief was reinforced that the Dalai Lama intended to place Tibet firmly within a sphere of Russian influence and end its neutrality.[7] In 1903 Viceroy, Lord Curzon, sent a request to the governments of China and Tibet for negotiations to be held at Khampa Dzong, a tiny Tibetan village north of Sikkim to establish trade agreements. The Chinese were willing, and ordered the thirteenth Dalai Lama to attend.[citation needed] However, the Dalai Lama refused, and also refused to provide transport to enable the amban, You Tai, to attend.[citation needed] Curzon concluded that China had no power or authority to compel the Tibetan government[citation needed], and gained approval from London to send the Tibet Frontier Commission, a military expedition led by Colonel Francis Younghusband, to Khampa Dzong.

On 19 July 1903, Younghusband arrived at Gangtok, the capital city of the Indian state of Sikkim, to prepare for his mission. A letter from the under-secretary to the government of India to Younghusband on 26 July 1903 stated that "In the event of your meeting the Dalai Lama, the government of India authorizes you to give him the assurance which you suggest in your letter." From August 1903 Younghusband and his escort commander at Khamba Jong, Lt-Col Herbert Brander, tried to provoke the Tibetans into a confrontation.[8] The British took a few months to prepare for the expedition which pressed into Tibetan territories in early December 1903 following an act of 'Tibetan hostility' - which was afterwards established by the British resident in Nepal to have been the herding of some trespassing Nepalese yaks and their drovers back across the border.[9] When Younghusband telegrammed the Viceroy, in an attempt to strengthen the British Cabinet's support of the invasion, that intelligence indicated Russian arms had entered Tibet, Curzon privately silenced him. 'Remember that in the eyes of HMG we are advancing not because of Dorjyev, or Russian rifles in Lhasa, but because of our Convention shamelessly violated, our frontier trespassed upon, our subjects arrested, our mission flouted, our representations ignored.'[10]

The entire British force, which had taken on all the characteristics of an invading army, numbered over 3,000 fighting men and was accompanied by 7,000 sherpas, porters and camp followers. Six companies of the 23rd Sikh Pioneers, and 4 companies of the 8th Gurkhas in reserve at Gnatong in Sikkim, as well as 2 Gurkha companies guarding the British camp at Khamba Jong were involved. The British authorities had thought of the difficulty of mountain fighting, and so dispatched a force with many Gurkha and Pathan troops, who were from mountainous regions. Permission for the operation was received from London, but it is not known whether the Balfour government was fully aware of the difficulty of the operation, or of the Tibetan intention to resist it.[citation needed]

The Tibetans were aware of the expedition. To avoid bloodshed the Tibetan general at Yadong pledged that if the British made no attack upon the Tibetans, he would not attack the British. Colonel Younghusband replied, on 6 December 1903, that "we are not at war with Tibet and that, unless we are ourselves attacked, we shall not attack the Tibetans".

When no Tibetan or Chinese officials met the British at Khapma Dzong, Younghusband advanced, with some 1,150 soldiers, 10,000 porters and labourers, and thousands of pack animals, to Tuna, fifty miles beyond the border. After waiting more months there, hoping in vain to be met by negotiators, the expedition received orders (in 1904) to continue toward Lhasa.[11]

Tibet's government, guided by the Dalai Lama was alarmed by the presence of a large acquisitive foreign power dispatching a military mission to its capital, and began marshalling its armed forces.

Initial advance

The British army which departed Gnatong in Sikkim on 11 December 1903 was well prepared for the coming conflict due to its lengthy experience of service in Indian border wars. The commander, Brigadier-General James Ronald Leslie Macdonald, wintered in the border country, using the time to train his troops near regular supplies of food and shelter before advancing properly in March, and making over 50 miles before his first major obstacle was presented on 31 March at the pass of Guru, near Lake Bhan Tso.

The massacre of Chumik Shenko

A military confrontation on 31 March 1904 became known as the Massacre of Chumik Shenko. Facing the vanguard of Macdonald's army and blocking the road was a Tibetan force of 3,000 armed with primitive matchlock muskets, ensconced behind a 5-foot-high (1.5 m) rock wall. On the slope above, the Tibetans had placed seven or eight sangars.[12] The Commissioner, Younghusband, was asked to stop but replied that the advance must continue, and that he could not allow any Tibetan troops to remain on the road. The Tibetans would not fight, but nor would they vacate their positions. Younghusband and Macdonald agreed 'the only thing to do was to disarm them and let them go'. This at least was the official version. The writer Charles Allen has also suggested that a dummy atrtack was played out in an effort to provoke the Tibetans into opening fire.[13]

It seems then that scuffles between the Sikhs and Tibetan guards grouped around Tibetan generals sparked an action of the Lhasa General - he fired a pistol hitting a Sikh in the jaw. British accounts insist that the Tibetan general became angry at the sight of the brawl developing and shot the Sikh soldier in the face prompting a violent response from the soldier's comrades which rapidly escalated the situation. Henry Newman, a reporter for Reuters, who described himself as an eye-witness, said that following this shot, the mass of Tibetans surged forward and their attack fell next on a correspondent for the Daily Mail, Edmund Candler, and that very soon after this fire was directed from three sides on the Tibetans crowded behind the wall. In Doctor Austine Waddell's account, "they poured a withering fire into the enemy, which, with the quick firing Maxims, mowed down the Tibetans in a few minutes with a terrific slaughter."[14] Second-hand accounts from the Tibetan side have asserted both that the British tricked the Tibetans into extinguishing the fuses for their matchlocks, and that the British opened fire without warning. However, no evidence exists to show such trickery took place and the likelihood is that the unwieldy weapons were of very limited use in the circumstances. Furthermore the British, Sikh and Gurkha soldiers closest to the Tibetans were nearly all protected by a high wall, and none were killed.[15]

The Tibetans were mown down by the Maxim guns as they fled. "I got so sick of the slaughter that I ceased fire, though the general’s order was to make as big a bag as possible," wrote Lieutenant Arthur Hadow, commander of the Maxim guns detachment. "I hope I shall never again have to shoot down men walking away."[16]

Half a mile from the battlefield the Tibetan forces reached shelter and were allowed to withdraw by Brigadier-General Macdonald. Behind them they left between 600 and 700 dead and 168 wounded, 148 of whom survived in British field hospitals as prisoners. British casualties were 12 wounded.[17] During this battle and some to follow, the Tibetans wore amulets which their lamas had promised would magically protect them from any harm. After one battle, surviving Tibetans showed profound confusion over the ineffectiveness of these amulets.[17] In a telegraph to his superior in India, the day after the massacre, Younghusband stated: "I trust the tremendous punishment they have received will prevent further fighting, and induce them to at last to negotiate."

The advance continues to Gyantse

Past the first barrier and with increasing momentum, Macdonald's force crossed abandoned defences at Kangma a week later, and on 9 April attempted to pass through Red Idol Gorge, which had been fortified to prevent passage. Macdonald ordered his Gurkha troops to scale the steep hillsides of the gorge and drive out the Tibetan forces ensconced high on their cliffs. This they began, but soon were lost in a furious blizzard, which stopped all communications with the Gurkha force. Some hours later, exploratory probes down the pass encountered shooting and a desultory exchange continued till the storm ended around noon, which showed that the Gurkhas had by chance found their way to a position above the Tibetan troops. Thus faced with shooting from both sides as Sikh soldiers pushed up the hill, the Tibetans moved back, again coming under severe fire from British artillery and retreated in good order, leaving behind 200 dead. British losses were again negligible.

Following this fight at the 'Red Idol Gorge', as the British later called it, the British military pressed on to Gyantse, reaching it on 11 April.[18] The town's gates were opened before Macdonald's forces, the garrison having already departed. Francis Younghusband wrote to his father; "As I have always said, the Tibetans are nothing but sheep." The townspeople continued with their business and the Westerners took a look at the monastic complex, the Palkor Chode. The central feature was the Temple of One Hundred Thousand Deities, a nine-storey stupa, modelled on the Mahabodhi Temple at Bodhgaya, the spot where Gautama Buddha first achieved enlightenment. [19] Statuettes and scrolls were shared out between officers. Younghusband's Mission Staff and Escort were billeted in the country mansion and farmyard of a Tibetan noble family named Changlo, and 'Changlo Manor' became the Mission Headquarters where Younghusband could hold his durbars and meet representatives of the Dalai Lama. In the words of historian Charles Allen, they now entered 'a halcyon period', even planting a vegetable garden at the Manor while officers explored the town unescorted, or went fishing and shooting. The Commission's medical officer, the philanthropic Captain Herbert Walton, attended to the needs of the local populace, notably performing operations to correct cleft palates, a particularly common affliction in Tibet. [20] Five days after he arrived at Gyantse, and deeming the defences of Changlo Manor secure, Macdonald ordered the main force to begin the march back to New Chumbi to protect the supply line.[21]

Younghusband wanted to move the Mission to Lhasa and telegraphed London for an opinion but got no reply. Reaction in Britain to the massacre at Chumik Shenko had been one of 'shock [and] growing disquiet'. The Spectator and Punch magazines had expressed views critical of a spectacle that included 'half-armed men' being wiped out 'with the irresistible weapons of science'. In Whitehall, the Cabinet 'kept its collective head down'. Meanwhile, intelligence reached Younghusband that Tibetan troops had gathered at Karo La, 45 miles east of Gyantse.[22]

Lt.Colonel Herbert Brander, Commander of the Mission Escort at Changlo Manor decided to strike against the Tibetan force assembling at Karo La without consulting Brigadier-General Macdonald, who was two days' riding away. Brander consulted Younghusband instead, who declared himself in favour of the action. Perceval Landon, correspondent of The Times who had sat in on the discussions observed that it was 'injudicious' to attack the Tibetans, and that it was 'quite out of keeping with the studious way in which we have hitherto kept ourselves in the right.' Brander's telegram setting out his plans reached Macdonald at New Chumbi on 3 May and he sought to reverse the action, but it was too late.[23] The battle at Karo La on 5-6 May is possibly the highest altitude action in history, won by Gurkha riflemen of the 8th Gurkhas and sepoys of the 32nd Sikh Pioneers who had climbed and then fought at an altitude in excess of 5,700 m. [24]

The Mission under siege

Meanwhile, an estimated 800 Tibetans attacked the Chang Lo garrison. The Tibetan war whoops gave the Mission staff time to form ranks and repulse the assailants, who lost 160 dead; three men of the Mission garrison were killed. An extravagant account of the attack, written by Lieutenant Leonard Bethell while faraway at New Chumbi, extolled Younghusband's heroism; in fact, Younghusband's own account revealed that he had fled to the Redoubt, where he remained under cover. The Gurkhas' light mountain guns and Maxims which would have been extremely useful in defending the fort, now back in Tibetan hands, had been requisitioned by Brander's Karo La party. Younghusband sent a message to Brander telling him to complete his attack on Karo, and only then to return to relieve the garrison. The unprovoked attack on the Mission and the Tibetans' reoccupation of the Gyantse Jong[25], though a shock, did in fact serve Younghusband's purpose. He wrote privately to Lord Curzon, "The Tibetans as usual have played into out hands." To Lord Ampthill in Simla he wrote that "His Majesty's Government must see that the necessity for going to Lhasa has now been proved beyond all doubt."[26]

Following the 5 May attack, the Mission and its garrison remained under constant fire from the Jong. The Tibetans weapons may have been inefficient and primitive but they kept up a constant pressure and fatalities were an irregular but nagging reality; a fatality on 6 May was followed by another eleven in the seven weeks after the surprise attack on Changlo Manor. The garrison responded with its own attacks; some of the Mounted Infantry returned from Karo La, armed with new standard issue Lee-Enfield rifles pursued Tibetan horsemen, and one of the Maxims was stationed on the roof and short bursts of machine-gun fire met targets as they appeared on the walls of the Jong. [27]

The attack on Changlo Manor seemed to spur the British and Indian Governments to renewed efforts and reinforcements were duly despatched. British troops stationed at Lebong, the 1st battalion of the Royal Fusiliers, the nearest British infantry available, were sent, as well as six companies of Indian troops from the 40th Pathans, a party from the 1st Battalion, the Royal Irish Rifles with two Maxim guns, a British Army Mountain Battery with four ten-pounder guns, and Murree Mountain Battery, as well as two Field Hospitals. Setting out on the 24 May 1904, the Royal Fusiliers joined up with Macdonald at New Chumbi, the base depot of the Tibet Mission, in the first days of June. [28]

Alarms and politics at Gyantse, and beyond

Significant alarms and actions during this period included fighting on the 18-19 May when attempts were made to take a building away from the Tibetans between the Jong and the Mission post, which were successful. About 50 Tibetans were gunned down and the building was re-named the Gurkha House. On 21 May Brander's fighters set out for the village of Naini, where the monastery and a small fort were occupied by the Tibetans and were involved in significant fighting but were required to break off to return to defend the Mission which was under concerted attack from the Jong - an attack stifled by Ottley's Mounted Infantry. It was Dapon Tailing's, the Tibetan commander of the garrison at Gyantse Jong, last serious attempt to take Changlo Manor. On 24 May a company of the 32nd Sikh pioneers arrived and Captain Seymour Shepard, DSO, 'a legend in the Indian Army' reached Gyantse, commanding a group of sappers, which lifted British morale. On 28 May he was involved in an attack on Palla Manor, 1000 yards east of Changlo Manor. 400 Tibetans were killed or wounded. No more assaults were contemplated at this point until Macdonald returned with more troops and Brander concentrated on strengthening the 3 positions; the Manor, the Gurka House and Palla Manor, and re-opened the line of communication with New Chumbi.

By now the Commander-in-Chief in India, Lord Kitchener, was determined to see that Brigadier-General Macdonald should henceforth be in charge of the Mission at all times. The feeling in Simla was that Younghusband was unduly eager to head straight for Lhasa. Younghusband set out for New Chumbi on 6 June and telegraphed Louis Dane, the head of Curzon's Foreign Department telling him that "we are now fighting the Russians, not the Tibetans. Since Karo La we are dealing with Russia." He further sent off a stream of letters and telegrams claiming there was overwhelming evidence of the Tibetans relying on Russian support and that they were receiving a very substantial amount of it. These were claims with no foundation. Younghusband was ordered by Lord Ampthill, as acting Viceroy, to re-open negotiations and try again to communicate with the Dalai Lama. Reluctantly Younghusabnd did deliver an ultimatum in two letters, one adressed to the Dalai Lama and one to the Chinese amban, Manchu Resident in Lhasa, Yu-t'ai, though, as he wrote to his sister, he was against this course of action for he saw it as "giving them another chance of negotiating". On 10 June Younghusband arrived at New Chumbi. Macdonald and Younghusband discussed their differences, and on 12 June the Tibet Field Force marched out of New Chumbi.

Once the obstacle of Gyantse Dong was cleared, the road to Lhasa would be open. Gyantse Dzong was, however, too strong for a small raiding force to capture, and as it overlooked British supply routes, it became the primary target of Macdonald's army. On 26 June, the final obstacle to the assault was cleared when a fortified monastery at Naini which covered the approach was taken in house to house fighting by the Gurkhas and 40th Pathan soldiers. Further, Tibetan forces in two forts in the village were caught 'between two fires' as the garrison at Changlo Manor joined the fight. [29]

Tibetan responses to the invasion so far had comprised almost entirely static defences and sniping from the mountains at the passing column, neither tactic proving effective. Apart from the failed assault on Chang Lo two months previously, the Tibetans had not made any sallies against British positions. This attitude was born of a mix of justifiable fear of the Maxim Guns, and faith in the solid rock of their defences, yet in every battle they were disappointed, primarily by their poor weaponry and inexperienced officers.

Storming of Gyantse Dzong

The Gyantse Dzong was a massively protected fortress; defended by the best Tibetan troops and the country's only artillery, it commanded a forbidding position high over the valley below. The British did not have time for a lengthy formal siege, so Macdonald proposed feints which would draw Tibetan soldiers away from the walls over several days. An artillery bombardment with mountain guns would then create a breach, which would be stormed immediately by his main force. This plan was implemented on 4 July, when Gurkha troops captured several batteries in the vicinity of the fortress by climbing vertical cliffs under fire, a feat they achieved with impressive frequency.

The eventual assault on 6 July did not happen as planned, as the Tibetan walls were stronger than expected. It took eleven hours to break through. The breach was not completed until 4:00 pm, by which time the assault had little time to succeed before nightfall. As Gurkhas and Royal Fusiliers charged the broken wall, they came under heavy fire and suffered some casualties. After several failed attempts to gain the walls, two soldiers broke through a bottleneck under fire despite both being wounded. They gained a foothold which the following troops exploited, enabling the walls to be taken. The Tibetans retreated in good order, allowing the British control of the road to Lhasa, but denying Macdonald a rout and thus remaining a constant threat (although never a serious problem) in the British rear for the remainder of the campaign.

The two soldiers who broke the wall at Gyantse Dzong were both well rewarded. Lieutenant John Duncan Grant was given the only Victoria Cross awarded during the expedition, whilst Havildar Pun received the Indian Order of Merit first class (equivalent to the VC as Indian soldiers were not eligible for VCs until the First World War).

Entry to Lhasa

Younghusband now assumed command of the mission, as the road had been cleared successfully. He took on his procession to Lhasa nearly 2,000 soldiers, all those not required to protect the road back to Sikkim.

Crossing several obviously fortified ambush points without incident and recrossing the Garo Pass, the force arrived in Lhasa on 3 August 1904 to discover that the thirteenth Dalai Lama had fled to Urga, the capital of Outer Mongolia. For this, the Chinese government stripped him of his titles and had their amban post notices around Lhasa that the Dalai Lama had been deposed, and that the amban was now in charge. However, Tibetans tore down the notices, and Tibetan officials ignored the amban. The amban escorted the British into the city with his personal guard, but informed them that he had no authority to negotiate with them. The Tibetans told them that only the absent Dalai Lama had authority to sign any accord, but Younghusband intimidated the regent, Ganden Tri Rinpoche, and any other local officials he could gather together as an ad hoc government, into signing a treaty drafted by himself, known subsequently as the Convention between Great Britain and Tibet (1904).

The Convention between Great Britain and Tibet (1904)

The salient points of the Convention were as follows:

- The British allowed to trade in Yadong, Gyantse, and Gartok.

- Tibet to pay a large indemnity (7,500,000 rupees, later reduced by two-thirds; the Chumbi Valley to be ceded to Britain until paid).

- Recognition of the Sikkim-Tibet border.

- Tibet to have no relations with any other foreign powers (effectively converting Tibet into a British protectorate).[30]

The regent commented that "When one has known the scorpion (meaning China) the frog (meaning Britain) is divine".

The amban later publicly repudiated the treaty, while Britain announced that it still accepted Chinese claims of authority over Tibet. Acting Viceroy Lord Ampthill reduced the indemnity by two thirds and considerably eased the terms in other ways. The provisions of this 1904 treaty were revised in the Anglo-Chinese Convention of 1906 signed between Britain and China.[31] The British, for a fee from the Qing court, also agreed "not to annex Tibetan territory or to interfere in the administration of Tibet", while China engaged "not to permit any other foreign state to interfere with the territory or internal administration of Tibet".[32][33][34]

Conclusion to the campaign

The British mission departed in late September 1904, after a ceremonial presentation of gifts. In the event, neither side could be too unhappy with the outcome of the war. Britain had "won" and had received the agreements it desired, but without actually receiving any tangible results. The Tibetans had lost the war but had seen China humbled in its failure to defend their client state from foreign incursion, and had pacified the invader by signing an unenforceable and largely irrelevant treaty. Captured Tibetan troops were all released without condition upon the war's conclusion, many after receiving medical treatment.

It was in fact the reaction in London which was fiercest in condemnation of the war. By the Edwardian period, colonial wars had become increasingly unpopular, and public and political opinion were unhappy with the waging of a war for such slight reasons as those provided by Curzon, and with the beginning battle, which was described in Britain as something of a deliberate massacre of unarmed men. It was only the support given to them by King Edward VII that provided Younghusband, Macdonald, Grant and others with the recognition they did eventually receive for what was quite a remarkable feat of arms in taking an army in such a remote, high-altitude location, driving through courageous defenders during freezing weather in difficult positions and achieving all their objectives in just six months, losing just 202 men to enemy action and 411 to other causes. Tibetan casualties have never been calculated.

Force composition

The composition of the opposing armies explains a lot about the outcome of the ensuing conflict. The Tibetan soldiers were almost all rapidly impressed peasants, who lacked organisation, discipline, training and motivation. Only a handful of their most devoted units, composed of monks armed usually with swords and jingals proved to be effective, and they were in such small numbers as to be unable to reverse the tide of battle. This problem was exacerbated by the generals who commanded the Tibetan forces, who seemed in awe of the British and refused to make any aggressive moves against the small and often dispersed convoy. They also failed conspicuously to properly defend their natural barriers to the British progress, frequently offering battle in relatively open ground instead, where Maxim Guns and rifle volleys caused great numbers of casualties.

By contrast, the British and Indian troops were experienced veterans of mountainous border warfare on the North-West Frontier, as was their commanding officer. Amongst the units at his disposal in his 3,000 strong force were elements of the 8th Gurkhas, 40th Pathans, 23rd and 32nd Sikh Pioneers, 19th Punjab Infantry and the Royal Fusiliers, as well as mountain artillery, engineers, Maxim gun detachments from four regiments and thousands of porters recruited from Nepal and Sikkim. With their combination of experienced officers, well-maintained modern equipment and strong morale, they were able to defeat the Tibetan armies at every encounter.

Aftermath

The Tibetans were not just unwilling to fulfil the treaty; they were also unable to perform many of its stipulations. Tibet did not have any substantial international trade commodities, and already accepted the borders with its neighbours. Nevertheless, the provisions of the 1904 treaty were confirmed by a 1906 treaty Anglo-Chinese Convention signed between Britain and China. The British, for a fee from the Qing court, also agreed "not to annex Tibetan territory or to interfere in the administration of Tibet", while China engaged "not to permit any other foreign state to interfere with the territory or internal administration of Tibet".[32][33]

In early 1910, Qing China sent a military expedition of its own to Tibet for direct rule. However, the Qing dynasty was overthrown in the Xinhai Revolution, which began in October 1911. Although the Chinese forces departed once more in 1913, the First World War and the Russian Revolution isolated Tibet, reducing Western influence and interest. In 1950, neither the British nor the newly-independent Indians were able or willing to resist the return of Chinese forces.

The position of British Trade Agent at Gyangzê was occupied from 1904 until 1944. It was not until 1937, with the creation of the position of "Head of British Mission Lhasa", that a British officer had a permanent posting in Lhasa itself.[35]

The British seem to have misread the military and diplomatic situation for the Russians did not have the designs on India that the British foresaw and the campaign was politically redundant before it began. It had however, "a profound effect upon Tibet, changing it forever, and for the worse at that, doing much to contribute to Tibet's loss of innocence."[36]

Subsequent interpretations

Chinese historians write of Tibetans heroically opposing the British out of loyalty not to Tibet, but to China.[clarification needed] They assert that the British troops looted and burned, that the British interest in trade relations was a pretext for annexing Tibet, a step toward the ultimate goal of annexing all of China; but that the Tibetans destroyed the British forces, and that Younghusband escaped only with a small retinue.[37] The Chinese government has turned Gyantze Dzong into a "Resistance Against the British Museum" promoting these views, as well as other themes such as the brutal life endured by Tibetan serfs who fiercely loved their Chinese mother country.[38] China also treats the invasion as part of the its "century of humiliation" at the hands of Western and Japanese powers and the defence as a Chinese resistance, while many Tibetans look back to it as an exercise of Tibetan self-defence and an act of independence from the Qing dynasty as the dynasty was falling apart.[39]

See also

- Perceval Landon

- Sikkim Expedition

- Red River Valley, a 1997 Chinese movie about the events of the British expedition to Tibet

- Category:British military personnel of the British expedition to Tibet

Notes

- ^ Landon, P. (1905). The Opening of Tibet Doubleday, Page & Co., New York.

- ^ Charles Allen, Duel in the Snows, John Murray 2004, p.1

- ^ Charles Bell (1992). Tibet Past and Present. CUP Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 66. ISBN 81-208-1048-1. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ^ Convention Between Great Britain and Tibet (1904)

- ^ Charles Bell (1992). Tibet Past and Present. CUP Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 68. ISBN 81-208-1048-1. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ^ Duel in the Snows, Charles Allen, p.1

- ^ Charles Allen, Duel in the Snows, p.2 John Murray 2004

- ^ Charles Allen, Duel in the Snows, p.28

- ^ Charles Allen, p.31

- ^ Allen, p.33

- ^ Powers (2004), p. 80.

- ^ Fleming (1961); p. 146

- ^ Charles Allen, p.113

- ^ Charles Allen, Duel in the Snows'. pp 111-120

- ^ Charles Allen, p.120

- ^ Virtual Tibet: Searching for Shangri-La from the Himalayas to Hollywood, page 195

- ^ a b Powers (2004), p. 81

- ^ Allen, p.137

- ^ Allen, p.141

- ^ Plarr, V. (1938). Plarr's Lives of the Fellows of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. Vol. 3, p. 815. Royal College of Surgeons, London.

- ^ Allen, p.149

- ^ Charles Allen, p.156

- ^ Charles Allen, p.157-159

- ^ Charles Allen, p.176

- ^ Charles Allen, p.163

- ^ Charles Allen, p.177

- ^ Charles Allen, p.186

- ^ Charles Allen, p.185

- ^ Charles Allen, p.201

- ^ Powers 2004, pg. 82

- ^ Anglo-Chinese Convention

- ^ a b Convention Between Great Britain and China Respecting Tibet (1906) Cite error: The named reference "treaty1906" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Bell, 1924, p. 288.

- ^ Powers 2004, pp. 82-3

- ^ McKay, 1997, pp. 230–1.

- ^ Martin Booth, review of Charles Allen, Duel in the Snows, The Sunday Times.

- ^ Powers 2004, pp. 84-9

- ^ Powers 2004, pg. 93

- ^ "China Seizes on a Dark Chapter for Tibet", by Edward Wong, The New York Times, 9 August 2010 (10 August 2010 p. A6 of NY ed.). Retrieved 10 August 2010.

Bibliography

- Allen, Charles . Duel in the Snows:The True Story of the Younghusband Mission to Lhasa; J.Murray

- Bell, Charles Alfred. Tibet: Past & present (1924) Oxford University Press ; Humphrey Milford.

- Candler, Edmund (1905) The Unveiling of Lhasa. New York; London: Longmans, Green, & Co; E. Arnold

- Carrington, Michael (2003) "Officers, Gentlemen and Thieves: the looting of monasteries during the 1903/4 Younghusband Mission to Tibet", in: Modern Asian Studies; 37, 1 (2003), pp. 81–109

- Fleming, Peter (1961) Bayonets to Lhasa London: Rupert Hart-Davis (reprinted by Oxford U.P., Hong Kong, 1984 ISBN 0-19-583862-9)

- French, Patrick (1994) Younghusband: the Last Great Imperial Adventurer. London: HarperCollins ISBN 0-00-637601-0

- Herbert, Edwin (2003) Small Wars and Skirmishes, 1902-18: early twentieth-century colonial campaigns in Africa, Asia, and the Americas. Nottingham: Foundry Books ISBN 1-901543-05-6

- Hopkirk, Peter (1990) The Great Game: on secret service in high Asia. London: Murray (Reprinted by Kodansha International, New York, 1992 ISBN 1-56836-022-3; as: The Great Game: the struggle for empire in central Asia)

- McKay, Alex (1997). Tibet and the British Raj: The Frontier Cadre 1904–1947. London: Curzon. ISBN 0-7007-0627-5.

- Powers, John (2004) History as Propaganda: Tibetan exiles versus the People's Republic of China. Oxford University Press ISBN 978-0-19-517426-7

- Gordon T. Stewart: Journeys to Empire . Enlightenment, Imperialism, and the British Encounter with Tibet 1774 - 1904, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2009 ISBN 978-0-521-73568-1

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)

External links

- "No. 27743". The London Gazette (invalid

|supp=(help)). 13 December 1904. Macdonald's official report

- Use dmy dates from December 2010

- Wars involving Tibet

- Conflicts in 1903

- Conflicts in 1904

- Wars involving British India

- Wars involving the United Kingdom

- 20th-century military history of the United Kingdom

- 1903 in Asia

- 1904 in Asia

- 1903 in China

- 1904 in China

- Invasions

- Military expeditions

- Expeditions from the United Kingdom

- 1900s in Tibet

- Expeditions from India