Binturong: Difference between revisions

BhagyaMani (talk | contribs) →Ecology and behavior: revised + extended with refs |

BhagyaMani (talk | contribs) →Characteristics: extended with ref |

||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

[[Thomas Stamford Raffles]] first described a specimen from [[Malacca]], where it is called binturong.<ref name=Raffles>Raffles, T. S. (1822). [http://archive.org/stream/mobot31753002433594#page/253/mode/2up ''XVII. Descriptive Catalogue of a Zoological Collection, made on account of the Honourable East India Company, in the Island of Sumatra and its Vicinity, under the Direction of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, Lieutenant-Governor of Fort Marlborough', with additional Notices illustrative of the Natural History of those Countries'']. The Transactions of the Linnean Society of London, Volume XIII: 239–274.</ref> |

[[Thomas Stamford Raffles]] first described a specimen from [[Malacca]], where it is called binturong.<ref name=Raffles>Raffles, T. S. (1822). [http://archive.org/stream/mobot31753002433594#page/253/mode/2up ''XVII. Descriptive Catalogue of a Zoological Collection, made on account of the Honourable East India Company, in the Island of Sumatra and its Vicinity, under the Direction of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, Lieutenant-Governor of Fort Marlborough', with additional Notices illustrative of the Natural History of those Countries'']. The Transactions of the Linnean Society of London, Volume XIII: 239–274.</ref> |

||

The binturong is a [[Monotypic taxon|monotypic]] [[Genus (biology)|genus]].<ref name=Pocock1939>Pocock, R. I. (1939). [http://www.archive.org/stream/PocockMammalia1/pocock1#page/n519/mode/2up ''The fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma. Mammalia. – Volume 1'']. Taylor and Francis, London. Pp. 431–439.</ref> |

The binturong is a [[Monotypic taxon|monotypic]] [[Genus (biology)|genus]].<ref name=Pocock1939>Pocock, R. I. (1939). [http://www.archive.org/stream/PocockMammalia1/pocock1#page/n519/mode/2up ''The fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma. Mammalia. – Volume 1'']. Taylor and Francis, London. Pp. 431–439.</ref> |

||

The binturong eats primarily [[fruit]], but has also been known to eat a wide range of animal matter as well. [[Deforestation]] has greatly reduced its numbers. It makes chuckling sounds when it seems to be happy and utters a high-pitched wail when annoyed. If it is cornered, it can fight viciously. The binturong can live over 20 years in [[captivity (animal)|captivity]]; one has been recorded to have lived almost 26 years.{{Citation needed|date=August 2008}} |

|||

==Characteristics== |

==Characteristics== |

||

| Line 32: | Line 30: | ||

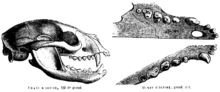

The body of the binturong is long and heavy, and low on the legs. It has a thick fur of strong black hair. The bushy and [[prehensile tail]] is thick at the root, gradually diminishing in size to the extremity, where it curls inwards. The muzzle is short and pointed, somewhat turned up at the nose, and is covered with bristly hairs, brown at the points, which lengthen as they diverge, and form a peculiar radiated circle round the face. The eyes are large, black and prominent. The ears are short, rounded, edged with white, and terminated by tufts of black hair. There are six short rounded incisors in each jaw, two canines, which are long and sharp, and six molars on each side. The hair on the legs is short and of a brownish tinge. The feet are five-toed, with large strong claws; the soles are bare, and applied to the ground throughout the whole of their length; the hind ones are longer than the fore.<ref name=Raffles/> |

The body of the binturong is long and heavy, and low on the legs. It has a thick fur of strong black hair. The bushy and [[prehensile tail]] is thick at the root, gradually diminishing in size to the extremity, where it curls inwards. The muzzle is short and pointed, somewhat turned up at the nose, and is covered with bristly hairs, brown at the points, which lengthen as they diverge, and form a peculiar radiated circle round the face. The eyes are large, black and prominent. The ears are short, rounded, edged with white, and terminated by tufts of black hair. There are six short rounded incisors in each jaw, two canines, which are long and sharp, and six molars on each side. The hair on the legs is short and of a brownish tinge. The feet are five-toed, with large strong claws; the soles are bare, and applied to the ground throughout the whole of their length; the hind ones are longer than the fore.<ref name=Raffles/> |

||

In general build the binturong is essentially like ''[[Paradoxurus]]'' and ''[[Paguma]]'' but more massive in the length of the tail, legs and feet, in the structure of the [[scent gland]]s and larger size of [[rhinarium]], which is more convex with a median groove being much narrower above the [[philtrum]]. The contour hairs of the coat are much longer and coarser, and the long hairs clothing the whole of the back of the ears project beyond the tip as a definite tuft. The anterior [[Synovial bursa|bursa]] flap of the ears is more widely and less deeply emarginate. The tail is more muscular, especially at the base, and in colour generally like the body, but commonly paler at the base beneath. The body hairs are frequently partly whitish or buff, giving a speckled appearance to the pelage, sometimes so extensively pale that the whole body is mostly straw-coloured or grey, the young being often at all events paler than the adults, but the head is always closely speckled with grey or buff. The long mystacial [[vibrissae]] are conspicuously white, and there is a white rim on the summit of the otherwise black ear. The glandular area is whitish.<ref name=Pocock1939/> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | The binturong is sometimes compared to a [[bear]], but it is considerably smaller, being no larger than a small [[dog]]. It is, however, the largest living species of the ''Viverridae'', only rivaled by the [[African civet]]. Its average head-and-body length is usually between {{convert|60|and|97|cm|in|abbr=on}}, and weight typically ranges between {{convert|9|and|20|kg|lb|abbr=on}}, although some exceptional individuals have been known to weigh {{convert|23|kg|lb|abbr=on}} or more.<ref name="Hunter">Hunter, L. (2011) ''Carnivores of the World''. Princeton University Press, ISBN 9780691152288</ref> The tail can act as a fifth hand and is nearly as long as the animal's own length at {{convert|50|to|84|cm|in|abbr=on}}. Females are 20% larger than males.<ref>{{cite web|last=San Diego Zoo|title=Mammal: Binturong|url=http://www.sandiegozoo.org/animalbytes/t-binturong.html|publisher=Sandiegozoo.org|accessdate=6 August 2012}}</ref> |

||

==Distribution and habitat== |

==Distribution and habitat== |

||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

Five [[Radio telemetry|radio-collared]] binturongs in the [[Phiu Khieo Wildlife Sanctuary]] exhibited an arrhythmic activity dominated by [[crepuscular]] and nocturnal tendencies with peaks in the early morning and late evening. Reduced inactivity periods occurred from midday to late afternoon. They moved between {{convert|25|m|ft|abbr=on}} and {{convert|2698|m|ft|abbr=on}} daily in the dry season and increased their daily movement to {{convert|4143|m|ft|abbr=on}} in the wet season. Ranges sizes of males varied between {{convert|0.9|km2|sqmi|abbr=on}} and {{convert|6.1|km2|sqmi|abbr=on}}. Two males showed slightly larger ranges in the wet season. Their ranges overlapped between 30–70%.<ref>{{Cite journal |last = Grassman |first = L. I., Jr. |coauthors = M. E. Tewes, N. J. Silvy |title = Ranging, habitat use and activity patterns of binturong ''Arctictis binturong'' and yellow-throated marten ''Martes flavigula'' in north-central Thailand |journal = Wildlife Biology |volume = 11 |issue = 1 |pages = 49–57 |year = 2005 |url= http://www.wildlifebiology.com/Downloads/Article/489/En/grassman%20et%20al.pdf |doi = 10.2981/0909-6396(2005)11[49:RHUAAP]2.0.CO;2}}</ref> The average home range of a radio-collared female in the [[Khao Yai National Park]] was estimated at {{convert|4|km2|sqmi|abbr=on}}, and the one of a male at {{convert|4.5|to|20.5|km2|sqmi|abbr=on}}. <ref>Austin, S. C. (2002). ''Ecology of sympatric carnivores in the Khao Yai National Park, Thailand''. PhD thesis, Texas University.</ref> |

Five [[Radio telemetry|radio-collared]] binturongs in the [[Phiu Khieo Wildlife Sanctuary]] exhibited an arrhythmic activity dominated by [[crepuscular]] and nocturnal tendencies with peaks in the early morning and late evening. Reduced inactivity periods occurred from midday to late afternoon. They moved between {{convert|25|m|ft|abbr=on}} and {{convert|2698|m|ft|abbr=on}} daily in the dry season and increased their daily movement to {{convert|4143|m|ft|abbr=on}} in the wet season. Ranges sizes of males varied between {{convert|0.9|km2|sqmi|abbr=on}} and {{convert|6.1|km2|sqmi|abbr=on}}. Two males showed slightly larger ranges in the wet season. Their ranges overlapped between 30–70%.<ref>{{Cite journal |last = Grassman |first = L. I., Jr. |coauthors = M. E. Tewes, N. J. Silvy |title = Ranging, habitat use and activity patterns of binturong ''Arctictis binturong'' and yellow-throated marten ''Martes flavigula'' in north-central Thailand |journal = Wildlife Biology |volume = 11 |issue = 1 |pages = 49–57 |year = 2005 |url= http://www.wildlifebiology.com/Downloads/Article/489/En/grassman%20et%20al.pdf |doi = 10.2981/0909-6396(2005)11[49:RHUAAP]2.0.CO;2}}</ref> The average home range of a radio-collared female in the [[Khao Yai National Park]] was estimated at {{convert|4|km2|sqmi|abbr=on}}, and the one of a male at {{convert|4.5|to|20.5|km2|sqmi|abbr=on}}. <ref>Austin, S. C. (2002). ''Ecology of sympatric carnivores in the Khao Yai National Park, Thailand''. PhD thesis, Texas University.</ref> |

||

[[Reginald Innes Pocock|Pocock]] observed the behaviour of several captive binturongs in the [[London Zoological Gardens]]. When resting they lie curled up, with the head tucked under the tail. They never leap, but climb skilfully, albeit slowly, progressing with equal ease and confidence along the upper side of branches or, upside down, beneath them, the prehensile tail being always in readiness as a help, and they descend the vertical bars of the cage head first, gripping them between their paws and using the prehensile tail as a check. When irritated they growl fiercely, and when on the prowl may periodically utter a series of low grunts or a hissing sound made by expelling the air through partially opened lips.<ref name=Pocock1939/> |

|||

They use the tail and claws to cling while searching for food. It can rotate its hind legs backwards so that its claws still have a grip when climbing down a tree head first.<ref name="Hunter"/> |

|||

The binturong also uses its tail to communicate, through the [[scent gland]]s on either side of the anus in both males and females. The females also possess paired scent glands on either side of the vulva.<ref>{{Cite journal | last = Story | first = H. E. | title = The External Genitalia and Perfume Gland in ''Arctictis binturong'' | journal = Journal of Mammalogy | volume = 26 | issue = 1 | pages = 64–66 | year = 1945 | doi = 10.2307/1375032}}</ref> The scent of binturong musk is often compared to that of warm buttered [[popcorn]]<ref name="sdz">{{cite web | work = Zoological Society of San Diego | title = Mammals: Binturong | url = http://www.sandiegozoo.org/animalbytes/t-binturong.html | accessdate = 2007-10-17}}</ref> and cornbread. The binturong brushes its tail against trees and howls to announce its presence to other binturongs. |

The binturong also uses its tail to communicate, through the [[scent gland]]s on either side of the anus in both males and females. The females also possess paired scent glands on either side of the vulva.<ref>{{Cite journal | last = Story | first = H. E. | title = The External Genitalia and Perfume Gland in ''Arctictis binturong'' | journal = Journal of Mammalogy | volume = 26 | issue = 1 | pages = 64–66 | year = 1945 | doi = 10.2307/1375032}}</ref> The scent of binturong musk is often compared to that of warm buttered [[popcorn]]<ref name="sdz">{{cite web | work = Zoological Society of San Diego | title = Mammals: Binturong | url = http://www.sandiegozoo.org/animalbytes/t-binturong.html | accessdate = 2007-10-17}}</ref> and cornbread. The binturong brushes its tail against trees and howls to announce its presence to other binturongs. |

||

| Line 72: | Line 72: | ||

===Reproduction=== |

===Reproduction=== |

||

The [[Estrous cycle|estrous period]] of the binturong is 81 days, with a [[gestation]] of 91 days.<ref name="wimmer">{{Cite journal | last = Wemmer | first = |

The [[Estrous cycle|estrous period]] of the binturong is 81 days, with a [[gestation]] of 91 days. The average age of [[sexual maturation]] is 30.4 months for females and 27.7 months for males. Fertility lasts until 15 years of age.<ref name="wimmer">{{Cite journal | last = Wemmer | first = C. | coauthors = J. Murtaugh | title = Copulatory Behavior and Reproduction in the Binturong, ''Arctictis binturong'' | journal = Journal of Mammalogy | volume = 62 | issue = 2 | pages = 342–352 |year= 1981|jstor=1380710 |doi = 10.2307/1380710}}</ref> The binturong is one of approximately 100 species of [[mammal]] believed by many husbandry experts to be capable of [[embryonic diapause]], or delayed implantation, which allows the female of the species to time [[childbirth|parturition]] to coincide with favorable environmental conditions. Typical birthing is of two offspring, but up to six may occur. |

||

The maximum known lifespan in captivity is thought to be over 25 years of age.<ref name="Macdonald">Macdonald, D.W. (2009). ''The Encyclopedia of Mammals''. Oxford University Press, Oxford.</ref> |

|||

==Threats== |

==Threats== |

||

Revision as of 13:19, 8 March 2013

| Binturong[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: | Arctictis Temminck, 1824

|

| Species: | A. binturong

|

| Binomial name | |

| Arctictis binturong (Raffles, 1822)

| |

| |

| Binturong range | |

The binturong (Arctictis binturong), also known as bearcat and Palawan binturong, is a viverrid found in South and Southeast Asia. It is uncommon or rare over much of its range and listed as Vulnerable by IUCN because of a population decline estimated to be more than 30% over the last 30 years.[2]

Thomas Stamford Raffles first described a specimen from Malacca, where it is called binturong.[3] The binturong is a monotypic genus.[4]

Characteristics

The body of the binturong is long and heavy, and low on the legs. It has a thick fur of strong black hair. The bushy and prehensile tail is thick at the root, gradually diminishing in size to the extremity, where it curls inwards. The muzzle is short and pointed, somewhat turned up at the nose, and is covered with bristly hairs, brown at the points, which lengthen as they diverge, and form a peculiar radiated circle round the face. The eyes are large, black and prominent. The ears are short, rounded, edged with white, and terminated by tufts of black hair. There are six short rounded incisors in each jaw, two canines, which are long and sharp, and six molars on each side. The hair on the legs is short and of a brownish tinge. The feet are five-toed, with large strong claws; the soles are bare, and applied to the ground throughout the whole of their length; the hind ones are longer than the fore.[3]

In general build the binturong is essentially like Paradoxurus and Paguma but more massive in the length of the tail, legs and feet, in the structure of the scent glands and larger size of rhinarium, which is more convex with a median groove being much narrower above the philtrum. The contour hairs of the coat are much longer and coarser, and the long hairs clothing the whole of the back of the ears project beyond the tip as a definite tuft. The anterior bursa flap of the ears is more widely and less deeply emarginate. The tail is more muscular, especially at the base, and in colour generally like the body, but commonly paler at the base beneath. The body hairs are frequently partly whitish or buff, giving a speckled appearance to the pelage, sometimes so extensively pale that the whole body is mostly straw-coloured or grey, the young being often at all events paler than the adults, but the head is always closely speckled with grey or buff. The long mystacial vibrissae are conspicuously white, and there is a white rim on the summit of the otherwise black ear. The glandular area is whitish.[4]

The binturong is sometimes compared to a bear, but it is considerably smaller, being no larger than a small dog. It is, however, the largest living species of the Viverridae, only rivaled by the African civet. Its average head-and-body length is usually between 60 and 97 cm (24 and 38 in), and weight typically ranges between 9 and 20 kg (20 and 44 lb), although some exceptional individuals have been known to weigh 23 kg (51 lb) or more.[5] The tail can act as a fifth hand and is nearly as long as the animal's own length at 50 to 84 cm (20 to 33 in). Females are 20% larger than males.[6]

Distribution and habitat

Binturongs occur from India, Nepal, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Myanmar, Thailand, Malaysia to Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam and Yunnan in China, and from Sumatra, Kalimantan and Java in Indonesia to Palawan in the Philippines.[2]

Binturongs are confined to tall forest.[7] In the Philippines, they are found in primary and secondary lowland forest, including grassland–forest mosaic from sea level to 400 m (1,300 ft).[8] In Laos, they have been observed in extensive evergreen forest.[9] In Thailand's Khao Yai National Park, several individuals were observed feeding in a fig tree and on a vine.[10] In Myanmar, binturongs were photographed on the ground in the Tanintharyi Nature Reserve at an altitude of 60 m (200 ft), in the Hukaung Valley at altitudes from 220–280 m (720–920 ft), in the Rakhine Yoma Elephant Reserve at 580 m (1,900 ft) and at three other sites up to 1,190 m (3,900 ft) elevation.[11] In Malaysia, binturongs were recorded in secondary forest surrounding a palm estate that was logged in the 1970s.[12]

Distribution of subspecies

Nine subspecies have been recognized forming two clades. The northern clade from mainland Asia has been separated from the Sundaic clade by the Isthmus of Kra.[13]

- A. b. binturong (Raffles, 1821) – ranges from Malacca to southwestern Thailand and southern Myanmar;[14]

- A. b. albifrons (Cuvier, 1822) – is distributed in the Eastern Himalayas to Bhutan, northern Myanmar and Indochina;[14]

- A. b. penicillatus (Temminck, 1835) – lives in Java;[13]

- A. b. whitei (Allen, 1910) – lives in Palawan, Philippines;[13]

- A. b. pageli (Schwarz, 1911) – lives in Borneo;[13]

- A. b. gairdneri (Thomas, 1916) – lives in northern Thailand;[13]

- A. b. niasensis (Lyon, 1916) – lives in Sumatra;[13]

- A. b. kerkhoveni (Sody, 1936) – lives in Bangka Island;[13]

- A. b. memglaensis (Wang and Li, 1987) – is distributed in Yunnan province;[13]

Ecology and behavior

Binturongs are active during the day and at night.[9][10] Thirteen camera trap photograph events involved one around dusk, seven in full night and five in broad daylight. All photographs were of single animals, and all were taken on the ground. As binturongs are not very nimble, they may have to descend to the ground relatively frequently when moving between trees.[11]

Five radio-collared binturongs in the Phiu Khieo Wildlife Sanctuary exhibited an arrhythmic activity dominated by crepuscular and nocturnal tendencies with peaks in the early morning and late evening. Reduced inactivity periods occurred from midday to late afternoon. They moved between 25 m (82 ft) and 2,698 m (8,852 ft) daily in the dry season and increased their daily movement to 4,143 m (13,593 ft) in the wet season. Ranges sizes of males varied between 0.9 km2 (0.35 sq mi) and 6.1 km2 (2.4 sq mi). Two males showed slightly larger ranges in the wet season. Their ranges overlapped between 30–70%.[15] The average home range of a radio-collared female in the Khao Yai National Park was estimated at 4 km2 (1.5 sq mi), and the one of a male at 4.5 to 20.5 km2 (1.7 to 7.9 sq mi). [16]

Pocock observed the behaviour of several captive binturongs in the London Zoological Gardens. When resting they lie curled up, with the head tucked under the tail. They never leap, but climb skilfully, albeit slowly, progressing with equal ease and confidence along the upper side of branches or, upside down, beneath them, the prehensile tail being always in readiness as a help, and they descend the vertical bars of the cage head first, gripping them between their paws and using the prehensile tail as a check. When irritated they growl fiercely, and when on the prowl may periodically utter a series of low grunts or a hissing sound made by expelling the air through partially opened lips.[4]

The binturong also uses its tail to communicate, through the scent glands on either side of the anus in both males and females. The females also possess paired scent glands on either side of the vulva.[17] The scent of binturong musk is often compared to that of warm buttered popcorn[18] and cornbread. The binturong brushes its tail against trees and howls to announce its presence to other binturongs.

Although they are sympatric with several potential predators, including leopards, clouded leopards and reticulated pythons, predation on adults is reportedly quite rare. This is believed to be due in part to its arboreal, nocturnal habits. Also, although normally quite shy, it can be notoriously aggressive when harassed. It is reported to initially urinate or defecate on a threat and then, if teeth-baring and snarling does not additionally deter the threat, will use its powerful jaws and teeth in self-defense.[19]

No studies of the dietary preferences in the wild have been conducted. However, the primary food for wild binturongs is believed to be fruit. Since the species is often spotted in fig trees, it is often thought that figs rank among the favored elements in the species' diet. Other foods known to be consumed have included eggs, shoots, leaves, arthropods and small vertebrates, such as rodents or birds.[5] Cases where binturongs have come to riversides and caught fish have also been reported.[20] The binturong is an important animal for dispersal of seeds, especially those of the strangler fig, because of its ability to scarify the seed's tough outer covering.[21]

Reproduction

The estrous period of the binturong is 81 days, with a gestation of 91 days. The average age of sexual maturation is 30.4 months for females and 27.7 months for males. Fertility lasts until 15 years of age.[22] The binturong is one of approximately 100 species of mammal believed by many husbandry experts to be capable of embryonic diapause, or delayed implantation, which allows the female of the species to time parturition to coincide with favorable environmental conditions. Typical birthing is of two offspring, but up to six may occur.

The maximum known lifespan in captivity is thought to be over 25 years of age.[20]

Threats

The primary threat to the binturong is destruction of forest habitats. Although the binturong continues to occur over a large range, the populations of this species has been greatly reduced. Mostly, this is due directly to human activities. Throughout South Asia, clear-cutting of native forest is rampant. Although many areas now have treed plantations, there is no evidence that the binturong uses the plantations that are largely replacing natural forest in this region, major declines can be inferred based on decline in area of area of occupancy and habitat quality. Logging is especially epidemic as a problem for the binturong in the species range in China, where it is now considered Critically Endangered and in its range in Southeast Asia. The other primary threat to the species is direct gathering of specimens (often illegally) for the wildlife trade and hunting. Binturongs are often shot for their fur, meat and scent glands, as is common for all varieties of medium to large-sized wild mammals in its range. It is also now a fairly popular captive species.[2]

In captivity, the binturong has been noted for its reported intelligence as well as its curious disposition and catholic diet. However, its occasional ill-temperament makes it a difficult pet at best and better handled by experienced wildlife handlers and zookeepers.[19] The Orang Asli of Malaysia keep binturong as pets.

References

- ^ Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 549. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b c d Template:IUCN

- ^ a b Raffles, T. S. (1822). XVII. Descriptive Catalogue of a Zoological Collection, made on account of the Honourable East India Company, in the Island of Sumatra and its Vicinity, under the Direction of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, Lieutenant-Governor of Fort Marlborough', with additional Notices illustrative of the Natural History of those Countries. The Transactions of the Linnean Society of London, Volume XIII: 239–274.

- ^ a b c Pocock, R. I. (1939). The fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma. Mammalia. – Volume 1. Taylor and Francis, London. Pp. 431–439.

- ^ a b Hunter, L. (2011) Carnivores of the World. Princeton University Press, ISBN 9780691152288

- ^ San Diego Zoo. "Mammal: Binturong". Sandiegozoo.org. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ^ Lekalul, B. and McNeely, J. A. (1977). Mammals of Thailand. Association for the Conservation of Wildlife, Bangkok.

- ^ Rabor, D. S. (1986). Guide to the Philippine flora and fauna. Natural Resources Management Centre. Ministry of Natural Resources and University of the Philippines.

- ^ a b Duckworth, J. W. (1997). Small carnivores in Laos: a status review with notes on ecology, behaviour and conservation. Small Carnivore Conservation 16: 1–21.

- ^ a b Nettlebeck, A. R. (1997). Sightings of Binturongs Arctictis binturong in the Khao Yai National Park, Thailand. Small Carnivore Conservation 16: 21–24.

- ^ a b Than Zaw, Saw Htun, Saw Htoo Tta Po, Myint Maung, Lynam, A. J., Kyaw Thinn Latt and Duckworth, J. W. (2008). Status and distribution of small carnivores in Myanmar. Small Carnivore Conservation 38: 2–28.

- ^ Azlan, J. M. (2003). The diversity and conservation of mustelids, viverrids, and herpestids in a disturbed forest in Peninsular Malaysia. Small Carnivore Conservation 29: 8–9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cosson, L., Grassman, L. L., Zubaid, A., Vellayan, S., Tillier, A., and Veron, G. (2007). Genetic diversity of captive binturongs (Arctictis binturong, Viverridae, Carnivora): implications for conservation. Journal of Zoology, 271(4): 386–395.

- ^ a b Ellerman, J. R., Morrison-Scott, T. C. S. (1966). Checklist of Palaearctic and Indian mammals 1758 to 1946. Second edition. British Museum of Natural History, London. Page 290

- ^ Grassman, L. I., Jr. (2005). "Ranging, habitat use and activity patterns of binturong Arctictis binturong and yellow-throated marten Martes flavigula in north-central Thailand" (PDF). Wildlife Biology. 11 (1): 49–57. doi:10.2981/0909-6396(2005)11[49:RHUAAP]2.0.CO;2.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Austin, S. C. (2002). Ecology of sympatric carnivores in the Khao Yai National Park, Thailand. PhD thesis, Texas University.

- ^ Story, H. E. (1945). "The External Genitalia and Perfume Gland in Arctictis binturong". Journal of Mammalogy. 26 (1): 64–66. doi:10.2307/1375032.

- ^ "Mammals: Binturong". Zoological Society of San Diego. Retrieved 2007-10-17.

- ^ a b Madya Dr. Ahmad Hj. Ismail Binturong. ukm.my

- ^ a b Macdonald, D.W. (2009). The Encyclopedia of Mammals. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- ^ "Meet the animals- Binturong". Carnivore Preservation Trust. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ^ Wemmer, C. (1981). "Copulatory Behavior and Reproduction in the Binturong, Arctictis binturong". Journal of Mammalogy. 62 (2): 342–352. doi:10.2307/1380710. JSTOR 1380710.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

External links

- IUCN Red List vulnerable species

- Viverrids

- Mammals of India

- Mammals of Bhutan

- Mammals of Bangladesh

- Mammals of Indonesia

- Mammals of Thailand

- Mammals of the Philippines

- Monotypic mammal genera

- Animals described in 1821

- Carnivora of Malaysia

- Mammals of Borneo

- Mammals of China

- Mammals of Vietnam

- Mammals of Laos

- Mammals of Cambodia

- Mammals of Burma

- Mammals of Brunei