Gharial: Difference between revisions

→Taxonomy: The evidence for gharials and crocodiles as sister groups is overwhelming |

BhagyaMani (talk | contribs) →Taxonomy: edited refs |

||

| Line 118: | Line 118: | ||

* Alternatively, the three groups are all classed together as the family Crocodylidae, but belong to the [[family (biology)|subfamilies]] Gavialinae, Crocodylinae, and [[Alligatorinae]]. |

* Alternatively, the three groups are all classed together as the family Crocodylidae, but belong to the [[family (biology)|subfamilies]] Gavialinae, Crocodylinae, and [[Alligatorinae]]. |

||

According to [[Molecular genetics|molecular genetic]] studies the gharial and the [[false gharial]] (''Tomistoma'') are close relatives, which would support to place them in the same family.<ref>{{cite journal|pmid=16211427|year=2005|last1=Janke|first1=A|last2=Gullberg|first2=A|last3=Hughes|first3=S|last4=Aggarwal|first4= |

According to [[Molecular genetics|molecular genetic]] studies the gharial and the [[false gharial]] (''Tomistoma'') are close relatives, which would support to place them in the same family.<ref>{{cite journal |pmid=16211427 |year=2005 |last1=Janke|first1=A. |last2=Gullberg|first2=A. |last3=Hughes|first3=S. |last4=Aggarwal|first4=R. K. |last5=Arnason|first5=U. |title=Mitogenomic analyses place the gharial (''Gavialis gangeticus'') on the crocodile tree and provide pre-K/T divergence times for most crocodilians |volume=61 |issue=5|pages=620–626|doi=10.1007/s00239-004-0336-9|journal=Journal of Molecular Evolution}}</ref> Furthermore, molecular studies consistently and unambiguously show the Gavialidae to be a [[sister group]] of the [[Crocodylidae]] to the exclusion of [[Alligatoridae]], rendering [[Brevirostres]] [[paraphyletic]] and [[Gavialoidea]] perhaps [[polyphyletic]]. The [[clade]] including crocodiles and gharials has been suggested to be called '''Longirostres'''.<ref>Harshman, J., Huddleston, C. J., Bollback, J. P., Parsons, T. J., Braun, M. J. (2003). ''True and false gharials: a nuclear gene phylogeny of Crocodylia''. Systematic Biology 52: 386–402.</ref><ref>Brochu, C. A. (2003). [http://myweb.astate.edu/strauth/Herpetology/Phylogenetic%20Approaches%20to%20Croc.%20History.annurev.earth.31.100901.pdf ''Phylogenetic Approaches to Crocodylian History'']. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 31: 357–397.</ref><ref>Gatesy, J. and Amato, G. (2008). ''The rapid accumulation of consistent molecular support for intergeneric crocodylian relationships''. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 48:1232–1237.</ref> |

||

===Palaeontological classification=== |

===Palaeontological classification=== |

||

Revision as of 08:51, 26 February 2013

| Gharial | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | G. gangeticus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Gavialis gangeticus (Gmelin, 1789)

| |

| |

The gharial (Gavialis gangeticus) is a crocodilian of the family Gavialidae that is native to the Indian subcontinent and also called gavial and fish-eating crocodile. As the species has undergone both chronic long term and a rapid short-term declines it is listed as a Critically Endangered by IUCN.[1]

The gharial is one of three crocodilians native to India, apart from the mugger crocodile and the saltwater crocodile.[2] It is one of the longest of all living crocodilians.[3]

The Nepali and Hindi word घड़ा ghaṛā means earthenware pot, pitcher, water vessel.[4][5]

Characteristics

The gharial is characterised by its extremely long, thin jaws, regarded as an adaptation to a predominantly fish diet. Males reach up to 6 m (20 ft) with an average weight of around 160 kg (350 lb).[6]

It is dark or light olive above with dark cross-bands and speckling on the head, body, and tail. Dorsal surfaces become dark, almost gray-black, at about 20 years of age. Ventrals are yellowish-white. The neck is elongated and thick. The dorsals are more or less restricted to the median regions of the back. The fingers are extremely short and thickly emarginated with a web. Males develop a hollow nasal protuberance at sexual maturity.[7] This bulbous growth on the tip of their snout called ghara is used to modify and amplify “hisses” snorted through the underlying nostrils. The resultant sound can be heard for nearly a kilometer on a still day. The ghara renders gharials the only extant crocodilian with visible sexual dimorphism.[8] Although the function of the ghara is not well understood, it is apparently used as a visual sex indicator, as a sound resonator, or for bubbling or other associated sexual behaviours.[9]

The average size of mature gharials is 3.5 to 4.5 m (11 to 15 ft). The maximum recorded size is 6.25 m (20.5 ft). Hatchlings approximate 37 cm (15 in).[10] Young gharials can reach a length of 1 m (3.3 ft) in eighteen months.[3]

The average body weight ranges from 159 to 250 kg (351 to 551 lb). Males commonly attain a total length of 3 to 5 m (9.8 to 16.4 ft), while females are smaller and reach a body length of up to 2.7 to 3.75 m (8.9 to 12.3 ft).[11]

The elongated, narrow snout is lined by 110 sharp interdigitated teeth, and becomes proportionally shorter and thicker as an animal ages. The well-developed laterally flattened tail and webbed rear feet provide tremendous manoeuvrability in deepwater habitat. On land, however, an adult gharial can only push itself forward and slide on its belly. The laterally compressed tail serves both to propel the animal and as a base from which to strike at prey.[8] There are 27 to 29 upper and 25 or 26 lower teeth on each side. These teeth are not received into interdental pits; the first, second, and third mandibular teeth fit into notches in the upper jaw. The front teeth are the largest. The snout is narrow and long, with a dilation at the end and its nasal bones are comparatively short and are widely separated from the pre-maxillaries. The nasal opening of a gharial is smaller than the supra-temporal fossae. The lower anterior margin of orbit (jugal) is raised and its mandibular symphysis is extremely long, extending to the 23rd or 24th tooth. A dorsal shield is formed from four longitudinal series of juxtaposed, keeled, and bony scutes. The length of the snout is 3.5 (in adults) to 5.5 times (in young) the breadth of the snout's base. Nuchal and dorsal scutes form a single continuous shield composed of 21 or 22 transverse series. Gharials have an outer row of soft, smooth, or feebly keeled scutes in addition to the bony dorsal scutes. They also have two small post-occipital scutes. The outer toes are two-thirds webbed, while the middle toe is only one-third webbed. They have a strong crest on the outer edge of the forearm, leg, and foot. Typically, adult gharials have a dark olive colour tone while young ones are pale olive, with dark brown spots or cross-bands.[12]

The three largest examples reported were a 6.5 m (21 ft) gharial killed in the Gogra River of Faizabad in August 1920; a 6.3 m (21 ft) individual shot in the Cheko River of Jalpaiguri in 1934; and a giant of 7 m (23 ft), which was shot in the Kosi River of northern Bihar in January 1924. Though specimens of over 6 m (20 ft) were not uncommon in the past, such large individuals are not known to exist today.[13]

Further enhancing its swimming abilities, the body of the gharial is relatively cylindrical in shape, compared with the broader, more powerfully built body of a saltwater or Nile crocodile built for capturing various prey from the edges of waterways.[citation needed]

Distribution and habitat

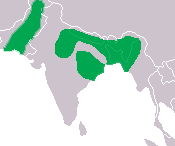

Gharials once thrived in all the major river systems of the Indian subcontinent, spanning the rivers of its northern part from the Indus River in Pakistan across the Gangetic floodplain to the Irrawaddy River in Myanmar. Today, they are extinct in the Indus River, in the Brahmaputra of Bhutan and Bangladesh and in the Irrawaddy River. Their distribution is now limited to only 2% of their former range:[8]

- In India, small populations are present and increasing in the rivers of the National Chambal Sanctuary, Katarniaghat Wildlife Sanctuary, Son River Sanctuary and the rainforest biome of Mahanadi in Satkosia Gorge Sanctuary, Odisha, where they apparently do not breed;[14]

- In Nepal, small populations are present and slowly recovering in tributaries of the Ganges, such as the Narayani-Rapti river system in Chitwan National Park and the Karnali-Babai river system in Bardia National Park.[10][15]

They are sympatric with the mugger crocodile (Crocodylus palustris) and formerly used to be with the saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) in the delta of Irrawaddy River.[16]

In 1977, four nests were recorded in the Girwa River of Katarniaghat Wildlife Sanctuary, where 909 gharials were released until 2006. Twenty nests were recorded in 2006, so 16 nesting females resulted from 30 years of reintroductions, which is equivalent to 2% of the total pre-2006 releases. This is seemingly not a great achievement for the money and effort spent, and as several knowledgeable researchers have suggested, perhaps carrying capacity has been reached there. In 1978, twelve nests were recorded in the Chambal River in the National Chambal Sanctuary, where 3,776 gharials were released until 2006. By 2006, nesting had increased by over 500% to 68 nests, but the recruited mature, reproducing females constituted only about 2% of the total number released. The newly hatched young are especially prone to being flushed downstream out of the protected areas during the annual monsoonal flooding.[1]

Ecology and behavior

Gharials are arguably the most thoroughly aquatic of the extant crocodilians, and adults apparently do not have the ability to walk in a semi-upright stance as other crocodilians do. They are typically residents of flowing rivers with deep pools that have high sand banks and good fish stocks. Exposed sand banks are used for nesting.[3]

Diet

The elongated, narrow snout reduces resistance to water when snagging fish, and the very sharp interdigitated teeth are well adapted for capturing fish.[8] Young gharials eat insects, tadpoles, small fish and frogs. Adults feed on fish and small crustaceans. Their jaws are too thin and delicate to grab larger prey. They catch fish by lying in wait for fish to swim by, and then catch the fish by quickly whipping their head sideways and grabbing it in their jaws. They herd fish with their body against the shore, and stun fish using their underwater jaw clap. They do not chew their prey but swallow it whole.[11]

Gharials do not kill and eat humans.[11] Jewellery found in their stomachs may have been the reason for the myth that gharials are man-eaters. They may have swallowed this jewellery as gastroliths used to aid digestion or buoyancy management.[citation needed]

Reproduction

Males mature at around 13 years old, which is when the ghara begins to grow on the snout. They advertise for mates by making hissing and buzzing noises as they patrol their territory, and may have a harem of females within a territory that they aggressively defend from other males. Females communicate their readiness to mate by raising their snout upwards. During courtship, males and females will follow prospective mates around until a suitable mate is decided upon. Courtship also involves head and snout rubbing and mounting by both males and females.[11]

Mating usually occurs during December and January.[8] In India, gharials nest in March and April, the dry season; the female lays 20–95 eggs in a hole 50–60 cm (20–24 in) deep, dug with the hind feet in a riverside sand or silt bank, 1–5 m (3.3–16.4 ft) from the waterline.[3] The eggs are the largest of any crocodilian species, weighing an average of 160 g.[8] After 71 to 93 days of incubation, young gharials hatch in July just before the monsoon. Temperature is likely an important influence on determining gender.[3] Female gharials dig up the young in response to hatching chirps, but do not assist the hatchlings to the water. They will however guard the hatchlings for some time.[8]

Threats

According to IUCN, there has been a population decline of 96–98% over a three-generation period since 1946, and the once widespread population of an estimated 5,000 to 10,000 individuals has been reduced to a very small number of widely spaced subpopulations of fewer than 235 individuals in 2006. The drastic decline in the gharial population can be attributed to a variety of causes including over-hunting for skins and trophies, egg collection for consumption, killing for indigenous medicine, and killing by fishermen. Hunting is no longer considered to be a significant threat. However, the wild population of gharials has undergone a drastic decline of about 58% within nine years between 1997 and 2006 due to:[1]

- the increasing intensity of fishing and the use of gill nets, which is rapidly killing many of the scarce adults and many subadults — a threat prevalent throughout most of the present gharial habitat, even in protected areas;

- the excessive, irreversible loss of riverine habitat caused by the construction of dams, barrages, irrigation canals, siltation, changes in river course, artificial embankments, sand-mining, riparian agriculture, and domestic and feral livestock, which have combined to cause an extreme limitation to gharial range.

In December 2007, several gharial were found dead in the Chambal River. Initially, fishermen were suspected to have illegally caught fish using nets that cause entangled gharial to drown. Subsequent post-mortems and pathological testing of tissue samples from dead gharials revealed high levels of heavy metals such as lead and cadmium, which together with stomach ulcers and protozoan parasites reported in most necropsies were incriminated as the cause of death.[17]

Conservation

Gavialis gangeticus is listed on CITES Appendix I.[1]

By 1976, the estimated total population of wild gharials in the world had declined from what is thought to have been 5,000 to 10,000 in the 1940s to less than 200, a decline of about 96%. The Indian government subsequently accorded protection under the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972.[8]

In 1997, the total population was estimated at 436 adult gharials that had declined to 182 in 2006. This drastic decline has happened within a period of nine years, well within the span of one generation, and qualifies the gharial for Critically Endangered listing by the IUCN.[1] Estimates from population surveys carried out in 2007 indicated 200-300 breeding adults left in the world.[18]

In situ initiatives

Conservation programs have been undertaken in India and Nepal, based on the establishment of protected areas and restocking these with animals born in captivity, but nowhere has restocking re-established viable populations. Juvenile gharials were released into largely inhospitable habitats in Indian and Nepali rivers and left to their fate. Reintroduction didn't work so well, largely due to growing and uncontrolled anthropogenic pressures, including depletion of fish resources. Monitoring has not been consistently carried out, and little research on adaptation, migration and other key aspects has been conducted.[1]

Project Crocodile began in 1975 under the auspices of the Government of India with the aid of the United Nations Development Fund and Food and Agriculture Organization. The project included an intensive captive breeding and rearing program intended to restock habitats with low numbers of gharials. An acute shortage of gharial eggs was overcome by their purchase from Nepal. A male gharial was flown in from the Frankfurt Zoo to become one of the founding animals of the breeding program. Sixteen crocodile rehabilitation centers and five crocodile sanctuaries including the National Chambal Sanctuary and Katerniaghat Wildlife Sanctuary were established in India between 1975 and 1982. By 2004, 12,000 gharial eggs had been collected from wild and captive-breeding nests, and over 5,000 gharials reared to about a meter or more in length and released into the wild. But in 1991, funds were withdrawn for the captive breeding and egg-collection programs. In 1997–1998, over 1,200 gharials and over 75 nests were located in the National Chambal Sanctuary. But no surveys were carried out between 1999 and 2003.[8]

In December 2010, the then Indian Minister for Environment and Forests, Jairam Ramesh visited the Madras Crocodile Bank with Romulus Whitaker, and announced the formation of a National Tri-State Chambal Sanctuary Management and Coordination Committee for gharial conservation on 1,600 km2 (620 sq mi) of the National Chambal Sanctuary along the Chambal River in Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh. The Committee will comprise representatives of three states' Water Resources Ministries, states' Departments of Irrigation and Power, Wildlife Institute of India, Madras Crocodile Bank Trust, the Gharial Conservation Alliance, Development Alternatives, Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment, Worldwide Fund for Nature and the Divisional Forest officers of the three states. The Committee will plan strategies for protection of gharials and their habitat, involving further research on gharial ecology and socio-economic evaluation of dependent riparian communities. Funding for this new initiative will be mobilized as a sub-scheme of the ‘Integrated Development of Wildlife Habitats’ in the yearly amount of 50–80 million Indian Rupees (USD 1 million to 1.7 million) for five years.[19][20]

In captivity

Gharials are bred in captivity in the National Chambal Sanctuary in Uttar Pradesh, and in the Gharial Breeding Centre in Nepal's Chitwan National Park, where they are generally grown for two to three years and average about one meter, when released.[1]

In India, they are also kept in the Madras Crocodile Bank Trust, Indira Gandhi Zoological Park, Jawaharlal Nehru Biological Park in Bokaro Steel City, Bannerghatta Zoo in Bangalore, Junagadh Zoo and Biological Park Itanagar. The National Zoological Gardens of Sri Lanka and the Singapore Zoo each keep a breeding pair. The Japanese Nogeyama Zoo keeps two females. In Europe, they are kept in the Prague Zoo and the Leipzig Zoo. In the USA they are kept in the Honolulu Zoo, the Cleveland Metroparks Zoo, the Fort Worth Zoo, the San Diego Zoo, the National Zoological Park, the San Antonio Zoo and Aquarium, the St. Augustine Alligator Farm, and in Orlando's Gatorland.[21]

The French crocodile farm La Ferme aux Crocodiles received six juveniles in May 2000 from the Gharial Breeding Centre in Nepal.[22]

Ancestry

The fossil history of the Gavialoidea is quite well known, with the earliest examples diverging from the other crocodilians in the late Cretaceous. The most distinctive feature of the group is the very long, narrow snout, which is an adaptation to a diet of small fish. Although gharials have sacrificed the great mechanical strength of the robust skull and jaw that most crocodiles and alligators have, and in consequence cannot prey on large creatures, the reduced weight and water resistance of their lighter skull and very narrow jaw gives gharials the ability to catch rapidly moving fish, using a side-to-side snapping motion.

The earliest gharial may have been related to the modern types: some died out at the same time as the dinosaurs (at the end of the Cretaceous), others survived until the early Eocene. The modern forms appeared at much the same time, evolving in the estuaries and coastal waters of Africa, but crossing the Atlantic to reach South America as well. The discovery of the fossil remains of the Puerto Rican Gharial (Aktiogavialis puertorisensis) in a cave located in San Sebastián, Puerto Rico, suggested that the Caribbean served as the link between both continents.[23][24] At their peak, the Gavialoidea were numerous and diverse; they occupied much of Asia and America up until the Pliocene. One species, Rhamphosuchus crassidens of India, is believed to have grown to an enormous 15 metres (~50 feet) or more.

Taxonomy

The gharial and its extinct relatives are grouped together by taxonomists in several different ways:

- Palaentologists tend to speak of the broad lineage of gharial-like creatures over time using the term Gavialoidea.

- If the three surviving groups of crocodilians are regarded as separate families, then the gharial becomes one of two members of the Gavialidae, which is related to the families Crocodylidae (crocodiles) and Alligatoridae (alligators and caimans).

- Alternatively, the three groups are all classed together as the family Crocodylidae, but belong to the subfamilies Gavialinae, Crocodylinae, and Alligatorinae.

According to molecular genetic studies the gharial and the false gharial (Tomistoma) are close relatives, which would support to place them in the same family.[25] Furthermore, molecular studies consistently and unambiguously show the Gavialidae to be a sister group of the Crocodylidae to the exclusion of Alligatoridae, rendering Brevirostres paraphyletic and Gavialoidea perhaps polyphyletic. The clade including crocodiles and gharials has been suggested to be called Longirostres.[26][27][28]

Palaeontological classification

- Order Crocodilia

- Superfamily Gavialoidea

- Genus †Eothoracosaurus

- Genus †Thoracosaurus

- Genus †Eosuchus

- Genus †Argochampsa

- Family Gavialidae

- Subfamily Gavialinae

- Genus Gavialis

- Gavialis gangeticus – modern gharial

- †Gavialis curvirostris

- †Gavialis breviceps

- †Gavialis browni

- †Gavialis bengawanicus

- †Gavialis lewisi

- Genus Gavialis

- ?Subfamily Tomistominae

- Genus Tomistoma

- Tomistoma schlegelii, false gharial or Malayan gharial

- †Tomistoma lusitanica

- †Tomistoma cairense

- Genus †Eogavialis

- Genus †Kentisuchus

- Genus †Gavialosuchus

- Genus †Paratomistoma

- Genus †Thecachampsa

- Genus †Rhamphosuchus

- Genus †Toyotamaphimeia

- Genus Tomistoma

- Subfamily †Gryposuchinae

- Genus †Aktiogavialis

- Genus †Gryposuchus

- Genus †Ikanogavialis

- Genus †Siquisiquesuchus

- Genus †Piscogavialis

- Genus †Hesperogavialis

- Subfamily Gavialinae

- Superfamily Gavialoidea

Vernacular names

Common names include Indian gharial, Indian gavial, Fish-eating crocodile, Gavial del Ganges, Gavial du Gange, Long-nosed crocodile, Bahsoolia, Chimpta, Lamthora, Mecho Kumhir, Naka, Nakar, Shormon, Thantia, Thondre, Garial.

Appearances in popular culture

- In the PlayStation 2 video game, Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater, one of the more noted animals that Naked Snake can consume for his survival is the Indian Gavial.

- The Ravnica: City of Guilds expansion of the Magic: The Gathering trading card game features a "Crocodile" creature called Grayscaled Gharial,[29] and the Shards of Alara expansion includes the creature Algae Gharial.[30]

- In Esperanto, the verb gaviali ("to gharial") means to speak Esperanto in a situation where another language would be more appropriate.

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Template:IUCN

- ^ Choudhury, B.C. (ed.) (2006). West Asia Regional Report. Crocodile Specialist Group Steering Committee Meeting, 19 June 2006.

- ^ a b c d e Whitaker, R. and D. Basu (1983). "The Gharial (Gavialis gangeticus): A review". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 79: 531–548.

- ^ Turner, R. L. (1931). "A Comparative and Etymological Dictionary of the Nepali Language".

- ^ Bahri, H. (1989). Learners' Hindi-English dictionary. Siksarthi Hindi-Angrejhi sabdakosa. Rajapala, Delhi.

- ^ Stevenson, C. and Whitaker, R. (2010). Gharial Gavialis gangeticus pp. 139–143 in: Manolis, S. C. and C. Stevenson. (eds.) Crocodiles. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. Third Edition. Crocodile Specialist Group, Darwin.

- ^ Brazaitis, P. (2001). A Guide to the Identification of the Living Species of Crocodilians. Science Resource Center, Wildlife Conservation Society

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Whitaker, R., Members of the Gharial Multi-Task Force, Madras Crocodile Bank (2007). "The Gharial: Going Extinct Again" (PDF). Iguana. 14 (1): 24–33.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Martin, B. G. H. and Bellairs, A. D’A. (1977). "The narial excresence and pterygoid bulla of the gharial, Gavialis gangeticus (Crocodilia)". Journal of Zoology. 182 (4): 541–558. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1977.tb04169.x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Maskey, T. M., Percival, H.F. (1994) Status and Conservation of Gharial in Nepal. Presented at the 12th Working Meeting of the Crocodile Specialist Group, Thailand.

- ^ a b c d GCA (2009). Gharial biology. Gharial Conservation Alliance

- ^ Boulenger, G. A. (1890). The Fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma. Reptilia and Batrachia. London: Taylor and Francis.

- ^ Wood, G. L. (ed.) (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. Sterling Pub Co Inc. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9

- ^ Bustard, H.R. (1983). "Movement of wild Gharial, Gavialis gangeticus (Gmelin) in the River Mahanadi, Orissa (India)". British Journal of Herpetology. 6: 287–291.

- ^ Priol, P. (2003) Gharial field study report. A report submitted to Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation, Kathmandu, Nepal.

- ^ Rao, R.J., Choudhury, B.C. (1990). "Sympatric distribution of Gharial Gavialis gangeticus and Mugger Crocodylus palustris in India". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 89: 313–314.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Whitaker, R., Basu, D. and Huchzermeyer, F. (2008). Update on gharial mass mortality in National Chambal Sanctuary. Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter 27 (1): 4–8.

- ^ GCA (2008). Mass Gharial Deaths in Chambal. Gharial Conservation Alliance

- ^ "Gharial Conservation gets a leg-up!". The Madras Crocodile Bank Trust and Center for Herpetology. 30 December 2010.

- ^ Oppilli, P. (27 December 2010). "A sanctuary coming up for ghariyals". The Hindu. Retrieved 2010-12-27.

- ^ International Species Information System (23 December 2011). ISIS Species Holdings: Gavialis gangeticus. Accessed 24 January 2012

- ^ Fougeirol, L. (2009). "Le gavial du Gange, un rêve. www.luc-fougeirol.com

- ^ "Crocodiles Swam Atlantic?". ABC: KCRG-TV9. 2007-03-23. Retrieved 2012-07-02.

{{cite web}}: no-break space character in|publisher=at position 5 (help); no-break space character in|title=at position 11 (help) - ^ Vélez-Juarbe, Jorge (2007-03-06). "A gharial from the Oligocene of Puerto Rico: transoceanic dispersal in the history of a non-marine reptile". Proceedings of the Royal Society. 274 (1615). The Royal Society: 1245–54. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.0455. PMC 2176176. PMID 17341454.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Janke, A.; Gullberg, A.; Hughes, S.; Aggarwal, R. K.; Arnason, U. (2005). "Mitogenomic analyses place the gharial (Gavialis gangeticus) on the crocodile tree and provide pre-K/T divergence times for most crocodilians". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 61 (5): 620–626. doi:10.1007/s00239-004-0336-9. PMID 16211427.

- ^ Harshman, J., Huddleston, C. J., Bollback, J. P., Parsons, T. J., Braun, M. J. (2003). True and false gharials: a nuclear gene phylogeny of Crocodylia. Systematic Biology 52: 386–402.

- ^ Brochu, C. A. (2003). Phylogenetic Approaches to Crocodylian History. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 31: 357–397.

- ^ Gatesy, J. and Amato, G. (2008). The rapid accumulation of consistent molecular support for intergeneric crocodylian relationships. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 48:1232–1237.

- ^ Grayscaled Gharial image. hraj.cz. Retrieved on 2012-06-19.

- ^ "Algae Gharial (Shards of Alara) – Gatherer – Magic: The Gathering". Gatherer.wizards.com. Retrieved 2010-03-16.