History of Halifax, Nova Scotia: Difference between revisions

Hantsheroes (talk | contribs) |

Hantsheroes (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 82: | Line 82: | ||

=== Capture of the USS Chesapeake === |

=== Capture of the USS Chesapeake === |

||

[[File:John Christian Schetky, H.M.S. Shannon Leading Her Prize the American Frigate Chesapeake into Halifax Harbour (c. 1830).jpg|left|thumb|200px|HMS ''Shannon'' leads [[Capture of USS Chesapeake|the captured USS ''Chesapeake'']] into Halifax]] |

[[File:John Christian Schetky, H.M.S. Shannon Leading Her Prize the American Frigate Chesapeake into Halifax Harbour (c. 1830).jpg|left|thumb|200px|HMS ''Shannon'' leads [[Capture of USS Chesapeake|the captured USS ''Chesapeake'']] into Halifax]] |

||

Several notable naval engagements occurred off the Halifax station. Most dramatic was the victory of the Halifax-based British frigate [[HMS Shannon (1806)|HMS ''Shannon'']] which captured the American frigate [[USS Chesapeake (1799)|USS ''Chesapeake'']] and brought her to Halifax as prize. The 320 American survivors of the [[Capture of USS Chesapeake|Battle of Boston Harbor]] were interned on [[Melville Island (Nova Scotia)]] in 1813, and their ship, renamed the [[USS Chesapeake (1799)|HMS ''Chesapeake'']], was used to ferry prisoners from Melville to England's [[Dartmoor (HM Prison)|Dartmoor Prison]].{{sfn|Shea|Watts|2005|pp=27–29}} Many officers were paroled to Halifax, but some began a riot at a performance of a patriotic song about the ''Chesapeake'''s defeat.{{sfn|Shea|Watts|2005|p=30}} Parole restrictions were tightened: beginning in 1814, paroled officers were required to attend a monthly muster on Melville Island, and those who violated their parole were confined to the prison.{{sfn|Shea|Watts|2005|p=31}} |

Several notable naval engagements occurred off the Halifax station. Most dramatic was the victory of the Halifax-based British frigate [[HMS Shannon (1806)|HMS ''Shannon'']] which captured the American frigate [[USS Chesapeake (1799)|USS ''Chesapeake'']] and brought her to Halifax as prize. The ''Shannon'', commanded by Halifax's own [[Provo Wallis]], escorted her prize into Halifax, arriving there on 6 June. On the entry of the two frigates into the harbour, the naval ships already at anchor manned their yards, bands played martial music and each ship ''Shannon'' passed greeted her with cheers.<ref>Padfield 1968, p. 188</ref> The 320 American survivors of the [[Capture of USS Chesapeake|Battle of Boston Harbor]] were interned on [[Melville Island (Nova Scotia)]] in 1813, and their ship, renamed the [[USS Chesapeake (1799)|HMS ''Chesapeake'']], was used to ferry prisoners from Melville to England's [[Dartmoor (HM Prison)|Dartmoor Prison]].{{sfn|Shea|Watts|2005|pp=27–29}} Many officers were paroled to Halifax, but some began a riot at a performance of a patriotic song about the ''Chesapeake'''s defeat.{{sfn|Shea|Watts|2005|p=30}} Parole restrictions were tightened: beginning in 1814, paroled officers were required to attend a monthly muster on Melville Island, and those who violated their parole were confined to the prison.{{sfn|Shea|Watts|2005|p=31}} |

||

As well, an invasion force which attacked Washington in 1813, and burned the Capitol and White House was sent from Halifax. The leader of the force was [[Robert Ross (British Army officer)|Robert Ross]], who died in the battle and was buried in Halifax. |

As well, an invasion force which attacked Washington in 1813, and burned the Capitol and White House was sent from Halifax. The leader of the force was [[Robert Ross (British Army officer)|Robert Ross]], who died in the battle and was buried in Halifax. |

||

Revision as of 10:19, 31 January 2013

| History of Halifax, Nova Scotia |

|---|

|

The Halifax Regional Municipality (HRM) was first settled by Acadians and Mi'kmaq people. The British settled peninsula Halifax (1749), which sparked Father Le Loutre's War. To guard against Mi'kmaq, Acadian, and French attacks on the new Protestant settlements, British fortifications were erected in Halifax (Citadel Hill)(1749), Bedford (Fort Sackville) (1749), Dartmouth (1750), and Lawrencetown (1754). St. Margaret's Bay first got settled by French-speaking Foreign Protestants at French Village, Nova Scotia who migrated from Lunenburg, Nova Scotia during the American Revolution. All of these regions were amalgamated into the HRM in 1996. While all of the regions of HRM developed separately over the last 250 years, their histories have also been intertwined.

18th Century

The HRM was settled for thousands of years by the Mi'kmaq. Those who settled on Halifax Harbour called it Jipugtug (anglicised as "Chebucto"), meaning Great Harbour. Prior to the establishment of Halifax, the most remarkable event in the region was the tragic fate of the Duc d'Anville Expedition, which led to significant disease and death among the local Mi'kmaq people. The first European settlement in the HRM was an Acadian community at present-day Lawrencetown. These Acadians joined the Acadian Exodus when the British established themselves on Halifax Peninsula. The establishment of the Town of Halifax, named after the British Earl of Halifax, in 1749 led to the colonial capital being transferred from Annapolis Royal.

Father Le Loutre's War

The establishment of Halifax marked the beginning of Father Le Loutre's War. The war began when Edward Cornwallis arrived to establish Halifax with 13 transports and a sloop of war on June 21, 1749.[1] By unilaterally establishing Halifax the British were violating earlier treaties with the Mi'kmaq (1726), which were signed after Father Rale's War.[2] Cornwallis brought along 1,176 settlers and their families. In 1750, the sailing ship Alderney arrived with 151 immigrants. Municipal officials at Halifax decided that these new arrivals should be settled on the eastern side of Halifax Harbour.

During Father Le Loutre's War, the Mi'kmaq and Acadians raided in the capital region (Halifax and Dartmouth) 12 times. On September 30, 1749, about forty Mi'kmaq attacked six men who were in Dartmouth cutting trees. Four of them were killed on the spot, one was taken prisoner and one escaped.[3] Two of the men were scalped and the heads of the others were cut off. The attack was on the saw mill which was under the command of Major Gilman. Six of his men had been sent to cut wood. Four were killed and one was carried off. The other escaped and gave the alarm. A detachment of rangers was sent after the raiding party and cut off the heads of two Mi'kmaq and scapled one.[4] This raid was the first of eight against Dartmouth.

The result of the raid, on October 2, 1749, Cornwallis offered a bounty on the head of every Mi'kmaq. He set the amount at the same rate that the Mi'kmaq received from the French for British scalps. As well, to carry out this task, two companies of rangers raised, one led by Captain Francis Bartelo and the other by Captain William Clapham. These two companies served along side that of John Gorham's company. The three companies scoured the land around Halifax looking for Mi'kmaq.[5]

In July 1750, the Mi'kmaq killed and scalped 7 men who were at work in Dartmouth.[6] Four raids were against Halifax Peninsula. The first of these was in July 1750: in the woods on peninsular Halifax, the Mi'kmaq scalped Cornwallis' gardener, his son, and four others. They buried the son, left the gardener's body exposed, and carried off the other four bodies.[7]

In August 1750, 353 people arrived on the Alderney and began the town of Dartmouth. The town was laid out in the autumn of that year.[8] The following month, on September 30, 1750, Dartmouth was attacked again by the Mi'kmaq and five more residents were killed.[9]

In October 1750 a group of about eight men went out "to take their diversion; and as they were fowling, they were attacked by the Indians, who took the whole prisoners; scalped ... [one] with a large knife, which they wear for that purpose, and threw him into the sea ..."[10] The next year, on March 26, 1751, the Mi'kmaq attacked again, killing fifteen settlers and wounding seven, three of which would later die of their wounds. They took six captives, and the regulars who pursued the Mi'kmaq fell into an ambush in which they lost a sergeant killed.[11] Two days later, on March 28, 1751, Mi'kmaq abducted another three settlers.[11]

Dartmouth Massacre

The worst of these raids was the Dartmouth Massacre (1751). Three months after the previous raid, on May 13, 1751, Broussard led sixty Mi'kmaq and Acadians to attack Dartmouth again, in what would be known as the "Dartmouth Massacre".[12] Broussard and the others killed twenty settlers - mutilating men, women, children and babies - and took more prisoner.[13] A sergeant was also killed and his body mutilated. They destroyed the buildings. The British returned to Halifax with the scalp of one Mi'kmaq warrior, however, they reported that they killed six Mi'kmaq warriors.[14]

In 1751, there were two attacks on blockhouses surrounding Halifax. Mi'kmaq attacked the North Blockhouse (located at the north end of Joseph Howe Drive) and killed the men on guard. They also attacked near the South Blockhouse (located at the south end of Joseph Howe Drive), at a saw-mill on a stream flowing out of Chocolate Lake. They killed two men.[15] (Map of Halifax Blockhouses)

In 1753, when Lawrence became governor, the Mi'kmaq attacked again upon the sawmills near the South Blockhouse on the Northwest Arm, where they killed three British. The Mi'kmaq made three attempts to retrieve the bodies for their scalps.[16]

Prominent Halifax business person Michael Francklin was captured by a Mi'kmaw raiding party in 1754 and held captive for three months.[17]

French and Indian War

The town proved its worth as a military base in the French and Indian War (the North American Theatre of the Seven Years' War) as a counter to the French fortress Louisbourg in Cape Breton. Halifax provided the base for the Siege of Louisbourg (1758) and operated as a major naval base for the remainder of the war. On Georges Island (Nova Scotia) in the Halifax harbour, Acadians from the expulsion were imprisoned.

On 2 April 1756, Mi'kmaq received payment from the Governor of Quebec for 12 British scalps taken at Halifax.[18] Acadian Pierre Gautier, son of Joseph-Nicolas Gautier, led Mi’kmaq warriors from Louisbourg on three raids against Halifax in 1757. In each raid, Gautier took prisoners or scalps or both. The last raid happened in September and Gautier went with four Mi’kmaq and killed and scalped two British men at the foot of Citadel Hill. (Pierre went on to participate in the Battle of Restigouche.) [19]

By June 1757, the settlers at Lawrencetown had to be withdrawn completely from the settlement of Lawrencetown (established 1754) because the number of Indian raids eventually prevented settlers from leaving their houses.[20] In near-by Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, in the spring of 1759, there was another Mi'kmaq attack on Fort Clarence (located at the present day Dartmouth Refinery), in which five soldiers were killed.[21] In July 1759, Mi'kmaq and Acadians kill five British in Dartmouth, opposite McNabb's Island.[22]

After the French conquered St. John's, Newfoundland in June 1762, the success galvanized both the Acadians and Natives. They began gathering in large numbers at various points throughout the province and behaving in a confident and, according to the British,"insolent fashion". Officials were especially alarmed when Natives concentrated close to the two principal towns in the province, Halifax and Lunenburg, where there were also large groups of Acadians. The government organized an expulsion of 1300 people, shipping them to Boston. The government of Massachusetts refused the Acadians permission to land and sent them back to Halifax.[23]

The most famous event to take place at the Great Pontack (Halifax) was on May 24, 1758, when James Wolfe, who was headerquartered on Hollis Street, Halifax, threw a party at the Great Pontack prior to departing for the Siege of Louisbourg (1758). Wolfe and his men purchased 70 bottles of Madeira wine, 50 bottles of claret and 25 bottles of brandy.[24]Four days later, on May 29 the invasion fleet departed.[25] Wolfe returned to his headquarters in Halifax and the Great Pontack before his Battle of the Plains of Abraham. By the end of the year the Sambro Island Lighthouse was constructed at the harbour entrance to develop the port city's merchant and naval shipping.[26]

A permanent navy base, the Halifax Naval Yard was established in 1759. For much of this period in the early 18th century, Nova Scotia was considered a frontier posting for the British military, given the proximity to the border with French territory and potential for conflict; the local environment was also very inhospitable and many early settlers were ill-suited for the colony's wilderness on the shores of Halifax Harbour. The original settlers, who were often discharged soldiers and sailors, left the colony for established cities such as New York and Boston or the lush plantations of the Virginias and Carolinas. However, the new city did attract New England merchants exploiting the near-by fisheries and English merchants such as Joshua Maugher who profited greatly from both British military contracts and smuggling with the French at Louisbourg. The military threat to Nova Scotia was removed following British victory over France in the Seven Years' War.

With the addition of remaining territories of the colony of Acadia, the enlarged British colony of Nova Scotia was mostly depopulated, following the deportation of Acadian residents. In addition, Britain was unwilling to allow its residents to emigrate, this being at the dawn of their Industrial Revolution, thus Nova Scotia invited settlement by "foreign Protestants". The region, including its new capital of Halifax, saw a modest immigration boom comprising Germans, Dutch, New Englanders, residents of Martinique and many other areas. In addition to the surnames of many present-day residents of Halifax who are descended from these settlers, an enduring name in the city is the "Dutch Village Road", which led from the "Dutch Village", located in Fairview. Dutch here referring to the German "Deutsch" which sounded like "dutch" to Haligonian ears.

Lawrencetown was raided numerous times during the war and eventually had to be abandoned as a result (1756). For many decades Dartmouth remained largely rural, lacking direct transportation links to the growing military and commercial presence in Halifax, except for a dedicated ferry service. The former Halifax County was one of the five original counties of Nova Scotia created by an Order in Council in 1759.

Bury the Hatchet Ceremony

After agreeing to several peace treaties, the seventy-five year period of war ended with the Burial of the Hatchet Ceremony between the British and the Mi'kmaq. On June 25, 1761,[27] a “Burying of the Hatchet Ceremony” was held at Governor Jonathan Belcher’s garden on present-day Spring Garden, Halifax in front of the Court House. (In commemoration of these treaties, Nova Scotians annually celebrate Treaty Day on October 1.)

Halifax's fortunes waxed and waned with the military needs of the Empire. While it had quickly become the largest Royal Navy base on the Atlantic coast and had hosted large numbers of British army regulars, the complete destruction of Louisbourg in 1760 removed the threat of French attack. With peace in 1763, the garrison and naval squadron was dramatically reduced. With naval vessels no longer carrying the mail, Halifax merchants banded together in 1765 to build the Nova Scotia Packet a schooner to carry mail to Boston, later commissioned as the naval schooner HMS Halifax, the first warship built in English Canada.[28] Meanwhile Boston and New England turned their eyes west, to the French territory now available due to the defeat of Montcalm at the Plains of Abraham. By the mid-1770s the town was feeling its first of many peacetime slumps.

The American Revolution

The American Revolutionary War was not at first uppermost in the minds of most residents of Halifax. The government did not have enough money to pay for oil for the Sambro lighthouse. The militia was unable to maintain a guard, and was disbanded. Provisions were so scarce during the winter of 1775 that Quebec had to send flour to feed the town. While Halifax was remote from the troubles in the rest of the American colonies, martial law was declared in November 1775 to combat lawlessness.

On March 30, 1776, General William Howe arrived, having been driven from Boston by rebel forces. He brought with him 200 officers, 3000 men, and over 4,000 loyalist refugees, and demanded housing and provisions for all. This was merely the beginning of Halifax's role in the war. Throughout the conflict, and for a considerable time afterwards, thousands more refugees, often "in a destitute and helpless condition"[29] had arrived in Halifax or other ports in Nova Scotia. This would peak with the evacuation of New York, and continue until well after the formal conclusion of war in 1783. At the instigation of the newly arrived Loyalists who desired greater local control, Britain subdivided Nova Scotia in 1784 with the creation of the colonies of New Brunswick and Cape Breton Island; this had the effect of considerably diluting Halifax's presence over the region.

During the American Revolution, Halifax became the staging point of many attacks on rebel-controlled areas in the Thirteen Colonies, and was the city to which British forces from Boston and New York were sent after the over-running of those cities. After the War, tens of thousands of United Empire Loyalists from the American Colonies flooded Halifax, and many of their descendants still reside in the city today.

Dartmouth continued to develop slowly. In 1785, at the end of the American Revolution, a group of Quakers from Nantucket arrived in Dartmouth to set up a whaling trade. They built homes, a Quaker meeting house, a wharf for their vessels and a factory to produce spermaceti candles and other products made from whale oil and carcasses. It was a profitable venture and the Quakers employed many local residents, but within ten years, around 1795, the whalers moved their operation to Wales. Only one Quaker residence remains in Dartmouth and is believed to be the oldest structure in Dartmouth. Other families soon arrived in Dartmouth, among them was the Hartshorne family. They were Loyalists who arrived in 1785, and received a grant that included land bordering present-day Portland, King and Wentworth Streets. Woodlawn was once part of the land purchased by a Loyalist, named Ebenezer Allen who became a prominent Dartmouth businessman. In 1786, he donated land near his estate to be used as a cemetery. Many early settlers are interred in the Woodlawn cemetery including the remains of the "Babes in the Woods," two sisters who wandered into the forest and perished.

19th Century

In the peace after 1815, the city at first suffered an economic malaise for a few years, aggravated by the move of the Royal Naval yard to Bermuda in 1818. However the economy recovered in the next decade led by a very successful local merchant class. Powerful local entrepreneurs included steamship pioneer Samuel Cunard and the banker Enos Collins.

By the early 19th century, Dartmouth consisted of about twenty-five families. Within twenty years, there were sixty houses, a church, gristmill, shipyards, saw mill, two inns and a bakery located near the harbour.

Napoleonic Wars

Halifax was now the bastion of British strength on the East Coast of North America. Local merchants also took advantage of the exclusion of American trade to the British colonies in the Caribbean, beginning a long trade relationship with the West Indies. However, the most significant growth began with the beginning of what would become known as the Napoleonic Wars. Military spending and the opportunities of wartime shipping and trading stimulated growth led by local merchants such as Charles Ramage Prescott and Enos Collins. By 1796, Prince Edward, Duke of Kent, was sent to take command of Nova Scotia. Many of the city's forts were designed by him, and he left an indelible mark on the city in the form of many public buildings of Georgian architecture, and a dignified British feel to the city itself. It was during this time that Halifax truly became a city. Many landmarks and institutions were built during his tenure, from the Town Clock on Citadel Hill to St. George's Round Church, fortifications in the Halifax Defence Complex were built up, businesses established, and the population boomed.

War of 1812

Though the Duke left in 1800, the city's prosperity continued to grow throughout the Napoleonic Wars and War of 1812. While the Royal Navy squadron based in Halifax was small at the beginning of the Napoleonic Wars, it grew to a large size by the War of 1812 and ensured that Halifax was never attacked. The Naval Yard in Halifax expanded to become a major base for the Royal Navy and while its main task was supply and refit, it also built several smaller warships including the namesake HMS Halifax in 1806.[30]

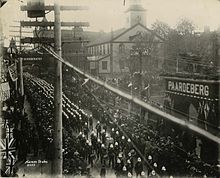

Capture of the USS Chesapeake

Several notable naval engagements occurred off the Halifax station. Most dramatic was the victory of the Halifax-based British frigate HMS Shannon which captured the American frigate USS Chesapeake and brought her to Halifax as prize. The Shannon, commanded by Halifax's own Provo Wallis, escorted her prize into Halifax, arriving there on 6 June. On the entry of the two frigates into the harbour, the naval ships already at anchor manned their yards, bands played martial music and each ship Shannon passed greeted her with cheers.[31] The 320 American survivors of the Battle of Boston Harbor were interned on Melville Island (Nova Scotia) in 1813, and their ship, renamed the HMS Chesapeake, was used to ferry prisoners from Melville to England's Dartmoor Prison.[32] Many officers were paroled to Halifax, but some began a riot at a performance of a patriotic song about the Chesapeake's defeat.[33] Parole restrictions were tightened: beginning in 1814, paroled officers were required to attend a monthly muster on Melville Island, and those who violated their parole were confined to the prison.[34]

As well, an invasion force which attacked Washington in 1813, and burned the Capitol and White House was sent from Halifax. The leader of the force was Robert Ross, who died in the battle and was buried in Halifax.

Early in the War, an expedition left Halifax under Lt Governor of Nova Scotia John Coape Sherbrooketo capture Maine. They named the new colony New Ireland, which the British held for the entirety of the war. The revenues which were taken from this invasion were used after the war to found Dalhousie University which is today Halifax's largest university. The city also thrived in the War of 1812 on the large numbers of captured American ships and cargoes captured by the British navy and provincial privateers.

The wartime boom peaked in 1814. Present day government landmarks such as Government House, built to house the governor, and Province House, built to house the House of Assembly, were both built during the city's peak of prosperity at the end of the War of 1812.

Saint Mary's University was founded in 1802, originally as an elementary school. Saint Mary's was upgraded to a college following the establishment of Dalhousie University in 1819; both were initially located in the downtown central business district before relocating to the then-outskirts of the city in the south end near the Northwest Arm. Separated by only few minutes walking distance, the two schools now enjoy a friendly rivalry.

During the 19th century Halifax became the birthplace of two of Canada's largest banks; local financial institutions included the Halifax Banking Company (located at Historic Properties (Halifax)), Union Bank of Halifax, People's Bank of Halifax, Bank of Nova Scotia, and the Merchants' Bank of Halifax, making the city one of the most important financial centres in colonial British North America and later Canada until the beginning of the 20th century. This position was somewhat rivalled by neighbouring Saint John, New Brunswick during the city's economic hey-day in the mid-19th century. Halifax was incorporated as the City of Halifax in 1842.

Having played a key role to maintain and expand British power in North America and elsewhere during the 18th century, Halifax played less dramatic roles in the many decades of peace during the 19th Century. However as one of the most important British overseas bases, the harbour's defences were successively refortified with the latest artillery defences throughout the century to provide a secure base for British Empire forces. Nova Scotians and Maritimers were recruited through Halifax for the Crimean War.

Crimean War

Citizens of HRM fought in the Crimean War. The Welsford-Parker Monument in Halifax is the oldest war monument in Canada (1860) and the only Crimean War monument in North America.[35] It commemorates the Siege of Sevastopol (1854–1855).

The city boomed during the American Civil War, mostly by supplying the wartime economy of the North but also by offering refuge and supplies to Confederate blockade runners. The port also saw Canada's first overseas military deployment as a nation to aid the British Empire during the Second Boer War.

Located at the mouth of the Sackville River, Bedford was originally known by several names, such as Fort Sackville, Ten Mile House, and Sunnyside. It used the name Bedford Basin (named after the Bedford Basin) from 1856 to 1902, when it was shortened to just Bedford, taking its name from the Duke of Bedford who was the Secretary of State in 1749.

In 1860, Starr Manufacturing Company was situated near the Shubenacadie Canal. The factory employed over 150 workers and manufactured ice skates, cut nails, vault doors, iron bridge work and other heavy iron products. The Mott's candy and soap factory, employing 100, opened at Hazelhurst (near present-day Hazelhurst and Newcastle Streets). Consumer Cordage, a rope factory on Wyse Road (which still stands, and barely survived the Halifax Explosion, and is now a pub), offered work to over 300, and the Symonds Foundry employed a further 50 to 100 people.

As the population grew, more houses were erected and new businesses established. Subdivisions such as Woodlawn, Woodside and Westphal developed on the outskirts of the town.

American Civil War

The American Civil War again saw much activity and prosperity in Halifax. Due to longstanding economic and social connections to New England as well as the Abolition movement, a majority of the population supported the North and many volunteered to fight in the Union army. However, parts of the city's merchant class, especially those trading in the West Indies, supported the South. A few merchants in the city made huge profits selling supplies and sometimes arms to both sides of the conflict (see for example Alexander Keith, Jr.). Confederate ships often called on the port to take on supplies, and make repairs. One such ship, the CSS Tallahassee, became a legend in Halifax when she made a daring midnight escape through from northern warships believed waiting at the harbour entrance. Halifax was also played a significant role in the Chesapeake Affair.

The Tallahassee Escape

During the American Civil War, on August 18, 1864, the Confederate ship CSS Tallahassee under the command of John Taylor Wood sailed into Halifax harbour for supplies, coal and to make repairs to her mainmast. Wood began loading coal at Woodside, on the Dartmouth shore. Two union ships were closing in on the Tallahassee, the Nansemont and the Huron. While Wood was offered an escort out of the harbour he instead slipped out of the harbour under the cover of night by going through the seldom used Eastern Passage between McNab’s Island and the Dartmouth Shore. The channel was narrow and crooked with a shallow tide so Wood hired the local pilot Jock Flemming. The Tallahasse left the Woodside wharf at 9:00 p.m. on the 19th. All the lights were out, but the residents on the Eastern Passage mainland could see the dark hull moving through the water, successfully evading capture.[36]

Confederation

After the American Civil War, the five colonies which made up British North America, Ontario, Quebec, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, held meetings to consider uniting into a single country. This was due to a threat of annexation and invasion from the United States. Canadian Confederation became a reality in 1867, but received much resistance from the merchant classes of Halifax, and from many prominent Halifax politicians due to the fact that both Halifax and Nova Scotia were at the time very wealthy, held trading ties with Boston and New York which would be damaged, and did not see the need for the Colony to give up its comparative independence. After confederation Halifax retained its British military garrison until British troops were replaced by the Canadian army in 1906. The British Royal Navy remained until 1910 when the newly created Royal Canadian Navy took over the Naval Dockyard.

The city's cultural roots deepened as its economy matured. The Victorian College of Art was founded in 1887 (later to become the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design.) Local artist John O'Brien excelled at portraits of the city's ships, yacht races and seascapes. The province's Public Archives and the provincial museum were founded in this period (first called the Mechanic's Institute, later the Nova Scotia Museum.)

After Confederation, boosters of Halifax expected federal help to make the city's natural harbor Canada's official winter port and a gateway for trade with Europe. Halifax's advantages included its location just off the Great Circle route made it the closest to Europe of any mainland North American port. But the new Intercolonial Railway (ICR) took an indirect, southerly route for military and political reasons, and the national government made little effort to promote Halifax as Canada's winter port. Ignoring appeals to nationalism and the ICR's own attempts to promote traffic to Halifax, most Canadian exporters sent their wares by train though Boston or Portland. No one was interested in financing the large-scale port facilities Halifax lacked. It took the First World War to at last boost Halifax's harbor into prominence on the North Atlantic.[37] Halifax business leaders attempted to diversity with manufacturing under Canada's National Policy creating factories such as the Acadia Sugar Refinery, the Nova Scotia Cotton Manufacturing Company, the Halifax Graving Dock and the Silliker Car Works. However this embrace with industrialization produced only modest results as most Halifax manufacturers found it hard to compete with larger firms in Ontario and Quebec.

In 1873 Dartmouth was incorporated as a town and a Town Hall was established in 1877. In 1883 "The Dartmouth Times" began publishing. In 1885 a railway station was built, and the first passenger service starts in 1886 with branch lines running to Windsor Junction by 1896 and the Eastern Shore by 1904. Two attempts were made to bridge The Narrows of Halifax Harbour with a railway line during the 1880s but were washed away by powerful storms. These attempts were abandoned after the line to Windsor Junction was completed. The line running through Dartmouth was envisioned to continue along the Eastern Shore to Canso or Guysborough, however developers built it inland along the Musquodoboit River at Musquodoboit Harbour and it ended in the Musquodoboit Valley farming settlement of Upper Musquodoboit, ending Dartmouth's vision of becoming a railway hub.

North-West Rebellion

Prior to Nova Scotia's involvement in the North-West Rebellion, Canada's "first war", the province remained hostile to Canada in the aftermath of the how the colony was forced into Canada. The celebration that followed the Halifax Provisional Battalion's return from the conflict by train across the county ignited a national patriotism in Nova Scotia. Prime Minister Robert Borden, stated that "up to this time Nova Scotia hardly regarded itself as included in the Canadian Confederation... The rebellion evoked a new sprit... The Riel Rebellion did more to unite Nova Scotia with the rest of Canada than any event that had occured since Confederation." Similarly, in 1907 Governor General Earl Grey declared, "This Battalion... went out Nova Scotians, they returned Canadians." The wrought iron gates at the Halifax Public Gardens were made in the Battalion's honour. [39]

20th Century

Second Boer War

During the Second Boer War (1899–1902), the First Contingent was composed of seven Companies from across Canada. The Nova Scotia Company (H) consisted of 125 men. (The total First Contingent was a total force of 1,019. Eventually over 8600 Canadians served.) The mobilization of the Contingent took place at Quebec. On October 30, 1899, the ship Sardinian sailed the troops for four weeks to Cape Town. The Boer War marked the first occasion in which large contingents of Nova Scotian troops served abroad (individual Nova Scotians had served in the Crimean War). The Battle of Paardeberg in February 1900 represented the second time Canadian soldiers saw battle abroad (the first being the Canadian involvement in the Nile Expedition).[40] Canadians also saw action at the Battle of Faber's Put on May 30, 1900.[41] On November 7, 1900, the Royal Canadian Dragoons engaged the Boers in the Battle of Leliefontein, where they saved British guns from capture during a retreat from the banks of the Komati River.[42] Approximately 267 Canadians died in the War. 89 men were killed in action, 135 died of disease, and the remainder died of accident or injury. 252 were wounded.

World War I

It was in World War I that Halifax would truly come into its own as a world class port and naval facility in the steamship era. The strategic location of the port with its protective waters of Bedford Basin sheltered convoys from German U-boat attack prior to heading into the open Atlantic Ocean. Halifax's railway connections with the Intercolonial Railway of Canada and its port facilities became vital to the British war effort during the First World War as Canada's industrial centres churned out material for the Western Front. In 1914, Halifax began playing a major role in the First World War, both as the departure point for Canadian Soldiers heading overseas, and as an assembly point for all convoys (a responsibility which would be placed on the city again during WW2). Most Canadian troops left overseas from Halifax aboard enormous peacetime ocean liners converted to troopships such as RMS Olympic and RMS Mauretania as well as hundreds of other smaller liners. The city also served as the return point for a steady stream of wounded soldiers returning on hospital ships. A new generation of gun batteries, searchlights and an anti-submarine net defended the harbour, manned by a large garrison of soldiers. Halifax's limited 19th Century housing and transit facilities were heavily burdened. In November 1917, a subway system plan was presented to City Hall, but the city did not pursue the scheme.

Halifax Explosion

The war was seen as a blessing for the city's economy, but in 1917 a French munitions ship, the Mont Blanc, collided with a Norwegian ship, the Imo. The collision sparked a fire on the munitions ship which was filled with 2,300 tons of wet and dry picric acid (used for making lyddite for artillery shells), 200 tons of trinitrotoluene (TNT), 10 tons of gun cotton, with drums of Benzol (High Octane fuel) stacked on her deck. On December 6, 1917, at 9:04:35 AM[43] the munitions ship exploded in what was the largest man-made explosion before the first testing of an atomic bomb, and is still one of the largest non-nuclear man-made explosions. Items from the exploding ship landed five kilometres away. The Halifax Explosion decimated the city's north end, killing roughly 2,000 inhabitants, injuring 9,000, and leaving tens of thousands homeless and without shelter.

The following day a blizzard hit the city, hindering recovery efforts. Immediate help rushed in from the rest of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland. In the following week more relief from other parts of North America arrived and donations were sent from around the world. The most celebrated effort came from the Boston Red Cross and the Massachusetts Public Safety Committee; as an enduring thank-you, since 1971 the province of Nova Scotia has donated the annual Christmas tree lit at the Boston Common in Boston.[44][45]

The explosion and the rebuilding which followed had important impacts on the city: reshaping the layout of North End neighbourhoods; creating a progressive housing development known as the Hydrostone; and hastening the move of railways to the South End of the City.

Between the Wars

The city's economy slumped after the war, although reconstruction from the Halifax Explosion brought new housing and infrastructure as well as the establishment of the Halifax Shipyard. However, a tremendous drop in worldwide shipping following the war as well as the failure of regional industries in the 1920s brought hard-times to the city, further aggravated by the Great Depression in 1929. One bright spot was the completion of Ocean Terminals in the city's south end, a large modern complex to trans-ship freight and passengers from steamships to railways. The harbour's strategic location made the city the base for the famous and successful salvage tug Foundation Franklin which brought lucrative salvage jobs to the city in the 1930s. While a military airport had been in operation at Dartmouth's Shearwater base since WW I, the city opened its first civilian airport in the city's West End at Chebucto Field in 1931. Pan-Am began international flights from Boston in 1932.[46]

War Plan Red, a military strategy developed by the United States Army during the mid-1920s and officially withdrawn in 1939, involved an occupation of Halifax by US forces following a poison gas first strike, to deny the British a major naval base and cut links between Britain and Canada.

World War II

Halifax played an even bigger role in the Allied naval war effort of World War II. The only theatre of War to be commanded by a Canadian was the North Western Atlantic, commanded from Halifax by Rear-Admiral Leonard W. Murray. Halifax became a lifeline for preserving Britain during the Nazi onslaught of the Battle of Britain and the Battle of the Atlantic, the supplies helping to offset a threatened amphibious invasion by Germany. Many convoys assembled in Bedford Basin to deliver supplies to troops in Europe. The city's railway links fed large numbers of troopships building up Allied armies in Europe. The harbour became an essential base for Canadian, British and other Allied warships. Very much a front-line city, civilians lived with the fears of possible German raids or another accidental ammunition explosion. Well-defended, the city was never attacked although some merchant ships and two small naval vessels were sunk at the outer approaches to the harbour. However, the sounds and sometimes the flames of these distant attacks fed wartime rumours, some of which linger to the present day of imaginary tales of German U-Boats entering Halifax Harbour. The city's housing, retail and public transit infrastructure, small and neglected after 20 years of prewar economic stagnation was severely stressed. Severe housing and recreational problems simmered all through the war and culminated in the Halifax Riot on VE Day in May 1945. The war was also marked by a massive explosion of the Navy's Bedford ammunition magazine which accidentally blew up on July 18, 1945 causing the evacuation of the north end of Halifax and Dartmouth and fears of another Halifax Explosion

Bedford Magazine Explosion

During World War II Dartmouth as with Halifax was busy supporting Canada's war effort in Europe. On July 18, 1945, at the end of the Second World War, a fire broke out at the magazine jetty on the Bedford Basin, north of Dartmouth. The fire began on a sunken barge and quickly spread to the dock. A violent series of large explosions ensued as stored ammunition exploded. The barge responsible for starting the explosion presently lies on the seabed near the eastern shoreline adjacent to the Magazine Dock.[1] [2]

Halifax Riot

The Halifax Riot happened on VE-Day, 7–8 May 1945 in Halifax and Dartmouth, Nova Scotia began as a celebration of the World War II Victory in Europe. This rapidly declined into a rampage by several thousand servicemen, merchant seamen and civilians, who looted the City of Halifax. Although a subsequent Royal Commission chaired by Justice Roy Kellock blamed lax naval authority and specifically Rear-Admiral Leonard W. Murray, it is generally accepted that the underlying causes were a combination of bureaucratic confusion, insufficient policing and antipathy between the military and civilians, fueled by the presence of 25,000 servicemen who had strained Halifax wartime resources to the limit.

Mid-century transportation and urban renewal

An important port for the Caribbean-Canada-United Kingdom shipping triangle during the 19th century, Halifax's strategic harbour was also an integral part of Allied war efforts during both world wars.

After World War Two, Halifax did not experience the postwar economic malaise it had so often experienced after previous wars. This was partially due to the Cold War which required continued spending on a modern Canadian Navy. However, the city also benefited from a more diverse economy and postwar growth in government services and education. The 1960s-1990s saw less suburban sprawl than in many comparable Canadian cities in the areas surrounding Halifax. This was partly as a result of local geographies and topography (Halifax is extremely hilly with exposed granite not conducive to construction), a weaker regional and local economy, and a smaller population base than, for example, central Canada or New England. There were also deliberate local government policies to limit not only suburban growth but also put some controls on growth in the central business district to address concerns from heritage advocates.

Urban renewal plans in the 1960s and 70s resulted in the loss of much of its heritage architecture and community fabric in large downtown developments such as the Scotia Square mall and office towers. However, a citizens protest movement limited further destructive plans such as a waterfront freeway which opened the way for a popular and successful revitalized waterfront. Selective height limits were also achieved to protect the views from Citadel Hill. However, municipal heritage protection remained weak with only pockets of heritage buildings surviving in the downtown and constant pressure from developers for further demolition. Selective height restrictions were adopted to protect views from Citadel Hill which triggered battles over proposed developments that would fill vacant lots or add height to existing historical structures.

Another casualty during the 1960s and 1970s period of expansion and urban renewal was the Black community of Africville which was declared a slum, demolished and its residents displaced to clear land for industrial use as well as for the A. Murray MacKay Bridge. The repercussions continue to this day and a 2001 United Nations report has called for reparations be paid to the community's former residents.

In 1980, Bedford incorporated as a separate municipality (a town).

Restrictions on development were relaxed somewhat during the 1990s, resulting in some suburban sprawl off the peninsula. Today the community of Halifax is more compact than most Canadian urban areas although expanses of suburban growth have occurred in neighbouring Dartmouth, Bedford and Sackville. One development in the late 1990s was the Bayers Lake Business Park, where warehouse style retailers were permitted to build in a suburban industrial park west of Rockingham. This has become an important yet controversial centre of commerce for the city and the province as it used public infrastructure to subsidise multi-national retail chains and draw business from local downtown business. Much of this subsidy was due to competition between Halifax, Bedford and Dartmouth to host these giant retail chains and this controversy helped lead the province to force amalgamation as a way to end wasteful municipal rivalries. In the past few years, urban housing sprawl has even reached these industrial/retail parks as new blasting techniques permitted construction on the granite wilderness around the city. What was once a business park surrounded by forest and a highway on one side has become a large suburb with numerous new apartment buildings and condominiums. Some of this growth has been spurred by offshore oil and natural gas economic activity but much has been due to a population shift from rural Nova Scotian communities to the Halifax urban area. The new amalgamated city has attempted to manage this growth with a new master development plan.

21st Century

During the mid-to-late 1990s HRM developed a strong national and international following to its music scene, particularly the alternative genre. Musical acts from HRM include such notable groups as: Sloan, The Nellis Complex, Thrush Hermit, Christina Clark and Sarah McLachlan.

Although discussions had been underway for decades in the former cities of Halifax and Dartmouth, a deal was finally signed in 2003 that saw the construction of several sewage treatment plants for the core urban area, as well as an extensive trunk collector system to link outfalls to each plant. For the first time since settlement came to the area, human sewage will be treated before it is discharged into the Atlantic Ocean; estimated start-up is for 2007.

Hurricane Juan

On September 29, 2003, HRM was hit by Hurricane Juan which made landfall west of the urban core. Juan was the most powerful hurricane to directly hit the Halifax-Dartmouth metropolitan area since 1893. The storm caused a serious disruption throughout the central and eastern part of the municipality during the first week of October. Although some areas of the urban core only lost electricity for a brief period, outlying rural regions in the eastern part of HRM were without electricity for up to two weeks. Millions of trees in HRM were damaged or destroyed in the dense forests along the Eastern Shore.

On January 13, 2008 the government of Nova Scotia proclaimed the "The Halifax Regional Municipality Charter Act" giving the municipality more powers to address the specific needs of HRM.[3]

Amalgamation

The Amalgamation of Halifax, Nova Scotia was the creation of the current political borders of Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada after amalgamating, annexing, and merging with surrounding municipalities. The most recent occurrence of amalgamation was in 1996, which resulted in Halifax's current boundaries.

See also

- List of mayors of Halifax, Nova Scotia

- List of people from the Halifax Regional Municipality

- History of Dartmouth

- Halifax (former city)

- Military history of Nova Scotia

- Halifax Regional Municipality

References

- ^ Grenier, John. The Far Reaches of Empire. War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. Norman: U of Oklahoma P, 2008; Thomas Beamish Akins. History of Halifax, Brookhouse Press. 1895. (2002 edition). p 7

- ^ Wicken, p. 181; Griffith, p. 390; Also see http://www.northeastarch.com/vieux_logis.html

- ^ Harry Chapman. In the Wake of the Alderney: Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, 1750-2000. Dartmouth Historical Association. 2000. p. 23; John Grenier (2008). The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. p.150; For the primary sources that document the Raids on Dartmouth see the Diary of John Salusbury (diarist): Expeditions of Honour: The Journal of John Salusbury in Halifax; also see A genuine narrative of the transactions in Nova Scotia since the settlement, June 1749, till August the 5th, 1751 [microform] : in which the nature, soil, and produce of the country are related, with the particular attempts of the Indians to disturb the colony / by John Wilson. Also see http://www.blupete.com/Hist/NovaScotiaBk1/Part5/Ch07.htm

- ^ Thomas Beamish Akins. History of Halifax, Brookhouse Press. 1895. (2002 edition). p 18

- ^ Thomas Beamish Akins. History of Halifax, Brookhouse Press. 1895. (2002 edition). p 19

- ^ Thomas Atkins. History of Halifax City. Brook House Press. 2002 (reprinted 1895 edition). p 334

- ^ Thomas Atkins. History of Halifax City. Brook House Press. 2002 (reprinted 1895 edition). p 334

- ^ Akins, p. 27

- ^ John Grenier (2008). The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. p.159;

- ^ John Wilson A Genuine Narrative of the Transactions in Nova Scotia since the Settlement, June 1749 till August the 5th 1751. London: A. Henderson, 1751 as recorded by Archibald MacMechan in Red Snow on Grand Prepp. 173-174

- ^ a b John Grenier (2008). The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. p.160

- ^ Atkins, p. 27-28

- ^ John Grenier (2008). The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. p.160; Cornwallis' official report mentioned that four settlers were killed and six soldiers taken prisoner. See Governor Cornwallis to Board of Trade, letter, June 24, 1751, referenced in Harry Chapman, p. 29; John Wilson reported that fifteen people were killed immediately, seven were wounded, three of whom would die in hospital; six were carried away and never seen again" (See A genuine narrative of the transactions in Nova Scotia since the settlement, June 1749, till August the 5th, 1751 [microform] : in which the nature, soil, and produce of the country are related, with the particular attempts of the Indians to disturb the colony / by John Wilson

- ^ See annonmous private letter printed by Harry Chapman, p. 30.

- ^ Piers, Harry. The Evolution of the Halifax Fortress (Halifax, PANS, Pub. #7, 1947), p. 6 As cited in Peter Landry's. The Lion and the Lily. Vol. 1. Trafford Press. 2007. p. 370

- ^ Thomas Atkins. History of Halifax City. Brook House Press. 2002 (reprinted 1895 edition). p 209

- ^ "L.R. Fisher, ''Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online''". Biographi.ca. 2007-10-18. Retrieved 2012-08-27.

- ^ J.S. McLennan. Louisbourg: From its foundation to its fall (1713-1758). 1918, p. 190

- ^ Earle Lockerby. Pre-Deportation Letters from Ile Saint Jean. Les Cahiers. La Societe hitorique acadienne. Vol. 42, No2. June 2011. pp. 99-100

- ^ Bell Foreign Protestants. p. 508

- ^ Harry Chapman, p. 32; Faragher 2005, p. 410

- ^ Beamish Murdoch. History of Nova Scotia. Vol.2. p. 366

- ^ Patterson, 1994, p. 153; Brenda Dunn, p. 207

- ^ Major, p.181

- ^ Johnston. Endgame

- ^ Raddall, Thomas Halifax: Warden of the North, (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart) p. 64

- ^ Some accounts give the date as 8 July 1761

- ^ Trevor Kenchington, "The Navy's First Halifax", Argonauta, Canadian Nautical Research Society, Vol. X, No. 2 (April 1993), p. 9

- ^ Akins, Dr. Thomas B. History of Halifax City, p. 85.

- ^ Julian Gwyn, Ashore and Afloat: The British Navy and the Halifax Naval Yard Before 1820, University of Ottawa Press (2004) ISBN 9780776605739

- ^ Padfield 1968, p. 188

- ^ Shea & Watts 2005, pp. 27–29.

- ^ Shea & Watts 2005, p. 30.

- ^ Shea & Watts 2005, p. 31.

- ^ James Cornall (November 10, 1998). Halifax:: South End. Arcadia Publishing. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-7385-7272-7.

- ^ Greg Marquis. In Armagedon's Shadow: The Civil War and Canada's Maritime Provinces, (1998) McGill Queens Press, p. 233

- ^ James D. Frost, "Halifax: the Wharf of the Dominion, 1867-1914." Journal of the Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society 2005 8: 35-48.

- ^ David A. Sutherland. "Halifax Encounter with the the North-West Uprising of 1885. Journal of the Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society. Vol. 13, 2010. p. 74

- ^ David A. Sutherland. "Halifax Encounter with the the North-West Uprising of 1885". Journal of the Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society. Vol. 13, 2010. p. 73

- ^ Canadian War Museum (2008). "Battle of Paardeberg". Canadian War Museum. Retrieved 2008-05-10. [dead link]

- ^ Canadian War Museum (2008). "Battle of Faber's Put". Canadian War Museum. Retrieved 2008-05-10. [dead link]

- ^ Canadian War Museum (2008). "Battle of Leliefontein". Canadian War Museum. Retrieved 2008-05-10. [dead link]

- ^ "CBC - Halifax Explosion - Disputes over Time". Cbc.ca. Retrieved 2012-08-27.

- ^ "Boston Common Holiday Tree Lighting Coming December 3", Press Release, Parks Department, City of Boston, November 13, 2009

- ^ "Holiday Tree Lightings Begin November 23", Press Release, Parks Department, City of Boston, November 09, 2009

- ^ ""History of the Halifax International Airport", ''Halifax International Airport Authority" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-08-27.